Fattah H., Caso F. A Brief History Of Iraq

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

22

23

IRAQ, THE FIRST SOCIETY

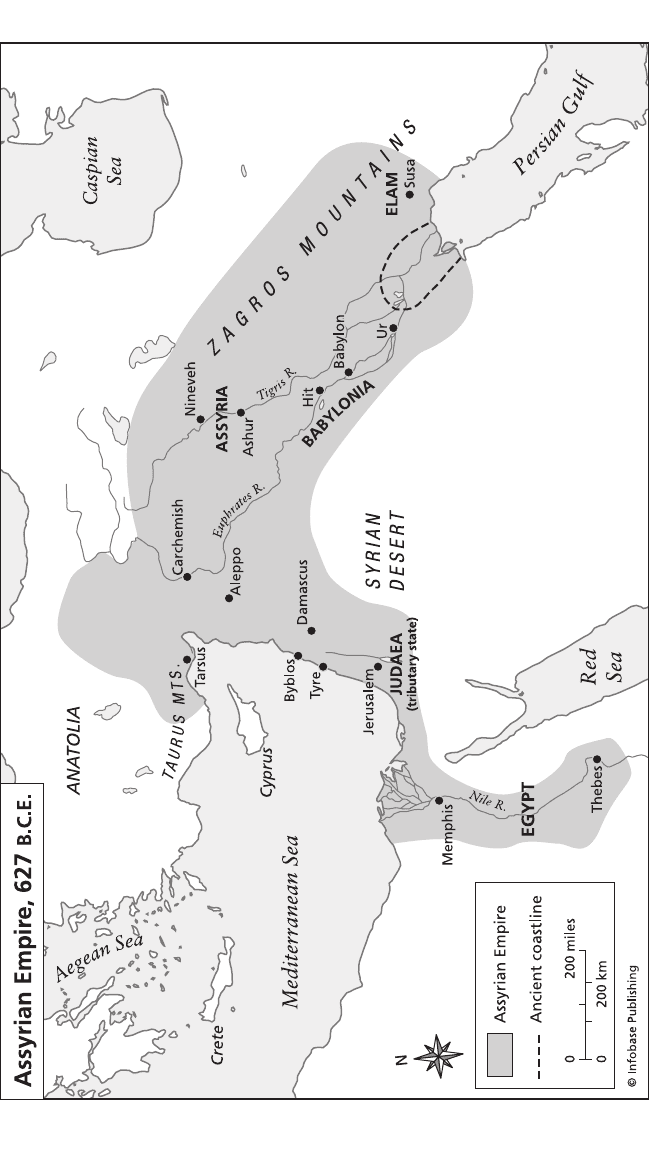

lands lost, either in the south or the west. Oppenheim has made a pro-

vocative case for the relentless Assyrian compulsion to go to war. He

believes that the Assyrians periodically created and re-created “ephem-

eral empires” (Oppenheim 1977, 167) that rarely outlasted a particular

Assyrian king’s reign because of two main reasons: the instability of the

Assyrian system of government and the collapse of the economic rev-

enues available to Assyrian rulers within the core territories. Certainly,

evidence suggests that the tightly centralized inner domain (Ashur) was

always under pressure to produce a surplus to meet taxes. Obviously,

one of the calculations of Assyrian generals was that a wider empire

would extend revenue fl ows. But Oppenheim speculates that the almost

automatic imperative to “restore” the greater empire may also have

sprung from protonationalist ideals on the part of a select Assyrian rul-

ing clique who wanted to enlarge the homeland for ideological (that is,

religious) reasons. In other words, in order to appease the gods as well

as to actualize an “Assyrian” identity, more tribute-bearing lands would

have to be joined to the Assyrian center. Of course, on a more mundane

level, it is undeniable that the Assyrian campaigns were also launched

as defensive wars, to secure the always troublesome outermost borders

of the empire and to keep open vital trade routes from northern Iraq to

Syria, Anatolia, Iran, and the Gulf.

Alongside issues of war and peace, the Assyrians may also have inno-

vated mass deportation campaigns. History relates that Tiglath-pileser

III (r. 744–727

B.C.E.) was particularly well known for employing this

strategy. According to Roux, “[W]hole towns and districts were emptied

of their inhabitants, who were resettled in distant regions and replaced

by people brought in force from other countries. In 742 and 741

B.C.E.,

for instance, 30,000 Syrians from the region of Hama were sent to the

Zagros mountains, while 18,000 Arameans from the left bank of the

Tigris were transferred to northern Syria” (Roux 1992, 307).

The other famous example is that of Sargon II (r. 721–705

B.C.E.),

who vigorously dispersed the Hebrews after the conquest of the north-

ern kingdom of Israel (after having made them pay taxes, as Assyrian

kings did with all occupied peoples). Referred to as the dispersion of

the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, this mass deportation was perfectly in

line with Assyrian practice (deportation measures were carried out as

far south as Arabia). Deportations occurred for a number of reasons.

Assyrian commanders, always anxious to maximize imperial gain,

either transported farmers and laborers from one overpopulated area to

a less productive district and made the deportees grow crops deemed

necessary for the empire or pressed the deportees in the army, or even

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

24

forced them to relocate to less-developed areas where crafts and indus-

tries were absent. The point, crudely made by these forced migrations,

was that Assyrian authorities would not rest until Greater Assyria

became completely self-suffi cient in terms of people and resources, and

the internal distribution of specializations and services was rationalized

to create a rough equity, if not for the Assyrians at large, then at least

for the elite that ran the empire.

In sum, even though the Assyrians followed the tradition of earlier

civilizations and built institutions that infl uenced the region for centu-

ries to come, their innovations and adaptations are always deemed sec-

ondary to the more celebrated exploits of boots on the ground. And yet,

most Assyrian kings, for example, were avid builders: Ashurnasirpal II

constructed a great palace complex close to the Tigris River and Upper

Zab tributary in northern Iraq; eventually the site took on the name of

Nimrud (originally, Kalkh). Nimrud, south of present-day Mosul, has

been the scene of excavations for more than 150 years by the British,

Poles, Italians, Americans, and of course, Iraqis. Its site is now so well

known that archaeologists can confi dently list four important palaces,

three smaller ones, “perhaps fi ve temples, three gates, a ziggurat or

temple tower of Ninurta, the patron god of the city, and six townhouses,

all dating to the period of the Assyrian Empire” (Paley 2003, 1). After

the coalition attack on Baghdad in 2003, a National Geographic team

drained the underground fl oors of a Baghdad bank to fi nd the vast

treasure of one of Ashurnasirpal’s palaces. The bank’s vaults had been

plunged underwater in the war’s chaotic aftermath.

The ruler Sargon II, who succeeded Ashurnasirpal II, built an entire

town in Khorsabad (Dar-Shrukin). Khorsabad had a square plan and

was defended by statues of bull-men erected at the seven major gates.

The palace, situated in the inner sanctum of the city, was built on a

raised platform and had 300 rooms and 30 courtyards and a ziggurat

of many different hues. But Sargon did not live long enough to take

pleasure in his new town: One year after Khorsabad was completed, he

was killed in battle, after which the Assyrian ruling house retreated to

Nineveh, ancient capital of Ashur.

Even Sennacherib (r. 705–681

B.C.E.), famous for destroying Babylon,

built temples and palaces and started massive public works to restore

agricultural prosperity to the empire. Nineveh became the spacious,

fortifi ed capital of the Assyrian Empire with a great exterior wall, the

remains of which still occupy the left bank of the Tigris, opposite pres-

ent-day Mosul. A splendid palace guarded by statues of bronze lions

and surrounded by a landscaped garden, watered by an aqueduct built

25

IRAQ, THE FIRST SOCIETY

specially for that purpose, completed the lavish picture. Esarhaddon (r.

680–669

B.C.E.), Sennacherib’s son, rebuilt Babylon, which his father

had razed to the ground because of Babylonian “perfi dy,” and by 669

B.C.E., Assyria’s southern province had taken on all the magnifi cence of

the old.

The Spread of Tribal Movements

The cities and empires that ruled Iraq and battled each other for domi-

nation also constantly fought to extend their sway over the nomadic

peoples who lived on the margins of urban settlements and whose

histories are, for the most part, unwritten (except by their enemies)

and therefore all the more obscure. Geography truly determined des-

tiny in ancient Iraq; the same patterns were repeated over and over

again for thousands of years and all the way into the premodern era,

with the eruption of nomadic pastoralists emerging out of the Arabian

Peninsula, the settlement of tribal peoples on the fringes of civilization

in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen, and their eventual defeat and incorporation

into the larger empires. The fact that city folk were once nomadic pas-

toralists or seminomads themselves only tends to blur the boundaries

between cities, empires, and tribes. The cycle of nomads settling down

to form or join already established cities and then blending into larger

formations such as empires, only to return to a pastoralist mode once

these larger formations disappear, is a familiar one in the Middle East.

It is best described by a 14th-century Muslim historian, Ibn Khaldun,

the famous author of al-Muqadimma (Prolegomena). In that work, Ibn

Khaldun described the “natural life of empires” as having three stages,

basically corresponding to generations in which the nomadic (or, for

modern empires, rural) life gives way to the settled, or urban, life. In

the fi nal stage, the nomadic life is completely forgotten, and decadence

sets in.

The domestication of the camel (2000–1300

B.C.E.), allowed the

Arabs to become more mobile, and they started to penetrate into the

more prosperous regions of the Middle East. In the ninth century

B.C.E., we fi rst begin to hear of the Arabs, a term usually glossed over

by archaeologists and historians until the dawn of the Islamic era. And

yet, 15 centuries before the rise of Islam, the word Arab appears on clay

tablets in the Assyrian period, starting from the reign of Shalmaneser III

onward (Gailani and Alusi 1999, 9–14). Referring both to the Arabian

Peninsula, as well as to a distinct category of people under a variety

of names, such as Arubu or Amel-Ur-bi, the term has generally been

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

26

suspended in favor of broader categories, such as “the Semites,” which

came to include not only the Arabs but the Aramaeans and Canaanites

as well.

Of nomadic origins but from different regions of the eastern

Mediterranean, both the Aramaeans and the Arabs turned to trade once

they had crossed into greener Syrian pastures, while the Canaanites, the

best-known traders of the region, made Palestine their home. In north

Syria, the largest group, the Aramaeans overwhelmed earlier civiliza-

tions and took over their cities, eventually subordinating the mega-

lopolis of Aram-Damascus to their growing empire. Equally important

was another community, the Chaldeans, who lived in the marshes of

southernmost Iraq. The Chaldeans spoke a dialect of Aramaic but they

were a distinct group of peoples. Like the Aramaeans and Arabs at an

earlier stage, the Chaldeans were divided into several different regions,

each ruled by a tribal chief. They grew dates, subsisted on fi shing, and

bred horses. The Chaldeans, just like the Arabs and the Arameans, prof-

ited from the overland trade passing by way of Arabia to northern Syria.

Fortune was only to smile on the former group, in 626

B.C.E., when the

fl uctuating military and political developments of the period brought

forth the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

The Neo-Babylonian Empire (625–539 B.C.E.)

After several centuries of eclipse, the Babylonian dynasty rose again.

Under the Chaldean Nabu-apla-usur (Nabopolassar, r. ca. 625–605

B.C.E.), Babylonia invaded and conquered the provinces of the

Assyrian Empire from the Mediterranean Sea to the Arabian Gulf. The

three main Assyrian cities, Ashur, Nineveh, and Nimrud, were devas-

tated by fi re and were left in ruins. Assyria was obliterated from the

map. After the decline of Assyria, Babylonia and Egypt were the only

large empires facing each other in Syria-Palestine. The Babylonian

troops were commanded by Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562

B.C.E.),

who was married to Amyitis, the daughter of the king of the power-

ful Medes, located in what is now northern Iraq, and thus Babylonia

was protected by its alliance with the Medes against the forces

beyond the kingdom. After the death of his father, Nabu-apla-usur,

Nebuchadnezzar became king and began a long war to conquer the

kingdom of Judah and its capital, Jerusalem. In 586

B.C.E., the city

fell. When Nebuchadnezzar’s appointee in Jerusalem, Zedekiah, tried

to turn the tables on his master and make himself the actual ruler

of the province, the Babylonian king used the time-honored tactic

27

IRAQ, THE FIRST SOCIETY

of deporting approximately 3,000 of Judah’s Jews as punishment.

Zedekiah attempted a revolt but was defeated; he was brought before

Nebuchadnezzar and, after witnessing the execution of his sons, had

his eyes gouged out.

After Nebuchadnezzar’s death, Babylonia experienced a period of

misrule and assassination. Three kings ruled during the next six years

(one for only nine months) until a commoner named Nabonidus (r.

ca. 556–539

B.C.E.) became king. He is reported to have angered

the Babylonian priestly hierarchy by demoting their supreme god,

Marduk, and replacing him with a non-Babylonian moon god, Sin.

Furthermore, Nabonidus sojourned for 10 years at the oasis of Teima

(in present-day Saudi Arabia), this forcing the cancellation of the

new year’s festival of Akitu, during which the king and the high

priest played important roles. Eventually, his reconsolidated state,

resting on the laurels of Old Babylonia, came to an end when another

king, Cyrus of Persia, moved into the capital without encountering

resistance.

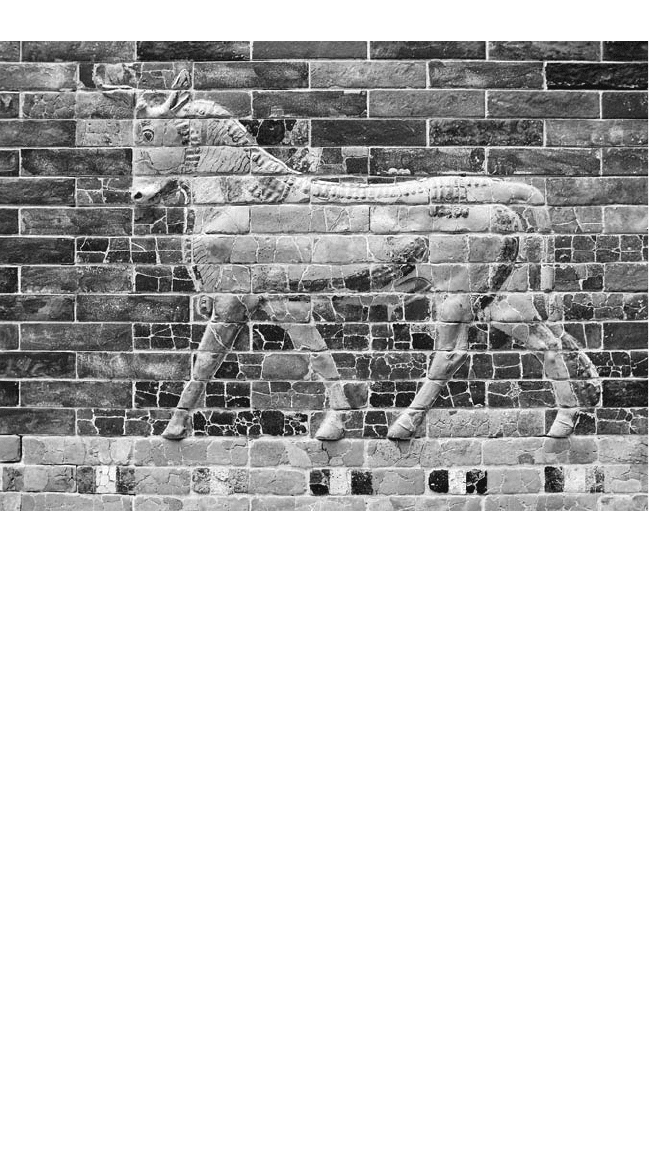

Detail of the reconstructed Ishtar Gate at the Pergamon Museum, in Berlin. The gate to

Babylon’s inner city was constructed ca. 575

B.C.E., during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II,

who conquered the kingdom of Judah and brought the Jews to Babylon in exile.

(Martina I.

Meyer/Shutterstock)

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

28

Conclusion

This chapter has traced the history of ancient Iraq over a course of

some 30 centuries, and what scintillating centuries they were. Even

though archaeologists, historians, and philologists are still far from

knowing the details of each and every century, let alone decade (and

there are huge stretches of time for which there are no records at all),

the overriding theme that emerges when studying those 30 centuries is

cultural unity despite constantly shifting borders. Permanent features

of this period are, fi rst, a lack of fi xed borders and the constant spread

of peoples and cultures throughout the region and, second, the assimi-

lation and integration of languages, cultures, and civilizations in an

unending search for new technologies and methodologies, commercial

exchange, and, not least of all, meanings in this life and the next. The

permeability of borders and the diffusion and absorption of languages

and cultures reinforced one another; as mutually supporting trends

of state and society, they gave impetus to the spread of novel ways of

understanding the world, worshipping the gods, the growing of new

crops, and the organization of fi scal, legal, and educational regimes.

Let us conclude with a description of the broad reception accorded

to Sargon’s rule in Sumer-Akkad. His impact was felt in regions far and

wide, not simply because of Sargon’s many conquests and achievements

but also perhaps because he was adopting modes of thought and orga-

nization long current in the region that made appeal to all cultures and

traditions. Oppenheim states:

Sargon remained a semi-mythical king throughout much of

the second millennium. The story of his birth and exposure,

his rescue from a basket floating down the Euphrates, his rise

to power, and last but not least, his campaigns, adventures,

victories, and reverses and his conquest of the West was read

in Amarna in Egypt, in Hattusa in Anatolia and even translated

into Hurrian and Hittite (Oppenheim 1977, 151).

29

2

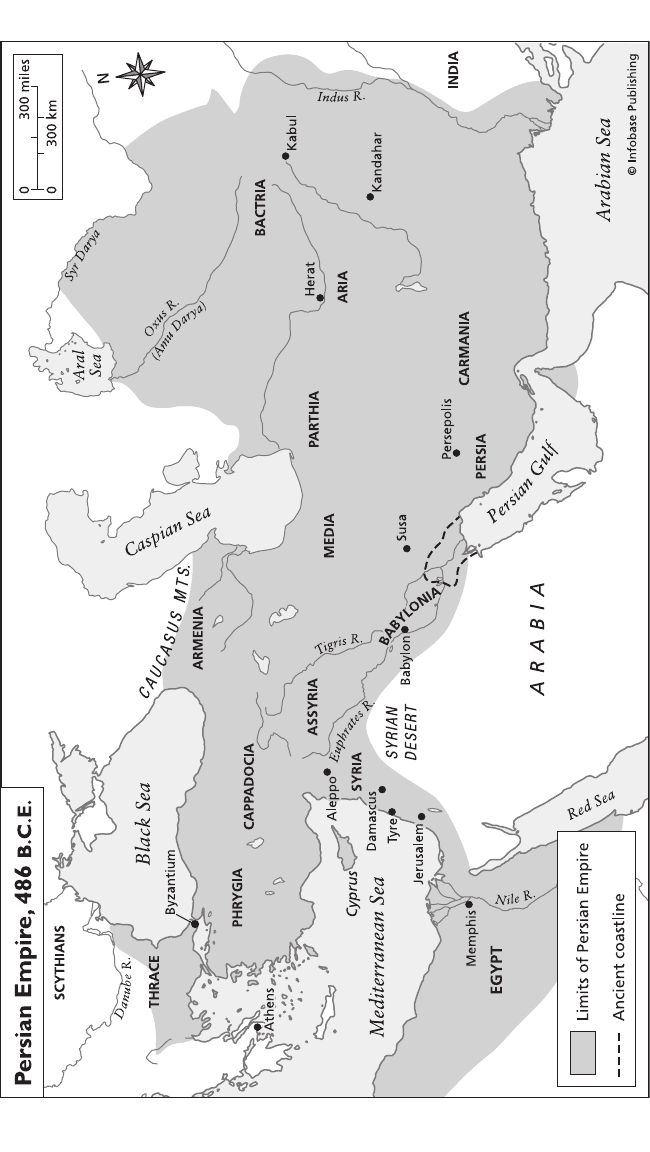

FROM THE PERSIAN EMPIRE

TO THE SASSANIANS

(539 B.C.E.–651 C.E.)

I

n the succeeding millennium, Mesopotamia, or ancient Iraq, con-

tinued to be a focus for invasion and conquest. Up to this period,

all overlords of Mesopotamia, with the probable exception of the

Sumerians, had been Semitic, but now, the conquerors came not from

nearby regions but from farther afi eld. They not only brought a fur-

ther intermingling of cultures in the alluvial plains of the Tigris and

Euphrates but relegated the area to a mere region of their far-fl ung

conquests. Under the Persian, Macedonian-Greek, Parthian, Roman,

and Sassanian Empires, the Assyro-Babylonian cities ceased to be great

capitals in their own right (although Babylon was still held in highest

regard even in the time of Alexander the Great); in fact, many were

destroyed in the conquests.

These empires left their marks on the land in many ways. With the

exception of the Romans, who only held portions of Mesopotamia,

each succeeding imperial dynasty contributed to the cultural history of

ancient Iraq, not simply its political and military histories. Art, archi-

tecture, religion, literature, law, and fi nancial institutions were all rede-

fi ned and expanded during this long period of struggle and takeover.

The Persian Empire (554–330 B.C.E.)

According to Greek sources, which, along with Neo-Babylonian docu-

ments, are frequently the only material available to trace the history of

the Persians, the latter hailed from southwest Iran and were led by a

man called Achaemenes, after which the Achaemenid dynasty takes its

name. Initially vassals of the Medes, the Persians, under Cyrus the Great

(r. 559–530

B.C.E.), defeated the Medes in about 550 B.C.E. and captured

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

30

their king, Astyages. Cyrus thereupon assumed the kingship of the Medes

as well, absorbing them and the territory they controlled into an empire

that would rapidly expand during the next 20 years. The Persians, at

least in the beginning, ruled in an almost indistinguishable style from

the Medes, so much so that the Greeks referred to them as Medes (Van

de Mieroop 2004, 268). There may also have been other reasons for that.

According to Greek historian Herodotus, Cyrus’s mother was actually a

daughter of Astyages, thus making Cyrus in part a member of the tribe.

Another ancient Greek historian, Ctesias of Cnidus, who stayed at the

Persian court around 400

B.C.E. and wrote several histories of the Persian

Empire, claimed that it was Cyrus who had married one of Astyages’s

daughters. If either or both of these accounts is legendary, they may have

been propagated to justify Persian rule over the Medes and their lands.

Further contributing to their legendary aspect is an account by the third-

century

B.C.E. Babylonian priest Berrossus, who placed Astyages at the

beginning of the Chaldean period (Sack 1991, 7).

During the course of the next 20 years, Cyrus overran Greek-speak-

ing Anatolia (the Asian part of Turkey), eastern Iran, parts of Central

Asia, and the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which controlled much of the

Fertile Crescent, an arc-like area stretching from the Persian Gulf

through Mesopotamia and into Upper Egypt. In 539

B.C.E., Cyrus

defeated the army of the last Babylonian king, Nabonidus (r. 556–539

B.C.E.), and made his son, Cambyses, king of Babylon. Historians have

speculated that Cyrus, aware of the power of the priestly hierarchy,

made Cambyses king to ensure the proper continuation of the Akitu

festival since Cyrus, himself, would be gone for long periods on the

battlefi eld. Like his Chaldean predecessors, Cyrus (as well as later

Achaemenid emperors) held Babylon in high esteem as the cultural

center of the ancient Near East. Not only did he preserve the city, but

in an echo of the rationalization used to justify his triumph over the

Medes, the royal inscription on what has become known as the Cyrus

Cylinder, a cylindrical clay tablet, has it that the Babylonian high god,

Marduk, chose Cyrus to reign over the empire. The Cyrus legend

extends further. Biblical accounts (among others) describe that the

year after Cyrus occupied Babylon, he allowed the Jews to return to

Judah after their nearly 50-year exile, begun during the reign of the

Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II. However, this is not confi rmed

by the Cyrus Cylinder. According to ancient historical texts, Cyrus led

military expeditions as far east as India.

In 530

B.C.E., Cambyses (r. ca. 530–522 B.C.E.) inherited the throne of

the Persian Empire and fi ve years later, conquered Egypt, becoming its

31

FROM THE PERSIAN EMPIRE TO THE SASSANIANS

M

A

C

E

D

O

N

I

A