Kenny Anthony. Philosophy in the Modern World: A New History of Western Philosophy. Volume 4

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

6

Epistemology

Two Eloquent Empiricists

M

ill desc ribed his System of Logic as a textbook of the doctrine that

derives all knowledge from experience. He was, therefore, a propon-

ent of empiricism, though he did not like the term. Indeed, in an import-

ant respect, he was one of the most resolute empiricists there have ever

been. He went beyond his predecessor s in claiming that not only all

science, but also all mathematics, derived from experience. The axioms of

geometry and the first principles of mathematics are, he says, ‘notwith-

standing all appearances to the contrary, results of observations and

experiences, founded, in short, on the evidence of the senses’ (SL 2.3.24.4).

The definition of each number, Mill maintained, involves the assertion

of a physical fact.

Each of the numbers two, three, four &c., denotes physical phenomena, and

connotes a physical property of those phenomena. Two, for instance, denotes all

pairs of things, and twelve all dozens of things, connoting what makes them pairs

or dozens; and that which makes them so is something physical; since it cannot be

denied that two apples are physically distinguishable from three apples, two horses

from one horse, and so forth: that they are a different visible and tangible

phenomenon. (SL 3.24.5)

He does not make clear exactly what the property is that is connoted by the

name of a number, and he admits that the senses find some difficulty in

distinguishing between 102 horses and 103 horses, however easy it may be

to tell two horses from three. Nonetheless, there is a property connoted by

numbers, namely, the characteristic manner in which the agglomeration is

made up, and may be separated into parts. For instance, collections of

objects exist, which while they impress the senses thus ; may be separated

into two parts thus . . . ‘This proposition being granted, we term all such

parcels Threes’ (SL 2.6.2).

Critics of Mill were to observe that it was a mercy that not everything in

the world is nailed down; for if it were, we should not be able to separate parts,

and two and one would not be three. It does not, on sober reflection, seem

that there is any physical fact that is asserted in the definition of a number like

777,864. But Mill’s thesis that arithmetic is essentially an empirical science does

not stand or fall with his account of the definition of numbers.

He claims, for instance, that a principle such as ‘The sums of equals are

equals’ is an inductive truth or law of nature of the highest order.

Inductive truths are generalizations based on individual experiences.

Assertions of such truths must always be to some extent tentative or

hypothetical; and so it is in this case. The principle ‘is never accurately

true, for one actual pound weight is not exactly equal to another, nor one

measured mile’s length to another; a nice balance, or more accurate

measuring instruments, would always detect some difference’ (SL 2.6.3).

Here critics said that Mill was confusing arithmetic with its applications.

But it was important for Mill to maintain that arithmetic was an empirical

science, because the alternative, that it was an a priori discipline, was the

source of infinite harm. ‘The notion that truths external to the mind may

be known by intuition or consciousness, independently of observation and

experience is, I am persuaded, in these times the great intellectual support

of false doctrines and bad institutions’ (A 134). To avoid this mischief Mill

was willing to pay a high price, and entertain the possibility that at some

future time, in some distant galaxy, it might turn out that two and two

made not four but five.

Considered as a philosopher, John Henry Newman belonged to the same

empiricist tradition as John Stuart Mill. He disliked the German metaphy-

sics that was beginning to infiltrate Oxford during his time there. ‘What a

vain system of words without ideas such men seem to be piling up,’ he

remarked. After his conversion to Rome he was equally ill at ease with the

scholastic philosophy favoured by his Catholic confre

`

res. The only direct

acquaintance we have with things outside ourselves, he asserted, comes

through our senses; to think that we have faculties for direct knowledge of

immaterial things is mere superstition. Even our senses convey us but a

EPISTEMOLOGY

145

little way out of ourselves: we have to be near things to touch them; we can

neither see nor hear nor touch things past or future. But though a staunch

empiricist, Newman gives a more exalted role to reason than it was granted

by the idealist Kant:

Now reason is that faculty of mind by which this deficiency [of the senses] is

supplied: by which knowledge of things external to us, of beings, facts, and events,

is attained beyond the range of sense. It ascertains for us not natural things only,

or immaterial only, or present only, or past or future; but even if limited in its

power, it is unlimited in its range . . . It reaches to the ends of the universe, and to

the throne of God beyond them; it brings us knowledge, whether real or

uncertain, still knowledge, in whatever degree of perfection, from every side;

John Henry

Newman, whose

Grammar of Assent,

though written to

a religious agenda,

is a classic of

epistemology in

its own right.

EPISTEMOLOGY

146

but at the same time, with this characteristic that it obtains it indirectly, not

directly. (US 199)

Reason does not actually perceive anything: it is a faculty for proceeding

from things that are perceived to things that are not. The exercise of reason

is to assert one thing on the grounds of some other thing.

Newman identifies two different operations of the intellect that are

exercised when we reason: inference (from premisses) and assent (to a

conclusion). It is important to keep in mind that these two are quite

distinct from each other. We often assent to a proposition when we have

forgotten the reasons for assent; on the other hand assent may be given

without argument, or on the basis of bad arguments. Arguments may be

better or worse, but assent either exists or not. It is true that some

arguments are so compelling that assent immediately follows inference.

But even in the cases of mathematical proof there is a distinction between

the two intellectual operations. A mathematician who has just hit upon a

complex proof would not assent to its conclusion without going over his

work and seeking corroboration from others.

Assent, as has been said, may be given without adequate evidence or

argument. This often leads to error; but is it always wrong? Locke main-

tained that it was: he gave, as a mark of the love of truth, the not

entertaining any proposition with greater assurance than the proofs it is

built on will warrant. ‘Whoever goes beyond this measure of assent, it

is plain receives not truth in the love of it, loves not truth for truth-sake,

but for some other by-end’ (Essay concerning Human Understanding, iv. xvi).

Locke maintained that there can be no demonstrable truth in concrete

matters, and therefore assent to a concrete proposition must be conditional

and fall short of certitude. Absolute assent has no legitimate exercise except

as ratifying acts of intuition or demonstration.

Newman disagrees. There are no such things as degrees of assent, he

maintains, though there is room for opinion without the assent that is

necessary for knowledge.

Every day, as it comes, brings with it opportunities for us to enlarge our circle of

assents. We read the newspapers; we look through debates in Parliament, pleadings

in the law courts, leading articles, letters of correspondents, reviews of books,

criticisms in the fine arts, and we either form no opinion at all upon the subjects

discussed, as lying out of our line, or at most we have only an opinion about

EPISTEMOLOGY

147

them ...wenever say that we give [a proposition] a degree of assent. We might as

well talk of degrees of truth as degrees of assent. (GA 115)

Nonetheless, Newman argues, assent on evidence short of intuition or

demonstration may well be legitimate, and frequently is so.

We are sure beyond all hazard of a mistake, that our own self is not the only being

existing; that there is an external world; that it is a system with parts and a whole,

a universe carried on by laws; and that the future is affected by the past. We accept

and hold with an unqualified assent, that the earth, considered as a phenomenon,

is a globe; that all its regions see the sun by turns; that there are vast tracts on it of

land and water; that there are really existing cities on definite sites, which go by the

names of London, Paris, Florence and Madrid. We are sure that Paris or London,

unless suddenly swallowed up by an earthquake or burned to the ground, is today

just what it was yesterday, when we left it. (GA 117)

Eachof us is certainthat we shall allone day die. But if we are askedfor evidence

of this, all that we can offer is circuitous argument or reductio ad absurdum.

We laugh to scorn the idea that we had no parents though we have no memory of

our birth; that we shall never depart this life, though we can have no experience

of the future; that we are able to live without food, though we have never tried;

that a world of men did not live before our time, or that that world has no

history: that there has been no rise and fall of states, no great men, no wars, no

revolutions, no art, no science, no literature, no religion. (GA 117)

On all these truths, Newman sums up, we have an immediate and

unhesitating hold, and we do not think ourselves guilty of not loving

truth for truth’s sake because we cannot reach them by a proof consisting

of a series of intuitive propositions. None of us can think or act without

accepting some truths ‘not intuitive, not demonstrated, yet sovereign’.

Though he denies that there are degrees of assent, Newman makes

a distinction between simple assent and complex assent or certitude.

Simple assent may be unconscious, it may be rash, it may be no more

than a fancy. Complex assent involves three elements: it must follow on

proof, it must be accompanied by a specific sense of intellectual content-

ment, and it must be irreversible. The feeling of satisfaction and self-

gratulation characteristic of certitude attaches not to knowledge itself,

but to the consciousness of possessing knowledge.

One difference between knowledge and certitude that is commonly

agreed among philosophers is this: If I know p, then p is true; but I may

EPISTEMOLOGY

148

be certain that p and p be false. Newman is not quite consistent on this

issue. Sometimes he talks as if there is such a thing as false certitude; at

other times he suggests that a conviction can only be a certitude if the

proposition in question is objectively true (GA 128). But whether or not

certitude entails truth, it is undeniable that to be certain of something

involves believing in its truth. It follows that if I am certain of a thing,

I believe it will remain what I now hold it to be, even if my mind should

have the bad fortune to let my belief drop. If we are certain of a belief, we

resolve to maintain it and we spontaneously reject as idle any objections to

it. If someone is sure of something, if he has such a conviction, say, that

Ireland is to the west of England, if he would be consistent, he has no

alternative but to adopt ‘magisterial intolerance of any contrary assertion’.

Of course, despite one’s initial resolution, one may in the event give up

one’s conviction. Newman maintains that anyone who loses his conviction

on any point is thereby proved never to have been certain of it.

How do we tell, then, at any given moment, what our certitudes are? No

line, Newman thinks, can be drawn between such real certitudes as have

truth for their object, and merely apparent certitudes. What looks like a

certitude always is exposed to the chance of turning out to be a mistake.

There is no interior, immediate test sufficient to distinguish genuine from

false certitudes (GA 145).

Newman correctly distinguishes certainty from infallibility. My memory

is not infallible: I remember for certain what I did yesterday but that does

not mean that I never misremember. I am quite clear that two and two

make four, but I often make mistakes in long additions. Certitude concerns

a particular proposition, infallibility is a faculty or gift. It was possible for

Newman to be certain that Victoria was queen without claiming to possess

any general infallibility.

But how can I rest in certainty when I know that in the past I have

thought myself certain of an untruth? Surely what happened once may

happen again.

Suppose I am walking out in the moonlight, and see dimly the outlines of some

figure among the trees;—it is a man. I draw nearer, it is still a man; nearer still, and

all hesitation is at an end.—I am certain it is a man. But he neither moves nor

speaks when I address him; and then I ask myself what can be his purpose in hiding

among the trees at such an hour. I come quite close to him and put out my arm.

Then I find for certain that what I took for a man is but a singular shadow, formed

EPISTEMOLOGY

149

by the falling of the moonlight on the interstices of some branches or their foliage.

Am I not to indulge my second certitude, because I was wrong in my first? Does

not any objection, which lies against my second from the failure of my first, fade

away before the evidence on which my second is founded? (GA 151)

The sense of certitude is, as it were, the bell of the intellect, and sometimes

it strikes when it should not. But we do not dispense with clocks because

on occasions they tell the wrong time.

No general rules can be set out that will prevent us from ever going

wrong in a specific piece of concrete reasoning. Aristotle in his Ethics told us

that no code of laws, or moral treatise, could map out in advance the path

of individual virtue: we need a virtue of practical wisdom (phronesis)to

determine what to do from moment to moment. So too with theoretical

reasoning, Newman says: the logic of language will take us only so far, and

we need a special intellectual virtue, which he calls ‘the illative sense’, to

tell us the appropriate conclusion to draw in the particular case.

In no class of concrete reasonings, whether in experimental science, historical

research, or theology, is there any ultimate test of truth and error in our infer-

ences besides the trustworthiness of the Illative Sense that gives them its sanction;

just as there is no sufficient test of poetical excellence, heroic action, or gentle-

man-like conduct, other than the particular mental sense, be it genius, taste, sense

of propriety, or the moral sense, to which those subject matters are severally

committed. (GA 231–2)

Newman’s epistemology has not been much studied by subsequent philo-

sophers because of the religious purpose that was his overarching aim in

developing it. But the treatment of belief, knowledge, and certainty in

The Grammar of Assent has merits that are quite independent of the theo-

logical context, and which bear comparison with classical texts of the

empiricist tradition from Locke to Russell.

Peirce on the Methods of Science

Within the decade after the publication of Newman’s Grammar, C. S. Peirce,

in America, was endeavouring to devise an epistemology appropriate to an

age of scientific inquiry. He presented it in a series of articles in the Popular

Science Monthly entitled ‘Illustration s of the Logic of Science’. The most

EPISTEMOLOGY

150

famous of the series are the two first articles, ‘The Fixation of Belief ’ and

‘How to Make our Ideas Clear’ (CP 5.358 ff., 388 ff.).

In the first essay Peirce observes that inquiry always originates in doubt,

and ends in belief.

The irritation of doubt is the only immediate motive for the struggle to obtain

belief. It is certainly best for us that our beliefs should be such as may truly guide

our actions so as to satisfy our desires; and this reflection will make us reject any

belief that does not seem to have been so formed as to insure this result. But it will

only do so by creating a doubt in the place of that belief. With the doubt, therefore,

the struggle begins, and with the cessation of doubt it ends. Hence, the sole object

of inquiry is the settlement of opinion. (EWP 126)

In order to settle our opinions and fix our beliefs, Peirce says, four different

methods are commonly used. They are, he tells us, the method of tenacity,

the method of authority, the a priori method, and the scientific method.

We may take a proposition and repeat it to ourselves, dwelling on all

that supports it and turning away from anything that might disturb it.

Thus, some people read only newspapers that confirm their political

beliefs, and a religious person may say ‘Oh, I could not believe so-and-so,

because I should be wretched if I did’. This is the method of tenacity, and it

has the advantage of providing comfort and peace of mind. It may be true,

Peirce says, that death is annihilation, but a m an who believes he will go

straight to heaven when he dies ‘has a cheap pleasure that will not be

followed by the least disappointment’.

The problem you meet if you adopt the method of tenacity is that you

may find your beliefs in conflict with those of other equally tenacious

believers. The remedy for this is provided by the second method, that of

authority. ‘Let an institution be created that shall have for its object to keep

correct doctrines before the attention of the people, to reiterate them

perpetually, and to teach them to the young; having at the same time

power to prevent contrary doctrines from being taught, advocated, or

expressed.’ This method had been most perfectly practised in Rome,

from the days of Numa Pompilius to Pio Nono, but throughout the

world, from Egypt to Siam, it has left majestic relics in stone of a sublimity

comparable to the greatest works of nature.

There are two disadvantages to the method of authority. First, it is always

accompanied by cruelty. If the burning and massacre of heretics is frowned

EPISTEMOLOGY

151

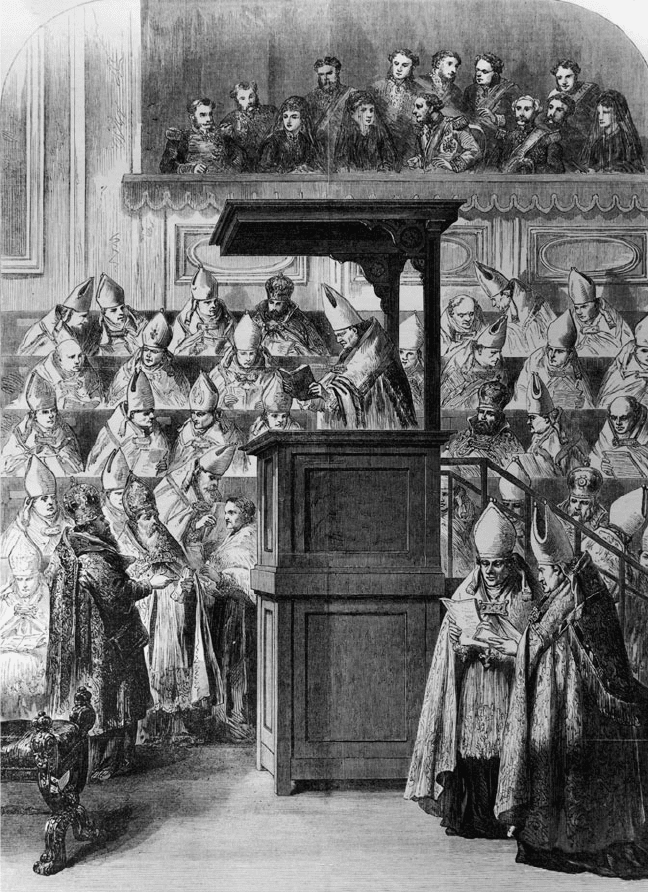

‘‘The method of authority’’ that Peirce condemned reached a high point when Pius

IX’s Vatican Council declared Popes to be infallible. The right method in epistemol-

ogy, according to Peirce, should be called, by contrast, ‘‘fallibilism’’.

EPISTEMOLOGY

152

upon in modern states, nonetheless a kind of moral terrorism enforces

uniformity of opinion. ‘Let it be known that you seriously hold a tabooed

belief and you may be perfectly sure of being treated with a cruelty less brutal

but more refined than hunting you like a wolf.’ Second, no institution can

regulate opinion on every subject, and there will always be some independ-

ent thinkers who, by comparing their own culture with others, will see that

the doctrines inculcated by authority arise only from accident and custom.

Such thinkers may adopt a third method, attempting, by a priori medi-

tation, to produce a universally valid metaphysics. This is more intellec-

tually respectable than the other two methods, but it has manifestly failed

to produce a fixation of beliefs. From earliest times to latest, the pendulum

has swung between idealist and materialist metaphysics without ever com-

ing to rest.

We must therefore adopt the fourth method, the method of science.

The first postulate of this method is the existence of a reality independent

of our minds.

There are real things, whose characters are entirely independent of our opinions

about them; those realities affect our senses according to regular laws, and, though

our sensations are as different as our relations to the objects, yet, by taking

advantage of the laws of perception, we can ascertain by reasoning how things

really are, and any man, if he has sufficient experience and reason enough about it,

will be led to the one true conclusion. (EWP 133)

The task of logic is to provide us with guiding principles to enable us to find

out, on the basis of what we know, something we do not know, and thus to

approximate ever more closely to this ultimate reality.

Though Peirce insisted that doubt was the origin of inquiry, he rejected

Descartes’s principle that true philosophy must begin from universal, metho-

dical scepticism. Genuine doubt must be doubt of a particular proposition, for

a particular reason. Cartesian doubt was no more than a futile pretence, and

the Cartesian endeavour to regain certainty by private meditation was even

more pernicious. ‘We individually cannot reasonably hope to attain the

ultimate philosophy we pursue; we can only seek it, therefore, for the

community of philosophers’ (EWP 87).

Descartes was right that the first task in philosophy is to clarify our ideas;

but he failed to give an adequate account of what he meant by clear and

distinct ideas. If an idea is to be distinct, it must sustain the test of dialectical

EPISTEMOLOGY

153