Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

completed under the Artizans’ and Labourers’ Dwellings Act () in .

68

From the s to the First World War many large cities and a few smaller towns

provided some local authority housing, but the amount was tiny in relation to

the size of the housing problem faced in industrial towns.

Motives for the provision of social housing by local corporations in the nine-

teenth century were complex and variable.

69

They combined self-interest,

spurred on by fear of disease and working-class revolution, with genuine

concern for living conditions experienced by the poor (expressed most clearly

by local campaigners with first-hand experience of urban slum conditions), and

political expediency. Since the cost of all schemes had to be borne by ratepay-

ers, and many ratepayers were also slum landlords who stood to lose by slum

clearance schemes, objections to reform were considerable. However, by the

s there was grudging acceptance that the private market was failing to

provide adequately for low-income families and that, for a variety of reasons,

there should be some (preferably temporary) intervention by the state. Following

the First World War the scope and nature of social housing provision by local

authorities changed radically with national legislation from requiring local

authorities to survey housing need and provide council housing with most of

the cost provided through national taxation. Whereas prior to most munic-

ipalities had demolished more houses than they built, and thus exacerbated the

housing crisis for the poor, after the scale of house construction increased

dramatically (Table .).

70

Explanation of increased state involvement in housing provision is complex

and, in detail, beyond the scope of this chapter. Although the First World War

acted as a catalyst, concern about urban housing conditions was of much longer

standing. Decline in the privately rented sector, temporary collapse of the private

building industry and genuine concern about working-class protest over housing

conditions all contributed to the decision by Lloyd George’s Liberal government

to pass new national housing legislation in . Whereas in the nineteenth

century the small amount of council housing constructed was designed for the

very poor who were dispossessed from slum clearance schemes, after the

focus shifted to general-needs provision, designed to meet the housing require-

ments of a much broader spectrum of the working classes. This continued, with

changes in the quantity, quality and financing of schemes until when new

legislation again focused attention on slum clearance and rebuilding in urban

Colin G. Pooley

68

C. G. Pooley and S. Irish, The Development of Corporation Housing In Liverpool – (Lancaster,

); C. G. Pooley, ‘Housing for the poorest poor: slum clearance and rehousing in Liverpool,

–’, Journal of Historical Geography, (), –.

69

S. Lowe and D. Hughes, eds., A New Century of Social Housing (Leicester, ); Pooley, ed.,

Housing Strategies, pp. –; M. J. Daunton, ed., Councillors and Tenants (Leicester, ).

70

M. Swenarton, Homes Fit for Heroes (London, ); Daunton, ed., Councillors and Tenants; J. A.

Yelling, Slums and Slum Clearance in Victorian London (London, ); Yelling, Slums and

Redevelopment.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

areas. Following the Second World War, when housing conditions had been

exacerbated by the wartime cessation of house construction and by the effects

of bomb damage, attention again shifted to general-needs housing with both

Labour and Conservative governments committed to a high output of dwellings

in both the private and public sectors in the s and s.

Council housing in Britain has taken a variety of forms. Before the First

World War most corporation schemes for social housing were tenement blocks

on central sites close to the main centres of industrial employment. Only in

London, where central land values were prohibitive, did early schemes take the

form of lower-density suburban building. Although some tenement blocks were

large, and somewhat bleak and overpowering, others were smaller and had more

subtle design features. Under the legislation of corporations were required

to build at low density on suburban sites. Most properties were good-quality

three-bedroom semi-detached or terrace houses, though the space and amen-

ities provided were gradually reduced during the s as subsequent legislation

reduced costs. From , although some general-needs provision continued,

most housing was provided for slum clearance tenants. This either took the form

of relatively small and cheaply built suburban housing, often inconveniently

located away from transport routes and amenities, or of forbidding five-storey

tenement blocks built on clearance sites in the city centre. These had the

Patterns on the ground

Table . Slum clearance and rebuilding in Liverpool –

Total houses Total houses % of houses erected

Years demolished erected built by corporation

a

– , , .

–, , .

– , , .

–, , .

– , , .

–, , .

– , , .

– , , .

– , , .

– , , .

– , , .

–, , .

– , , .

a

Includes houses erected by Liverpool corporation outside the city boundary.

Sources: Annual Reports of the Medical Officer of Health (Liverpool).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

attraction of proximity to central sites of employment, and of retaining links to

a local community, but high-density living in flats with some communal facil-

ities did not suit all tenants. Following the Second World War both general-

needs housing and slum clearance schemes were continued from the s, with

large-scale suburban estates and inner-city high-rise blocks developed in subse-

quent years. Cumulatively, this building activity had a massive effect on the form

of cities, transforming central areas through slum clearance and redevelopment

and contributing to suburban sprawl through the development of peripheral

estates.

71

Although in theory social housing was provided for those in most housing

need, who were not adequately catered for in the private housing market, in

practice this was not always the case. In the late nineteenth century, ratepayers

were persuaded to underwrite housing schemes on the assumption that they

would be self-funding. In many cases schemes were eventually a charge on the

rates, but in theory at least rent income was supposed to cover loan charges and

maintenance costs. This meant that councils had effectively to operate as private

landlords and ensure that rental income was secure. Thus in Liverpool, for

instance, although tenants dispossessed from slum housing were accommodated,

the manager of Artizans’ Dwellings selected those tenants who had the most

secure employment and who conformed to corporation ideals of good tenants.

Others were left to crowd elsewhere in the privately rented housing stock, and

anyone who failed to pay rent was quickly evicted. The same principles contin-

ued after . General-needs housing was not meant to provide accommoda-

tion for the poor, but to house the deserving working class who were forced into

sub-standard rooms by the post-war housing crisis. In theory, the poor would be

helped by vacated property filtering down to those in most need. Housing linked

to slum clearance schemes in the s was less selective, and councils were

obliged to provide some housing for all dispossessed tenants who wanted such

accommodation, but there is evidence that those who were considered the great-

est risk were put in older Artizans’ Dwellings, rather than new flats and houses,

and others excluded themselves from council schemes on the grounds of cost.

Access to most public housing schemes was thus restricted in some way, with

those most disadvantaged being thrown back on the declining privately rented

sector.

72

The effects of these developments on tenants, and the ways in which new

housing schemes affected communities and changed the everyday use of space,

Colin G. Pooley

71

Pooley, ‘Housing for the poorest poor’; J. Melling, Housing, Social Policy and the State (London,

); Yelling, Slums and Slum Clearance; Yelling, Slums and Redevelopment; Young and Garside,

Metropolitan London; Swenarton, Homes Fit for Heroes; Daunton, ed., Councillors and Tenants; Pooley

and Irish, The Development of Corporation Housing; A. Sutcliffe, Multi-Story Living (London, );

Merrett, State Housing; P. Balchin, Housing Policy (London, ).

72

Pooley and Irish, The Development of Corporation Housing; Pooley, ‘Housing for the poorest poor’;

Pooley and Irish, ‘Access to housing’; C. G. Pooley and S. Irish, ‘Housing and health in Liverpool,

–’, Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, (), –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

can be illustrated through three case studies which examine the life cycle of

different types of social housing. These examples are drawn from corporation

housing built under local schemes from the s, good-quality suburban

housing built under the Addison Act of , and inner-city tenements built in

the s. All three case studies are drawn from Liverpool which had a more vig-

orous programme of public housing than many cities and for which detailed

information exists.

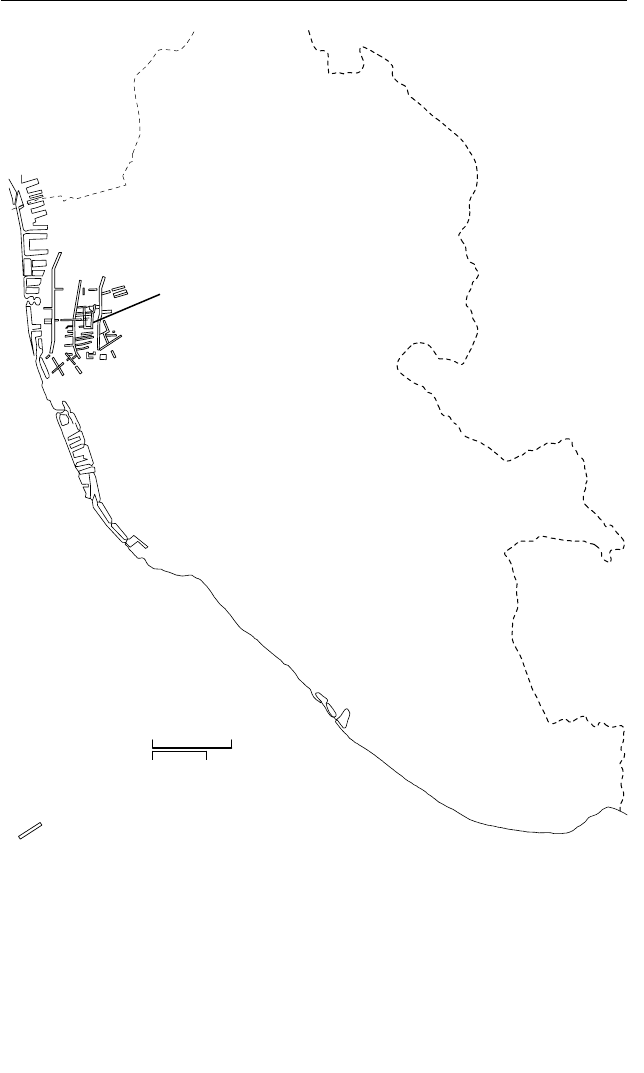

Liverpool corporation built a total of , dwellings under local schemes

before . Gildarts Gardens, begun in and completed in a series of stages

by , was among the larger schemes, eventually providing flats of various

sizes. As with other such schemes the blocks were built on land close to the

dockside and city centre, which had been cleared of slum housing, and follow-

ing the corporation’s policy of restricting dwellings to those dispossessed almost

all the initial tenants came from surrounding streets (Figure .a). In rents

for rooms in these dwellings ranged from s. d. (.p) for a one-room flat on

the third floor to s. d. (.p) for four rooms on the ground floor. Household

heads worked predominantly as dock labourers, general labourers, seamen and

carters in , but there was a vacancy rate of over per cent in every year

from to and in some years the corporation was losing as much as a

quarter of rental income through empty flats and irrecoverable arrears. The

policy of selecting only ‘a better class of dispossessed’ for the dwellings meant

that they were very hard to fill and that, although most tenants had unskilled and

casual work, they were not drawn from the most needy members of society.

73

Most families moving into the dwellings previously lived in one or two rooms

in the private sector and, although corporation tenements were new, in many

respects they offered a similar living environment. They were criticised at the

time for a lack of amenities (many were built cheaply with shared facilities and

no hot water supply) and due to the relatively high rents many families occupied

only one or two rooms. Between and overcrowding in corporation

property was a frequently reported problem.

74

Levels of crowding, use of space

and links to the local community would thus have changed little for most tenants

of the new dwellings. Whilst some families settled and remained in corporation

dwellings for many years, the high vacancy rate reflected not only the difficulty

that the corporation had in finding tenants, but also the fact that many left

quickly due to high rents and an oppressive management regime imposed by the

corporation. Such families were forced back into private rooms in the inner

city. In the s and s, as new corporation housing became available, many

families requested transfers out of old dwellings to new council flats and houses

(Table .). A block such as Gildarts Gardens thus rapidly became marginalised

Patterns on the ground

73

Liverpool Council Proceedings (–), p. ; Annual Reports of the Manager of Artizans’

and Labourers’ Dwellings (Liverpool); Annual Report of the Medical Officer of Health

(Liverpool, –), p. .

74

Annual Reports of the Medical Officer of Health (Liverpool, –).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Colin G. Pooley

(a)

Previous address (street) of tenants 1900–7

0

1 mile0

1 km

Gildarts Gardens

Figure . Origins of tenants moving to new local authority housing in

Liverpool

(a) Gildarts Gardens (built ‒)

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

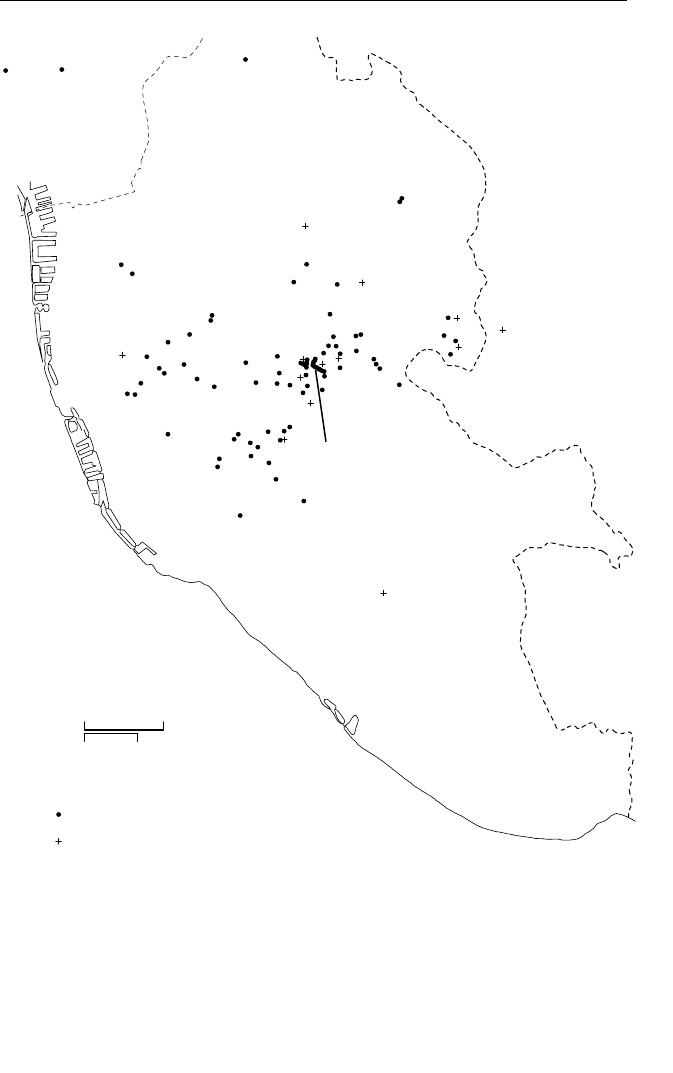

Patterns on the ground

First tenants (66 + 1 unlocated)

Subsequent tenants (15)

(b)

0

1 mile0

1 km

Davidson Road

Figure . (cont.)

(b) Davidson Road, act (non-parlour houses)

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

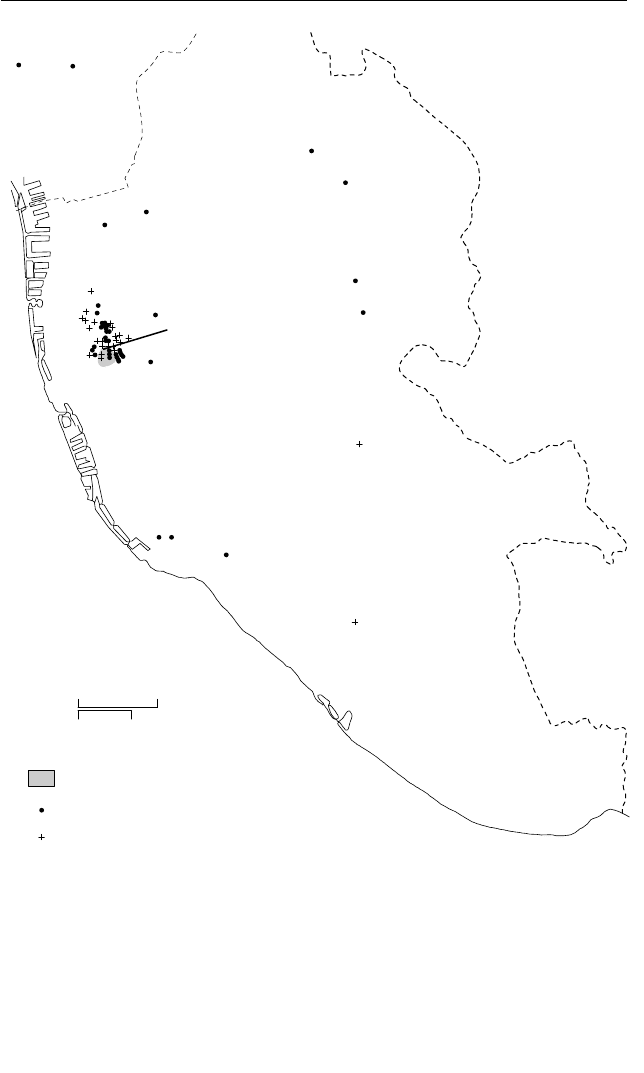

Colin G. Pooley

Cluster of 108 first tenants

Other first tenants (24)

Subsequent tenants (40 + 4 internal moves)

(c)

0

1 mile0

1 km

Gerard Gardens

Figure . (cont.)

(c) Gerard Gardens, act (tenements)

Source: C. G. Pooley and S. Irish, The Development of Corporation Housing in

Liverpool, – (Lancaster, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Patterns on the ground

Table . Characteristics of tenants of selected Liverpool corporation estates

c. –

Suburban Suburban Inner-city

Pre- -room -room tenement

housing

a

act

a

act

a

act

a

A. Household characteristics

Mean household size ....

% household heads (hh) female ....

% hh in non-manual work ....

% hh in skilled manual work ....

% hh in semi-skilled work ....

% hh in unskilled work ....

% hh employed on docks ....

% hh employed in commerce ....

% hh employed by corporation ....

Mean household income (pw) £. £. £. £.

B. Characteristics of corporation house

Mean weekly rent .p .p .p .p

Mean number of rooms ....

Mean length of occupancy . yrs . yrs . yrs . yrs

C. Characteristics of previous house

Mean weekly rent .p .p .p .p

Mean number of rooms ....

Mean length of occupancy . yrs . yrs . yrs . yrs

% moving due to demolition ....

% moving due to transfers

b

....

Sample size (households)

a

Pre- properties in eleven different inner-city locations; act houses on the

Lark Hill estate; act houses on the Norris Green estate; act tenement:

Gerard Gardens.

b

% of households moving from one corporation property to another through transfers

or exchanges.

Sources: Liverpool corporation housing records. Data relate to all tenancies starting

prior to . Household details are characteristics at the start of the tenancy.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

in the city’s housing system, containing those who could not move to better

accommodation, and used as a dumping ground by the corporation for tenants

that it had to house but did not want to put in newer property. Thus as the envi-

ronment of the inner city spiralled into decline, so too the community in a block

such as Gildarts Gardens disintegrated, and many of those left behind must have

felt increasing alienation from the locality in which they had spent most of their

lives.

The development of suburban council estates made a massive impact on

Liverpool’s urban structure with , houses built in the suburbs to .

The Larkhill estate was one of the larger developments with , houses erected

by , the majority consisting of larger parlour houses built under the Addison

Act of . Rents for these houses of three bedrooms and two living rooms

were around s. (p) per week inclusive of rates in the period to ,

an outlay which was above most rents in the private sector and comparable with

the cost of mortgage repayments on a similar property. Not surprisingly, most

tenants were in skilled non-manual or manual occupations and had previously

lived in good-quality housing elsewhere in the city. Whereas the mean number

of rooms in the previous residence of all tenants of pre- corporation prop-

erties up to was only ., for tenants of parlour houses on the Larkhill estate

it was . (Table .). Suburban corporation tenants were both self-selected (in

terms of their perceived ability to pay high rents and commuting costs to city-

centre places of work), and selected by the corporation in terms of their ability

to pay and suitability as tenants.

75

It might, therefore, be suggested that such fam-

ilies would have had little difficulty adjusting to life in the suburbs, but this was

not always the case. Relocation to suburban corporation property usually meant

leaving behind friends and relatives in other parts of the city and, as most tenants

in suburban streets were drawn from a large number of previous locations, it was

difficult to reconstruct communities in the suburbs (Figure .b). For some, the

increased space of a large house and garden posed difficulties ranging from simple

lack of furniture, to disorientation and isolation in an environment which was

perceived as unfriendly and, at least initially, lacked transport and amenities. A

tenant on the Norris Green estate in Liverpool recalled: ‘You see there wasn’t

any doctors, clinics or anything at first so it means that you had to travel for

everything, but the problem was there wasn’t any trams to take you. It got a lot

of people down and they didn’t stick it.’

76

There were many complaints about the levels of social and other facilities on

the new suburban estates. Although land was laid aside on all estates for the pro-

vision of shops, schools and churches, development of these facilities usually

lagged behind houses. For instance, in , residents on the Speke estate com-

Colin G. Pooley

75

Liverpool Housing Committee Minutes; Pooley and Irish, The Development of Corporation Housing;

Pooley and Irish, ‘Access to housing’.

76

McKenna, ‘The suburbanisation’, .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

plained that, although they had lived there for two years or more, only three

small shops had been provided. Similarly, on the Sparrow Hall estate there were

bitter complaints in that no Roman Catholic school had been built despite

the fact that the population rehoused from the inner city was almost entirely

Catholic. Recreational and leisure facilities were particularly slow to develop on

all estates, with public houses banned from many estates in the s and s

on moral grounds, and few community centres, clubs or other facilities despite

energetic lobbying from local councillors and tenants’ associations. Thus in

a report highlighted the lack of facilities for young people on suburban council

estates, estimating that the Walton Clubmoor estate contained residents

aged ten to eighteen years who had nothing to do except attend church activ-

ities or cinemas. It was argued that provision of a youth social centre was urgently

needed to prevent the estate becoming a ‘breeding ground for social discon-

tent’.

77

These examples show clearly the ways in which private and public space

continued to be linked, with lack of amenities creating the potential for social

tension within the new communities. The increased cost and lack of facilities

were too much for some families and they returned to inner suburban housing,

but the majority of tenants did settle quite quickly on an estate such as Larkhill,

surviving the recession years, and eventually creating new stable communities.

Of those who did not leave quickly, most remained in the same house for a long

time, and in the period after the good-quality estates built under the

act were by far the most attractive corporation stock in most cities with tenan-

cies often passed from parents to children. In contrast, suburban estates built

under slum clearance schemes in the s took much longer to stabilise.

Under the Greenwood Act of Liverpool corporation built , units

in flats, mostly in the city centre. Gerard Gardens, containing units built

– on land made available through slum clearance in the north-central part

of the city, was typical. As with the early Artizans’ Dwellings most tenants came

from the surrounding streets (Figure .c) and there was thus some chance that

local communities would survive the dislocation of slum clearance and rebuild-

ing. The corporation had an obligation to offer housing to all those dispossessed

through slum clearance and the occupational profile of tenants in Gerard

Gardens was quite different from that of the Larkhill estate. Over per cent of

household heads were in semi-skilled or unskilled work, their mean income was

less than half that of suburban tenants, . per cent moved due to the demoli-

tion of their previous homes and, on average, they had lived previously in only

. rooms. Although rents were mostly higher than in previously occupied pri-

vately rented housing, ranging from s. d. (p) for a bed-living room to s.

d. (.p) for a five-bedroom flat, they were much lower than in the suburbs

(Table .).

78

Patterns on the ground

77

Pooley and Irish, The Development of Corporation Housing, pp. –.

78

Ibid.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008