Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cathedrals

110

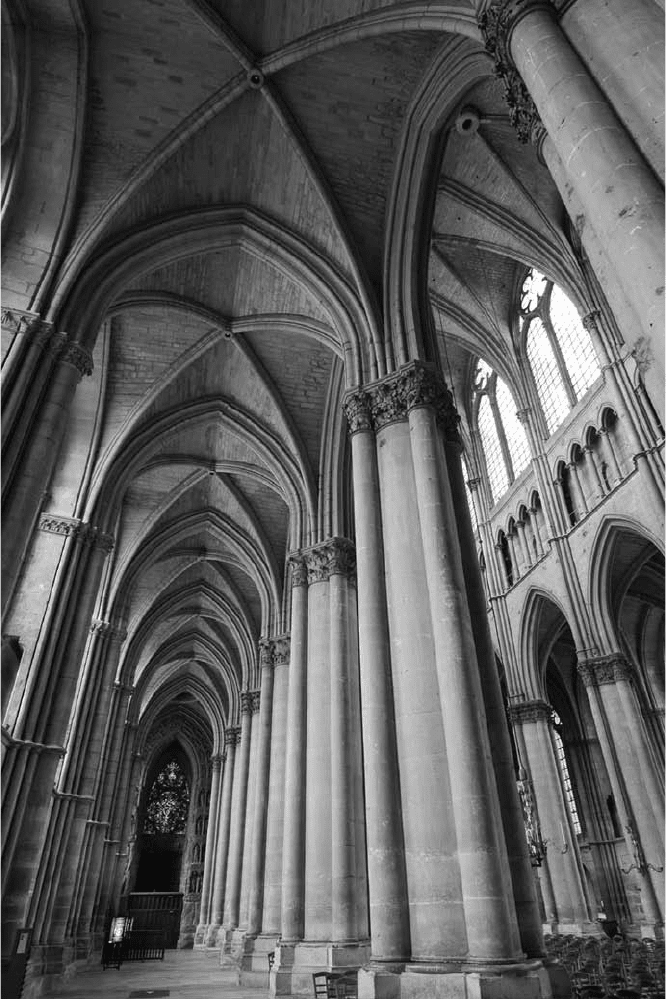

The key to Gothic cathedral building was the use of arches, ribbed vaults,

and external buttresses to hold the roof and walls without inner walls or col-

umns. Pointed arches are stronger than round arches; they can be of uniform

width while topping columns of different heights. They shift the weight di-

rectly downward onto their columns and piers. The walls of a Gothic church

were made up of a series of arches and columns, each layer smaller than the

last. The series of arches and piers was stronger than a solid wall and allowed

for more windows.

Ribbed vaults used a skeleton of stone arches that crossed in the middle

of the ceiling, forming X ’s, and rested on columns. The point where the ribs

crossed was called the boss and was carved as a circle. The ribs bore the ceil-

ing’s weight more effi ciently and required less heavy stone. Several arches

could rest on one column so that fewer columns were required to hold up

the ceiling. A typical ribbed vault had six arches: two transverse arches, two

lateral arches, and two diagonal arches that crossed in the middle. The diag-

onal arch was a refi nement of the groin vault’s joining of barrel arches going

in perpendicular directions, but the joints of a groin vault had not been load-

bearing arches. The ribbed vault placed skeletal, weight-bearing arches in

these places. Builders then fi lled in the spaces between the arches with cut

stone without needing massive timber forms.

Gothic ribbed vaults also used pointed, not round, arches. This gave

builders more fl exibility, as the arches could span wider or narrower distances

without affecting their height. Roofs could be built with a fan of pointed

arches leaning to one boss, roofi ng a large ambulatory around a reliquary.

Ribs could span irregular spaces, rather than just squares, octagons, and

circles. The ribbed vault of Canterbury Cathedral has extra ribs spanning

between ribs, forming smaller triangles and irregular hexagons. The most

elaborate rib vaults were called fan vaults, and the ribs were so many that

they could be individually thin and appear as delicate as lace.

The weight of a roof pushes a building’s walls outward. When a building

rises higher, the walls must be strengthened more—either by being thicker

or by being held in place. The Gothic church’s style did not permit walls

of such thickness that they would support the high roof because the build-

ers wanted the walls to be as open as possible to allow in more light. They

did not want supports on the inside that would block the view of the high

windows and ceiling. The outside walls of the church had tall support piers

leaned against them to buttress the walls from falling outward. These but-

tresses were built as a series of arches to transfer the roof’s weight to the

ground. They were called fl ying buttresses. They met the wall about one-

third of the height from the top.

The strongest fl ying buttress was itself a tower, built separately from the

cathedral and on its own foundation pier. As many as three arches connected

the tower to the outer wall of the cathedral. The most heavily buttressed

Ribbed vaults in Reims Cathedral hold up the vaulted ceiling with far less stone

than in previous construction methods. Three arches (transverse, lateral, and

diagonal) rest on each cluster of columns. The thin stone ribs lean on a round

boss, visible at the point of the X. The delicacy of the weight-bearing skeleton

allows maximum space for windows. (Claudio Giovanni Colombo/iStockphoto)

Cathedrals

112

buildings had a fl ying buttress between every large window, as many as 8 or

10 buttresses for the length of the church. These towers and arches were

decorated with steeples and arches.

Gargoyles were decorative spouts on a gutter system; in German they are

called Wasserspeiers, meaning “water-spitters.” They had to be long enough to

channel the water out away from the building, and, since everything on a

Gothic cathedral had to be decorated, they were sculpted, even if some also

contained pipes. When every other sculpture or painting in a cathedral was

solemn and holy, the waterspouts were a chance for sculptors to add a touch

of humor. They depict unusual or invented animals, like fl ying monkeys, or

show demonic-looking creatures with arms and legs. They grip the building

and lean out to spit water.

Mediterranean Style

Because Spain was caught up in the struggles of the Reconquest for most

of the medieval period, cathedral building was not as routine as it was in

France or England. Cathedrals were more isolated and more experimental,

more based on French churches and often attempting to blend elements of

style. The cathedrals of Burgos and Toledo come closest to the northern

models; both were begun around 1220 and were directly based on French

and German churches the bishops had seen on trips to France and Germany.

Italian cathedrals were somewhat different from those of Northern Eu-

rope. The Gothic style never caught on; they did not like the appearance of

fl ying buttresses. Churches were more likely to have a separate bell tower

(campanile) and baptistry. The baptistry was often octagonal; it could be

nearly as large as the main church. Italian cathedrals favored domes, and their

architects put most of their effort into building larger domes that would not

collapse. In Italy, the city communes, rather than kings or bishops, built ca-

thedrals. It was usual for the city to hold a competition for building designs.

Artists and masons built models, sometimes large enough to walk through,

which usually stayed on display until the church had been completed.

The cathedral of Milan was a blend of Romanesque and Gothic styles.

The cathedral is wide, with aisles of lower roof levels acting as architectural

support in place of fl ying buttresses. The external walls were decorated with

the intensity of sculpture that characterizes the French Gothic, and there are

a number of pointed-arch stained glass windows and a rose window. Or-

vieto’s cathedral uses murals, on both external and internal walls, to a far

greater extent than the northern cathedrals. The Byzantine tile mosaic tra-

dition continued in some cities that had more extensive contact with Con-

stantinople.

The Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence, had a competition in

1418 for how to build the dome of their half-fi nished building. The city’s

Cathedrals

113

problem was that the original designer had planned the largest dome in the

world without any idea how to build it. It was too large to use timber sup-

ports, the way arches had always been built. Filippo Brunelleschi won with

a model that was 12 feet tall and used thousands of bricks. The model even

included sculptures and paintings inside. Brunelleschi’s dome was double—

an inner ceiling dome and an outer weather-shedding dome. Both domes

were made of progressively thinner and lighter materials, such as tufa at the

very top. He was able to build it without any inner support in 16 years.

The dome’s stability depended on how the architect balanced forces of

compression and tension. He used herringbone brickwork that held itself

together and chains of stone and wood laid into the rising wall in circles to

keep it from buckling outward. Brunelleschi devised special cranes assem-

bled inside the dome to lift the blocks straight up. The masons working on

the project wore the fi rst safety harnesses on record as they worked at the

lip of the rising dome.

The fi nal keystone was the lantern structure above the top of the dome.

The lantern, which bridged a 19-foot hole that had been left in the main

cupola, was over 60 feet tall, providing some weather shelter for the win-

dow, and was capped with a hollow bronze ball and a cross. A bronze plate

set in the window turned the cathedral dome into a sundial, with the mea-

suring devices built into the fl oor.

See also: Bricks and Tiles, Church, Painting, Relics, Sculpture, Stone and

Masons.

Further Reading

Coldstream, Nicola. Masons and Sculptors. Toronto: University of Toronto Press,

1991.

Coldstream, Nicola. Medieval Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

2002.

King, Ross. Brunelleschi’s Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architec-

ture. New York: Walker and Company, 2000.

Oggins, Robin S. Cathedrals. New York: MetroBooks, 1996.

Parry, Stan. Great Gothic Cathedrals of France. New York: Viking Studio, 2001.

Prache, Anne. Cathedrals of Europe. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999.

Schütz, Bernhard. Great Cathedrals. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2002.

Scott, Robert A. The Gothic Enterprise: A Guide to Understanding the Medieval Ca-

thedral. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Stalley, Roger. Early Medieval Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

1999.

Stephenson, David. Heavenly Vaults: From Romanesque to Gothic in European Ar-

chitecture. Trenton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 2009.

Wilson, Christopher. The Gothic Cathedral: Architecture of the Great Church

1130–1530. London: Thames and Hudson, 2005.

Church

114

Chivalry. See Knights

Christmas. See Holidays

Church

The Roman Catholic Church and Europe’s Middle Ages can hardly be sep-

arated. The widespread, often fervent practice of a common religion uni-

fi ed a diverse region and gave it a common culture. The native cultures of

Europe shaped the church in turn and gave it a distinctly different shape

than under the Roman Empire. The same things can be said of the Eastern

Orthodox Church in Constantinople. It also unifi ed the lands of the East,

especially the Slavic regions, and the different political and military culture

of Byzantium shaped the Eastern church’s culture. Nearly all literature com-

ing from these regions during the Middle Ages refers frequently and cen-

trally to religion.

The fi rst great effort in the church was to convert the remaining pagans

in Europe. Missionaries went in all directions, sent by both centers of the

church. At the same time, the church defi ned its doctrines during the Middle

Ages in response to old pagan practices or to new ideas the church accepted

or rejected as heresy. The rift between Constantinople and Rome happened

in several stages but was complete by 1054. Around the same time, the Ro-

man church embraced the use of force when it commissioned the First Cru-

sade, a decision that linked religion and military power for centuries to

come. At many points in the Middle Ages, the Roman church in particular

developed ways of reforming and governing itself. This was demonstrated

most clearly in a succession of high-profi le church councils and in the many

monastic movements that began during this time. All through the medie-

val period, the church engaged in a prolonged struggle for power with the

monarchs of Western Europe, and this struggle gave birth to modern ideas

of the separation of church and state.

Medieval Missionaries

Monks from Constantinople went into the heartland of Eastern Europe,

where they converted Bulgars, Slavs, and other tribes. Bulgaria and the

Slavic regions became attached to Constantinople’s governance, doctrine,

and rites. Monks from Rome went to the English, Franks, Saxons, and Nor-

wegians. Ireland already had a Christian tradition from late Roman times;

they were converted largely by the preaching of Patrick, a Briton who had

learned their language as a slave. The spread of Islam into Persia and North

Africa between 600 and 700 prevented Christianity from spreading south

and east of its Mediterranean-centered homeland. Signifi cant conversions

took place only to the north and west.

Church

115

Missionaries generally went to the king fi rst, and, if the king accepted the

new faith, he enforced conversion for the rest. Faith was not viewed as just

a personal matter, but rather as the identity of a nation. When a nation be-

came Christian, the Pope or the Constantinople-based patriarch appointed a

bishop (known in the Orthodox church as a metropolitan) to govern the lo-

cal church, bringing it into the hierarchy of the larger church.

Some missions were peaceful, while others encountered hostility and dif-

fi culties. The Franks, in modern France and Germany, were converted fi rst

when their king, Clovis I, was baptized in 496. This early conversion of a

Germanic tribe made the next mission attempt easy and smooth. When Pope

Gregory’s emissary, the monk Augustine, went to the English coast in 597,

he found that the local king had married a Christian Frankish princess. The

mission was welcomed by the queen, and the fi rst church was established in

Canterbury. All the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms became Christian over the next

100 years.

The conversion of the Saxons, the Germanic tribe between the Franks

and the sea, was outstanding for coercion and bloodshed. Although the

Anglo-Saxon missionary Boniface had made inroads with his mission be-

tween 720 and 754, the forest -dwelling Saxons remained mostly pagan and

very warlike. Charlemagne attempted to conquer them and, after many frus-

trating setbacks, fi nally massacred thousands of Saxon prisoners in 782. He

declared a death penalty for refusal to be baptized. Charlemagne’s mentor,

the English monk Alcuin, rebuked him for forcing conversion, saying that

true faith could not be forced.

The conversion of the northern Germanic Danes, Swedes, and other Vi-

king peoples came about in stages. First, around 911, a group settled on the

northern coast of Frankish territory. Their leader, Rollo, agreed to become

a Christian and help defend the coast against other marauding Vikings. The

area he settled became known as Normandy—the land of the Northmen.

Its capital was Rouen. The Normans quickly adopted Frankish ways: reli-

gion, customs, language, and names. They remained unusually warlike and

became a dominant force in medieval Europe for years to come, taking a

leading role in the Crusades.

Between 994 and 1025, kings of Norway established Christianity as

their offi cial religion. There was no special mission to the Norwegians; they

learned the new religion from their old foes, the English. Iceland adopted

the new faith by 1000, but Sweden, the heartland of pagan worship, was still

not entirely converted by 1100. In both Norway and Sweden, there were

forced conversions and some executions for refusal to convert.

The Visigoths of Spain had become Christians in the last years of the

Roman Empire. However, they became converts to Arian Christianity, which

later developed into Catharism. Arian and Cathar doctrines were suffi ciently

different from Catholic doctrine that the two branches were incompatible.

Church

116

Eventually, the Arians agreed to convert to Catholicism, and the later wave

of Catharism was stamped out with a brutal Crusade.

By 800, the heartland of Europe had been Christian for at least several

generations. Still, the culture remained mostly conditioned by pre-Christian

tribal practices. Ideas of government, family, and relationships to other na-

tions were not much infl uenced at fi rst by the Christian religion. By the end

of the Middle Ages, the church was the foremost infl uence. Many of the

church’s teachings and rules were developed during the Middle Ages, as

culture and church interacted.

For example, Frankish nobles until Charlemagne’s time practiced easy di-

vorce, polygamy, and incest. Charlemagne himself divorced twice and was

married fi ve times. The church’s rules against divorce and marriage between

relatives grew much more stringent. No divorce was permitted, except for in

cases of adultery; no marriages were permitted not only between siblings or

cousins, but also between even distant cousins. (The aristocracy began to

use claims of too-close relationship as a means to divorce.) These rules were

proclaimed all over Europe and lasted into later centuries, although they

were fi rst framed to deal with the Frankish problem.

Ruling Hierarchy

The Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church, centered

in Constantinople, both used a hierarchical form of government modeled

after the Roman Empire. Overseers were appointed from above and had

absolute authority within their districts. In the Roman Catholic Church, lo-

cal priests had authority within each parish, which might contain several vil-

lages, a town, or only part of a town. A group of parishes was overseen by a

bishop, whose church was a cathedral. A region’s bishops were overseen

by an archbishop, and over the archbishops were cardinals. Over all of them

was the bishop of Rome.

The bishop of Rome, though technically a bishop, was the head of the en-

tire church because he claimed a direct descent of authority from Peter, one

of Jesus’s disciples. He was called the Holy Father of the Church: Il Papa in

Italian, and Pope in English. The Pope had absolute authority to appoint and

remove from offi ce, to forgive and condemn. Offi cially, the Pope in Rome

was also the overseer of the patriarch of Constantinople, who in turn over-

saw other patriarchs, metropolitans, bishops, and priests in the Orthodox

Church of the Byzantine Empire. In practice, the Pope had nothing to do

with the patriarch’s rulings.

While other bishops retained their real names, Popes developed a tradi-

tion of taking a new name. Clement, Gregory, Nicholas, Urban, and Paul

were very popular; they used Roman numerals to identify individuals. The

Pope also became the secular ruler of land in Italy—the Papal States. There

Church

117

was a palace in Rome, and later a castle at Avignon, France. Popes found

themselves in military struggles with other rulers; they had to resist invasion

as well as heresy. They were caught up in political battles as families and na-

tions tried to gain the power of the papacy by having one of their own

appointed or elected. While some Popes were devout men of prayer and

scholarship, other Popes were worldly rulers who despised religion.

The Pope’s authority was an evolving doctrine during the Middle Ages.

From the earliest centuries, the Pope took a leading role in the church, and,

by 865, Pope Nicholas stated in a letter that his authority came directly from

Peter and included all Christians. In 800, Pope Hadrian crowned Charle-

magne “Holy Roman Emperor” as a way of demonstrating the Pope’s power

over secular rulers. Still, a powerful king could appoint the Pope until a

church council in 1060 provided that Popes must be elected by the cardi-

nals. Kings still routinely appointed bishops, who also were secular rulers of

large tracts of land, until a prolonged confl ict between the Pope and the

kings of France, Germany, and England over this right fi nally resulted in a

compromise. Then, only the Pope could appoint bishops, but if they held

land from the king, they would do homage for the land as a non-priestly no-

ble would. The Pope gradually consolidated the rule of the church separate

from and above the nations.

On the other hand, the Pope’s power within the church was gradually

adapted during the Middle Ages. Civil war in Italy and a power play by the

French king led to a series of Popes based in Avignon, France, rather than

in Rome, between 1309 and 1377. Pope Gregory XI died shortly after he

returned to Rome, and the cardinals elected an Italian archbishop as Pope

Urban VI. Pope Urban proved to be mentally unstable and often violent,

and the cardinals met secretly to depose him and elect another Pope. Pope

Urban responded by appointing a group of new cardinals who would sup-

port him. From 1378 to 1415, there were two Popes, each elected by rival

groups of cardinals. This period is called the Great Schism. Europe was di-

vided in support of the Pope in Rome and the other Pope in Avignon. As

the years passed with no solution, and Pope after Pope died without giv-

ing in, the church at large began to seek a solution. A council made up of

bishops, abbots, scholars, and many others declared that the Pope’s power

came from the church and that the church’s members had the right to re-

move or appoint a Pope. Although this council still could not resolve the

Great Schism, their declaration began to curb and defi ne the Pope’s au-

thority.

Archbishops and bishops were powerful rulers in their zones of infl uence,

and they lived in palaces. They were often called “princes of the church,”

and their social rank was equal to dukes and earls. Since they had the power

to excommunicate secular rulers and place their lands under interdict, they

could sway the secular state to do what they wanted. They also presided

Church

118

over religious courts that had exclusive authority to arrest and try priests

or monks for crimes. This power was often a serious grievance to kings and

secular judges—some priests or monks became thieves and murderers, and

the church courts refused to bring them to justice. The 12th-century mar-

tyrdom of Thomas à Becket, archbishop of Canterbury, was over his insis-

tence that the secular courts could not try priests.

Priests who served at cathedrals as part of a religious order were called

canons. They were celibate, but they were not under a vow to withdraw from

the world like monks. Canons were installed, which meant they were liter-

ally assigned to sit in a stall in the choir. This was the canon’s assigned seat at

services, and it carried with it a stipend called a prebend (some canons took

in more than one prebend). At fi rst they lived in the cathedral’s chapter

house, but later they were permitted to live in private houses. Some canons

were even considered secular canons because they did not directly serve in

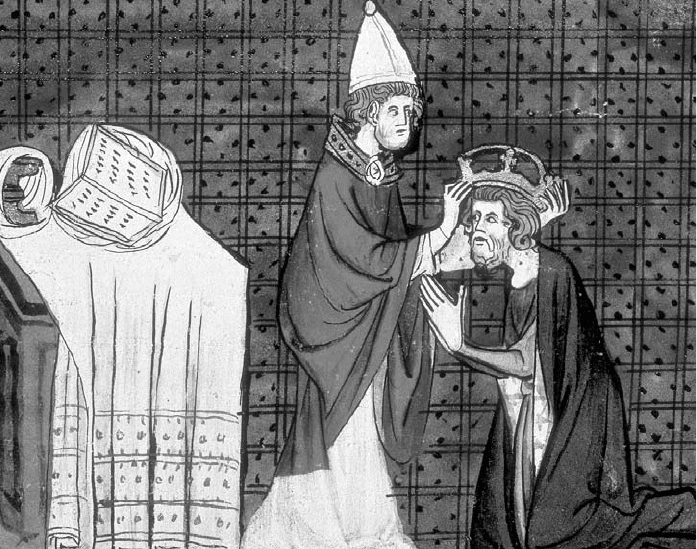

The medieval world’s political and religious parameters were set when the Pope

set the Roman emperor’s crown on King Charlemagne on Christmas Day, 800.

Charlemagne’s empire and successors had to be the Pope’s military and moral

supporters, while the Pope could claim spiritual authority above kings and emperors.

This European balance of power was strained during the period when two Popes

claimed authority. (The British Library/StockphotoPro)

Church

119

the Mass. Secular canons could continue to own private property and were

often very wealthy. They studied or taught at universities or administered

charities such as hospitals. Chapters of canons elected their own offi cers and

were self-governing, independent of the bishop. Secular canons could be

involved in many things that we would not expect from the church. In the

Flemish town of Tournai, the canons collected taxes on sales of alcohol.

Parish priests were at the bottom of the hierarchy, but they were the

church’s representatives to the vast majority of people. Some priests were ed-

ucated at cathedral schools or universities, but many were not. They were

educated in an apprentice-like training under a practicing priest and were

then ordained by the bishop. They memorized the prayers and knew how

to carry out rituals such as baptism, marriage, and burial. They led the cen-

tral worship service, the Mass.

While bishops often lived like princes, common priests lived closer to

their people. Some were married until the Second Lateran Council in 1139

declared that priests must all live as monks. There were riots in some cities

when this ruling was made known because these priests were part of their

villages and communities, and they had families who would be disrupted by

the new ruling. Many priests were forced to put their wives into convents in

order to remain serving as priests.

Monasteries were in a separate system. Each monastery had an abbot, or,

in the case of a convent for women, a prioress. A monastery was part of an

order, but this was less of a governmental structure. Each order had its own

rules and way of life and often a certain way of dressing. Abbots reported to

the Pope, instead of to the local bishop. The monastic system was not part

of the normal parish structure.

The Mass

Mass was celebrated many times each day in cathedrals and abbeys, but

usually only the monks and priests participated. The Mass was carried out in

Latin. In a cathedral or a monastic abbey church, a male choir sang hymns

in Gregorian chant, and the presiding priest preached a sermon that in-

structed the people in Christian living. The central event of the Mass was

the Eucharist, also called Holy Communion, the reenactment of Jesus giv-

ing bread and wine to his disciples.

Medieval Christians believed that the bread (called the host) changed to

the body of Jesus and the wine changed to the blood of Jesus in the most

literal sense. As the priest pronounced the words in Latin—“This is my

body”—he raised the holy wafer. There was a hush, and the church bell

rang. The people felt they were witnessing a miracle. They believed the

host had been turned into fl esh and blood so devoutly that there were sto-

ries of the wafer giving off drops of blood. Some monks, nuns, and other