Fouracre P. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 1: c. 500-c. 700

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

253 The Celtic kingdoms

0

0

50 miles

50

40302010

10 20 30 40 60 70 km

DYFED

Meifod

Llangollen

? CADELLING

Chester

Gower

Llandaff

Llancarfan

Ergyng

Ariconium

ANGLESEY

G

W

Y

N

E

D

D

?

R

H

O

S

?

M

E

I

R

I

O

N

Y

D

D

?

C

E

R

E

D

I

G

IO

N

?

C

Y

N

D

D

Y

L

A

N

G

w

e

n

t

P

O

W

Y

S

GL YWYSING

? BRYCHEINIOG

? BUILTH

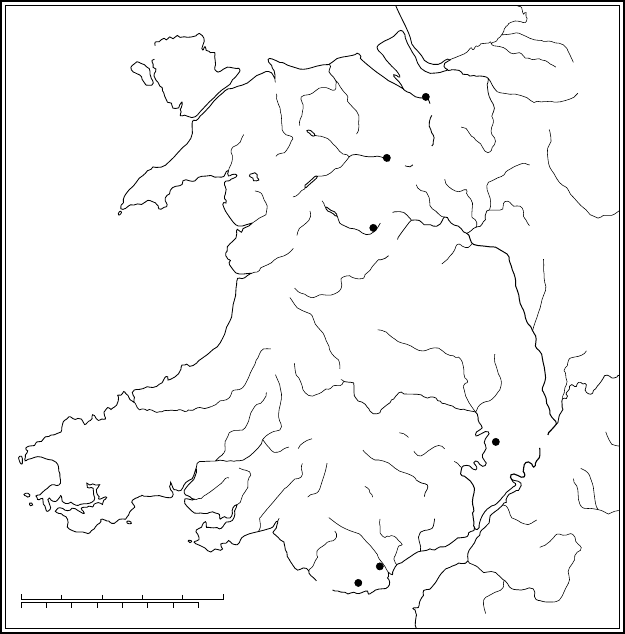

Map 6 Wales

the framework for the exploitation of the land – and the land continued to be

exploited (for it was, of course, good arable).

63

The sixth century is still very

hazy, although we know that by then a complex of independent kingdoms had

been established, that some were very small and some larger, and that some –

Gwynedd especially – had kings who were regarded as unusually powerful.

We also know that political power was already dynastically transmitted, from

father to son through royal families; that the concept of kingdom was strongly

territorial: it had borders, physical boundaries, and the land had to be defended;

that kings tended to have a military comitatus,a warband; and that, though

they had little to do with government, they were expected to be just and be

63

Davies (1978), esp. pp. 24–64, and (1979b).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

254 w endy davies

involved in making good judgements. In the seventh century, by contrast, we

can at last perceive something of the dynamic of the political process.

In the seventh century a new, larger kingdom was created in the south-east,

the kingdom of Glywysing, and the smaller kingdoms of the late sixth century

gradually lost their independent identity and were absorbed. Shortly after 600

Meurig ap Tewdrig, a new leader of unknown origin, began to be active in

the area of the lower Wye, and over the course of the seventh century he and

his family came to dominate virtually the whole of modern-day Gwent and

Glamorgan. This was achieved partly through marriage alliances – perhaps

to the Gower ruling family and certainly to the Ergyng family – and partly

by military conquest. The rulers that lost often continued to live on (and

off ) their old personal properties, but their status declined: no longer kings,

they became instead leading aristocrats. By the second quarter of the eighth

century there is no trace of the tiny kingships, and the successors of Meurig

had acquired personal properties all over his kingdom. By the mid-eighth they

looked set to establish fiscal, administrative and governmental institutions

for a political unit that must have been as self-contained and as notable as

Strathclyde.

64

By contrast, the kings of the north-west played politics on a far larger stage

and became involved in long-range raiding into the English midlands and the

far north of Britain. Just as the Gododdin poem claims that British warriors

came from far and wide for the defence of Rheged, so we can see kings like

Cadwallon and their followers travelling from Gwynedd to Hexham. Cadwal-

lon has left a deep impression on the historiography of the seventh century

since he was used by Bede to characterise the treacherous Britons: ‘although a

Christian by name and profession ...a barbarian in heart and disposition’.

65

He fought with the pagan king of the English midlands, Penda, against the

Christian Northumbrian Edwin; after Edwin had raided Anglesey, Cadwallon

rushed to midland England and then to northern Northumbria. Although

these were hit and run campaigns, they did mean that Gwynedd kings were

involved in the politics of the whole island of Britain. Not for nothing was

Cadwallon’s father, Cadfan, recorded in a seventh-century inscription as being

‘the wisest and most renowned of all kings’.

66

In north-east Wales, and the central marches, the principal trend was one

of curtailment and confinement by the English. In 616 Anglian leaders won a

major battle at Chester, which gave them control of the city and the Cheshire

plain.

67

This may well have displaced the Cadelling and certainly confined

64

Davies (1978), pp. 65–95.

65

Bede, HE ii.20; Historia Brittonum c.64; see also Thacker, chapter 17 below.

66

Nash-Williams (1950), no. 13.

67

Annales Cambriae s.a. 613;Bede, HE ii.2.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Celtic kingdoms 255

the nascent kingdom of Powys to the Welsh hills. Farther south the family of

Cynddylan seems to have lost control of Shropshire in the mid- or late seventh

century, for the Mercian kings seem to have been running the west midlands by

700. Later poetry regarded this defeat as disastrous for the family: Cynddylan’s

sister Heledd was left at the Wrekin bewailing the loss of her brothers.

68

So

here too, the Welsh were confined to the hills; a ruling family lost its capacity

to rule; a kingdom collapsed; and this may well have given the Cadelling the

opportunity to become established in the eastern parts of mid-Wales. Meifod

and Llangollen became the Powys heartland, rather than Chester. In all this it

was contraction and confinement that the English effected, not incursion. In

many ways the seventh century is the period of the establishment of the Welsh

border, and of the western limits of English political control (although the status

of the north and northern border remained uncertain for a couple of centuries

more). Despite Edwin’s long dart into Anglesey, it is not characteristically a

century of English raids into Wales; that was to come, with considerable and

repeated force, in the eighth and ninth centuries.

It really is impossible to characterise trends in internal Welsh politics in this

period. We can certainly note the English opposition in the seventh century,

and the definition of the ‘border’ (or border area), but we know far too little of

the sixth century to say much about it and not enough of the seventh to make

much sense of it except in very limited areas. The establishment of Glywysing,

and demotion of the petty kings of the south-east, is perfectly clear; so is the

range of interests of the Gwynedd kings; and the collapse of the Shropshire

kingdom. At best we might say that a number of petty kingships are lost – they

just disappear (unlike the Irish situation) – and the process of creating larger,

more structured kingships begins, with potential governmental responsibilities

and potential administrative frameworks. The possibilities were there but they

had not yet been implemented.

c ornwall and brit tany

Loss of territory to English control is as characteristic of Cornwall and Devon

as it is of eastern Wales in the seventh century. In 600 both counties lay

within a single kingdom of Dumnonia, a kingdom which probably also initially

included western Somerset and Dorset; by 700 that kingdom was confined to

present-day Cornwall. In 658 the West Saxon king Cenwalh was fighting on the

River Parrett in Somerset; by 690 there was an English monastery in Exeter; and

in 710 the West Saxon king Ine was making land grants near the River Tamar,

68

Davies (1982a), pp. 99–102; see Rowland (1990), pp. 120–41, for a slightly later dating.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

256 w endy davies

the traditional eastern boundary of Cornwall.

69

Thus, quickly and irreversibly,

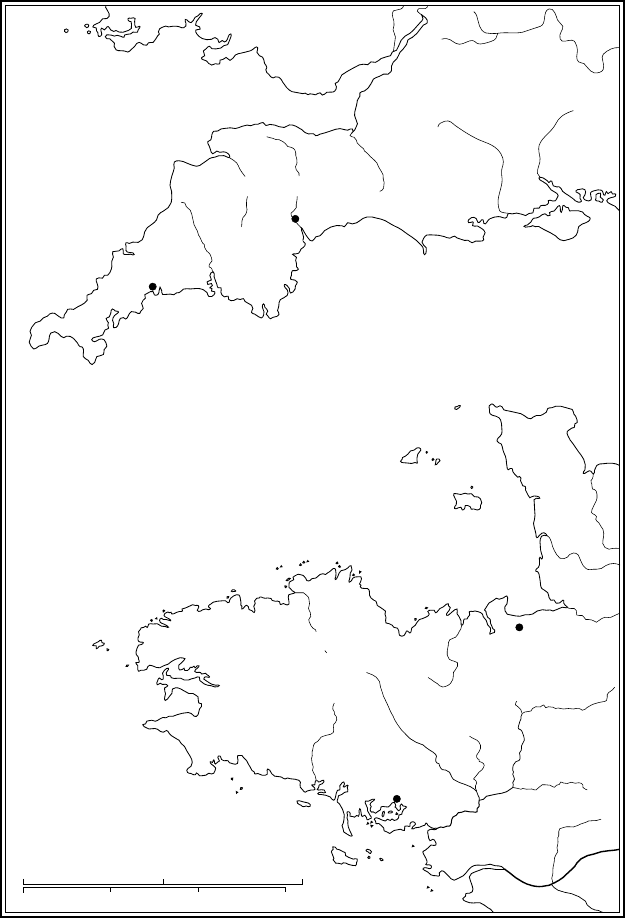

Dumnonia was reduced by more than half its former territory (see Map 7).

As might be expected, we do not know anything about the creation of early

medieval Dumnonia, but it was quite clearly in existence – and not new –

when Gildas was writing in the mid-sixth century; he referred to its king,

Constantine.

70

Like the kingdom of Dyfed in south-west Wales, the name of

this unit perpetuated the name of the Roman civitas, that of the Dumnonii,

and its origin may also have been to do with the continuation of a Roman

unit of local government. It is notable that its early sixth-century king bore

avery famous Roman imperial name: the rulers of Dumnonia seem to have

been influenced by the Roman tradition. Moreover, episcopal properties seem

to have continued undisturbed through the late and post-Roman period and

this may also have been true of secular landownership. It is likely, however, that

there was a little Irish settlement to disturb north Cornwall and south Devon,

for there are stones inscribed with the Irish ogham alphabet there.

71

Everything suggests that this kingdom was a monarchy, and by Celtic stan-

dards an unusually large one. There is never anything to suggest that there was

other than a single king, and that power was transmitted dynastically; Con-

stantine had two royal males murdered, presumably to reduce the possibility

of rival claims for the kingship. St Samson came across a property-owning

‘count’, who clearly had some influence over the local population; there may

have been several such men within the kingdom; we cannot know if they were

agents of the king or quasi-independent notables.

72

There is a suggestion in a ninth-century text, the Breton Life of Paul Aurelian,

that at least one king of Dumnonia ruled on both sides of the English Channel:

the early sixth-century Conomorus (Cynfawr). It is worth considering this

possibility seriously, although there is far too little contemporary material to

find sufficient corroboration. It is quite clear from linguistic evidence that

people from Cornwall and Brittany were in close contact in the early Middle

Ages: the languages were indistinguishable until the tenth or eleventh century,

and shared the same sixth-century and later changes. The (admittedly late)

genealogy of the Dumnonian kings includes a Kynwawr in the generation

before Constantine, a name which is a likely corruption of Cynfawr; and an

inscribed stone from Castle Dore in east Cornwall commemorates the burial

of one Drustanus, son of Conomorus; so there would appear to have been an

early sixth-century Cynfawr in Dumnonia. South of the Channel we have the

evidence of the Life of Samson for the appearance of a ‘tyrant’ Conomorus

69

See Thacker, chapter 17 below.

70

Gildas, De Excidio cc.28–9.

71

Pearce (1978), pp. 82–92, 165;Okasha (1993), p. 19; Thomas (1994), p. 331.

72

Vita Samsonis i, c.48.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

257 The Celtic kingdoms

R.

Par

r

e

tt

Exeter

Dol

R

.

T

a

m

a

r

C

O

R

N

W

A

L

L

DUMNONIA

DUMNONIA

CORNOUAILLE

POHER

VENETI/

BRO WEROCH

R

.

O

u

s

t

NAMNETES/

NANTES

RIEDONES/

RENNES

R

a

i

ne

R

.

L

o

i

r

e

Castle

Dore

0

0

50

50

100 miles

100 150 km

Vannes

.

V

i

l

Map 7 Cornwall and Brittany

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

258 w endy davies

in northern Brittany, sometime in the period 511–558, who killed the local

‘hereditary’ ruler Jonas and displaced him until Jonas’ son Idwal was instated.

Nowitso happens that Idwal’s dynasty was associated with the Breton province

of Dumnonia. Is it possible that the British Dumnonian king went adventuring

across the Channel? And is it possible that this, or a similar adventure, is

responsible for the transfer of the name ‘Dumnonia’ from the island of Britain

to the continental mainland?

73

The fact that we cannot be sure about so major an item as cross-Channel

political connections emphasises how little material we have from or about

Brittany in the sixth and seventh centuries. There is some background of

Armoricans ‘in revolt’ against imperial authorities in the fifth century and of

people coming from Britain to settle in the peninsula. There were certainly

enough Britons on the continental mainland by 461 to warrant representation

by their own bishop in the diocese of Tours; and by 567 there were enough

of them in Armorica to be a significant cultural group, distinguished from

the ‘Romans’.

74

Continental writers who died in the last decade of the sixth

century had the habit of calling the peninsula Britannia.

ForGregory of Tours Brittany began at the River Vilaine, the river that

rises well to the east of Rennes, runs through the city and then south to the

coast, 30 kilometres west of the Loire mouth; the Roman civitates of Riedones

and Namnetes, which approximate to the medieval counties of Rennes and

Nantes, and the modern d

´

epartements of Ille-et-Vilaine and Loire Atlantique,

largely lie to the east of that boundary. From Gregory we know quite a lot

about the problems that the Bretons had with the Franks in the 560s, 570s and

580s.

75

The Franks claimed to rule Brittany: they marched into it, and pitched

their tents along the Vilaine; they formally handed the city of Vannes to the

Breton ‘count’ Waroch, in return for an annual tribute; they took hostages

and sureties. The Bretons for their part attacked Rennes and Nantes again and

again, seizing the grape harvest from the Loire vineyards and rushing back to

Brittany with the wine; Waroch kept ‘forgetting’, as Gregory so disarmingly

puts it, the agreements he had made. The interaction was clearly violent and

disruptive. But it was equally clearly limited to quite a small area in south-east

Brittany. Nothing suggests that the Franks ever went to the west, or even the

centre, of Brittany (Gregory speaks of them reaching the Oust, a tributary

of the Vilaine, as if it were some far outpost) and they quite clearly did not

73

Vita Pauli c.8;Bartrum (1966), p. 45; Radford (1951), pp. 117–19; Vita Samsonis i, c.59;cf. La Borderie

(1896), i,pp. 459–69.Some of this material is worked into the later medieval story of Tristan; see

Pearce (1978), pp. 152–5;Padel (1981), pp. 55, 76–9.

74

See above, pp. 235–6.

75

Gregory, Hist. iv.4, 20,pp. 137, 152–4; v.16, 26, 29, 31,pp. 214, 232–6; ix.18, 24,pp. 431–2, 443–4;

x.9;pp. 491–4.See also Fouracre, chapter 14 below.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Celtic kingdoms 259

rule the peninsula in practice. Vannes may have been ceremoniously given to

Waroch after one expedition that reached it, but by 589 Frankish leaders could

only enter it by making an arrangement with the bishop; again and again they

had to negotiate with Waroch, even on one occasion sending Bishop Bertram

of Le Mans as a member of a deputation pleading for peace. This, then, seems

to have been the situation: Frankish kings effectively controlled the counties

of Rennes and Nantes, though the Bretons could be disconcertingly disruptive

there; they tried hard to get control of Vannes (the civitas capital of the Veneti),

sometimes succeeding, sometimes not; and they had nothing to do with the

rest of the country (see Map 7).

Within Brittany, that is west of the Vilaine, Waroch certainly did not act for

the whole region. He was the ruler of the Veneti civitas, the modern Morbihan,

known as Bro Weroc in the Middle Ages. There were other rulers in other

parts, and there were conflicts between them. Waroch’s father Macliaw and his

brother Iago had been killed by Theuderich son of Budic, a family that may

have come from the west (despite Theuderich’s Germanic name), while Jonas

of the north was killed by the tyrant Conomorus. At this period, the evidence

will only permit us to identify two units of rule – Bro Weroc and the northern

Dumnonia – and two other rulers, Budic’s family and Conomorus. Centuries

later we hear of a Cornouaille in the west and Poher west of centre and it is

traditional to associate the other rulers with these regions. This is by no means

impossible; but it is also possible, as suggested above, that Conomorus was

of south-west British origin and attacked from a base north of the Channel.

After all, the ruling family of (Breton) Dumnonia was restored in the mid-sixth

century and there is nothing to suggest successors to Conomorus ruling on

this south side of the Channel.

Whatever the number of political units within Brittany in the sixth century –

and all that we can say with confidence is that there were several – what type of

political authority did they exercise? Gregory of Tours is very firm in maintain-

ing that the Bretons did not have kings but had counts, and this terminology of

political authority is reflected and sustained in contemporary and later saints’

lives. Gregory’s approach is conditioned, of course, by his desire to present

Breton rulers as dependent on the Franks, and even the saints’ lives are prone

to represent the Frankish king as an ultimate authority; the Life of Samson,

written at Dol in north-east Brittany, undoubtedly reflects a Frankish perspec-

tive and has Idwal rather mysteriously imprisoned by Childebert and released

because of Samson’s representations to the Frankish king, allowing him to

return to Dumnonia and kill Conomorus.

76

It is reasonable to suppose that

literate and political Franks believed this, and the Frankish connection adds a

76

Vita Samsonis i, cc.53–9.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

260 w endy davies

dimension to Breton politics that is missing from other Celtic areas, but in prac-

tice although the terminology of political authority is largely one of dependence

it does not really matter what the rulers were called: they behaved indepen-

dently and acted like the kings of Strathclyde or Gwynedd or Glywysing. Their

power was transmitted dynastically: son followed father (Theuderich – Budic,

Idwal – Jonas, Waroch – Macliaw, Canao – Waroch), brother followed brother

(Macliaw – Chanao), and even the Life of Samson comments that Idwal stood

at the head of a long line that ruled Dumnonia. As for the shape of the political

units: the Roman background of civitas gave shape to Rennes and Nantes to

the east of the Vilaine and Vannes/Bro Weroc to the west, but farther west and

north the framework of civitates did not hold into the central Middle Ages and

it may be that immigration and/or a period of political control from Britain

gave shape to these areas.

77

Although there is some seventh-century archaeological material – metalwork

in east and west, coins minted in Rennes and Nantes – there appear to be only

two contemporary written references to seventh-century Brittany and they do

not allow us to characterise developments with any precision. The Frankish

Chronicle of Fredegar relates a tale about the Breton ruler Iudicael: once again

(or still) the Bretons had been raiding, and in 635 King Dagobert demanded

reparations and threatened to send an army if they did not materialise. Iudicael

made the journey to Clichy to discuss the situation and, although he refused to

eat at the same table as Dagobert, promised to make good the damage. Unusu-

ally for a Frankish source, the Chronicle calls him ‘king’ and presents him as

king of Brittany as a whole.

78

This should not lead us to suppose some move-

ment of Breton unification between 590 and 635: the fuller documentation of

the eighth and ninth centuries makes it quite clear that Brittany was politi-

cally fragmented until the middle of the ninth century; and, within Brittany,

Iudicael and his family were firmly associated with the region of Dumnonia.

Ninth-century tradition relates Iudicael to Idwal (of the Samson Life), and

Idwal to Riwal (his great-grandfather), the supposed founder of Dumnonia.

79

It therefore seems likely that Frankish rulers had more influence in northern

Brittany, and used their contacts there in an attempt to bring pressure on as

many Bretons as they could. (This is consistent with the Childebert/Idwal story

of the Samson Life and the long conflicts between Dumnonia and the rulers

in the Morbihan.) This certainly did not solve Franko-Breton problems for,

according to the Prior Annals of Metz, the Austrasian mayor Pippin II defeated

77

Dumnonia at least in part reflected the territory of the Coriosolites, but may well have extended

farther west; see Galliou and Jones (1991), p. 80, for a recent map of civitates.

78

Chronicle of Fredegar iv.78.65–7, also Fouracre, chapter 14 below.

79

La Borderie (1896), i,pp. 350–1.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

261 The Celtic kingdoms

Bretons among others in 688 and the old-style raiding and border warfare was

still continuing in the eighth and even ninth centuries, although in a rather

different political context. For the most part we simply do not know what was

happening in Brittany in the seventh century.

some concluding thoughts

Despite the unevenness of the available source material there are some genuine

comparisons to be made between Celtic areas in the sixth and seventh centuries.

There are, of course, some similarities: these are regions which had polities

with little or no governmental function, whose rulers had no means of regular

communication within and across the polity; they had a tendency to throw

up kingdoms, nevertheless; and extraordinarily strong dynastic interests in

rulership. It is very striking that ruling families are entrenched all over the Celtic

world from the moment that we begin to perceive what was happening; many

lasted for generations and some lasted for centuries. But there are differences

too between Celtic areas, and these need stressing lest the label ‘Celtic’ be

thought to imply some spurious homogeneity. Kingdoms were common, but

although there was nothing of the size of Visigothic Spain or the Byzantine

Empire there were considerable variations between them. Most Irish tuatha

cannot have been much more than 15–20 kilometres across; kingdoms like

Strathclyde or Glywysing were more like 80–100 kilometres across, and the

Breton polities a little smaller; while early British Dumnonia must have been

at least 200 kilometres from end to end. Kingship cannot have been the same

sort of experience in all of them. It was overkingship that created the dynamic

of politics in Ireland, perhaps assisted by the relative ease of movement across

the country and certainly fed by the availability of easily dominated surplus

produce. Overkingship may have been a factor in political relationships in

early Pictland, but it certainly was not so in Cornwall or Wales nor among the

Bretons in Brittany. Perhaps because of this, by 700 the Welsh kingdoms look

poised to develop more complex political institutions, as the Pictish kingship

did in the eighth century.

Overall, however, the inhabitants of the island of Britain suffered in this

period from Irish and English expansion, through both settlement and political

conquest. It is difficult to determine how much settlement was still going on

in the sixth century, but there was probably some – for example, in south-

west Scotland in one case and in the English midlands in another. Conquest

and military activity proceeded apace, by the Irish in western Scotland and

by the English in eastern Scotland and western Britain. Though their Scottish

adventure turned out to be short-term, the confinement of the British by the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

262 wendy davies

English is one of the major political developments of the seventh century. This

may seem like an old clich

´

e, but it is still true, whether we are regarding the

reduction of Dumnonia or the disappearance of Rheged.

There was, finally, movement between Celtic areas, quite apart from the

long-ranging military expeditions of Diarmait mac Cerbaill or Aed

´

an mac

Gabr

´

ain, Cadwallon ap Cadfan or Waroch son of Macliaw. It is quite possible,

as both Welsh and Breton tradition has it, that a significant part of the migration

of British to Brittany took place in the mid-sixth century and there was clearly

plenty of coming and going between south-west Britain and Brittany for the

next 150 years and more. There was also coming and going between northern

Ireland and western Scotland in the years before Magh Roth, and even then

the traffic did not stop completely, as it tended to do with the coming of the

Vikings. Some Celts travelled to England and to the continent beyond Brittany.

But these were mostly monks and clerics, and most were Irish. In the end, the

most striking migration, and the one that had the greatest consequences for

Europe as a whole, was of decidedly religious and not political character.