Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Stephen A. Royle

Table . Population figures of small towns mentioned in the text

To w n m m

Abergavenny , , ,

Aberystwyth , , , ()

Ashby de la Zouch , , ,

Banbury , , ()

Bangor , ,

Barry n/a

Beaumaris , , ,

Beccles , , ,

Blaenavon , , ()

Braintree , , , ()

Brecon , , ,

Bridgend n/a

Bridgnorth , , ,

Briton Ferry , , ,

Bromsgrove , , , ()

Bungay , , ,

Caernarfon , , ()

Caerphilly , ,

Cardiff n/a

Cardigan , , , ()

Carmarthen n/a

Castle Donnington , , ,

Chelmsford , , ()

Chepstow , , ,

Chichester , ,

Coalville n/a

Coggeshall , , ,

Colchester n/a

Cowbridge , , ,

Cullen , , ,

Dingwall , , ,

Diss , , ,

Dolgellau , , ,

Eye , , ,

Fakenham , , ,

Fishguard , , ,

Flint , , , ()

Hallaton , , ,

Halstead , , ,

Haverfordwest , , ,

Helensburgh , , ,

Hinckley , ,

Invergordon , () , ,

Ipswich n/a

Kelso , , ,

Kenninghall , , ,

Kingston-upon-Thames , , ()

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The development of small towns in Britain

Table . (cont.)

To w n m m

Kirkwall , , ,

Leek , , ()

Lerwick , , ,

Lewes , , ()

Liverpool n/a

Loughborough n/a

Ludlow , , ,

Lutterworth , , ,

Lynn n/a

Market Bosworth , , ,

Market Harborough , , ,

Marlborough , , ,

Melton Mowbray , , , ()

Merthyr Tydfil n/a

Millport , () , ,

Mold , , ()

Monmouth , , ,

Newport n/a

Newtown , , ,

North Berwick , , ,

North Walsham , , ,

Norwich n/a

Penarth , ,

Pwllheli , , ,

Reigate , , ()

Richmond , , ()

Romford , ,

Rothesay , , , ()

Saffron Walden , , ,

Stornoway , , ,

Stowmarket , , ,

Stranraer , , ,

Stromness , , ,

Sunderland n/a

Swaffham , , ,

Swansea n/a

Swindon , , ()

Towyn , , ,

Welshpool , , ,

Woodbridge , , ,

Worsborough n/a

Yarmouth n/a

Those towns with n/a do not feature in the cohort of small towns.

Towns drop out of the cohort if they reach ,.

Source: census figures.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Stephen A. Royle

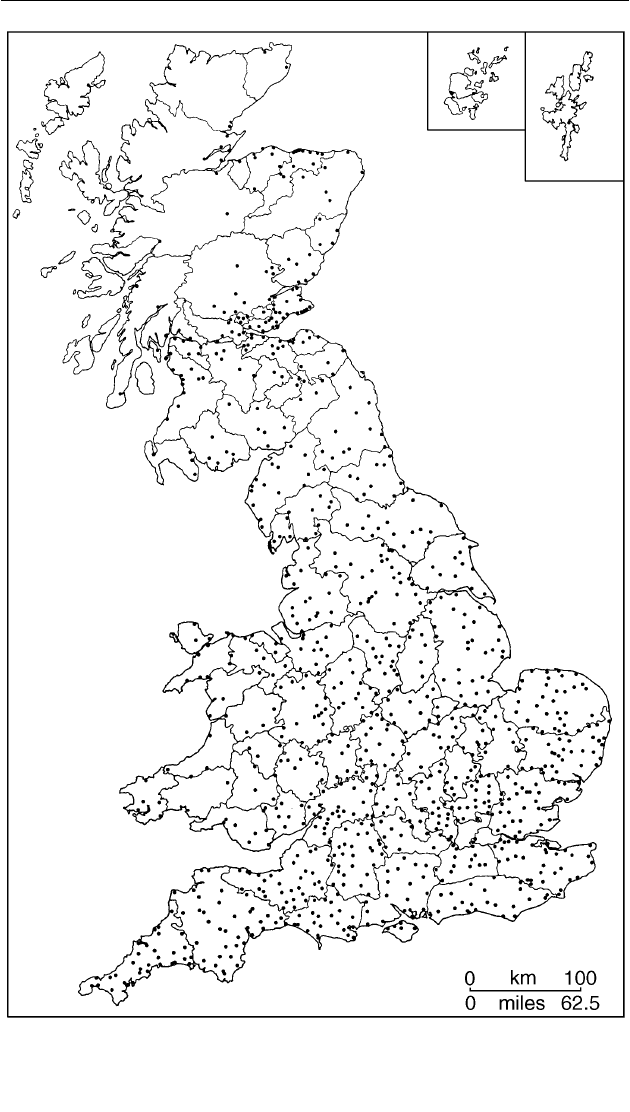

Map . Distribution of small towns (under ,) in Great Britain

(with some additional Scottish burghs for )

Source: based on census data.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The development of small towns in Britain

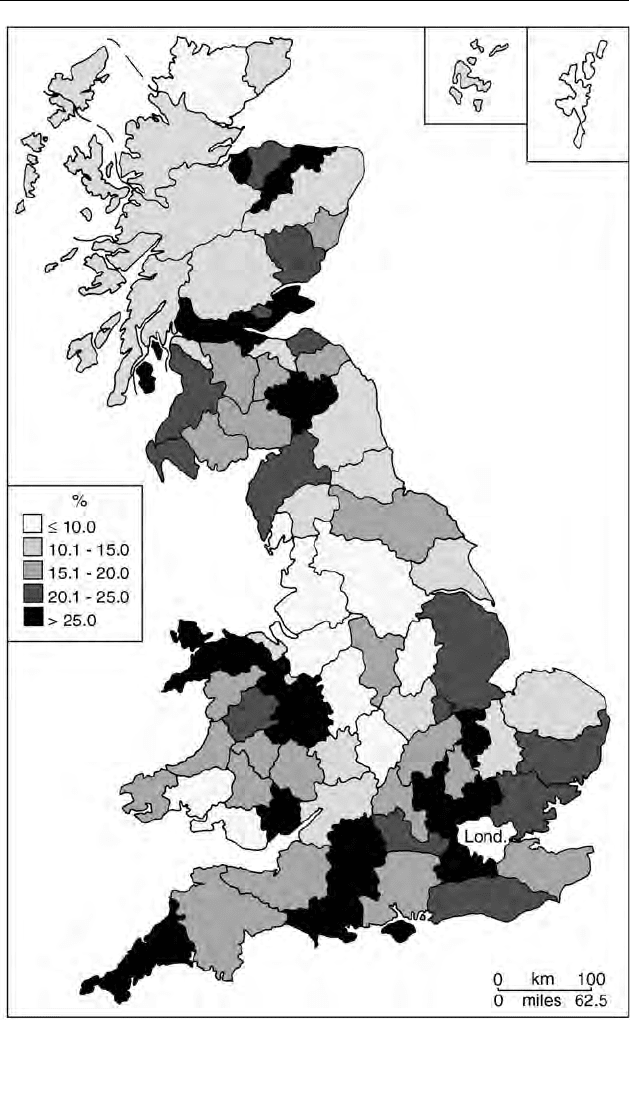

Map . Proportion of county populations living in small towns in Great

Britain

Source: based on census data.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

sorts of area can be identified where small towns were uncommon and/or

unimportant.

First, of course, there were few in the London area including Middlesex

county. Indeed, following Clark and Hosking’s ruling,

11

Middlesex was excluded

from this analysis, as were the Scottish ‘counties of the town of . . .’. Secondly,

small towns were unimportant in counties which industrialised early. These

counties formed a wishbone pattern surrounding Derbyshire, running from

Nottinghamshire anticlockwise through the West Riding of Yorkshire,

Lancashire, Cheshire, Staffordshire and Warwickshire, together with Glamorgan

in Wales. Many former market towns in these counties had already assumed

industrial functions which attracted migrants and took their population beyond

the , threshold. For example, Nottinghamshire had only six small towns

left in contrast to rural Wiltshire which, with a similar total population (,

to Nottinghamshire’s ,), had twenty-five.

A third category of area where small towns were unimportant consisted of

sparsely populated rural counties with a limited urban network – Sutherland is

the best example. Other rural counties had higher population densities asso-

ciated with a full network of market towns and these stand out as having a large

proportion of their population in small towns. Examples included Dorset,

Wiltshire and Shropshire in England; Anglesey and Caernarfon in Wales and

Nairn and Banffshire in Scotland. Other high totals were recorded in places

being affected by the initial stages of metropolitan growth as in Surrey and

Hertfordshire, or the development of small industrial towns as in the Central

Valley of Scotland. Indeed, in Scotland, much change was taking place to the

overall settlement pattern, though not all of it shows up on Maps . and ..

Shortly before the start of the study period agricultural reform, particularly in

north-east Scotland, saw people pushed from their former landholdings to new

planned villages but few became even small towns, despite pretensions – New

Leeds bears little resemblance to old Leeds.

12

However, during this fashion for

rebuilding and improvement, some substantial towns were affected. Ian Adams

details the development of Cullen where the landowner, the earl of Seafield,

ordered a land surveyor to ‘set about the removal of the present town of Cullen

and to have a new one gradually erected in order to save the heavy annual

expense it costs to keep the swarm of worthless old houses from tumbling about

the tenants’ heads’.

13

Work began in and the scale of the project can be

gauged from the fact that Cullen was in the largest of Banffshire’s small

towns.

Alan Everitt estimated that between one third and half the Victorian English

Stephen A. Royle

11

Clark and Hosking, Population Estimates.

12

D. G. Lockhart, ‘Scottish village plans: a preliminary analysis’, Scottish Geographical Magazine,

(), –.

13

I. H. Adams, The Making of Urban Scotland (London, ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

population lived in or were dependent upon provincial market towns;

14

the data

here show that overall in Great Britain in . million people lived in the

small towns, . per cent of the total population (Table .). Table . dem-

onstrates something of the variability of the economic activity of small towns at

this time by presenting information on some of those in Leicestershire, taken

from census enumerators’ books. In Leicestershire had six main market

towns: Ashby de la Zouch, Loughborough, Melton Mowbray, Market

Harborough, Hinckley and Lutterworth, arranged, in a symmetry redolent of

The development of small towns in Britain

14

A. Everitt, ‘Town and country in Victorian Leicestershire: the role of the village carrier’, in A.

Everitt, ed., Perspectives in English Urban History (London, ).

Table . British country and market town statistics –

Great Britain

Total population

a

,, ,, ,,

Population in small towns ,, ,, ,,

Number of small towns

b

()

c

,,

% in small towns . ,, . .

England

Total population

a

,, ,, ,,

Population in small towns ,, ,, ,,

Number of small towns

b

,,

% in small towns . ,,. .

Scotland

Total population

a

,, ,, ,,

Population in small towns , ,, ,

Number of small towns

b

()

c

,,

% in small towns . ,,. .

Wales

Total population

a

,, ,, ,,

Population in small towns , ,, ,

Number of small towns

b

% in small towns . . .

a

The total population excludes London, Middlesex and the Scottish ‘counties of the

towns of . . . ’.

b

Those identified as towns or burghs in the three lists by as discussed in the text

and whose population was less than ,.

c

Including the thirty-five Scottish burghs whose population was only listed from .

Source: census figures.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

the tenets of central-place theory, around the county town of Leicester.

Leicestershire’s other market towns such as Hallaton, Market Bosworth and

Castle Donnington had become less important by this period.

15

Lutterworth’s

occupational structure in reveals this town to have had a traditional role. Of

its workforce, per cent remained on the land but per cent were in services,

a distribution that placed Lutterworth within the parameters for the recognition

of a mid-nineteenth-century rural town, rather than just a village.

16

Lutterworth

still concentrated on services: ‘the local focus of human life and activities, com-

mercial, industrial, administrative and cultural’.

17

Lutterworth’s market was (and

is) on Thursdays on the spot where it had been held since and Lutterworth

retained its tradition of providing public houses, an activity described as its ‘staple

business’ for the late eighteenth century.

18

Although it had some textile workers, Lutterworth by had been little

affected by developments that elsewhere in Leicestershire were leading to func-

tional diversification of the small towns.

19

Hinckley, for example, was heavily

involved in framework knitting. At that time this was largely a domestic industry

Stephen A. Royle

15

J. M. Lee, ‘The rise and fall of a market town: Castle Donnington in the nineteenth century’,

Transactions, Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society, (), –.

16

Dickinson, ‘East Anglia’.

17

Ibid., .

18

A. H. Dyson, Lutterworth (London, ).

19

S. A. Royle, ‘Aspects of nineteenth century small town society: a comparative study from

Leicestershire’, Midland History, (–), –.

Table . Occupational structure of selected Leicestershire towns

Melton

% of workforce in: Coalville Hinckley Lutterworth Mowbray

Primary industry ....

Coal mining ....

Agriculture ....

Secondary industry, including ....

Textiles ....

Shoemaking ....

Tertiary industry, including ....

Traders ....

Professionals ....

Servants ....

Grooms ....

Others, including ....

Labourers ....

Out paupers ....

Annuitants ....

Population , , , ,

Source: census enumerators’ books.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

and Hinckley might be described as being only proto-industrial. Though it

retained its marketing functions, its major economic activity was the processing

of American cotton which certainly took it away from being a traditional country

town. Elsewhere, Loughborough had also begun to industrialise, but Ashby de la

Zouch and Market Harborough remained more traditional. Melton Mowbray

had changed, too, but still maintained rural links, its manufacturing related to

food processing (pork pies, Stilton cheese and, later, dog food) as well as the ser-

vicing and accommodation of the fox-hunting ‘“gentlemen” as they are called in

Melton Mowbray’ who stayed here in the season.

20

Hence the large number of

grooms in Melton Mowbray. Leicestershire’s small towns had been increased in

number by the development of a mining town, Coalville, which, as its popula-

tion grew, added marketing functions to its mining village activities.

21

Everitt

points out that the city of Leicester, though it dominated the higher-order

central-place activities of the county, with regard to low-order needs attracted

only one third of its clientele from the city itself whereas a market town like

Melton Mowbray attracted three-quarters of its ‘shopping population’ from the

countryside, evidence of traditional small-town–countryside interaction.

22

Lerwick, chief town of the Shetland Islands, can serve as an example of a small

Scottish town. Lerwick was a port but had also the range of occupations of a

central place and market town. The enumerators’ returns for identify some

textile working and domestic service among the women whilst ‘among the men

there were of course a number of merchants, shopkeepers and shop assistants . . .

many coopers, carpenters and ships’ carpenters. There were masons, joiners,

shoemakers, plumbers, tailors, bakers, clerks, blacksmiths, watermen, tobaccon-

ists, writers, fishermen and a mixed bag of officials. And of course there were

boatmen.’

23

For Wales, Carter points out that for a town to ‘survive depended ultimately

on the demand for urban services set up in the surrounding countryside’.

24

He

shows how the urban network bequeathed to the principality largely from the

Normans’ need to subjugate its people was affected later by the local opportu-

nities, the original network having been ‘over-elaborate for the economic con-

ditions which characterised the succeeding age’.

25

By the mid-nineteenth century marketing had developed more and, using

data from the s, Carter devised a four tier hierarchy for Welsh towns based

on functional criteria. On top were places such as Cardiff, Swansea and

Carmarthen. Lower down were small market towns acting in the traditional

manner, such as Pwllheli and Dolgellau. A contemporary description of Pwllheli

in remarked that

The development of small towns in Britain

20

J. Brownlow, Melton Mowbray, Queen of the Shires (Wymondham, ), p. .

21

S. A. Royle, ‘The development of Coalville, Leicestershire, in the nineteenth century’, East

Midland Geographer, (), –.

22

Everitt, ‘Leicestershire’.

23

J. W. Irvine, Lerwick (Lerwick, ), p. .

24

Carter, The Towns of Wales, p. .

25

Ibid., p.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

the commerce consists entirely of the importation of coal and shop goods from

Liverpool for the supply of which to the surrounding country Pwllheli forms a

great depot and is thus, though small, rendered a flourishing place. The market . . .

is well supplied . . . with all . . . kinds of provisions . . . and there being no other

market held near, it is resorted to by persons living at the furthest extremities of

the peninsula of Lleyn.

26

As Carter notes, ‘these towns were carrying out functions very similar in nature

but not in order to those of Carmarthen and the other grade towns’.

27

Lower still were ‘a large number of small market towns whose dominance was

local and limited’.

28

Everitt identified the mechanism linking the towns and their

hinterlands with his estimate that ,–, local carriers travelled the

English lanes at mid-century.

29

Town life varied with the type of town. In resort towns patronised by the

wealthy it was genteel, doubtless – consider Barsetshire’s country balls – but even

having aristocrats in residence did not guarantee a quiet life. Thus, in the fox-

hunting resort of Melton Mowbray on one occasion in , led by the marquis

of Waterford, the ‘gentlemen’ – hooligans in another age or class – in a partic-

ularly baleful drunken spree ‘painted the town red’, the incident giving rise to

the phrase.

30

By contrast, life within the traditional country town was, for most people,

hard. In Lerwick in the first half of the century:

Gross overcrowding was accepted [there were houses in with an average

occupancy of . persons]. There was no running water, no sewage, little or no

drainage, no street lighting, no planning. Every summer there was an acute short-

age of water as the wells ran dry. Increasingly the disposal – or lack of disposal –

of human excreta became a major problem. Night soil thrown daily in the lanes

added to the effluvium of the insanitary little town.

31

The town council, founded in , attempted to remedy the situation but was

handicapped by a lack of finance. They were aided from , as elsewhere in

Scotland, by the Commissioners of Police whose duties included also the levying

of rates for town improvement. Others shared the insanitary conditions of

Lerwick’s people. In Worsborough as late as night soil men were photo-

graphed in formal pose, shovels at the ready.

32

Even country towns which had

taken on additional functions to support their economy did not necessarily

prosper as a result. The present author wanted to entitle a paper on Hinckley in

Stephen A. Royle

26

S. Lewis, A Topographical Dictionary of Wales, rd edn (London, ).

27

Carter, The Towns of Wales, p. .

28

Ibid., p. .

29

Everitt, ‘Leicestershire’.

30

See Nimrod (pseudonym of C. J. Apperly), The Life of a Sportsman (London, ), for a fictional

account of such a life at Melton Mowbray; M. Frewen, Melton Mowbray and Other Memories

(London, ), for the autobiography of one who actually lived that life and Brownlow, Melton

Mowbray, for the local historian’s view.

31

Irvine, Lerwick, p. .

32

Reproduced in the Local Historian in .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

the s with a contemporary quotation: ‘the town is certainly in a stinking

state’ but was overruled by a sensitive editor who required him to settle for ‘the

spiritual destitution is excessive – the poverty overwhelming’.

33

The poverty,

which presumably worsened the stink, was caused by a downturn in demand for

the town’s principal product of cotton stockings, made largely on domestic

frames. An anonymous poet captured the mood of Hinckley at this period:

A weaver of ’inckley sot in ’is frame

’is children stood mernfully by,

’is wife pained with ’unger, near naked with shame,

As she ’opelessly gazed at the sky.

The tears rolling fast from ’er famishing eyes

Proclaimed ’er from ’unger not free,

And these were the words she breathed with a sigh,

‘I weep, poor ’inckley, for thee’.

34

In the same decade the market town and silk manufacturing centre of Leek in

Staffordshire was involved in Chartist unrest; in the s there had been strikes

by both handloom weavers and mill hands protesting about conditions.

35

However, perhaps if only to the jaded city dweller, the country town of the

nineteenth century had attractions because of its continuing localism. In mid-

century it seemed still to have a balance between

rural backwardness and city discomfort. Here . . . freedom and enterprise would

obtain still but viciousness would be neutralised by a stability and civic-minded-

ness fed from deep wells of continuity and convention. The reason was that most

families would be native to the community. Social and religious teaching would

be heeded; personal and class co-operation would be a habit.

36

Henry James had a fondness for Ludlow in the s, ‘a town not disfigured by

industry “[which] exhibits no tall chimneys and smoke streamers, no attendant

purlieus and slums’’’,

37

though, by that time, Ludlow, like Hinckley, Leek and

others, did have an industrial sector, in malting, glove making and paper manu-

facturing. That much small-town industry was often either domestic or traditional

and rurally linked (such as food processing, including brewing) did not necessar-

ily mean that conditions were good. In Bromsgrove nail making, button making

and cloth manufacture in small workshops in courts and rows behind the major

streets produced conditions of employment ‘generally of the scraping and sweated

sort, exploiting in-migrants from the countryside’.

38

This mention of the courts

and rows leads into a consideration of the internal layout of these small towns.

The development of small towns in Britain

33

S. A. Royle, ‘“The spiritual destitution is excessive – the poverty overwhelming”: Hinckley in

the mid-nineteenth century’, Transactions, Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society,

(–), –.

34

Cited in H. J. Francis, A History of Hinckley (Hinckley, ), p. .

35

M. W. Greenslade, ‘Leek and Lowe’, in VCH, Staffordshire, , pp. –.

36

P. J. Waller, Town, City and Nation (Oxford, ), p. .

37

Ibid., p. .

38

Ibid., p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008