Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Fairs

230

criers. The booths, stables, and houses on the fair grounds paid rent to the

count, and the wool-weighing service paid fees to the Knights Templar.

Lagny had a winter fair in January, and Bar-sur-Aube held a fair during

Lent. Provins and Troyes each had two fairs. Provins led off with a May Fair,

and then Troyes held its Hot Fair at Midsummer Day. Provins held the Saint

Ayoul Fair in September, and Troyes closed with the Cold Fair in November.

Each fair lasted 46 days. For the fi rst week, cloth was exhibited, and

then, for three days, buyers could purchase it. On the evening of the 10th

day, the offi cials proclaimed the cloth fair closed, and during the next

11 days, leather was for display or sale. The last 10-day period was for avoir-

dupois goods, the many goods sold by weight. Avoirdupois goods included

spices, wax, sugar, salt, dyes, grain, and wines. After the three sale periods

were over, money changers were open for business, and then the fair closed.

Merchants were given a period to restock and travel to the next fair.

The kinds of cloth sold at the Champagne fairs represented the wid-

est variety of available textiles. A merchant could buy thick blankets from

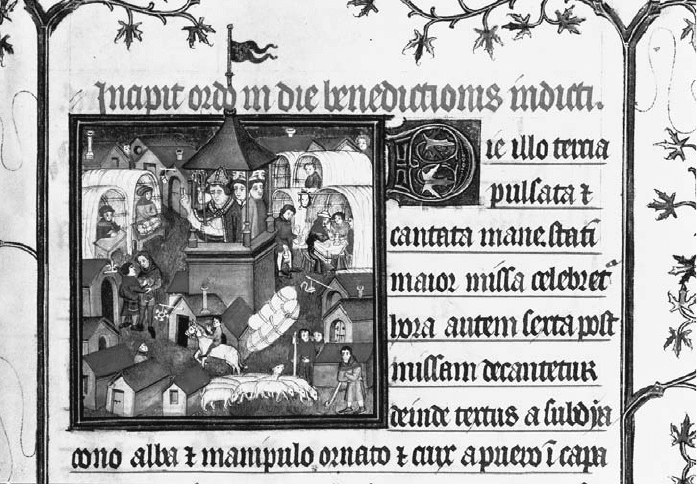

A medieval painter has crowded many details into a small space to give a sense of what

the annual fair was like. A central building holds the offi cials, shown as taller than

other men because they were more important. Around the margins, there are many

small outbuildings; some are permanent structures and others are temporary.

Countrymen bring in herds of animals while merchants show articles to customers

outside their warehouses. Men meet to discuss news and purchases. An annual fair

had a constant fl ow of people and animals for the weeks that it lasted. (Bibliotheque

Nationale, Paris/ The Bridgeman Art Library)

Fairs

231

Aurillac, velvet from Toledo, linen from Constance and from Champagne

itself, fi ne woolens from Flanders in three grades of quality, silk from Italy,

and brocade from Cyprus. Raw materials for the cloth trade were also im-

portant. Merchants sold raw cotton for stuffi ng quilted padding and dye

ingredients in wholesale quantities. Buyers could choose from brazilwood

and sandalwood, kermes and woad. Another wholesale product was alum,

a component in the dyeing process. Alum was mined in North Africa and

Asia Minor, so it arrived at the fairs from cities like Bougie and Aleppo.

The leather and fur portion of the fairs brought goods nearly as exotic.

There were leathers dyed red and blue, specialized Cordova leather used for

saddles, and sheepskins and furs from Norway and Russia. The leather and

fur trade was particularly important at the Lagny and Provins fairs. Provins

had a special hall set aside for furs and had tariffs for many different furs:

ermine, otter, marten, sable, cat (including domestic cats), and polecat (a

type of weasel, not a skunk).

The important cloth-producing towns of Flanders and northern France

formed a trading league to regulate the cloth trade at fairs. They were re-

quired to bring a certain amount of cloth to the Champagne fairs so in-

ternational merchants could always count on fi nding suffi cient quantities

for sale. They agreed to use the Champagne ell as the standard of cloth

measurement. Manufacturing towns like Bruges and Lille built houses in

the fair towns as warehouses and company headquarters. By the end of the

13th century, towns like Constance, Germany, and Lucca, Italy, also built

or rented permanent houses in Troyes. But the fairs of Champagne began

to fail after Countess Joan of Champagne married the French king Philip in

1284. The French king was interested in raising maximum taxes from the

fairs and imposed such high fees and tariffs that the trade could not sup-

port them. Venetian merchants used their galleys to open a sea trade with

Flanders, and the Champagne fairs had died off by 1320.

See also: Cities, Cloth, Holidays, Weights and Measures.

Further Reading

Cameron, David Kerr. The English Fair. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing, 1998.

Gies, Joseph, and Frances Gies. Life in a Medieval City. New York: Harper and

Row, 1969.

Kowaleski, Maryanne. Local Markets and Regional Trade in Medieval Exeter. Cam-

bridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Lopez, Robert S., and Irving W. Raymond. Medieval Trade in the Mediterranean

World. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

Pirenne, Henri. Medieval Cities: Their Origins and the Revival of Trade. Trenton,

NJ: Princeton University Press, 1969.

Wescher, H. The Cloth Trade and the Fairs of Champagne (Ciba Review 65). Basle,

Switzerland: Ciba Review, 1948.

Fasts

232

Falconry. See Hunting

Farms. See Agriculture

Fasts

Fasts alternated with feasts. Feasts were images of heaven, but fasts were

times of penance, when the body participated with the soul in remember-

ing sin and death. Christians were supposed to pray for forgiveness of sin

during these fast times. The key element of most fasts on the Christian cal-

endar was to abstain from meat and dairy products. Alcoholic beverages

were not forbidden, nor were spices and sweets. Only meat, eggs, and milk

products were forbidden. The poor were most likely to have bean porridge

on a fast day, although for many of them, every day was meatless. But for

the wealthy, fi nding interesting substitutes for the forbidden foods was a

serious endeavor.

The chief fast of the Christian calendar was Lent, the period of 40 days

before Easter, but there were many other fast days. Every Friday was a fast

day, in remembrance of Jesus’s death on a Friday. Wednesday, when Judas

accepted money to betray Jesus, and Saturday, in honor of the Virgin Mary,

were the two other weekly fast days. Ordinary weekly fasts were not seri-

ous affairs; the cook just had to serve fi sh. Four times a year, once in each

natural season, the normal fast days were observed with more seriousness;

they were then called Ember Days. In the spring, the Ember Days were in

Lent, and in the summer, they were just after Pentecost. They fell again in

September’s harvest season and last during Advent in December.

Lent was not the only long fasting season. Christmas Eve was a fast day,

followed by the feast of Christmas. Advent, the four weeks before Christ-

mas, was a fast period with the exception of a few saints’ feast days, such as

Saint Nicholas.

Lent lasted about six weeks. In preparation for Lent, which began on

a Wednesday, people ate the remaining fresh meat on Tuesday. They also

went to confession, which gave the day its name—Shrove Tuesday—but

it became known rather as Fat Tuesday or Carnival, the meat day. Not

only meat but also eggs had to be eaten up so they would not spoil and be

wasted. Egg-rich pancakes became a common Shrove Tuesday tradition.

During Lent, there was supposed to be only one meal, at evening, but

through most of the Middle Ages, the one meal was at midday, with a sec-

ond light snack at bedtime. Lent was a very long, hungry, dreary season for

all but the wealthiest and best fed, and even they were tired of Lenten foods

by the end. Although most medieval people took the Lenten fast with ex-

treme seriousness, some monasteries began to fi nd ways around the rules.

Lent was kept in the offi cial refectory, but not in the infi rmary, where the

Fasts

233

old and sick needed meat to remain strong. Many monks just went to the

infi rmary for supper.

The main substitute for meat on a fast day was fi sh. Medieval kitchens

dealt with a wide range of fi sh, both freshwater and saltwater. Recipe books

specifi cally mention herring, pike, bass, salmon, carp, cod, trout, perch,

tench, bream, haddock, whiting, whale, dogfi sh, mackerel, fl ounder, sole,

skate, cuttlefi sh, crayfi sh, porpoise, seal, lamprey, eel, oysters, lobster, crab,

mussels, and more. Modern classifi cation does not include seal, whale, or

porpoise as fi sh, since they are mammals, and, of course, shellfi sh are their

own class. But to a medieval cook, if it came from the water, it was a fi sh.

Beaver and otter were classed as fi sh for a time, and the tail of the beaver

continued to be permitted as fi sh. There were even fi sh that did not come

from water, such as newborn rabbits. Finally, legend told that the barnacle

goose, a migrating bird, was born from barnacles at sea and that it was a

sort of fi sh appropriate for fast days.

Recipes normally made with meat were stuffed with fi sh or nuts dur-

ing fast seasons. By the 12th and 13th centuries, cooks at large monaster-

ies, manors, and castles could prepare fi sh, eels, and shellfi sh in so many

ways that the table did not suffer at all in variety. Fish could not make up

all defi cits; recipes that called for milk or butter needed other substitutes.

Almond milk worked in most recipes; the nut was ground fi ne and mixed

with water, and its natural oils and nut meat formed a thickened white liq-

uid that cooked up somewhat like milk.

Large parts of Northern Europe depended on butter as a main cooking

fat. The alternative was meat fat, which was also forbidden, so it became

diffi cult to cook. In regions that depended on walnut or olive oil, this was

not a problem. During the later Middle Ages, the Pope began to permit

regions to purchase permission to use butter on fast days. The money often

went toward building projects, like cathedrals. Cheese was the other major

milk product; during Lent, dairies continued to make and age cheese, but

nobody was allowed to taste it.

A cook’s most serious problem with creating palatable dishes with fi sh

was the tasteless nature of most preserved fi sh. While aristocratic tables

could serve fresh carp, eel stews, or salmon, most people made do with

stockfi sh and pickled herring. Stockfi sh had to be pounded and soaked

and could not be made into anything more interesting than fi sh stew or

fi sh pie. Cod or herring preserved with salt made people very thirsty, and

Lent was often a time of greater drunkenness as diners tried to wash down

the salt with ale. Cooks rinsed and soaked salted fi sh repeatedly, and they

used spiced sauces to cover the taste. Good cooks could do well even with

salted, dried fi sh. A well-funded monastery could dine on roasted carp, her-

ring soup in almond milk, spiced cod pies, and a variety of alcoholic drinks

(from wine to cider to berry wines) to wash down the lingering salt.

Feasts

234

See also: Feasts, Fish and Fishing, Food, Holidays.

Further Reading

Fagan, Brian. Fish on Friday: Fasting, Feasting, and the Discovery of the New World .

New York: Basic Books, 2006.

Henisch, Bridget Ann. Fast and Feast: Food in Medieval Society . University Park:

Pennsylvania State University, 1976.

Scully, Terence. The Art of Cookery in the Middle Ages . Woodbridge, UK: Boydell

Press, 1995.

Toussaint-Samat, Maguelonne. A History of Food. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell,

1992.

Feasts

In medieval Catholic tradition, feast days alternated with fasts. Advent, the

weeks before Christmas, and Lent, the fast before Easter, led up to the most

important religious feasts. For the common people, whose daily diet was al-

ways more like fasting than feasting, a true feast was a great occasion.

Public feasts were times for showing off wealth or power. Humbler

people in the countryside put together feasts to celebrate weddings, and

guilds put on feasts to honor their patron saint. Knights, counts, and

bishops held holiday feasts at Christmas and Easter and on other feast days

in the calendar: the Feast of the Ascension, of the Three Kings, and of

other saints. They put on feasts to honor weddings, tournaments, and the

dubbing of new knights or to honor the visit of a noble guest. Kings put

on the grandest feasts of all, at times on a scale that staggers the modern

imagination. One medieval English king’s Christmas feast required 2,000

oxen and thousands of sheep, pigs, geese, fi sh, and eels.

For a great lord, such as a king or a duke, every dinner was a feast for the

many members of his household. Still, some occasions were more than a

large dinner. They were celebratory shows of wealth. They were occasions

for the lord’s cooks to show off their prowess and make their feast talked

about for miles around. As literacy and access to paper became more com-

mon, some guests at noble feasts took notes on the food as it was served. A

feast was the household’s greatest display of ingenuity and excess.

Guests were seated according to social hierarchy. One of the house’s se-

nior servants, called a marshal or an usher, was responsible for knowing the

exact rank and seating rules. A bishop was considered equal in rank with an

earl and sometimes was referred to as a “prince of the church. ” Archbish-

ops were equal in rank but had to be seated separately, perhaps for the rea-

son that one could not be elevated over the other. Secular lords also had an

exact hierarchy of seniority. Everyone had an assigned place at a feast.

Feasts

235

Real gold leaf made the crowns and cups shine in this book illustration showing King

Arthur dining with other royalty. Although the artist’s work is naive and simple where

human body positions are concerned, he has carefully drawn the white tablecloth with

graceful tucked draping. The table is properly set: each guest has a knife, a trencher,

and a cup. Guests at lower tables often shared cups; even at this high table, some

guests may be courteously offering to share. At each end of the table, there is a larger

gold article that may be the salt container. There are serving dishes, but the

13th-century artist has not given us any actual food; the snowy white cloth and

glowing gold dishes would leave a medieval viewer with no doubts of the unseen

food’s costly excellence. (Art Media/StockphotoPro)

Food at Feasts

At a feast, many dishes were prepared, but nobody expected to eat all of

them. They were carried around by servants, and guests chose which dishes

to sample. During the main meal, most dishes were meat or fi sh, with veg-

etables only as part of sauces or stuffi ng, if they were present at all. A feast

might include stuffed eel; meat pastries; fi sh or meat in a yellow, green, or

cameline sauce; and roasted meat. Each course that was carried around was

the same mixed array of meat dishes, but the variety changed. There was no

set plan of fi sh, meat, soup, or fruit. After the main courses, the table was

cleared and desserts were offered in a similar way. Spice wine and whole

spices, for digestion, could be part of dessert.

In Muslim Andalusia, an entertainer from Baghdad made a new feast

style popular. Food was served in courses: soup, fi sh, meat, desserts, and

fi nally a dish of nuts. He also introduced asparagus, which was popular

in Baghdad. The idea of orderly courses very slowly made its way north

and became the standard course plan in Europe during the Renaissance.

Feasts

236

During the Middle Ages, Europeans outside of Spain did not accept the

food course plan and continued to serve food in mixed courses.

The feasts of the wealthiest and noblest focused on presentation. Cooks

used bright colors, such as saffron yellow, to dye food unnatural colors. A

proper feast had yellow and green sauces, bright red meat compositions,

and blue puddings. The fi rst artifi cial dyes, borrowed from the science of

painting, came into use. A lichen, Gozophora tinctoria, turned red in the

presence of acid and created a brighter red than natural coloring from rose

petals or grape juice. Since many recipes called for meat, fi sh, or grain to be

ground and boiled, a cook could disguise a food’s nature with color very

easily. Fish is pale in color, so a cook could use a ground fi sh paste to make

bright red or blue jelly. He could arrange squares of colored fi sh or meat

jelly like a chessboard. Colored glazes could dress up a roast, pudding, or

pie in its last minutes of baking.

Many favorite dishes were meat pies, and pastry presented many oppor-

tunities for decoration. The simplest decoration was made from pine nuts

or pieces of pastry cut into leaves and fl owers. Cut pastry and colored glaze

allowed a cook to add a coat of arms to the top of a pie to honor a noble

guest.

Dishes were often made to look like something else: a fi sh concoction

made to look like a turkey, a rice and almond mix molded to look like a

fi sh, or a chicken dish made into a fl ower. The modern image of a medi-

eval feast with a boar with an apple in its mouth would be the simplest of

such visually stunning dishes. Castles, swans, and dragons made of food

could be present at a king’s feast. The nursery rhyme that speaks of “four

and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie” preserves a real trick royal chefs used.

The pie pastry, baked in advance with a hole in the bottom, was fi lled with

small live birds. The birds were not themselves baked, but, to the guests,

it appeared that they had been. As the pie was cut open, the birds fl ew out

into the rafters, and a real pie, perhaps embedded in the larger false crust,

was presented instead. Another favorite presentation piece was the giant

egg. A small animal’s bladder was fi lled with beaten yolks, and it was placed

inside a larger bladder fi lled with beaten whites. Tied shut and suspended

by a string, it was boiled to create a huge hard-boiled egg that could be an-

nounced as the egg of a mythical creature.

The showy plumage of swans, peacocks, and pheasants presented the

cook with a theatrical opportunity. The bird was fl ayed with skin and feath-

ers intact, and the fl esh and bones were drawn out. The meat was cooked,

often stuffed with other small birds, and replaced in the skin and feathers.

The feet were sometimes gilded with powdered gold or saffron. Wires and

skewers propped it into the shape of a live bird as it made its grand entrance

with sparks fl ying out from lighted camphor in its beak. The host or guest

of honor was often expected to make a vow at this point. Since these game

Feasts

237

birds might not taste as good as their feathers looked, some clever cooks

substituted roast goose for the peacock or swan.

By the 15th century, the most aristocratic feasts had become theatrical

events. A theme could be the Castle of Love, and the food would be staged,

displayed, or presented with scenery. The wine would fl ow in a fountain of

love, and the food could be staged in a wooden castle carried in on a plat-

form by four men. The food could include dishes shaped into castles made

from ground meat or pastry. A tableau of Venus and her court could be

staged between courses.

Dessert after a feast was always highly spiced. Medieval doctors believed

that the stomach cooked the food and that it must be kept warm in order

to do its work. Spices were hot and dry and would feed the stomach’s fi res

as it processed the meal. Dessert wine was sweetened and spiced. It was

called hippocras and could be spiced with cinnamon, ginger, mace, or other

popular spices. The servants also carried around a tray of spiced fruits or

candied whole spices.

Manners at Table

The key points of medieval feast manners were to honor those who were

highest in the social hierarchy and to keep from annoying dining neighbors

in a setting of very communal eating.

The great hall was set for a feast by arranging a high table that lay per-

pendicular to the other tables, at the narrow end of the hall, and usually on

a raised platform. This table—called a dormant table—was often the only

permanent table in the room, and it usually had a tapestry hanging behind

it. It was covered with a large white tablecloth. The lord’s chair sat in the

middle of this table, facing the hall. Guests were chosen for the high table

in accordance with their rank or with the honor accorded to them for the

occasion. The winner of a tournament would be honored at the feast even

if his social rank was usually inferior to the high table. Otherwise, the table

held only invited aristocracy. The best food came to the high table, and it

was served fi rst. At the high table, the lord’s place was set with a knife, and

other places could also have knives. In the 14th and 15th centuries, the

high places could have plates, and each place had its own cup. Food was

served individually at the high table, which had its own carver. The high

table had a special salt container called a nef; it really held salt but was also a

decorative centerpiece. The nef was made of silver or gold, and it was often

shaped like a ship (one kind of ship was called a nef) or a castle. The most

elaborate were large enough to have spare knives or small containers for

other condiments.

The temporary tables, made from boards on trestles, also had white ta-

blecloths. These could be used to wipe hands or even the mouth, unless a

Feasts

238

separate linen napkin was provided for this purpose. Each place setting was

a thick slice of bread as a plate. From the 14th century on, spoons made of

wood or horn were set at places as well. Guests brought their own knives.

In late medieval Italy, the aristocracy began to use small forks, but they

were not used anywhere else. One cup served for two place settings. Salt

cellars at the table completed the setup. Diners dipped the tip of a clean

knife into the salt bowl, and then put the salt onto the food on their indi-

vidual trencher.

The lower tables were most often arranged as a three-sided rectangle,

with diners seated only around the outside. Waiters could move in the mid-

dle, and all diners faced the high table. The table immediately to the right

of the high table was called the rewarde, and it was a place of honor. Both

tables closest to the high table were places of honor, and guests were seated

farther from the high table as their status dropped. The farther tables re-

ceived less attention from waiters and had to wait for food and drink. Me-

dieval people expected not to receive the same attention. Everyone knew

their rank, who was above and below them, and what they could expect.

Cups were made of a variety of materials during the period. The earliest

medieval drinking vessels of Northern Europe were horns with feet to make

them stand up. Early cups also included wooden bowls. Most later medieval

cups were pottery or silver. Glass was rarely, if ever, used for drinking cups

during this period. Great houses had fancy cups and spoons, fancy pitchers

and basins, and fi nely decorated tablecloths. In a period when there was a

great emphasis on conspicuous consumption and appearance, dishes could

have all kinds of decorations.

In the late Middle Ages, a wooden (or even silver) plate, called a trencher

like the bread it replaced, came into use among the rich. Before that, the

thick slice of bread was the only plate. Bread for a trencher had to be thick,

coarse, and dry. Its sole purpose was to soak up drippings and hold the

food, not taste good. At the end of a meal, the trencher—soaked in sauces

and drips and sliced up by the knife—could be eaten, but it usually wasn’t.

Bread for eating was provided at the table, separately, perhaps wrapped in

napkins. At the tables of the wealthy, trenchers were collected and given to

the poor, or sometimes they went to the hunting dogs’ kennels.

Male guests did not bring their wives to great feasts. The ladies present

were only of the host family and its attendants. In the late Middle Ages, the

restructuring of the hall to have a side-wall fi replace, rather than a central

fi re pit, meant the rooms immediately above and around the fi replace also

were warmed. The chief room just above the hall, accessed by a staircase,

was the lord’s private chamber. Ladies began to choose to eat separately

from the hall, in a quieter place, and eventually the upper chamber became

the place where the lord, lady, and select guests could eat more expensive

food than was available in the hall.

Feasts

239

To begin the feast, the lord, his family, and his guests at the high table

were seated fi rst, and grace was said while others stood at their places.

Guests at the lower tables could then sit down. Servants tested food for poi-

son and carried around water basins and towels for hand washing. Carvers

began serving food at the high table, and then servers brought platters to

the lower tables. A butler made sure that pitchers of wine or ale were circu-

lating to keep cups refi lled. At the fi nest feasts, a wine fountain in the center

of the room refi lled the servers’ pitchers.

Food came to the tables on platters sized for between two and six peo-

ple. Chargers were platters with food for two and were placed between

pairs of diners. The younger cut and served for the elder, or the man for

the woman, or the social inferior for the superior. Sauces came to the table

in bowls, and, since meat was already cut into pieces, the diner could put

meat pieces onto his trencher and then dip them into the sauce before eat-

ing. Soups were thick and had pieces of bread in them that could be picked

out with the fi ngers.

Most eating was done with the fi ngers, so they had to be kept clean. At

many feasts, servants periodically circulated with ewers and basins. They of-

fered to pour water over each guest’s hands, catching the water in the basin,

and then offered a towel. Some halls offered fi nger bowls of water scented

with roses. It was not acceptable to lick one’s fi ngers before putting them

into the common serving bowl to take out pieces of food. It was not ac-

ceptable to leave one’s spoon in the serving bowl or to take food with a vis-

ibly dirty spoon. It was not polite to scratch one’s head or any part of one’s

body while eating or to pick one’s teeth with the knife.

Bones and rinds went into an empty bowl called a voider or were tossed

to the fl oor. Rushes and fl owers were sprinkled on the fl oor to hide the

bones, but the lord’s hunting dogs often wandered the hall, picking up

scraps. Although the fl oor was not swept more than a few times a year, a

major feast called for a clean fl oor strewn with fresh herbs and rushes. The

servants cleared the tables between courses, and, by the dessert period, the

dishes and scraps were gone.

Many feasts concluded with drama or music and dancing in the center

of the hall. The castle’s kitchen and scullery would be jammed with dirty

cups, spoons, and platters, but the hall was free of its mess and noise.

See also: Beverages, Food, Furniture, Holidays, Kitchen Utensils, Poison,

Weddings.

Further Reading

Adamson, Melitta Weiss. Food in Medieval Times. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press,

2004.

Black, Maggie. The Medieval Cookbook. London: Thames and Hudson, 1996.