Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

for industrialists to serve on town and city councils. Unlike many continental

European countries, national politicians did not continue to rely on a local

power base. In France, the prime minister might well serve as the mayor of a

town, retaining a foothold in both local and national politics. In Britain, Neville

Chamberlain and Herbert Morrison were exceptional in moving into national

politics after a significant involvement in the government of Birmingham and

London. The growth of larger industrial concerns, with merger waves and

flotations at the end of the First World War and again around , weakened

the identity between industrialists and the local town. The external labour

market and sources of information declined in importance, with the growth of

internal training and career structures, and the development of research and

development within the firm. In all of these ways, a strong case can be made for

an erosion of the urban variable by .

However, Rodger and Reeder claim that the extent of change should not be

exaggerated in the interwar period. Although they accept that an independent

civic culture was being eroded in the northern industrial cities, they believe that

the character of industrial districts survived to the end of the period, and the

decomposition of local capital should not be exaggerated. Much depended on

the local economic base of towns. In Leicester and Nottingham, with relatively

small-scale firms in hosiery and lace, and a prosperous domestic market, the vital-

ity of the urban economy and politics continued throughout the interwar

period. Of course, in areas of deep economic depression, urban authorities with

straitened finances could do little to restructure the local economy. Even so, local

or regional issues should not be overlooked. The so-called ‘rationalisation’ of

industry to reduce excess capacity provided many opportunities for bargaining

between industrialists over the location of cuts, with their devastating conse-

quences for the urban community. These tussles were usually within trade asso-

ciations, acting through a national framework involving the Bank of England or

the central government, with little or no involvement by democratically

accountable town and city councils.

Where urban authorities did have a significant role was in the allocation of

resources for different social policies, with measurable effects on infant or mater-

nal mortality, or educational opportunity. The urban authorities were involved

in slum clearance schemes on a large scale, and were major house builders and

owners; they operated transport services and utilities, schools and libraries.

Indeed, the retreat of the middle class from urban government could be looked

at in a different and more positive way: it gave an opportunity for the working

class to take power, and to use the municipality to develop social services. The

Labour party had an important role in increasing the functions of urban govern-

ment between the wars. As Savage and Miles argue, the Labour party built up

support in the working-class neighbourhoods which had emerged in the late

nineteenth century, developing a ward organisation with female membership,

Martin Daunton

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

and so compensating for the difficulties experienced by trade unions during the

depression. This ward structure, and female participation, turned attention to the

provision of municipal services, especially for women and children. The retreat

of the urban elite meant that Labour was now the main supporter of an active

municipal culture, against the opposition of ‘ratepayers’ concerned about local

spending. Above all, Herbert Morrison presented a vision of efficient urban ser-

vices in London, providing consumers with high standards of transport, housing

and health services. Labour could present itself as a party of effective urban

government, rather than of trade union self-interest.

157

What urban authorities could not do was generate an efficient urban economy

in the face of massive depression. Declining industrial sectors such as cotton

reduced excess capacity throughout Lancashire, rather than operating at the level

of the town to restructure the local economy. Any positive action was the result

of central government policy, on a modest scale from the s and more pow-

erfully after the Second World War, to relocate industry or service employment

from the prosperous South-East and Midlands. The response was national, an

attempt to rectify the problems of distribution of employment and wealth from

outside rather than within the urban system.

(viii)

Despite the loss of urban autonomy and the mounting challenge to the urban

variable by the end of our period, the chapters in this third volume of the

Cambridge Urban History provide a convincing case that towns and cities matter.

Demographic historians realise that the decline in mortality varied between

areas, and reflected local political decisions; they accept the importance of com-

munities in explaining the fall in birth rates. Historians of welfare – of charity,

public spending and self-help – are increasingly interested in the different ‘mix’

of provision at the local as well as national level, and realise that local resources

remained vitally important throughout the period. The resolution of problems

of collective action to allow investment in the infrastructure, and to regulate ‘free

riders’ and natural monopolies, is central to the political history of the period.

The changing balance between urban diseconomies and economies helps to

explain the economic performance of Britain, and the nature of the business

concern. The ability of towns and cities to create ‘social capital’ – patterns of

sociability and associations – helped to mediate conflicts and create social stabil-

ity and economic efficiency.

These issues, amongst many others, are giving a new interest to urban history

Introduction

157

Savage and Miles, Remaking of the British Working Class, pp. –, –; see also M. Savage, ‘Urban

politics and the rise of the Labour party, –’, in L. Jamieson and H. Corr, eds., State, Private

Life and Political Change (Basingstoke, ), pp. –. On the debate on local autonomy, see

below, pp. ‒, , , ‒, ‒, .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

which was to some extent lost in the s and s, when sociologists such as

Philip Abrams cast doubt on the importance of towns as an independent vari-

able. In his view, towns were mere containers for more important explanatory

variables. Historians were warned of the dangers of ‘reification’ of the city,

making it a distinct entity; they were urged to study wider processes. But the

problem was also from within urban history, at least for the Victorian period.

Much attention was paid to the construction of towns, to the operation of the

land market and the explanation of building cycles; much less attention was paid

to the social experience of life in the new suburbs, or the ways in which different

parts of the town fitted together – how space was contested and gendered. The

rise of town planning, usually portrayed as a force for progress, lost its appeal at

a time of mounting criticism of the impact of planners on British towns and

cities. Although urban history did flourish in the s and s in the study

of medieval and early modern towns, it seemed much less exciting and challeng-

ing to modern historians.

This introduction has shown that the urban variable is again important to

modern historians, in a way which connects with the work of historians of

gender, of culture and consumption. Demographic historians are aware of the

importance of specific patterns of investment in public health and the impact on

mortality; and the distinctive patterns of marriage or fertility arising from local

labour markets and cultures. Historians of business realise that the performance

of an individual firm is shaped by the urban economy, and by the accumulation

of reputation and social capital within urban society. Historians of welfare have

abandoned a teleological account of the rise of the welfare state, and are inter-

ested in the particular mixtures of charity, self-help and public provision within

specific localities. And cultural historians, with their concern for subjectivities

and identities, are fascinated by the experience of the city. The built form is

important in terms of its iconography, the use made of the street or parks, or the

experience of travel by bus and tube. Instead of narrow accounts of the politics

of this town council or that Board of Guardians, historians are now aware of the

importance of the urban variable in understanding major issues of collective

action and investment, of dealing with market failure and the problems of exter-

nalities. As R. J. Morris has argued, nineteenth-century cities were ‘a vast labor-

atory which tested the effectiveness of market mechanisms to the limit and then

tested the operation of other ways of producing and delivering goods and

services’.

158

Martin Daunton

158

R. J. Morris, ‘Externalities, the market, power structure and the urban agenda’, UHY, (),

–.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

·

·

Circulation

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

·

·

Urban networks

Nature prepares the site, and man organizes it in such fashion as meets his desires

and wants.

Vidal de la Blache,

I

, a spider-web of railways overlay the British landmass from western

Cornwall to the eastern tip of Caithness. Tracks fanned out from London

through cities to the coastal settlements of Wales and Scotland, while branch

lines moved from mills, mines, resorts and ports to the county towns (see Map

.). Commuters rushed from suburbs into London, Glasgow and Manchester,

metropolitan centres surrounded by a dense penumbra of roads and rails.

Threadlines of transport connected a human geography of settlement. In the

eyes of the mapmaker, cities and their interconnections had tamed a world of

mountain and plain, turning natural spaces into corridors, making the remote

accessible. A century earlier, the transport network had a more truncated shape.

Around , railways linked London only to the largest county towns and the

industrial centres of the North; they had scarcely reached Cornwall, Wales or

the Scottish Highlands (see Map .). A decade later, many new lines connected

East and West, North and South, but large sections of Britain remained unreach-

able by railway (see Map .).

1

Moreover, roads had not yet swollen to accom-

modate automobiles and the needs of suburban residents. Cities, other than

London and a few regional centres, remained small in size. The urban had not

yet dwarfed the rural.

Those who mapped the growing railway network pictured British space as

organised by central cities and transport. Built landscapes dominated natural

ones. Resolutely secular and insular, they privileged the systems of exchange and

control that had arisen in a domestic capitalist economy and a nation-state. The

1

F. Celoria, ‘Telegraphy changed the Victorian scene’, Geographical Magazine (), –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Lynn Hollen Lees

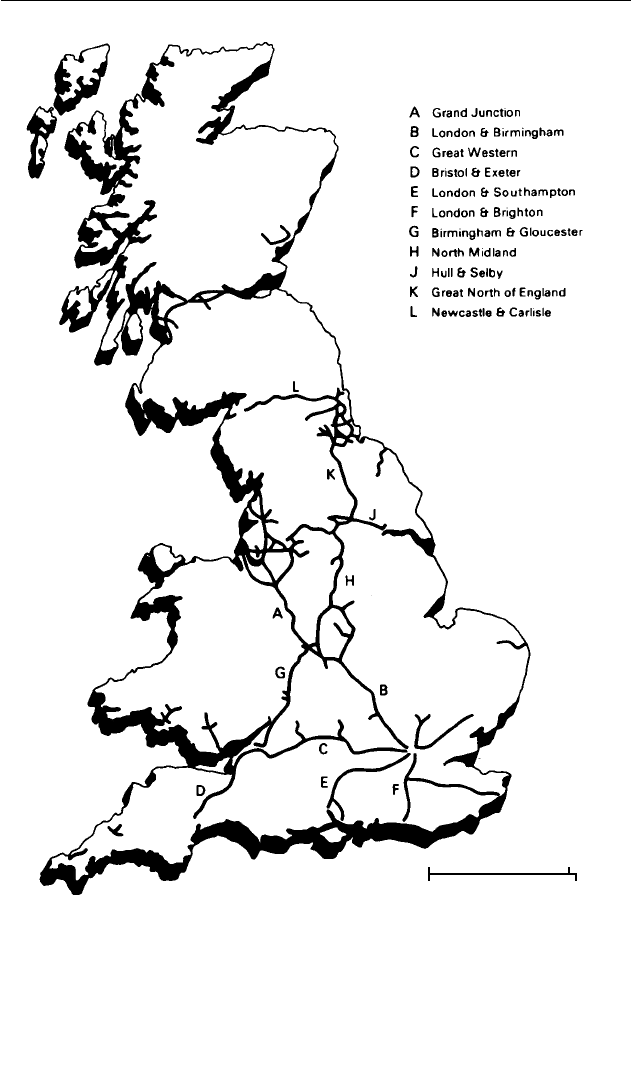

Map . The railway network c.

Source: Michael Freeman and Derek Aldcroft, Atlas of British Railway History

(London, ), p. .

0 50 miles

0 80 km

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Urban networks

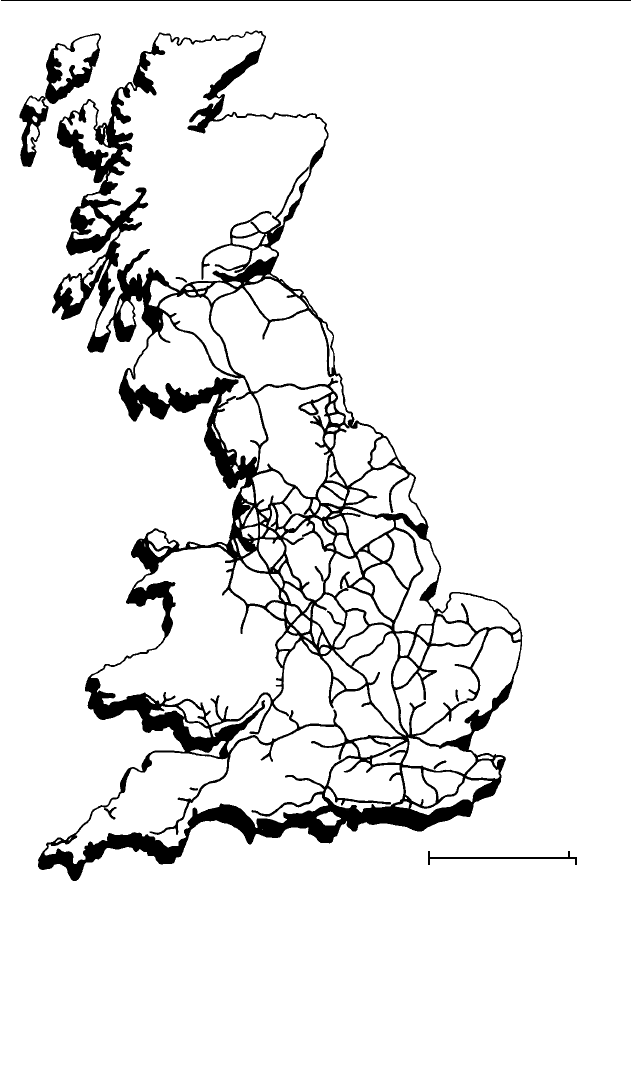

Map . The railway network c.

Source: Michael Freeman and Derek Aldcroft, Atlas of British Railway History

(London, ), p. .

0 50 miles

0 80 km

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Lynn Hollen Lees

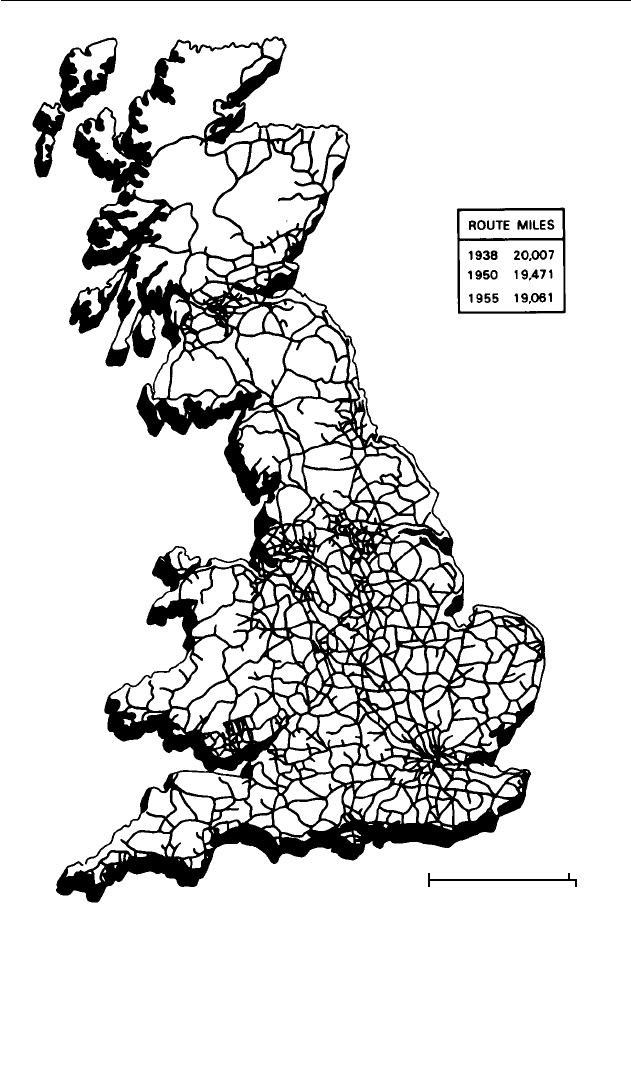

Map . The railway network c.

Source: Michael Freeman and Derek Aldcroft, Atlas of British Railway History

(London, ), p. .

0 50 miles

0 80 km

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

urban Britain they sketched captures a particular type of organisation, one that

implies stability and centrality, in which size signals complexity and influence

and in which London directed the flows of people, information and capital.

Moreover, they announce closure at the borders, as if water were a barrier rather

than a medium of circulation.

Yet urban networks transcend national borders, reaching out to Ireland and

North America, to Europe and to the rest of the globe. In contrast to closure,

these maps also signal possibility, fluidity; the pathways they depict permitted

multiple systems of circulation which could be adapted, bypassed, extended as

need and inclination dictated. Capitalist economies depend upon the mobility

of capital, labour and information, as well as the ability of capitalists to restruc-

ture modes of production and location. The continuous reshaping of urban

geographies to keep pace with economic restructuring has proved both an urban

boon and a burden. In the words of David Harvey, ‘We look at the material solid-

ity of a building, a canal, a highway, and behind it we see always the insecurity

that lurks within a circulation process of capital, which always asks: how much

more time in this relative space?’

2

These railway maps demarcate a particular period of urban and regional devel-

opment in Britain, the era of high industrialism, which was tied to specific tech-

nologies, investment choices and political arrangements. In slightly over one

hundred years, the urbanism of coal-based manufacturing for export moved

through a cycle of expansion, restructuring and decline, driven by shifts in the

capitalist economy and by changing sources of power. Large-scale industry

moved along with steam engines into an array of British cities, particularly those

near the coalfields in the North and the Midlands. Manufacturing cities, which

captured a major share of capital investment, first reaped the benefits of indus-

trial growth and then paid penalties for overinvestment in obsolescence. As

Britain industrialised and then de-industrialised, substantial changes took place

in the spatial organisation of capitalist relations of production, which were

reflected in the functioning of local geographies of manufacturing, consump-

tion and distribution, as well as in local social relations and hierarchies of power.

Unlike most of Western Europe, Britain’s urban system in the industrial era

included several manufacturing centres in its top ranks. Shifting geographies of

production as well as trade cycles have therefore had an atypically large impact

on major cities in Britain. Along with the decline of shipbuilding, coal mining,

textile production and steel manufacturing has come the relative decline of

Glasgow, Wolverhampton, Bradford and Sheffield. Whereas Manchester was the

‘shock city’ of the s because of its growth, Liverpool and Wigan filled that

function in the s as a result of rampant unemployment. Although the

modern cycle of urban industrial growth and decline extends slightly beyond the

Urban networks

2

D. Harvey, Consciousness and the Urban Experience (Oxford, ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008