Duiker William J., Spielvogel Jackson J. The Essential World History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

organization called Can Vuong (literally ‘‘sav e the king’’)

and continued their resistance without imperial sanction

(see the box on p. 535).

The first stirrings of nationalism in India took place

in the early nineteenth century with the search for a re-

newed sense of cultural identity. In 1828, Ram Mohan

Roy, a brahmin from Bengal, founded the Brahmo Samaj

(Society of Brahma). Roy probably had no intention of

promoting Indian national independence but created the

new organization as a means of helping his fellow reli-

gionists defend the Hindu religion against verbal attacks

by their British acquaintances.

Sometimes traditional resistance to Western penetra-

tion went beyond elite circles. Most commonly, it ap-

peared in the form of peasant revolts. Rural rebellions

were not uncommon in traditional Asian societies as a

means of expressing peasant discontent with high taxes,

official corruption, rising rural debt, and famine in the

countryside. Under colonialism, rural conditions often

deteriorated as population density increased and peasants

were driven off the land to make way for plantation

agriculture. Angry peasants then vented their frustration at

the foreign invaders. For example, in Burma, the Buddhist

monk Saya San led a peasant uprising against the British

many years after they had completed their takeover.

The Sepoy Rebellion Sometimes the resentment had a

religious basis, as in the Sudan, where the revolt led by the

Mahdi had strong Islamic overtones, although it was ini-

tially provok ed by Turkish misrule in Egypt. More signif-

icant than Roy’s Brahmo Samaj in its impact on British

policy was the famous Sepoy R ebellion of 1857 in India.

The sepoys (deriv ed from sipahi, a Turkish word meaning

horseman or soldier) were native troops hired by the East

India Company to protect British inter ests in the region.

U nrest within Indian units of the c olonial army had been

common since early in the century, when it had been

sparked by economic issues, religious sensitivities, or na-

scent anticolonial sentiment. In 1857, tension erupted

when the British adopted the new Enfield rifle for use by

sepoy infantrymen. The new weapon was a muzzle loader

that used paper cartridges cover ed with animal fat and

THE CIVILIZING MISSION IN EGYPT

In many parts of the colonial world, European

occupation served to sharpen class divisions in

traditional societies. Such was the case in Egypt,

where the British protectorate, established in the

early 1880s, benefited many elites, who profited from the intro-

duction of Western culture. Ordinary Egyptians, less inclined to

adopt foreign ways, seldom profited from the European presence.

In response, British administrators showed little patience for their

subjects who failed to recognize the superiority of Western civili-

zation. This view found expression in the words of the governor-

general, Lord Cromer, who remarked in exasperation, ‘‘The mind

of the Oriental, ...like his picturesque streets, is eminently want-

ing in symmetry. His reasoning is of the most slipshod descrip-

tion.’’ Cromer was especially irritated at the local treatment of

women, arguing that the seclusion of women and the wearing of

the veil were the chief causes of Islamic backwardness.

Such views were echoed by some Egyptian elites, who were

utterly seduced by Western culture and embraced the colonialists’

condemnation of native ways. The French-educated lawyer Qassim

Amin was one example. His book The Liberation of Women, pub-

lished in 1899 and excerpted here, precipitated a heated debate

between those who considered Western nations the liberators of

Islam and those who reviled them as oppressors.

Qassim Amin, The Liberation of Women

European civilization advances with the speed of steam and electric-

ity, and has even overspilled to every part of the globe so that there

is not an inch that he [European man] has not trodden underfoot.

Any place he goes he takes control of its resources ...and turns

them into profit ...and if he does harm to the original inhabitants,

it is only that he pursues happiness in this world and seeks it wher-

ever he may find it. ... For the most part he uses his intellect, but

when circumstances require it, he deploys force. He does not seek

glory from his possessions and colonies, for he has enough of this

through his intellectual achievements and scientific inventions.

What drives the Englishman to dwell in India and the French in

Algeria ...is profit and the desire to acquire resources in countries

where the inhabitants do not know their value or how to profit

from them.

When they encounter savages they eliminate them or drive

them from the land, as happened in America ...and is happening

now in Africa. ... When they encounter a nation like ours, with a

degree of civ ilization, with a past, and a religion ...and customs

and ...institutions ...they deal w ith its inhabitants kindly. But

they do soo n acquire its most valuable resources, because they

have greater wealth and intellect and knowledge and force. ...

[The veil constituted] a huge barrier between woman and her

elevation, and consequently a barrier between the nation and

its advance.

Q

Why did the author believe that Western culture would be

beneficial to Egyptian society? How might a critic of colonialism

have responded?

534 CHAPTER 21 THE HIGH TIDE OF IMPERIALISM

lard; because the cartridge had to be bitten off, it br oke

strictures against high-class Hindus’ eating animal prod-

ucts and M uslim prohibitions against eating pork. Protests

among sepo y units in northern India turned into a full-

scale mutin y, supported b y uprisings in rural districts in

various parts of the country. But the r ev olt lacked clear

goals, and rivalries between Hindus and Muslims and

discord among the leaders within each community pre-

vented coordination of operations. Although Indian troops

often fought bra v ely and outnumbered the British six to

one, they were poorly organized, and the British forces

(supplemented in many cases by sepoy troops) suppressed

the rebellion. Still, the revolt frightened the British, who

introduced a number of reforms and suppressed the final

OPPOSING VIEWPOINTS

T

O RESIST OR NOT TO RESIST

How to respond to the imposition of colonial rule

was sometimes an excruciating problem for politi-

cal elites in many Asian countries. Not only did re-

sistance often seem futile but it could even add to

the suffering of the indigenous population. Hoang Cao Khai and

Phan Dinh Phung were members of the Confucian scholar-gentry

from the same village in Vietnam. Yet they reacted in dramati-

cally different ways to the French conquest of their country.

Their exchange of letters, reproduced here, illustrates the

dilemmas they faced.

Hoang Cao Khai’s Letter to Phan Dinh Phung

Soon, it will be seventeen years since we ventured upon different

paths of life. How sweet was our friendship when we both lived

in our village. ... At the time when the capital was lost and after

the royal carriage had departed, you courageously answered the

appeals of the King by raising the banner of righteousness. It was

certainly the only thing to do in those circumstances. No one will

question that.

But now the situation has changed and even those without in-

telligence or education have concluded that nothing remains to be

saved. How is it that you, a man of vast understanding, do not

realize this? ...You are determined to do whatever you deem

righteous. ... But though you have no thoughts for your own per-

son or for your own fate, you should at least attend to the sufferings

of the population of a whole region. ...

Until now your actions have undoubtedly accorded with your

loyalty. May I ask however what sin our people have committed to

deserve so much hardship? I would understand your resistance, did

you involve but your family for the benefit of a large number. As of

now, hundreds of families are subject to grief; how do you have the

heart to fight on? I venture to predict that, should you pursue your

struggle, not only will the population of our village be destroyed but

our entire country will be transformed into a sea of blood and a

mountain of bones. It is my hope that men of your superior moral-

ity and honesty will pause a while to appraise the situation.

Reply of Phan Dinh Phung to Hoang Cao Khai

In your letter, you revealed to me the causes of calamities and

of happiness. You showed me clearly where advantages and

disadvantages lie. All of which sufficed to indicate that your anxious

concern was not only for my own security but also for the peace

and order of our entire region. I understood plainly your sincere

arguments.

I have concluded that if our country has survived these past

thousand years when its territory was not large, its army not strong,

its wealth not great, it was because the relationships between king

and subjects, fathers and children, have always been regulated by the

five moral obligations. In the past, the Han, the Sung, the Yuan, the

Ming time and again dreamt of annexing our country and of divid-

ing it up into prefectures and districts within the Chinese adminis-

trative system. But never were they able to realize their dream. Ah!

if even China, which shares a common border with our territory,

and is a thousand times more powerful than Vietnam, could not

rely upon her strength to swallow us, it was surely because the

destiny of our country had been willed by Heaven itself.

The French, separated from our country until the present day

by I do not know how many thousand miles, have crossed the

oceans to come to our country. Wherever they came, they acted like

a storm, so much so that the Emperor had to flee. The whole coun-

try was cast into disorder. Our rivers and our mountains have been

annexed by them at a stroke and turned into a foreign territory.

Moreover, if our region has suffered to such an extent, it was

not only from the misfortunes of war. You must realize that wher-

ever the French go, there flock around them groups of petty men

who offer plans and tricks to gain the enemy’s confidence. ... They

use ever y expedient to squeeze the people out of their possessions.

That is how hundreds of misdeeds, thousands of offenses have been

perpetrated. How can the French not be aware of all the suffering

that the rural population has had to endure? Under these circum-

stances, is it surprising that families should be disrupted and the

people scattered?

My friend, if you are troubled about our people, then I advise

you to place yourself in my position and to think about the circum-

stances in which I live. You will understand naturally and see clearly

that I do not need to add anything else.

Q

Explain briefly the reasons advanced by each writer to

justify his actions. Which argument do you think would have

earned more support from contemporaries? Why?

THE EMERGENCE OF ANTICOLONIALISM 535

remnants of the M ughal dynasty, which had supported the

mutiny; r esponsibility for governing the subcontinent was

then turned over to the crown.

Like the Sepoy Rebellion, traditional resistance

movements usually met with little success. Peasants armed

with pikes and spears were no match for Western armies

possessing the most terrifying weapons then known to

human society. In a few cases, such as the revolt of the

Mahdi at Khartoum, the natives were able to defeat the

invaders temporarily. But such successes were rare, and

the late nineteenth century witnessed the seemingly in-

exorable march of the Western powers, armed with the

Gatling gun (the first rapid-fire weapon and the precursor

of the modern machine gun), to mastery of the globe.

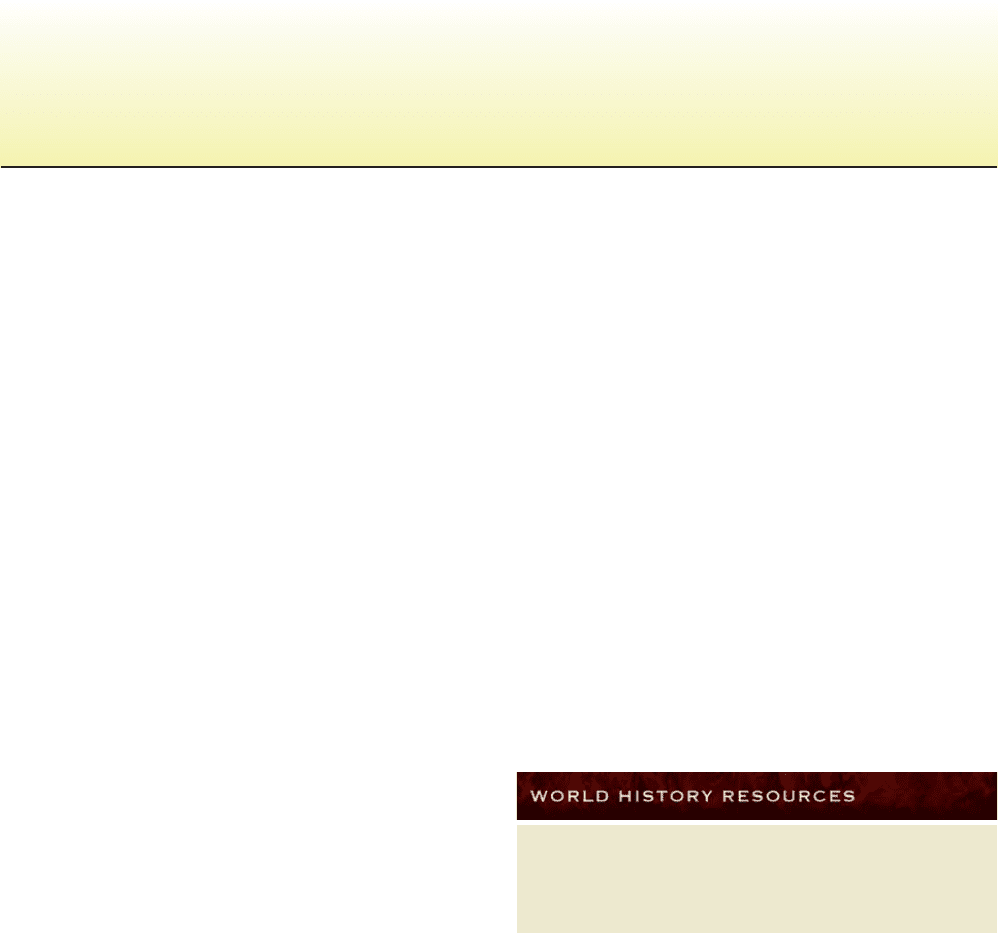

COMPARATIVE ESSAY

I

MPERIALISM:THE BALANCE SHEET

Few periods of history are as controversial

among scholars and casual observers as

the era of imperialism. To defenders of the

colonial enterprise like the poet Rudyard

Kipling, imperialism was the ‘‘white man’s burden,’’ a

disagreeable but necessary phase in the evolution of

human society, lifting up the toiling races from tradition

to modernity and bringing an end to poverty, famine,

and disease (see the box on p. 518).

Critics took exception to such views, portraying imperialism

as a tragedy of major proportions. The insatiable drive of

the advanced economic powers for access to raw materials

and markets created an exploitative environment that trans-

formed the vast majority of colonial peoples into a perma-

nent underclass, while restricting the benefits of modern

technology to a privileged few. Kipling’s ‘‘white man’s bur-

den’’ was dismissed as a hypocritical gesture to hoodwink

the naive and salve the guilty feelings of those who recog-

nized imperialism for what it was---a savage act of rape.

Defenders of the colonial experiment sometimes con-

cede that there were gross inequities in the colonial system

but point out that there was a positive side to the experi-

ence as well. The expansion of markets and the beginnings

of a modern transportation and communications network, while

bringing few immediate benefits to the colonial peoples, laid the

groundwork for future economic growth. At the same time, the in-

troduction of new ways of looking at human freedom, the relation-

ship between the individual and society, and democratic principles

set the stage for the adoption of such ideas after the restoration of

independence following World War II. Finally, the colonial experi-

ence offered a new approach to the traditional relationship between

men and women. Although colonial rule was by no means uni-

formly beneficial to the position of women in African and Asian so-

cieties, growing awareness of the struggle for equality by women in

the West offered their counterparts in the colonial territories a

weapon to fight against the long-standing barriers of custom and

legal discrimination.

How, then, are we to draw up a final balance sheet on the era

of Western imperialism? Both sides have good points to make, but

perhaps the critics have the best of the argument. Although the co-

lonial authorities sometimes did provide the beginnings of an infra-

structure that could eventually serve as the foundation of an

advanced industrial society, all too often they sought to prevent the

rise of industrial and commercial sectors in their colonies that

might provide competition to producers in the home country. So-

phisticated, age-old societies that could have been left to respond to

the technological revolution in their own way were thus squeezed

dry of precious national resources under the false guise of a ‘‘civiliz-

ing mission.’’ As the sociologist Clifford Geertz remarked in his

book Agricultural Involution: The Processes of Ecological Change in

Indonesia, the tragedy is not that the colonial peoples suffered

through the colonial era but that they suffered for nothing.

Q

Based on the information available to you, do you think

the imperialistic practices of the nineteenth and twentieth

centuries can be justified on moral or political grounds?

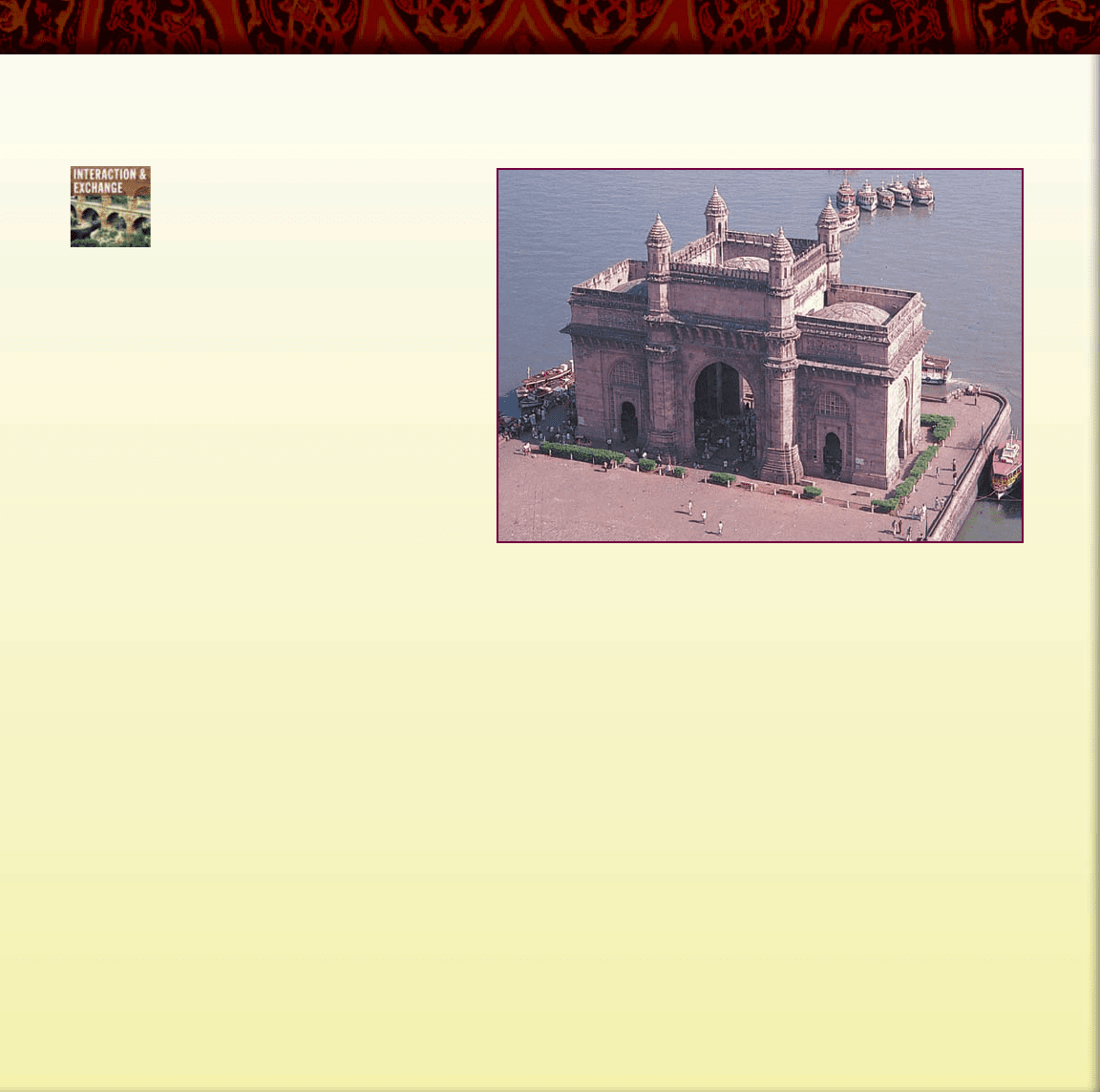

Gateway to India. Built in the Roman imperial style by the British to

commemorate the visit to India of King George V and Queen Mary in 1911, the

Gateway to India was erected at the water’s edge in the harbor of Bombay (now

Mumbai), India’s greatest port city. For thousands of British citizens arriving in

India, the Gateway to India was the first view of their new home and a symbol

of the power and majesty of the British raj.

c

William J. Duiker

536 CHAPTER 21 THE HIGH TIDE OF IMPERIALISM

TIMELINE

1800

1820 1840 1860 1880 1900

Africa

India

Southeast Asia

Slave trade declared

illegal in Great Britain

Sepoy Rebellion

Stamford Raffles

founds Singapore

First French attack

on Vietnam

Commodore Dewey defeats

Spanish fleet in Manila Bay

French and British agree

to neutralize Thailand

French protectorates

in Indochina

British rail network opened in northern India

French seize Algeria Boer War

Berlin Conference

on Africa

Opening of Suez Canal

CONCLUSION

BY THE FIRST QUARTER of the twentieth century, virtually

all of Africa and a good part of South and Southeast Asia were

under some form of colonial rule. With the advent of the age of

imperialism, a global economy was finally established, and the

domination of Western civilization over those of Africa and Asia

appeared to be complete.

Defenders of colonialism argue that the system was a necessary

if painful stage in the evolution of human societies. Critics,

however, charge that the Western colonial powers were driven by an

insatiable lust for profits (see the comparative essay ‘‘Imperialism:

The Balance Sheet’’ on p. 536). They dismiss the Western civilizing

mission as a fig leaf to cover naked greed and reject the notion that

imperialism played a salutary role in hastening the adjustment

of traditional societies to the demands of industrial civilization.

In the blunt words of two Western critics of imperialism: ‘‘Why is

Africa (or for that matter Latin America and much of Asia)

so poor? ...The answer is very brief: we have made it

poor.’’

10

Between these two irreconcilable views, where does the truth lie?

This chapter has contended that neither extreme position is justified.

Although colonialism did introduce the peoples of Asia and Africa to

new technology and the expanding economic marketplace, it was

unnecessarily brutal in its application and all too often failed to

realize the exalted claims and objectives of its promoters. Existing

economic networks---often potentially valuable as a foundation for

later economic development---were ruthlessly swept aside in the

interests of providing markets for Western manufactured goods.

Potential sources of native industrialization were nipped in the bud to

avoid competition for factories in Amsterdam, London, Pittsburgh,

or Manchester. Training in Western democratic ideals and practices

was ignored out of fear that the recipients might use them as

weapons against the ruling authorities.

The fundamental weakness of colonialism, then, was that it

was ultimately based on the self-interests of the citizens of the

colonial powers. Where those interests collided with the needs of

the colonial peoples, those of the former always triumphed.

CONCLUSION 537

SUGGESTED READING

Imperialism and Colonialism There are a number of good

works on the subject of imperialism and colonialism. For a study

that directly focuses on the question of whether colonialism was

beneficial to subject peoples, see D. K. Fieldhouse, The West and

the Third World: Trade, Colonialism, Dependence, and

Development (Oxford, 1999). Also see W. Baumgart, Imperialism:

The Idea and Reality of British and French Colonial Expansion,

1880--1914 (Oxford, 1982), and D. B. Abernathy, Global

Dominance: European Overseas Empires, 1415--1980 (New Haven,

Conn., 2000). On technology, see D. R. Headrick, The Tentacles

of Progress: Technology Transfer in the Age of Imperialism,

1850--1940 (Oxford, 1988). For a defense of the British imperial

mission, see N. Ferguson, Empire: The Rise and Demise of the

British World Order (New York, 2003).

Imperialist Age in Africa On the imperialist age in Africa,

above all see R. Robinson and J. Gallagher, Africa and the

Victorians: The Official Mind of Imperialism (London, 1961).

Also see B. Vandervoort, Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa,

1830--1914 (Bloomington, Ind., 1998), and two works by

T. Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa (New York, 1991) and The

Boer War (London, 1979). On southern Africa, see J. Guy, The

Destruction of the Zulu Kingdom (London, 1979), and D. Nenoon

and B. Nyeko, Southern Africa Since 1800 (London, 1984). Also

informative is R. O. Collins, ed., Historical Problems of Imperial

Africa (Princeton, N.J., 1994).

India For an overview of the British takeover and

administration of India, see S. Wolpert, A New History of India,

8th ed. (New York, 2008). C. A. Bayly, Indian Society and the

Making of the British Empire (Cambridge, 1988), is a scholarly

analysis of the impact of British conquest on the Indian economy.

Also see A. Wild’s elegant East India Company: Trade and

Conquest from 1600 (New York, 2000). For a comparative

approach, see R. Murphey, The Outsiders: The Western Experience

in China and India (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1977). In a provocative

work, Ornamentalism: How the British Saw Their Empire (Oxford,

2000), D. Cannadine argues that it was class and not race that

motivated British policy in the subcontinent.

Colonial Age in Southeast Asia General studies of the

colonial period in Southeast Asia are rare because most authors

focus on specific areas. For some stimulating essays on a variety of

aspects of the topic, see Continuity and Change in Southeast Asia:

Collected Journal Articles of Harry J. Benda (New Haven, Conn.,

1972). For an overv iew by several authors, see N. Tarling, ed., The

Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, vol. 3 (Cambridge, 1992).

Women in Africa and Asia For an introduction to the effects

of colonialism on women in Africa and Asia, see S. Hughes and

B. Hughes, Women in World History, vol. 2 (Armonk, N.Y., 1997).

Also consult the classic by E. Boserup, Women’s Role in Economic

Development (London, 1970); J. Taylor, The Social World of

Batavia (Madison, Wis., 1983); and L. Ahmed, Women and

Gender in Islam (New Haven, Conn., 1992).

The ultimate result was to deprive the colonial peoples of the right

to make their own choices about their own destiny.

The continent of Africa and southern Asia were not the only

areas of the world that were buffeted by the winds of Western

expansionism in the late nineteenth century. The nations of eastern

Asia, and those of Latin America and the Middle East as well, were

also affected in significant ways. The consequences of Western

political, economic, and military penetration varied substantially

from one region to another, however, and therefore require separate

treatment. The experience of East Asia will be dealt with in the next

chapter. That of Latin America and the Middle East will be

discussed in Chapter 24.

Visit the website for The Essential World History to access study

aids such as Flashcards, Critical Thinking Exercises, and

Chapter Quizzes:

www.cengage.com/history/duikspiel/essentialworld6e

538 CHAPTER 21 THE HIGH TIDE OF IMPERIALISM

539

CHAPTER 22

SHADOWS OVER THE PACIFIC:

EAST ASIA UNDER CHALLENGE

CHAPTER OUTLINE

AND FOCUS QUESTIONS

The Decline of the Manchus

Q

Why did the Qing dynasty decline and ultimately

collapse, and what role did the Western powers play

in this process?

Chinese Society in Transition

Q

What political, economic, and social reforms were

instituted by the Qing dynast y during its final decades,

and why were they not more successful in reversing the

decline of Manchu rule?

A Rich Country and a Strong State:

The Rise of Modern Japan

Q

To what degree was the Meiji Restoration a ‘‘revolution,’’

and to what degree did it succeed in transforming

Japan?

CRITICAL THINKING

Q

How did China and Japan each respond to Western

pressures in the nineteenth century, and what

implication did their different responses have for

each nation’s history?

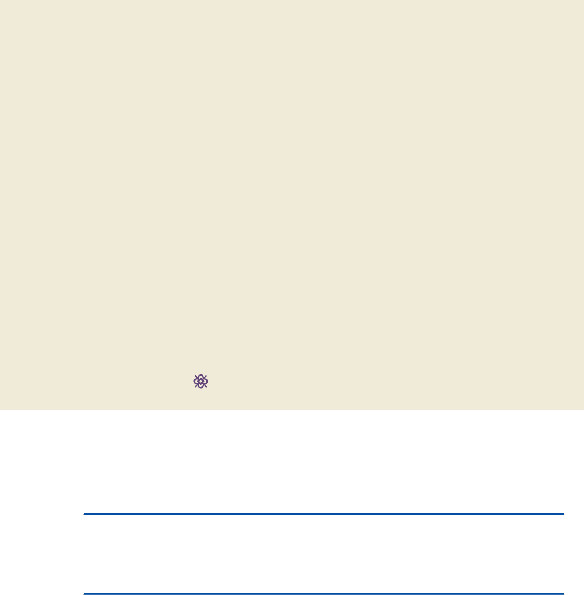

The Macartney mission to China, 1793

The Art Archive/Eileen Tweedy

540

THE BRITISH EMISSARY Lord Macartney had arrived in

Beijing in 1793 with a caravan loaded with six hundred cases of gifts

for the emperor. Flags and banners provided by the Chinese pro-

claimed in Chinese characters that the visitor was an ‘‘ambassador

bearing tribute from the country of England.’’ But the tribute was in

vain, for Macartney’s request for an increase in trade between the two

countries was flatly rejected, and he left Beijing in October with noth-

ing to show for his efforts. Not until half a century later would the

Qing dynasty---at the point of a gun---agree to the British demand for

an expansion of commercial ties.

In fact, the Chinese emperor Qianlong had responded to the

requests of his visitor with polite but poorly disguised condescension.

To Macartney’s proposal that a British ambassador be stationed in the

capital of Beijing, the emperor replied that such a request was ‘‘not in

harmony with the state system of our dynasty and will definitely not be

permitted.’’ As for the British envoy’s suggestion that regular trade rela-

tions be established between the two countries, that proposal was also

rejected. We receive all sorts of precious things, replied the Celestial

Emperor, as gifts from the myriad nations. ‘‘Consequently,’’ he added,

‘‘there is nothing we lack, as your principal envoy and others have

themselves observed. We have never set much store on strange or inge-

nious objects, nor do we need more of your country’s manufactures.’’

The Decline of the Manchus

Q

Focus Question: Why did the Qing dynasty decline

and ultimately collapse, and what role did the Western

powers play in this process?

In 1800, the Qing (Ch’ing) or Manchu dynasty was at the

height of its power. China had experienced a long period

of peace and prosperity under the rule of two great em-

perors, Kangxi and Qianlong. Its borders were secure, and

its culture and intellectual achievements were the envy of

the world. Its rulers, hidden behind the walls of the For-

bidden City in Beijing, had every reason to describe their

patrimony as the ‘‘Central Kingdom.’’ But a little over a

century later, humiliated and harassed by the black ships

and big guns of the Western powers, the Qing dynasty, the

last in a series that had endured for more than two

thousand years, collapsed in the dust (see Map 22.1).

Historians once assumed that the primary reason

for the rapid d ecline and fall of t he Manchu dynasty was

the intense pressure applied to a proud but somewhat

complacent traditional society by the modern West.

Now, however, most historians believe that internal

changes played a major role in the dynasty’s collapse

andpointoutthatatleastsomeoftheproblemssuf-

fered by the Manc hus during the nineteenth century

were self-inflicted.

Both explanations have some validity. Like so many

of its predecessors, after an extended period of growth,

the Qing dynasty began to suffer from the familiar dy-

nastic ills of official corruption, peasant unrest, and in-

competence at court. Such weaknesses were probably

exacerbated by the rapid growth in population. The long

era of peace and stability, the introduction of new crops

from the Americas, and the cultivation of new, fast-

ripening strains of rice enabled the Chinese population

to double between 1550 and 1800. The population

continued to grow, reaching the unprecedented level of

400 million by the end of the nineteenth century. Even

without the irritating presence of the Western powers, the

Manchus were probably destined to repeat the fate of

their imperial predecessors. The ships, guns, and ideas

of the foreigners simply highlighted the growing weakness

of the Manchu dynasty and likely hastened its demise. In

doing so, Western imperialism still exerted an indelible

impact on the history of modern China---but as a con-

tributing, not a causal, factor.

Opium and Rebellion

By 1800, Westerners had been in contact with China for

more than two hundred years, but after an initial period

of flourishing relations, Western traders had been limited

to a small commercial outlet at Canton. This arrangement

was not acceptable to the British, however. Not only did

they chafe at being restricted to a tiny enclave, but the

growing British appetite for Chinese tea created a severe

balance-of-payments problem. After the failure of the

Macartney mission in 1793, another mission, led by Lord

Amherst, arrived in China in 1816. But it too achieved

little except to worsen the already strained relations be-

tween the two countries. The British solution was opium.

A product more addictive than tea, opium was grown in

northeastern India and then shipped to China. Opium

had been grown in southwestern China for several hun-

dred years but had been used primarily for medicinal

purposes. Now, as imports increased, popular demand for

the product in southern China became insatiable despite

an official prohibition on its use. Soon bullion was

flowing out of the Chinese imperial treasury into the

pockets of British merchants.

The Chinese became concerned and tried to negoti-

ate. In 1839, Lin Zexu (Lin Tse-hsu; 1785--1850), a Chi-

nese official appointed by the court to curtail the opium

trade, appealed to Queen Victoria on both moral and

practical grounds and threatened to prohibit the sale of

rhubarb (widely used as a laxative in nineteenth-century

Europe) to Great Britain if she did not respond (see the

box on p. 543). But moral principles, then as now, paled

before the lure of commercial profits, and the British

continued to promote the opium trade, arguing that if the

Chinese did not want the opium, they did not have to buy

it. Lin Zexu attacked on three fronts, imposing penalties

on smokers, arresting dealers, and seizing supplies from

importers as they attempted to smuggle the drug into

China. The last tactic caused his downfall. When he

blockaded the foreign factory area in Canton to force

traders to hand over their remaining chests of opium, the

British government, claiming that it could not permit

British subjects ‘‘to be exposed to insult and injustice,’’

THE DECLINE OF THE MANCHUS 541

Historians have often viewed the failure of the Macartney

mission as a reflection of the disdain of Chinese rulers toward their

counterparts in other countries and their serene confidence in the

superiority of Chinese civilization in a world inhabited by bar bar-

ians. If that was the case, Qianlong’s confidence was misplaced, for

as the eighteenth century came to an end, the country faced a grow-

ing challenge not only from the escalating power and ambitions of

the West, but from its own growing internal weakness as well. When

insistent British demands for the right to carry out trade and mis-

sionary activities in China were rejected, Britain resorted to force

and in the Opium War, which broke out in 1839, gave Manchu

troops a sound thrashing. A humiliated China was finally forced to

open its doors.

launched a naval expedition to punish the Manchus and

force the court to open China to foreign trade.

1

The Opium War The Opium War (1839--1842) lasted

three years and demonstrated the superiority of British

firepower and military tactics (including the use of a

shallow-draft steamboat that effectively harassed Chinese

coastal defenses). British warships destroyed Chinese

coastal and river forts and seized the offshore island of

Chusan, not far from the mouth of the Yangtze River.

When a British fleet sailed virtually unopposed up the

Yangtze to Nanjing and cut off the supply of ‘‘tribute

grain’’ from southern to northern China, the Qing finally

agreed to British terms. In the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842,

the Chinese agreed to open five coastal ports to British

trade, limit tariffs on imported British goods, grant ex-

traterritorial rights to British citizens in China, and pay a

substantial indemnity to cover the costs of the war. China

also agreed to cede the island of Hong Kong (dismissed

by a senior British official as a ‘‘barren rock’’) to Great

Britain. Nothing was said in the treaty about the opium

trade, which continued unabated until it was brought

under control through Chinese government efforts in the

early twentieth century.

Although the Opium War has traditionally been

considered the beginning of modern Chinese history, it is

unlikely that many Chinese at the time would have seen it

that way. This was not the first time that a ruling dynasty

had been forced to make concessions to foreigners, and

the opening of five coastal ports to the British hardly

Aral

Sea

Lake

Balkhash

Lake

Baikal

Bay of

Bengal

South

China

Sea

East

China

Sea

Sea of Japan

(East Sea)

Pacific

Ocean

G

a

n

g

e

s

R

.

I

n

d

u

s

R

.

M

e

k

o

n

g

R

.

Y

a

n

g

t

z

e

R

.

Y

e

l

l

o

w

R

.

Urumchi

H

i

m

a

l

a

y

a

M

t

s

.

A

l

t

a

i

M

t

s

.

P

a

m

i

r

M

t

s

.

SAKHALIN

(1853–1875)

(acquired by

Russia,

1858–1860)

KOREA

JAPAN

TAIWAN

(FORMOSA)

RYUKYU

IS.

INDIA

BURMA

THAILAND

VIETNAM

CAMBODIA

PHILIPPINE

ISLANDS

TIBET

MANCHURIA

RUSSIAN EMPIRE

(acquired 1600s–1800s)

XINJIANG

MONGOLIA

KAZAKHSTAN

HINDU

KUSH

LAOS

Nanjing

Hong Kong

(Br. 1842)

Macao

(Port.)

Beijing

Tianjin

Chefoo

Port Arthur

Dairen

Vladivostok

Mukden

Lanzhou

Changsha

Wuhan

Amoy

Taipei

Fuzhou

Gobi Desert

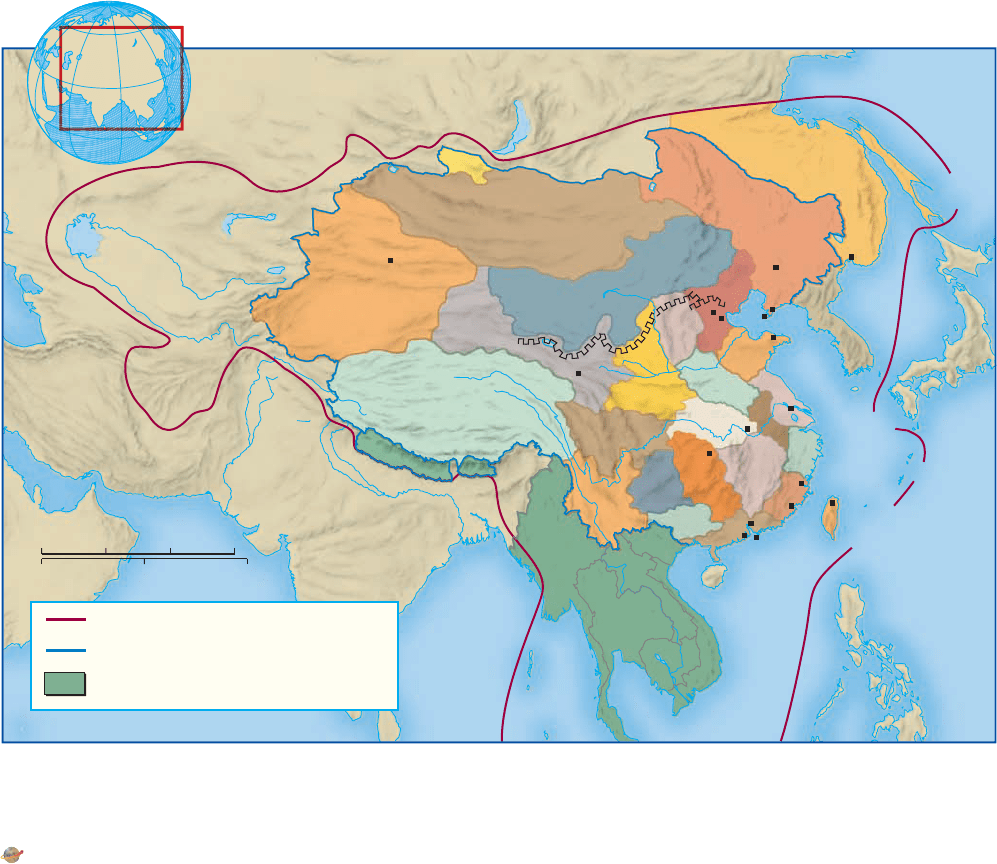

Chinese sphere of influence, 1775

Chinese Empire, 1911

Sometime tributary states to China

0 500 1,000 Miles

0 500 1,000 1,500 Kilometers

MAP 22.1 The Qin g Empire. Shown here is the Qing Empire at the height of its power in the

late eighteenth century, together with its shrunken boundaries at the moment of dissolution in 1911.

Q

How do China ’s tributary states on this map differ from those in Map 17.2? Which of

them fell under the influenc e of foreign powers during the nineteenth century?

View an animated version of this map or related maps at www.cengage.c om/history/

duikspiel/essentialworld6e

542 CHAPTER 22 SHADOWS OVER THE PACIFIC: EAST ASIA UNDER CHALLENGE

ALETTER OF ADVICE TO THE QUEEN

Lin Zexu was the Chinese imperial commissioner

in Canton at the time of the Opium War. Prior to

the conflict, he attempted to use reason and the

threat of retaliation to persuade the British to

cease importing opium illegally into southern China. The follow-

ing excerpt is from a letter that he wrote to Queen Victoria.

In it, he appeals to her conscience while showing the conde-

scension that the Chinese traditionally displayed to the rulers

of other countries.

Lin Zexu, Letter to Queen Victoria

The kings of your honorable country by a tradition handed down

from generation to generation have always been noted for their po-

liteness and submissiveness. ... Privately we are delighted with the

way in which the honorable rulers of your country deeply under-

stand the grand principles and are grateful for the Celestial grace. ...

The profit from trade has been enjoyed by them continuously for

two hundred years. This is the source from which your country has

become known for its wealth.

But after a long period of commercial intercourse, there appear

among the crowd of barbarians both good persons and bad, un-

evenly. Consequently there are those who smuggle opium to seduce

the Chinese people and so cause the spread of the poison to all

provinces. ...

The wealth of China is used to profit the barbarians. That is

to say, the great profit made by barbarians is all taken from the

rightful share of China. By what right do they then in return use

the poisonous drug to injure the Chinese people? ...Let us ask,

where is your conscience? I have heard that the smoking of opium

is very strictly forbidden by your country; that is because the harm

caused by opium is clearly understood. Since it is not permitted to

do harm to your own country, then even less should you let it be

passed on to the harm of other countries---how much less to China!

Of all that China exports to foreign countries, there is not a single

thing which is not beneficial to people. ... Is there a single article

from China which has done any harm to foreign countries? Take tea

and rhubarb, for example; the foreign countries cannot get along for

a single day without them. ... On the other hand, articles coming

from the outside to China can only be used as toys. We can take

them or get along without them. Nevertheless our Celestial Court

lets tea, silk, and other goods be shipped without limit and circu-

lated everywhere without begrudging it in the slightest. This is for

no other reason but to share the benefit with the people of the

whole world. ...

May you, O King, check your wicked and sift your vicious

people before they come to China, in order to guarantee the peace

of your nation, to show further the sincerity of your politeness and

submissiveness, and to let the two countries enjoy together the bless-

ings of peace. ... After receiving this dispatch will you immediately

give us a prompt reply regarding the details and circumstances of

your cutting off the opium traffic. Be sure not to put this off.

Q

How did the imperial commissioner seek to persuade

Queen Victoria to prohibit the sale of opium in China?

To what degree are his arguments persuasive?

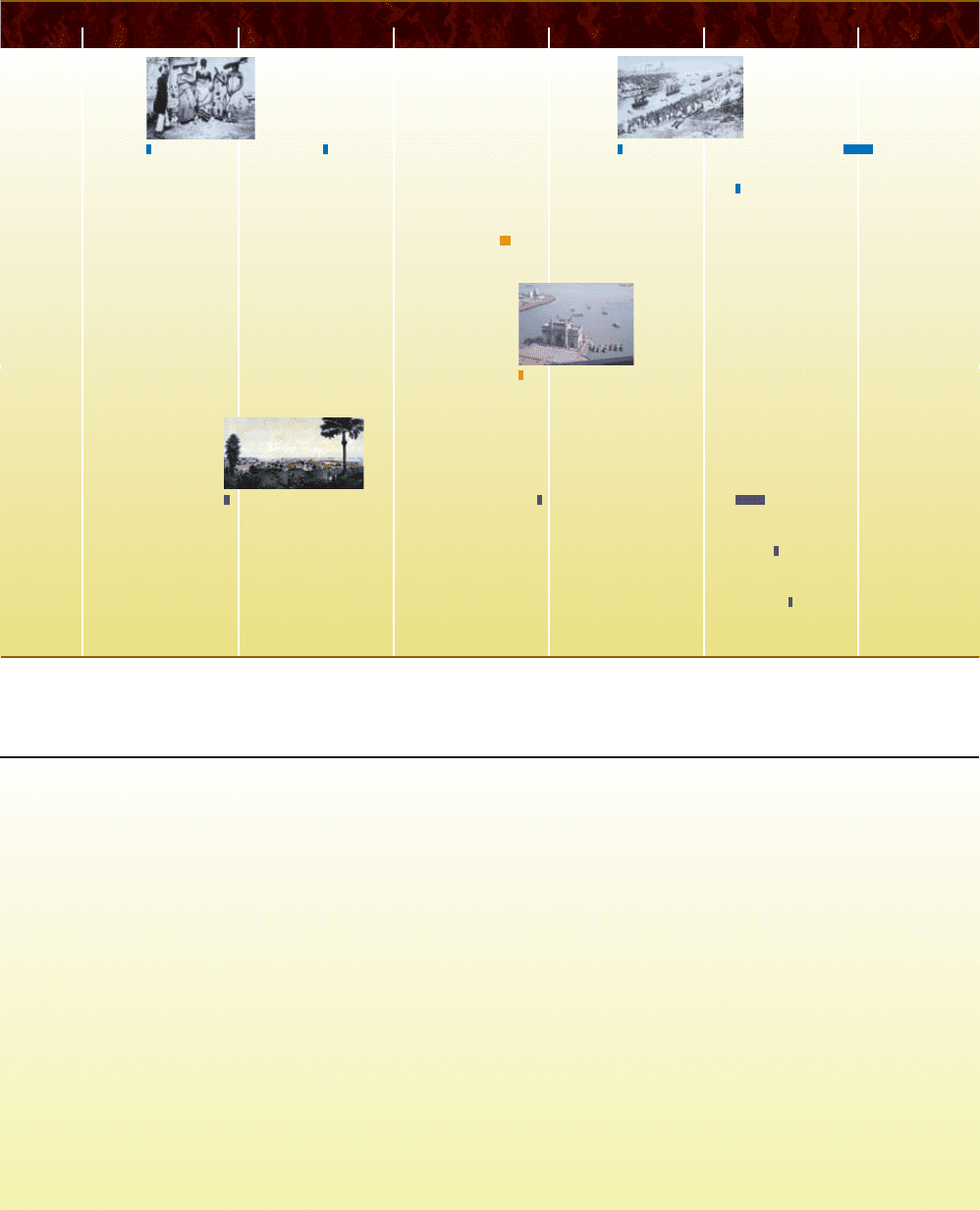

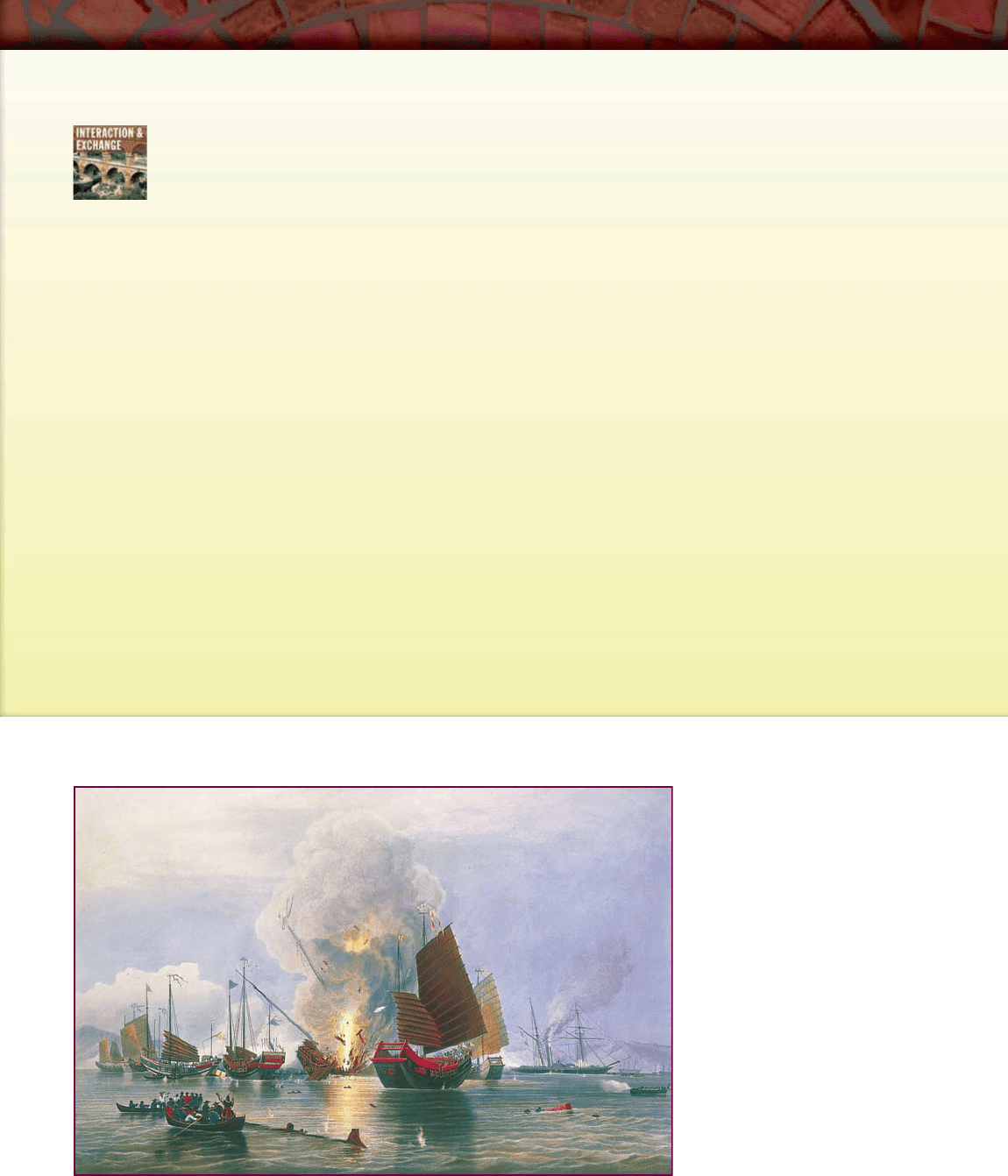

The Opium War. The Opium War,

waged between China and Great Britain

between 1839 and 1842, was China’s first

conflict with a European power. Lacking

modern military technology, the Chinese

suffered a humiliating defeat. In this

painting, heavily armed British steamships

destroy unwieldy Chinese junks along the

Chinese coast. China’s humiliation at sea

was a legacy of its rulers’ lack of interest in

maritime matters since the middle of the

fifteenth century, when Chinese junks were

among the most advanced sailing ships in

the world.

The Art Archives/Eileen Tweedy

THE DECLINE OF THE MANCHUS 543