Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Funerals

270

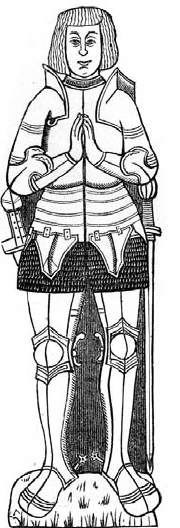

a house. These indoor graves often had brass plaques engraved with a like-

ness of the deceased as a memorial. Memorial brasses were a dominant art

form by the 14th and 15th centuries, and every family that could afford

them had brasses for every member. The engravings showed the deceased

in a pious position, standing or kneeling in prayer, and many are done with

careful attention to clothing, especially to the family’s coat of arms.

Atypical Medieval Burials

Not all burials followed these standards. There were exceptions toward

both more ritual and less. The aristocracy, especially royalty, needed special

treatment. At other times, such as during an epidemic, ritual could not be

kept up.

One of the fi rst examples of embalming in Europe was the burial of King

Charlemagne. His body was packed with spices and buried in the crypt at

his cathedral in Aachen. He was fully robed and seated on a golden chair.

The tomb was packed with more spices and perfumes. A descendant who

entered the tomb 100 years later found the king’s body still seated on his

chair, partially preserved.

Aristocrats were more likely to die when they were far from home, and

they sometimes left unusual instructions for getting their body back to the

The new availability of brass made affordable picture

memorials very popular for the lower aristocracy and wealthy

merchants. Although faces were probably represented only

approximately, brass engravers were meticulous in recording

details of armor and clothing. Much of what we know about

human appearance in the late Middle Ages comes from

memorial brasses. (Duncan Walker/iStockphoto)

Funerals

271

home cemetery. Sometimes they were embalmed, like Charlemagne, and

sometimes they were dismembered. Sometimes only the heart came home,

encased in a lead box. King Baldwin I, the Crusader ruler of Jerusalem,

died on campaign in Egypt and gave his cook directions for preparing his

body to make the journey back to Jerusalem. The cook gutted him of his

internal organs, salted the body inside and out, and seasoned his eyes, nose,

ears, and mouth with balsam and other spices. The body was rolled in a

large cloth and carried safely back for burial.

Embalming and dismembering could be done for reasons other than

travel. Aristocrats were more likely to be laid out for public viewing, lest

there be any mistake they were really dead. Salt, wine, and vinegar had

some preservative effect, but imported spices like cinnamon and pepper

worked better. The longer the body was to be displayed, the more embalm-

ing was required. King Edward I of England was displayed for four months

in 1307. Royal burials were expensive and showy. Spice embalming was

fantastically expensive, and therefore it was another way to display wealth

and power.

In the later Middle Ages, the price of spices began to drop. Minor noble-

men and even wealthy craftsmen could afford to buy them for their kitch-

ens, and the lesser nobility began to embalm bodies with ginger, cinnamon,

and cloves. Embalming may have been increasingly necessary as more peo-

ple were buried in chapels.

Nobles and kings were sometimes not only embalmed, but also dismem-

bered and buried in pieces. One obvious application of this custom was for

conveying some of the deceased home from a journey, such as a Crusade.

But, in other cases, members of the nobility asked to have themselves bur-

ied in different places. This way, they didn’t have to choose one place. Their

heart could be buried in one monastery, their entrails in another, and their

body in the royal cathedral. The offi cial church did not like this practice;

Pope Boniface VIII condemned dismemberment as barbaric and shocking.

His successor, however, found a way to sell licenses for permission to the

nobility.

Epidemics and famines disrupted customs, especially when the death

rate passed 10 percent. The worst was the Black Death plague during

1347–1352. It was heavily documented, especially in Italy, where paper

was more available and many people were literate. Funeral customs were at

fi rst attempted but then abandoned as the number of deaths increased. In

a proper funeral in Florence, female relatives and neighbors gathered at the

deceased’s house to mourn with the family. Men gathered at the front door

for the funeral procession, along with priests. They carried the corpse to

the church on a bier, on their shoulders, while singing dirges and carrying

candles. After a funeral Mass, the body was laid to rest in the churchyard.

A really fi ne Florentine funeral display was more elaborate and expensive.

Furniture

272

The funeral parade included banners showing the wealthy deceased man’s

many achievements and distinctions and incorporated men on horseback as

well as marchers.

During the plague, however, it became diffi cult to carry out the simplest

rituals. With whole families dying rapidly, there was nobody left to mourn,

and it was diffi cult to fi nd people to carry the bier. Priests, too, were dying.

By the peak of the plague, the city tried to maintain a service of removing

corpses for mass burials. Venice’s canal boat garbage removal service was

successfully put to use to carry away corpses. Bishops were reluctant to

consecrate new cemeteries, and some people began to use unconsecrated

land. The church fi nally blessed fi elds, and gravediggers began to make very

large pits. When the bodies piled up too fast, some were covered with ash

overnight.

Some communities became too disorganized to do more than bury the

bodies, but others maintained a mass ritual decorum as they could. In Lon-

don, even at the height of the plague, bodies were still laid in order, heads

to the west. In country cemeteries, families buried their dead on conse-

crated land, but they were forced to use common pits, and no ritual could

be observed when so many were dying at once.

See also: Beggars, Church, Guilds, Plague, Relics, Spices and Sugar.

Further Reading

Daniell, Christopher. Death and Burial in Medieval England. New York: Rout-

ledge, 1997.

Effros, Bonnie. Caring for Body and Soul: Burial and Afterlife in the Merovingian

World. State College: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2002.

Gies, Frances, and Joseph Gies. Daily Life in Medieval Times. New York: Black

Dog and Leventhal, 1990.

Pollington, Stephen. Anglo-Saxon Burial Mounds: Princely Burials in the 6th and

7th Centuries. Swaffham, UK: Anglo-Saxon Books, 2008.

Richards, Julian D. Viking Age England. London: English Heritage, 1991

Singman, Jeffrey. Daily Life in Medieval Europe. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press,

1999

Furniture

The Middle Ages did not put as much emphasis on furniture as later times

did. Furniture was simple and very durable; it was handed down to the next

generation and was rarely made or bought new. There were four basic fur-

niture functions: tables, chairs, beds, and storage chests. While furniture

styles varied some by region or across the period, there was not much in-

novation.

Furniture

273

Chairs were not common in the Middle Ages. Stools were the most com-

mon type of seating; peasant houses were likely to have a few basic stools.

Benches were also very common, since they could seat many people at

once. A manor hall typically had a number of benches that could be moved

to the side of the room or set up for a feast. They also doubled as beds, if

needed.

A real chair with a back and arms was a mark of distinction and was usu-

ally owned only by the lord of a manor or castle or the bishop or abbot of

a monastery. Some medieval chairs still in existence are shaped like a barrel,

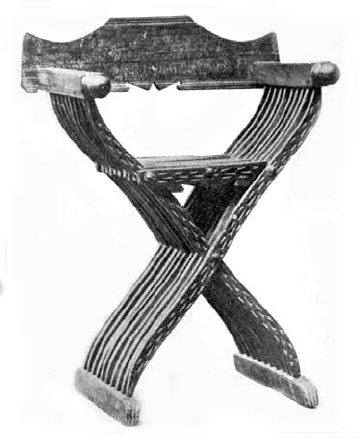

with round backs and arms above a solid base. Another popular style in the

late Middle Ages was a chair resting on legs that cross, as though the chair

might be able to fold. The Latin name of the chair was faldistorium, and

it is sometimes called a scissor-chair. Some of these chairs had no back and

may have been able to fold, while others only copied this style. Some had a

wooden seat and back, while others had a cloth seat and back so they could

actually fold. The scissor-chair appears to have been used only by royalty or

by bishops.

Since chairs were a luxury item, they were rarely plain. They were heavily

carved and frequently painted; the look of natural wood was not prized in

the medieval period. The greatest chair was a throne for a king or bishop.

The word cathedral came from the Latin term for the bishop’s throne, the

cathedra. Thrones were carved, painted, gilded, and padded with velvet or

embroidered cushions. Some thrones and throne-like tall chairs had a safe

built into the box below the seat.

Very few pieces of medieval furniture

survived into the present. As furniture

manufacture improved, nearly all of the

crude medieval pieces were recycled or

destroyed. Only well-made, remarkable

pieces, such as this scissor chair, were

kept long enough to join modern

museum collections. The scissor chair

was originally designed to fold, but most

medieval ones did not. They

were painted, gold-leafed, and

upholstered. ( Architectural Record 7,

no. 1 [1897]: 435)

Furniture

274

Tables were often portable and consisted of a board on trestles. Paintings

of feasts show clearly that the tables were resting on angled, crossed legs,

rather than straight ones like modern tables. In a castle or manor hall, they

could be set up and taken down as the size of the dining group changed.

In the 15th century, some feast tables were designed to fold; the legs were

not trestles, but the table could be stored in a side room. The key point for

a medieval table was to be rectangular and long so the hierarchy of the din-

ers was plain. At a feast, there was a high table and subordinate tables, and

etiquette dictated where each diner sat. The high table was the only perma-

nent, or dormant, table in the room.

In the later Middle Ages, there were some small occasional tables for

the wealthy. Paintings from the 15th century show small parties of diners

at square or round tables, as well as small round tables as furniture in other

rooms. Some stand on a single pedestal, and others have three legs. The

15th-century round tables that survived into the present include some with

marble tops. Round tables, though, were not common for dining. They

implied equality, rather than hierarchy. Some medieval paintings show both

Jesus and King Arthur eating at round tables with their followers, and the

message was clear to medieval viewers that these two great men were show-

ing the others equal honors, instead of sitting at a high table. Inns and

taverns may have begun using round tables before private houses, since

travelers did not know their social standing with each other, and a round

table encouraged them to sit anywhere.

Some functional rooms had worktables that were not on trestles. A well-

equipped medieval kitchen had a heavy table. Workshops, too, had sturdy

tables. The lack of tables in a house may have been caused less by a lack of

tables than by a lack of space. In a room that might shift its purpose accord-

ing to season and time of day, permanent furniture was in the way.

In the early Middle Ages, peasant beds were usually made on a sack of

straw. The sacks could be moved during the day, and it was easy to make an

extra bed if there was enough straw. Straw mattresses could be laid out on

benches or on the fl oor. Early Anglo-Saxon beds were wooden boxes made

to hold the straw mattress. In a castle, knights in attendance on the lord

may have used the hall’s benches for beds. Beowulf mentions that pillows

were stored in chests and brought out to turn the benches into beds. While

a bench may sound like a very narrow bed, pictures of medieval beds are al-

ways surprisingly narrow to modern eyes. A bed that looks large enough for

one will usually show two sleeping without much space to move around.

Images of later Norman-era beds owned by nobles suggest wooden beds

that looked similar to modern beds, with a head and foot and perhaps

knobs on the posts. As the middle class grew, simple wooden beds for straw

pallets became more common. At no time was it taken for granted that ev-

eryone had a real bed. Beds were often the most expensive thing a person

Furniture

275

owned, and they are usually mentioned in a will. If a bed is not specifi cally

given to a surviving spouse, child, friend, or hospital, there probably was

no freestanding bed. In some regions, beds were built into the walls, with

shutters or curtains.

Later medieval beds were often larger and grander. In the 13th century

and later, the beds pictured were four-posters made of wood and were al-

most always curtained for warmth and privacy. They had interlaced rope

springs and a straw mattress, which for nobility had a layer of feathers. Beds

had linen sheets, wool blankets, many pillows, and sometimes fur comfort-

ers. The earliest curtained beds did not have real canopies, but only ropes

or rods attached to the walls or posts for the curtains. By the 15th century,

grand beds had wooden frames above to hold the decorative curtains. When

the owners of such beds traveled to their other castles and manors, they car-

ried much of their furniture along. Stools and chests easily packed into the

wagons, as did the bed’s mattress, sheets, and curtains. The wooden bed-

stead probably stayed in the closed-up house; the cloth items were more

expensive and easier to steal.

Houses did not have closets built into the walls. Clothes were stored

in chests or hung on pegs. Chests were heavy and wooden and came in

all sizes, usually with locks. Large chests stored blankets; medium chests

stored clothing or furs. Small chests, also called coffers, stored personal

possessions or jewels. Chests were often carved and painted brightly. Large

chests doubled as benches in a chamber or hall. Most houses had a number

of chests, and even peasant houses probably had at least one.

Luxurious city houses had other pieces that were not known to most

homes. A cupboard was a storage chest on legs with doors that opened at

the front. It was usually carved and painted; placed in the main hall, it could

display fi ne pottery and glass. A writing table in the hall or in a cham-

ber permitted a scholar or businessman to work. Portable chandeliers pro-

vided evening light for those who could afford candles. Bookshelves may

have been the ultimate luxury furniture, since few individuals owned books

at all.

House furnishings also included many cloth items. Floors were never car-

peted outside of royal bedchambers, but imported carpets from the Mid-

dle East were hung on walls. Although windows were normally fi tted with

shutters, some city houses with glass windows used cloth curtains. Beds had

curtains as well as sheets and blankets, and benches and chests often had

cushions. For bathing and washing, there were linen towels hung on pegs

and rods. Houses above the poverty level covered dining tables with white

tablecloths. Walls were covered with painted fabric hangings, or tapestries

when they could afford them.

See also: Houses, Kitchen Utensils, Lights, Tapestry.

Furniture

276

Further Reading

Diehl, Daniel, and Mark Donnelly. Constructing Medieval Furniture. Mechanics-

burg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1997.

Diehl, Daniel, and Mark Donnelly. Medieval Furniture: Plans and Instructions for

Historical Reproductions. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1999.

Emery, Anthony. Discovering Medieval Houses. Princes Risborough, UK: Shire

Publications, 2007.

Gies, Joseph, and Frances Gies. Life in a Medieval Castle. New York: Harper and

Row, 1974.

Roux, Simone. Paris in the Middle Ages. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania

Press, 2009.

Singman, Jeffrey. Daily Life in Medieval Europe. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press,

1999.

Wright, Lawrence. Warm and Snug: The History of the Bed. Stroud, UK: Sutton

Publishing, 2004.

G G

Games

279

Games

Games appear in the medieval record mostly in illustrations of daily life,

such as in illustrated Psalters and calendars. We see children, teenage boys,

and ladies playing outdoor games of chase and tag. Other pictures show

men and women using board games or dice. A wide variety of games and

sports were played all over medieval Europe.

Gambling and Board Games

Medieval men used dice for gambling games. Dice had originated as

knuckle bones tossed in games of chance, but, by the early Middle Ages,

cubic dice with points were common. These dice were also made from

bone, but they were carved into cubes with the familiar modern arrange-

ments of dots burned into their sides with small branding irons. They also

tossed coins; in England, the sides of a penny were called cross and pile.

Playing cards came to Europe around 1400. They may have come

from India through Muslim Spain. The fi rst cards were hand painted and

only royalty could afford them. Early woodcut printing techniques made

cheaper cards available, and, by the middle of the 15th century, cards were

in common use even in England. There were two kinds, tarot cards and

playing cards, but we know little about how they were used. Cards did not

survive the ages well, since most were made of parchment or paper. Sur-

viving cards tend to be tarot decks with extra non-gaming fi gures included,

such as the Hanged Man, Death, and the Pope. Playing cards seem to have

used some fi gures still used today, such as kings and queens made of two

heads joined at the middle, rather than a full body. A 15th-century Italian

sermon mentioned other card fi gures: coins, cups, swords, and clubs.

There were several basic board games, and they seem to have been very

popular both at court and in city taverns. There were a few basic board lay-

outs, and different games could be played on the same board. In medieval

times, the checkerboard board was used for both chess and a game called

draughts, which was similar to checkers. They also used the backgammon

board and another board with diagonal lines connected to dots.

Chess originated in Muslim India; it came to Europe through the trade

routes of Persia and the Arab kingdoms. There is evidence that aristocratic

Europeans were playing chess by the year 1000. Chess came to England

after the Norman conquest of 1066. The game was popular all over Europe

through the Middle Ages. The pieces from the Indian game were modifi ed

to fi t the European world. Horses became knights, and the elephant be-

came a bishop or a standard-bearer. The camel, called rukh in Arabic, be-

came a tower but retained its name— rook in English. The vizier, the war

commander, became a queen in European play.