Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Machines

460

Another advance was the bowspring, which was fi rst used in its sim-

plest form—an overhead branch that wanted to spring back up when pulled

down. If a saw was attached to this simple spring, the job of lifting the saw

back up was much easier for the human operating it. Combined with a foot

treadle, the spring made sawing go much faster. A lathe operated at high

speeds if its spindle had a cord wrapped around it, attached to a foot treadle

below and a branch overhead. The operator had his hands free to cut and

shape and needed only his foot for power.

The last simple machine to be developed was the crank, which evolved

from the windlass. It seems simple and obvious in modern times, but the

crank was not invented until the 14th century, when it begins to show up

in pictures as part of a grindstone. The fi rst cranked grindstones had a crank

on both ends of their axles so that two people could make them spin as

fast as possible. A crank also helped wind a crossbow’s bolt back; turning

the crank many times required less strength than pulling the bolt back by

main force. The crank went on to become the simple machine for cranes

and wells.

In the 15th century, inventions began to use complicated cranks and

started to integrate them with other machine principles. The carpenter’s

brace, which uses a compound crank to power a hand drill, fi rst shows

up in records in Flanders around 1420. An Italian drawing of the 1450s

shows a waterwheel with two cranks and connecting rods operating a pump,

and we have the fi rst records of a paddle-wheel boat in the same period

in Italy. Connecting rods permitted one power source to turn fi ve paddle

wheels or three separate mechanisms. With this invention, machinery was

poised to move into the modern age.

When a fl ywheel was added to a crank, it smoothed and multiplied the

crank’s motion. Any dead spots in the process of turning the crank were

smoothed out by the inertia of the wheel. A grindstone with a fl ywheel kept

spinning if the operator’s arm got tired. During the 15th century, mills

began using a fl yball governor to regulate the speed of their waterwheels.

The governor was a small device with a ball on a chain; once put in motion,

it used inertia to keep spinning. The faster it spun, the higher the ball rose

in its orbit. A mechanism connected to the governor raised and lowered a

gate on the mill as the fl yball rose or lowered; when the millrace became

too strong and the milling equipment could be driven too fast, the fl yball

governor whirled its ball higher and triggered the mechanism to lower the

gate and cut the amount of water.

Theorists and inventors explored the means of powering movement.

They were fascinated with the idea of creating a machine that would power

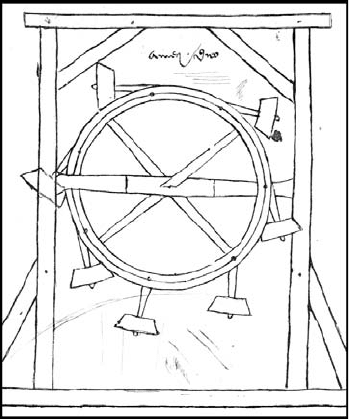

its own perpetual motion. Villard de Honnecourt, an outstanding engineer

of the 13th century, left behind notebooks that included his concept for

perpetual motion: a wheel with an odd number of free-swinging mallets,

Machines

461

each fi lled with mercury, fastened to its outer rim. As the mercury moved

inside the hollow mallet heads and the wheel turned, there would always be

enough force at the top of the wheel to make it turn and raise the mallets at

the bottom. The mercury-fi lled mallets would become their own waterfall,

powering the wheel. Other inventors suggested using magnets. The mod-

ern generator that creates an electrical fl ow by spinning magnets around a

coil of wire seems a direct descendant of these medieval brainstorms.

Another popular and fanciful use for machines came with the invention

of clockworks. Not content to ring a chime on the hour, a medieval clock

maker created a mechanical show of crowing roosters, spinning dancers, or

hammering workmen that came out and performed. Even before clocks

were invented, the gears and weights that drove them were being used in

other gadgets. There were “automata,” toys for the rich, such as a bird

that appeared to drink from a cup. Villard de Honnecourt explained how

to use a gyroscope to suspend coals inside a ball, thus keeping one’s hands

warm without allowing the coals to touch the sides of the ball and burn

the holder.

One toy was an early experiment with the power of steam. The experi-

menter had a pottery jar with only a small hole near the top, corked. Heat-

ing water to boiling, he allowed pressure to build up until the cork popped

out and steam came out in a stream. The jug could be made in an amusing

shape—such as a man appearing to spit the steam—to entertain guests. An-

other more useful gadget experimented with the power of rising hot air by

operating a fan inside a chimney, powering a meat-roasting spit or vents to

regulate the fi re’s heat. This rare gadget appeared only at the close of the

Villard de Honnecourt hoped that

moving mercury inside each hammer’s

hollow head would provide enough

force to keep the wheel turning

indefi nitely. As far as we know, he never

built a model to try the idea. (Jean-

Antoine-Baptiste Lassus, Album de

Villard de Honnecourt, 1858)

Magic

462

period, and only in cities, but it was a step forward that was utilized by the

next industrial revolution.

See also: Clocks, Mills, Tools, Weapons.

Further Reading

Bowie, Theodore, ed. The Medieval Sketchbook of Villard de Honnecourt. Mineola,

NY: Dover Publications, 2001.

Gies, Frances, and Joseph Gies. Cathedral, Forge, and Waterwheel: Technology and

Invention in the Middle Ages. New York: Harper Collins, 1994.

Gimpel, Jean. The Medieval Machine: The Industrial Revolution of the Middle Ages.

New York: Penguin Books, 1977.

White, Lynn, Jr. Medieval Technology and Social Change. Oxford: Clarendon Press,

1962.

Magic

The word magic means “of the Magi.” The Magi were the wise men of Per-

sia, the Zoroastrians. In the Bible story of Jesus’s birth, some Magi came to

see the baby, having read in the stars that a great birth had just taken place.

In medieval times, this ability to read the stars and know charms and spells

was originally associated with the Zoroastrians and wise men of the East, so

it was called magic.

Although the popular idea of the Middle Ages is that witches and witch

hunts were common, the heyday of interest in witches came in the 16th and

17th centuries, not during the medieval period. The church and the civil

authorities outlawed and prosecuted the practice of magic, but there were

few trials, and they were confi ned mostly to the period of the Cathar Inqui-

sition. Most common superstition and magic went on as part of daily life.

Sleight of hand, the form of magic the modern world enjoys as enter-

tainment, also was practiced as entertainment in the 14th and 15th centu-

ries. Some were so simple that a modern watcher would quickly suspect the

trick, such as using a very fi ne hair to pull on an object to make it move or

suspend it in midair. Some entertainers played shell games—making a ball

vanish under a set of cups—or could get free from a rope with a concealed

knife. Entertainment magic at royal courts could also involve mechanical

toys. If the creator would not explain or show the mechanism, then the

court could be astonished at the action of the automaton. Any self-pro-

pelled vehicle was a cause for wonder. One engineering trick made a toy

bird appear to drink wine.

Real magic in the Middle Ages came in two forms, although it was not

always easy to tell them apart. Natural magic was just a part of nature; most

natural magic has been defi ned by modern science as natural processes,

while other beliefs were harmless superstitions. The other kind of magic

Magic

463

was occult, demonic magic that called on spirits. It was not accepted by

most of society, and certainly not by the church.

Natural Magic

Natural magic was diffi cult to understand and defi ne. Since all healing

was miraculous in some sense, then all medicines had magical properties.

The antibacterial properties of garlic have now been verifi ed and measured,

but to a medieval healer, garlic simply had a natural power of magic over

some hurts and illnesses. The lodestone ( compass ) had a magical property

of always pointing north, and magnetized stones magically drew together.

Some natural magic was imaginary but was considered real at the time.

For example, astrology explained that the stars gave certain plants or min-

erals powers to cure or protect. No less an authority than Thomas Aqui-

nas believed that the stars worked infl uences on things on earth, causing

magnetism, the medicinal properties of herbs, and the growth and death

of all life forms. When so many things were unexplored and unknown, the

world was full of magic. The real and the imaginary were not well distin-

guished.

Normal medical practice involved natural magic: a medicinal herb could

have more strength if it was picked at dawn or at midnight. Its magic was

increased by using it in combination with other herbs or substances or by

preparing it with certain rituals. If a plant looked like a snake, its sap would

help with snakebite—that was natural magic. The principles of natural

magic were sympathy and antipathy. Sympathy meant that things worked

on or cured what they resembled or had some affi nity for. Antipathy was

the opposite; if two animals were antagonists in the natural world, then a

remedy from one could help cure wounds caused by the other.

Similar to natural magic was the magic of faith. It was ordinary medi-

cal practice to appeal to the proper saints to help with a problem. Saying

certain prayers a number of times could also help the sick, since Jesus had

promised to answer prayers requested in his name. If a saint or God himself

accomplished a miraculous healing, rescue, or divine punishment, it was

not considered magic.

Traditional medicine, as refl ected in the Anglo-Saxon works “Lacnunga”

and the “Leechbook of Bald,” combined the natural magic of herbal lore

with more explicit magic. The use of a salve based on goosefat and herbs

accompanied other rituals. The user might have to act out a ritual at dawn

or at midnight, at a crossroads or under a full moon. The magic ritual usu-

ally included an incantation in which the disease was commanded to leave.

Bible terms were invoked, but not as ordinary prayers: for example, a medi-

cine was to be stirred with a stick on which “Matthew, Mark, Luke, and

John” had been carved.

Magic

464

Natural magic blurred quickly into a more explicit magic that was in a

gray area between what the church encouraged and what it condemned.

Some felt that superstitious rituals and taboos merely drew on the princi-

ples of the stars and the world, while others felt that they amounted to call-

ing on spirits and invoking supernatural power in unorthodox ways.

There are four basic principles of magic in these traditional medical

rituals. While any doctor of the time could prepare an herbal medicine or

salve, the magical method would require him or her to observe certain

taboos in the preparation: speak these words, remain silent, go barefoot,

don’t use iron, or don’t have sex for a day in advance. To a nonmagical

mind, these taboos and rituals have no connection to the effectiveness of

the ingredients. Another principle was to select ingredients not on the

basis of their components, but on the basis of some physical trait, such

as resemblance to the disease. Jaundice, which made the skin yellow, was

treated with something yellow. Male animals were considered stronger, so

the hair, bone, or fl esh of a male animal was supposed to make a stronger

medicine.

Astrology and incantations were the two other markers of magic. A rem-

edy’s strength was thought to depend on qualities the stars projected into

it; certain remedies needed to be tried under certain astrological signs. The

rays of the sun would add or subtract power from the herbs or other ingre-

dients of a medicine.

In the old Germanic tribes, written letters were considered magical; cut-

ting runes into a rock or a piece of wood not only conveyed information,

but it also worked magic. Runes could cure or kill, depending on the skill

of the one using them. Medieval occult magic continued to put emphasis

on the written word. Incantations had to be spoken over the preparation

or use of medicine; they could also be the medicine: for example, write the

names of the saints on a paper, and tie it to the sick person, or speak a word

like abracadabra over the remedy while preparing it. There were many

variants on Latin and other languages that created magical phrases to add

power to a medicine or salve.

Charms were special incantations to speak over ailments, usually phrases

with reference to the Christian religion. They were often very short stories

about angels or Christ healing a person of a particular problem, such as

toothache or headache. Repeating the story in its exact words was supposed

to cure the problem. While most charms called on the powers of Jesus and

the saints, some charms called on spirits to control the weather or give su-

pernatural power in some other way.

Amulets were objects carried to give magical protection against certain

problems. A hare’s foot was a common amulet that protected its wearer

from danger. Rosemary could keep away venomous snakes and evil spirits.

Mistletoe could ward away conviction in a court of law. Some amulets had

Magic

465

to be created with charms and other magical powers, such as herbs col-

lected under a certain astrological sign while reciting a prayer.

In aristocratic circles, some believed gems had magical powers of protec-

tion. A sapphire could cure eye disease; Saint Edward the Confessor’s ring

could cure epilepsy. Gem dealers encouraged these legends as a way to sell

gems. Books called lapidaries explained the magical power of gemstones.

The bishop of Rennes’ popular lapidary claimed that the magic of gem-

stones was merely the natural magic God had created in gems. Sapphires

could dispel envy, and magnets could detect marital unfaithfulness.

Relics could operate as amulets; dust from a saint’s tomb, or the host it-

self (surreptitiously taken home from Mass), could be carried as a protector.

Relics differed from true amulets in that the owner believed the power was

not in the relic, but in the prayers of the saint in heaven, but the dividing

line between a relic and a hare’s foot was not always clear to the common

people. The church viewed the misuse of relics as superstition, not as true

magic, and tried to teach the people not to use them this way.

Talismans were similar to amulets, but they had written words. A talis-

man’s words might be a prayer or the names of a saint, but often it was a

set of nonsense words or a pattern. One common pattern was to form the

opening words of the Lord’s Prayer, Paternoster, into vertical and horizon-

tal lines that crossed at the central N . Another was to form a magic square

This amulet from pre-Christian Iceland

is in the shape of Thor’s hammer. At

the top, a dragon’s head provides extra

magic for the amulet’s owner. Amulets

like this one were used well into

Christian times, but Christians also

made their own charms based on the

saints. (Werner Forman Archive/

StockphotoPro)

Magic

466

in which the same words read at the top and bottom and vertically: sator,

arepo, tenet, opera, and rotas formed a square like this. Tenet is a Latin word,

as is opera, but they had no meaning in the square. The power of the letters

was not in their meaning or in invoking any saint.

Exorcisms were rituals to drive out demons that were causing illness.

They could be carried out by priests under rituals prescribed by the church,

but they were done more often as folk remedies. The ritual typically con-

sisted of a text for the exorcist to read while making the sign of the cross

at many points and “abjuring” demons and elves to leave the person alone.

Names of saints were invoked, but mysterious foreign names were also in-

voked, with incantations of Latin and other foreign words.

Astrology and Alchemy

Astrology and alchemy were magical sciences. They were connected to

astronomy and chemistry, but they sought to use the power of the stars and

minerals to gain power. They were not illegal, and some monarchs made

use of both magical sciences.

Astrology, the magical science of the stars, came to Europe through Ar-

abic books of lore. It appeared to be very scientifi c, and medical schools

began to incorporate its teachings. Astrology was a part of natural magic,

rather than occult magic; the stars had certain powers, and these powers

were morally neutral. It was a matter of scientifi c study to learn what the

stars were infl uencing or predicting. Many European kings, including

the scientifi c emperor Frederick II, had astrologers to tell them when

they should do various things.

Arabic texts on astrology also suggested ways to incorporate the stars

into magic rituals. These rituals incorporated many of the common tradi-

tions (written names, herbs, and charms) but included references to the

constellations and used astrology to recommend when to use the rituals.

Some charms went farther and instructed the user how to pray to the stars

or planets.

Alchemy was a form of natural magic that evolved into the true sci-

ence of chemistry. In early forms, alchemy invoked stars and spirits or used

charms and amulets. While the goal of the alchemist was to produce gold,

the actual practice of alchemy involved many practical techniques still used

in chemistry. Alchemists distilled, melted, classifi ed, and observed. Their

laboratory equipment began as the apparatus of natural magic but became

the tools of science.

The magical side of alchemy often depended on the supposed secret

writings of the ancients. Aristotle had written a secret treatise and had taken

it into the grave; the priests of Egypt had preserved ancient knowledge.

One book, supposedly by Aristotle, was widely read, but the text frequently

Magic

467

mentioned how it must be kept secret. Legends grew up around other fi g-

ures, such as Pope Sylvester, who had begun life as a humble scholar in

Muslim Spain, the scientist-cleric Roger Bacon, and the monastic author

Albertus Magnus. The stories told about how they had obtained secret

knowledge with magic. In some stories, they discovered hidden treasure,

and in others, they made heads that could talk. There were stories that

these men had written secret books about their lore—the original wizards’

books.

Occult Magic

Occult magic was an appeal to the spirits to achieve what Christians con-

sidered it was only proper for God’s power to do. It often had its roots in

pre-Christian pagan religion. Just as Christians had prayer rituals to invoke

the help of the saints, pagans had used rituals to invoke the help of their

gods and spirits. However, some medieval occult magical practices are not

directly connected to pagan religion as we know it.

The chief aims of occult magical practices were usually love charms,

charms to become pregnant, or charms to infl ict death on an adult or un-

born baby. While there are records of both men and women using charms

Medieval alchemists were unscientifi c scientists, but some of their discoveries led to

the development of chemistry. They combined elements and other minerals, but with

only magical theories of why materials reacted with each other. The alchemist’s tools

resembled those of a modern laboratory. (Paul Lacroix, Moeurs, Usage et Costumes au

Moyen Age et a l’Epoque de la Renaissance, 1878)

Magic

468

and potions, women had a greater reputation for this knowledge. Younger

women tended to go to old midwives to ask for a love potion or a charm

for or against becoming pregnant. Many midwives were practical physicians

who delivered babies and did not dabble in charms, but some did.

Since the early Middle Ages, European rulers had tried to outlaw occult

magic. Since they themselves believed in natural magic, they did not try to

outlaw the simple use of folk remedies and charms. They did try to regu-

late charlatans who traveled about performing exorcisms or curses. Char-

lemagne decreed that those found guilty of sorcery should become slaves

on church estates and that those who sacrifi ced to the devil should be ex-

ecuted. Other kings extended these prohibitions to charms and potions,

probably because they believed in their power and considered them to be

no different from hurting someone with a weapon.

The church listed sins of magic in its manuals for penance, and both

theologians and preachers spoke strongly against magic. Franciscan and Do-

minican friars, who preached to the common people in the 13th century, spoke

against magic frequently. Bernardino of Siena, in the early 15th century, col-

lected objects from magical rites and burned them publicly. Theologians

tried to defi ne the line between natural magic and occult magic. A magnet

was considered natural magic, so the church acknowledged some forms of

magic; Thomas Aquinas attributed the magnet’s powers to the stars. But

other forms of magic could not be natural and must be occult, and there-

fore illegal. The church also condemned magical use of herbs or even holy

relics in ways that seemed superstitious rather than properly faithful.

During the Inquisition in Toulouse, which sought to end the Cathar re-

ligion, the inquisitors also asked about magic. Some people accused others

of witchcraft. The accused confessed, often under torture, that they had

used wax images to infl ict pain and death, had carried out rituals to dedicate

themselves to the devil, and had made charms and potions to harm others.

The inquisitors recorded their testimony and permitted them to repent

of these things as sins, but the civil authorities tried them as witches, and

most were executed.

Most other trials of witches during the Middle Ages involved high-

profi le cases. When the Frankish emperor Arnulf died suddenly in 899,

probably of a stroke, some people were accused of bewitching him. King

Lothar II claimed that his lack of children was caused by witchcraft and

sought to divorce and remarry on those grounds. The Knights Templars

were accused of practicing magic against the king of France and the Pope,

and Joan of Arc was convicted of witchcraft by the English. When people

were offi cially condemned for witchcraft, they were burned alive.

However, for much of the period, there was a legal deterrent against

bringing accusations of sorcery and witchcraft. The accuser was expected

to prove his allegations, and if he could not, he could suffer the penalty

Magic

469

the defendant would have faced. This made trials for sorcery rare, but in

towns and villages, when someone was suspected of casting hostile spells

and charms on others, the people often took informal action and killed the

witch by drowning, burning, or other means.

True occult magic took the principles of common magic and went fur-

ther. Magicians used rituals and taboos, resemblances, and incantations but

with more elaborate, secret, and usually violent alterations. Spirits other than

saints and angels were invoked, and the purpose was often to do harm: to

kill, to curse, or to make someone do something against their will. Charms

were curses when they were intended to bring trouble on someone. The

natural magic of similarity, or sympathy, was often invoked. An object that

resembled someone, either naturally or perhaps by being shaped to resem-

ble him, could be used to gain power over him. A knife stuck in a dairy

barn wall resembled a cow’s teat and could be used to steal milk or curse

the cow. A wax fi gure of a person could serve as a proxy for infl icting pain

on the person.

Divination was the practice of telling the future, usually from signs in

nature but sometimes from man-made objects like dice. Diviners claimed

to interpret thunder or bird calls. Thunder had different meanings in each

month, particularly in months when thunder was rare, and it could proph-

esy anything from good harvest and peace to death for certain people and

war. Diviners could look for portents in a refl ecting basin or even in holy oil

put onto a fi ngernail. There were also many superstitions about lucky and

unlucky days or events. “Egyptian days” were always unlucky, and nobody

should get married or undertake anything important on them. Divination

could uncover unknown information, such as the identity of a thief or the

location of lost property.

The darkest side of medieval magic was the necromancy that took place

among some priests, monks, and others who were ordained for a church

role, including many university students. They could read, and they had

access to many books others did not know. They knew the rituals, and they

were able to concoct corrupt versions. Most priests and monks remained

wholly orthodox, but a small minority began to dabble in black magic.

Necromancy was different from superstitious common magic in that it in-

tentionally called on the devil and demons.

The most common kind of necromancy was a perversion of the rites

of exorcism so that instead of chasing away demons, the ritual invoked

their power. Much of what we know of these unusual medieval rites comes

from inquisitors of the 14th and 15th centuries. The inquisitors burned

the books they found, but they wrote an account of the contents, and they

also heard confessions of repentant necromancers. While some of the rites

they wrote about invoked demons’ names or used magical actions similar to

medical magic, other rites explicitly worshiped demons by making images