Kenny Anthony. Philosophy in the Modern World: A New History of Western Philosophy. Volume 4

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The different grades of objectification of the will are identified by

Schopenhauer with the Ideas of Plato. These too, like the will itself, are

outside space and time.

Those different grades of the will’s objectification, expressed in innumerable

individuals, exist as the unattained patterns of these, or as the eternal forms of

things. Not themselves entering into time and space, the medium of individuals,

they remain fixed, subject to no change, always being, never having become. The

particular things, however, arise and pass away; they are always becoming and

never are. (WWI 129)

The combination of Platonic idealism with Indian mysticism gives Scho-

penhauer’s system a uniquely metaphysical quality. However much they

admired his style, or admitted his influence, few philosophers felt able to

follow him all the way. There has never been a school of Schopenhauerians

as there have been schools of Kantians and Hegelians. The one person who

was willing to declare himself a disciple of Schopenhauer was the Wagner

of Tristan und Isolde.

Metaphysics and Teleology

It is a far cry from Schopenhauer’s mystical idealism to Darwin’s evolu-

tionary naturalism, and indeed it may seem odd to mention a biologist at

all in a chapter on metaphysics. But Darwin’s theories had implications,

which went beyond his immediate interests, for the general theory of

causation. Aristotle, who was the first to systematize metaphysics, did so

in terms of four kinds of causes: material, formal, efficient, and final. The

final cause was the goal or end of a structure or activity. Explanations in

terms of final causes were called ‘teleological’ after the Greek word for end,

telos. For Aristotle teleological explanations were operative at every level,

from the burrowing of an earthworm to the rotation of the heavens. Since

Darwin, many thinkers have claimed, there is no longer any room at all for

teleological explanation in any scientific discipline.

Aristotelian teleological explanations of activities and structures have

two features: they explain things in terms of their ends, not their begin-

nings, and they invoke the notion of goodness. Thus, an activity will be

explained by reference not to its starting point but to its terminus; and

METAPHYSICS

174

arrival at the terminus will be exhibited as some kind of good for the agent

whose activity is to be explained. Thus, the downward motion of heavy

bodies on earth was expla ined by Aristotle as a movement towards their

natural place, the place where it was best for them to be, and the circular

motion of the heavens was to be explained by love of a supreme

being. Similarly, teleological explanation of the development of organic

structures showed how the organ, in its perfected state, conferred a benefit

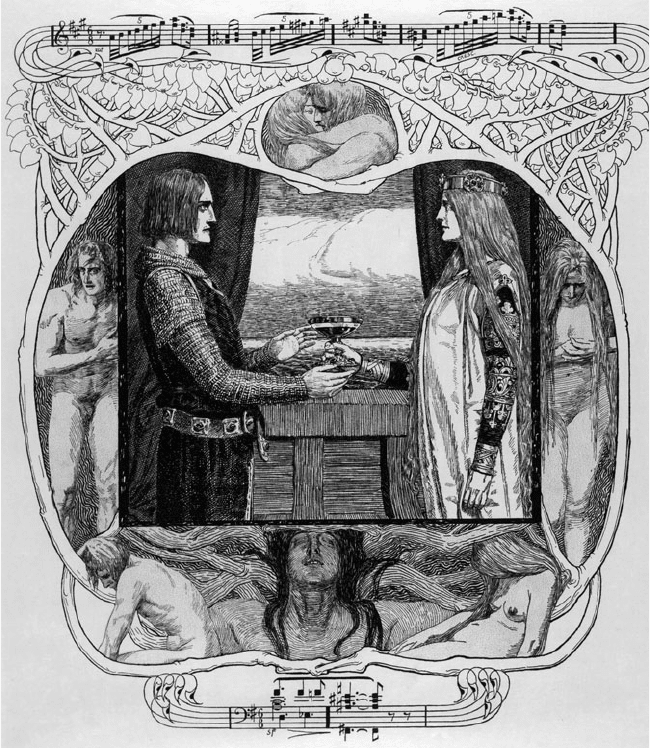

A lithograph of F. Stassen illustrates the moment in Wagner’s opera in which Isolde

hands the fateful potion to Tristan.

METAPHYSICS

175

on the complete organism. Thus, ducks grow webbed feet so that they can

swim.

Descartes rejected the use of teleological explanation in physics or

biology. Final causation, he maintained, implied in the agent a knowledge

of the end to be pursued; but such knowledge could only exist in minds.

The explanation of every physical movement and activity must be mech-

anistic; that is, it must be given in terms of initial, not final, conditions, and

those conditions must be stated in desc riptive, not evaluative, terms.

Descartes offered no good argument for his contention, and his thesis

ruled out straightforward gravitational attraction no less than the Aristo-

telian cosmic ballet. Moreover, Descartes was wrong to think that teleo-

logical explanation must involve conscious purpose: whatever Aristotle

may have thought about the heavenly bodies, he never believed that an

earthworm, let alone a falling pebble, was in possession of a mind.

It was not Descartes, but Newton and Darwin, who dealt the serious

blows to Aristotelian teleology, by undermining, in different ways, its two

constituent elements. Newtonian gravity, no less than Aristotelian motion,

provides an explanation by reference to a terminus: gravity is a centripetal

force, a force ‘by which bodies are drawn, or impelled, or in any way tend,

towards a point as to a centre’. But Newton’s explanation is fundamentally

different from Aristotle’s in that it involves no suggestion that it is in any

way good for a body to arrive at the centre to which it tends.

Darwinian explanations in terms of natural selection, on the other hand,

resemble Aristotle’s in demanding that the terminus of the process to be

explained, or the complexity of the structure to be accounted for, shall be

something that is beneficial to the relevant organism. But unlike Aristotle,

Darwin explains the processes and the structures, not in terms of a pull by

the final state or perfected structure, but in terms of the pressure of the

initial conditions of the system and its environment. The red teeth and red

claws involved in the struggle for existence were, of course, in pursuit of

a good, namely the survival of the individual organism to which they

belonged; but they were not in pursuit of the ultimate good that is to be

explained by selection, namely, the survival of the fittest species. It is thus

that the emergence of particular sp ecies in the course of evolution could be

explained not only without appeal to a conscious designer, but without

evoking teleology at all.

METAPHYSICS

176

It is, of course, only at one particular level that Darwin’s system offers to

render teleology superfluous. Human beings, such as husbandmen, act for

the sake of goals not only in breeding improved stock, but in human life

and business in general. Others among the higher animals not only act on

instinct, but pursue goals learnt by experience. Moreover, Darwinian

scientists have not given up the search for final causes. Indeed, contem-

porary biologists are much more adept at discerning the function of

structures and behaviours than their predecessors in the period between

Descartes and Darwin. What Darwin did was to make teleological explan-

ation respectable by offering a general recipe for translating it into an

explanation of a mechanistic form. His successors thus feel able freely to

use such explanations, without offering more than a promissory note

about how they are to be reduced to mechanism in any particular case.

Once they have identified the benefit, G, that an activity or structure

confers on an organism, they feel entitled to say without further ado

that ‘the organism evolved in such a way that G’.

Two great questions about teleology are left unanswered by the work of

Darwin. First, are the free and conscious decisions of human beings

irreducibly teleological, or can they be given an explanation in mechanistic

terms? There are those who believe that when more is known about the

human brain it will be possible to show that every human thought and

action is the outcome of mechanistic physical processes. This belief, how-

ever, is an act of faith; it is not the result of any scientific discovery or of any

philosophical analysis.

Second, if we assume that broadly Darwinian explanations can be found

for the existence of the teleological organisms we see around us, does our

investigation rest there? Or can the universe itself be regarded as a system

that operates, through mechanistic means, to the goal of producing species

of organisms, in the way that a refrigerator works through mechanistic

means to the goal of a uniform temperature? Is the universe itself one huge

machine, a goal-directed system?

Biologists are divided whether evolution itself has a direction. Some

believe that it has an inbuilt tendency to produce organisms of ever greater

complexity and ever higher consciousness. Others claim that there is no

scientific evidence that evolution has any kind of privileged axis. Either

way, the question remains whether it is teleological explanation or mech-

anistic explanation that is the one that operates at a fundamental level of

METAPHYSICS

177

the universe. If God created the world, then mechanistic explanation is

underpinned by teleological explanation; the fundamental explanation of

the existence and operation of any creature is the purpose of the creator. If

there is no God, but the universe is due to the operation of necessary laws

upon blind chance, then it is the mechanistic level of explanation that is

fundamental. So far as I know, no one, whether scientist or philosopher,

has provided a definitive answer to this question.

Realism vs. Nominalism

Throughout the history of philosophy one metaphysical problem recurs

again and again, presented in different terms. This is the question whether,

if we are to make sense of the world we live in, there must exist, outside the

mind, entities of a quite different kind from the fleeting individuals that we

meet in everyday existence. In the ancient world, Plato and Aristotle

discussed whether or not there were Ideas or Forms existing independently

of matter and material objects. Throughout the Middle Ages, realist and

nominalist philosophers disputed whether universals were realities or mere

symbols. In the modern era philosophers of mathematics have conducted a

parallel debate about the nature of mathematical objects, with formalists

identifying numbers with numerals, and realists asserting that numbers

have an independent reality, constituting a third world separate from the

world of mind and the world of matter.

The most vociferous defender of realism in modern times is Frege. In a

lecture entitled ‘Formal Theories of Arithmetic’ (CP 112–21) he attacks

the idea that signs for numbers, like ‘

1

⁄

2

’ and ‘’, are merely empty signs

designating nothing. Even calling them ‘signs’, he says, already suggests

that they do signify something. A resolute formalist should call them

‘shapes’. If we took seriously the contention that ‘

1

⁄

2

’ does not designate

anything, then it is merely a splash of printer’s ink or a splurge of chalk,

with various physical and chemical properties. How can it possibly have the

property that if added to itself it yields 1? Shall we say that it is given this

property by definition? A definition serves to connect a sense with a word;

but this sign was supposed to have no content. Sure, it is up to us to give a

signification to a sign, and therefore it is partly dependent on human

METAPHYSICS

178

choice what properties the content of a sign has. But these properties are

properties of the content, not of the sign itself, and hence, according to the

formalist, they will not be properties of the number. What we cannot do is

to give things properties merely by definition.

In the Grundgesetze Frege uses against the formalists the kind of argument

that Wyclif used against the nominalists of the Middle Ages.3

One cannot by pure definition magically conjure into a thing a property that in

fact it does not possess—save that of now being called by the name with which one

has named it. That an oval figure produced on paper with ink should by a

definition acquire the property of yielding one when added to one, I can only

regard as a scientific superstition. One could just as well by a pure definition make

a lazy pupil diligent. (BLA 11)

For Frege, not only numbers but functions too were mind-independent

realities. Consider an expression such as ‘2x

2

þ x’. This expression splits into

two parts, a sign for an argument and an expression for a function. In the

expressions

(2 1

2

) þ 1

(2 4

2

) þ 4

(2 5

2

) þ 5

we can recognize the same function occurring over and over again, but

with different arguments, namely 1, 4, and 5. The content that is common

to these expressions is what the function is. It can be represented by

‘2( )

2

þ ( )’, that is, by what is left of ‘2x

2

þ x’ if we leave the xs out. The

argument is not part of the function, rather it combines with the function

to make a complete whole. A function must be distinguished from its value

for a particular argument: the value of a mathematical function is always a

number, as the number 3 is the value of our function for the argument 1,

so that ‘(2 1

2

) þ 1’ names the number 3. A function itself, unlike the

numbers that are its arguments and its values, is something incomplete, or

‘unsaturated’ as Frege calls it. That is why it is best represented, symbolic-

ally, by a sign containing gaps. In itself, it is not a sign but a reality lying

behind the sign.

It was not only in mathematics that Frege was a resolute realist. He

extended the notion of function in such a way that all concepts of any kind

3 See vol. II, pp. 152–3.

METAPHYSICS

179

turn out to be functions. The link between mathematical functions and

predicates such as ‘...killed ...’ or ‘...is lighter than ...’ is made in a

striking passage of ‘Function and Concept’ where we are invited to consider

the function ‘x

2

¼ 1’.

The first question that arises here is what the values of this function are for

different arguments. Now if we replace x successively by 1, 0, 1, 2 we get:

(1)

2

¼ 1

0

2

¼ 1

1

2

¼ 1

2

2

¼ 1

Of these equations the first and third are true, the others false. I say ‘the value of

our function is a truth-value’ and distinguish between the truth-values of what is

true and what is false. (CP 144)

Once this move has been made, it is possible for Frege to define a concept as

a function whose value for every argument is a truth-val ue. A concept will

then be the extra-linguistic counterpart of a predicate in language: what is

represented, for instance, by the predicate ‘...is a horse.’ Concepts, like

numbers, are quite independent of mind or matter: we do not create them,

we discover them; but we do not discover them by the operation of our

senses. They are objective, though they do not have the kind of reality

(Wirklichkeit) that belongs to the physical world of cause and effect.

Frege’s realism is often called Platonism, but there is a significant

difference between Plato’s Ideas and Frege’s concepts. For Plato, the Ideal

Horse was itself a horse: only by being itself a horse could it impart

horsiness to the non-ideal horses of the everyday world.4 Frege’s concept

horse, by contrast, is something very unlike a horse. Any actual horse is an

object, and between objects and concepts there is, for Frege, a great gulf

fixed. Not only is the concept horse not a horse, it is, Frege tells us, not a

concept. This remark at first hearing brings us up short; but there is

nothing really untoward about it. Prefacing ‘horse’ with ‘the concept’ has

the effect of turning a sign for a concept into a sign for an object, just as

putting quotation marks round the word ‘swims’ turns the sign for a verb

into a noun which, unlike a verb, can be the subject of a sentence. We can

4 See vol. I, p. 208.

METAPHYSICS

180

say truly ‘ ‘‘swims’’ is a verb’, but also ‘ ‘‘ ‘‘swims’’ ’’ is a noun’. That is the

clue to understanding Frege’s claim that the concept horse is not a concept.

First, Second, and Third in Peirce

In the English-speaking world, the most original system of metaphysics

devised in the nineteenth century was that of C. S. Peirce. It is true that

Peirce’s principle of pragmatism resembles the verification principle of the

logical positivists, and that from time to time he was willing to denounce

metaphysics as ‘meaningless gibberish’; nonetheless, he himself constructed

a system that was as abstruse and elaborate as anything to be found in the

writings of German idealists.

Like Hegel, Pierce was fascinated by triads. He wrote in The Monist in 1891:

Three conceptions are perpetually turning up at every point in every theory of

logic, and in the most rounded systems they occur in connection with one

another. They are conceptions so very broad and consequently indefinite that

they are hard to seize and may be easily overlooked. I call them the conceptions of

First, Second, Third. First is the conception of being or existing independent of

anything else. Second is the conception of being relative to, the conception

of reaction with, something else. Third is the conception of mediation, whereby

a first and second are brought into relation. (EWP 173)

This triadic system was inspired by Peirce’s research into the logic of

relations. He classified predicates according to the number of items to

which they relate. ‘...is blue’ is a monadic or one-place predicate, ‘ . . . is

thesonof...’,with two places, is dyadic, and ‘...gives ...to...’istriadic.

A sense-impression of a quality is an example of a ‘firstness’, heredity is an

example of a ‘secondness’. The third class of items can be exemplified by the

relationship whereby a sign signifies (‘mediates’) an object to an interpre-

ting mind. Universal ideas are a paradigm case of thirdness, and so are laws

of nature. If a spark falls into a barrel of gunpowder (first) it causes an

explosion (second) and does so according to a law that mediates between

the two (third).

Peirce was willing to apply this triadic classification very widely, to

psychology and to biology as well as to physics and chemistry. He even

employed it on a cosmic scale: in one place he wrote ‘Mind is First, Matter

METAPHYSICS

181

is Second, Evolution is Third’ (EWP 173). Moreover, he offered an elaborate

proof that while a scientific language must contain monadic, dyadic, and

triadic predicates, there are no phenomena that require four-place predi-

cates for their expression. Expressions containing such predicates can

always be translated into expressions containing only predicates of the

three basic kinds.

Thirdness, however, Peirce sees as an irreducible element of the universe,

neglected by nominalist philosophers, who refused to accept the reality of

universals. The aim of all scient ific inquiry is to find the thirdness in the

variety of our experience—to discover the patterns, regularities, and laws

in the world we live in. But we should not be looking for universal,

exceptionless laws that determine all that happens. The doctrine of neces-

sity, indeed, was one of Peirce’s chief targets in his criticism of the Weltan-

schauung of nineteenth-century science. He states it thus:

The proposition in question is that the state of things existing at any time, together

with certain immutable laws, completely determine the state of things at every

other time (for a limitation to future time is indefensible). Thus, given the state of

the universe in the original nebula, and given the laws of mechanics, a sufficiently

powerful mind could deduce from these data the precise form of every curlicue of

every letter I am now writing. (EWP 176)

This proposition, Peirce thought, was quite indefensible. It could be put

forward neither as a postulate of reasoning nor as the outcome of obser-

vation. ‘Try to verify any law of nature and you will find that the more

precise your observations, the more certain they will be to show irregular

departures from the law’ (EWP 182). Peirce maintained that there was an

irreducible element of chance in the universe: a thesis which he called

‘tychism’ from the Greek word for chance, ı. In support of tychism he

enlisted both Aristotle and Darwin. The inclusion of chance as a possible

cause, he said, was of the utmost essence of Aristotelianism; and the only

way of accounting for the laws of nature was to suppose them results of

evolution. ‘This supposes them not to be absolute, not to be obeyed

precisely. It makes an element of indeterminacy, spontaneity, or absolute

chance in nature’ (EWP 163). Thus, there was ample room for belief in the

autonomy and freedom of the human will.

There were, Peirce thought, three ways of explaining the relationship

between physical and psychical laws. The first was neutralism, which

METAPHYSICS

182

placed them on a par as independent of each other. The second was

materialism, which regarded psychical laws as derived from physical

ones. The third was idealism, which regarded psychical laws as primordial

and physical laws as derivative. Neutralism, he thought, was ruled out by

Ockham’s razor: never look for two explanatory factors where one will do.

Materialism involved the repugnant idea that a machine could feel. ‘The

one intelligible theory of the universe is that of objective idealism, that

matter is effete mind, inveterate habits becoming physical laws’ (EWP 168).

Peirce offered to explain the course of the universe in terms of firstness,

secondness, and thirdness. ‘Three elements are active in the world’, he

wrote; ‘first, chance; second, law; and third, habit-taking’ (CP i. 409). In the

infinitely remote beginning, there was nothing but unpersonalized feeling,

without any connection of regularity. Then, the germ of a generalizing

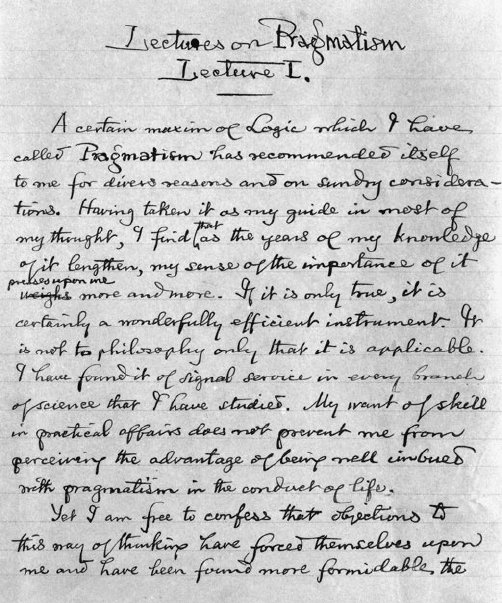

A lecture

manuscript of

Peirce, which il-

lustrates the

curlicues that he

believedtobeun-

predictable by

deterministic

laws.

METAPHYSICS

183