Duiker William J., Spielvogel Jackson J. The Essential World History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

In France, the confusion that ensued after the col-

lapse of Louis Napoleon’s Second Empire finally ended in

1875 when an improvised constitution established a re-

publican form of government---the Third Republic---that

lasted sixty-five years. France’s parliamentary system was

weak, however, because the existence of a dozen political

parties forced the premier (or prime minister) to depend

on a coalition of parties to stay in power. The Third

Republic was notorious for its changes of government.

Nevertheless, by 1914, the French Third Republic com-

manded the loyalty of most French people.

Central and Eastern Europe:

Persistence of the Old Order

The constitution of the new imperial Germany begun by

Chancellor Otto von Bismarck in 1871 provided for a

bicameral legislature. The lower house of the German

parliament, the Reichstag, was elected by universal male

suffrage, but it did not have ministerial responsibility.

Ministers of government, among whom the most im-

portant was the chancellor, were responsible to the em-

peror, not the parliament. The emperor also commanded

the armed forces and controlled foreign policy and the

government.

During the reign of Emperor William II (1888--

1918), the new imperial Germany begun by Bismarck

continued as an ‘‘authoritarian, conservative, military-

bureaucratic power state.’’ By the end of William’s reign,

Germany had become the strongest military and indus-

trial power on the Continent, but the rapid change had

also helped produce a society torn between moderniza-

tion and traditionalism. With the expansion of industry

and cities came demands for true democracy. Conserva-

tive forces, especially the landowning nobility and in-

dustrialists, two of the powerful ruling groups in imperial

Germany, tried to block the movement for democracy by

supporting William II’s activist foreign policy. Expansion

abroad, they believed, would divert people’s attention

from the yearning for democracy at home.

After the creation of the dual monarchy of Austria-

Hungary in 1867, the Austrian part received a constitu-

tion that theoretically established a parliamentary system.

In practice, however, Emperor Francis Joseph (1848--

1916) largely ignored parliament, ruling by decree when

parliament was not in session. The problem of the various

nationalities also remained troublesome. The German

minority that governed Austria felt increasingly threat-

ened by the Czechs, Poles, and other Slavic groups within

the empire. Their agitation in the parliament for auton-

omy led prime ministers after 1900 to ignore the parlia-

ment and rely increasingly on imperial decrees to govern.

In Russia, the assassination of Alexander II in 1881

convinced his son and successor, Alexander III (1881--

1894), that reform had been a mistake, and he lost no

time in persecuting both reformers and revolutionaries.

When Alexander III died, his weak son and successor,

Nicholas II (1894--1917), began his rule with his father’s

conviction that the absolute power of the tsars should be

preserved: ‘‘I shall maintain the principle of autocracy just

as firmly and unflinchingly as did my unforgettable

father.’’

6

But conditions were changing.

Industrialization progressed rapidly in Russia after

1890, and with industrialization came factories, an in-

dustrial working class, and the development of socialist

parties, including the Marxist Social Democratic Party

and the Social Revolutionaries. Although repression

forced both parties to go underground, the growing op-

position to the tsarist regime finally exploded into revo-

lution in 1905.

The defeat of the Russians by the Japanese in 1904--

1905 encouraged antigovernment groups to rebel against

the tsarist regime. Nicholas II granted civil liberties and

created a legislative assembly, the Duma, elected directly

by a broad franchise. But real constitutional monarchy

proved short-lived. By 1907, the tsar had curtailed the

power of the Duma and relied again on the army and

bureaucracy to rule Russia.

International Rivalries and the Winds of War

Bismarck had realized in 1871 that the emergence of a

unified Germany as the most powerful state on the

CHRONOLOGY

The National State, 1870--1914

Great Britain

Formation of Labour Party 1900

National Insurance Act 1911

France

Republican constitution (Third Republic) 1875

Germany

Bismarck as chancellor 1871--1890

Emperor William II 1888--1918

Austria-Hungary

Emperor Francis Joseph 1848--1916

Russia

Tsar Alexander III 1881--1894

Tsar Nicholas II 1894--1917

Russo-Japanese War 1904--1905

Revolution 1905

484 CHAPTER 19 THE BEGINNINGS OF MODERNIZATION

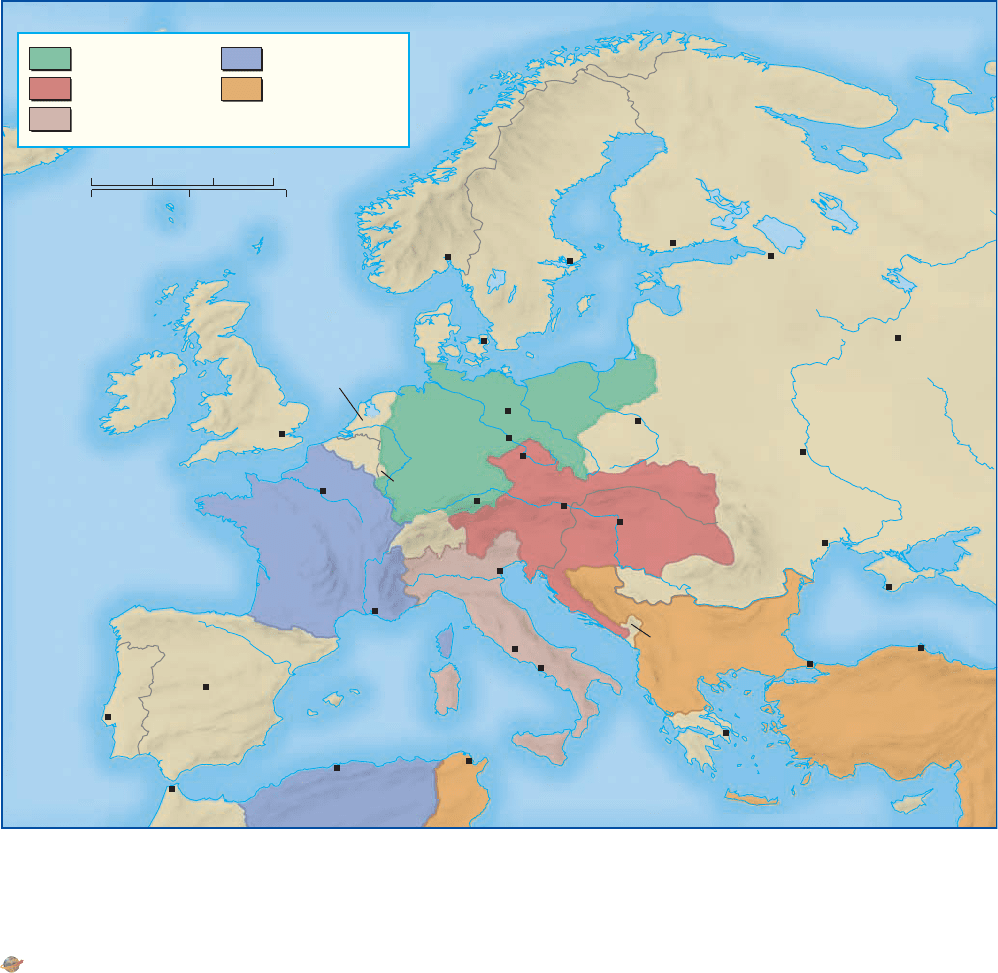

Continent (see Map 19.3) had upset the balance of power

established at Vienna in 1815. Fearful of a possible anti-

German alliance between France and Russia, and possibly

even Austria, Bismarck made a defensive alliance with

Austria in 1879. Three years later, this German-Austrian

alliance was enlarged w ith the entrance of Italy, angry

with the French over conflicting colonial ambitions in

North Africa. The Triple Alliance of 1882---Germany,

Austria-Hungary, and Italy---committed the three powers

to a defensive alliance against France. At the same time,

Bismarck maintained a separate treaty with Russia.

When Emperor William II cashiered Bismarck in

1890 and took over direction of Germany’s foreign policy,

he embarked on an activist foreign policy dedicated to

enhancing German power by finding, as he put it, Ger-

many’s rightful ‘‘place in the sun.’’ One of his changes in

Bismarck’s foreign policy was to drop the treaty with

Russia, which he viewed as being at odds with Germany’s

Cyprus

Crete

Sicily

Sardinia

Corsica

Black Sea

Atlantic

Ocean

Arctic Ocean

FINLAND

GREECE

MOROCCO

ALGERIA

TUNISIA

ITALY

SPAIN

PORTUGAL

FRANCE

GREAT

BRITAIN

BELGIUM

NETHERLANDS

LUXEMBOURG

SWITZERLAND

AUSTRIA

HUNGARY

ROMANIA

SERBIA

BULGARIA

BOSNIA

HERZ.

MONTENEGRO

ALBANIA

M

A

C

E

D

O

N

I

A

CROATIA -

SLOVENIA

B

E

S

S

A

R

A

B

I

A

CRIMEA

RUSSIAN

EMPIRE

OTTOMAN EMPIRE

Athens

Naples

Rome

Venice

Tunis

Algiers

Tangier

Lisbon

Madrid

Marseilles

Paris

Munich

London

Saint Petersburg

Moscow

Kiev

Odessa

Sinope

Constantinople

Budapest

Sevastopol

R

h

i

n

e

R

.

V

o

l

g

a

R

.

P

o

R

.

E

b

r

o

R

.

A

l

p

s

T

a

u

r

u

s

M

t

s

.

B

a

l

e

a

r

i

c

I

s

l

a

n

d

s

P

y

r

e

n

e

e

s

Mediterranean Sea

North

Sea

Baltic

Sea

POLAND

DENMARK

NORWAY

and

SWEDEN

AUSTRIA-

HUNGARY

Kristiania

Stockholm

Helsingfors

Prague

Warsaw

Dresden

Berlin

Copenhagen

E

l

b

e

R

.

Vienna

O

d

e

r

R

.

D

a

n

u

b

e

R

.

German Empire

Austria-Hungary

Italy

France

Ottoman Empire

0 250 500 Miles

0 250 500 750 Kilometers

MAP 19.3 Europe in 1871. German unification in 1871 upset the balance of power

established at Vienna in 1815 and eventually led to a realignm ent of European alliances.

By 1907, Europe was divided into two opposing camps: the Triple Entente of Great Britain,

Russia, and France and the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy.

Q

How was Germany affected b y the formation of the Triple Entente?

View an animated version of this map or related maps at www .c engage.com/ history/

duikspiel/essentialworld6e

THE EUROPEAN STATE, 1871--1914 485

alliance with Austria. The ending of the alliance brought

France and Russia together, and in 1894, the two powers

concluded a military alliance. During the next ten years,

German policies abroad caused the British to draw closer

to France. By 1907, an alliance of Great Britain, France,

and Russia---known as the Triple Entente---stood opposed

to the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and

Italy. Europe became divided into two opposing camps

that became more and more inflexible and unwilling to

compromise. A series of crises in the Balkans between

1908 and 1913 set the stage for World War I.

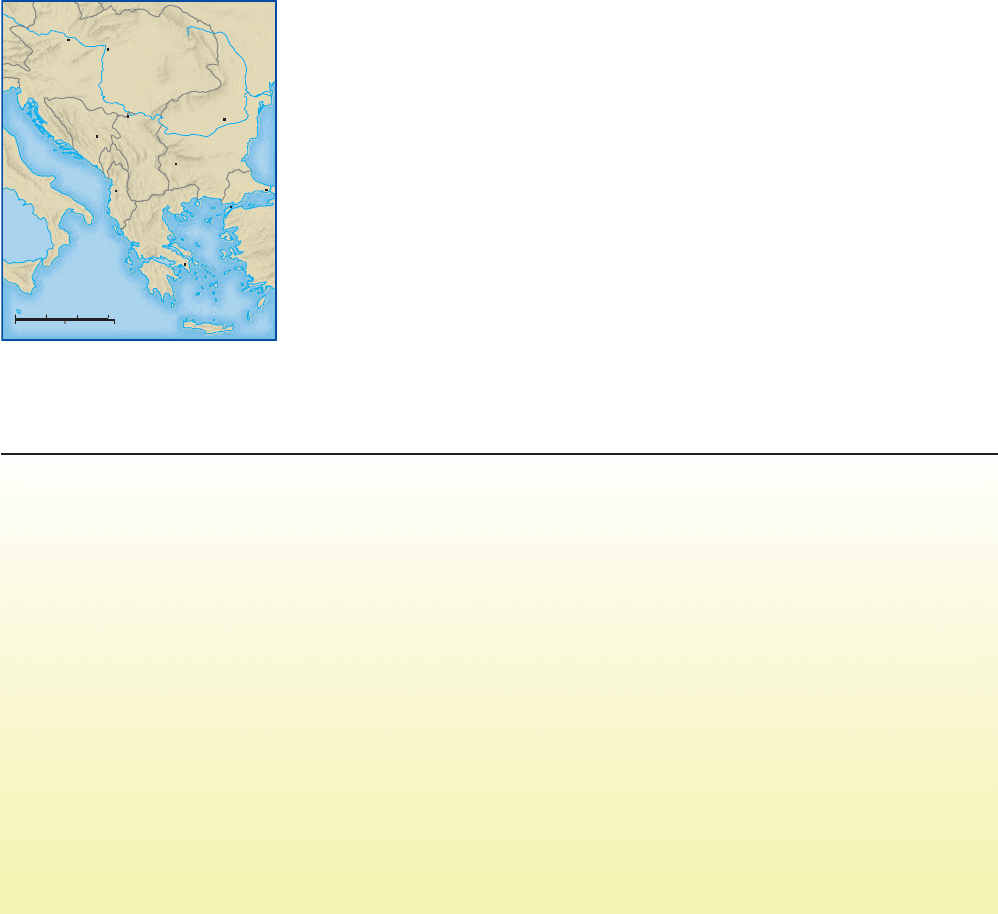

Crisis in the Balkans Over the course of the nine-

teenth century, the Balkan provi nces of the Ottoman

Empire had gradu-

ally gained their

freedom, although

the rivalry in the re-

gion between Austria

and Russia compli-

cate d the process. By

1878, Greece, Serbia,

and Romania had

become independent

states. Although freed

from Ottoman rule,

Montenegro was

placed under an

Austrian protector-

ate, while Bulgaria

achieved autonomous status under Russian protection.

Bosnia and Herzegovina were placed under Austrian

protection; Austria could occupy but not annex them.

Nevertheless, in 1908, Austria did annex the two

Slavic-speaking territories. Serbia was outraged because

the annexation dashed the Serbs’ hopes of creating a

large Serbian kingdom that would unite most of the

southern Slavs. The Russian s, as protectors of their

fellow Slavs, suppor ted the Ser bs and opposed the

Austrian action. Backed by the Russians, the Serbs

prepared for war against Austria. At this point, William

II inter vened and demanded that the Russians accept

Austria’s annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina or face

war with Germany. Weakened from their defeat in the

Russo-Japanese War in 1904--1905, the Russians backed

down but vowed revenge. Two wars between the Balkan

states in 1912--1913 further embittered the inhabitants

of the region and generated more tensions among the

gre at powers.

Serbia’s desire to create a large Serbian kingdom

remained unfulfilled. In their frustration, Serbian na-

tionalists blamed the Austrians. Austria-Hungary was

convinced that Serbia was a mortal threat to its empire

and must at some point be crushed. As Serbia’s chief

supporters, the Russians were determined not to back

down again in the event of a confrontation with Austria or

Germany in the Balkans. The allies of Austria-Hungary

and Russia were also determined to be more supportive of

their respective allies in another crisis. By the beginning of

1914, two armed camps viewed each other with suspicion.

D

a

n

u

b

e

R

.

M

e

d

i

t

e

r

r

a

n

e

a

n

S

e

a

A

d

r

i

a

t

i

c

S

e

a

Black

Sea

P

r

u

t

h

R

.

GERMANY

ITALY

GREECE

SERBIA

ALBANIA

MONTENEGRO

BULGARIA

ROMANIA

RUSSIA

AUSTRIA-HUNGARY

BOSNIA AND

HERZEGOVINA

O

T

T

O

M

A

N

E

M

P

I

R

E

Tirana

Vienna

Belgrade

Sarajevo

Budapest

Athens

Constantinople

Bucharest

Sofia

Gallipoli

C

a

r

p

a

t

h

i

a

n

M

t

s

.

Sicily

Crete

MACEDONIA

TRANSYLVANIA

0 100 200 Miles

0 100 200 300 Kilometers

The Balkans in 1913

CONCLUSION

THE FORCES UNLEASHED between 1800 and 1870 by

two revolut ions---the French Revolution and the In dustrial

Revolution---led to Wester n global dominance by the end of the

nineteent h century. The First and Secon d Industrial Revolu tions

seemed to prove to Europeans the underlying a ssumption of the

Scientific Revolution of the seventeenth century---that human

beings were capable of dominating nature. By rationally

manipulating the material environment for human benefit, people

could achieve new levels of material prosperity and produce

machines hitherto not dreamed of in their wildest imaginings.

Some of these new machines included weapons of war that

enabled the Western world to devastate and dominate non-

Western civilizations.

In 1815, a conservative order had been reestablished

throughout Europe, but the revolutionary waves in Europe in the

first half of the nineteenth centur y made it clear that the ideologies

of liberalism and nati onalism, unl eashed by the French Revolution

and now reinforced by the spread of industrialization, were still

alive and active. Between 1850 and 1871 , the national state became

the focus of people’s loyalty. Wars, both foreign and civil, were

fought to create unified nation-states, and both wars and changing

political alignments served as catalysts for domestic reforms that

made the nation-state the center of attention. Liberal nationalists

had believed that unified nation-states would preserve individual

rights and lead to a greater community of peoples. But the new

nationalism of the late nineteenth century, loud and patriotic, did

not unify peoples but div ided them instead as the new national

states became embroiled in bitter competition after 1871.

Between 1871 and 1914, the national state began to expand

its functions beyond all previous limits. Fearful of the growth of

socialism and trade unions, governments attempted to appease

the working mas ses by adopting such social insurance measures

as compensation for accidents, illness, and old age. These social

welfare m easures provided o nly limited ben efits before 1914, but

they signaled a new direction for state action to benefit all

citizens.

486 CHAPTER 19 THE BEGINNINGS OF MODERNIZATION

SUGGESTED READING

The Industrial Revolution and Its Impact Still a good

introduction to the Industrial Revolution is the well-written work by

D. Landes, The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and

Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the

Present (Cambridge, 1969). Also valuable is J. Horn, The Industrial

Revolution (Westport, Conn., 2007). For a broader perspective, see

P. Stearns, The Industrial Revolution in World History (Boulder,

Colo., 1993). On the role of the British, see K. Morgan, The Birth

of Industrial Britain: Social Change, 1750--1850 (New York, 2004).

On the social impact of the Industrial Revolution, see P. Pilbeam,

The Middle Classes in Europe, 1789--1914 (Basingstoke, England,

1990), and J. G. Williamson, Coping with City Growth During the

British Industrial Revolution (Cambridge, 2002).

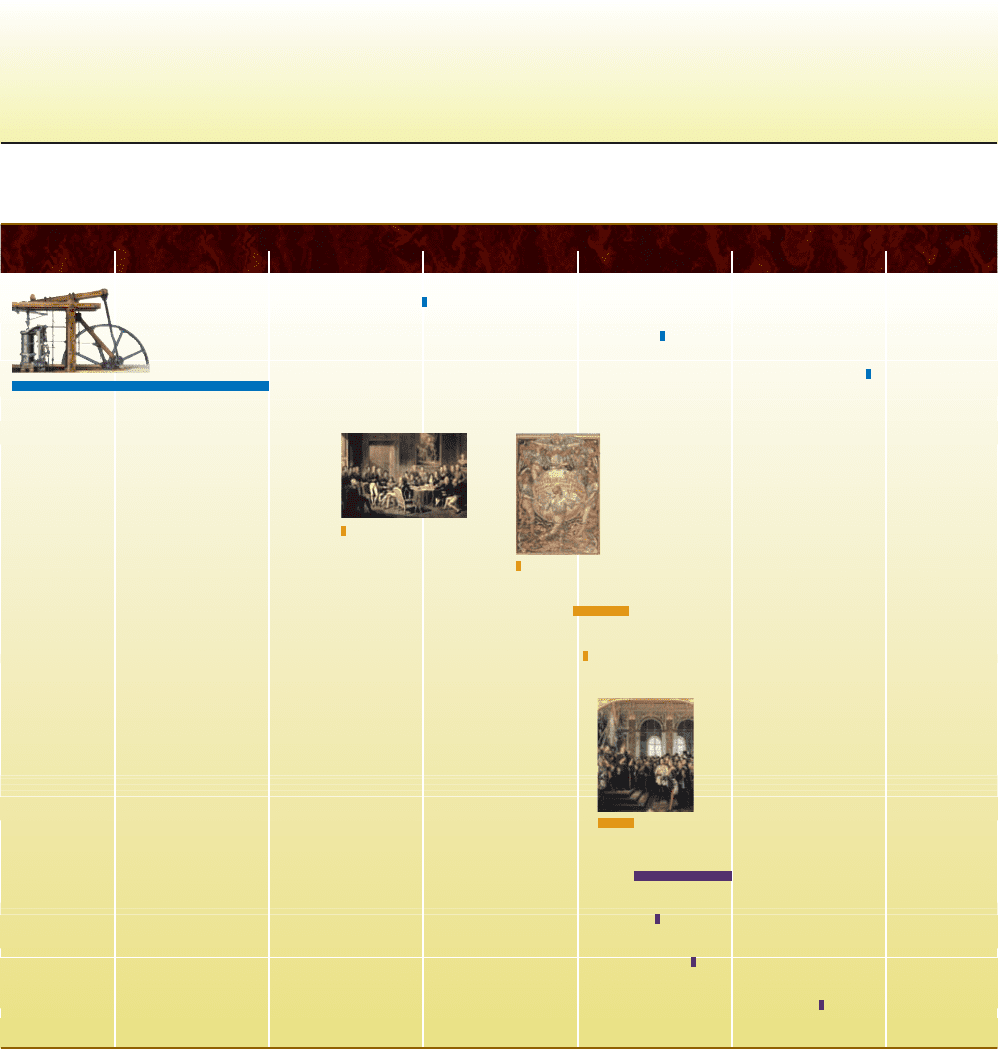

TIMELINE

1770

1800 1830 1860 1890 1920

Beginning of the Industrial Revolution in Britain

Stephenson's Rocket

Bell invents the telephone

Mass production of

Ford's Model T

Revolutions of 1848

Unification of Italy

Emancipation of Russian serfs

Unification of Germany

Bismarck as chancellor of Germany

Beginning of Third Republic in France

Triple Alliance

Triple Entente

Congress of Vienna

This extension of state functions took place in an atmosphere

of increased national loyalty. After 1871, nation-states increasingly

sought to solidify the social order and win the active loyalty and

support of their citizens by deliberately cultivating national feelings.

Yet this policy contained potentially great dangers. Nations had

discovered once again that imperialistic adventures and military

successes could arouse nationalistic passions and smother domestic

political unrest. But they also found---belatedly in 1914---that

nationalistic feelings could also lead to intense international

rivalries that made war almost inevitable.

CONCLUSION 487

The Growth of Industrial Prosperity The Second Industrial

Revolution is well covered in D. Landes, The Unbound Prometheus.

For a fundamental survey of European industrialization, see A. S.

Milward and S. B. Saul, The Development of the Economies of

Continental Europe, 1850--1914 (Cambridge, Mass., 1977). On

Marx, the standard work is D. McLellan, Karl Marx: His Life and

Thought, 4th ed. (New York, 2006). See also F. Wheen, Karl Marx:

A Life (New York, 2001).

The Growth of Nationalism, 1814--1848 For a good survey

of the nineteenth century, see R. Gildea, Barricades and Borders:

Europe, 1800--1914, 3rd ed. (Oxford, 2003). Also valuable is

T. C. W. Blanning, ed., Nineteenth Century: Europe, 1789--1914

(Oxford, 2000). For a survey of the period 1814--1848, see

M. Broers, Europe After Napoleon: Revolution, Reaction, and

Romanticism, 1814--1848 (New York, 1996), and M. Lyons,

Postrevolutionary Europe, 1815--1856 (New York, 2006). The best

introduction to the revolutions of 1848 is J. Sperber, The European

Revolutions, 1848--1851, 2nd ed. (New York, 2005).

National Unification and the National State, 1848--1871 The

unification of Italy can be examined in B. Derek and E. F. Biagini,

The Risorgimento and the Unification of Italy, 2nd ed. (London,

2002), and H. Hearder, Cavour (New York, 1994). The unification

of Germany can be pursued first in two good biographies of

Bismarck, E. Crankshaw, Bismarck (New York, 1981), and

E. Feuchtwanger, Bismarck (London, 2002). For a good

introduction to the French Second Empire, see J. F. McMillan,

Napoleon III (New York, 1991). On the Austrian Empire, see

R. Okey, The Habsburg Monarchy (New York, 2001). Imperial

Russia is covered in T. Chapman, Imperial Russia, 1801--1905

(London, 2001). On Victorian Britain, see W. L. Arnstein,

Queen Victoria (New York, 2005), and I. Machlin, Disraeli

(London, 1995).

The European State, 1871--1914 On Britain, see D. Read,

The Age of Urban Democracy: England, 1868--1914 (New York,

1994). For a detailed examination of French history from 1871 to

1914, see J.-M. Mayeur and M. Reberioux, The Third Republic

from Its Origins to the Great War, 1871--1914 (Cambridge, 1984).

On Germany, see W. J. Mommsen, Imperial Germany, 1867--1918

(New York, 1995), and E. Feuchtwanger, Imperial Germany, 1850--

1918 (London, 2001). On aspects of Russian history, see H. Rogger,

Russia in the Age of Modernization and Revolution, 1881--1917

(London, 1983), and A. Ascher, Revolution of 1905: A Short

History (Stanford, Calif., 2004).

Visit the website for The Essential World History to access study

aids such as Flashcards, Critical Thinking Exercises, and

Chapter Quizzes:

www.cengage.com/history/duikspiel/essentialworld6e

488 CHAPTER 19 THE BEGINNINGS OF MODERNIZATION

489

CHAPTER 20

THE AMERICAS AND SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE WEST

CHAPTER OUTLINE

AND FOCUS QUESTIONS

Latin America in the Nineteenth and Early

Twentieth Centuries

Q

What role did liberalism and nationalism play in Latin

America between 1800 and 1870? What were the major

economic, social, and political trends in Latin America

in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries?

The North American Neighbors:

The United States and Canada

Q

What role did nationalism and liberalism play in the

United States and Canada between 1800 and 1870? What

economic, social, and political trends were evident in the

United States and Canada between 1870 and 1914?

The Emergence of Mass Society

Q

What is meant by the term mass society, and what were

its main characteristics?

Cultural Life: Romanticism and Realism

in the Western World

Q

What were the main characteristics of Romanticism and

Realism?

Toward the Modern Consciousness:

Intellectual and Cultural Developments

Q

What intellectual and cultural developments in the late

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries ‘‘opened the

way to a modern consciousness,’’ and how did this

consciousness differ from earlier worldviews?

CRITICAL THINKING

Q

In what ways were the intellectual and cultural

developments in the Western world between 1800 and

1914 related to the economic, social, and political

developments?

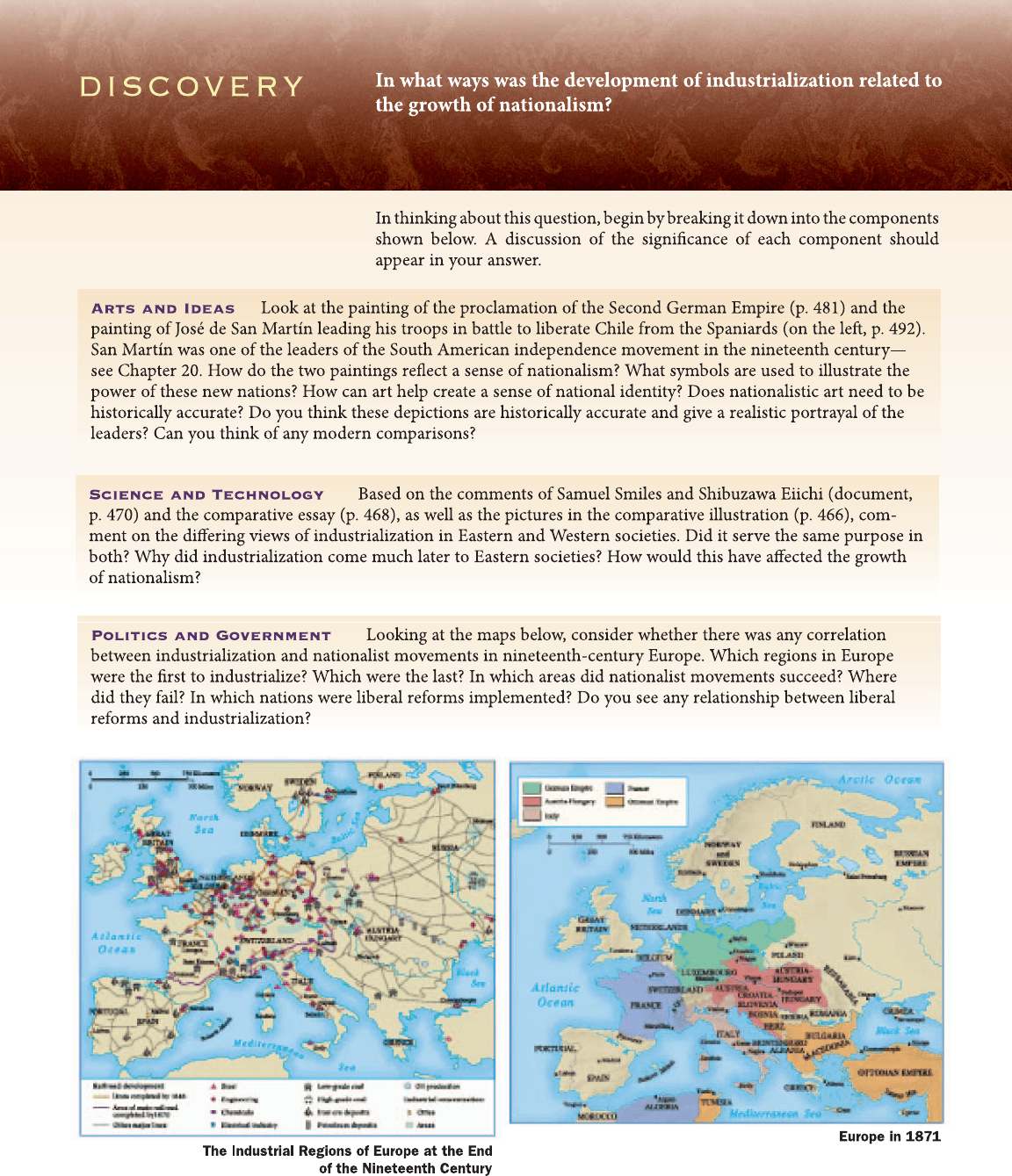

A portrait of Toussaint L’Ouverture, leader of the Haitian

independence movement

c

North Wind Picture Archives

490

NATIONALISM---one of the major forces for change in Europe in

the nineteenth century---also affected Latin America as the colonial

peoples there overthrew their Spanish and Port uguese masters and

began the process of creating new national states. An unusual revo-

lution in Haiti preceded the main independence movements. Pierre

Dominique Toussaint L’Ouverture, the grandson of an African king,

was born a slave in Saint-Domingue---the western third of the island

of Hispaniola, a French sugar colony---in 1746. Educated by his god-

father, Toussaint was able to amass a small private fortune through

his own talents and the generosity of his French master. When black

slaves in Saint-Domingue, inspired by news of the French Revolu-

tion, revolted in 1791, Toussaint became their leader. For years,

Toussaint and his ragtag army struck at the French. By 1801, after

his army had come to control Saint-Domingue, Toussaint assumed

the role of ruler and issued a constitution that freed all slaves.

But Napoleon Bonaparte refused to accept Toussaint’s control

of France’s richest colony and sent a French army of 23,000 men

under General Leclerc, his brother-in-law, to crush the rebellion.

Although yellow fever took its toll on the French, the superior size

and weapons of their army enabled them to gain the upper hand.

Toussaint was tricked into surrendering in 1802 with Leclerc’s

Latin America in the Nineteenth

and Early Twentieth Centuries

Q

Focus Questions: What role did liberalism and

nationalism play in Latin Ameri ca between 1800 and

1870? What were the major economic, social, and

political trends in Latin America in the late nineteenth

and early twentieth centuries?

The Spanish and Portuguese colonial empires in Latin

America had been integrated into the traditional monar-

chical structure of Europe for centuries. When that

structure was challenged, first by the ideas of the

Enlightenment and then by the upheavals of the Napo-

leonic era, Latin America encountered the possibility of

change. How it responded to that possibility, however, was

determined in part by conditions unique to the region.

The Wars for Independence

By the end of the eighteenth century, the ideas of the

Enlightenment and the new political ideals stemming

from the successful revolution in North America were

beginning to influence the creole elites (descendants of

Europeans who became permanent inhabitants of Latin

America). The principles of the equality of all people in

the eyes of the law, free trade, and a free press proved very

attractive. Sons of creoles, such as Simo

´

n Bolı

´

var and Jos

e

de San Martı

´

n, who became leaders of the independence

movement, even went to European universities, where

they imbibed the ideas of the Enlightenment.

Nationalistic Revolts in Latin America The creole

elites soon began to use their new ideas to denounce the

rule of the Iberian monarchs and the peninsulars

(Spanish and Portuguese officials who resided in Latin

America for political and economic gain). As Bolı

´

var said

in 1815, ‘‘It would be easier to have the two continents

meet than to reconcile the spirits of Spain and America.’’

1

When Napoleon Bonaparte toppled the monarchies of

Spain and Portugal, the authority of the Spaniards and

Portuguese in their colonial empires was weakened, and

between 1807 and 1825, a series of revolts enabled most

of Latin America to become independent.

The first revolt was actually a successful slave rebel-

lion. As we have seen, Toussaint L’Ouverture (1746--1803)

led a revolt of more than 100,000 black slaves and seized

control of all of Hispaniola. On January 1, 1804, the

western part of the island, now called Haiti, announced

its freedom and became the first independent postcolo-

nial state in Latin America.

Beginning in 1810, Mexico, too, experienced a revolt,

fueled initially by the desire of the creole elites to over-

throw the rule of the peninsulars. The first real hero of

Mexican independence was Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, a

parish priest in a small village about 100 miles from

Mexico City. Hidalgo had studied the French Revolution

and roused the local Indians and mestizos, many of

whom were suffering from a major famine, to free

themselves from the Spanish. On September 16, 1810, a

crowd of Indians and mestizos, armed with clubs, ma-

chetes, and a few guns, quickly formed a mob army to

attack the Spaniards, shouting, ‘‘Long live independence

and death to the Spaniards.’’ But Hidalgo was not a good

organizer, and his forces were soon crushed. A military

court sentenced Hidalgo to death, but his memory lived

on. In fact, September 16, the first day of the uprising, is

celebrated as Mexico’s Independence Day.

The participation of Indians and mestizos in

Mexico’s revolt against Spanish control frightened both

creoles and peninsulars. Fearful of the masses, they co-

operated in defeating the popular revolutionary forces.

The elites---both creoles and peninsulars---then decided to

overthrow Spanish rule as a way of preserving their own

power. They selected a creole military leader, Augustı

´

nde

Iturbide, as their leader and the first emperor of Mexico

in 1821. The new government fostered neither political

nor economic changes, and it soon became apparent that

Mexican independence had benefited primarily the creole

elites.

LATIN AME RICA IN THE NINETEENTH AND EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURIES 491

promise: ‘‘You will not find a more sincere friend than myself.’’ What

a friend! Toussaint was arrested, put in chains, and shipped to

France, where he died a year later in a dungeon. The western part of

Hispaniola, now called Haiti, however, became the first independent

state in Latin America when Toussaint’s lieutenants drove out the

French forces in 1804. Haiti was only one of a number of places in

the Americas where new nations were formed during the nineteenth

century. Indeed, nation building was prominent in North America as

the United States and Canada expanded.

As national states in both the Western Hemisphere and Europe

were evolving in the nineteenth century, significant changes were oc-

curring in society and culture. The rapid economic changes of the

nineteenth century led to the emergence of mass society in the West-

ern world, which meant improvements for the lower classes, who

benefited from the extension of voting rights, a better standard of

living, and universal education. The coming of mass society also cre-

ated new roles for the governments of nation-states, which now fos-

tered national loyalty, created mass armies by conscription, and took

more responsibility for public health and housing measures in their

cities. Cultural and intellectual changes paralleled these social devel-

opments, and after 1870, Western philosophers, writers, and artists

began exploring modern cultural expressions that questioned tradi-

tional ideas and increasingly provoked a crisis of confidence.

Independence movements elsewhere in Latin Amer-

ica were likewise the work of elites---primarily creoles---

who overthrew Spanish rule and set up new governments

that they could dominate. Jos

e de San Martı

´

n (1778--

1850) of Argentina and Simo

´

n Bolı

´

var (1783--1830) of

Venezuela, leaders of the independence movement, were

both members of the creole elite, and both were hailed as

the liberators of South America.

The Efforts of Bolı

´

var and San Martı

´

n Simo

´

nBolı

´

var

has long been regarded as the George Washington of

Latin America. Born into a wealthy Venezuelan family, he

was introduced as a young man to the ideas of the En-

lightenment. While in Rome in 1805 to witness the cor-

onation of Napoleon as king of Italy, he committed

himself to free his people from Spanish control. He

vowed, ‘‘I swear before the God of my fathers, by my

fathers themselves, by my honor and by my country, that

my arm shall not rest nor my mind be at peace until I

have broken the chains that bind me by the will and

power of Spain.’’

2

When he returned to South America,

Bolı

´

var began to lead the bitter struggle for independence

in Venezuela as well as other parts of northern South

America. Although he was acclaimed as the ‘‘liberator’’ of

Venezuela in 1813 by the people, it was not until 1821

that he definitively defeated Spanish forces there. He went

on to liberate Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. Already in

1819, he had become president of Venezuela, at the time

part of a federation that included Colombia and Ecuador.

Bolı

´

var was well aware of the difficulties in establishing

stable republican governments in Latin America (see the

box on p. 493).

While Bolı

´

var was busy liberating northern South

America from the Spanish, Jos

e de San Martı

´

nwascon-

centrating his efforts on the southern part of the continent.

Son of a Spanish army officer in Argentina, San Martı

´

n

himself went to Spain and pursued a military career in the

Spanish army. In 1811, after serving twenty-two years, he

learned of the liberation movement in his native Argentina,

abandoned his military career in Spain, and returned to his

homeland in Mar ch 1812. Argentina had already been

freed from Spanish control, but San Martı

´

n believed that

the Spaniards must be removed from all of South America

if any nation was to be free. In January 1817, he led his

c

The Art Archive/Museo Nacional de Historia, Lima, Peru/Gianni Dagli Orti

c

Superstock

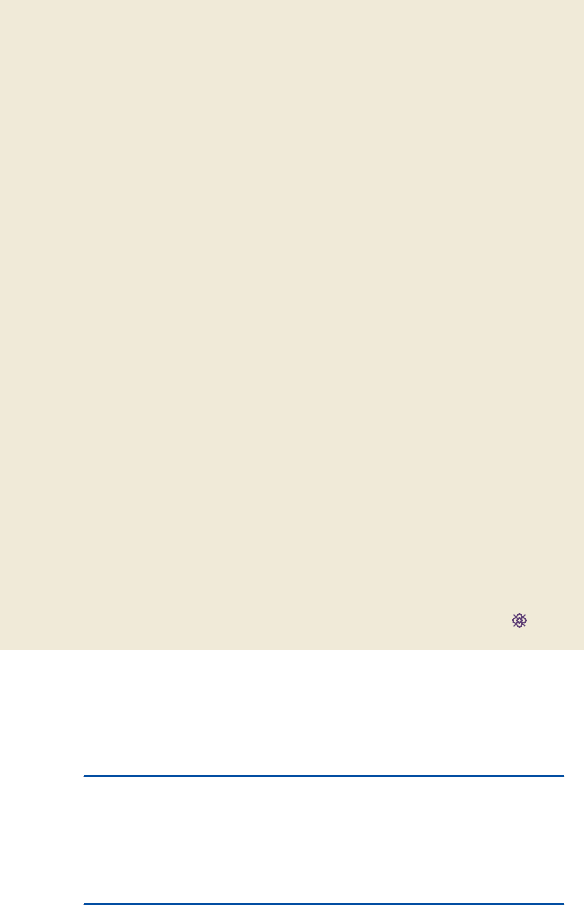

The Liberators of South America. Jos

e de San Martı

´

n and Simo

´

n Bolı

´

var are hailed as the leaders

of the South American independence movement. In the painting on the left, by Theodore G

ericault, a French

Romantic painter, San Martı

´

n is shown leading his troops at the Battle of Chacabuco in Chile in 1817. The

painting on the right shows Bolı

´

var leading his troops across the Andes in 1823 to fight in Peru. This

depiction of perfectly uniformed troops moving in neat formation through the snow of the Andes, by the

Chilean artist Franco Gomez, is, of course, highly unrealistic.

492 CHAPTER 20 THE AMERICAS AND SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE WEST

forces ov er the high Andes M ountains, an amazing feat in

itself. Two-thirds of their pack mules and horses died

during the difficult journey. Many of the soldiers suffer ed

from lack of oxygen and severe cold while crossing

mountain passes more than 2 miles abov e sea level. The

arrival of San Martı

´

n’s troops in Chile completely surprised

theSpaniards,whoseforceswereroutedattheBattleof

Chacabuco on February 12, 1817.

In 1821, San Martı

´

n moved on to Lima, Peru, the

center of Spanish authority. Convinced that he was unable

to complete the liberation of all of Peru, San Martı

´

n

welcomed the arrival of Bolı

´

var and his forces. As he wrote

to Bolı

´

var, ‘‘For me it would have been the height of

happiness to end the war of independence under the or-

ders of a general to whom [South] America owes its

freedom. Destiny orders it otherwise, and one must resign

oneself to it.’’

3

Highly disappointed, San Martı

´

nleftSouth

America for Europe, where he remained until his death

in 1850. Mean while, Bolı

´

var took on the task of crushing the

last significant Spanish army at Ayacucho on December 9,

1824. By then, Peru, Uruguay, Paraguay, Colombia, Ven-

ezuela, Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile had all become free

states (see Map 20.1). In 1823, the Central American states

became independent and in 1838--1839 divided into five

republics (Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Costa Rica,

and Nicaragua). Earlier, in 1822, the prince regent of

Brazil had declared Brazil’s independence from Portugal.

Independence and the Monroe Doctrine In the early

1820s, only one major threat remained to the newly won

independence of the Latin American states. Reveling in

their success in crushing rebellions in Spain and Italy, the

victorious continental European powers favored the use

of troops to restore Spanish control in Latin America.

This time, Britain’s opposition to intervention prevailed.

Eager to gain access to an entire continent for investment

SIMO

´

N BOLI

´

VA R O N GOVERNMENT IN LATIN AMERICA

Simo

´

n Bolı

´

var is acclaimed as the man who liber-

ated Latin America from Spanish control. His inter-

est in history and the ideas of the Enlightenment

also led him to speculate on how Latin American

nations would be governed after their freedom was obtained.

This selection is taken from a letter written to the British

governor of Jamaica.

Simo

´

n Bolı

´

var, The Jamaica Letter

It is ...difficult to foresee the future fate of the New World, to set

down its political principles, or to prophesy what manner of govern-

ment it will adopt. ... We inhabit a world apart, separated by broad

seas. We are young in the ways of almost all the arts and sciences,

although in a certain manner, we are old in the ways of civilized

society. ... But we scarcely retain a vestige of what once was; we

are, moreover, neither Indian nor European, but a species midway

between the legitimate proprietors of this country and the Spanish

usurpers. In short, though Americans by birth we derive our rights

from Europe, and we have to assert these rights against the rights of

the natives, and at the same time we must defend ourselves against

the invaders. This places us in a most extraordinary and involved

situation. ...

The role of the inhabitants of the American hemisphere has

for centuries been purely passive. Politically they were non-existent.

We are still in a position lower than slavery, and therefore it is

more difficult for us to rise to the enjoyment of freedom. ... States

are slaves because of either the nature or the misuse of their con-

stitutions; a people is therefore enslaved when the government, by

its nature or its vices, infringes on and usurps the rights of the

citizen or subject. Applying these principles, we find that America

was denied not only its freedom but even an active and effective

tyranny. ...

It is harder, Montesquieu has written, to release a nation from

servitude than to enslave a free nation. This truth is proven by the

annals of all times, which reveal that most free nations have been put

under the yoke, but very few enslaved nations have recovered their

liberty. Despite the convictions of history, South Americans have

made efforts to obtain liberal, even perfect, institutions, doubtless out

of that instinct to aspire to the greatest possible happiness, which,

common to all men, is bound to follow in civil societies founded on

the principles of justice, liberty, and equality. But are we capable of

maintaining in proper balance the difficult charge of a republic? Is it

conceivable that a newly emancipated people can soar to the heights

of liberty ...? Such a marvel is inconceivable and without precedent.

There is no reasonable probability to bolster our hopes.

More than anyone, I desire to see America fashioned into the

greatest nation in the world, greatest not so much by virtue of her

area and wealth as by her freedom and glory. Although I seek per-

fection for the government of my country, I cannot persuade myself

that the New World can, at the moment, be organized as a great re-

public. Since it is impossible, I dare not desire it; yet much less do I

desire to have all America a monarchy because this plan is not only

impracticable but also impossible. Wrongs now existing could not

be righted, and our emancipation would be fruitless. The American

states need the care of paternal governments to heal the sores and

wounds of despotism and war.

Q

What problems did Bolı

´

var foresee for Spanish America’s

political future? Do you think he believed in democracy? Why or

why not?

LATIN AME RICA IN THE NINETEENTH AND EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURIES 493