Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Bridges

80

In early medieval Europe, tiles were most likely to show up on church

fl oors. Even without tin glazing or colors, there were ways to make them

decorative. Unglazed tiles could be molded into shapes that could inter-

lock to form a mosaic. Some church fl oors have elaborate mosaics of circles,

fl owers, diamonds, triangles, and hexagons or even more complex fl eur-de-lis

shapes. The natural variation in clay color was incorporated to make beau-

tiful patterns.

There was a simple way to create design with two colors. The potter or

tiler pressed reddish clay into a wooden mold with a carved design. When

the clay dried to the leather stage, lighter-colored clay fi lled in the imprinted

design to create a contrasting color, and then the tile was glazed and fi red.

This technique is called encaustic. Tiles could display checkerboards, re-

ligious symbols, heraldic designs, fl owers, or trees. Later inlaid two-color

tiles had carefully drawn pictures of kings and characters from the Bible.

During the 14th century, tile makers started printing designs onto tiles.

One technique used slip, a suspension of clay particles in water. The tile

makers made a die for the design, dipped it into the white clay slip, and

printed it over and over on tiles. This method was cheaper and faster than

stamping and inlaying. Late medieval tiles were also stamped with relief

designs carved into molds. They could be fi red unglazed or glazed yellow,

green, or brown.

See also: Houses, Pottery.

Further Reading

Campbell, James W. P., and Will Pryce. Brick: A World History. London: Thames

and Hudson, 2003.

Eames, Elizabeth. English Tilers. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992.

Gurke, Karl. Bricks and Brickmaking: A Handbook for Historical Archeology. Mos-

cow, ID: University of Idaho Press, 1987.

Riley, Noël. History of Decorative Tile. Hoo, UK: Grange Books, 1997.

Staubach, Suzanne. Clay: The History and Evolution of Humankind’s Relationship

with Earth’s Most Primal Element. New York: Berkley Books, 2005.

Van Lemmen, Hans. Medieval Tiles. Buckinghamshire, UK: Shire Publications,

2008.

Bridges

During most of the Middle Ages, rivers and streams did not have bridges at

all. Shallow places were fords where people, animals, and wagons crossed

up to three feet of water. Deep places had ferry boats, often with a rope

across the stream so the ferry, attached to the rope, could go back and

forth easily. Ferries were wide, shallow, square-browed boats with a good

Bridges

81

landing place on each side. Passengers would pay a toll to support the ferry

service.

The simplest bridges were designed for foot travel and packhorses over

small streams. Footbridges of wood were most common, but none have

survived into modern times. Simple stone bridges came in two kinds,

fl at and arched. Flat bridges used stone piers and a wooden road surface

that did not make use of arches. The timbers went from shore to pier to

shore; alternatively, the road surface could be slabs of stone. Arched

bridges, entirely of stone, were the best, and the development of bigger

and improved arched stone bridges occupied the period’s engineers.

Causeways were alternatives to bridges, especially when the body of wa-

ter was broad or marshy. One medieval causeway in England, across the

fen near Chippingham (one of Anglo-Saxon King Alfred’s homes), was

over four miles long.

Early medieval bridges were made of wood. London had two large

wooden bridges before the fi rst stone one was built. These bridges were

not wide by modern standards, but they were wide enough for carts to

cross, unlike those for foot travel and packhorses. None have survived,

nor do we have pictures of them. They must have used bundles of timber

pilings, braced like timber-framed roofs, to support the roadway. Timber

bridges could be made strong enough to carry traffi c, but they were vul-

nerable to fl ooding. In some parts of Europe, such as northern England

and Germany, ice fl ows in the spring put great pressure on bridge piers and

could take them down.

Bridges were defensive structures in several ways. If a city controlled its

bridge, it could keep an enemy from crossing. It could also use the bridge

to fence off the river so that if the enemy arrived in ships, their progress

was halted. Wooden bridges were easy to destroy in defense of a city. De-

fenders could burn or pull down a bridge to turn its river into a moat. If

the bridge still stood, attackers could seize it and use their advantage to

isolate the city.

Medieval engineers needed to develop bridges that were wider and

stronger as their cities grew. They began with the technology the Romans

had developed; some Latin texts were still available. The bridges themselves

still stood, especially in the Roman heartland, but some Roman bridges re-

mained in outlying places like England. Roman engineers had developed

several key techniques for bridges: waterproof cement, cofferdams, and

arches.

Cofferdams are temporary walls enclosing a portion of riverbed that

could be drained and used as a construction site. Using cofferdams, Ro-

man engineers could build large stone footings for bridge piers and dig

down to solid rock where possible. Medieval engineers also used cofferdams.

They drove iron -tipped logs into the riverbed like nails, close together,

Bridges

82

until there was a fi rm foundation in the soft riverbed. They built stone

piers as footings and often enclosed the area within the cofferdam, around

the pillar, and fi lled it with rubble. This island footprint for a pier was

called a starling in English. Once the work was done, the cofferdam could

be removed. With waterproof cement, the masonry would be sturdy

whether the stream fl owed directly around it or in times of fl ooding.

Arches transfer the load borne by the top of the arch (roadway) to the

foot of the arch (pier supporting bridge). The more circular the arch, the

more directly downward the weight is transferred. A shallower arch trans-

fers the weight outward, horizontally toward the pier, as well as downward.

A true semicircle arch is the most stable, but it is also smaller in span and

requires more piers to cross a river. Wider, shallower arches allow for fewer

piers but are weaker and require both stronger piers and more engineering

skill for calculating their strength. When a bridge has more piers, the river’s

space is more restricted, and in fl ood seasons the water will run higher and

threaten the bridge. Roman engineers learned to make piers somewhat

pointed facing upstream so the fl oodwaters would part around each pier

and not press on it as much.

In the 12th century, medieval bridge builders picked up the Roman

tradition and experimented with shallower or elliptical arches. They made

their piers pointed facing upstream, and often the starling around the pier

also was pointed. At the road level, the pointed area could be used in vari-

ous ways. Left open, but enclosed with a wall that led out to the point and

back, it became a place where foot travelers could stand when a wagon

took up the roadway. On a larger bridge, the pointed upstream area of the

pier was large enough to build a small chapel or defensive tower. Many

bridges had chapels for travelers to rest in or hear Mass before starting on

their way.

Bridges were expensive, long-running public works. Frequently, they

were built by private parties, such as the local lord or monastery. The

builders usually collected tolls for the upkeep. Because bridges were so

necessary, and so expensive, bishops often declared an indulgence for those

who would help. A dying man or woman who left money or farm ani-

mals for the upkeep or building of a bridge would have less time in purga-

tory after death. Those who were under long penances for sins could have

them shortened if they manually helped build or gave money to build or

repair a bridge.

In 1176, two notable bridge events kicked off a new era of building. In

London, a stone bridge over the Thames River was begun to replace an

older wooden one. The new bridge took over 30 years to complete. It had

20 arches, and since it took so long, each arch had to be freestanding in it-

self. It was a wide bridge for its time, wide enough for two wagons to pass,

and it had footpaths on either side of the road. A drawbridge stood to one

Bridges

83

side, permitting the wooden road to lift and let boats through. The center

had a chapel. During the Middle Ages, only a few houses were built on this

bridge, although London Bridge later became famous for having a com-

munity built on it.

Around the same time, a company called the Bridge Building Broth-

ers formed in southern France. These monks undertook to build bridges

and maintain ferries. Their fi rst building project was the bridge across the

Rhone River at Avignon in 1176. It was one of the outstanding bridges of

its time, extending to an island in the middle of the river and then to the

other shore. It, too, had a chapel on one pier; the chapel was dedicated to

Saint Nicholas and held the body of the bridge’s original founder.

By the late Middle Ages, some long urban bridges had several stories

of buildings lining the narrowed roadway. The Ponte Vecchio of Florence

had a long gallery—an enclosed walkway—connecting the Uffi zi Palace on

one bank and the Pitti Palace on the other. Because the roadway was not

wide to begin with, these buildings were cantilevered out over the water.

The Ponte Vecchio bridge had butcher shops on one side located so the

slops of the butchering process could drop directly into the river.

London Bridge kept as many as 60 employees busy every day. The bridge

had to be continually inspected and repaired, and its growing population

Florence’s Ponte Vecchio still has shops overhanging the Po River, as it did in

medieval times. (Mubadda Rohana/Dreamstime.com)

Bridges

84

of houses and shops required repair and management. The bridge em-

ployed carpenters, masons, pavers, plasterers, carters, guards, and a boat-

man. The bridge’s foot on the south side had a large house containing the

workshops of the bridge’s work force. It included stables for the horses and

dogs and a kitchen with a full-time cook for the employees. The bridge

even owned some meadows where hay for its working horses was grown,

so the bridge employed a few farmers.

See also: Cities, Roads, Wagons and Carts.

Further Reading

Boyer, Marjorie N. Medieval French Bridges: A History. Cambridge, MA: Medieval

Academy of America, 1976.

Cook, Martin. Medieval Bridges. Buckinghamshire, UK: Shire Publications,

1998.

Cooper, Allen. Bridges, Law, and Power in Medieval England, 700–1400. Wood-

bridge, UK: Boydell Press, 2006.

Harrison, David. The Bridges of Medieval England: Transport and Society,

400–1800. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Bronze. See Lead and Copper

C C

Calendar

87

Calendar

Calendar, in modern usage, means a booklet of monthly schedules of num-

bered days, often with an illustration. In the Middle Ages, calendar meant

the annual schedule of holidays, fasts, and feasts in honor of the saints.

Some days were fi xed and some were movable, calculated by the position

of the moon. Medieval calendars kept track of the moon’s position. While

modern calendars keep track of days within a month and help us remember

the commitments we have for each day, medieval calendars kept track of

years and lunar cycles. The organization of a month was an afterthought.

There were books that laid out the calendar, many of which were orga-

nized by month and included illustrations, like modern calendars. They were

known as books of hours, since their main function was to help the owner

know saints’ days so he could recite the correct prayers at the correct hours.

Books were too expensive to make disposable ones for each year until pa-

per and printing made it possible. Medieval calendars were intended to be

permanent. These books were lavishly illustrated. Each month’s page was

decorated, in the style of its time, with borders, calligraphy, and pictures. The

pictures usually showed ordinary activities on a typical day of that season.

On these beautiful calendars, peasants sled, skate, butcher, and carry wood

in the cold months. Ladies gather fl owers while teams of horses and oxen

draw plows and vintners prune vines in spring. The pictures fl ow around the

central calendar chart.

On the calendar chart of a book of hours, there were columns on the

left in red or black ink. One column gave the dominical letters: a, b, c, d, e,

f, g . The fi rst day of the year was a, the second was b, and so on. However,

365 days in a year did not divide evenly by 7, but left 1 over, so the next year,

the fi rst day would have to be b . In this way, the shift in days of the week

could be tracked. It was up to the calendar’s user to know how to interpret

the days that year; one year, all a days might be Sundays, and next year they

were Mondays. Two other columns gave the position of the moon and the

Roman numbered date, which was also based on the position of the moon.

The rest of the line told the user what day it was in the liturgical calendar,

often which saint was to be honored that day.

The medieval calendar was based on the Roman tradition of the Julian

calendar. The Julian calendar used 12 lunar months to track one solar year,

with irregular days spread out to keep it as even as possible. Medieval cal-

endars tended to use modifi ed Latin spellings: Januarius, Martius, Maius,

Julius, Augustus, October, and December had 31 days. April, Junius, Sep-

tember, and November had 30 days, while Februarius had 28. Februarius

had an extra day in leap years, as in modern times.

Charlemagne tried to introduce a new calendar of months using the Franks’

native language. His year began with renaming January as Wintarmanoth,

Calendar

88

and next was Hornung. The months then used the signifi cant events and

farm occupations of each stage in the seasons: Lentzinmanoth, Ostermanoth,

Winnemanoth, Brachmanoth, Heuvimanoth, Aranmanoth, Witumanoth,

Windumemanoth, Herbistmanoth, and Heilagmanoth (Holy Month, be-

cause of Christmas). The calendar reform did not last beyond Charlemagne’s

time and was never widespread. The church, centered in Rome, used the

Roman calendar, so the Franks adopted it.

Traditionally, people tracked signifi cant dates by the liturgical calendar. A

baby was born just before Martinmas; a fair was held on Saint John’s Day;

pilgrims would set out on Whitsun or Midsummer Day. Knowing these

saints’ days in order was a daily-life skill. The best-known ones were as well-

known as modern Thanksgiving, but lesser saints’ days could be memo-

rized in a poem designed to put them in order in a catchy way.

The modern system of counting numbered days through each month de-

veloped during the Middle Ages for business and record keeping. Bede used

simple numbers in his history of the English people. By the 14th century,

notaries simply wrote down the numbered day of the month. However, in

the books of hours, and offi cially, Europe followed the old Roman system of

numbering days. It was a complicated method, but it had the virtue of track-

ing the phases of the moon, which helped in calculating lunar-determined

feasts.

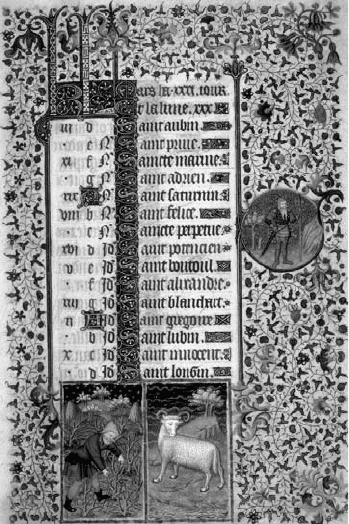

A medieval calendar showed the

saints’ days for the month, and it

could be used for many years in a

row. Days were not arranged in a

chart, as in modern times; they came

in a list, marked with letters and

Roman numerals so that days could

be calculated by the Roman system.

The day of the week mattered less

than the saint’s festival. The margins

around a calendar book (a book of

hours) were always painted with

elaborate designs and scenes of

daily life. (The British Library/

StockphotoPro)

Calendar

89

Romans divided their months into periods based on the phase of the

moon. There were 3 key days. Calends (or kalends) was the 1st day of the

month, the new moon. It was called calends because a Roman offi cial had

called out (Latin calere ) the start of a new month and time to pay interest on

debts. Ides meant the middle of the month, the time of the full moon, usu-

ally the 13th or 15th day. Nones was 9 days before the full moon. Only these

3 dates were distinguished, and all other days were named in relation to

them. If the ides of a month was the 15th day, then the 14th day was the

“pridie idus”—the day before the ides. Each day was named by working

backward to the next key day.

The medieval calendar used the Roman system. The month’s fi rst day was

Calends, and the next day, depending on the month, either IV or VI before

Nones, and on with a countdown to the Pridie Nonus and Nones itself.

There was then a countdown to the Ides: VIII, VII, VI, V, IV, III, Pridie

Idus, and Ides. The second half of the month counted down to the Calends

of the next month. Holy Innocents’ Day, which we call December 28, was

“ante diem IV Januariis.” On the chart in a book of hours, one column

tracked these countdowns.

Although there was an understanding that the fi rst of January began a

Roman new year, most medieval societies regarded a date in spring as the be-

ginning of the new year. In England and some other European countries,

the year began on the Feast of the Annunciation, March 25. In France, the

year began on Easter, although the date moved. Some people considered

the year to begin at Christmas. Only in the 14th century, as international

banking required standardization of dates, was the fi rst of January fi rmly es-

tablished as the start of a year. Traditional celebrations continued to be held

in spring until the 18th century.

One of the most contentious issues in the early Middle Ages was how to

calculate the day of Easter. In England, the Irish tradition of Saint Patrick was

not the same as the Roman tradition of the later-converted Anglo-Saxons.

Some English monasteries had been founded by Irish monks and contin-

ued to calculate Easter the Irish way. In 664, there was a national con-

ference, the Synod of Whitby, on how to decide when Easter would fall.

They voted to adopt the Easter tables drawn up by Dionysius Exiguus in

525 in Rome.

Dionysius (or Dennis) tackled the diffi cult problem of how to name years,

as well as how to calculate Easter. The Roman Empire had named years for

the emperor or consul, a system that ceased to work well after the fall of the

empire in the West. Dionysius, a monk who lived in Rome in the sixth cen-

tury, drew up a table showing the dates of Easter in many years. He iden-

tifi ed that he was writing it 525 years after the birth of Christ, or Anno

Domini—“in the year of our lord.” He used this approximation to rename

the years that had been named for Emperor Diocletian, who persecuted