Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Environmentally preferable purchasing

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Chase, S., ed. Defending the Earth: A Dialogue Between Murray Bookchin

and Dave Foreman. Boston: South End Press, 1991.

Devall, B., and G. Sessions. Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered.

Layton, UT: Gibbs M. Smith, 1985.

Eckersley, R. Environmentalism and Political Theory. Albany, NY: State

University of New York Press, 1992.

Naess, A. Ecology, Community and Lifestyle. New York: Cambridge Univer-

sity Press, 1989.

Worster, D. Nature’s Economy: A History of Ecological Ideas. New York:

Cambridge University Press, 1977.

Environmentally preferable

purchasing

Environmentally preferable purchasing (EPP) invokes the

practice of buying products with environmentally-sound

qualities—reduced packaging, reusability,

energy effi-

ciency

, recycled content and rebuilt or re-manufactured

products. It was first addressed officially with Executive

Order (EO) 12873 in October 1993, “Federal Acquisition,

Recycling

and Waste Prevention,” but was further enhanced

in September 14, 1998, in by EO 13101 also signed by

President Clinton. Entitled, “Greening the Government

through Waste Prevention, Recycling and Federal Acquisi-

tion,” it superseded EO 12873, but retained similar directives

for purchasing. The “Final Guidance” of directives was issued

through the

Environmental Protection Agency

in 1995.

What the federal government would adopt as a guide-

line for its purchases also would mark the beginning of

environmentally preferable purchasing for the private sector,

and create an entirely new direction for individuals and

businesses as well as governments. At the federal level, the

EPA’s “Final Guidance” was issued to apply to all acquisi-

tions, from supplies and services to buildings and systems.

It developed five “guiding principles” for incorporating the

plan into the federal government setting.

The five guiding principles are listed as follows:

O

Environment + Price + Performance = Environmentally

Preferable Purchasing

O

Pollution

prevention

O

Life cycle perspective/multiple attributes

O

Comparison of environmental impacts

O

Environmental performance information

Through its web site, in an entire section devoted to

environmentally preferable purchasing, product and service

information is provided that includes alternative fuels, build-

ings, cleaners, conferences, electronics, food serviceware, car-

pets, and copiers.

517

In the private world of business, environmentally pref-

erable purchasing has promised to save money, in addition

to meeting EPA regulations and improving employee safety

and health. In an age of

environmental liability

, EPP can

make the difference when a question of

environmental

ethics

, or damage arises.

For the private consumer, purchasing “green” in the

late 1960s and 1970s tended to mean something as simple

as recycled paper used in Christmas cards, or unbleached

natural fibers for clothing. By 2002, the average American

home is affected in countless additional ways—energy effi-

cient kitchen appliances and personal computers; environ-

mentally-sound household cleaning products; and, neigh-

borhood recycling centers. To be certified as “green” things

such as recyclability, biodegradability, organic ingredients,

and no

ozone

depleting

chemicals

are tested.

Of those everyday uses, the concern over cleaning

products for home, industrial, and commercial use has been

the focus of particular attention. Massachusetts has been

one of the state’s that has taken a lead in providing leadership

on the issue of toxic chemicals with its

Massachusetts Toxic

Use Reduction Act.

With a focus on products that have

known carcinogens and ozone-depleting substances, exces-

sive phosphate concentrations, and volatile organic com-

pounds, testing has been continued to provide alternative

products that are more environmentally acceptable—and

safer for humans and all forms of life, as well. By 2002, the

state had awarded contracts to six firms selling environmen-

tally preferred cleaning agents.

The products approved for purchasing must follow the

following mandated criteria:

O

contain no ingredients from the Massachusetts Toxic Use

Reduction Act list of chemicals

O

contain no carcinogens appearing on lists established by

the International Agency for Research on

Cancer

, the

National Toxicology Program, or the

Occupational

Safety and Health Administration

; and not contain any

chemicals defined as Class A, B. or C carcinogens by

the EPA

O

contain no ozone-depleting ingredients

O

must be compliant with the phosphate content levels stipu-

lated in Massachusetts law

O

must be compliant with the

Volatile Organic Compound

(VOC) content levels stipulated in Massachusetts law

The National Association of Counties offers an exten-

sive list of EPP resources links through its web site. In

addition to offices and agencies of the federal government,

the states of Minnesota and Massachusetts, and the local

governments of King County, Washington and Santa Mon-

ica, California, the list includes such organizations as, Buy

Green, Earth Systems’ Virtual Shopping Center for the En-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Environmentally responsible investing

vironment (an online database of recycling industry products

and services), the

Environmental Health

Coalition,

Green

Seal

, the National Institute of Government Purchasing,

Inc., and the National Pollution Prevention Roundtable.

Businesses and business-related companies mentioned in-

clude the

Chlorine

Free Products Association,

Pesticide

Action Network

of North America, Chlorine-Free Paper

Consortium, and the Smart Office Resource Center.

[Jane E. Spear]

R

ESOURCES

O

THER

Argonne National Laboratory, (U.S. Department of Energy). Green Pur-

chasing Links. [cited June 2002]. <http://www.anl.gov/P2>.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Environmentally Preferable Products Pro-

curement Program. [cited June 2002]. <http://www.state.ma.us/osd>.

Environmental Protection Agency. Environmentally Preferable Purchasing.

1998 [cited April 2002]. <http://www.epa.gov/opptintr/epp/finalguid-

ance.htm>.

National Association of Counties. Environmentally Preferred Purchasing

Resources. [cited July 2002]. <http://www.naco.org/links/env_pur.cfm>.

National Safety Council/Environmental Health Center. Environmentally

Preferable Purchasing. May 8, 2001 [June 2002]. <http://www.nsc.org/ehc>.

NYCWasteLe$$ Government. Environmentally Preferable Purchasing. Oc-

tober 2001 [June 2002]. <http://www.nycwasteless.org/gov-bus/citysense/

epp.htm>.

Ohio Environmental Protection Agency. Environmentally Preferable Pur-

chasing. [cited June 2002]. <http://www.epa.state.oh.us/opp/epp-

main.html>.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Earth Systems, 508 Dale Avenue, Charlottesville, Virginia USA 22903

434-293-2022, <http://www.earthsystems.org>

National Association of Counties, 440 First Street, NW, Washington, D.C.

USA 20001 202-393-6226, Fax: 202-393-2630, <http://www.naco.org>

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW,

Washington, D.C. USA 20460 202-260-2090, <http://www.epa.gov>

Environmentally responsible investing

Environmentally responsible investing is one component of

a larger phenomenon known as socially responsible investing.

The idea is that investors should use their money to support

industries whose operations accord with the investors’ per-

sonal ethics. This concept is not a new one. In the early

part of the century, Methodists, Presbyterians, and Baptists

shunned companies that promoted sinful activities such as

smoking, drinking, and gambling. More recently, many in-

vestors chose to protest apartheid by divesting from compa-

nies with operations in South Africa. Investors today might

arrange their investment portfolios to reflect companies’

commitment to affirmative action, human rights,

animal

rights

, the

environment

, or any other issues the investors

believe to be important.

518

The purpose of environmentally responsible investing

is to encourage companies to improve their environmental

records. The recent emergence and growth of mutual funds

identifying themselves as environmentally oriented funds

indicates that environmentally responsible investing is a pop-

ular investment area for the 1990s. In 1990, around $1 billion

were invested in environmentally oriented mutual funds.

The naming of these funds can be misleading, however.

Some funds have been developed for the purpose of being

environmentally responsible; others have been developed for

the purpose of reaping the profits anticipated to occur in

the environmental services sector as environmentalists in the

marketplace and environmental regulations encourage the

purchasing of

green products

and technology. These funds

are not necessarily environmentally responsible; some com-

panies in the environmental clean-up industry, for example,

have less than perfect environmental records.

As the idea of environmentally responsible investing

is still new, a generally accepted set of criteria for identifying

environmentally responsible companies has not yet emerged.

The fact is that everyone pollutes to some extent. The ques-

tion is where to draw the line between acceptable and unac-

ceptable behavior toward the environment.

When grading a company in terms of its behavior

toward the environment, one could use an absolute standard.

For example, one could exclude all companies that have

violated any

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA)

standards. The problem with such a standard is that some

companies that have very good overall environmental records

have sometimes failed to meet certain EPA standards. Alter-

natively, a company could be graded on its efforts to solve

environmental problems. Some investors prefer to divest of

all companies in heavily polluting industries, such as oil and

chemical companies; others might prefer to use a relative

approach and examine the environmental records of compa-

nies within industry groups. By directly comparing oil com-

panies with other oil companies, for example, one can iden-

tify the particular companies committed to improving the

environment.

For consistency, some investors might choose to divest

from all companies that supply or buy from an environmen-

tally irresponsible company. It then becomes an arbitrary

decision as to where this process stops. If taken to an extreme,

the approach rejects holding United States treasury securi-

ties, since public funds are used to support the military,

one of the world’s largest polluters and a heavy user of

nonrenewable energy.

A potential new indicator for identifying environmen-

tally responsible companies has been developed by the Coali-

tion for Environmentally Responsible Economies (CERES);

it is a code called the

Valdez Principles

. The principles are

the environmental equivalent of the Sullivan Principles, a

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ephemeral species

code of conduct for American companies operating in South

Africa. The Valdez Principles commit companies to strive

to achieve sustainable use of

natural resources

and the

reduction and safe disposal of waste. By signing the princi-

ples, companies commit themselves to continually improving

their behavior toward the environment over time. So far,

however, few companies have signed the code, possibly be-

cause it requires companies to appoint environmentalists to

their boards of directors.

As there is no generally accepted set of criteria for

identifying environmentally responsible companies, invest-

ors interested in such an investment strategy must be careful

about accepting “environmentally responsible” labels. Invest-

ors must determine their own set of screening criteria based

on their own personal beliefs about what is appropriate be-

havior with respect to the environment.

[Barbara J. Kanninen]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Brill, J. A., and A. Reder. Investing From the Heart. New York: Crown, 1992.

Harrington, J. C. Investing With Your Conscience. New York: Wiley, 1992.

P

ERIODICALS

McMurdy, D. “Green Is the Color of Money [Environmental Investing

in Canada].” Maclean’s, December 1991, 49–50.

Rauber, P. “The Stockbroker’s Smile [Environmental Sector Funds].” Sierra

75 (July-August 1990): 18–21.

Enzyme

Enzymes are catalysts, compounds (a protein) that speed up

the rate at which chemical reactions occur within living

organisms without undergoing any permanent change them-

selves. They are crucial to life since, without them, the vast

majority of biochemical reactions would occur too slowly

for organisms to survive.

In general, enzymes catalyze two quite different kinds

of reactions. The first type of reaction includes those by

which simple compounds are combined with each other to

make new tissue from which plants and animals are made.

For example, the most common enzyme in

nature

is proba-

bly carboxydismutase, the enzyme in green plants that cou-

ples

carbon dioxide

with an acceptor molecule in one step

of the

photosynthesis

process by which carbohydrates are

produced.

Enzymes also catalyze reactions by which more com-

plex compounds are broken down to provide the energy

needed by organisms. The principal digestive enzyme in the

human mouth, for example, is ptyalin (also known as a -

amylase), which begins the digestion of starch.

519

Enzymes have both beneficial and harmful effects in

the

environment

. On the one hand, environmental hazards

such as

heavy metals

, pesticides, and radiation often exert

their effects on an organism by disabling one or more of its

critical enzymes. As an example,

arsenic

is poisonous to

animals because it forms a compound with the enzyme gluta-

thione. The enzyme is disabled and prevented from carrying

out its normal function, the maintenance of healthy red

blood cells.

On the other hand, uses are now being found for

enzymes in cleaning up the environment. For example, the

Novo Nordisk company has discovered that adding an en-

zyme known as Pulpzyme can vastly reduce the amount

of

chlorine

needed to bleach wood pulp in the manufacture

of paper. Since chlorine is a serious environmental contami-

nant, this technique may represent a significant improvement

on present pulp and paper manufacturing techniques.

[David E. Newton]

EPA

see

Environmental Protection Agency

Ephemeral species

Ephemeral

species

are plants and animals whose lifespan

lasts only a few weeks or months. The most common types

of ephemeral species are

desert

annuals, plants whose seeds

remain dormant for months or years but which quickly ger-

minate, grow, and flower when rain does fall. In such cases

the amount and frequency of rainfall determine entirely how

frequently ephemerals appear and how long they last. Tiny,

usually microscopic, insects and other invertebrate animals

often appear with these desert annals, feeding on briefly

available plants, quickly reproducing, and dying in a few

weeks or less. Ephemeral ponds, short-duration desert rain

pools, are especially noted for supporting ephemeral species.

Here small insects and even amphibians have ephemeral

lives. The spadefoot toad (Scaphiopus multiplicatus), for ex-

ample, matures and breeds in as little as eight days after a

rain, feeding on short-lived brine shrimp, which in turn

consume algae and plants that live as long as water or

soil

moisture lasts. Eggs, or sometimes the larvae of these ani-

mals, then remain in the soil until the next moisture event.

Ephemerals play an important role in many plant com-

munities. In some very dry deserts, as in North Africa,

ephemeral annuals comprise the majority of living species—

although this rich

flora

can remain hidden for years at a

time. Often widespread and abundant after a rain, these

plants provide an essential food source for desert animals,

including domestic livestock. Because water is usually un-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Epidemiology

available in such environments, many desert perennials also

behave like ephemeral plants, lying dormant and looking

dead for months or years but suddenly growing and setting

seed after a rare rain fall.

The frequency of desert ephemeral recurrence depends

upon moisture availability. In the Sonoran Desert of Califor-

nia and Arizona, annual precipitation allows ephemeral

plants to reappear almost every year. In the drier deserts of

Egypt, where rain may not fall for a decade or more, dormant

seeds must survive for a much longer time before germina-

tion. In addition, seeds have highly sensitive germination

triggers. Some annuals that require at least one inch (two

to three cm) of precipitation in order to complete their life

cycle will not germinate when only one centimeter has fallen.

In such a case seed coatings may be sensitive to soil

salinity

,

which decreases as more rainfall seeps into the ground. An-

nually-recurring ephemerals often respond to temperature,

as well. In the Sonoran Desert some rain falls in both summer

and winter. Completely different summer and winter floral

communities appear in response. Such

adaptation

to differ-

ent temporal niches probably helps decrease

competition

for space and moisture and increase each species’ odds of

success.

Although they are less conspicuous, ephemeral species

also occur outside of desert environments. Short-duration

food supplies or habitable conditions in some marine envi-

ronments lead to ephemeral species growth. Ephemerals

successfully exploit such unstable environments as volcanoes

and steep slopes prone to slippage. More common are spring

ephemerals in temperate deciduous forests. For a few weeks

between snow melt and closure of the overstory canopy,

quick-growing ground plants, including small lilies and vio-

lets, sprout and take advantage of available sunshine. Flow-

ering and setting seed before they are shaded out by larger

vegetation, these ephemerals disappear by mid-summer.

Some persist in the form of underground root systems, but

others are true ephemerals, with only seeds remaining until

the next spring. See also Adaptation; Food chain/web; Op-

portunistic organism

[Mary Ann Cunningham Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Whitford, W. G. Pattern and Process in Desert Ecosystems. Albuquerque:

University of New Mexico Press, 1986.

Zahran, M. A., and A. J. Willis. The Vegetation of Egypt. London: Chapman

and Hall, 1992.

P

ERIODICALS

Hughes, J. “Effects of Removal of Co-Occurring Species on Distribution

and Abundance of Erythronium americanum (Liliaceae), a Spring Ephem-

eral.” American Journal of Botany 79 (1990): 1329–39.

520

Went, F. W. “The Ecology of Desert Plants.” Scientific American 192

(1955): 68–75.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology, the study of epidemics, is sometimes called

the medical aspect of

ecology

because it is the study of

diseases in animal populations, including humans. The epi-

demiologist is concerned with the interactions of organisms

and their environments as related to the presence of disease.

Environmental factors of disease include geographical fea-

tures,

climate

, and concentration of pathogens in

soil

and

water. Epidemiology determines the numbers of individuals

affected by a disease, the environmental circumstances under

which the disease may occur, the causative agents, and the

transmission of disease.

Epidemiology is commonly thought to be limited to

the study of infectious diseases, but that is only one aspect

of the medical specialty. The epidemiology of the

environ-

ment

and lifestyles has been studied since Hippocrates’s

time. More recently, scientists have broadened the world-

wide scope of epidemiology to studies of violence, of heart

disease due to lifestyle choices, and to the spread of disease

because of

environmental degradation

.

Epidemiologists at the Epidemic Intelligence Service

(EIS) of the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

have played important roles in landmark epidemiologic in-

vestigations. Those include the identification in 1955 of a

lot of poliovirus vaccine, supposedly dead, that was contami-

nated with live polio

virus

; an investigation of the definitive

epidemic of Legionnaires’ disease in 1976; identification

of tampons as a risk factor for toxic-shock syndrome; and

investigation of the first cluster of cases that came to be

called acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (

AIDS

). EIS

officers are increasingly involved in the investigation of non-

infectious disease problems, including the risk of injury asso-

ciated with all-terrain vehicles and cluster deaths related to

flour contaminated with parathion.

The epidemiological classification of disease deals with

the incidence, distribution, and control of disorders of a

population. Using the example of typhoid, a disease spread

through contaminated food and water, scientists first must

establish that the disease observed is truly caused by Salmo-

nella typhosa, the typhoid organism. Investigators then must

know the number of cases, whether the cases were scattered

over the course of a year or occurred within a short period,

and the geographic distribution. It is critical that the precise

locations of the diseased patients be established. In a hypo-

thetical case, two widely separated locations within a city

might be found to have clusters of cases of typhoid arising

simultaneously. It might be found that each of these clusters

revolved around a family unit, suggesting that personal rela-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Epidemiology

tionships might be important. Further investigation might

disclose that all of the infected persons had dined at one

time or at short intervals in a specific home, and that the

person who had prepared the meal had visited a rural area,

suffered a mild attack of the disease, and now was spreading

it to family and friends by unknowing contamination of food.

One very real epidemic of

cholera

in the West African

nation of Guinea-Bissau was tracked by CDC researchers us-

ing maps, interviews, and old-fashioned footwork door-to-

door through the country. An investigator eventually tracked

the source of the cholera outbreak to contaminated shellfish.

Epidemic diseases result from an ecological imbalance

of some kind. Ecological imbalance, and hence, epidemic

disease may be either naturally caused or induced by man.

A breakdown in

sanitation

in a city, for example, offers

conditions favorable for an increase in the rodent population,

with the possibility that diseases may be introduced into

and spread among the human population. In this case, an

epidemic would result as much from an alteration in the

environment as from the presence of a causative agent. For

example, an increase in the number of epidemics of viral

encephalitis, a brain disease, in man has resulted from the

ecological imbalance of mosquitoes and wild birds caused

by man’s exploitation of lowland for farming. Driven from

their natural

habitat

of reeds and rushes, the wild birds,

important natural hosts for the virus that causes the disease,

are forced to feed near farms; mosquitoes transmit the virus

from birds to cattle to man.

Lyme disease, which was tracked by epidemiologists

from man to deer to the ticks which infest deer, is directly

related to environmental changes. The lyme disease spiro-

chete probably has been infecting ticks for a long time;

museum specimens of ticks collected on Long Island in the

l940s were found to be infected. Since then, tick populations

in the Northeast have increased dramatically, triggering the

epidemic.

There are more ticks because many of the forests that

had been felled in the Northeast have returned to forestland.

Deer populations in those areas have exploded, close to

concentrated human populations, as have the numbers of

Ixodes dammini ticks which feed on deer. The deer do not

become ill, but when a tick bite infects a human host, the

result can be a devastating disease, including crippling arthri-

tis and memory loss.

Disease detectives, as epidemiologists are called, are

taking on new illnesses like heart disease and

cancer

, diseases

that develop over a lifetime. In 1948, epidemiologists en-

rolled 5,000 people in Framingham, Massachusetts, for a

study on heart disease. Every two years the subjects have

undergone physicals and answered survey questions. Epide-

miologists began to understand what factors put people at

521

risk, such as high blood pressure, elevated cholesterol levels,

smoking, and lack of exercise.

CDC epidemiologists are now tracking the pattern of

violence, traditionally a matter for police. If a pattern is

found, then young people who are at risk can be taught to

stop arguments before they escalate to violence, or public

health workers can recognize behaviors that lead to spouse

abuse, or the warning signs of teenage suicide, for example.

In the 1980s, classic epidemiology discovered that a

puzzling array of illnesses was linked, and it came to be

known as AIDS. Epidemiologists traced the disease to sexual

contact, then to contaminated blood supplies, then proved

the AIDS virus could cross the placental barrier, infecting

babies born to HIV-infected mothers.

The AIDS virus, called human immunodeficiency vi-

rus, may have existed for centuries in African monkeys and

apes. Perhaps 40 years ago, this virus crossed from monkey

to man, although researchers do not know how or why.

African

chimpanzees

can be infected with HIV, but they

don’t develop the disease, suggesting that chimps have devel-

oped protective immunity. Eventually AIDS, over centuries,

probably will develop into a less deadly disease in humans.

But before then, researchers fear that new, more deadly,

diseases will evolve.

As human communities change and create new ways

for diseases to spread, viruses and bacteria constantly evolve

as well. Rapidly increasing human populations prove a fertile

breeding ground for

microbes

, and as the planet becomes

more crowded, the distances that separate communities be-

come smaller.

Epidemiology has become one of the important sci-

ences in the study of nutritional and biotic diseases around

the world. The United Nations supports, in part, a World

Health Organization investigation of nutritional diseases.

Epidemiologists have also been called upon in times

of natural emergencies. When

Mount St. Helens

erupted

on May 18, 1980, CDC epidemiologists were asked to assist

in an epidemiologic evaluation. The agency funded and as-

sisted in a series of studies on the health effects of dust

exposure, occupational exposure, and mental health effects

of the volcanic eruption.

In 1990, CDC epidemiologists began research for the

Department of Energy to study people who have been ex-

posed to radiation. A major task of the study is to quantify

exposures based on historical reconstructions of emissions

from nuclear plant operations. Epidemiologists have under-

taken a major thyroid disease study for those people exposed

to radioactive iodine as a result of living near the

Hanford

Nuclear Reservation

in Richland, Washington, during the

l940s and l950s.

[Linda Rehkopf]

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Erodible

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Friedman, G. D. Primer of Epidemiology. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-

Hill, 1987.

Goldsmith, J. R., ed. Environmental Epidemiology: Epidemiological Investi-

gations of Community Environmental Problems. St. Louis: CRC Press, 1986.

Kopfler, F. C., and G. Craun, eds. Environmental Epidemiology. Chelsea,

MI: Lewis, 1986.

Erodible

Susceptible to

erosion

or the movement of

soil

or earth

particles due to the primary forces of wind, moving water,

ice and gravity. Tillage implements may also move soil parti-

cles, but this transport is usually not considered erosion.

Erosion

Erosion is the wearing away of the land surface by running

water, wind, ice, or other geologic agents, including such

processes as gravitational creep.

The term geologic erosion refers to the normal, natural

erosion caused by geological processes acting over long peri-

ods of time, undisturbed by humans. Accelerated erosion

is a more rapid erosion process influenced by human, or

sometimes animal, activities. Accelerated erosion in North

America has only been recorded for the past few centuries,

and in research studies, postsettlement erosion rates were

found to be eight to 350 times higher than presettlement

erosion rates.

Soil

erosion has been both accelerated and controlled

by humans since recorded history. In Asia, the Pacific, Af-

rica, and South America, complex

terracing

and other ero-

sion control systems on

arable land

go back thousands of

years. Soil erosion and the resultant decreased food supply

have been linked to the decline of historic, particularly Medi-

terranean, civilizations, though the exact relationship with

the decline of governments such as the Roman Empire is

not clear.

A number of terms have been used to describe different

types of erosion, including gully erosion, rill erosion, interrill

erosion, sheet erosion, splash erosion, saltation, surface

creep, suspension, and

siltation

. In gully erosion, water accu-

mulates in narrow channels and, over short periods, removes

the soil from this narrow area to considerable depths, ranging

from 1.5 ft (0.5 m) to as much as 82–98 ft (25–30 m).

Rill erosion refers to a process in which numerous

small channels of only a few inches in depth are formed,

usually occurring on recently cultivated soils. Interrill erosion

is the removal of a fairly uniform layer of soil on a multitude

of relatively small areas by rainfall splash and film flow.

522

Usually interpreted to include rill and interril erosion,

sheet erosion is the removal of soil from the land surface by

rainfall and surface

runoff

. Splash erosion, the detachment

and airborne movement of small soil particles, is caused by

the impact of raindrops on the soil.

Saltation is the bouncing or jumping action of soil and

mineral particles caused by wind, water, or gravity. Saltation

occurs when soil particles 0.1–0.5 mm in diameter are blown

to a height of less than 6 in (15 cm) above the soil surface

for relatively short distances. The process includes gravel or

stones effected by the energy of flowing water, as well as

any soil or mineral particle movement downslope due to

gravity.

Surface creep, which usually requires extended obser-

vation to be perceptible, is the rolling of dislodged particles

0.5–1.0 mm in diameter by wind along the soil surface.

Suspension occurs when soil particles less than 0.1 mm

diameter are blown through the air for relatively long dis-

tances, usually at a height of less than 6 in (15 cm) above

the soil surface. In siltation, decreased water speed causes

deposits water-borne sediments, or

silt

, to build up in stream

channels, lakes, reservoirs, or flood plains.

In the water erosion process, the eroded

sediment

is

often higher (enriched) in organic matter,

nitrogen

,

phos-

phorus

, and potassium than in the bulk soil from which it

came. The amount of enrichment may be related to the soil,

amount of erosion, the time of sampling within a storm,

and other factors. Likewise, during a wind erosion event,

the eroded particles are often higher in clay, organic matter,

and plant nutrients. Frequently, in the Great Plains, the

surface soil becomes increasingly more sandy over time as

wind erosion continues.

Erosion estimates using the Universal Soil Loss Equa-

tion (USLE) and the Wind Erosion Equation (WEE) esti-

mate erosion on a point basis expressed in mass per unit

area. If aggregated for a large area (e.g., state or nation),

very large numbers are generated and have been used to give

misleading conclusions. The estimates of USLE and WEE

indicate only the soil moved from a point. They do not

indicate how far the sediment moved or where it was depos-

ited. In cultivated fields, the sediment may be deposited in

other parts of the field with different crop cover or in areas

where the land slope is less. It may also be deposited in

riparian land

along stream channels or in flood plains.

Only a small fraction of the water-eroded sediment

leaves the immediate area. For example, in a study of five

river watersheds in Minnesota, it was estimated that from

less than 1–27% of the eroded material entered stream chan-

nels, depending on the soil and topographic conditions. The

deposition of wind-eroded sediment is not well quantified,

but much of the sediment is probably deposited in nearby

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Escherichia coli

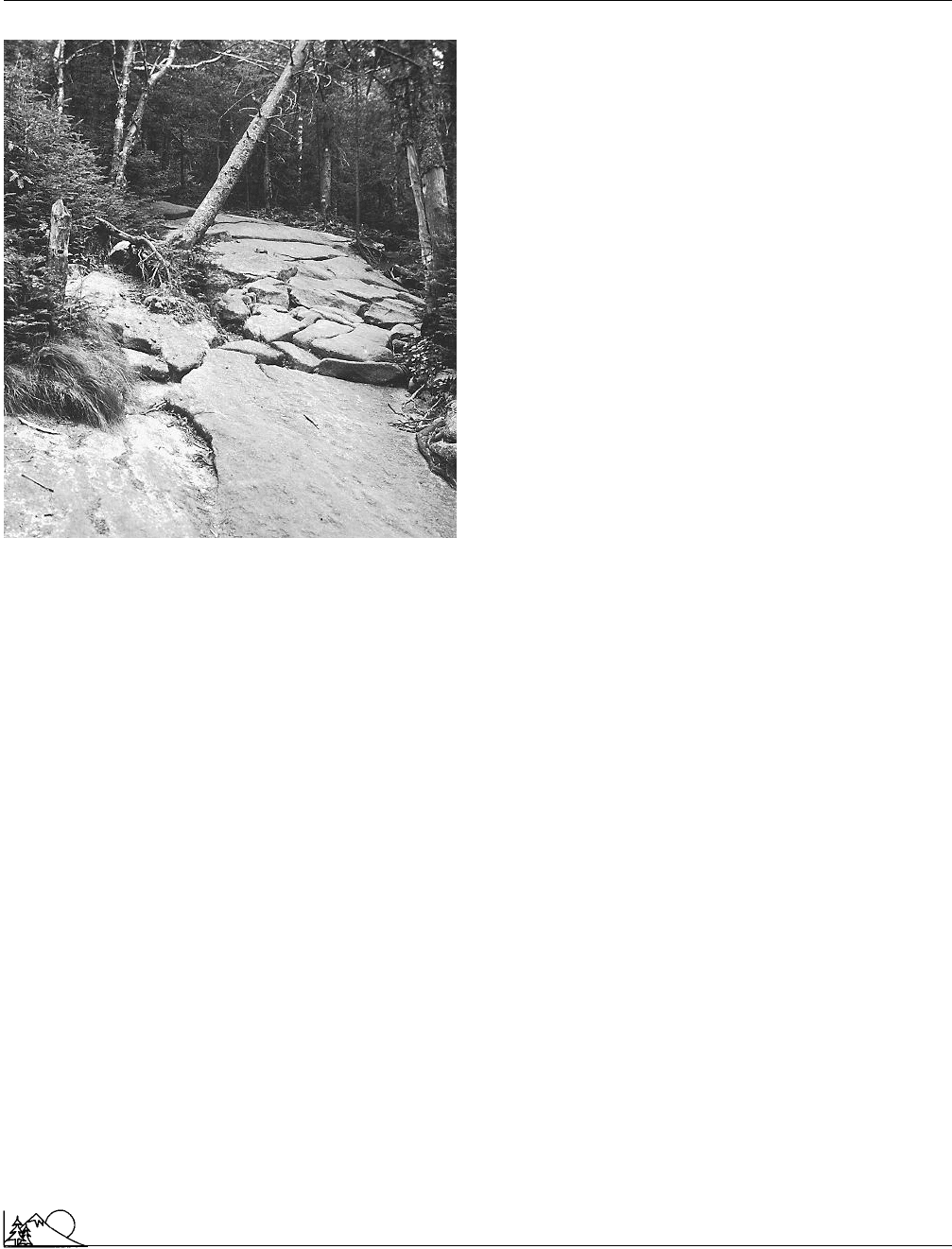

Soil erosion on a trail in the Adirondack Moun-

tains (Photograph by Yoav Levy. Phototake. Reproduced

by permission.)

areas more protected from the wind by vegetative cover,

stream valleys, road ditches, woodlands, or farmsteads.

While a number of national and regional erosion esti-

mates for the United States have been made since the 1920s,

the methodologies of estimation and interpretations have

been different, making accurate time comparisons impossi-

ble. The most extensive surveys have been made since the

Soil, Water and Related Resources Act was passed in 1977.

In these surveys a large number of points were randomly

selected, data assembled for the points, and the Universal

Soil Loss Equation (USLE) or the Wind Erosion Equation

(WEE) used to estimate erosion amounts. While these equa-

tions were the best available at the time, their results are

only estimations, and subject to interpretation. Considerable

research on improved methods of estimation is underway

by the

U.S. Department of Agriculture

.

In the cornbelt of the United States, water erosion

may cause a 1.7–7.8% drop in soil productivity over the next

one hundred years, as compared to current levels, depending

on the

topography

and soils of the area. The U.S.D.A.

results, based on estimated erosion amounts for 1977, only

included sheet erosion, not losses of plant nutrients. Though

the figures may be low for this reason, other surveys have

produced similar estimates.

523

In addition to depleting farmlands, eroded sediment

causes off-site damages that, according to one study, may

exceed on-site loss. The sediment may end up in a domestic

water supply, clog stream channels, even degrade

wetlands

,

wildlife

habitats, and entire ecosystems. See also Environ-

mental degradation; Gillied land; Soil eluviation; Soil or-

ganic matter; Soil texture

[William E. Larson]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Paddock, J. N., and C. Bly. Soil and Survival: Land Stewardship and the

Future of American Agriculture. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1987.

Resource Conservation Glossary. 3rd ed. Ankeny, IA: Soil Conservation

Society of America, 1982.

P

ERIODICALS

Steinhart, P. “The Edge Gets Thinner.” Audubon 85 (November 1983):

94–106+.

O

THER

Brown, L. R., and E. Wolf. “Soil Erosion: Quiet Crisis in the World

Economy.” Worldwatch Paper #60. Washington DC: Worldwatch Insti-

tute, 1984.

Escherichia coli

Escherichia coli,orE. coli is a bacterium in the family Entero-

bacteriaceae that is found in the intestines of warm-blooded

animals, including humans. E. coli represent about 0.1% of

the total bacteria of an adult’s intestines (on a Western diet).

As part of the normal

flora

of the human intestinal tract,

E. coli aids in food digestion by producing vitamin K and

B-complex vitamins from undigested materials in the large

intestine and suppresses the growth of harmful bacterial

species

. However, E. coli has also been linked to diseases

in about every part of the body. Pathogenic strains of E. coli

have been shown to cause pneumonia, urinary tract infec-

tions, wound and blood infections, and meningitis.

Toxin-producing strains of E. coli can cause severe

gastroenteritis (hemorrhagic colitis), which can include ab-

dominal pain, vomiting, and bloody diarrhea. In most peo-

ple, the vomiting and diarrhea stop within two to three days.

However, about 5–10% of the those affected will develop

hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS), which is a rare condi-

tion that affects mostly children under the age of 10, but

also may affect the elderly as well as persons with other

illnesses. About 75% of HUS cases in the United States are

caused by an enterohemorrhagic (intestinally-related orga-

nism that causes hemorrhaging) strain of E. coli referred to

as E. coli O157:H7, while the remaining cases are caused by

non-O157 strains. E. coli. O157:H7 is found in the intestinal

tract of cattle. In the United States, the

Centers for Disease

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Escherichia coli

Control and Prevention

estimates that there are about

10,000–20,000 infections and 500 deaths annually that are

caused by E. coli O157:H7.

E. coli O157:H7, first identified in 1982, and isolated

with increasing frequency since then, is found in contami-

nated foods such as meat, dairy products, and juices. Symp-

toms of an E. coli O157:H7 infection start about seven days

after infection with the bacteria. The first symptom is sudden

onset of severe abdominal cramps. After a few hours, watery

diarrhea begins, causing lose of fluids and electrolytes (dehy-

dration), which causes the person to feel tired and ill. The

watery diarrhea lasts for about a day, and then changes to

bright red bloody stools, as the infection causes sores to form

in the intestines. The bloody diarrhea lasts for two to five

days, with as many as 10 bowel movements a day. Additional

symptoms may include nausea and vomiting, without a fever,

or with only a mild fever. After about five to 10 days, HUS

can develop. HUS is characterized by destruction of red

blood cells, damage to the lining of blood vessel walls, re-

duced urine production, and in severe cases, kidney failure.

Toxins

produced by the bacteria enter the blood stream,

where they destroy red blood cells and platelets, which con-

tribute to the clotting of blood. The damaged red blood

cells and platelets clog tiny blood vessels in the kidneys, or

cause lesions to form in the kidneys, making it difficult for

the kidneys to remove wastes and extra fluid from the body,

resulting in hypertension, fluid accumulation, and reduced

production of urine. The diagnosis of an E. coli infection is

made through a stool culture.

Treatment of HUS is supportive, with particular atten-

tion to management of fluids and electrolytes. Some studies

have shown that the use of antibiotics and antimotility agents

during an E. coli infection may worsen the course of the

infection and should be avoided. Ninety percent of children

with HUS who receive careful supportive care survive the

initial acute stages of the condition, with most having no

long-term effects. In about 50% of the cases, short term

replacement of kidney function is required in the form of

dialysis. However, between 10 and 30% of the survivors

will have kidney damage that will lead to kidney failure

immediately or within several years. These children with

kidney failure require on-going dialysis to remove wastes

and extra fluids from their bodies, or may require a kidney

transplant.

The most common way an E. coli O157:H7 infection

is contracted is through the consumption of undercooked

ground beef (e.g., eating hamburgers that are still pink in-

side). Healthy cattle carry E. coli within their intestines.

During the slaughtering process, the meat can become con-

taminated with the E. coli from the intestines. When con-

taminated beef is ground up, the E. coli bacteria are spread

throughout the meat. Additional ways to contract an E. coli

524

infection include drinking contaminated water and unpas-

teurized milk and juices, eating contaminated fruits and

vegetables, and working with cattle. The infection is also

easily transmitted from an infected person to others in set-

tings such as day care centers and nursing homes when

improper sanitary practices are used.

Prevention of HUS caused by ingestion of foods con-

taminated with E. coli O157:H7 and other toxin-producing

bacteria is accomplished through practicing hygienic food

preparation techniques, including adequate hand washing,

cooking of meat thoroughly, defrosting meats safely, vigor-

ous washing of fruits and vegetables, and handling leftovers

properly. Irradiation of meat has been approved by the

United States

Food and Drug Administration

and the

United States Department of Agriculture in order to decrease

bacterial contamination of consumer meat supplies.

The presence of E. coli in surface waters indicates that

there has been fecal contamination of the water body from

agricultural and/or urban and residential areas. However,

the contribution from human vs. agricultural sources is diffi-

cult to determine. Since the concentration of E. coli in a

surface water body is dependent on

runoff

from various

sources of contamination, it is related to the

land use

and

hydrology

of the surrounding

watershed

. E. coli concen-

trations at a specific location in a water body will vary de-

pending on the bacteria levels already in the water, inputs

from various sources, dilution with precipitation and runoff,

and

die-off

or multiplication of the organism within the

water body. Sediments can act as a

reservoir

for E. coli,as

the sediments protect the organisms from bacteriophages

and microbial toxicants. The E. coli can persist in the sedi-

ments and contribute to concentrations in the overlying wa-

ters for months after the initial contamination.

Routine monitoring for enteropathogens, which cause

gastrointestinal diseases and are a result of fecal contamina-

tion, is necessary to maintain water that is safe for drinking

and swimming. Many of these organisms are hard to detect,

so monitoring of an

indicator organism

is used to determine

fecalcontamination. To provide safedrinking water, the water

istreated with

chlorine

, ultra-violetlight, and/or

ozone

.Tra-

ditionally fecal

coliform bacteria

have been used as the indi-

cator organisms for monitoring, but the test for these bacteria

also detects thermotolerant non-fecal coliform bacteria.

Therefore, the U.S.

Environmental Protection

Agency

(EPA) is recommending that E. coli as well as

enterococci be used as indicators of fecal contamination of

a water body instead of fecal coliform bacteria. The test for

E. coli does not include non-fecal thermotolerant coliforms.

An epidemiological study has shown that even though the

strains of E. coli present in a water body may not be patho-

genic, these organisms are the best predictor of swimming-

associated gastrointestinal illness.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Essential fish habitat

The U.S. EPA recreational

water quality

standard

is based on a threshold concentration of E. coli above which

the health risk from waterborne disease is unacceptably high.

The recommended standard corresponds to approximately

8 gastrointestinal illnesses per 1000 swimmers. The standard

is based on two criteria: 1) a geometric mean of 126 organ-

isms per 100 ml, based on several samples collected during

dry weather conditions, or 2) 235 organisms/100 ml sample

for any single water sample. During 2002, the U.S. EPA

finalized guidance on the use of E. coli as the basis for

bacterial water quality criteria to protect recreational fresh-

water bodies.

[Judith L. Sims]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Bell, Chris, and Alec Kyriakides. E. coli. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall,

1998.

Burke, Brenda Lee. Don’t Drink the Water: The Waterton Tragedy. Victoria,

BC: Trafford Publishing, 2001.

Parry, Sharon, and S. Palmer. E. coli: Environmental Health Issues of Vtec

0157. London, UK:Spon Press, 2001.

Sussman, Max, ed. Escherichia coli: Mechanisms of Virulence. Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Implementation Guidance for Ambi-

ent Water Quality Criteria for Bacteria. Draft, EPA-823-B-02-003. Wash-

ington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2002.

P

ERIODICALS

Koutkia, Polyxeni, Eleftherios Mylonakis, and Timothy Flanigan. “Entero-

hemorrhagic Escherichia coli: An Emerging Pathogen.” American Family

Physician, 56, no. 3 (September 1, 1997): 853–858.

O

THER

“Escherichia coli and Recreational Water Quality in Vermont.” Bacterial

Water Quality. February 7, 2000 [June 2002]. <http://snr.uvm.edu/www/

pc/sal/ecoli/index.htm>.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. “Escherichia coli.” Bad Bug Book.

February 13, 2002 [cited May 25, 2002]. <http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~mow/

chap15.html>.

Essential fish habitat

Essential Fish Habitat (EFH) is a federal provision to con-

serve and sustain the habitats that fish need to go through

their life cycles. The United States Congress in 1996 added

the EFH provision to the Magnuson Fishery

Conservation

and Management Act of 1976. Renamed the Magnuson-

Stevens Conservation and Management Act in 1996, the

act is the federal law that governs marine (sea) fishery man-

agement in the United States.

The amended act required that fishery management

plans include designations and descriptions of essential fish

habitats. The plan is a document describing the strategy to

reach management goals in a fishery, an area where fish

525

breed and people catch them. The Magnuson-Stevens Act

covers plans for waters located within the United States’

exclusive economic zone

. The zone extends offshore from

the coastland for three to 200 miles.

The designation of EFH was necessary because the

continuing loss of aquatic

habitat

posed a major longterm

threat to the viability of commercial and recreational fisher-

ies, Congress said in 1996. Lawmakers defined EFH as

“those waters and substrate necessary to the fish for spawn-

ing, breeding, feeding, or growth to maturity". Substrate

consists of

sediment

and structures below the water.

The Magnuson-Stevens Act called for identification

of EFH by eight regional fishery management councils and

the Highly Migratory Species Division of the National Ma-

rine Fisheries Service (NMFS), an agency of the Commerce

Department’s

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Ad-

ministration

(NOAA). Under the Magnuson-Stevens Act,

NOAA manages more than 700

species

. These species

range from tiny reef fish to large tuna.

NOAA Fisheries and the councils are required by the

act to minimize “to the extent practicable” the adverse effects

of fishing on EFH. The act also directed the councils and

NOAA to devise plans to conserve and enhance EFH. Those

plans are included in the management plans. Also in the

plan are “habitat areas of particular concern.” These areas

within an EFH include rare habitat or habitat that is ecologi-

cally important.

Furthermore, the act required federal agencies to work

with NMFS when the agencies plan to authorize, finance,

or carry out activities that could adversely affect EFH. This

process called an EFH consultation is required if the agency

plans an activity like

dredging

near an essential fishing

habitat. While NMFS does not have veto power over the

project, NOAA Fisheries will provide conservation recom-

mendations.

The eight regional fishery management councils were

established by the 1976 Magnuson Fishery and Conservation

Management Act. That legislation also established the ex-

clusive economic zone and staked the United States’ claim

to it. The 1976 act also addressed issues such as foreign

fishing and how to connect the fishing community to the

management process, according to an NOAA report. The

councils manage living marine resources in their regions and

address issues such as EFH.

The New England Fishery Management Council

manages fisheries in federal waters off the coasts of Maine,

New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Con-

necticut. New England fish species include Atlantic cod,

Atlantic halibut, and white hake.

The Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council

manages fisheries in federal waters off the mid-Atlantic

coast. Council members represent the states of New York,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Estuary

New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Vir-

ginia. North Carolina is represented on this council and the

South Atlantic Council. Fish species found within this re-

gion include ocean quahog, Atlantic mackerel, and but-

terfish.

The South Atlantic Fishery Management Council is

responsible for the management of fisheries in the federal

waters within a 200-mile area off the coasts of North Caro-

lina, South Carolina, Georgia, and east Florida to Key West.

Marine species in this area include cobia, golden crab, and

Spanish mackerel.

The Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council

draws its membership from the Gulf Coast states of Florida,

Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. Marine species

in this area include shrimp, red drum, and stone crab.

The Caribbean Fishery Management Council man-

ages fisheries in federal waters off the Commonwealth of

Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The management

plan covers coral reefs and species including queen triggerfish

and spiny lobster.

The North Pacific Fishery Management Council in-

cludes representatives from Alaska and Washington state.

Species within this area include

salmon

, scallops, and

king crab.

The Pacific Fishery Management Council draws its

members from Washington, Oregon, and California. Spe-

cies in this region include salmon, northern anchovy, and

Pacific bonito.

The Western Pacific Fishery Management Council is

concerned with the United States exclusive economic zone

that surrounds Hawaii, American Samoa, Guam, the North-

ern Mariana Islands, and other U.S. possessions in the Pa-

cific. Fishery management encompasses coral and species

such as

swordfish

and striped marlin.

[Liz Swain]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Dobbs, David. The Great Gulf: Fishermen, Scientists, and the Struggle to

Revive the World’s Greatest Fishery. Washington, DC: Island Press, 2000.

Hanna, Susan. Fishing Grounds: Defining a New Era for American Fishing

Management. Washington, DC: Island Press, 2000.

O

RGANIZATIONS

National Marine Fisheries Service Office of Habitat Conservation, 1315

E. West Highway, 15th Floor, Silver Springs, MD 20910 (301) 713-

2325, Fax: (301) 713-1043, Email: cyber.fish@noaa.gov, http://

www.nmfs.noaa.gov

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 14th Street &

Constitution Avenue, NW, Room 6013, Washington, D.C. 20230 (202)

482-6090, Fax: (202) 482-3154, Email: answers@noaa.gov, http://

www.noaa.gov

526

Estuary

Estuaries represent one of the most biologically productive

aquatic ecosystems on Earth. An estuary is a coastal body

of water where chemical and physical conditions modulate

in an intermediate range between the freshwater rivers that

feed into them and the salt water of the ocean beyond them.

It is the point of mixture for these two very different aquatic

ecosystems. The freshwater of the rivers mix with the salt

water pushed by the incoming tides to provide a

brackish

water

habitat

ideally suited to a tremendous diversity of

coastal marine life.

Estuaries are nursery grounds for the developing young

of commercially important fish and shellfish. The young of

any

species

are less tolerant of physical extremes in their

environment

than adults. Many species of marine life can-

not tolerate the concentrations of salt in ocean water as they

develop from egg to subadult, and by providing a mixture

of fresh and salt water, estuaries give these larval life forms

a more moderate environment in which to grow. Because

of this, the adults often move directly into estuaries to spawn.

Estuaries are extremely rich in nutrients, and this is

another reason for the great diversity of organisms in these

ecosystems. The flow of freshwater and the periodic

flood-

ing

of surrounding marshlands provides an influx of nutri-

ents, as does the daily surges of tidal fluctuations. Constant

physical movement in this environment keeps valuable

nutri-

ent

resources available to all levels within the

food

chain/web

.

Coastal estuaries also provide a major

filtration

system

for waterborne pollutants. This natural

water treatment

facility helps maintain and protect

water quality

, and stud-

ies have shown that one acre of tidal estuary can be the

equivalent of a $75,000 waste treatment plant. When its

value for

recreation

and seafood production are included

in this estimate, a single acre of estuary has been valued at

$83,000. An acre of farmland in America’s Corn Belt, for

comparison, has a top value of $1,200 and an annual income

through crop production of $600.

Throughout the ages man has settled near bodies of

water and utilized the bounty they provide, and the economic

value of estuaries, as well as the fact that they are a coastal

habitat, has made them vulnerable to exploitation.

Chesa-

peake Bay

on the Atlantic coast is the largest estuary in

the United States, draining six states and the District of

Columbia. It is the largest producer of oysters in the country;

it is the single largest producer of blue crabs in the world,

and 90 percent of the striped bass found on the East Coast

hatch there. It one of the most productive estuaries in the

world, yet its productivity has declined in recent decades

due to a huge increase in the number of people in the region.

Between the 1940s and the 1990s, the population jumped