Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

by local landlords, entrepreneurs and craftsmen. Tighter linkages with London

took place during assize week, when judges appeared on regular circuit, but then

they quickly moved on. By the s, not only had regional capitals almost

tripled in number, but they had acquired a host of new institutions. They housed

stock exchanges and branches of the Bank of England, regional post offices,

public universities and departments of the national bureaucracy.

24

Thousands of

Lynn Hollen Lees

24

A. E. Smailes, ‘The urban hierarchy in England and Wales’, Geography, no. , , (),

–.

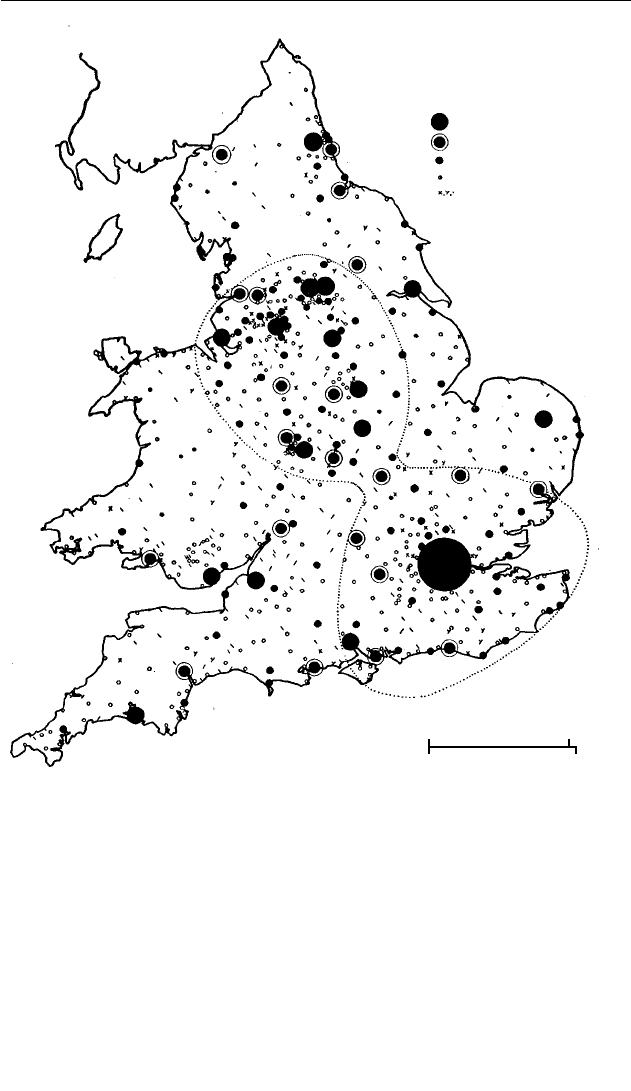

Map . The urban hierarchy of England and Wales in

Source: Arthur E. Smailes, ‘The urban hierarchy in England and Wales’,

Geography, ().

0 50 miles

0 80 km

Major cities

Cities

Minor cities Major towns

Towns

Sub-towns

‘Hour glass’indicates area of maximum

urban concentration

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

their residents lived in municipal housing, used town-supplied water, electricity

and trams. They shopped in chain stores, used branch banks and bought standar-

dised goods using state-issued ration coupons. Decisions about production, sale

and raw material sources were made outside the region, and investments

responded to international opportunities and constraints. Greater centrality went

along with larger size and complexity. State and economy operated symbiotically

to knit together the localised networks of the early industrial period. Moreover,

increased public investment could compensate for the retreat of private capital

and economic decline.

(iii) :

To see an urban network in operation, let us follow interconnections from vil-

lages to a county town in the nineteenth century. Leicestershire has a particu-

larly clear-cut central-place system. A ring of market towns – Hinckley, Market

Harborough and Melton Mowbray, to name only a few – surround the county

capital at a distance of about miles ( km), and each of the market towns has

a penumbra of villages linked to it by road. In the early nineteenth century, both

the county’s agriculture and its framework knitting industry depended upon

these urban markets, which were linked to the villages by extensive carrier ser-

vices. In about and in around village men made weekly trips

with a horse and cart into Leicester or one of the country’s market towns. They

moved along fixed routes, bringing produce in to retailers for sale, delivering

packages, carrying passengers, making small purchases and returning home by

evening. When they got to town, they crowded into local inns to drink and to

trade news, bringing information back home along with yarn, medicine and

crockery. Before the appearance of rural omnibus services – in Leicestershire in

the s – they provided the only public transport. Where rural industries

flourished, the carriers collected raw materials from urban warehouses, delivered

them to the artisans and then took back the finished goods. Alan Everitt esti-

mates that in England and Wales around , about , such carriers moved

among villages and market towns, providing necessary transportation and mar-

keting services. In fact, such services increased in frequency during the nine-

teenth century and were supplemented by scores of light rail lines, which

intensified intraregional flows of goods and people.

25

Although trains linked

cities and the larger towns by , the transportation and marketing needs of

the rural and small-town population, which expanded during the early phases

of industrial urbanisation, were not satisfied by the largely intercity routes of the

railway.

By the s, in the rapidly industrialising areas, complex transportation ser-

vices aided the local movements of people and goods. In the Glasgow region

Urban networks

25

A. Everitt, Landscape and Community in England (London, ), pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

around , several omnibus and hackney carriage companies linked local

towns and suburbs in to the centre. Mail coaches linked Glasgow to about two

dozen other more distant Scottish cities, while steamboats left the port regularly

for places as far north as Stornoway and west to Ireland. In addition, the Paisley,

Monkland, Forth & Clyde canals carried thousands of passengers regularly

around the district. In fact, by the s, the early railroad lines had teamed up

with coaches and steamers to provide integrated transit services in the region.

26

Urbanisation in Lowland Scotland during the nineteenth century stemmed

largely from industrial development: the textile towns of Dunfermline, Hawick,

Kilmarnock and Paisley and the coal and iron processing towns of Falkirk,

Hamilton, Coatbridge and Motherwell grew faster than older marketing towns.

Railway links eased the export of goods and imports of people. Edinburgh sup-

plied higher level financial, educational, medical and religious services, while

Glasgow acted as the key city for industry and trade, while developing both

middle-class suburbs and industrial satellites like Springburn, which grew around

its railway and engineering works.

27

Capital investments flowed into urban infra-

structures, as well as into firms.

Elaborate transit systems were needed because of the multiple functions of

county capitals, as well as regional geographies of production and distribution.

To return to a Midland example, Thomas Cook’s Guide to Leicester for

pointed out the city’s theatre, library, Shakespearean rooms, assembly rooms,

New Hall for concerts and public meetings, post office, union workhouse and

lunatic asylum. Moreover, the town boasted five banks, eleven schools, eight

Anglican parishes, an archdeacon’s office, twenty-four dissenting chapels, an

excise office, two gaols, four hospitals and a general dispensary that served the

poor of the county as well as the town.

28

A host of public institutions, charities,

clubs and companies were headquartered in the city. People came to town for

race meetings or to see exhibitions from the Leicestershire Floral Society. Others

attended elections, assizes or demonstrations. They went to the parks to hear

evangelists, to the Temperance hall for testimonal soirées or oratorios.

29

For

gentry and freeholders, stocking weavers and Chartists, the county town focused

political, judicial and cultural concerns. Leicester anchored a ‘craft-region’ as

well as a county community, and the town helped to promote a regional iden-

tity through its many institutions and activities.

30

Lynn Hollen Lees

26

J. R. Hume, ‘Transport and towns in Victorian Scotland’, in G. Gordon and B. Dicks, eds.,

Scotttish Urban History (Aberdeen, ), pp. –.

27

D. Turnock, The Historical Geography of Scotland since (Cambridge, ); J. Doherty, ‘Urban-

ization, capital accumulation, and class struggle in Scotland, –’, in G. W. Whittington

and I. D. Whyte, An Historical Geography of Scotland (London, ), pp. –.

28

T. Cook, Guide to Leicester, Containing the Directory and Almanac for (Leicester, ).

29

The active social and cultural life of the region is chronicled in the Leicestershire Mercury.

30

A. Everitt, ‘Country, county and town: patterns of regional evolution in England’, TRHS, th

series, (), , .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Of course, much smaller towns than Leicester could boast flourishing public

cultures and industrial establishments, fed by the rising incomes and new demands

of consumers in their hinterlands. Even relatively remote, weakly urbanised

counties had quite sophisticated central places. The Cumbrian market town of

Ulverston, which had , residents and was the fourth largest town in the

county by , served as the central place for a proto-industrial area from the

lower Furness Fells to the south-west Cumbrian Dales. Its markets, inns and

taverns catered to a large commercial traffic. But the town also had boarding

schools for young ladies, hairdressers, confectioners, printers and tea dealers. The

town’s book club and theatre drew professional people and gentry, while artisans

used its friendly societies, savings banks and dissenting chapels. According to

J. D. Marshall, Cumbrian market towns expanded markedly along with rural

industry in the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The coming of

the railway around benefited the larger centres by drawing business away

from the smaller ones. Although Ulverston maintained its centrality as late as

, nearby places such as Bottle and Broughton lost population as did the rural

areas.

31

Then during the second half of the nineteenth century, Cumbrian

regional networks adjusted to the rapid industrialisation of coastal coal and iron

districts. Barrow and Workington turned into boom towns as people left agricul-

tural labour markets for urban ones. By , per cent of the Cumbrian pop-

ulation lived in the coastal strip and its major towns. Rural de-industrialisation

and the decline of the local cotton industry undermined the active urban network

of the proto-industrial period but produced alternative sets of settlements.

32

The

capital investments of the industrial period reworked the spatial organisation of

the area, and labour migration followed.

Particularly in industrialising regions, complex geographies of production,

merchanting and finance arose on the basis of local social structures and regional

ties. Capitalist investment strategies developed in tandem with custom and com-

munity. Wool was imported into the major towns of the West Riding, but then

shifted by cart to a variety of sites to be processed and reprocessed. Dozens of

mechanised carding, scribbling and fulling mills lay along the Calder and Aire

rivers, while thousands of clothiers and journeymen wove cloth in small work-

shops or their homes in the villages and small towns throughout the district. Sales

took place in the cloth halls of Leeds, Bradford, Halifax, Huddersfield and

Wa ke field primarily, each of which served a large, but fluctuating number of

producers who brought the finished goods in to the central place. By the mid-

s, production had become much more concentrated along the Aire near

Leeds, along the Calder around and west of Wakefield, in Huddersfield and

Urban networks

31

J. D. Marshall, ‘The rise and transformation of the Cumbrian market town, –’, NHist.,

(), –.

32

J. D. Marshall, ‘Stages of industrialization in Cumbria’, in P. Hudson, ed., Regions and Industries

(Cambridge, ), pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Halifax, and integrated firms handling multiple branches of production grew.

33

Yet the area was not a homogeneous whole: the division between worsted and

woollen production rested on different agricultural environments, methods of

finance and entrepreneurial control. In the West Riding around Halifax and

Bradford, worsted production first developed in upland pastoral areas where

early enclosure and a declining manorial system had produced a landless rural

proletariat and a small group of putting-out capitalists. The transition to factory

production in urban sites took place fairly rapidly after the s with finance

supplied by the large putting-out merchants and factory masters from the cotton

trade. In contrast, woollen production in the territory around Huddersfield,

Dewsbury and Leeds developed amidst more fertile land and a more vital mano-

rial system. The holders of manors and large estates fostered a system of mixed

farming and cloth production. In that area, independent weaving households

survived and marketed their produce in the large town cloth halls. Jointly

financed fulling and carding mills provided local clothiers the services they

needed to survive, and local landowners helped to provide capital for mills and

workshops.

34

In the longer run, differential access to credit reshaped the geography of pro-

duction and trade in both the woollen and worsted districts. After , the

growth of banks created a regional capital market, linked to London via the

Leeds branch of the Bank of England. The largest firms, whose owners served

as bank directors, had easier access to credit and information.

35

Financial services

and excellent transportation were part of the comparative advantage of the larger

towns. Leeds, for example, was linked by canal to Liverpool in and by

railway to Hull by . Entrepreneurs could get cheap coal from local mines,

and raw materials, such as flax from the Baltic region, came via Hull, then by

canal and railway. Early investments in steam engines and spinning mills made

the city a technological leader. As early as , local engineering firms had

begun to supply the steam engines, hackles, gills and combs needed in the textile

industry.

36

Its expansion in the area fostered a wave of allied investment in Leeds

and other West Riding towns. In the longer run, of course, flax manufacturing

virtually disappeared, leaving dozens of empty mills in the town, and woollen

manufacture shifted from central areas to outlying townships. But the region’s

Lynn Hollen Lees

33

D. Gregory, Regional Transformation and Industrial Revolution (London, ), pp. , , .

34

P. Hudson, ‘From manor to mill: the West Riding in transition’, in M. Berg, P. Hudson and M.

Sonenscher, eds., Manufacture in Town and Country before the Factory (Cambridge, ), pp. –.

35

P. Hudson, The Genesis of Industrial Capital (Cambridge, ); P. Hudson, ‘Capital and credit in

the West Riding wool textile industry c. –’, in Hudson, ed., Regions and Industries, pp.

–. For a discussion of regional organisation in the West Riding in the mid-twentieth century,

see R. E. Dickinson, City and Region (London, ), pp. –.

36

E. J. Connell and M. Ward, ‘Industrial development, –’, in D. Fraser, ed., A History of

Modern Leeds (Manchester, ), pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

capital was mobile and by had shifted into clothing, footwear, chemicals

and heavy engineering. Networks of supply and marketing had to be reworked,

but that was easily done. The next phase of disinvestment and reinvestment took

place in the interwar period, when local manufacturing declined precipitously.

As old woollen firms disappeared, banks and retail stores enlarged. Commerce,

administration and the professions became the city’s business, rather than

woollen production.

37

The question of why some businessmen manage to react

successfully to economic changes and others fail to do so is ultimately unanswer-

able on a general level. But settings matter. The ability of Leeds entrepreneurs

to adapt was facilitated by transportation networks, by the size of the city’s con-

sumer market and by a wealth of local institutions that provided capital, techni-

cal expertise and commercial information.

Industrial capitalism made even greater changes over the longer run in the

urban networks of the mining areas. In a mineral-based energy economy, trans-

portation costs decline because production is punctiform, rather than areal. At

limited cost, canals and railroads linked pitheads with the nearby industrial areas

and towns. Regional marketing networks, centred on major ports and industrial

towns, solidified, and virtually unlimited, cheap energy supplies enabled entre-

preneurs to break through earlier ceilings to growth.

38

Interlocking and inter-

acting firms employed the labour and capital that helped to accelerate

urbanisation in the industrial regions.

South Wales provides a particularly dramatic example of change. In ,

South Wales was still primarily an agricultural area dependent upon Bristol for

its manufactured goods and marketing services. The Welsh population relied on

eleven rather small towns, which acted primarily as service centres. Their

bankers, professionals and artisans served interior hinterlands, linked by carriers

and a few major roads. Although the presence of theatres, race tracks and poor

law unions signalled cultural and administrative importance, they were largely

untouched by industrial urbanisation. But coal and iron had already begun to

transform South Wales into an industrialised region organised around Merthyr

Ty d fil and Cardiff. Isolated valleys quickly acquired villages and then towns as

the early iron masters and mine owners built housing near their blast furnaces

and pitheads. Mining settlements, such as Bargoed and Tonypandy, multiplied

after . The Glamorganshire canal after and the Taff Vale Railway after

brought the rich harvest from the Aberdare and Rhondda valleys out to

the coast.

39

Cardiff, one of the major beneficiaries, grew from , in to

Urban networks

37

Michael Meadowcroft, ‘The years of political transition, –’, in Fraser, ed., Leeds, pp.

–.

38

Wrigley, People, Cities and Wealth, pp. –; see also D. Gregory, ‘Three geographies of industri-

alization’, in Dodgshon and Butlin, eds., Historical Geography, pp. –.

39

Carter, The Towns of Wales; M. J. Daunton, Coal Metropolis (Leicester, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

, in , becoming the region’s capital. As more elaborate transport

systems eased migration, Swansea and Newport grew into major cities; resorts

such as Barry Island and Porthcawl developed, and industrial villages became

industrial towns. But Wales paid a price for the heavy dependence of local urban

networks upon coal mining. Merthyr declined in importance when the supply

of local iron ore became exhausted and the cost of importing it was too high.

By , the region turned to the export of coal through Cardiff, but no

significant manufacturing or shipbuilding industries ever developed in the

regional capital. By late in the century, the city’s port needed expansion and

modernisation, which was not forthcoming. The major shippers and merchants

came from outside the region, and the Bute family by that point had retreated

from aggressive municipal leadership. Coal and shipowners built a rival dock and

railway at Barry, which siphoned off much trade and left Cardiff with an obso-

lete, underutilised port. The final blow to the city’s major industry came after

with the collapse of coal exporting, as steamships shifted to oil and inter-

nal combustion engines, and the British coal industry failed to overcome increas-

ing difficulties of extraction with greater investment and productivity. As local

companies went into liquidation, Cardiff turned from ‘coal metropolis’ to an

administrative and retail centre.

40

The pattern of industrial expansion that dominated Britain during the indus-

trial era was a regional one: firms concentrated all the stages of production of a

commodity within one area, mixing management, production and exporting.

Regional divisions of labour arose, therefore, from an industrial base – spinners

and weavers in Lancashire and the West Riding, miners in the North-East and

South Wales, engineers in the West Midlands and the South-East. Regional

differentiation increased not only with sectoral collapse but also with national-

isation, which accelerated changes in internal class structure. Upper-level man-

agement shifted to the London region; research and development groups could

be centralised.

41

The urban networks created in the era of industrial urbanisation were effective

and flexible, but inherently unstable. Many entrepreneurs reacted to technolog-

ical change and calculations of profitability, shifting money and investment when

opportunity beckoned. Roads of entry could easily become roadways of exit for

businessmen as well as for their products. Locations had to remain advantageous

in either industrial or commercial terms for them to remain attractive to inves-

tors. In the longer run, the landscape of industrial urbanism in the north of

Britain was reshaped by the transference of much capital investment southward

and overseas. After export markets for northern goods collapsed, the lure of

potentially higher profits in new industries located elsewhere was difficult to

resist.

Lynn Hollen Lees

40

Daunton, Coal Metropolis, pp. –.

41

Massey, Spatial Divisions, pp. , –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

(iv)

Before the Industrial Revolution, Britain had many towns, but only one city.

William Cobbett branded it the ‘Great Wen’, for its density, dominance and

draining of national, and indeed international, resources. The largest city in the

world by the s, London reached out to India and the Caribbean through its

port, to Europe and Latin America through its bankers, to Ireland and Scotland

through its parliament, and through the length and breadth of Britain via its

newspapers and insatiable demand for workers and consumer goods. London was

and remains a primate city, whose size is sustained by its position in economic,

cultural and political hierarchies. Yet the growth of the industrial economy and

a more centralised state shifted the nature of links within Britain between

metropolis and periphery. Not only did London’s degree of demographic

primacy shrink, but the capital’s relative political and economic influence dimin-

ished in comparison to that of the new industrial cities of the Midlands and the

North during most of the nineteenth century. If London’s size is compared to

that of the second largest British town, it moved from being more than times

as large in to multipliers of in , in , and . in . Although

London’s share of the total British population rose slightly during the nineteenth

century, by more people lived in the textile counties of Lancashire and the

West Riding than in the capital. Urbanised regions overtook the metropolis

quite early in terms of population, fixed investments in plant and steam power,

and in manufacturing for export. In addition, the congruence between relative

size and economic or cultural influence that seemed so clear in the seventeenth

and eighteenth centuries broke down. In the heyday of industrial urbanisation,

British networks of cultural, political and economic exchange were more foot-

loose than they had been in the early modern period and the dominance of

London was less secure. Regional novels, newspapers, choruses and brass bands

had devoted audiences. Culture could be created locally.

The case for a diminished importance of London during the nineteenth

century is most easily made in political terms. During the first half of the nine-

teenth century, most pressure groups arose from regional roots and remained

regionally distinctive. Luddism and Chartism took on different colours depend-

ing upon the locality observed, and the Anti-Corn Law League, as well as move-

ments for factory reform and for cooperative stores, had strong regional bases.

By mid-century, political leadership had migrated northward from the capital.

The Anti-Corn Law League’s victory in and John Bright’s pronouncement

that ‘Lancashire, the cotton district, and the West Riding of Yorkshire, must

govern England’ signalled a fundamental shift of influence in Britain away from

London to the Midlands and industrial North.

42

When Elizabeth Gaskell, in

Urban networks

42

D. Read, The English Provinces, c. – (London, ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

North and South, contrasted the strong, male producers and innovators of the

industrial districts with the effeminate, non-productive residents of London, she

was only echoing provincial judgements about social virtue.

Industrialisation gave new power to the British provinces and intensified local

loyalties. Cheap print spread regional novels and dialect literature to a large audi-

ence; statistical societies counted and measured the people nearby. Not only were

trades unions locally based, but factory-owning paternalists worked to turn

employees into quasi-families.

43

Despite Marxist predictions, the new proletar-

ians more easily identified with their neighbours than with French or German

counterparts.

Pride in regional difference came along with rising integration and unifor-

mity. As football, cricket and rugby professionalised, local teams drew large,

proud, socially mixed audiences. The middle-class taste for local antiquarian and

folklore societies, for local histories and maps testified to widespread enthusiasm

for identities that remained rooted in the nearby, the familiar. When the army

shifted to territorial regiments after the Boer War, men rushed to join town-

based battalions whose officers came from well-known landed and entrepreneu-

rial families. National and local patriotism fused in groups such as the Lancashire

Fusiliers.

44

The dynamics of political change shifted power back to the metropolis by the

later nineteenth century. With expansion of the national suffrage, more and more

political energy focused on events in Westminster. After the s, political

parties became more and more centralised, bringing effective control into

London and the parliamentary party. Meanwhile, city politics lost some of their

social drama as major industrialists retreated from town councils late in the

century, and the most dynamic regional figures, such as Joseph Chamberlain,

James Keir Hardie and David Lloyd George shifted their power base from the

provinces to the metropolis.

45

By the mid-twentieth century, the relentless pull

of the capital had gone far to undermine regional vitality. The growth of the state

combined with that of the media and the financial world to make London the

area of innovation and investment. In an information-driven society, there are

comparative advantages to being located close to the centres of power and action.

The vital regionalism of the early and mid-nineteenth century raises the issue

of integration: how and to what extent were regional urban networks tied to-

gether? The spread of the railroad to most corners of the realm in approximately

speeded up local patterns of circulation as well as longer-distance

exchanges.

46

London, as the focal point of north–south routes, reinforced its

Lynn Hollen Lees

43

P. Joyce, Work, Society and Politics (Brighton, ).

44

C. B. Phillips and J. H. Smith, Lancashire and Cheshire from AD (London, ), pp. –.

45

E. P. Hennock, Fit and Proper Persons (London, ), pp. –; R. H. Trainor, Black Country

Elites (Oxford, ).

46

R. Lawton and C. G. Pooley, Britain – (London, ), pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

already privileged position. The railroad illustrates a major point: regionalism

and integration into a metropolitan-centred system were parts of a common

process of growth. Each fed upon the other.

The credit system of the early industrial period shows how integration and

differentiation went hand in hand.

47

Even in the eighteenth century, private

country banks had their London agents to settle interregional debts. When joint-

stock banking expanded in England after the Banking Act of , firms that

grew first spread regionally. But at the same time, the Bank of England set up

branches in the major industrial towns, and it remained the central institution for

the rediscounting of bills. Banking transactions in the early industrial period

therefore operated on several levels: local, within and among regions and between

London and the provinces. Bank notes circulated regionally and required regular

clearing with banks of issue; commercial intelligence and exchanges of bills

flowed to and from multiple cities. Bankers contacted London to buy govern-

ment securities, to collect dividends and to finance exports to the capital. The

flow of capital from agricultural regions to industrial ones or from periphery to

the centre required multiple transactions and steps that depended upon both an

integrated region and ties to the capital.

48

Paper credit and commercial informa-

tion helped shape the ‘space economy’of the industrial period, operating through

urban networks with regional and metropolitan foci. They knit together small

regions through a web of daily transactions at the same time as they bound those

regions into a national, industrialising economy.

The growth in Britain of an active consumer culture also depended on a

complex linkage of capital and provinces. If London was the country’s shop

window, many of the products displayed had been produced in the Potteries,

Birmingham, Lancashire and Sheffield, according to information about mass

markets which came from the capital. The symbiotic relationship of metropolis

and industrial region rested on fast-flowing commercial news, consumer choices

and advertising campaigns. Each side of the exchange was dependent upon the

other. The spatial dynamics of retailing linked regionalism with larger networks

of supply. To satisfy customer demand for many items at reasonable prices,

grocers looked far and wide for goods and then sought out additional custom-

ers. To stock his shelves around , John Tuckwood of Sheffield bought from

forty different firms in seventeen cities, including London. Starting from a shop

in central Sheffield, his firm opened multiple branches in the suburbs and other

Urban networks

47

H. Carter and C. R. Lewis, An Urban Geography of England and Wales in the Nineteenth Century

(London, ), pp. –; J. B. Jeffreys, Retail Trading in Britain, – (Cambridge, ); G.

Shaw and M. T. Wild, ‘Retail patterns in the Victorian city’, Transactions of the Institute of British

Geographers, new series, (), –.

48

I. S. Black, ‘Money, information and space: banking in early nineteenth-century England and

Wales,’ Journal of Historical Geography, (), –; I. S. Black, ‘Geography, political

economy and the circulation of finance capital in early industrial England’, Journal of Historical

Geography, (), –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008