Fouracre P. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 1: c. 500-c. 700

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Celtic kingdoms 233

Though these areas were all therefore indubitably Celtic, we should no more

expect political or cultural homogeneity than we would of Germanic-speaking

parts at this time. They did not form a single political unit; there was not

even one kingdom per Celtic ‘country’, but several or many; and some regions

did not form a part of any kingdom. In fact, their political structures were

in some respects influenced by their experience of the Roman past. Brittany,

south-western England and Wales had all been part of the Roman Empire,

though the level of participation in Roman material culture and civic life varied

enormously across them and though some parts had frequently had a military

presence; eastern Brittany and south-east Wales had been more affected, and

the coasts of Wales, at least, had had forts built and refurbished in the late fourth

century. Lowland Scotland, or more precisely the land between Hadrian’s Wall

and the Antonine Wall, had also at times in the second century been a part

of the Roman Empire, and subsequent to that appears to have had a close

relationship with imperial governors. Scotland north of the Antonine Wall

lay outside the Empire, although Agricola had campaigned in the east in the

distant past, and Ireland and the Isle of Man always lay outside it. With such

major differences in background, it would be surprising if post-Roman polities

had all taken the same shape.

4

There are also, of course, fundamental differences in geography between

Celtic areas, such that one would expect neither economy nor politics and

society to be the same all over. Much of Wales is high plateau and much of

Scotland is high mountain. Not many people can have lived in these areas and

settlement must have concentrated in the coastal lowlands – in the Scottish

case in the Western Isles in particular – and in the limited zones of good work-

able lowland in south-east Wales and eastern Scotland. Ireland and Brittany

are quite different; though both have their mountainous parts, they have much

less upland than Wales and Scotland, and there is no reason to suppose that the

population was anything other than broadly distributed across these regions;

both also have substantial areas of high-quality arable land. Cornwall is very

similar geographically to western Brittany, while the Isle of Man has a micro-

cosm of Irish landscapes. There are differences, then, both within regions and

between them. Accordingly, communication across Wales and Scotland was

exceptionally difficult, and communication across Brittany was as difficult as

land transport was anywhere in western Europe (although it is likely that

the east/west Roman routes were still in operation in the seventh century).

In all three, movement by water was far more practicable than over land,

and coastal areas therefore have an especial significance. Ireland was a land

crossed by major waterways, and dotted with many lakes, and this must have

4

Cf. Halsall, chapter 2 above.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

234 w endy davies

made communications vastly easier here than was the situation in other Celtic

areas.

The very early Middle Ages was a period of climatic deterioration. With a

drop in temperature and increase in rainfall since the late Roman period, the

highlands would have been even less suitable for cultivation than previously,

and marginal lands here and there would have dropped out of use completely –

as demonstrated very precisely by excavations at the Roman farm of Cefn

Graeanog in north-west Wales, once a cereal-growing area but no more so in

the early Middle Ages than it is now.

5

This made the good agricultural lowland

even more significant. The other major change in economic determinants

in this period was demographic: the sixth and seventh centuries were times

of recurrent plague. We know that the plague of the 540s had effects across

Wales and Ireland, while that of the 660sis believed to have had major social

consequences in Ireland; it certainly reduced recorded activity for a generation.

6

When we remember the fundamental consequences of the plagues of the late

Middle Ages, we should be prepared for comparably significant effects at this

earlier period.

Despite the geographical differences, the economic base in Celtic areas was

one of mixed farming, supplemented by hunting and gathering when appro-

priate. The balance of the several elements in a mixed farming economy would

of course have varied from place to place, and there is reason to suppose that

Irish farming put greater emphasis on cattle rearing, while farming in eastern

Brittany put more on cereals (and also fostered some specialisation in the culti-

vation of vines). These were all economies that were characterised by relatively

little commercial exchange, and many economic units may well have been

for the most part self-sufficient. However, this does not mean that the areas

lacked wealth or wealthy people: surplus was generated, and was monopolised

by aristocrats here as elsewhere. Some groups or families or some individuals

had the capacity, therefore, to patronise the importation of pottery from the

continent through the sixth and much of the seventh century.

7

There was

certainly some exchange, and this movement of pottery is the most visible

expression of it, but everything suggests that its volume, and proportion of

total production, was tiny. Not surprisingly, then, these are areas of little or

no urbanisation; overwhelmingly rural, in most parts there were no towns at

all; Roman Caerwent almost certainly supported a monastery by the late sixth

century but no urban life; Roman Exeter and Roman Carlisle probably had

much reduced quasi-urban communities; Roman Carmarthen may have had

5

Goodburn, Hassall and Tomlin (1978), p. 406;Weir (1993).

6

Annales Cambriae s.a. 547, 682, 683; Annals of Ulster s.a. 545, 549, 664, 665, 668;Baillie (1995).

7

Campbell (1984), and comments following his paper; Thomas (1990), Campbell and Lane (1993),

Wooding (1996), Hill (1997).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Celtic kingdoms 235

nothing left but dilapidated buildings. It was only in eastern Brittany that

towns continued to have some sort of urban character, and Rennes, Nantes

and Vannes remained urban centres throughout this period. Ireland com-

pletely lacked towns, but it did not lack development. Alone among Celtic

areas, there are signs in the seventh century of increasing and increasingly

specialised production, particularly in the context of patronage from well-

established monastic communities, and this is sufficient to suggest that by

700 Ireland was in the midst of an economically developing trend. The same

could be true of eastern Brittany at that time, but we lack the sources to

demonstrate it. It does not seem to have been the case in Cornwall, Wales or

Scotland.

The structure of Celtic societies in the sixth and seventh centuries is also

complicated by the migration factor and its uneven operation, as are societies in

so many other parts of western Europe. Some British (and one or two English)

went to Ireland, especially in the context of Christian missions, but on the whole

Ireland was unaffected by immigration. People had left Ireland, however, both

to raid and to settle in western Britain in the fourth and fifth centuries, and

that movement continued into the late sixth century. The settlement of Ulster

ruling families in south-western Scotland and the Isle of Man in the 560s–580s

is of the greatest importance for the future development of those areas, and it

is also quite likely that some southern Irish were ruling in parts of west Wales

in the early sixth century.

8

Whether or not these leaders were accompanied

by sufficient settlers to constitute a mass migration is a contentious issue; the

Irish-speaking populations of south-west Scotland and Man may have settled

there in the late sixth century, or in the preceding two centuries, or even much

earlier; there is, however, absolutely no doubt about the movement of leaders

at that time, nor of the fact that the populations of those areas were or became

Irish speakers.

There is also good reason to think that there had been some significant

movement of British people in the fifth century, and it is likely that some

of this continued in the decades after 500.No one believes nowadays that

all the British (the indigenous population of Britain) were pushed westwards

by the Angle and Saxon settlers, for it is perfectly clear from seventh-century

and even some later texts that a Brittonic language was still being spoken in

parts of midland and eastern England long after the English settlement. Some

British kingdoms also survived in central and northern England until well into

the seventh century. However, the early borrowing of Latin words into Welsh

8

Annals of Ulster s.a. 574, 577, 580, 582. Later texts record a very strong tradition that some of the Irish

D

´

eisi migrated to Wales round about the fourth century. Several generations from the Irish genealogy

also feature in the genealogy of the south-western Welsh kingdom of Dyfed, at a phase which could

correspond with the late fifth/early sixth century; Bartrum (1966), p. 4; Thomas (1994), pp. 53–66.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

236 w endy davies

makes it likely that some part of the British people – perhaps the wealthy and

aristocratic, perhaps the higher clergy – did indeed move westwards, though

we cannot begin to guess at the proportion of the total population.

9

It is

also quite clear that some of them went overseas to northern France: by the

mid-fifth century there were British on the central Loire and in north-western

France; and by the late sixth century there were sufficient numbers settled in the

north-west for the peninsula to change its name from Armorica to Britannia

Minor – ‘Little Britain’ or, as we know it, Brittany.

10

We cannot plot this

migration precisely, but it seems to have been over by the 560s. Nor dowe

know much about the circumstances of it, although there is a Welsh tradition

that it was plague that sent peoples overseas:

11

we do not know if the several

groups of Britons scattered about fifth-century France eventually filtered back

into the north-west, or if more and more kept coming from Britain. We also

do not know if the British settlement of Armorica was vastly more dense in the

west, although seventh-century differentiation between the land of the Britons

and that of the Romans may imply that.

12

It is, however, perfectly clear that

there were Brittonic speakers in eastern Brittany, for ninth-century personal

and topographic nomenclature is overwhelmingly Breton; and although sixth-

century Frankish writers saw the River Vilaine as the boundary between Bretons

and Franks, Breton-speaking even occurred to the east of that line. It may

indeed be that the River Vilaine constituted the boundary between Britannia

and Romania; if so, that boundary lies well into the east of the peninsula.

How many of the Britons/Bretons of the sixth century and the ancestors of the

Breton-speakers of the ninth actually came from Britain and how many were

the descendants of the continental Celts of the Roman period is impossible to

say. It is a hotly debated issue among Breton scholars and the arguments easily

become circular.

13

The problems surrounding migration issues, whether they relate to Brittany,

to England or to Scotland, are severe and most appear incapable of solution.

The movements cannot be dated with any precision. We have very little idea

of numbers of people involved, either relative or absolute; we have little idea

of social composition (did whole communities move, or bands of independent

fortune hunters, or aristocrats and would-be rulers, or different combina-

tions in different places?); and we do not know enough about the relation-

ship between linguistic change and settlement. There is no doubt that mass

migration can change the language of a region, but we have little idea of the

9

Jackson (1953), pp. 77–86;Dark(1993), p. 91.

10

Concilia Galliae A.314–A.506,p. 148; A.511–A.695,p. 179;Gregory, Hist. iv.4.137, v.26.232, x.9.493.

11

Book of Llan D

ˆ

av,pp. 107–9.

12

Concilia Galliae A.511–A.695,p. 179; Vita Samsonis i.61.

13

Cf. Falc’hun (1970), pp. 43–96;Galliou and Jones (1991), pp. 143–7;Tonnerre (1994), pp. 33–74;

Astill and Davies (1997), p. 113 n. 12.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Celtic kingdoms 237

minimum proportions necessary to effect such a change.

14

Place-name evi-

dence can be extremely helpful in suggesting the location of speakers of this or

that language/dialect, but even here we have to be careful in our assumptions

about who did the coining of names: was it the residents of a place, or their

neighbours, or some alien who was making records for fiscal, proprietary or

navigational purposes? It is frustrating that we cannot solve these problems, but

we should not forget them: migration itself was obviously of enormous political

importance at the time and of enormous social consequence subsequently.

sour ce material

The written sources available for considering Celtic areas in the sixth century are

exceptionally few and are in some parts little better for the seventh, although by

then Irish material is rich and varied. What sources there are can be fragmentary,

corrupt and difficult to interpret. We therefore cannot ignore the fact that

there are very severe source problems in dealing with Celtic areas in the very

early Middle Ages; this means that it is impossible to make a well-evidenced

assessment of political history anywhere in the first half of the sixth century, and

this remains the case in some parts for most of the seventh. From the middle

of the sixth century northern Ireland and western Scotland are reasonably well

covered, as increasingly are other parts of Ireland in the seventh century; we

can discover this and that about Wales and eastern Scotland, but there is little

to flesh out the bare notices of a king here, a death there; what we know of

Cornwall and the Isle of Man is fragmentary in the extreme; we get a detailed

glimpse of east Breton affairs in the late sixth century but can see virtually

nothing for the succeeding century and a half.

In this situation, the evidence from stone inscriptions has a particular impor-

tance, for many survive in the original (virtually the only texts to do so) and

can be surprisingly detailed, yielding material descriptive of status, character

and events as well as names and funerary evocations. Not all inscriptions are

precisely dated, but some are, and many can be reasonably dated to within a

half-century or so. The Welsh corpus of inscriptions is well studied and espe-

cially important, but there are plenty of inscribed stones from Cornwall and

Scotland, some from Brittany, and a few of this period from Ireland and the

Isle of Man. Most are inscribed in the Latin language, but some use the Irish

alphabet ogham, either alone or in association with Latin.

15

14

See Koch (1997), pp. xlii–xliv, for some thoughtful comments on the process of linguistic change in

the early Middle Ages.

15

Macalister (1945–49); Nash-Williams (1950); Bernier (1982); Okasha (1993); Thomas (1994), for easy

reference, although there are subsequent discoveries published in many separate journals; see also

McManus (1991).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

238 w endy davies

Annals, contemporary notices organised by year, were clearly being main-

tained in some Celtic religious centres from the late sixth century, although

these records are usually brief, sometimes cryptic and often intermittent. At this

period they characteristically comprise obits of kings and clerics, and notice of

battles, disasters and climatic or astronomical phenomena. The northern Irish

series, which lies at the base of the Annals of Ulster and is often referred to as

the ‘Chronicle of Ireland’, is important for its coverage of northern Ireland,

western Scotland and the Isle of Man, though some of its material also found

its way into the Welsh collection, Annales Cambriae.

16

It is extremely likely

that the monastery of Iona was the initial source of these records, running

from shortly after its foundation in 563 until c.740,but by the late seventh

century records from Irish centres like Armagh and Clonfert survive, some of

which came to be incorporated into the Annals of Ulster and some in other

major collections such as the Annals of Inisfallen.A very small number of Welsh

annals survives from these centuries, some of Welsh and some of north British

origin; and we should not forget that the annals of the English Anglo-Saxon

Chronicle sometimes refer to Scotland, Wales and the South-West.

A small number of contemporary saints’ lives survive from this period and

these have a significance for more than purely religious affairs. They are the

u and T

´

ırech

´

Lives of Patrick by Muirch

´

an, and the Life of Brigit by Cogitosus,

while parts of another Life of Brigit are reconstructable from the so-called Vita

Prima – all come from Ireland and all from the second half of the seventh

century; from Iona we have Adomn

´

an’s Life of Columba, written c.700, and

from Brittany the anonymous Life of Samson, probably written round about

the mid-seventh century (though Breton, it is largely about Samson’s early

life in Wales).

17

A considerable body of ecclesiastical material survives from

seventh-century Ireland – penitentials, canons, tracts – but they will not be

considered here; and there are also records of sixth-century ecclesiastical coun-

cils involving Brittany. There are scholarly works of various kinds, especially

from Ireland, dealing with computation, language and grammar, and there are

works designed to show off literary skills, like the Hisperica Famina and Latin

poems and hymns.

18

There are also miscellaneous narratives – tracts and his-

tories – of value to the historian: for western Britain, the tract on the present

‘ruin’ of Britain by Gildas, written c.540 or a little earlier; for Britain and

Scotland especially, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, written a

16

SeeHughes (1972), pp. 99–159, and Grabowski and Dumville (1984), for critical assessment.

17

Lives of Patrick: Bieler (1979), pp. 61–166; Lives of Brigit: Acta Sanctorum Feb. 1 (1658), pp. 129–41 and

Vita Brigitae, ed. Colgan (1647), pp. 527–45 (see McCone 1982); Life of Columba: Vita Columbae;

Life of Samson: Vita Samsonis (see Wood (1988)).

18

Hughes (1972), pp. 193–216; OCr

´

´

oin

´

ın (1995), pp. 197–221;Davies (1982a), pp. 209–14;Herren

(1974–87).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Celtic kingdoms 239

couple of centuries later; for Brittany, the Te n Books of History by Gregory of

Tours (often called The History of the Franks), written in the late sixth century,

and also the Chronicle of Fredegar written in the mid-seventh.

19

The mixture

of material put together in north Wales in the early ninth century under the

title Historia Brittonum contains little that is useful for this period, although

it includes some brief notes of north British origin, which are exceptionally

important.

20

There are also some Irish tracts of legal and political concern, like

the Latin tract on the ‘Twelve Abuses’ and the vernacular Audacht Morainn

ain Adamn

´

and C

´

ain.

21

Most of the enormous corpus of vernacular Irish legal

material belongs, however, to the eighth century.

22

There are, finally, large genealogical collections from Ireland and Wales, the

latter including genealogies from southern Scotland and the Isle of Man; and a

few from Devon and Cornwall, and Brittany. These are potentially relevant to

political structures in the seventh century, and even the sixth, but are difficult

to use because, like the kinglists of the Picts or the Tara kings, they were

mostly drawn up several centuries after this period. They purport to record very

long pedigrees of dynasties ruling at the time of each genealogy’s compilation;

for example, the collection in BL Harleian MS 3859 from mid-tenth-century

Wales begins with pedigrees of two principal ruling families of tenth-century

Wales, extending back over more than thirty generations; the sections which

approximate to the seventh to tenth centuries are at least credible, but some

earlier sections are definitely not. In the absence of corroborative evidence it

is very difficult to assess the value of the putative sixth- and seventh-century

stages of this material; they could as well be wishful thinking, or mistakes,

as records. That said, there are genealogies that – terminating well before the

tenth century – must derive from much earlier records, like that for the Isle of

Manin the Harley collection; they are therefore potentially relevant source

material. The English genealogical material and regnal lists incorporated in

the Historia Brittonum are of comparable value to this latter group.

23

19

Gildas, De Excidio;onBede, Thacker, chapter 17 below; on the work of Gregory of Tours, Van Dam,

chapter 8 above; and on the Chronicle of Fredegar,Fouracre, chapter 14 below.

20

Historia Brittonum (often known – inaccurately – as ‘Nennius’); cf. Dumville (1972–74, 1975–76,

1985); Jackson (1963); Koch (1997).

21

Audacht Morainn.Meyer (1965); only a part of this text is of seventh-century date: see N

´

ıDhonn-

chadha (1982).

22

Welsh vernacular poems, Canu Aneirin and Canu Taliesin especially, may have a seventh-century

origin, but the redactions we have can be no earlier than the ninth century, and could be from as

late as the eleventh century; for a summary of the problems, see Davies (1982a), pp. 209–11; see

also Koch (1997). Some Irish vernacular tales could have been written down in the seventh century

(Carney (1955), pp. 66–76) but it would be conventional to date these to the eighth or ninth.

´

23

O’Brien (1962); Bartrum (1966); O Riain (1985); Breton genealogies are not collected but most are

cited in La Borderie (1896–98). Pictish kinglists: Anderson (1973); Tara – see Byrne (1973), pp. 48–69,

and see below, p. 243.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

240 w endy davies

the irish

There are two especial problems conditioning our understanding of the earliest

Irish history and both derive from the character of the available written sources.

The first concerns the annals: the Annals of Ulster, like many of the principal

collections, have a series of entries running through the fifth and sixth centuries,

and at first glance appear to provide us with very detailed evidence of people,

places and events in that early period. This is exceptionally misleading, for

most of this material was compiled and inserted by the historians of the late

ninth and tenth centuries who created the main collections: they did their best

to include the heroes of the past, both ecclesiastical and secular, in a credible

chronological framework.

24

What they produced is indeed credible, but its

place in the sequence is deduced and its historicity is unverifiable; it does not

therefore have the same status as evidence as the material that begins in the

late sixth century. The second problem is a related one: such was, and is, the

power of legend that it tends to determine the framework of all discussion of

these early centuries, whether that discussion took place in the ninth century,

or the twelfth, or the twentieth. One story is especially powerful, the story

that dominates the Ulster Cycle of tales, whose most famous elements come

together in the T

´

oCualnge (the ‘Cattle Raid of Cooley’).

25

This is set in a

ain B

´

world in which the Ulster people, the Ulaid, politically dominated the whole

of northern Ireland, with no hint of the existence of the U

´

ıN

´

eill family (who

in fact did dominate northern Ireland for much of the early Middle Ages).

The context is seductive and very easily leads us to assume that the Ulaid did

indeed ‘rule’ the north in the late prehistoric period.

Another problem that confronts the ordinary reader is the complexity and

unfamiliarity of the political structures that characterised sixth- and seventh-

century Ireland. Ireland had many political units at this time, of exceptionally

small size – maybe fifty, maybe a hundred, maybe even more of them – and

known as tuatha. Each tuath had its r

´

ı, its king, who had military and gen-

eral responsibilities for the polity but who was not – except in special circum-

stances – a legislator

26

.On top of this base, the political system admitted over-

lapping structures of overkingship: some kings were also overkings. This meant

that they expected military support from their underkings, and tribute too,

but it gave them no rights of interference in the tuatha of their underkings nor,

in practice, any habit of interfering, as far as we can see. Overkingship was not

merely a two-way relationship: some overkings were overkings of overkings

and correspondingly some were at once overking of one group of kings but

underking of another more powerful overking; and so on. To add to the

24

Hughes (1972), esp. pp. 142–6;Smyth (1972); Grabowski and Dumville (1984), p. 93.

25

T

´

ain; and see comment above, n. 22.

26

SeeWormald, chapter 21 below.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

241 The Celtic kingdoms

complications, at this time overkingship was not institutionalised: overking-

ships were established here and disappeared there in accordance with the polit-

ical realities of the moment.

We know vastly more about northern Ireland in this period than about

other parts. Its politics, in so far as we can perceive them, were dominated

bya complex interplay between the different branches of the U

´

ıN

´

eill family

and the rulers of the Ulster people, the Ulaid. By the late sixth century, four

major Ulaid tuatha occupied the extreme north-east of Ireland (Co. Antrim

and Co. Down) and were ruled respectively by the dynasties of D

´

al Riata,

al nAraide, D

´

D

´

al Fiatach and U

´

ıEchach Cobo. Usually one of them was

also Ulaid overking. The U

´

ıN

´

eill family, that is those families who believed

themselves to be descendants of the legendary Niall (pronounced Neil) of the

Nine Hostages, had branches based across northern and central Ireland. Of

these branches Cen

´

ogain, Cen

´

el Cairpri (Co. Donegal)

el nE

´

el Conaill and Cen

´

were most prominent in the north, while Cen

´

el nArdgaile

el Loiguire and Cen

´

(Co. Meath) were prominent in the midlands; they are known as northern and

southern U

´

ıN

´

eill respectively. Their pattern of behaviour suggests that the U

´

ı

N

´

eill kings not only sought to make themselves overkings with respect to their

own localities but also sought to make themselves overkings with respect to each

other. This process only reached its logical conclusion after our period, with

the establishment from the 730sofa single U

´

ıN

´

eill overkingship alternating

between northern and southern branches. Ulaid and U

´

ıN

´

eill were not the

only people of northern and central Ireland, for there were many tuatha that

the U

´

ıN

´

eill in particular sought to dominate; some of these constituted what

look like scattered remnants of earlier ‘tribal’ groupings – Gailenga, Luigne,

Ciannachta, for example – but the most notable were the seven tuatha of the

central north, known by the historic period as the Airgialla, that is vassal or

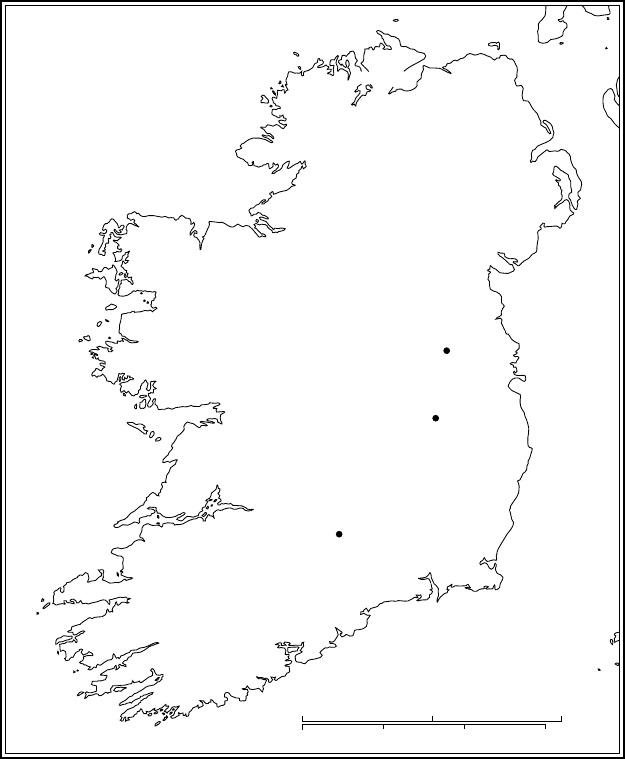

subject states (see Map 4).

The politics of the century or so after 560 have at first sight a bewildering

complexity. Cen

´

ogain fought Cen

´

al Fiatach fought D

´

el nE

´

el Conaill; D

´

al

el Conaill fought Diarmait mac Cerbaill of the southern U

´

ıN

´

nAraide; Cen

´

eill

al nAraide fought Cen

´

ogain; Cen

´

(Ardgal’s nephew); D

´

el nE

´

el Conaill fought

´

D

´

al nAraide; S

´

ıl nAedo Sl

´

eill) fought Cen

´

al Riata and D

´

aine (southern U

´

ıN

´

el

nE

´

ogain, and so on. There is, however, an overall pattern: this is first the

simple pattern of increasing U

´

ıN

´

eill success against allcomers, and secondly

the pattern of survival of the more successful U

´

ıN

´

eill branches, eventually

symbolised by holding the kingship of Tara. The later sixth and early seventh

century is a period of frequent and evenly balanced conflict between U

´

ıN

´

eill

and Ulaid rulers; now one side is successful, now the other; now one branch

tries an alliance, now another; until the 637 battle of Magh Roth. Hence

Diarmait mac Cerbaill from the south, king of Tara, was defeated in 561 by

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

242 w endy davies

0 50 100 miles

ULSTER

Cenél

Conaill

CONNACHT

MUNSTER

LEINSTER

Airgialla

Cenél

Cairpri

Uí

Maine

Uí Briúin

Uí Fiachrach

Uí Dúnlainge

Uí

Cheinnselaig

Thomond

Clann

Cholmáin

Síl

nAedo

Sláine

Eóganacht

Chaisil

Eóganacht

Locha

Léin

Cenél

Dál

Riata

Dál

nAraide

Dál

Fiatach

Kildare

Cashel

O

s

r

a

i

g

e

U

L

A

I

D

Tara

nEógain

0 50 100 150 km

Map 4 Ireland

Ainmere of the Cen

´

el nE

´

el Conaill acting with the Cen

´

ogain at the battle of

Cuil Dreimne, a conflict instigated – apparently – by St Columba, cousin of

Ainmere, whose protection of the Connachta to the west had been violated;

27

Diarmait was finally killed by the Ulaid overking, Aed Dub of the D

´

al nAraide,

in 565. This was the time when Ulaid rulers made expeditions east across the

27

Annals of Ulster s.a. 561;cf. Vita Columbae iii.3, and pp. 71–4.