Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Latrines and Garbage

440

chute at night to get into the castle. Waste could also fall into the moat,

adding to the moat’s unattractiveness. If so, then the castle’s residents peri-

odically moved to another house while the moat was dredged.

The bigger, richer monasteries developed systems of simple plumbing.

They channeled rain or spring water through pipes into the buildings

and then used the wastewater to fl ush the latrines out. A typical “rere-

dorter,” the wing of a monastery devoted to latrines, was planned so many

monks could use the facility within a short time, since they lived on a sched-

ule. There was a row of wooden seats, separated by wooden walls for pri-

vacy, each with a shuttered window that could be opened for light and

air. Some monasteries could have used rags from old robes as toilet tissue,

while most others used hay.

Monasteries often had a source of running water, either piped in or by

means of a creek or diverted river channel. Monasteries with water sys-

tems used the waste from all other washing and cooking to fl ush out the

latrines, and a fi nal waste ditch carried all the wastewater off the property.

Sometimes, the wastewater went into the fi shpond, where algae fed on the

excrement; this was the fi rst simple sewage treatment system. More com-

monly, the sewage fl owed into the nearest river. Occasionally, it fed onto

someone’s property.

This castle garderobe has survived better than many since not only the closet and

chute but also the seat were made of stone. Daylight shines up through the hole,

which leads straight to the sea. (iStockphoto)

Latrines and Garbage

441

Town buildings with space to include a cesspit in the backyard did so. By

the late Middle Ages, city ordinances usually required that cesspits be lined

with stone to try to keep them from leaking into the surrounding soil and

contaminating wells. Some cesspits used barrels to line the shaft. About

every two years, they had to be dug out and the muck carted away. Digging

out cesspits was a regular trade for some laborers. The manure from each

pit was hauled out of the city in carts. It was a valuable resource for agri-

culture and was often sold as fertilizer after minimal processing.

A cesspit usually had a privy built over it. Frequently these were shared

among several families and could have more than one seat. When a large

city house had room for a cesspit, the owners sometimes placed a latrine at

the back of an upper room (a solar), with a pipe carrying the waste to the

pit outside. This was the closest thing to indoor plumbing. Anyone who

did not want to climb down the stairs or ladder to go outside to the privy

(or who did not have a privy) used a chamber pot and needed to empty it

into a cesspit.

Some cities had public latrines to keep the streets from being fi lled with

fi lth. London, in the 14th century, had a row of public toilets along the

river where the tide in the Thames Estuary would fl ush the cesspits out

twice a day. The privies were divided into men’s and women’s. River la-

trines gradually turned the city’s streams into open sewers.

In 1357, King Edward III set out to inspect the Thames and Fleet rivers.

These rivers stank badly even by medieval standards. Only 10 years earlier,

the Black Death plague had swept through London, and nobody knew

what had caused it, but “bad air” was considered a great risk factor for a

repeat of the plague. He closed some latrines along the Fleet and Thames

rivers and forbade the building of new ones. The rivers were dredged, and

owners of the latrines that remained had to contribute to the cost.

Garbage

Cities had the most diffi culty with sanitation. In cities, people, animals,

and businesses were packed into a small space, with no room for each fam-

ily or business to develop its own outhouse or latrine pit. Waste often went

into the streets. This included not only human waste and animal waste,

but also butchering waste (blood, entrails, and skin). Dogs, pigs, and rats

roamed the streets eating what they could. Large city streets, especially

in the 14th and 15th centuries, were sometimes paved and had gutters

and drains. A wide street with two gutters could count on rain washing

the streets at times. Cities like London also employed rakers to sweep the

streets and carts and boats to carry the refuse away. Cities also tried to ex-

terminate rats, although they were not aware of the rat’s role in spreading

disease.

Latrines and Garbage

442

Medieval people maintained a certain amount of recycling for pragmatic

and economic reasons. Some food waste could be turned into materials for

industry, like the bones and skin from butchering that went to make glue,

leather, and parchment. Butchers may have dumped blood and entrails,

but much of what could have been dumped was sold to pie makers or given

to charity, since the poor were always happy to eat any animal products.

Worn-out clothing could always be made into something else, and even-

tually it became either high-quality toilet tissue or rags sold to the paper

industry. Parchment and paper were rarely thrown away; they were re-

purposed by having something else written on the reverse or by being

scraped or erased for a second use. Broken glass was called cullet; it was

collected to be melted again by glassmakers. Candle ends, which could

be melted down, were treasured to the point that they were part of some

servants’ wages and benefi ts.

Still, garbage disposal, particularly of industrial waste such as the scrap-

ings and used chemicals from tanning, was a huge problem in cities. In

Paris, there were civil trials in which neighbors sued butchers, arguably the

messiest of the trades, for fouling the streets and stinking up the air. Butch-

ers were supposed to haul their waste outside the city, but many put it into

the street instead. The city fi nally forced many butchers to move outside

the walls and locate along the Bièvre River, where tanners and dyers were

also locating. The river soon became nearly clogged with sewage, which

then fl owed into the Seine and eventually out to the sea.

Italian towns passed stringent regulations for keeping the streets clean.

Dumping water from upper windows was against the law; backyard privies

had to be walled up and lined with stone so as to keep from leaking. Streets

had to be kept clean; even grape skins were to be swept up. Neighbors were

responsible for periodically washing the streets with river water. Dead ani-

mals had to be hauled outside the city, as did all other bone waste. All vio-

lators who were caught were immediately fi ned.

Toward the end of the Middle Ages, some cities had built drains and

sewers into their main streets. Citizens who lived along these roads some-

times piped their waste into the city’s main drain system. The hygiene-

conscious Italian cities encouraged and at times required this, since it kept

the alleys from becoming smelly marshes.

Ultimately, the waste all emptied into the nearest running water. Cit-

ies situated on rivers were easier to fl ush, but the resulting river pollution

could be extreme. Smaller channels could become hard to navigate due to

the volumes of fl oating waste, and even large rivers smelled bad. The water

was no longer safe to use, which was a problem since many people had tra-

ditionally used river water. The fi sh were polluted as well and could not

safely be eaten. Improperly treated waste could also contaminate wells, es-

Lead and Copper

443

pecially within a city. Cities tried to keep public water supplies clean, but it

was not possible to keep anything entirely clean.

See also: Cities, Monasteries, Water.

Further Reading

Dean, Trevor. The Towns of Italy in the Later Middle Ages. Manchester, UK: Man-

chester University Press, 2000.

Gies, Joseph, and Frances Gies. Life in a Medieval Castle. New York: Harper and

Row, 1974.

Gies, Joseph, and Frances Gies. Life in a Medieval City. New York: Harper and

Row, 1969.

Hanawalt, Barbara A. Growing Up in Medieval London: The Experience of Child-

hood in History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Magnusson, Roberta J. Water Technology in the Middle Ages. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Wright, Lawrence. Clean and Decent: The Fascinating History of the Bathroom and

the WC. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1967.

Lead and Copper

Medieval Europe used gold and silver for coins, iron for weapons and

some tools, and only a few other metals for all other purposes. Copper was

mined on Cyprus, in Germany, and in a few other places. Trace elements

of metals like arsenic and antimony were found in the impure copper ore,

and, for cheaper products, they were often left in to add bulk; the best cop-

per, used for casting fi ne bronze and brass, had to be refi ned. Tin and lead

were often found with silver and had long been mined in England, France,

and Germany. Metal was also recycled. The Romans had used lead for many

purposes, and the pipes, gutters, and tools they left around Europe were

melted and recast.

Copper alloys commonly were used to make many household objects,

especially for the kitchen. Bronze was an alloy of copper and tin, with very

little zinc. Brass, on the other hand, was made of copper and zinc, with

little to no tin. Gunmetal, also called latten, used copper, tin, and zinc to-

gether. Lead could be mixed into any of these, especially latten. Since me-

dieval craftsmen had no sense that lead was poisonous, they did not hesitate

to use lead in metal alloys for pitchers and other table utensils. Latten was

the cheapest metal and could be used for many small cast objects, especially

candlesticks. Pewter was an alloy of tin developed in the later Middle Ages.

A poorer sort of pewter, used for pots and candlesticks, was made with lead

and tin. Fine pewter was made of copper and tin, and it was considered

Lead and Copper

444

nearly as good as silver. It had a higher proportion of tin, as compared to

bronze, which was higher in copper.

Bronze items were cast using the lost-wax method. The desired shape was

carved in wax, which was then packed into clay. When molten bronze was

poured into the clay, the wax melted and poured out drainage holes. The

bronze fi lled the spaces and, when cooled, took on the original shape of the

wax. Bronze casters were sometimes called potters in English; casting mol-

ten metal is also called foundering, and the place that does it is a foundry.

Bronze casters made many kinds of kitchen pots, and they also made

chamber pots. Households used as many bronze pots as iron ones, although

later times used only iron skillets and cauldrons. Bronze casters also made

church bells, which was an art in itself. Those who specialized in the craft

were bell founders. The bronze for bells was approximately four-fi fths cop-

per and one-fi fth tin.

Bronze and brass were used to make funeral effi gies and memorials.

Only royalty could afford three-dimensional cast bronze effi gies. For one

set of effi gies of King Henry III and his daughter-in-law, Queen Eleanor

of Castile, a goldsmith carved the wax originals. A bronze founder used

these wax fi gures to mold and cast in bronze. Brass was a new material in

the Middle Ages. It was cast in sheets and made into fl at, etched funeral

memorials.

Thousands of pilgrims came to holy

places like Canterbury, the site of the

martyrdom of Saint Thomas. They

wanted to carry away a holy souvenir,

but many of them were humble people

who could not afford much. Lead

badges were the cheap solution. A lead

badge could be affi xed to the pilgrim’s

hat or pack, and it would not easily

break or rust. Lead pilgrim badges in

many shapes were turned out by the

thousands all over Europe. (Museum of

London/StockphotoPro)

Libraries

445

Lead was a very useful metal because it was soft and because its melt-

ing point was so low. It did not require specialized furnaces, but it kept its

shape in air temperatures. Plumbers melted new and old lead into sheets

and then cut it into roof tiles; lead roof tiles were the most popular kind.

Lead was also used to hold together panes of glass, both clear and stained.

Lead was easy to cast and bend, and it could be soldered in place with a

mixture of tin and lead, using salt or tallow as the fl ux.

Lead pipes formed the water systems of many monasteries and cities.

Rome had used lead for pipes, and no physicians had yet noticed lead poi-

soning, perhaps because it was widespread. First, the metal was melted and

cast in sheets. Long strips of sheet lead were bent around a wooden pole,

and then the pole was removed. The pipe needed a fi rm seam to make it

watertight. Lead was easy to melt, but it always needed a mold, even for a

seam. The new pipe was fi lled with sand and wrapped in clay, leaving only

the crack where the seam needed to be. Now the craftsman could pour

very hot lead into the crack, where it melted the edges of the pipe and then

cooled, forming a welded seam.

Both pewter and pure lead were molded to make decorative shapes and

pins, such as badges pilgrims pinned to their hats. Although lead was not a

precious metal, lead pilgrims’ badges could be mounted with small, inex-

pensive jewels. Lead could also form a white crusty oxide when exposed

to ammonia, and this white lead was the main source of white pigment in

paint. Roasted, it turned yellow and orange.

See also: Bells, Iron, Kitchen Utensils, Painting, Water.

Further Reading

Badham, Sally. Monumental Brasses. Botley, UK: Shire Publications, 2009.

Buckley, Allen. The Story of Mining in Cornwall. Fowey, UK: Cornwall Editions,

2007.

Egan, Geoff. The Medieval Household: Daily Living c. 1150–c. 1450. Woodbridge,

UK: Boydell Press, 2010.

Harvey, John. Mediaeval Craftsmen. New York: Drake Publishers, 1975.

Magnusson, Roberta J. Water Technology in the Middle Ages. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Spencer, Brian. Pilgrim Souvenirs and Secular Badges. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell

Press, 2010.

Libraries

In ancient times, there had been libraries of clay tablets and scrolls, and the

Romans had both public and private libraries in many cities. Some public

libraries in Rome were like modern reading rooms, and some were placed

Libraries

446

in the building that held the public baths. Each book, in the form of a

parchment roll, had a little tag on the end of it bearing the author’s name.

Rolls were stacked on shelves or set upright into buckets. Some of these

ancient Latin scrolls were still housed in the oldest medieval libraries, such

as in Rome itself. Another form of book, the codex, was developed in the

fi rst century

A.D . A codex was a stack of thin boards that were covered with

parchment; little holes were drilled in the edge so the boards could be

bound together with cord.

Christian writers in the early Middle Ages preferred the codex over the

scroll for their copies of the gospels. In many cities, bishops amassed private

libraries, usually consisting of either books of the Bible or commentaries

on the Bible and religious issues. However, some bishops also had secular

works in their libraries. In the seventh century, the famous scholar Isidore,

bishop of Seville, owned a notable library. He had not only religious and

biblical books but also copies of books by famous Latin writers of earlier

centuries, along with medical books and legal writings.

In the early 800s, Charlemagne made great efforts to broaden Frankish

book production. He set monks and scholars to copying books, and

he organized schools to encourage literacy; he and his sons attended,

to set the example. Under Charlemagne’s encouragement, monasteries ’

book holdings expanded. Libraries that contained only 30 or 40 books

before Charlemagne’s reign had as many as 300 books by the middle

of the ninth century. The largest monastic libraries had more than 600

books, an astounding achievement in the relatively primitive Frankish

kingdom.

The greatest libraries of medieval Europe were located in Cordoba, the

capital of Muslim Spain. Arab scholars were enthusiastic translators and

writers, and the city kept hundreds of copyists employed. The caliph’s li-

brary was reputed to have 400,000 volumes, and it was one of perhaps as

many as 70 other city libraries. Other Andalusian cities like Barcelona had

great libraries and became centers of learning that drew scholars from the

Christian countries. The Muslim passion for translation preserved, at least

in Arabic, many Greek classics that were otherwise lost. Aristotle’s reentry

into the scholasticism of Christian Europe began with the Arabic transla-

tions of his works, which then were translated into Latin for use in Euro-

pean universities.

As the monastic movement spread across Europe, monasteries devel-

oped libraries in conjunction with their scriptoria, especially in Italy, Ger-

many, Switzerland, and England. The scriptorium was a well-lighted room

where monks worked as scribes, making new copies of books and, like the

rest of the monks, working six days a week. Sunday was not a workday, and

in many monasteries the monks were to get a book from the monastery

library and spend the day reading the Bible or other Christian literature.

Libraries

447

Most monastery libraries had only a few hundred books, but they were

required to have at least one book per monk. Books from the library also

were used in the schools that many monasteries started, where the monks

taught the village boys to read.

A few monastery libraries loaned books to the public, but with a strong

emphasis on making sure the books were brought back. In some cases, the

borrower had to leave something of value with the librarian as a deposit to

assure return of the borrowed book. Some libraries coped with the problem

by chaining the most valuable books to desks. The problem of borrowers’

failure to return books, whether in public, private, or monastery librar-

ies, brought about the creation of many forms of the “book curse.” These

curses threatened the careless reader with dire consequences if he failed to

return the book, including eternal damnation, disease, agony, and the judg-

ment of God himself.

By the end of the 14th century, there were more than 75 universities

in Europe. Each one had its own library, often with a “great library”—a

reading room where people could study. The university’s “small library”

was a storeroom for books loaned to members of the university. Univer-

sity libraries developed specifi c book collections for the study of theology,

both church and civil law, medicine, and sciences such as geography and

Bologna’s university was the fi rst established in medieval Europe. Its library has one

of the greatest antiquarian book collections in the world. (Kelly Borsheim)

Lights

448

astronomy; these books were loaned to students. Residential colleges

within the universities, acting as dormitories, also collected libraries for

their students. Other sources of books for students were stationers’ shops—

the publishers of the day—where books were copied and bound and loaned

to students for a fee.

See also: Books, Monasteries, Parchment and Paper, Printing, Univer-

sities.

Further Reading

Butt, John J. Daily Life in the Age of Charlemagne. Westport CT: Greenwood

Press, 2002.

Casson, Lionel. Libraries in the Ancient World. New Haven, CT: Yale University,

2001.

Murray, Stuart A. P. The Library: An Illustrated History. New York: Skyhorse Pub-

lishing, 2009.

Lights

The primary source of light in the Middle Ages was the sun; nearly all work

was done during daylight hours. Workers began with the sun and stopped

work at sunset. Many guilds specifi ed that craftsmen could not work at

night, since the available light sources were so poor. It would be too easy

to miss fl aws in the work. Certain kinds of work required many windows,

and workrooms had as many windows as could be managed without los-

ing suffi cient heat. Many crafts worked in the open air.

The secondary source of light, indoors, was the fi re. Most houses had

open fi re pits or hearths in the center of the room. Since windows provided

light but also allowed heat to escape, houses in the northern regions had

few windows, and they were typically shuttered in the winter. House interi-

ors were dark, and the fi re provided the light for most inside activity. It was

enough for spinning, basic sewing, animal care, and basic cooking. When

fi replaces were invented for castles and began to be incorporated into some

newer city houses, fi res could be brighter without fi lling the room with

smoke, and they probably provided more light.

Fires could be started with a spark from fi re irons. The friction of the

irons being rubbed together cast sparks onto kindling materials. Light-

weight, dry materials like straw, tow, dried toadstools, and dried weeds

caught the spark. Dry twigs and good kindling wood made the fi re grow,

and fi nally solid wood could be piled onto it. Oak, ash, and beech were

the best woods for household fi res. Starting a fi re was such a production

that most households tried to keep their fi re from completely dying out.

Lights

449

Banking large coals of burning wood with ashes slowed the combustion

and meant that in the early morning, the servant or housewife who raked

through the ashes could fi nd coals that soon glowed red again. If the coals

did not light, neighbors were often willing to send a few good coals over

in a fi re pan. Another simple tool, the pottery couvre-feu, or curfew, was a

ventilated lid that could help bank the fi re for the night. With good kin-

dling, the fi re was soon hot again. Fires could be made hotter with a bel-

lows. Men also blew on fi res to make them hotter.

Fire could be a portable light when carried in an iron or pottery bas-

ket called a cresset. Lighthouse beacons were controlled fi res in cressets.

Watchmen in cities kept cressets with burning wood all night; they could

carry them to the scene of a disturbance.

The liturgical year included several festivals when candles and other

lights were featured. A medieval Latin hymn for Easter describes the

lighting of a new fi re with fi re irons and the variety of lights brought from

home to be kindled at the new fi re. Pottery oil lamps with wicks fl icker-

ing into light, pine torches spitting sparks into the air, and beeswax can-

dles, still smelling of honey and dripping wax onto the fl oor, are described

vividly.

Torches were the most ancient kind of light and were used less as the

Middle Ages passed. Their natural pitch content made the wood burn well

for a long time. They were used in outdoor processions at night and in

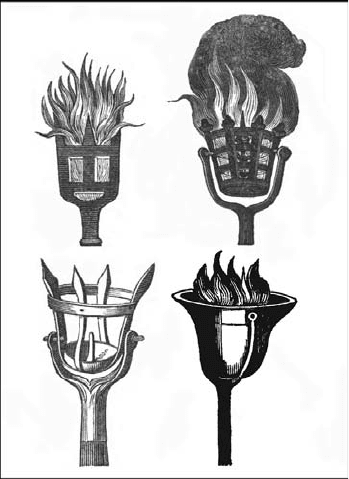

Cressets were small baskets to carry

coals and fi re. The cressets pictured

here could be carried like torches. They

were the only kind of light that could

be picked up easily and carried out-

doors to the scene of an emergency, so

night watchmen always had cressets and

a central fi re source. (Francis Douce,

Illustrations of Shakespeare, and of

Ancient Manners, 1807)