Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Mills

490

used for things other than grinding grain until medieval Europeans began

experimenting. In medieval Europe, wind and water powered an industrial

revolution. By the end of this era, harnessed natural power had been ap-

plied to nearly every manufacturing process.

The mill was a central part of every community. Every grain-growing

place (nearly all of Europe) required a mill nearby where farmers, usually

peasants, could bring their grain. Millers rarely owned the land they built

on; they paid rent to the landowner in fl our, cash, or eels from their mill-

ponds. Their income was taken straight from the grain brought to them.

They kept a portion and sold it for profi t. Since peasants could not watch

or control the milling process, they were dependent on the miller’s hon-

esty. Many medieval stories, including Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, depict

millers as cheats. It seems likely that most peasants believed the miller had

kept more fl our than he was due much as modern people often believe car

salesmen have cheated them.

Water Mills

In Roman times, waterpower was limited to grinding grain. Romans

had slaves for other work and did not look for mechanical substitutes.

In early medieval Italy, mills at fi rst remained tied only to grinding grain,

though, in the later Middle Ages, northern Italy became heavily developed

with other industries. In Muslim Spain, waterwheels did not develop be-

yond the primitive level. Water mills ground fl our and lifted water into ir-

rigation channels but were never exploited for other industrial uses. For

water to become a real industrial force, rivers had to be plentiful and swift.

Northern Europe had much more favorable rivers for water mills. Mills

were well established in Frankish lands by the time of Charlemagne, whose

laws protected mills. They also were used in Anglo-Saxon England. These

early mills could have been horizontal-wheel mills, copied from the Roman

ones. Archeological evidence suggests that the horizontal wheels were

closer in size to a large cartwheel than to a 19th-century waterwheel and

that they were fed water directly by a wooden pipe leading from a millpond

at a higher elevation.

Small horizontal-wheel mills operated at the margins of Europe

throughout the Middle Ages. These primitive mills are usually built over

a small stream, and a shaft sticks below the building into the water, where

a small turbine is mounted. Primitive mills like this, found in Scotland,

Norway, Romania, and parts of Bohemia, may have been maintained by

the community. Each user ground his own fl our; there was no professional

miller.

In France and England, though, the mills were larger operations and re-

quired professional millers. These millers paid rent to the landowners, often

Mills

491

in the form of fl our and eels. The standard arrangement for the miller was

to grind a farmer’s grain and keep a portion of the product. He could sell

it or use it for his rent. Manors had their own mills, too, where the lord’s

own grain was processed. Monasteries often built mills.

During the 13th century, mills in Northern Europe changed to using

vertical wheels. Vertical wheel development added much more power to

waterwheels. The medieval water mill could grind far faster and more effi -

ciently than the horizontal-wheel mill. They were then adapted into com-

plex power trains that could run many other machines.

Vertical wheels had many slats, or buckets, for the stream to push against.

The fi rst wheels were designed as undershot wheels; the stream passed

under them, pushing the slats forward and up. Later medieval mills used

overshot wheels, but these required a natural waterfall or signifi cant engi-

neering to create a source of falling water. Only overshot vertical wheels

could produce enough power for the many industrial uses that water mills

were soon applied to.

The power train depended on wooden gears, chiefl y to turn horizontal

power into vertical power. Simple medieval gears were wheels with wooden

or metal teeth; wooden gears made with wheels and pegs were the most

common, although they broke easily. Using the heaviest gears to transfer

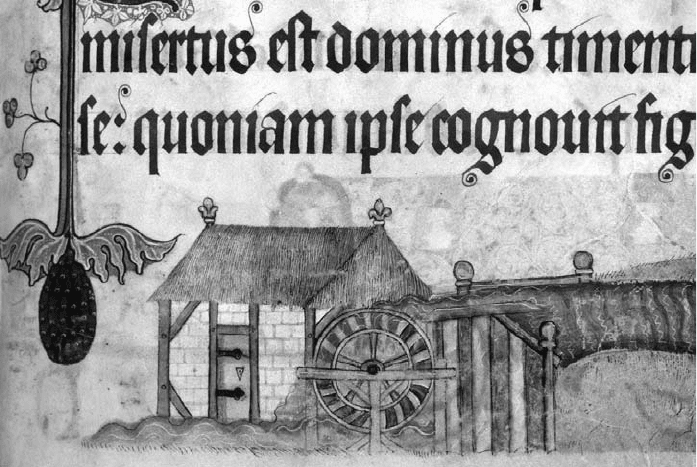

The Luttrell Psalter appears to show an overshot, vertical waterwheel on a small rural

mill. A country mill like this was probably used for grinding fl our, but mills in larger

towns were built to serve many other crafts. (HIP/Art Resource, NY)

Mills

492

power from the waterwheel to a drive shaft, power trains could add more

gears along the way to drive additional machines.

Waterwheels drove hammers that beat on cloth for fulling or crushed

metal ore, olives, paint pigments, linen rags for paper pulp, or grain mash

for beer. Armor makers used waterwheels to run polishing wheels, and

carpenters used them for wood saws. Blacksmiths built larger ironworks

because waterpower could drive large bellows tirelessly, and this increased

fi repower heated the iron to the higher temperatures needed for steel and

pig iron.

Cistercian monasteries always included a stream diverted through the

main building, fi rst to turn waterwheels to power the monastery’s work,

and then to fl ow through latrines on its way out. Some Cistercians used

waterpower to crush olives or maintain iron forges. The main monastery

at Clairvaux, in France, ground and sieved wheat fl our, tanned leather, and

fulled cloth.

By the late Middle Ages, there were so many water mills operating in

France and England that they blocked travel on the rivers. Mill operators

built dams and dug channels to alter the river’s fl ow for their advantage,

which often affected the conditions for mills downstream. There were bit-

ter lawsuits over new mills when they cut waterpower for other mills. Kings

tried to license mills to regulate them.

Towns dealt with the high need for mills by digging millrace channels at

river bends. They diverted some of the water from its natural course, forc-

ing it through narrow, straight channels with strategically placed water-

falls. A town with the right site could operate 10 or 12 mills within a short

stretch, enabling the craftsmen to power a number of businesses.

Some water mills were located under town bridges, while others fl oated

and were tethered mid-stream. There is 12th-century evidence for fl oat-

ing mills on the Seine near Paris and in Venice. There were a few mills that

operated with the power of rising and falling tides, but they were not as

successful. Waterwheels were not useful in coastal, fl at regions where the

streams were too slow. Tidal mills could not provide the same power as

river-powered mills, but they occurred throughout the later Middle Ages

along the coasts of Italy, France, England, and the Low Counties.

Windmills

Windmills appear to be a European invention. Although many medieval

inventions originated in China or India, wind technology remained primi-

tive in China. Coastal Europeans, who had strong sea breezes but few fast

streams, developed windmills as an alternative source of harnessed power.

Windmills show up in written records around 1180 in England and Nor-

mandy. The technology appears to have spread quickly; during the Third

Mills

493

Crusade (1190–1192), engineers in the Crusader army built the fi rst wind-

mill in Syria.

By 1200, windmills had spread to most parts of Europe. Flanders (mod-

ern Netherlands) invested heavily in windmills. Its steady sea breeze was

put to work pumping water out of the low-lying land. Windmills pow-

ered wheels with buckets that scooped water up and poured it into canals

or troughs. Other windmills ground fl our and worked other kinds of ma-

chinery. The largest number ground wheat and other grains using a pair of

heavy horizontal millstones.

Medieval windmills were post mills. The windmill was built around a

post that supported the building and allowed it to turn so it could catch

the wind from any direction. The mill’s central post was supported by four

or six cross-trees, large oak legs resting on stone blocks. The central post

rose up into the building, and it held a large wheel with a bearing. This

supported the mill’s fl oor, which was raised above the ground. Sometimes

the cross-trees and post were visible, but often the miller built a housing

around them to protect them from the weather. Medieval illustrations show

both kinds of design; without a housing, the mill seems to stand on chicken

legs, while with it, it looks like a tower that stands on the ground.

Inside the mill, the main fl oor was supported by beams that turned

around the central post, with an upper fl oor reached by a ladder. The gears

and beams were all made of wood, though some edges and joints were rein-

forced with iron. Millers kept things running smoothly by oiling them with

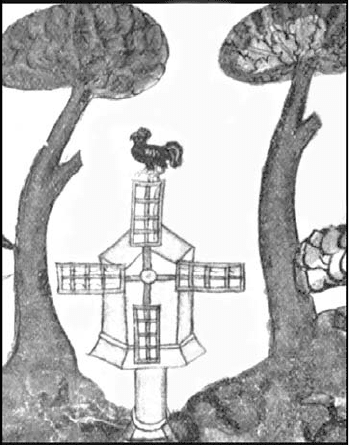

The original windmill of the Middle

Ages turned on a post so that it could

catch the wind as its direction shifted.

The four large sails were wooden

frames covered with tightly stretched

canvas, like ship’s sails. In this picture

from an illuminated manuscript, the

miller has placed a weather vane on

top of the building. As the wind

shifted, he turned the heavy mill by

hand, perhaps with the help of an ox

or donkey, until the sails had full

power. (Richard Bennet, History of

Corn Milling, 1899)

Minstrels and Troubadours

494

tallow. The machinery was attached to the axle of the sails, which came into

the upper fl oor. The standard post mill had four large sails. Each sail was

made of a wooden frame with canvas stretched across it.

The mill had to be turned on the post so that its sails faced into the

wind most effi ciently. The mill had a long beam that was used as a tiller to

turn it. The beam often had a wheel at the end so it could roll in a circle

around the mill, and sometimes it could be hitched to an animal. By the

late Middle Ages, some mills had a smaller set of sails mounted on the tiller

beam. When the main sails were pointed into the wind, the tiller’s fantail

was protected from the wind and did not move. When the wind direction

changed, the small sails drove the tiller forward, turning the mill into the

wind again.

Although most medieval windmills were rotating post mills, later ones

had a stationary building. By the 14th century, some mills were built of

stone and could house heavier equipment. The sails still needed to be

turned to face the wind, but the mill had been redesigned so that only a cap

on top needed to turn. The cap was made of wood, and it carried the sails

as it moved on a track.

See also: Iron, Machines, Water.

Further Reading

Gies, Frances, and Joseph Gies. Cathedral, Forge, and Waterwheel: Technology and

Invention in the Middle Ages. New York: Harper Collins, 1994 .

Hills, Richard Leslie. Power from Wind: A History of Windmill Technology. Cam-

bridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Holt, Richard. The Mills of Medieval England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing,

1988.

Langdon, John. Mills in the Medieval Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

2004.

Lucas, Adam. Wind, Water, and Work: Ancient and Medieval Milling Technology.

Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers, 2005.

Squatriti, Paolo. Water and Society in Early Medieval Italy, AD 400 –1000. Cam-

bridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Minstrels and Troubadours

The entertainers we know as minstrels went by many other names during

the Middle Ages. They were ioculatores in Latin, players and entertain-

ers, and gleemen in Anglo-Saxon England. Their most common name in

medieval French was jongleurs, which became the modern word jugglers .

Jongleurs could often juggle, but they did much more. They were the all-

purpose professional musicians, actors, and players of the time and could be

found at fairs, in castles, and in city squares.

Minstrels and Troubadours

495

Troubadours, the courtly poets who sang in 12th- and 13th-century

Provence, were of a higher class. Most were nobility, and some were noble

ladies. Trobar meant “poem” in the language of Provence. Trobadors con-

sidered themselves poets set to music; they created the fi rst important po-

etry in vernacular speech, rather than Latin. By romanticizing the concept

of love, they permanently changed Europe’s view of women.

Minstrels and Jongleurs

A minstrel in Beowulf makes a stately appearance, singing heroic songs

for the king and his men. He was a scop (pronounced “shop”), a composer

of verse, not just a singer. He accompanied himself on a harp. Scops were

honored and seem to have lived at royal halls, though some may have trav-

eled. Traveling singers were known as gleemen and could have learned the

songs and stories the scops wrote.

In Charlemagne’s time, both in England and in the land of the Franks,

there were not only court poets and wandering singers. There were also

many other entertainers. They sang and danced, juggled and tumbled, put

on plays, and traveled with trained animals. The ioculatores —players—were

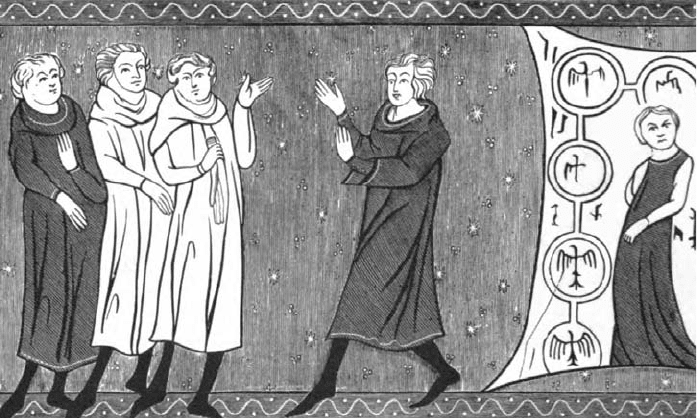

Jongleurs and minstrels were never considered respectable, even in medieval times.

They did not mind their own business, like most farmers or craftsmen, but traveled

from town to town, performing in the squares. Most of them were relatively poor;

they spent much of their time outdoors. The jongleurs in this French picture are

standing in the city square. They may be acting out a drama, or they may be telling

stories. (Paul Lacroix, Moeurs, Usage et Costumes au Moyen Age et a l’Epoque de la

Renaissance, 1878)

Minstrels and Troubadours

496

part of a tradition of singers, dancers, and clowns that stretched into Roman

times.

There were essentially three categories of minstrels, although the divid-

ing lines are fuzzy. Musicians sang and played many different instruments,

and, although they were ranked below the noble troubadours, they were at

the top of the general minstrelsy scale. Next were the jongleurs and mimes,

who could do nearly anything else. They did literal tumbling, acrobatics

such as headstands and handsprings. Some had puppet shows; others wore

costumes and acted like animals. Some had trained animals; others had

learned magic tricks while in the Middle East on Crusade. These perform-

ers could travel widely, since their acts did not depend on a common lan-

guage. A third group, the smallest, was made up of dropout scholars. They

traveled with minstrels and used their learning to entertain. They were sat-

irists and may have performed essentially stand-up comedy. They may also

have been the origin of court jesters.

There is not a large body of evidence for medieval jesters as a separate

profession from minstrels. Some halls may have employed midgets or sim-

pletons as fools, but, for the most part, minstrels did all the things that

popular belief attributes to jesters. They sang and joked, and they traveled

with their patrons. The offi cial court jester with a fl oppy, belled hat belongs

more to the Renaissance.

During Lent, all performances stopped. Some minstrels traveled to the

minstrel schools in France, where they exchanged stories and songs. Royal

minstrels received licenses to travel. Travel was very important for min-

strels, since they had to provide not only the old favorite songs and acts

but also new, fresh material. The minstrel school in Paris was the central

place to learn new songs, but any foreign travel, even to another region of

the same country, brought the minstrel into contact with different songs,

stories, and tricks. Minstrels taught each other to play new musical instru-

ments, and they traded the ideas for accompaniment and dance tunes.

Minstrels of all kinds used musical instruments to accompany themselves

or others. We have some written records of their music, but music notation

at that time did not record the rhythm, only the rising and falling pitches.

It is hard to reconstruct what the music actually sounded like. The instru-

ments were chiefl y stringed: harp, lute, and various forerunners of the vio-

lin. The lute was plucked (often with a quill), while the vielle was usually

played with a bow. The harp became the most common accompaniment

instrument, and in the modern imagination it is virtually synonymous with

minstrels.

Their music ranged from dance tunes, to bawdy tavern songs, to refi ned

epics about the lives of the saints. They could also mock or parody impor-

tant people to please the crowds; alternately, they could fl atter great men to

receive more pay. The music was not usually complex. It was restricted to

Minstrels and Troubadours

497

refrains that could be more musical between sections that were recited as

stories. The music also provided sound effects to go with the story.

Heroic stories, called romans or romances, were among the most popu-

lar. Some of the legends of Europe had their start in minstrels’ songs; the

singers developed new stories about well-known heroes, and in that way the

legends grew. The three traditional topics were called “Matter of France,”

“Matter of Rome,” and “Matter of Britain.” Matter of France meant the

deeds of Charlemagne and his knights, including the “ Song of Roland. ”

Matter of Rome meant stories about the ancient heroes, such as Aeneas.

Matter of Britain meant the legends of King Arthur and his knights. It

also included other early British legendary kings, such as King Lear of later

Shakespearean fame.

A low form of romance was the popular ballad, a rhymed story in the

common language. Robin Hood ’s legends grew out of the ballads sung

about him and other outlaws. Other stories, contes, told of lesser-known he-

roes, knights, kings, and saints. The typical 14th-century story of “Aucas-

sin et Nicolete” told about two teenagers in love, and it alternated singing

and telling. The heroes of these contes faced troubles, wandered into far-

off lands, and found true love. Minstrels also sang lais, which were shorter

lyrical songs. Fables, or fabliaux, told about human weaknesses and were

often vulgar like some of the stories in the Canterbury Tales.

Their dress at fi rst was not different from the clothing of those around

them, but as their profession became more established, minstrels and trou-

badours developed fancier costumes that made them stand out. They wore

brighter colors than other people, and typically they had short hair and no

beards. The distinctive jester hat developed only at the close of the Mid-

dle Ages at fi rst more as part of a holiday tradition than as part of every-

day minstrelsy. This hat often had donkey ears, an exaggerated crest like

a rooster’s, or large droopy points. It was made in garish colors. During

medieval times, though, minstrels wore hoods like anyone else, if perhaps

louder and more attention grabbing.

Using stage names or chosen names descriptive of their skills, minstrels

performed at weddings and many other feasts. At royal weddings, there

were hundreds of them. They performed in castles and great halls, as well

as at public marketplaces and fairs. Some minstrels were attached to the ser-

vice of a lord, at least for a time, and traveled with him when he attended

a feast. At the feast, they entertained in public and were paid by the host.

Good minstrels were paid very well by the nobility, and some aristocrats

who grew addicted to entertainment impoverished themselves.

The most skilled minstrels were permanent employees of great house-

holds. The records of Richard I of England show that he kept some favor-

ite minstrels for many years. They accompanied him to war. Later medieval

kings kept large groups of minstrels who could form a small orchestra and

Minstrels and Troubadours

498

put on plays. By the time of England’s Henry IV, the royal minstrels wore

livery (a household uniform) and received a regular salary. They were re-

quired to play at fi ve major feasts, and most were to be on standby at all

other feasts. One reason for the growth of minstrel employment in great

households is that the common minstrels gained a reputation for thieving

and causing trouble. In the early Middle Ages, minstrels were always per-

mitted to come into any castle or manor, which led to abuses by enemies

posing as minstrels. Increasingly, minstrels needed licenses and letters

of recommendation. At the close of the Middle Ages, the English king

Edward IV set up a guild for minstrels to keep impostors out.

Although the best were paid well and could fi nd stable homes in the

service of lords, most minstrels walked long distances in all weather. Many

were poorly paid for public performances, especially if they had low skills or

a lack of connections. Some attached themselves to parties of pilgrims to

provide entertainment in exchange for provisions and tips. Some performed

at saints’ festivals and fairs. Minstrels were vagrants by nature, and, by the

close of the Middle Ages, cities had begun to license and regulate them. In

some periods, minstrels needed written licenses to distinguish them from

vagabonds. Most people worked in one place, but minstrels were always on

the road. The disguise of a minstrel was popular for thieves and others who

wished to be incognito.

The church ’s attitude to minstrels was usually negative. Money given

to minstrels could have been given to the poor, and minstrels encouraged

mockery and levity. Individual bishops and abbots welcomed minstrels for

their entertainment and news. A small minority of clergy studied the min-

strels’ ways, borrowing their tunes for the church. Saint Francis had trained

as a minstrel and called his friars “ ioculatores Domini .” The Franciscan tra-

dition of writing Christmas carols for the common people recognized the

power of cheerful popular music.

In Arras, a French-speaking city in Flanders, the jongleurs formed a con-

fraternity to guard a special relic of the Virgin Mary. They said that Mary

had appeared to two jongleurs and had given them a holy candle, the Sainte-

Chandelle that could heal ergotism, a disease called Saint Anthony’s fi re in

the Middle Ages. Ergotism is caused by a deadly fungus that grows on rye

in wet weather, but they did not know this; to them, it was a mysterious af-

fl iction. The jongleurs called themselves the Carité de Notre Dame des Ar-

dents, and they held three-day festivals like guilds and parishes to celebrate

their saint’s day. They put on an annual play to reenact the appearance of

Mary to two jongleurs. In this town, although jongleurs everywhere still

had reputations of loose morals, the jongleurs became a leading force in re-

ligion and even in some aspects of government. Every outbreak of ergotism

pushed the Carité and its holy candle into prominence again.

Minstrels and Troubadours

499

Troubadours

The poetry of the troubadours grew in the distinctively different cul-

ture of southern France—the regions of Aquitaine and Provence. Their

language, known as Occitan or Provençal, was a halfway point between

French and Spanish. Among their cultural differences from the rest of Eu-

rope, women had always had more rights of inheritance and sometimes

ruled as countesses or duchesses. This region had more contact with both

Muslim and Christian Spain, and their poetry may have been infl uenced

by Arabic poetry. Their nobles were knights in the full tradition of French

chivalry, but they were not Norman or Frankish in descent and were less

violent. In this culture, an alternative form of Christianity grew; it was

based in the old Arian theology to which the Visigoths had fi rst converted

in Roman times. Known as Albigensian or Cathar doctrine, the religion

was pacifi st and vegetarian and gave women full rights while insisting on

abstinence from sex.

During the 12th century, the poetry sung at the small courts of Provence,

Toulouse, Aquitaine, and Poitou elevated women to a new, powerful status.

The songs developed conventions that permitted them to express strong

feelings and make sexual innuendos without explicitly targeting or shaming

any particular women. Most songs were addressed to midons, “my lady,”

who might be the lord’s wife or any other woman. The songs addressed

her intimately and personally, as though she, listening, would know that the

song was addressed to her, without her name being used. Some used plain

language, but later troubadour poetry invented sophisticated conventions

of allusion, euphemism, and metaphor.

Scholars know little about the troubadours and their musical customs, in

spite of how widespread and infl uential they were. In 1209, the Pope pro-

claimed a Crusade against the heresy of the Albigensians (Cathars). There

was a full war against the strongholds of Toulouse and Provence, led by

England’s Simon de Montfort. Many towns were burned and massacred,

and a follow-up Inquisition led by Dominican monks questioned people

about their beliefs. The kings of France used the opportunity of a weakened

south to annex the territory. The culture of Occitania was destroyed, along

with manuscript records of troubadours. Troubadours who survived the

war fl ed to Spain and Italy. They helped spread their musical and poetical

style, but, removed from its native culture, the original art form died out

by around 1300.

Because of the Albigensian Crusade’s destruction, scholars can only guess

at how the troubadours composed and performed. Some written music and

many poems still exist, along with some medieval-era short biographies

of leading troubadours. There are some treatises that specify the rules of

the poetic conventions, but none are about the music or its performance.