Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century cities seemed to stand in stark con-

trast: densely and often irregularly built, lacking in open space, with little coor-

dination of land uses. The worst parts, built with a mixture of courts, back to

backs and non-residential uses, seemed often to reflect a fragmentation of prop-

erty. Particular parcels, often of small extent, became units of urban develop-

ment, their size and shape carrying forward elements of the pre-urban cadaster

into a chaotic new townscape.

19

Olsen’s link between the management of landed estates and the development

of town planning was certainly a correct one. For although town planning had

many points of origin, the careful regulation of space through the social grada-

tion of residence and ordered disposition of land uses, which became established

as good practice on these estates, also passed into planning doctrine. Moreover,

the subsequent development of Olsen’s studies, reinforced by other scholars, par-

alleled the changing prestige of town planning between the s and the

s.

20

The extent to which it was possible, or even desirable, for a single large

authority to exercise control over land was put into doubt, the piecemeal and

informal became more fashionable, and above all the market was resurrected as

a reputable institution and consumer demand established as the vital factor deter-

mining outcomes. Locally, the extent to which landed estates could produce

exemplary development was seen to depend on the position in the market that

particular projects could command. Nationally, Martin Daunton showed that

variations in wage levels were a key factor in understanding regional variations

in building standards.

21

As the mechanisms of development were studied more carefully it became

evident that a chain of agencies and multitude of hands contributed to the build-

ing of Victorian cities.

22

In this schema the case in which the landowner acted

also as developer and tightly controlled the supply chain was only one possibil-

ity. More usually, there were separate developers and builders, and an important

ingredient in the success of such agencies was to sense what the market would

stand in particular localities and at particular times. The development role was

especially important since the layout and physical preparation of land for build-

ing necessarily involved an orientation towards a particular market. Moreover,

there was in this process the possibility of transcending the limitations of separ-

ate landownership. New building regulations had their effects in the late

Victorian period, and may also have been a factor that encouraged the greater

use of specialist developers. In any event, the polar cases of organised coherent

J.A.Yelling

19

M. J. Mortimore, ‘Landownership and urban growth in Bradford and its environs in the West

Riding conurbation, –’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, (),

–.

20

D. Cannadine, Lords and Landlords (Leicester ); F. M. L. Thompson, Hampstead (London,

).

21

Daunton, House and Home, pp. –.

22

H. J. Dyos, Victorian Suburb (Leicester, ); D. Cannadine and D. Reeder, eds., Exploring the

Urban Past (Cambridge, ), pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

development through a large landed estate and undesirable irregularity elsewhere

became less prominent.

In north Leeds agricultural estate owners rarely engaged in building estate

development after , and even before this date the prevalence of freehold

tenure meant that land was often sold for development.

23

Several large estates

made attempts to let land on other tenures, but competition from rival develop-

ers meant that prospective purchasers were usually able to insist on freehold

tenure. Similarly, the Ramsden estate in Huddersfield, despite its large size and

strategic position in the town, was unable to impose year leases in the s

and had to adopt year leases instead.

24

By contrast, there was always a ready

market for freehold land even in towns dominated by leasehold tenure. It would

appear therefore that leasehold tenure needed to be established under conditions

in which competition from freehold could be controlled. This was most likely

to be the case early in urban development, and the notable contrasts between

major English cities in the nature of their tenure were clearly evident in the late

eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

25

In Scotland, certainly, a distinctive

tenure, the feuing system, was already established which contrasted with the

English types. Richard Rodger’s attempt to link this feature to the particular

form and density of Scottish towns constitutes perhaps the most notable attempt

in recent literature to preserve a strong role for supply factors in the complex

interaction of causes affecting urban development.

26

Despite the fact that, according to Jane Springett, the Ramsden estate was

‘brought to heel’ by the petite bourgeoisie in the s, it none the less had a dis-

cernible impact on the town through the controls exerted over the development

of the estate. The result was that a lesser proportion of lower-class property was

built, but to some extent at least at the expense of higher rents and greater

crowding of dwellings than in neighbouring towns. Elsewhere, too, large estates

were frequently associated, other things being equal, with higher-value residen-

tial property, while the reverse was true on fragmented lands. Even in the East

End of London large estates such as the Mercers were able to some extent to

shape their own market.

27

They were able to do so because of the quality of the

initial building, and because of the controls that were exercised over tenancy and

land use. Clearly, controlled development could not transcend the larger effects

of class or income, and beyond a certain point insistence on high-quality build-

ing led to rents which suppressed demand and resulted in housing problems

Land, property and planning

23

C. Treen, ‘The process of suburban development in north Leeds –’, in F. M. L.

Thompson, ed., The Rise of Suburbia (Leicester ), pp. –.

24

Springett, ‘Land development’, p. .

25

C. W. Chalklin, The Provincial Towns of Georgian England (London, ); C. W. Chalklin, ‘Urban

housing estates in the eighteenth century’, Urban Studies, (), –.

26

Rodger, ‘Rents and ground rents’, pp. –.

27

M. Paton, ‘Corporate East End landlords: the example of the London Hospital and the Mercers

Company’, LJ, (), –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

emerging in other ways. None the less, it remained the case that, other things

being equal, higher-quality residence was associated with a more controlled

environment. Also, since it is generally accepted that the imposition of greater

controls over development and land use was usually not immediately advanta-

geous to the landowner, something should still be retained of the notion of long-

term versus short-term advantage and of the importance of non-economic

motives in development.

It must always be borne in mind that conditions at the edge of towns were

always very variable both in terms of landownership and in terms of physical dis-

position, layout and land uses. None the less, as a general rule the trend was

towards division from larger physical units towards smaller plots, and correspond-

ingly towards increasing fragmentation of property. C. Treen’s list of major

developers operating in north Leeds – involved purchases of up to

acres ( ha), but the largest landowners sold more than twice as much land, and

in the case of the Brown estate received a gross income of £,.

28

Real

estate subdivision was, however, more profitable than building itself, which was

subject to intense competition. The presence of a large number of small units

with low capital in the building industry meant that there was a high demand

for small lots, which when professional services and physical site preparation

were added produced very high costs. The Brown estate trustees, selling free-

hold plots directly to builders, achieved average prices over the period

– of £ per acre. Estates which sold land for subdivision to devel-

opers in the same period achieved rather less than half this price. On the other

hand, land with only agricultural value was currently selling for only £–£

per acre. Land could be sold more quickly to developers, with fewer costs to

bear, and without engaging in all the minutiae and risks of estate development.

The passage of land from landowner to developer to builder would thus seem to

involve a progressive decline in profit made, particularly when related to the risk

and effort involved.

Similarly, it is generally agreed that the ownership of house property was rel-

atively fragmented and involved the employment of petty capital. Owners of

good-class residential property had less trouble, but relatively low rewards,

whereas towards the bottom end of the market profitability was potentially

much higher but at higher risk and requiring personal involvement.

29

To that

extent the owners of large-scale capital may be seen as subcontracting the less

profitable activities. However, a more positive view might emphasise the advan-

tages gained in property development and property ownership from local

knowledge and local connections. Indeed, local influence has been seen as

central to the condition of the petite bourgeoisie, and hence small-scale property

ownership as a factor closely related to the fortunes of this class. Such consid-

J.A.Yelling

28

Treen, ‘Suburban development’, pp. –.

29

Daunton, House and Home, pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

erations also direct attention to the manner in which the leasehold system served

to perpetuate large-scale interests in residential property. For while ratebooks

provide a list of property owners which is useful in many respects, they also tend

to mask financial realities in towns where leasehold prevailed. Well in advance

of the date at which property was due to revert to the estate, the financial

balance began to tilt towards the ground landlord. The realisable value of the

ground rents came increasingly to reflect the reversionary value, while the inter-

est of the leaseholder was correspondingly diminished. As Christopher Chalklin

put it, ‘the value of the leasehold urban estate formed in the eighteenth century

only became outstanding two or three generations later when the building leases

expired’.

30

By the late nineteenth century such estates would be at or near the

reversionary date. Undoubtedly, some large gains were made at this point.

However, the extent to which monetary expectations were realised once more

underlined the way in which the fortunes of landed estates were subject to

market and other factors over which only limited control could be exerted.

Indeed, the argument concerning the position of landed estates on the rever-

sion of urban properties tends, not unnaturally, to mirror that concerning their

role in initial development.

One advantage claimed for landed estates was that ‘a freeholder of an individ-

ual building could at best try to adapt it to the changing character of the neigh-

bourhood. A large landowner could change the character of the neighbourhood

itself.’

31

The renewal of the Grosvenor estate in Mayfair was a model of the kind

of change which such property could bring about. Partial redevelopment, seg-

regation of land uses, release of land to model dwellings companies, all required

control over a substantial area, and an ability to absorb short-term loss of

income.

32

Mere mention of the word Mayfair, however, highlights the extent to

which the decisions were necessarily affected by location and market potential.

While what happened to landed estates on reversion has been subject to fewer

studies than their original development, it seems that in most cases it made eco-

nomic sense to postpone major decisions, and relet on higher repairing leases.

Rising costs promoted the development of cheaper land on the outskirts, but at

the same time selective out-movement reduced the extent to which it was

profitable to invest in inner-urban property. This developing geography was, of

course, attributable to many factors, but it should not be excluded that condi-

tions under which property was supplied affected it at the margins. Landed

estates fostered a taste for residential areas which were socially graded and strictly

controlled in terms of their land use, but in turn such conditions were more

easily supplied in development than in redevelopment or renewal.

Land, property and planning

30

Chalklin, ‘Urban housing estates’, .

31

Olsen, Town Planning, p. .

32

M. J. Hazelton-Swales, ‘Urban aristocrats: the Grosvenors and the development of Belgravia and

Pimlico in the nineteenth century’ (PhD thesis, University of London, ); PP ,

Committee on Town Holdings, pp. ff.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

(iii)

During the late Victorian and Edwardian period economic change and electo-

ral pressures for social reform brought to prominence unorthodox doctrines

associated with the land question, the tariff question, socialism and national

efficiency. Both of the main political parties were brought into crisis by attempts

to accommodate these new tendencies with more traditional elements of their

programmes.

33

It was a variable and incomplete process, and outcomes in terms

of urban development did not have widespread effects before . Such a

context is, however, essential to understanding the nature of particular results

that were to have greater future application. It is generally accepted that

– was the formative period of modern British town planning, and

henceforth the control of land, and of land uses and land values, became of

heightened significance.

34

Equally, this was a crux period in the field of

housing policies. The period immediately before the First World War was the

first in which the main political parties could be said to have distinctive housing

programmes, and henceforth electoral outcomes would have a more direct

impact on urban development.

35

Most of the doctrines mentioned above had

some impact on housing and town planning. Land reform was, however, a dom-

inant feature in this field in the sense that it not only drew on its own body of

principles, but was the means by which other purposes could be realised

and their values absorbed. It had undoubted links with many of the novelties of

the period: the garden suburbs at Bournville, Hampstead and elsewhere, the

first garden city at Letchworth, suburban council estates and town planning

legislation.

The existence of landed estates and of the leasehold system was crucial to

the way in which the land question was conceived. It epitomised, in the

view of reformers, the control that landownership gave over those who lived

on the land, as well as a division between the productive use of land and

the ‘unearned increment’ arising from its ownership. There were, however, divi-

sions within reformist ranks not only over the degree but also the manner in

which large concentrations of property should be broken down. Some types of

land reform were aimed specifically at the special legislation that governed

such estates, as in the debate over the Settled Land Act () or leasehold

J.A.Yelling

33

Offer, Property and Politics; H. Emy, Liberals, Radicals and Social Politics – (Cambridge,

); E. H. H. Green, The Crisis of Conservatism:The Politics, Economics and Ideology of the British

Conservative Party – (London, ).

34

W. Ashworth, The Genesis of Modern British Town Planning (London, ); G. Cherry, The

Evolution of British Town Planning (Leighton Buzzard, ); A. Sutcliffe, Towards the Planned City

(Oxford, ); S. V. Ward, Planning and Urban Change (London, ).

35

J. A. Yelling, Slums and Slum Clearance in Victorian London (London, ), pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

enfranchisement.

36

Various versions of land taxation formed a second and pre-

dominant thrust of attack. The other major strand, equally old, involved some

form of collective landownership. As reflected in the Land Nationalisation

Society (LNS), this took the view that ‘the evil of the system is not that land is

held in great estates, but that it is treated as private property at all’.

37

All the same,

the LNS case was clearly related to the landed estate system since their model of

reform was essentially based on a ground landlord–tenant relationship in which

collective control replaced the private owner. The force of these divisions is

shown by LNS support of the decision of some Liberal MPs to oppose the

Leasehold Enfranchisement Bill of . However, the existence of different

strands of opinion also widened the participation in land reform. After all, some

inherent contradiction between support for landed estates and for owner-

occupation was not seen as a weakness in the Conservative ‘ramparts of prop-

erty’ strategy.

38

Land reformers found that emphasis on the maldistribution of property was

not enough to give them political impetus. Their doctrines also had to be linked

to contemporary preoccupations and observable evils. They achieved a degree

of success, and an essential unity of purpose, by promoting a key image of the

period – the congested city contrasted with the depopulating countryside. A

wide range of land reform elements could be drawn into this debate.

Economically, urban congestion was directly linked to high land values, to the

concept of urban site rent as ‘unearned increment’ and to the idea that urban

property owners were currently sheltering under a form of monopolistic pro-

tection. Politically, the extremes of urban congestion and rural emptiness could

be seen to reflect the land nationalisers’ emphasis on the control that landown-

ers exercised over their land and the conflict of interest with the tenants that

inevitably arose. It was an image that would carry a powerful mixture of conser-

vative and radical implications, and link with other rising concerns of the period,

such as the debate on ‘national efficiency’.

39

I have argued previously that a key factor in the emergence of this focus was

the failure of land reformers to make progress by directly imposing the costs of

urban improvement on landowners.

40

In the s, the Progressives on the

Land, property and planning

36

D. Reeder, ‘The politics of urban leasehold in late Victorian England’, International Review of Social

History, (), –; R. Douglas, Land, People and Politics (London, ); H. J. Perkin, ‘Land

reform and class conflict in Victorian Britain’, in J. Butt and I. Clark, eds., The Victorians and Social

Protest (Newton Abbott, ); S. Ward, ‘Land reform in England, –’ (PhD thesis,

University of Reading, ).

37

J. Hyder, The Case for Land Nationalisation (London, ), p. .

38

Offer, Property and Politics, p. .

39

P. L. Garside, ‘“Unhealthy areas”, town planning and eugenics in the slums –’, Planning

Perspectives, (), –; W. Voigt, ‘The garden city as an eugenic utopia’, Planning Perspectives,

(), –.

40

Yelling, Slums and Slum Clearance, pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

London County Council had raised the compensation and betterment issue in

its special form in relation to street improvement and slum clearance.

41

It was

argued that these public activities were carried out at great loss to the ratepayer,

because of the high cost of compensation for the necessary purchase of the prop-

erty, but that such improvements also brought betterment of property values

which largely escaped local taxation. If the costs of such schemes could not be

reduced by new legislation, then a lateral shift on to cheaper land in the suburbs

became a way in which the landlords could be outflanked, and existing site rents

brought down through a large increase in housing supply. This could accommo-

date Fabian interest in municipal administration and William Thompson’s

scheme for the organised dispersal of the population through municipal land and

building. Equally, site value rating could arguably achieve this end without public

expense, essentially by taxing undeveloped land and by reinforcing market pres-

sures to move from expensive to cheaper sites. Cheap land, the reduction of

costs, the powerful effects of competition, all connected to traditional liberal

values, and the significance given to them helps explain the way in which

Ebenezer Howard and Thompson discussed the potential impact of their

schemes on existing cities in terms of the purely beneficial effects that would

arise from major reductions in rents and property values.

42

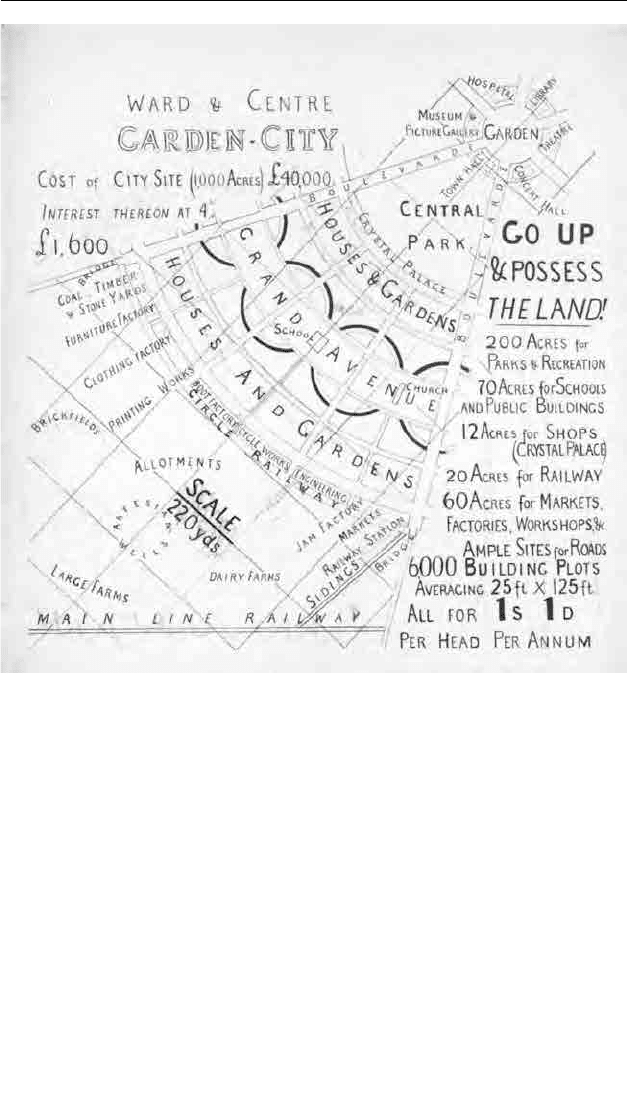

Howard’s ‘peaceful path to real reform’ is, however, most closely related to the

strand of thinking represented by the land nationalisers (Figure .). This was

particularly concerned with the social organism, and became linked to the

nascent town planning movement through the view that ‘the community as a

whole, that is to say the actual occupiers of the land in their collective capacity,

shall decide the uses to which land shall be put’.

43

Robert Beevers claims that

‘the Garden City Association was initially founded around a nucleus of members

of the Land Nationalisation Society’. This was equally true of the National

Housing Reform Council, which played a large part in the origins of the

Housing and Town Planning Act.

44

Control over land was seen to be the factor

that would release all kinds of benefits – escape from overcrowding, greater aes-

thetic beauty, more sense of community. However, there were also elements of

the programme that drew the movement closer to the great estates and to the

traditional proponents of paternalism. The LNS secretary, Joseph Hyder, wrote:

‘We have always been told by the champions of private property in land that

J.A.Yelling

41

H. R. Parker, ‘The history of compensation and betterment since ’, in Acton Society Trust,

Land Values, pp. –.

42

E. Howard, Tomorrow (London, ), p. ; W. Thompson, ‘The powers of local authorities’, in

The House Famine and How to Relieve It (Fabian Tracts , ), p. .

43

Hyder, Land Nationalisation, p. .

44

R. Beevers, The Garden City Utopia (London, ), p. ; J. A. Yelling, ‘Planning and the land

question’, Planning History, (), –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

great estates are better managed than small ones, and there is much truth in the

contention . . . the good of the estate as a whole is more likely to be kept in

mind when it is under one ownership.’

45

The LNS was therefore to accept prop-

erty fragmentation as a key cause of slums, and in the practical advance of town

planning this emphasis became still more apparent. Features of land use control

on large well-managed private estates were accepted as good planning practice,

and when town planning was officially introduced in as a limited measure

of suburban land regulation, planning schemes came into being most easily

around the core of a large estate.

Land, property and planning

45

Hyder, Land Nationalisation, p. .

Figure . Draft diagram for Ebenezer Howard, Tomorrow

Source: Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

New ways of thinking about ‘community’ were a feature of the new liberal-

ism, designed to mitigate the social effects of economic individualism while

preserving individual enterprise. Community was given a territorial focus, and

often tied to projects of land reform. Thus in Howard’s model garden city a

better environment and provision of amenities was to be merely one product of

a web of individual and collective activities and voluntary associations which

would bind the community together. These varied enterprises were to be

founded on community ownership of the land and the revenues which arose

from it. The great difficulty lay, however, in the initial purchase of this land, for

the use of private trustees as at Letchworth had obvious disadvantages. At first,

there were some signs that municipal landownership might be promoted for the

purpose. In Unionist Birmingham, John Nettlefold, inspired by the example of

Germany, proposed that ‘a Corporation cannot own too much land’, and saw

this as a basis for creating ‘a healthy happy community’ in which private persons

and public utility societies would erect houses within the framework of a plan-

ning scheme.

46

However, community landownership was never able to perform

this mediating role as the key point on which municipal activity should focus.

Opposition to any extension of municipal landownership was strongly

entrenched as Aldridge, Nettlefold and Thompson found when they tried to

link it to town planning in preparation of the act.

47

On the other hand,

municipal housing had already become an important factor. It raised problems

of an altogether different order, for it shifted the nature of municipal control

from relationships between landlords and ground landlords to relationships

between landlord and tenant. This issue increasingly became a point of diver-

gence around which political programmes were built.

In her account of the development of Huddersfield, Springett presents the

incorporation of the town as a triumph for the bourgeoisie, and for local prop-

erty interests in particular.

48

It was they who henceforth controlled the council

and, for instance, approved building regulations that were less stringent than

those that the Ramsden estate had attempted to impose. While such conflictual

relations within the world of property may not have been the norm, this situa-

tion does capture the sense in which the nineteenth-century growth in property

ownership should naturally be reflected in the composition of local councils. At

the end of the period electoral developments seemed to threaten this relation-

ship, and the activities of local councils became increasingly a focus of resent-

ment among property owners. According to authors such as David McCrone

and Brian Elliot this reflected not only the potential damage to material inter-

ests but also the loss of social status and control which even small property

J.A.Yelling

46

G. Cherry, Birmingham (Chichester, ), p. .

47

A. Sutcliffe, ‘Britain’s first town planning act: a review of the achievement’, Town Planning

Review, (), –.

48

Springett, ‘Land development’, p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

owners possessed vis-à-vis their tenants.

49

In this changing situation not only

were property interests thrown closer together, but in many ways the owners of

large estates were better placed than their smaller counterparts. They were able

to connect with some of the new developments and to attempt to mould them

in directions favourable to their interests. Smaller owners and their organisations,

however, found little in the way of strategy except a dogged emphasis on laissez-

faire and the traditional virtues of political economy. While this was perfectly

capable of winning battles it seemed to run against the tide of opinion in all

political parties that new electorates would require new ways forward.

A final point to consider is how the political developments in this period

affected the perception of supply and demand factors in urban development, and

hence the debate that was considered in the last section. They undoubtedly did

tend to suppress the significance of demand factors and to elevate land reform,

however essential, to an importance in economic, social and political life that it

could not sustain. The reasons for this were, however, deep-seated and like the

reform movements themselves strongly rooted in Victorian thought and practice.

In the first place the significance given to land partly reflected the remarkably

strong defence that had been built up against income transfers. Given increased

electoral pressures for social reform an indirect route through land was all the

more tempting because other possibilities seemed to be more effectively blocked.

In the second place, the apparent inviolability of the economic system through

the period, coupled with the importance given to paternalism, meant that there

was a strong tendency to put the blame for observed defects on particular agents

or agencies. Good property tended to be associated with good management and

poor property with bad without sufficient attention to the different markets that

were served. With the indirect method now favoured in housing and town plan-

ning, new forms stood to benefit from the contrast that would be made with the

older property and older property relationships in the existing part of cities. Not

surprisingly, when the Unionists first breached the political taboo on housing

subsidies in , one main purpose was to deflect municipal enterprise back to

the oldest and poorest properties by resurrecting slum clearance.

50

To conclude, by a series of important new developments had occurred.

There was now a practical political debate which brought into question not just

particular patches of property, but the whole pattern of urban development.

Strong connections had been made in this debate between urban form and land

values. Increased attention was given to municipal activity in the field of land

Land, property and planning

49

D. McCrone and B. Elliot, ‘The decline of landlordism: property rights and relationships in

Edinburgh’, in R. Rodger, ed., Scottish Housing in the Twentieth Century (Leicester, ), pp.

–; for tensions between landlord and tenant see D. Englander, Landlord and Tenant in Urban

Britain, – (Oxford, ); Daunton, House and Home, pp. –, sees private landlords as

falling between the interests of the main political parties.

50

Yelling, Slums and Slum Clearance, p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008