Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

KEITH CHAPMAN

56

electricity from biofuels, including waste incineration, the recovery of methane-rich biogas

from landfills and sewage gas from sludge digestion.

Many governments have paid lip-service to the promotion of renewable energy in the

UK. The oil price-shocks of the 1970s provided a boost when renewables were seen as

potential contributors to an energy strategy aimed at reducing dependence on expensive

imported oil. The then Labour government initiated a programme of research and

development co-ordinated by the newly created Energy Technology Support Unit (ETSU).

Assessments of the potential for wind and wave power in the UK were published in 1977

and 1979 respectively. These were followed by various small demonstration projects, but

there was little government encouragement during the 1980s until the issue of global warming

appeared on the political agenda. This provided a different reason to reconsider renewable

energy sources which offer a potential route to the achievement of the UK’s target reductions

in greenhouse gas emissions (see Chapter 18). The legislation privatising the electricity

supply industry provided an opportunity to address the problem of greenhouse gases and, at

the same time, to promote renewable energy. The 1989 Electricity Act introduced the Non-

Fossil Fuel Obligation (NFFO) in England and Wales. This requires the regional electricity

companies to purchase a specified proportion of their electricity from non-fossil fuel sources.

Nuclear power was regarded as the most important of these sources, and the NFFO was

originally conceived to protect the market share of the state-owned nuclear power stations.

The objectives of the NFFO were, however, widened by allowing the government to require

a certain ‘tranche’ of electricity to be generated from renewable sources. This ‘tranche’ is

effectively subsidised by the ‘Fossil Fuel Levy’, which is a tax on the electricity bills of all

consumers. Thus the NFFO and its equivalent in Scotland, the Scottish Renewables Obligation

(SRO), now form the central mechanism for supporting renewable energy in the UK.

Recognition of the principle that renewable energy needs subsidising to encourage its

development in the longer term is a very important departure from previous government

practice and there are indications that the Energy Review scheduled for completion in 1998

will endorse this principle by committing the government to annual subsidies of up to £300

million.

Despite these trends, the contribution of renewables to total energy consumption

was only 0.3 per cent in 1995. This is lower than any other EU country and contrasts with

the overall EU average of 6 per cent and a corresponding figure of 25.4 per cent for

Sweden. These statistics reflect the combined legacy of an abundant fossil fuel resource

base and an early commitment to nuclear power. This legacy suppressed the development

of renewables, and an assessment of the geographical impact of any increased future

contribution of these technologies to energy supply in the UK must, necessarily, be

speculative. The largest renewable energy projects in the UK are the hydro-electric schemes

established in Scotland as early as 1895. There is little prospect of further developments

of this type, and the frequently discussed tidal barrage schemes for the estuaries of the

Severn and Dee are unlikely to be reactivated. The future of renewable energy almost

certainly lies in small-scale, localised schemes. Some clues as to the probable patterns

may be gained by reference to the results of the introduction of the NFFO and the SRO.

These are evident in the outcomes of a series of Renewables Orders or rounds starting in

1990. Companies proposing to establish renewable energy generating projects bid to supply

electricity under a Renewables Order and the various proposals are approved or rejected

by the Office of Electricity Regulation (OFFER), which specifies the price to be paid for

ENERGY

57

electricity generated from different categories or ‘bands’ of technology. The identified

‘bands’ relate to electricity generated from wind, hydro, waste incineration, sewage gas,

landfill gas, and ‘biofuels’ such as agricultural and forestry wastes. The applicants for

Renewables Orders include a wide range of interests extending from the major electricity

generators (i.e. National Power and Powergen), which have been especially active in

developing wind farms, to small, project-specific groupings. Figure 3.15 indicates the

locations of 388 separate projects contracted under the five NFFO rounds to 1995.

‘Contracted’ projects are not necessarily implemented, but the maps may be regarded as

indicative of the spatial characteristics of renewable energy sources. The different sources

have distinctive geographies. Wind and hydro projects tend to be associated with the west

of the country, reflecting environmental influences such as wind-speed, rainfall and relief.

By contrast, various schemes utilising waste products such as landfill and sewage gas are,

for obvious reasons, urban-oriented. Despite these differences between the various sources

of renewable energy, they share the common characteristics of being small-scale and

widely scattered. These characteristics are obviously related in the sense that multiple

supply points are a logical consequence of limited output. They represent further

fundamental differences between renewable and fossil fuel energy sources other than the

familiar distinction based on long-term sustainability. The dispersed pattern implied by

Figure 3.15 represents a reversal of the dominant trend shaping the geography of energy

supply in the UK over the last thirty or forty years towards the concentration of capacity

into fewer, larger centres of production. It is, however, important to remember the minimal

contribution currently made by renewables to UK energy consumption. There is no doubt

that this contribution will grow, but great uncertainty about the rate of increase and,

therefore, about the size of this contribution over the next twenty to thirty years.

Conclusions

In 1979 UK oil production exceeded the output of coal in terms of energy equivalent for

the first time, and the country became a net exporter of oil in the following year. These

events underline the major changes which have taken place in the energy market since the

Second World War as the country has passed from almost total dependence on indigenous

coal, through a period in which imported oil became the principal fuel, to the beginning

of a new era of self-sufficiency based upon a more diversified range of energy sources.

These changes in the structure of the energy market have had important spatial

consequences as the country’s key primary energy nodes have shifted successively from

the coalfields to the oil refineries to the offshore fields and associated terminals. These

shifts have in turn resulted in new distribution systems linking energy sources with their

markets. Generally speaking, the scale at which these systems operate has increased through

time. The principal energy nodes usually served local and regional markets in the immediate

post-war years. This was certainly true of the coal and gas industries, and even the electricity

system provided little opportunity for inter-regional transfers at the beginning of the 1950s.

Despite improvements in the transportation of coal by rail, this fuel remains costly to

move by comparison with other forms of energy and, because of its dependence upon the

power-station market, much of its output is consumed on or adjacent to the coalfields

themselves. Distance is a less significant constraint upon the other fuels. National grids

exist for both natural gas and electricity, while pipelines enable petroleum products to be

KEITH CHAPMAN

58

FIGURE 3.15 Projects contracted under the NFFO, 1995

ENERGY

59

transported in bulk from coastal refineries to regional distribution terminals serving major

inland markets.

The significance of the market as the most important single influence upon the

contemporary geography of the energy industries is a sharp contrast to the traditional

attractions of the coalfields to certain types of manufacturing. Despite the greater mobility

of petroleum products and electricity, for example, the location of both oil refineries and

power stations has been strongly influenced by market considerations. The refining complexes

on the Thames and Mersey estuaries are well placed to serve the intervening axial belt of

population. Similarly, the distribution of power stations broadly matches the regional pattern

of demand, although local concentrations of capacity are related to the proximity of fuel

sources such as coal and natural gas.

The mobility which characterises contemporary forms of energy is, to some extent,

related to the costs of the fuels themselves. With the very significant exception of the

oil price-shocks in the 1970s, the real costs of energy have tended to fall over the long

term. More recently, privatisation has, for example, contributed to a substantial fall in

the prices of gas and electricity to consumers in the UK. Although superficially attractive,

such trends discourage conservation and sustainable patterns of consumption. Thus it

might be argued that substantial price increases are needed to promote a more

conservation-oriented society in which energy movements are minimised by adopting

the local supply/demand systems associated with renewable sources. It would, however,

be unwise to overestimate the political appeal of such an argument and a radical shift

away from the long-established dependence of the UK upon fossil fuels seems unlikely.

Nevertheless, the great changes which have taken place in the geography of UK energy

during the last thirty years emphasise the risks involved in making even the most cautious

predictions.

Notes

1 Proved reserves are those quantities which geological and engineering information indicates,

with reasonable certainty, can be recovered in the future from known deposits under existing

economic and operating conditions.

2 Applying a different set of assumptions, estimates of recoverable coal reserves in a report submitted

to the government in 1992 were as low as 700 million tonnes.

3 British waters incorporate the UK Continental Shelf over which the UK exercises sovereign

rights of exploration for and exploitation of natural resources. This area includes offshore areas

to the west of the UK as well as the North Sea.

4 Maximum recoverable reserves are the sum of proven, probable and possible reserves where

proven reserves are defined as having a better than 90 per cent chance of being produced, probable

reserves have a better than 50 per cent chance and possible reserves have a ‘significant’ but less

than 50 per cent chance of being technically and economically producible.

5 The National Coal Board adopted the title ‘British Coal Corporation’ in 1987.

6 The only exception was 1984 when substantial imports of fuel oil were made as a result of the

miners’ strike.

7 This estimate is made on a more restrictive definition of oil-related jobs than the 350,000 referred

to earlier, which includes indirect employment effects.

8 The long-established surplus of generating capacity of electricity demand in Scotland has also

discouraged CCGT investment.

KEITH CHAPMAN

60

Reference

Department of Trade and Industry (1995) The Energy Report (vol. 1): Competition, Competitiveness

and Sustainability, London: HMSO.

Further reading

Cumbers, A. (1995) ‘North Sea oil and regional economic development: the case of the North East of

England’, Area 27: 208–17.

Department of Trade and Industry (annual) Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics, London:

HMSO.

Department of Trade and Industry (annual) The Energy Report (2 vols), London: HMSO.

Department of Trade and Industry (1993) The Prospects for Coal, Cm. 2235, London: HMSO.

Department of Trade and Industry (1994) New and Renewable Energy: Future Prospects for the UK,

Energy Paper 60, London: HMSO.

Department of Trade and Industry (1995) Energy Projections for the UK: Energy Use and Energy-

related Emissions of Carbon Dioxide in the UK, 1995–2020, Energy Paper 65, London: HMSO.

Department of Trade and Industry (1995) The Prospects for Nuclear Power in the UK, Cm. 2680,

London: HMSO.

Fernie, J. (1980) A Geography of Energy in the United Kingdom, London: Longman.

Harris, A., Lloyd, G. and Newlands D. (1988) The Impact of Oil on the Aberdeen Economy, Aldershot:

Avebury.

Hoare, A. (1979) ‘Alternative energy; alternative geographies?’, Progress in Human Geography, 3:

506–37.

Hudson, R. and Sadler, D. (1990) State policies and the changing geography of the coal industry in the

United Kingdom in the 1980s and 1990s, Institute of British Geographers Transactions New Series

15: 435–54.

Manners, G. (1994) ‘The 1992/93 coal crisis in retrospect’, Area 26: 105–11.

Manners, G. (1997) ‘Gas market liberalization in Britain: some geographical observations’, Regional

Studies 31: 295–309.

Mitchell, C. (1995) ‘The renewables NFFO: a review’, Energy Policy 23: 1077–91.

Mounfield, P. (1995) ‘The future of nuclear power in the United Kingdom’, Geography 80: 263–71.

Openshaw, S. (1986) Nuclear Power: Siting and Safety, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Parker, M. and Surrey, J. (1995) ‘Contrasting British policies for coal and nuclear power 1979–1992’,

Energy Policy 23: 821–50.

Spooner, D. (1995) ‘The “dash for gas” in electricity generation in the UK’, Geography 80: 393–406.

Stevens, P. (1996) ‘Oil prices: the start of an era?’, Energy Policy 24: 391–402.

Trade and Industry Committee (1996) Energy Regulation, House of Commons Paper 50, Session

1996–97, London: HMSO.

Trade and Industry Committee (1998) Energy Policy, House of Commons Paper 471 (3 vols), Session

1997–98, London: HMSO.

Walker, G (1997) ‘Renewable energy in the UK: the Cinderella sector transformed’, Geography 82:

59–74.

61

Chapter 4

Earth resources

John Blunden

Introduction

The UK contains rocks which are representative of almost all the identified geological

systems, from the oldest which occur in the north and west and include many igneous and

metamorphic types, to the youngest which predominate in the south and east and include

the softer sedimentary rocks. Besides giving rise to a remarkably varied and often extremely

attractive range of landscapes these rock types provide an extensive source of mineral

products, some of which are widely mined or quarried and have important economic value

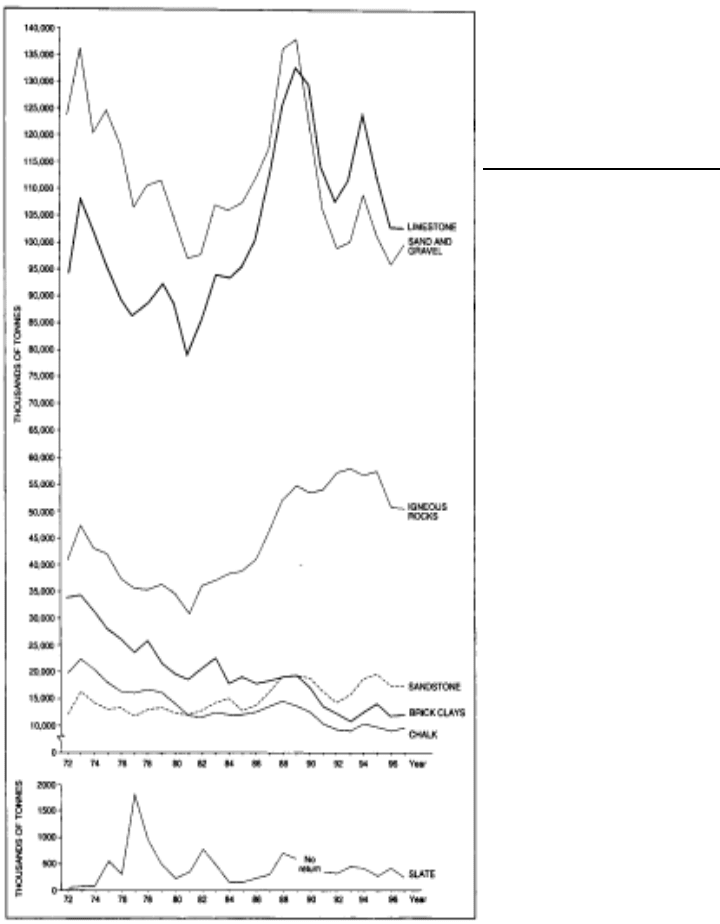

(Figures 4.1 a c). These extend from the ubiquitous aggregate materials, sand and gravel,

igneous rocks, limestone and sandstone; to other non-metalliferous minerals such as chalk,

brick clays and slate; to more localised non-metalliferous minerals such as china clay, ball

clay, gypsum and anhydrite, salt, fluorspar, barytes and potash; and to the metalliferous

minerals, iron, lead, zinc, tin, copper, gold and silver (Dunham 1979).

Minerals exploitation: a changing milieu

Little more than a quarter of a century ago the United Kingdom was thought to be about to enjoy

a period of unparalleled expansion in the exploitation of its minerals’ potential. Not since the

mid-nineteenth century when the UK had been a major world producer of copper, tin, iron and

lead and zinc had it been possible to envisage for the UK a situation in which minerals might

play such a key role in its economy (Blunden 1975). Experts, in reassessing the potential of

Cornwall, one of the country’s richest metalliferous regions in the last century, were able to

suggest that its then somewhat moribund economy would be transformed by a ‘considerable

renaissance’ in the production of tin and that as a result ‘the prospects for the national economy

as well as that of the South West of England could be exciting indeed’ (Eglin 1969).

JOHN BLUNDEN

62

FIGURE 4.1a Ubiquitous non-

metalliferous UK minerals:

production levels, chief locations

and utilisation, 1972–97

Source: British Geological Survey,

United Kingdom Minerals

Yearbook

Sand and gravel, igneous rocks,

sandstone, limestone

The use of aggregates by the

construction industry is notoriously

susceptible to the state of the

economy. Recent increases in the

consumption of igneous rocks,

sandstone and limestone are

indicative of the growing problems

associated with sand and gravel

production, though the extraction of

hard rock materials from traditional

sources is becoming increasingly

problematic. The substitution of

igneous material from remote

quarries is posited as one solution.

Some limestones, those of

greatest purity, are also extracted

for their chemical properties and

are used in a number of industrial

processes, including the

manufacture of soda ash, caustic

soda, organic acids and solvents,

dyestuffs and bleaching powders, as

well in the production of cement.

Chalk and brick clays

Both undergo secondary

processing, the former being a key

input to the manufacture of cement

and the latter the chief element in

brick-making. Although clays are

common, brick-making has become

concentrated on the Oxford clays of

the Peterborough and Bedford

areas. The production of both

reflect the state of the UK economy.

Slate

Found widely in the Grampian Mountains of Scotland, the Lake District, North Wales and Devon

and Cornwall, the number and the scale of workings has fallen dramatically as slate is no longer the

universal roofing material. Although still used in this role to a limited extent, demand is now largely

confined to architectural cladding. Penryhn (North Wales) and Delabole (north Cornwall) are the

most significant producers. However, large quantities of waste (some twenty times that of usable

product) remain at a number of sites and have a limited use as a filler in plastics and fertilisers, and

in the manufacture of roofing felt.

EARTH RESOURCES

63

Whilst at that time the traditionally locally traded low-cost building and construction

materials were experiencing unprecedented growth in output on the back of a demand for

new houses and offices and a rapidly expanding motorway programme, a different set of

factors were influencing those more costly minerals marketed internationally. Abroad, many

long-standing sources of supply appeared to be becoming problematic as reserves dwindled

or the political climate became more uncertain. At the same time new exploration techniques

were giving promise of the possibility of greatly increasing the UK resource base. This was

not merely in terms of reviving the fortunes of previously worked minerals, but also of

developing other non-renewable industrial minerals, some of which had made little or no

economic impact previously. Thus by the beginning of 1971, twenty-eight companies had

agents or staff geologists exploring eighty sites (Figure 4.2), ranging from one re-examining

the potential of the old Levant tin mine on the Land’s End Peninsula to another seeking to

evaluate copper deposits in Ross and Cromarty (Blunden 1975). All were also assisted by

government, first by investment grants and tax concessions and then in 1972 through its

Minerals Exploration and Investment Grant Act. In moving to replace the previous

arrangements the new legislation offered financial support of up to 35 per cent of total costs

for new exploration initiatives, leaving regional investment grants to play a major part in

helping to underwrite the costly early years of mining development and minerals production

(Rogers et al. 1985).

However, in the intervening period between the mid-1970s and the present day, other

exogenous factors have come to influence the exploitation of that resource base in terms of

those minerals that can be traded internationally. Further developments in methods of locating

and evaluating potential resources have achieved ever higher levels of sophistication and

have been applied in the 1980s in many developing countries (Andrews 1992) whose former

ambivalent political attitudes, particularly towards foreign investment, have undergone a

remarkable transformation. This has often been as a result of pressure from the International

Monetary Fund which sees mining development as an important tool in promoting economic

growth. Many countries, particularly in South America, are now offering mining companies

security of mining tenure; government joint ventures guaranteed through third parties; and

a prompt government response to, and assistance with, development plan proposals, including

those related to environmental controls. The result has been that newly discovered ore fields

have rapidly been developed and then brought into production, usually utilising surface

mining methods of the most capital-intensive and cost-effective kind (Gooding 1992).

But these intiatives have not been the result of the actions of the smaller, often national,

companies that characterised the early 1970s. They have been largely replaced by

multinational corporations operating at a global level and able to influence market conditions

and raise venture capital on the international finance markets. As a result they look to achieve

maximum economies of scale at large, long-life opencast operations, and, where possible,

in a local milieu relatively free from onerous environmental constraints (Radetski 1992).

This was a situation hardly likely to favour investment in the UK, with its rigorous system

of planning controls and where mining development, if approved, might at best be operable

only at the edge of profitability. Indeed, in the case of tin mining, when compared with the

extraction of the disseminated placer or alluvial ores by capital intensive open pit methods

in, for example, Indonesia and more recently Peru, its underground extraction in Cornwall

involving the working of vein deposits was bound to be a more costly operation. Under the

JOHN BLUNDEN

64

FIGURE 4.1b Localised non-metalliferous UK minerals: production levels, chief locations and

utilisation, 1972–97

Source: British Geological Survey, United Kingdom Minerals Yearbook

China clay

The UK, together with the USA, produces 60 per cent of world output. Seventy-five per cent is

used as a filler for fine papers. The rest is used to make ceramics and as a filler for rubber,

EARTH RESOURCES

65

plastics, and paints. China clay extraction is now coming under increased overseas competition from

substitute materials.

Ball clay

The UK may be only the world’s third largest producer but the quality of its ball clay is outstanding.

The main extraction area is located in south Devon with some additional workings in east Dorset.

Open pit working predominates, although there are some underground workings. Ball clay is used in

the manufacture of earthenware, tableware, tiles and sanitaryware.

Fuller’s earth

Used as a binder in foundry sands, in the bleaching process, for domestic water treatment and for the

drilling of oil wells; the primary source of supply is Woburn in Bedfordshire.

Salt

Heavily concentrated in Cheshire where five major corporations operate, substantial quantities are,

however, also available from the Cleveland Potash mine at Boulby. The UK is a major world producer.

More than 70 per cent of output is used in the chemicals industry in the production of chlorine, caustic

soda and soda ash.

Gypsum and anhydrite

Mainly worked in the East Midlands but also in Cumbria and Co. Monaghan, gypsum is used to make

plasterboard and plaster products. Production is around 6 per cent of the world total. Anhydrite, found

in association with gypsum, is used to make sulphuric acid.

Fluorspar

The UK, formerly a significant producer in global terms, still has a world presence even if it is rather

diminished. Demand for the product is closely associated with the construction industry and major

capital goods. Although it is extracted in Weardale in the northern Pennines, the Peak National Park is

a key production area.

Barytes

Like fluorspar, this mineral is often associated with lead and zinc and is therefore mainly worked in the

southern Pennines. However, Scotland now has a single producer at Aberfeldy. Although it has a

number of uses related to the production of ceramics and glass, and in one form finds its way into the

production of paints as well as a compound used for the medical examination of the digestive tract,

around 90 per cent is employed in the oil and gas drilling industries the activities of which largely

control its market.

Potash

Although in the world context, the UK is a small producer of a mineral vital to agriculture, output has

risen throughout the period. Extraction takes place solely in the North York Moors National Park at

Boulby, but the workings are underground and cause minimal disturbance to visual amenity.

Silica and moulding sands

Used in glassmaking and foundry mouldings respectively, the chief production areas for the former are

at Blubberhouses, west of Harrogate, Reigate in Surrey, Loch Aline near Oban and Alloa, and for the

latter in Cheshire.

Diatomite and talc

Both are mined for their unique physical and chemical qualities. Diatomite is used mainly as an insulating

material and in filtration processes, although if its quality is poor it can be employed as a filler in paints

and rubber. Talc is largely employed in cosmetics and as a dry form of lubricant. Both have been

produced in relatively small quantities from deposits in the far north and west of Britain.