Duiker William J., Spielvogel Jackson J. The Essential World History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHAPTER 21

THE HIGH TIDE OF IMPERIALISM

CHAPTER OUTLINE

AND FOCUS QUESTIONS

The Spread of Colonial Rule

Q

What were the causes of the new imperialism of the

nineteenth century, and how did it differ from European

expansion in earlier periods?

The Colonial System

Q

What types of administrative systems did the various

colonial powers establish in their colonies, and how

did these systems reflect the general philosophy of

colonialism?

India Under the British Raj

Q

What were some of the major consequences of British

rule in India, and how did they affect the Indian people?

Colonial Regimes in Southeast Asia

Q

Which Western countries were most active in seeking

colonial possessions in Southeast Asia, and what were

their motives in doing so?

Empire Building in Africa

Q

What factors were behind the ‘‘scramble for Africa,’’ and

what impact did it have on the continent?

The Emergence of Anticolonialism

Q

How did the subject peoples respond to colonialism,

and what role did nationalism play in their response?

CRITICAL THINKING

Q

What were the consequences of the new imperialism

of the nineteenth century for the colonies and the

colonial powers? How do you feel the imperialist

countries should be evaluated in terms of their motives

and stated objectives?

Revere the conquering heroes: Establishing British rule in Africa

c

Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

514

IN 1877, THE YOUNG British empire builder Cecil Rhodes

drew up his last will and testament. He bequeathed his fortune,

achieved as a diamond magnate in South Africa, to two of his close

friends and acquaintances. He also instructed them to use the inher-

itance to form a secret societ y with the aim of bringing about ‘‘the

extension of British rule throughout the world, the perfecting of a

system of emigration from the United Kingdom ...especially the

occupation by British settlers of the entire continent of Africa, the

Holy Land, the valley of the Euphrates, the Islands of Cyprus and

Candia [Crete], the whole of South America. ... The ultimate recov-

ery of the United States of America as an integral part of the British

Empire ...then finally the foundation of so great a power as to

hereafter render wars impossible and promote the best interests of

humanity.’’

1

Preposterous as such ideas sound today, they serve as a graphic

reminder of the hubris that characterized the worldview of Rhodes

and many of his contemporaries during the age of imperialism, as

well as the complex union of moral concern and vaulting ambition

that motivated their actions on the world stage.

Through their efforts, Western colonialism spread throughout

much of the non-Western world during the nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries. Spurred by the demands of the Industrial

The Spread of Colonial Rule

Q

Focus Question: What were the causes of the new

imperialism of the nineteenth century, and how did it

differ from European expansion in earlier periods?

In the nineteenth century, a new phase of Western ex-

pansion into Asia and Africa began. Whereas European

aims in the East before 1800 could be summed up in

Vasco da Gama’s famous phrase ‘‘Christians and spices,’’

now a new relationship took shape as European nations

began to view Asian and African societies as sources of

industrial raw materials and as markets for Western

manufactured goods. No longer were Western gold and

silver exchanged for cloves, pepper, tea, silk, and porce-

lain. Now the prodigious output of European factories

was sent to Africa and Asia in return for oil, tin, rubber,

and the other resources needed to fuel the Western

industrial machine.

The Motives

The reason for this change, of course, was the Industrial

Revolution. Now industrializing countries in the West

needed vital raw materials that were not available at home,

as well as a reliable market for the goods produced in their

factories. The latter factor became increasingly crucial as

producers began to disco v er that their home markets

could not always absorb domestic output and that they

had to export their manufactures to make a profit.

As Western economic expansion into Asia and Africa

gathered strength during the nineteenth century, it be-

came fashionable to call the process imperialism. Al-

though the term imperialism has many meanings, in this

instance it referred to the efforts of capitalist states in the

West to seize markets, cheap raw materials, and lucrative

avenues for investment in the countries beyond Western

civilization. In this interpretation, the primary motives

behind the Western expansion were economic. Promoters

of this view maintained that modern imperialism was a

direct consequence of the modern industrial economy.

As in the earlier phase of Western expansion, how-

ever, the issue was not simply an economic one. Eco-

nomic concerns were inevitably tinged with political

overtones and with questions of national grandeur and

moral purpose as well. In the minds of nineteenth-

century Europeans, economic wealth, national status, and

political power went hand in hand with the possession of

a colonial empire. To global strategists, colonies brought

tangible benefits in the world of balance-of-power politics

as well as economic profits, and many nations became

involved in the pursuit of colonies as much to gain

advantage over their rivals as to acquire territory for its

own sake.

The relationship between colonialism and national

survival was expressed directly in a speech by the French

politician Jules Ferry in 1885. A policy of ‘‘containment or

abstinence,’’ he warned, would set France on ‘‘the broad

road to decadence’’ and initiate its decline into a ‘‘third-

or fourth-rate power.’’ British imperialists, convinced by

the theory of social Darwinism that in the struggle be-

tween nations, only the fit are victorious and survive,

agreed. As the British professor of mathematics Karl

Pearson argued in 1900, ‘‘The path of progress is strewn

with the wrecks of nations; traces are everywhere to be

seen of the [slaughtered remains] of inferior races. ... Ye t

these dead people are, in very truth, the stepping stones

on which mankind has arisen to the higher intellectual

and deeper emotional life of today.’’

2

For some, colonialism had a moral purpose, whether

to promote Christianity or to build a better world. The

British colonial official Henry Curzon declared that the

British Empire ‘‘was under Providence, the greatest in-

strument for good that the world has seen.’’ To Cecil

Rhodes, the most famous empire builder of his day, the

extraction of material wealth from the colonies was only a

secondary matter. ‘‘My ruling purpose,’’ he remarked, ‘‘is

the extension of the British Empire.’’

3

That British Em-

pire, on which, as the saying went, ‘‘the sun never set,’’

was the envy of its rivals and was viewed as the primary

source of British global dominance during the second half

of the nineteenth century.

The Tactics

With the change in European motives for colonization

came a corresponding shift in tactics. Earlier, when their

economic interests were more limited, European states

had generally been satisfied to deal with existing inde-

pendent states rather than attempting to establish direct

control over vast territories. There had been exceptions

where state power at the local level was at the point of

collapse (as in India), where European economic interests

were especially intense (as in Latin America and the East

THE SPRE AD OF COLON IAL RULE 515

Revolution, a few powerful Western states---notably, Great Britain,

France, Germany, Russia, and the United States---competed ava-

riciously for consumer markets and raw materials for their expand-

ing economies. By the end of the nineteenth century, virtually all of

the traditional societies in Asia and Africa were under direct or indi-

rect colonial rule. As the new century began, the Western imprint on

Asian and African societies, for better or for worse, appeared to be a

permanent feature of the political and cultural landscape.

Indies), or where there was no centralized authority (as in

North America and the Philippines). But for the most

part, the Western presence in Asia and Africa had been

limited to controlling the regional trade network and

establishing a few footholds where the foreigners could

carry on trade and missionary activity.

After 1800, the demands of industrialization in Eur ope

created a new set of dynamics. Maintaining access to

industrial raw materials such as oil and rubber and setting

up reliable markets for European manufactured products

required more extensive control over colonial territories.

As competition for colonies increased, the colonial

powers sought to solidify their hold over their territories

to protect them from attack by their rivals. During the

last two decades of the nineteenth century, the quest for

colonies became a scramble as all the major European

states, now joined by the United States and Japan, en-

gaged in a global land grab. In many cases, economic

interests were secondary to security concerns or the re-

quirements of national prestige. In Africa, for example,

the British engaged in a struggle with their rivals to

protect their interests in the Suez Canal and the Red Sea.

By 1900, almost all the societies of Africa and Asia

were either under full colonial rule or, as in the case of

China and the Ottoman Empire, at a point of virtual

collapse. Only a handful of states, such as Japan in East

Asia, Thailand in Southeast Asia, Afghanistan and Iran in

the Middle East, and mountainous Ethiopia in East

Africa, managed to escape internal disintegration or

subjection to colonial rule. For the most part, the ex-

ceptions were the result of good fortune rather than

design. Thailand escaped subjugation primarily because

officials in London and Paris found it more convenient to

transform the country into a buffer state than to fight

over it. Ethiopia and Afghanistan survived due to their

remote location and mountainous terrain. Only Japan

managed to avoid the common fate through a concerted

strategy of political and economic reform.

The Colonial System

Q

Focus Question: What types of administrative systems

did the various colonial powers establish in their

colonies, and how did these systems reflect the general

philosophy of colonialism?

Now that they had control of most of the world, what did

the colonial powers do with it? As we have seen, their

primary objective was to exploit the natural resources of

the subject areas and to open up markets for manufac-

tured goods and capital investment from the mother

country. In some cases, that goal could be realized in

cooperation with local politi-

cal elites, whose loyalty could

be earned, or purchased, by

economic rewards or by con-

firming them in their posi-

tions of authority and status

in a new colonial setting.

Sometimes, however, this

policy of indirect rule was not

feasible because local leaders

refused to cooperate with

their colonial masters or even

actively resisted the foreign

conquest. In such cases, the

local elites were removed from

power and replaced with a

new set of officials recruited

from the mother country.

In general, the societies

most likely to actively resist

colonial conquest were those

with a long tradition of na-

tional cohesion and indepen-

dence, such as Burma and

Vietnam in Asia and the

African Muslim states in

northern Nigeria and Moroc co .

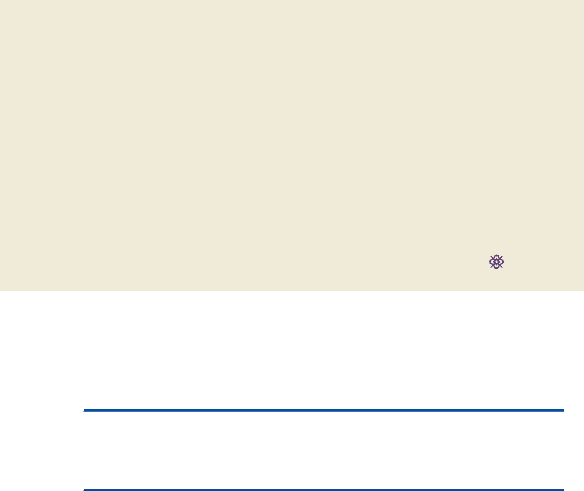

The Comp any Reside nt and His Puppet. The British East India Company gradually replaced the

sovereigns of the once-independent Indian states with puppet rulers who carried out the company’s policies.

Here we see the company’s resident dominating a procession in Tanjore in 1825, while the Indian ruler,

Sarabhoji, follows like an obedient shadow. As a boy, Sarabhoji had been educated by European tutors and had

filled his life and home with English books and furnishings.

c

Art Media, Victoria and Albert Museum, London/HIP/The Image Works

516 CHAPTER 21 THE HIGH TIDE OF IMPERIALISM

In those areas, the colonial powers tended to dispense with

local collaborators and govern directly. In parts of Africa,

the Indian subcontinent, and the Malay peninsula, where

the local authorities, for whatever reason, were willing to

collaborate with the imperialist powers, indirect rule was

more common.

Overall, colonialism in India, Southeast Asia, and

Africa exhibited many similarities but also some differ-

ences. Some of these variations can be traced to political

or social differences among the colonial powers them-

selves. The French, for example, often tried to impose a

centralized administrative system on their colonies that

mirrored the system in use in France, while the British

sometimes attempted to transform local aristocrats into

the equivalent of the landed gentry at home in Britain.

Other differences stemmed from conditions in the colo-

nies themselves.

The Philosophy of Colonialism

To justify their rule, the colonial powers appealed in part

to the time-honored maxim of ‘‘might makes right.’’ By

the end of the nineteenth century, that attitude received

pseudoscientific validity from the concept of social Dar-

winism, which maintained that only societies that moved

aggressively to adapt to changing circumstances would

survive and prosper in a world governed by the Dar-

winian law of ‘‘survival of the fittest.’’

Some people, however, were uncomfortable with

such a brutal view of the law of nature and sought a

moral justification that appeared to benefit the victim.

Here again, the concept of social Darwinism pointed the

way. By bringing the benefits of Western democracy,

capitalism, and Christianity to the tradition-ridden so-

cieties of Africa and Asia, the colonial powers were en-

abling primitive peoples to adapt to the challenges of the

modern world. Buttressed by such comforting theories,

sensitive Western minds could ignore the brutal aspects of

colonialism and persuade themselves that in the long run,

the results would be beneficial for both sides (see the

box on p. 518). Few were as adept at describing the

‘‘civilizing mission’’ of coloniali sm as the French ad-

ministrator and twice governor-general of French

Indochina Albert Sarraut. While admitting that colo-

nialism was originally an ‘‘act of force’’ undertaken for

commerc ial profit, he insisted that by red istributing the

wealth of the ear th, the colonial process would result in

a better life for all: ‘‘Is it just, is it legitimate that such

[an uneven distribution of resources] should be in-

definitely prolonged? ... No! ... Humanity is distrib-

uted throughout the globe. No race, no people has the

right or power to isolate itself egotistically from the

movements and necessities of universal life.’’

4

But what about the possibility that historically and

culturally the societies of Asia and Africa were funda-

mentally different from those of the West and could not,

or would not, be persuaded to transform themselves

along Western lines? In that case, a policy of cultural

transformation could not be expected to succeed and

could even lead to disaster.

Assimilation or Association? In fact, colonial theorists

never decided this issue one way or the other. The French,

who were most inclined to philosophize about the

problem, adopted the terms assimilation (which implied

an effort to transform colonial societies in the Western

image) and association (implying collaboration with lo-

cal elites while leaving local traditions alone) to describe

the two alternatives and then proceeded to vacillate be-

tween them. French policy in Indochina, for example,

began as one of association but switched to assimilation

under pressure from those who felt that colonial powers

owed a debt to their subject peoples. But assimilation

(which in any case was never accepted as feasible or de-

sirable by many colonial officials) aroused resentment

among the local population, many of whom opposed the

destruction of their native traditions. In the end, the

French abandoned the attempt to justify their presence

and fell back on a policy of ruling by force of arms.

Other colonial powers had little interest in the issue.

The British, whether out of a sense of pragmatism or of

racial superiority, refused to entertain the possibility of

assimilation and treated their subject peoples as culturally

and racially distinct.

India Under the British Raj

Q

Focus Question: What were some of the major

consequences of British rule in India, and how did

they affect the Indian people?

By 1800, the once glorious empire of the Mughals had

been reduced by British military power to a shadow of its

former greatness. During the next few decades, the British

sought to consolidate their control over the Indian sub-

continent, expanding from their base areas along the

coast into the interior. Some territories were taken over

directly, first by the East India Company and later by the

British crown; others were ruled indirectly through their

local maharajas and rajas.

Colonial Reforms

Not all of the effects of British rule were bad. British

governance over the subcontinent brought order and

INDIA UNDER THE BRITISH RAJ 517

stability to a society that had been rent by civil war. By the

early nineteenth century, British control had been con-

solidated and led to a relatively honest and efficient

government that in many respects operated to the benefit

of the average Indian. One of the benefits of the period

was the heightened attention given to education. Through

the efforts of the British administrator Thomas Babington

Macaulay, a new school system was established to train

the children of Indian elites, and the British civil service

examination was introduced (see the box on p. 519).

The instruction of young girls also expanded, with the

primary purpose of making them better wives and

mothers for the educated male population. In 1875, a

Madras medical college accepted its first female student.

British rule also brought an end to some of the more

inhumane aspects of Indian tradition. The practice of sati

was outlawed, and widows were legally permitted to re-

marry. The British also attempted to put an end to the

endemic brigandage (known as thug gee, which gave rise

to the English word thug) that had plagued travelers in

OPPOSING VIEWPOINTS

W

HITE MAN’S BURDEN,BLACK MAN’S SORROW

One of the justifications for modern imperialism

was the notion that the supposedly ‘‘more ad-

vanced’’ white peoples had a moral responsibility

to raise ‘‘ignorant’’ native peoples to a higher level

of civilization. Few captured this notion better than the British

poet Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936) in his famous poem The

White Man’s Burden. His appeal, directed to the United States,

became one of the most famous sets of verses in the English-

speaking world.

That sense of moral responsibility, however, was often mis-

placed or, even worse, laced with hypocrisy. All too often, the

consequences of imperial rule were detrimental to everyone liv-

ing under colonial authority. Few observers described the de-

structive effects of Western imperialism on the African people

as well as Edmund Morel, a British journalist whose book The

Black Man’s Burden pointed out some of the more harmful

aspects of colonialism in the Belgian Congo.

Rudyard Kipling, The White Man’s Burden

Take up the White Man’s burden---

Send forth the best ye breed---

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need;

To wait in heavy harness,

On fluttered folk and wild---

Your new-caught sullen peoples,

Half-devil and half-child.

Take up the White Man’s burden---

In patience to abide,

To veil the threat of terror

And check the show of pride;

By open speech and simple,

An hundred times made plain

To seek another’s profit,

And work another’s gain.

Take up the White Man’s burden---

The savage wars of peace---

Fill full the mouth of Famine

And bid the sickness cease;

And when your goal is nearest

The end for others sought,

Watch Sloth and heathen Folly

Bring all your hopes to nought.

Edmund Morel, The Black Man’s Burden

It is [the Africans] who carry the ‘‘Black man’s burden.’’ They have not

withered away before the white man ’s occupation. Indeed ...Africa has

ultimately absorbed within itself every Caucasian and, for that matter,

every Semitic invader, too. In hewing out for himself a fixed abode in

Africa, the white man has massacred the African in heaps. The African

has survived, and it is well for the white settlers that he has. ...

What the partial occupation of his soil by the white man has

failed to do; what the mapping out of European political ‘‘spheres of

influence’’ has failed to do; what the Maxim and the rifle, the slave

gang, labour in the bowels of the earth and the lash, have failed to

do; what imported measles, smallpox and syphilis have failed to do;

whatever the overseas slave trade failed to do; the power of modern

capitalistic exploitation, assisted by modern engines of destruction,

may yet succeed in accomplishing.

For from the evils of the latter, scientifically applied and

enforced, there is no escape for the African. Its destructive effects

are not spasmodic; they are permanent. In its permanence resides its

fatal consequences. It kills not the body merely, but the soul. It

breaks the spirit. It attacks the African at every turn, from every

point of vantage. It wrecks his polity, uproots him from the land,

invades his family life, destroys his natural pursuits and occupations,

claims his whole time, enslaves him in his own home.

Q

According to Kipling, why should Western nations take up

the ‘‘white man’s burden,’’ as described in this poem? What

was the ‘‘black man’s burden,’’ in the eyes of Edmund Morel?

518 CHAPTER 21 THE HIGH TIDE OF IMPERIALISM

India since time immemorial. Railroads, the telegraph,

and the postal service were introduced to India shortly

after they appeared in Great Britain itself. Work began on

the main highway from Calcutta to Delhi in 1839 (see

Map 21.1), and the first rail network in northern India

was opened in 1853.

The Costs of Colonialism

But the Indian people paid a high price for the peace and

stability brought by the British raj (from the Indian raja,

or prince). Perhaps the most flagrant cost was economic.

While British entrepreneurs and a small percentage of the

Indian population attached to the imperial system reaped

financial benefits from British rule, it brought hardship to

millions of others in both the cities and the rural areas.

The introduction of British textiles put thousands of

Bengali women out of work and severely damaged the

local textile industry.

In rural areas, the British introduced the zamindar

system (see Chapter 16) in the misguided expectation

that it would both facilitate the collection of agricultural

taxes and create a new landed gentry, who could, as in

Britain, become the conservative foundation of imperial

rule. But the local gentry took advantage of this new

authority to increase taxes and force the less fortunate

peasants to become tenants or lose their land entirely.

British officials also made few efforts during the nine-

teenth century to introduce democratic institutions or

values to the Indian people. As one senior political figure

remarked in Parliament in 1898, democratic institutions

‘‘can no more be carried to India by Englishmen ...than

they can carry ice in their luggage.’’

5

British colonialism was also remiss in bringing the

benefits of modern science and technology to India. Some

limited forms of industrialization took place, notably in

the manufacturing of textiles and jute (used in making

rope). The first textile mill opened in 1856. Seventy years

later, there were eighty mills in the city of Bombay (now

Mumbai) alone. Nevertheless, the lack of local capital

and the advantages given to British imports prevented

the emergence of other vital new commercial and

manufacturing operations.

Foreign rule also had a psychological effect on the

Indian people. Although many British colonial officials

sincerely tried to improve the lot of the people under

INDIAN IN BLOOD,ENGLISH IN TASTE AND I NTELLECT

Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800–1859) was

named a member of the Supreme Council of India

in the early 1830s. In that capacity, he was re-

sponsible for drawing up a new educational policy

for British subjects in the area. In his Minute on Education, he

considered the claims of English and various local languages to

become the vehicle for educational training and decided in favor

of the former. It is better, he argued, to teach Indian elites about

Western civilization so as ‘‘to form a class who may be inter-

preters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of

persons, Indian in blood and color, but English in taste, in opin-

ions, in morals, and in intellect.’’ Later Macaulay became a

prominent historian. The debate over the relative benefits of

English and the various Indian languages continues today.

Thomas Babington Macaulay, Minute on Education

We have a fund to be employed as government shall direct for the

intellectual improvement of the people of this country. The simple

question is, what is the most useful way of employing it?

All par ties seem to be agreed on one point, that the dialects

commonly spoken among the natives of this part of India contain

neither literary or scientific information, and are, moreover so poor

and rude that, until they are enriched from some other quarter, it

will not be easy to translate any valuable work into them. ...

What, then, shall the language [of education] be? One half of

the Committee maintain that it should be the Eng lish. The other

half strongly recommend the Arabic and Sanskrit. The whole

question seems to me to be, which language is the best worth

knowing?

I have no knowledge of either Sanskrit or Arabic---but I have

done what I could to form a correct estimate of their value. I have

read translations of the most celebrated Arabic and Sanskrit works.

I have conversed both here and at home with men distinguished by

their proficiency in the Eastern tongues. I am quite ready to take

the Oriental learning at the valuation of the Orientalists themselves.

I have never found one among them who could deny that a single

shelf of a good European librar y was worth the whole native litera-

ture of India and Arabia. ...

It is, I believe, no exaggeration to say, that all the historical in-

formation which has been collected from all the books w ritten in

the Sanskrit language is less valuable than what may be found in the

most paltry abridgments used at preparatory schools in England. In

every branch of physical or moral philosophy the relative position of

the two nations is nearly the same.

Q

How did the author of this document justify the teaching

of the English language in India? How might a critic have

responded?

INDIA UNDER THE BRITISH RAJ 519

their charge, British arrogance and contempt for native

tradition cut deeply into the pride of many Indians, es-

pecially those of high caste, who were accustomed to a

position of superior status in India. Educated Indians

trained in the Anglo-Indian school system for a career in

the civil service, as well as Eurasians born to mixed

marriages, often imitated the behavior and dress of their

rulers, speaking English, eating Western food, and taking

up European leisure activities, but many rightfully won-

dered where their true cultural loyalties lay (see the

comparative illustration on p. 521).

Colonial Regimes

in Southeast Asia

Q

Focus Question: Which Western countries were most

active in seeking colonial possessions in Southeast

Asia, and what were their motives in doing so?

In 1800, only two societies in Southeast Asia were under

effective colonial rule: the Spanish Philippines and the

Dutch East Indies. During the nineteenth century, how-

ever, European interest in South-

east Asia increased rapidly, and

by 1900, virtually the entire area

was under colonial rule (see

Map 21.2 on p. 522).

‘‘Opportunity in the Orient’’:

The Colonial Takeover

in Southeast Asia

The process began after the Na-

poleonic wars, when the British,

by agreement with the Dutch,

abandoned their claims to terri-

torial possessions in the East In-

dies in return for a free hand in

the Malay peninsula. In 1819, the

colonial administrator Stamford

Raffles founded a new British

colony on the island of Singapore

at the tip of the peninsula. Singa-

pore became a major stopping

point for traffic en route to and

from China and other commercial

centers in the region.

During the next few decades,

the pace of European penetration

into Southeast Asia accelerated.

The British attacked lower Burma

in 1826 and eventually established

control over Burma, arousing fears

in France that its British rival

might soon aquire a monopoly of

trade in South China. In 1857, the

French government decided to

compel the Vietnamese to accept

French protection. A naval attack

launched a year later was not a

total success, but the French

eventually forced the Nguyen dy-

nasty in Vietnam to cede territo-

ries in the Mekong River delta.

Arabian Sea

Bay of Bengal

I

n

d

u

s

R

.

G

a

n

g

e

s

R

.

T

i

s

t

a

R

.

RAJPUTANA

UNITED

PROVINCES

BIHAR

AND

ORISSA

BENGAL

ASSAM

TIBET

CENTRAL

PROVINCES

BURMA

HYDERABAD

BOMBAY

MYSORE

CEYLON

(CROWN

COLONY)

CHINA

AFGHANISTAN

Karachi

Delhi

Cawnpore

Lucknow

Varanasi

(Benares)

Patna

Calcutta

Bombay

Goa

Madras

Pondicherry

Cochin

PUNJAB

KASHMIR

AND

JAMMU

Amritsar

Lahore

SIND

Agra

0 250 500 Miles

0 250 500 750 Kilometers

Territory under British rule

Territories permanently administered

by government of India (mostly tribal)

States and territories under Indian

administration

Portuguese enclave

French enclave

Hindu-majority provinces

Muslim-majority provinces

Area of large Sikh population

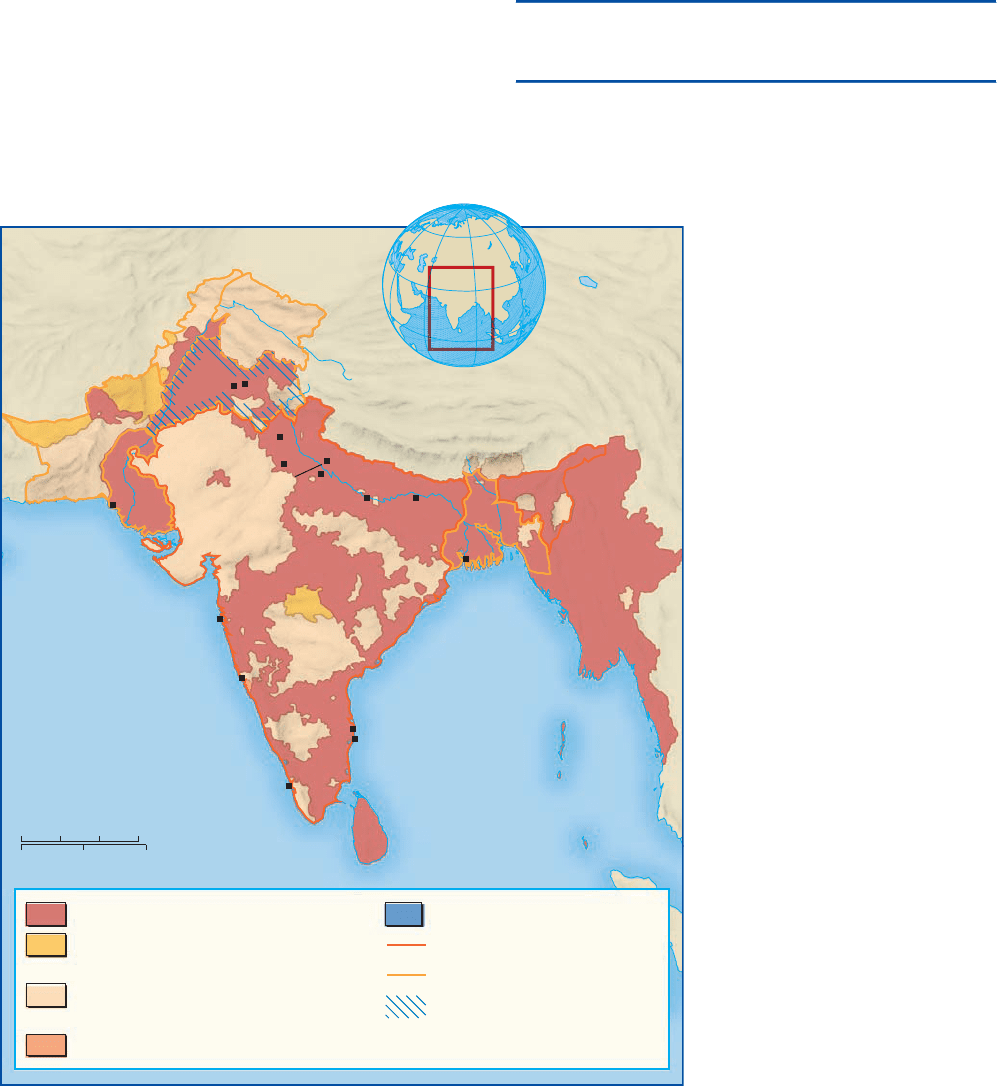

MAP 21.1 India Under British Rule, 1805–1931. This map shows the different

forms of rule that the British applied in India under their control.

Q

Where were the major cities of the subcontinent located, and under whose rule did

they fall?

520 CHAPTER 21 THE HIGH TIDE OF IMPERIALISM

A generation later,

French rule was ex-

tended over the re-

mainder of the country.

By 1900, Frenc h se izure

of neighboring Cam-

bodia and Laos had led

to the creation of the

French-ruled Indochi-

nese Union.

After the French

conquest of Indochina,

Thailand was the only

remaining independent state on the S outheast Asian

mainland. Under the astute leadership of two remark-

able rulers, King Mongkut and his son, King

Chulalongkorn, the Thai attempted to introduce

Western learning and maintain relations w ith the major

European powers without undermining internal stabil-

ity or inviting an imperialist attack. In 1896, the British

and the French agreed to preserve Thailand as an in-

dependent buffer zone between their possessions in

Southeast Asia.

The final piece in the colonial edifice in Southeast

Asia was put in place during the Spanish-American

War in 1898 (see Chapter 20), when U.S. naval forces

under Commodore George Dewey defeated the Spanish

fleet in Manila Bay. President Wil liam McKinley ago-

nized over the fate of the Philippines but ultimately

decided that the moral thing to do was to turn the is-

lands into an American colony to prevent them from

falling into the hands of the Japanese. In fact, the

Americans (like the Spanish before them) found the

islands a convenient jumping-off point for the China

trade(seeChapter22).Themixtureofmoralidealism

and the desire for profit was reflected in a speech given

COMPARATIVE ILLUSTRATION

Cultural Influences—East and West. When Europeans moved into Asia in the

nineteenth century, some Asians began to imitate European customs for prestige

or social advancement. Seen at the left, for example, is a young Vietnamese

during the 1920s dressed in Western sports clothes, learning to play tennis. Sometimes,

however, the cultural influence went the other way. At the right, an English nabob, as

European residents in India were often called, apes the manner of an Indian aristocrat,

complete with harem and hookah, the Indian water pipe. The paintings on the wall, however,

are in the European style.

Q

Compare and c ontrast the styles used by the artists in these two paintings.

What message do they send to the viewer?

c

Archives Charmet/The Bridgeman Art Library

c

Werner Forman/Art Resource, NY

SUMATRA

MALAYA

Singapore

S

t

r

a

i

t

o

f

M

a

l

a

c

c

a

Malacca

200 Kilometers0

0 150 Miles

Singapore and Malaya

COLONIAL REGIMES IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 521

VIETNAM

(1859)

LAOS

(1893)

CAMBODIA

(1863)

THAILAND

BURMA

(1826)

MALAYA

(1786)

SINGAPORE

(1819)

SARAWAK

(1888)

BRUNEI

(1888)

NORTH BORNEO

(1888)

INDONESIA (early 1600s)

TIMOR (1566)

PHILIPPINES

(Spain, 1521;

United

States, 1898)

MALACCA

(Port., 1511)

CHINA

NEW

GUINEA

Portuguese

Spanish and American

Dutch

British

French

Not colonized

Date of initial claim

or control

(1895)

0 500 1,000 Miles

0 500 1,000 1,500 Kilometers

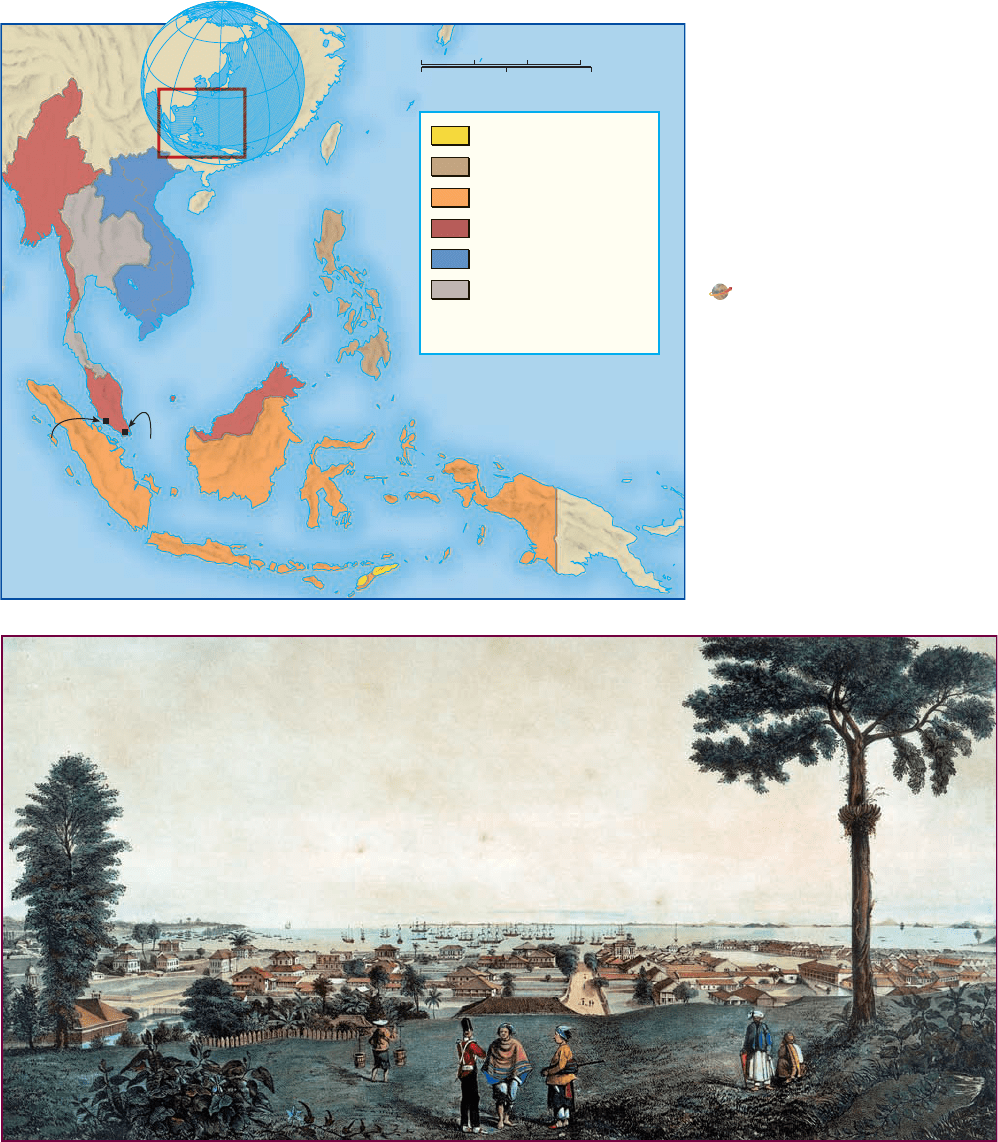

MAP 21.2 Colonial Southea st

Asia.

This map shows the spread of

European colonial rule into Southeast

Asia from the sixteenth century to the

end of the nineteenth. Malacca,

initially seized by the Portuguese in

1511, was taken by the Dutch in the

seventeenth century and then by the

British one hundred years later.

Q

What was the significanc e of

Malacca?

Vi ew an animated version

of this map or related maps at

www .cengage.com/history/duikspiel/

essentialworld6e

c

British Library/HIP/Art Resource, NY

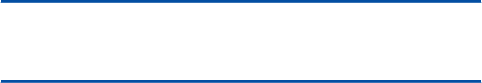

Government Hill in Singapore. After occupying the island of Singapore early in the nineteenth century, the

British turned what was once a pirate lair at the entrance to the Strait of Malacca into one of the most important

commercial seaports in Asia. By the end of the century, Singapore was home to a rich mixture of peoples, both

European and Asian. This painting by a British artist in the mid-nineteenth century graphically displays the multiracial

character of the colony as strollers of various ethnic backgrounds share space on Government Hill, with the busy

harbor in the background. Almost all colonial port cities became melting pots of people from various parts of the

world. Many of the immigrants served as merchants, urban laborers, and craftsmen in the new imperial marketplace.

522 CHAPTER 21 THE HIGH TIDE OF IMPERIALISM

in the U.S. Senate in January 1900 by Senator Albert

Beveridge of Indiana:

Mr. President, the times call for candor. The Philippines are

ours forever, ‘‘territory belonging to the United States,’’ as the

Constitution calls them. And just beyond the Philippines are

China’s illimitable markets. We will not retreat from

either. ... We will not renounce our part in the mission of

our race, trustee, under God, of the civilization of the world.

And we will move forward to our work, not howling out

regrets like slaves whipped to their burdens, but with grati-

tude for a task worthy of our strength, and thanksgiving to

Almighty God that He has marked us as His chosen people,

henceforth to lead in the regeneration of the world.

6

Not all Filipinos agreed with Senator Beveridge’s

portrayal of the situation. Under the leadership of Emilio

Aguinaldo, guerrilla forces fought bitterly against U.S.

troops to establish their independence from both Spain

and the United States. But America’s first war against

guerrilla forces in Asia was a success, and the bulk of the

resistance collapsed in 1901. President McKinley had his

stepping-stone to the rich markets of China.

The Nature of Colonial Rule

In Southeast Asia, economic profit was the immediate

and primary aim of colonial enterprise. For that purpose,

colonial powers tried wherever possible to work w ith local

elites to facilitate the exploitation of natural resources.

Indirect rule reduced the cost of training European ad-

ministrators and had a less corrosive impact on the local

culture. In the Dutch East Indies, for example, officials of

the Dutch East India Company (VOC) entrusted local

administration to the indigenous landed aristocracy, who

maintained law and order and collected taxes in return

for a payment from the VOC. The British followed a

similar practice in Malaya. While establishing direct rule

over the crucial commercial centers of Singapore and

Malacca, the British allowed local Muslim rulers to

maintain princely power in the interior of the peninsula.

Administration and Education Indirect rule, however

convenient and inexpensive, was not always feasible. In

some instances, local resistance to the colonial conquest

made such a policy impossible. In Burma, the staunch

opposition of the monarchy and other traditionalist

forces caused the British to abolish the monarchy and

administer the country directly through their colonial

government in India. In Indochina, the French used both

direct and indirect means. They imposed direct rule on

the southern provinces in the Mekong delta but governed

the north as a protectorate, with the emperor retaining

titular authority from his palace in Hue

ˆ

. The French

adopted a similar policy in Cambodia and Laos, where

local rulers were left in charge with French advisers to

counsel them.

Whatever method was used, colonial regimes in

Southeast Asia, as elsewhere, were slow to create demo-

cratic institutions. The first legislative councils and as-

semblies were composed almost exclusively of European

residents in the colony. The first representatives from the

indigenous population were wealthy and conservative in

their political views. When Southeast Asians complained,

colonial officials gradually and reluctantly began to

broaden the franchise. Albert Sarraut advised patience in

awaiting the full benefits of colonial policy: ‘‘I will treat

you like my younger brothers, but do not forget that I am

the older brother. I will slowly give you the dignity of

humanity.’’

7

Colonial officials were also slow to adopt educational

reforms. Although the introduction of Western education

was one of the justifications of colonialism, colonial of-

ficials soon discovered that educating native elites could

backfire. Often there were few jobs for highly trained

lawyers, engineers, and architects in colonial societies,

leading to the threat of an indigestible mass of unem-

ployed intellectuals who would take out their frustrations

on the colonial regime. As one French official noted in

voicing his opposition to increasing the number of

schools in Vietnam, educating the natives meant not ‘‘one

coolie less, but one rebel more.’’

Economic Development Colonial powers were equally

reluctanttotakeupthe‘‘whiteman’sburden’’inthe

area of economic development. As we have seen, their

primary goals were to secure a source of cheap raw

materials and to maintain markets for manufactured

goods. Such objectives would be undermined by the

emergence of advanced industrial economies. So colonial

policy concentrated on the export of raw materials---

teakwood from Burma; rubber and tin from Malaya;

spices, tea and coffee, and palm oil from the East Indies;

and sugar and copra (the meat of a coconut) from the

Philippines.

CHRONOLOGY

Imperialism in Asia

Stamford Raffles arrives in Singapore 1819

British attack lower Burma 1826

British rail network opens in northern India 1853

Sepoy Rebellion 1857

French attack Vietnam 1858

British and French agree to neutralize Thailand 1896

Commodore Dewey defeats Spanish fleet in Manila Bay 1898

French create Indochinese Union 1900

C

OLONIAL REGIMES IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 523