Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

workforce. Underemployment remained an important strategy into the interwar

period, particularly in the Midlands coalfields.

66

However, in most of the export

coalfields full redundancy had become the dominant labour market response to

the slump. The coal industry was hit early and long-term unemployment, con-

ventionally defined as continuous unemployment for more than a year, remained

a serious problem in the industry throughout the s. The Pilgrim Trust’s Men

Without Work report suggested that long-term unemployment in was

‘mainly a localized abnormality of coal-mining districts dependent on mines

abandoned or permanently closed’.

67

While other industrial groups also suffered

severe long-term unemployment in the s, miners remained the largest single

occupational group among the long-term unemployed; by , per cent of

coal miners had been unemployed for more than a year.

68

The changing nature of economic distress in the coal industry had important

ramifications for other labour markets. The sheer size of the mining workforce

meant that the flows of labour into and out of the industry were among the most

significant influences on patterns of internal migration.

69

Mining employment

declined significantly from the mid-s with almost half a million men leaving

the industry between and . Employment declined less dramatically in

the late s and s. Miners have had a reputation for geographic and occu-

pational immobility, but the exodus from the declining export coalfields was

substantial. Although there was government encouragement through the indus-

trial transference scheme, most of this migration was voluntary. Migrants tended

to be younger and more economically active than the general coalfield popula-

tions, and their loss significantly altered the age structures of coalfield settle-

ments. Between them the South Wales and Northumberland–Durham coalfields

are estimated to have lost , people between and .

70

Some miners

moved to pits in Nottinghamshire, South Yorkshire and Kent, but there was also

considerable migration into the new industries of Greater London and the

South-East of England. Migrating miners played a major part in industrial and

urban restructuring.

(v)

The largest urban labour market for women was in domestic service. Through

the nineteenth century service became increasingly dominated by women

David Gilbert and Humphrey Southall

66

C. P. Griffin, ‘“Three days down the pit and three days play”: underemployment in the East

Midlands coalfields between the wars’, International Review of Social History, (), –.

67

Pilgrim Trust, Men without Work (Cambridge, ), p. .

68

Ibid., p. .

69

D. Friedlander and R. J. Roshier, ‘A study of internal migration in England and Wales: Part ’,

Population Studies, (), .

70

B. Supple, The History of the British Coal Industry, vol. : –:The Political Economy of Decline

(Oxford, ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

workers. At the beginning of the century there were around eight women ser-

vants for every male servant; by the end of the century the ratio was over twenty

to one. However, the absolute numbers of men in domestic service did not

decline significantly, and men’s privileged position in service was reinforced.

Within residential service butlers were usually paid more than cooks or house-

keepers, and coachmen, grooms and footmen more than even the most experi-

enced of housemaids.

71

Live-in maids and non-residential workers in domestic

service were invariably women, and usually very poorly paid. The gendered

nature of this labour market makes it hard to estimate its size. The closeness

between paid service and those tasks traditionally defined as women’s unpaid

domestic labour meant that this work was often regarded as marginal to conven-

tional waged labour markets. The categories used in the decennial census

changed frequently, and both householders and enumerators often failed to dis-

tinguish between unwaged housework and waged domestic service. A substan-

tial proportion of those recorded by the census as domestic servants in the census

were related to the head of household.

72

There were similar problems distin-

guishing domestic servants from nurses and those employed in laundry work. It

is also likely that part-time work undertaken by married women was substan-

tially underenumerated.

73

None the less it is possible to use census returns to give

some very general indications of the changing size of the market for domestic

servants. There were around . million domestic servants recorded in the

census. This increased to over million in the last three decades of the nine-

teenth century.

74

The numbers employed in domestic service declined slightly

during the Edwardian period, and more rapidly after the First World War.

However, even as late as . million workers were recorded as domestic ser-

vants, of whom . million were women.

The broad categories of the census obscured wide variations in the nature of

jobs and career patterns. The most common popular image of domestic service

has been of the retinues of servants retained in country houses or large town

houses. Employment ‘below stairs’ in a ‘big house’ was marked by fine distinc-

tions between the various jobs but was generally relatively secure, and for some

could mean a lifetime’s work in service. However, most domestic servants worked

outside of these more formal employment structures. The commonest form of

domestic servant was probably the young unmarried ‘maid of all work’ from a

rural or industrial area living and working single-handedly in a middle-class

The urban labour market

71

See P. Horn, ed., The Rise and Fall of the Victorian Servant (Dublin, ), pp. –.

72

E. Higgs, Domestic Servants and Households in Rochdale (New York, ).

73

E. Roberts, Women’s Work, – (Basingstoke, ), p. .

74

Census returns indicate an absolute decline in the number of servants from , but this is likely

to have been an effect of more careful distinctions being made between paid service and unpaid

domestic labour. See E. Higgs, ‘Domestics servants and households in Victorian England’, Soc.

Hist., (), –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

home.

75

This form of domestic service normally ended on marriage and the for-

mation of an independent household. By contrast other forms of domestic

service such as charring and laundry work were usually restricted to older

married or widowed women.

There were various ways of ‘getting a place’ in service. By the middle of the

nineteenth century annual hiring or so-called ‘Mop’ fairs were falling into dis-

repute, and young women and men seeking positions increasingly used informal

networks of neighbours and family or relied upon the help of local clergy and

gentry. Urban tradesmen often acted as unofficial registry offices for servants and

by the end of the nineteenth century advertising for positions in newspapers

became more common.

76

Many young women worked their way through a

series of positions, taking them away from their immediate areas into service in

cities and towns. There were limited opportunities for domestic service in most

parts of the country, even in working-class districts of British cities where poorly

paid part-time cleaning and washing jobs were to be found. At the very bottom

end of the market, Victorian artisans and shopkeepers could employ domestic

servants taken from workhouses or charitable institutions for as little as £ a year,

about a third of the wages paid to the most junior maids in the large households,

or even in some areas without wages in return for board.

77

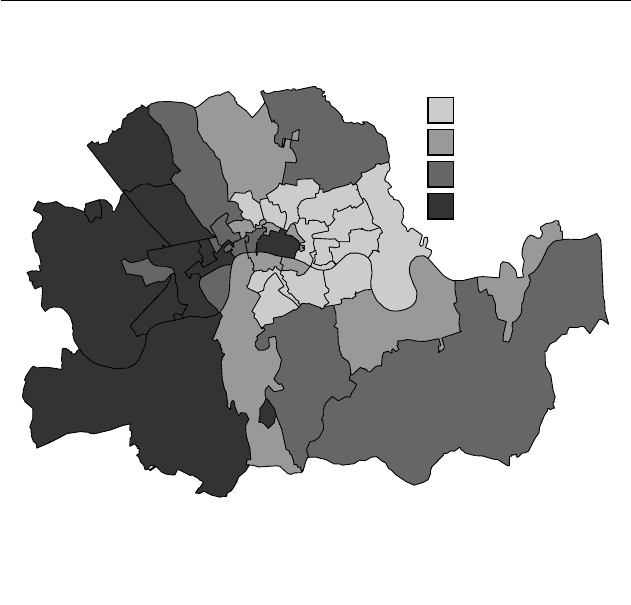

The interactions between domestic service and other labour markets were

important in shaping the urban geography of Britain. Although all major towns

and cities had significant demand for servants, London was by far the most

important single labour market. Within London there was a strikingly polarised

geography of female domestic service, as shown in Map .. The enormous

numbers of female domestic servants in some districts affected the overall gender

balance: in , Kensington Registration District had twice as many women as

men in the age group twenty to twenty-four, and Hampstead three times as

many.

78

Plotting similar information for shows little change, and brings out

the scale of social disparities within London: Hampstead had domestic ser-

vants per thousand households, the highest rate in the country, while Bethnal

Green had thirty-five, the lowest in the country apart from six small Urban

Districts in Lancashire.

79

Domestic service played a significant and underrecognised role in rural– urban

migration, and in-migration between British urban areas. A high proportion of

David Gilbert and Humphrey Southall

75

E. Higgs, ‘Domestic service and household production’, in A.V. John, ed., Unequal Opportunities

(Oxford, ), pp. –.

76

Horn, ed., Rise and Fall, pp. –.

77

F. K. Prochaska, ‘Female philanthropy and domestic service in Victorian England’ Bull. IHR,

(), –.

78

Data from table ‘Ages of males and females’ in the divisional tables in Census of England and Wales

, vol. : Ages, Civil Condition, Occupations, and Birth-Places of the People, PP , parts

and .

79

Data from table (B) ‘Grouped occupations of females aged ten years and upwards’, in Census of

England and Wales , vol. : Occupations and Industries, part , PP , pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

young women entering service came either from agricultural districts or from

areas of heavy industry where women had few employment opportunities.

Women’s entry into domestic service was often a consequence of a lack of alter-

native employment possibilities. In the cotton- and textile-producing districts of

northern England women were likely to choose factory work as an alternative

to domestic service. In these areas domestic service acted as a labour market

which could absorb young women in times of economic distress. Women

factory workers were poorly organised and thus largely excluded from trade

union unemployment relief before the First World War, and payments to women

were restricted under the state insurance schemes. The most familiar story of

migration during the interwar depression concerns the northern unemployed

moving south into the new factories in London and the South-East, but the

established paths into service provided young women entering the labour market

with an alternative southerly escape route from hard times.

Employment prospects for women outside of domestic service were primar-

ily limited by the sex-typing of occupations. A number of factors caused the

long slow decline in employment in domestic service through most of the twen-

tieth century including changes in the nature of middle-class households and

the mechanisation of housework, but the most significant was the growth of

The urban labour market

Under 13.4

13.4 to 19.8

19.8 to 26.6

Over 26.6

Percentage of females

of working age working

as domestic servants:

Map . Domestic servants in London

Source: census (data transcribed and provided by David Allan Gatley).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

alternative employment opportunities for young women. At the end of the nine-

teenth century rural depopulation had more or less drained one of the largest

pools of female labour without relatively attractive alternative employment pros-

pects. The First World War pushed many women into jobs traditionally defined

as male, and the number of women employed in domestic service dropped from

. million in to . million in .

80

The backlash against women

workers in many industries which followed the war forced many women back

into domestic service, but the rise of new kinds of ‘women’s work’ on factory

production lines, in consumer industries and in clerical work continued to erode

the supply of servants. These new occupations were concentrated in the parts of

the country where domestic service was most important.

(vi) -

The expansion of white-collar work, particularly during the twentieth century,

made a very direct and obvious mark on the physical landscape of British towns

and cities. Whole central districts were turned over to office buildings and to

servicing the needs of the new legions of office workers. But the expansion of

white-collar work had other influences on the development of the British urban

system. White-collar work, with the security that came from regular salaried

income, produced new possibilities and expectations for millions of households:

it was a major influence on the growth of suburbia, it introduced new working

roles for women and new forms of gender-segregation in urban labour markets

and it led to new forms of career patterns and spatial movement through the

urban system.

To some extent both the growth and the changing gender relations of office

work can be gauged by census records of the number of clerical workers (see

Table .) In fewer than one worker in a hundred was a clerk, and to all

intents and purposes all clerks were men. A hundred years later, one in ten

workers was employed in clerical work, and a clear majority of clerical workers

were women. However, as with many other forms of work, general census cat-

egories obscure social, organisational and technical changes in the nature of

white-collar work . By the mid-twentieth century what the census enumerated

as clerical work was but part of a larger labour market for white-collar workers.

For example, those classified as managers increased from around per cent of

the workforce in the late Victorian economy to . per cent by , yet man-

agerial work had shifted away from supervision of industrial production towards

the administration of people or products.

81

Similarly, the nature and status of

professional work had broadened. Although the elites of medicine, the law

and the higher echelons of the civil service remained relatively closed and

David Gilbert and Humphrey Southall

80

J. Bourke, Working-Class Cultures in Britain – (London, ), p. .

81

M. Savage et al., Property, Bureaucracy and Culture (London, ), pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

self-recruiting, by the interwar period significant numbers were employed in

lower status professions, notably in school teaching and welfare services.

Mid-Victorian clerks were employed in a variety of organisations. The major-

ity of clerks worked in the ‘counting houses’ of commercial and industrial com-

panies.

82

Offices tended to be small: in Benjamin Orchard estimated that

the average size of commercial offices in Liverpool was just four clerks, and many

smaller firms employed a solitary book-keeper.

83

The largest employers were

local and central government, banks, insurance companies and railway compa-

nies, and it was within these corporate organisations that new white-collar roles

and career structures started to develop. By the late nineteenth century commer-

cial firms were also centralising and expanding, and the labour market for white-

collar work was dividing into two distinct sections. For some clerical workers,

the increasing size and scale of businesses and organisations brought the chance

of a career with considerable prospects for upward mobility. However, many

men in lower grades of clerical work faced increasing competition for their jobs

from foreign and women workers.

Organisational career structures developed earliest in the banking industry.

Unlike many commercial firms apprenticeship as a clerk in a bank usually guar-

anteed a secure post and a foot on the career ladder. Most large or medium-sized

banks had a structure of branches, and a good ratio of managers to ordinary cler-

ical workers. This meant both that there were good prospects for upward mobil-

ity through the organisation, and that geographical mobility and career mobility

were closely linked. The career of William Smalley, first a clerk then manager in

the North and South Wales Bank, was not untypical. After joining the bank as

a clerk in he moved between posts in Mold, Liverpool, Holywell and

Oswestry before being appointed manager in Llanidloes in . He then moved

back to the bank’s head office in Liverpool, and on to another manager’s post at

The urban labour market

82

See D. Lockwood, The Blackcoated Worker, nd edn (Oxford, ); G. Anderson, Victorian Clerks

(Manchester, ).

83

B. G. Orchard, The Clerks of Liverpool (Liverpool, ), p. .

Table . Growth and feminisation of clerical work

–

Clerks as percentage Female clerks as

Year of total labour force percentage of all clerks

. .

..

..

..

Source: D. Lockwood, The Blackcoated Worker, nd edn

(Oxford, ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Rhayader, before finally settling at the Rhyl branch in .

84

During the late

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries amalgamations and takeovers created a

banking industry which was national rather than regional in scale, and which

was increasingly centralised in London, with concomitant consequences for

career paths.

85

Organisational career structures were rather different for managers in manu-

facturing industry. The single firm career was equally important: the Acton

Society Trust’s survey of forty-four of the largest manufacturing compa-

nies in Britain found that per cent of managers had either worked exclusively

in one company, or had joined their present company before the age of twenty-

five.

86

However, this did not imply that managers in manufacturing were as geo-

graphically mobile as their counterparts in financial services. Britain retained

many relatively small family-controlled firms, and larger manufacturing compa-

nies were slow to develop the kind of integrated organisational structures which

were common in the United States. Where large British companies had been

formed through merger, the management structures and practices of the origi-

nal companies were often retained under a small central holding company.

Managers in manufacturing were therefore among the least geographically

mobile of the emerging twentieth-century middle class.

The state’s increasing involvement in health, law and education meant that

organisational career paths became more important for the professions during

the first half of the twentieth century. However, for many professionals career

progression remained one of changing jobs within an occupation rather than

promotion in a single organisation. Professionals were the first major occupa-

tional group to establish career patterns in which occupational advancement

worked through criteria which were not spatially fixed, and where the relation-

ship of the individual to town or region became more or less contingent.

87

The

career paths of many nineteenth-century clerics, lawyers and doctors prefigured

the kind of simultaneous spatial and social mobility associated with the ‘spiral-

ism’ of many mid- and late twentieth-century careers.

88

This is not to say that

the distribution of professionals across the country was either even or random.

Professional networks and formal organisations were usually urban and increas-

ingly based in London. The professions established a pattern of living which pro-

vided a model for the new aspirational middle classes. London and the

South-East was reinforced as the most prestigious region, particular suburbs and

districts of major towns and cities were marked as socially desirable, and the kind

David Gilbert and Humphrey Southall

84

G. L. Anderson, Victorian Clerks (Manchester, ), p. .

85

M. Savage, ‘Career mobility and class formation: British banking workers and the lower middle

classes’, in A. G. Miles and D. Vincent, eds., Building European Society (Manchester, ), p. .

86

Acton Society Trust, Management Succession (London, ), cited in Savage et al., Property,

Bureaucracy and Culture, pp. –.

87

Savage et al., Property, Bureaucracy and Culture, pp. –.

88

W. Watson, ‘Social mobility and social class in industrial societies’, in M. Glucksman and E.

Devons, eds., Closed Systems and Open Minds (Edinburgh, ), pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

of privatised domestic life associated with an un-rooted career became an estab-

lished middle-class norm.

Alongside these developments were other changes in the white-collar labour

market which had quite different implications for social and geographical mobil-

ity. Indeed, it can be argued that the development of the middle-class career

structure, whether organisational or occupational, depended upon the simulta-

neous growth in the number of low-paid and low-status clerical workers, who

were locally based and had very limited career prospects. As early as the s,

English clerks were concerned that they were being undercut by German and

Scottish clerks who ‘swarm to England and France in thousands, accepting duties

at any salary they are offered’.

89

However, the growth of female employment was

a far more lasting and significant change in the white-collar labour market. The

Post Office Savings Bank and the new telegraph services were early employers

of female clerks in the s, followed by larger commercial firms, insurance

firms and the banks. Certain new clerical skills, notably shorthand and typing,

came to be defined as women’s work.

90

The First World War saw a major expan-

sion in the number of women clerks, and unlike in engineering and factory

work, this was a permanent change in the labour market.

In the early expansion of women’s clerical work, women were seen as a direct

challenge to the position of male clerks.

91

However, this effect was concentrated

at the bottom of the clerical labour market, and by the s job opportunities

and career structures for men and women were becoming increasingly

differentiated. In the banks, for example, women were given a special, separate

grade within the organisation, while male clerical work became increasingly

managerial with clear opportunities for promotion and mobility.

92

The lack of

career prospects for women white-collar workers was reinforced by social and in

some occupations legal constraints on work after marriage. In the Civil Service

the marriage bar was removed only as late as , and the ban was actively sup-

ported by many single women workers who saw married women as competition

for their position. This marked gendering of white-collar work had very direct

consequences for the nature of cities. The growth of a relatively privileged male

white-collar salariat was a key influence on the growth of suburbia, particularly

between the wars. A form of domestic life in which male commuting and female

housework became established norms was related to social and cultural expecta-

tions, but also to the very different labour market opportunities for middle-class

married men and women. London was the paramount centre for female clerical

work, and the city saw the development of a new geography of independent

young female households, concentrated in the inner west London suburbs.

The urban labour market

89

C. E. Parsons, Clerks:Their Position and Advancement (London, ), p. .

90

Roberts, Women’s Work, p. .

91

M. Zimmeck, ‘Jobs for the girls: the expansion of clerical work for women –’, in John,

ed., Unequal Opportunities, pp. –.

92

Savage, ‘Career, mobility’, p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

(vii) :

The central concern of this chapter has been how labour markets shaped the lives

of individual people and, indirectly, the form of individual towns: the casual

workers, confined to particular quarters by their dependence on information

networks for finding work; the artisans with their movements from town to

town and their ‘houses of call’ serving as informal labour markets; domestic ser-

vants, so numerous in some parts of cities as to create otherwise inexplicable

demographic structures; the role of employers in building new communities to

house their workers. This conclusion shifts focus to the urban system as a whole

and explores the complex divisions of labour which characterised both nine-

teenth- and twentieth-century Britain.

Traditionally, regional geographers have argued that the Industrial Revolution

meant an end to the distinctive local cultures of pre-industrial times: people no

longer wore characteristic local clothing but cloth from Lancashire and shoes

from Northamptonshire. Similarly, traditional housing styles using local materi-

als were replaced by standard styles using bricks from Bedfordshire and slates

from North Wales. In , John Langton argued that the Industrial Revolution

had actually increased regional diversity, pointing out that precisely this homo-

genisation of consumption required specialisation in production, in how people

and communities earned their living: Lancashire became the ‘cotton districts’,

Llanberis and Blaenau Ffestiniog almost synonymous with slate.

93

This argument can easily be taken too far: while mining and weaving were

highly localised, artisans tended to be found in every town, and as we have seen

were highly mobile between them; while a town might be unable to change its

specialisation, people could and did make large career changes; and London was

always a vast exception. Map . draws on two census reports, eighty years

apart, which provide comparable occupational statistics for individual towns.

94

The upper pair of maps classify the urban workforce of each county into three

broad categories: those where service sector employment was greater than all in

David Gilbert and Humphrey Southall

93

J. Langton, ‘The Industrial Revolution and the regional geography of England’, Transactions of the

Institute of British Geographers, (), –.

94

Such an analysis, completely excluding rural populations, is possible for relatively few censuses.

The census tabulated occupations by county and selected towns, sometimes using boroughs

and sometimes ad hoc assemblies of parishes, whereas later nineteenth-century censuses used

Registration Districts which combined towns with their hinterlands. was the first census

systematically to gather occupational data and, because it reported them in almost raw form, it is

possible here to assign them to the occupational classification. The census was the first

to report occupations for all individual local government districts, so here the county figures sum-

marise those for all individual County and Municipal Boroughs, Urban Districts, and for Scotland

Cities and Large Burghs. The data for England and Wales consequently include figures for

smaller towns relative to Scotland, and to . Here, and in Maps . and ., the small number

of Scottish towns in the data necessitates merging counties into five broader regions.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

manufacturing; those others where the old staple industries employed more than

light manufacturing; and those where light industrial employment exceeded the

staple industries.

95

The lower pair of maps use the same data to measure the degree

of occupational specialisation in each locality: towns with low index values had

a broadly based employment structure, while high values indicate a reliance on

one or two sectors.

96

Urban specialisations in were much as we would expect, showing a clear

polarisation between the manufacturing districts of the North and of South

Wales, and the remainder of the country dominated by the service sector; only

a relatively small area in the South-East Midlands was dominated by light indus-

try.

97

The map differs significantly, revealing a pre-railway and partially pre-

factory occupational geography: most of the heavy industry of the North-East

of England had still to develop, while much of the textile industry was still based

in small towns away from the coalfields, in Wiltshire and North Wales. However,

the domination of the South-East by services was already established.

We tend to assume that towns specialised by product, and hence in terms of

manufacturing, but the lower pair of maps and especially that for partly

reflect specialisation within services. Berkshire was the second most specialised

county based entirely on figures for Reading, half the workforce being

classed as ‘Commercial, financial and insurance’. While Wiltshire’s specialisation

was primarily into textiles, occupying per cent of workers in Trowbridge,

towns in Berkshire and Somerset were again specialised into services: retailing

in Reading, and the various luxury trades of Bath, where per cent of workers

were in domestic service. Cheltenham and Brighton had the same percentage,

while per cent of all workers in Leamington Spa were in domestic service.

Manufacturing specialisations also emerge, such as the Staffordshire Potteries

with per cent of Burslem’s workers, per cent of Stoke’s and per cent of

Hanley’s in the sector: no other town had over per cent. The two towns most

dominated by mining were Aberystruth ( per cent) and Bedwellty ( per

cent), both in Monmouthshire. Lancashire was not among the most specialised

counties because of the diverse economies of Liverpool and Manchester, but

The urban labour market

95

This classification was developed by Eilidh Garrett and Alice Reid of the ESRC Cambridge Group.

Of the thirty-two available categories, categories I and II are grouped as agricultural (defined as

dominant in in three counties where the only data concern a single small town: Dolgellau,

New Radnor and Buckingham); III (mining), V (brick making), VII (most metal workers) and XII

(textiles) as ‘Staple’; VI, VIII, IX, X, XI, XIII through XX, XXIX and XXX as ‘Light’; XXI

through XXVIII as ‘Services’; and XXXI and XXXII as discarded residual categories.

96

The method is taken from R. C. Tress, ‘Unemployment and the diversification of industry’,

Manchester School, (), –; Tress himself was able to compute his index for only a small

number of towns. Our county index values are averages of index values computed for individual

towns, weighted by total numbers employed, so a county consisting of towns with diverse but

extreme specialisms will have a high index value.

97

The growth of services pre- is emphasised by C. H. Lee, ‘Regional growth and structural

change in Victorian Britain’, Ec.HR, nd series, (), –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008