Fattah H., Caso F. A Brief History Of Iraq

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

32

king. Cambyses remained in Egypt until 522 B.C.E., when he returned

to Babylon to oust a usurper of his throne (here the historical record is

unclear): either the magian (an expert in religious traditions) Gaumata

or his own brother Smerdis. Some accounts declare that Cambyses had

had Smerdis secretly murdered and that Gaumata assumed the throne

as the dead brother, while most claim that Smerdis briefl y held power.

Soon after his return to Babylonia, Cambyses died—whether of natural

causes, suicide, or at the hand of another is unclear—before removing

the usurper. That task was left to the man who became the next Persian

ruler, Darius I (r. 521–486

B.C.E.), also referred to as Darius the Great.

Darius was not a direct member of the royal line but claimed

Achaemenid kinship through his father, Hystaspes. The fi rst years of

Darius’s reign were marked by civil war throughout the empire. The

fi rst region to rebel was Babylonia, where a local leader “called Nidintu-

Bêl recruited an army by declaring that he was ‘Nebuchadnezzar,

son of Nabonidus’ and seized kingship in Babylon” (Roux 1980, 376).

Darius led an army against Nebuchadnezzar III (who ruled Babylon for

approximately two months) before destroying his army and executing

him in Babylon. The following year, yet another claimant to the throne

appeared, naming himself Nebuchadnezzar, but he met the same fate

as his predecessor. The unrest spread to other parts of the empire as

local tribes sought to take advantage of the disarray in Babylon. By 518

B.C.E., however, Darius had secured control over the empire. He then

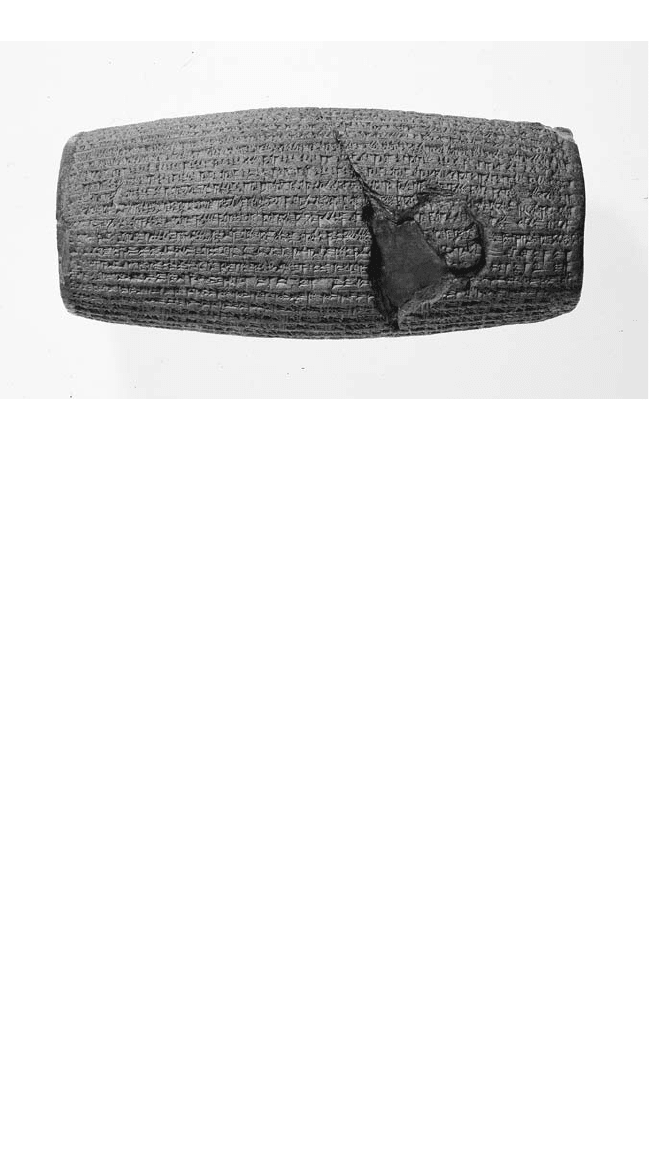

The Cyrus Cylinder, upon which is inscribed the Persian king’s conquest of Babylon at the

behest of Marduk, the Babylonian high god

(HIP/Art Resource, NY)

33

FROM THE PERSIAN EMPIRE TO THE SASSANIANS

set about expanding it, overwhelming parts of Africa, including Libya,

and annexing western India. Darius also set his sights westward where

the Hellenic city-states, just beyond the empire’s border, were the next

logical step. Part of Darius’s (and his successor Xerxes’) strategy in the

area was to pit the Greek city-states against one another, for “having

watched the Iraqi cities hack one another to pieces and so make their

conquest easy, Darius and Xerxes tried to apply the Iraqi lesson to

Greece. In one of the great turning points of history, they failed . . .”

(Polk 2005, 32). Darius was twice thwarted in his attempt at Greek

conquest: fi rst, when a Persian fl eet was destroyed in a storm in 492

B.C.E. and then, when his army was defeated by an Athenian army at

the Battle of Marathon in 490 B.C.E., which halted the Persian advance

in its tracks. Thereafter, the goal of conquering the whole of Greece

became one of the defi ning visions of the Persian rulers, attempted by

practically every one of them after Darius.

By the end of Darius’s reign, the Persian Empire stretched over

thousands of miles, from the Aegean Sea eastward to the Indus River,

and from Armenia in the north to Lower Egypt. Its rulers governed

a multitude of men and women and coexisted with several different

religions and cultures. The Persian Empire exerted infl uence on its con-

temporaries as well as its successors; for example, its lingering effects

were evident on the Sassanian Empire that followed in its wake, which

contributed to world civilization through its emphasis on the divine

rule of kings and the construction of imperial authority.

The Persian Empire under the Achaemenids was famous for its

building activities. In much the same vein as all the rulers and dynasts

that preceded them, the Persians built magnifi cent administrative capi-

tals, such as Persepolis (begun in 518 B.C.E.) and Susa, which consisted

of several palaces and large gardens. The most celebrated tradition asso-

ciated with some, if not all the rulers of the Persian Empire, however,

was the policy of toleration for all ethnic, religious, and social groups.

According to historian Marc Van de Mieroop, “it was the fi rst empire

that acknowledged the fact that its inhabitants had a variety of cultures,

spoke different languages, and were politically organized in various

ways” (Van de Mieroop 2004, 274). The Persians’ keen interest in pro-

moting effi cient government allowed them to retain the administrative

languages used by different peoples so as to be able to use them in local

affairs; as well, the inscriptions on the walls of temples or on monu-

ments were in several different languages, testimony to the diversity of

the empire, which at its height contained more than 70 ethnic groups.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

34

Imperial expansion aside, Darius left his mark on the empire through

its internal reorganization. Van de Mieroop theorizes that as a result of

the civil war and provincial uprisings, “Darius regularized control once

he was fully in charge. . . . [T]he empire was turned into a uniform

structure of about 20 provinces” (Van De Mieroop 2004, 272). The

provinces, or satrapies, were each ruled by a satrap, or governor. Over

time, those satraps became rival contenders for power because some of

them developed their own local power bases. Meanwhile, Babylonian

revolts and Egyptian insurrections strained the empire’s resources and

ate into its revenue. Equally signifi cant was the outsourcing of the

army, which went from a relatively professional organization to a body

composed almost entirely of mercenary troops, some of whose mem-

bers were Greek. Ultimately, the empire was too large to be controlled

exclusively by one dynasty, and in the end, it was a case of the middle

nibbling at the edges. By the end of the fourth century

B.C.E., this dete-

rioration made the Persian Empire ripe for conquest.

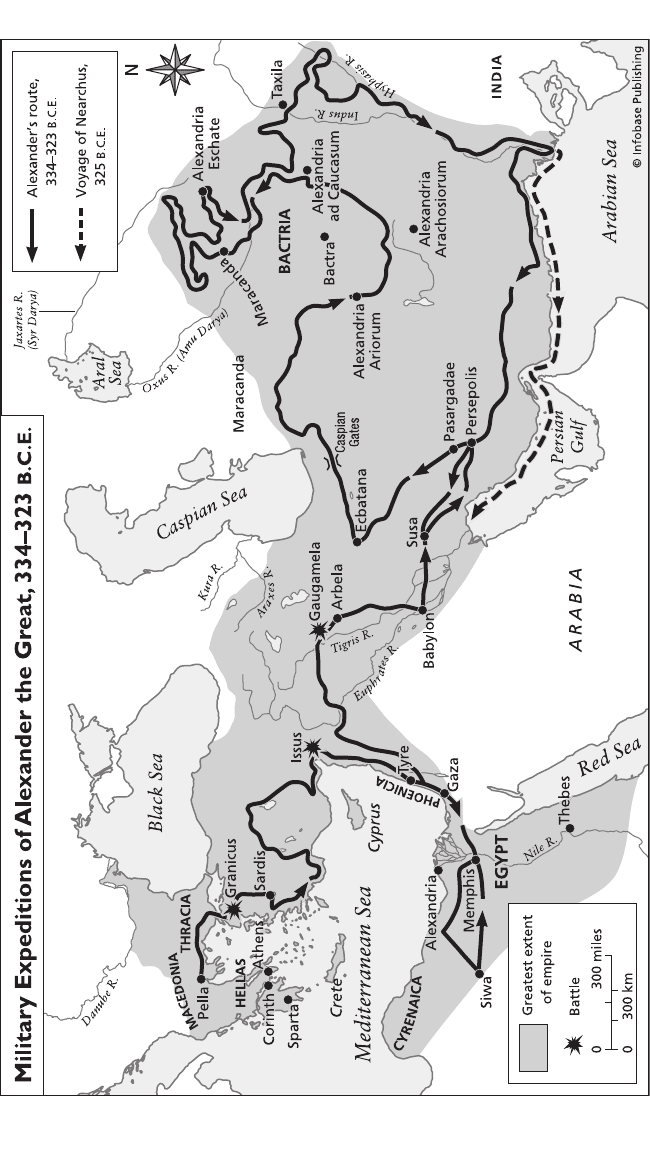

In the rough and rude environment of Macedonia (northern Greece), a

ruling family emerged that threatened the Persian Empire’s hold on power.

Taking a leaf from the Achaemenids’ book, Alexander of Macedon, who

became king in 336

B.C.E., started his long march toward the formation

Ruins of the ancient Persian capital of Persepolis, built in the late sixth–early fi fth century

B.C.E., located approximately 45 miles north of Shiraz, Iran (Steba/Shutterstock)

35

FROM THE PERSIAN EMPIRE TO THE SASSANIANS

of yet another sprawling empire, this time joining Persian administrative

experience to Hellenistic traditions. Reverting to local legacies of impe-

rial rule, he made Babylon his capital and restored the temple of Marduk,

Babylon’s reigning god. His practice of melding local institutions with

imperial rule, entirely in keeping with ancient precedent, marks him as

yet another proponent of the cultural unity of the region, of which ancient

Iraq, with its fl uctuating frontiers but its vastly absorptive civilization, was

perhaps a notable example.

Alexander the Great (r. 336–323 B.C.E.)

Alexander was born in Pella in 356 B.C.E., the son of the Macedonian

king Philip II, who had seized power just three years earlier. Alexander’s

mother, Olympias, was also of royal blood, being the daughter of the king

of Epirus. As a young man, Alexander was a student of Aristotle and by

the age of 16 was standing in for his father as leader of Macedonia when

Philip was off fi ghting against Byzantium. At age 18, Alexander was a

commander in his father’s army and played an important role in Philip’s

victory in the Battle of Chaeronea, in which the Macedonians defeated

an alliance of Greek city-states led by Athens and Thebes. Following

the victory, Philip founded the Corinthian League, named for the city

where representatives of the city-states met with the Macedonians to

unite Greece. The exception to the league was Sparta, which rejected

the terms imposed on the city-states by the victor. The true purpose of

the Corinthian League was to make war on the Persian Empire.

In 337

B.C.E., Philip divorced Olympias; during the feast celebrating

his father’s new marriage, Alexander and Philip quarreled so violently

that the former and his mother sought refuge in her family home-

land of Epirus. Alexander also traveled to Illyria during this sojourn.

The enmity between father and son ended soon enough, although

Alexander’s position was less secure than it had been. In 336

B.C.E.,

Philip sent an army of approximately 10,000 men, led by his general,

Parmenion, to capture the Greek cities in Anatolia under Persian con-

trol. At the time, the Persian Empire was undergoing its death throes.

Not only had the satrapies of Babylonia and Egypt revolted, but assassi-

nation had made the throne of Cyrus and Darius unstable. Before Philip

could join his army and lead it in conquest, he was assassinated by his

guard. Alexander, at age 20 and with the backing of the army, ascended

to the throne as Alexander III.

Alexander spent the next few years securing his hold on the king-

ship by forming alliances with important generals, including Antipater,

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

36

who became the second most powerful man in the kingdom, and

Parmenion, who still commanded the forces in Anatolia. He also made

war on recalcitrant Greek city-states. By 334

B.C.E., he was ready to turn

eastward and continue the war against Persia. No sooner had Alexander

begun his long quest for glory than the great king of Persia, Darius III

Codomannus, tried to make peace, but Alexander preferred to have

the Persian Empire. His fi rst battle pitted his army against a Persian

army made up largely of Greek mercenaries. Alexander’s victory at

the Granicus (Kocabas) River resulted in the slaughter of many of the

mercenaries, and those who managed to survive the defeat were sent to

Macedonia as prisoners and subsequently slaves. Over the course of the

next two years, Alexander battled in and conquered western and west-

central Anatolia (Phrygia). Then, in 333

B.C.E., he defeated the Persians

at the Battle of Issus, nearly capturing Darius III in the process. By fl ee-

ing the battlefi eld (and sacrifi cing his family to be captured), Darius

brought humiliation upon himself, as later ancient Greek historians

depicted his action as cowardice. However, his action preserved the

Persian Empire (at least for a few more years), which would not have

been the case had he been captured or killed. Darius even tried to ran-

som his family at one point, offering to Alexander all satrapies west of

the Euphrates River. In a famous anecdote, Parmenion is quoted as say-

ing, “I would accept [this offer] were I Alexander.” Alexander replied,

“I too if I were Parmenion.

Alexander then proceeded to pick off Persia’s Mediterranean satra-

pies: Syria, Phoenicia (modern Lebanon), and Egypt all fell to his army

over the next two years. In Egypt, he founded the city of Alexandria.

In 331

B.C.E., with the eastern Mediterranean seacoast fi rmly under

Macedonian control, Alexander headed for Mesopotamia.

The decisive battle of Gaugamela took place on October 1, 331

B.C.E. When it was over, it “opened for Alexander the road to Babylonia

and Persia” (Roux 1980, 381). Prior to the battle, Alexander had the

option of marching straight to Babylon, engaging a Persian army under

the Babylonian satrap Mazeus, or turning north to engage Darius in

Assyria. He chose the third option. Although the Macedonian army

was numerically inferior to the well-supplied Persian forces, they again

won the battle. How the battle was fought was unclear. Greek accounts

say that Darius fl ed the battlefi eld once again, while the Babylonian

account lays the blame on the Persian soldiers for having deserted the

king. At any rate, the Macedonians were free to take Babylon and the

entire satrapy of Babylonia, the wealthiest province in the empire. One

of the unintended consequences of Alexander’s marching into Babylon

37

FROM THE PERSIAN EMPIRE TO THE SASSANIANS

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

38

was the discovery of Babylonian astronomical tables that were more

accurate than those the Greeks used, forcing the latter to revise their

calendar.

According to the classical Greek historians, Alexander was hailed as a

liberator by the Babylonians, who only a few years earlier, had had their

own revolt put down by the Persians. Yet, as Van de Mieroop points

out, these accounts are “to a great extent Macedonian propaganda . . .

and most people probably saw little difference between the old and

new regimes” (Van De Mieroop 2004, 279). Possibly one of the reasons

for this was because Alexander retained Mazeus as satrap of Babylonia.

Nevertheless, Alexander followed Cyrus’s lead in gaining favor with

Babylon’s aristocracy, especially the religious elites, so as to make his

kingship more acceptable to the people. He especially paid homage to

the Babylonian supreme god, Marduk, by undertaking the rebuilding

of the temple dedicated to that god. Alexander remained in Babylon for

approximately one month, before turning toward Persia itself.

Alexander’s campaign into Persia marked (at least superfi cially)

a departure from what had preceded it. Whereas the dismantling of

the Persian Empire in Anatolia, Egypt, and Babylonia had been under

the guise of liberation, the same could not be said of Persia. Though

they were no longer fi ghting against mercenaries or overlords but

against people whose sole aim now was to protect their homeland,

the Macedonian army was invincible. One by one the great cities fell:

Persepolis, Susa, and Pasargadae (Cyrus’s capital, founded near the

site of his victorious battle against the Medes and where all subse-

quent Persian kings were invested). Persepolis, in particular, was laid

to waste, presumably in retribution for the Persian attack on Athens.

Despite these successes, Alexander had not managed to capture Darius,

who was king of the Persians in name only.

His base of power nonexistent, Darius fl ed eastward, where he was

eventually held captive by the satrap of Bactria, Bessus; however, before

Bessus could bargain with Alexander, the Macedonians attacked, in July

330

B.C.E. Darius was killed during the ensuing battle, most likely by

his captors. This worked to Alexander’s advantage as he was able not

only to give Darius a state funeral but to legitimately—from his per-

spective—claim the crown. For the next six years, Alexander continued

his eastward campaign, reaching as far as the Indus River. His conquests

were brought to a halt not by a superior army but by his own soldiers,

who in 324

B.C.E., refused to continue making war. Far away from their

homeland and exhausted by more than 10 years of conquest and put-

ting down revolts among already conquered peoples, the Macedonians

39

FROM THE PERSIAN EMPIRE TO THE SASSANIANS

revolted against Alexander, essentially forcing him to turn back. He

reached Susa later that year and married two Achaemenid princesses so

as to cement his claim to the throne. Meanwhile, the Macedonians were

becoming alarmed as Alexander increasingly assumed the trappings of

the Persians.

Early in 323

B.C.E., Alexander returned to Babylon, which he decided

to make his capital. Following a night of heavy drinking, Alexander fell

ill; he died a few days later, on June 11, 323

B.C.E. Although it has never

been proven, historians lean to the theory that Alexander was mur-

dered, most likely by disenchanted comrades, although he had made

enemies among the so-called religious elite of Babylon, too. Whatever

the truth, Alexander’s death spared Arabia from Macedonian conquest;

Alexander had been eager to begin a campaign in that region.

Alexander’s empire was the fi rst spread of Hellenistic culture outside

of western Anatolia and the Mediterranean area. However, the farther

from Macedonia it expanded, the weaker it became—and this was seen

after Alexander’s death—which was probably Alexander’s main reason

for deciding to make Babylon his capital. One of the world’s great cul-

tural cities, Babylon would remain important for nearly another millen-

nium. The claim that the Macedonian conquests helped invigorate the

ancient Near East has come under revision in the past 20 years. Some

historians have gone so far to regard this notion as “an example of, and

justifi cation for, nineteenth-century European colonial enterprise in

regions that had known a glorious past but had not modernized” (Van

De Mieroop 2004, 280). Still, Alexander did not pursue only warfare

and conquest; he was a founder of cities.

Alexander’s death left the empire without a clear successor, and the

Macedonian generals immediately conferred in hopes of coming up with

an amicable solution. They were unsuccessful. The result was not only

civil war but revolt in the eastern satrapies. From the time of Alexander’s

death until the end of the fourth century

B.C.E., the Diadochi, or “suc-

cessors,” engaged in four wars: in 322, 318, 314, and 307

B.C.E. By 320

B.C.E., the various Macedonian factions had briefl y exhausted themselves

and met at Triparadisus (in Syria) to hash out an agreement as to how the

empire should be divided, with each of the various generals reigning as

satraps. While many areas were parceled out to various generals, essen-

tially Antipater became regent for Alexander’s young son, Alexander IV,

and would control Macedonia and Greece. Meanwhile, Ptolemy was to

get Egypt, where he established a dynasty that lasted until the late fi rst

century

B.C.E., when the last of the Ptolemaic rulers, Cleopatra, commit-

ted suicide and Egypt became a Roman province. Antigonus controlled

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

40

Syria. And the fi nal prize, Babylon, went to Seleucus, who would himself

establish a dynasty and empire.

Seleucid Empire (312–64 B.C.E.)

The division of Alexander’s erstwhile empire was harder on Babylonia

(and Syria) than the conquest had been. Historian Amélie Kuhrt has

observed that “the worst consequence for Babylonia of the Macedonian

conquest was undoubtedly the long-drawn-out and disastrous wars

between the Diadochi in which Babylonia . . . was frequently the cen-

tral arena” (Kuhrt in Kuhrt and Sherwin-White 1987, 51). The war-

fare that followed was strictly between the Macedonian satraps; the

Babylonians themselves accepted a Macedonian overlord. As historian

Susan Sherwin-White notes, Babylonian Chronicle Number 10 “does

not question the validity of, or regard as illegal Seleucus’s position as

satrap, which is simply accepted by the author” (Sherwin-White in

Kuhrt and Sherwin-White 1987, 15). By 316

B.C.E., Seleucus was at

war with Antigonus, the satrap of Phrygia. Antigonus briefl y gained

the upper hand, forcing Seleucus to fl ee to Egypt, where Ptolemy was

fi rmly lodged. (Ptolemy, in fact, chose Egypt as his share of the divi-

sion because of its remoteness, thus, in the years just after Alexander’s

death at least, making it less susceptible to the constant warfare that

plagued the other satrapies of the empire.) In 312

B.C.E., Seleucus

regained Babylonia and once again ruled from Babylon. The Seleucid

dynasty is measured from this date. In time, the empire that Seleucus (r.

312–281

B.C.E.) and his successors forged became the largest of the suc-

cessor states to Alexander’s empire. During the next decade, Seleucus

managed to place himself on equal footing with Ptolemy by expand-

ing his empire. A détente with Antigonus, who, himself was looking

westward to Athens, combined with earlier victories over Demetrios

and other satraps under Antigonus, allowed Seleucus to turn his army

east, whereupon he conquered what had been the Iranian satrapies.

By 305

B.C.E., he, like the other Macedonian satraps, declared himself

king and ruled not from Babylon but from Seleucia, a city he founded

on the Tigris River south of Babylon. Seleucia was not a capital in the

classical sense; as historian John D. Grainger points out, “the kings

were peripatetic in the fi rst century or so of the [Seleucid] kingdom’s

life” (Grainger 1990, 122). Seleucus had forsaken Babylon (he would

later forsake Seleucia) as an administrative center, and this required

that many Babylonians relocate to the new city. Despite the fact that

Chaldean astrologers remained, the legendary city began its slow

41

FROM THE PERSIAN EMPIRE TO THE SASSANIANS

decline. Still, in Seleucid times, Babylon was a somewhat autonomous

city locally ruled by, to quote historian R. J. van der Spek, “the atammu

(the chief administrator of the temple [Esagila]) and the board called

‘the Babylonians, (of) the council of Esaghila’ ” (van der Spek in Kuhrt

and Sherwin-White 1987, 61).

As had Cyrus and Alexander before him, the “peripatetic” Seleucus

campaigned in India, but to less success. First, he came up against

the Mauryan Empire, whose king, Chandragupta, had taken over

Alexander’s Indian possessions. Then, Seleucus was forced to return to

Mesopotamia to join the alliance against Antigonus and Demetrios in

the Fourth Diadochi War. Seleucus’s entering the fray tipped the scales

against Antigonus. Seleucus defeated and killed him in the Battle of

Ipsus in 301

B.C.E. and took Syria as his prize. By then, his title was

Seleucus I Nikator (Conqueror). Seleucus eventually moved his capital

from Seleucia to Antioch on the Orontes River in Syria, and it was clear

that Seleucus hoped to reunite Alexander’s empire with himself as king.

Intrigues and interdynastic marriages, as well as city foundings and the

organizing and administrating of his empire, occupied him for most

of the rest of his life, but in 281

B.C.E., he invaded the territory of his

former ally, Lysistratus, northwest of Syria. Having defeated Lysistratus,

who died in the battle, Seleucus entered Europe, with plans to march

to Macedonia, but he was assassinated (in 281

B.C.E.) before achieving

his goal.

In many ways, it appears that the Babylonians were content to

remain a satrapy under the Seleucids, even as to forsaking the capital

of the empire to Syria. The Seleucids, even in the later stages of the

empire, ruled Babylonia in the spirit of Alexander. While Babylon’s

decline can be traced to the transfer of the imperial capital and the

widespread diffusion of Hellenic culture throughout the territories

of the former Persian Empire, some historians contend that Babylon,

itself, did not decline under the Seleucids. However, one of the later

kings, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, hoped to populate the city with

Europeans. That aside, Sherwin-White has noted that the formal

administrative functions of the satrapy were conducted not just in

Greek but also in Aramaic and Akkadian (Sherwin-White in Kuhrt

and Sherwin-White 1987, 23–24). This is corroborated through

various documents of the period, including taxation documents as

required by the reorganization of the imperial taxation system under

Antiochus I, Seleucus’s successor. In this and other cultural aspects

(such as temple building), as Sherwin-White contends, the Seleucid

kings acclimated their rule to Babylonia.