McConnell Campbell R., Brue Stanley L., Barbiero Thomas P. Microeconomics. Ninth Edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

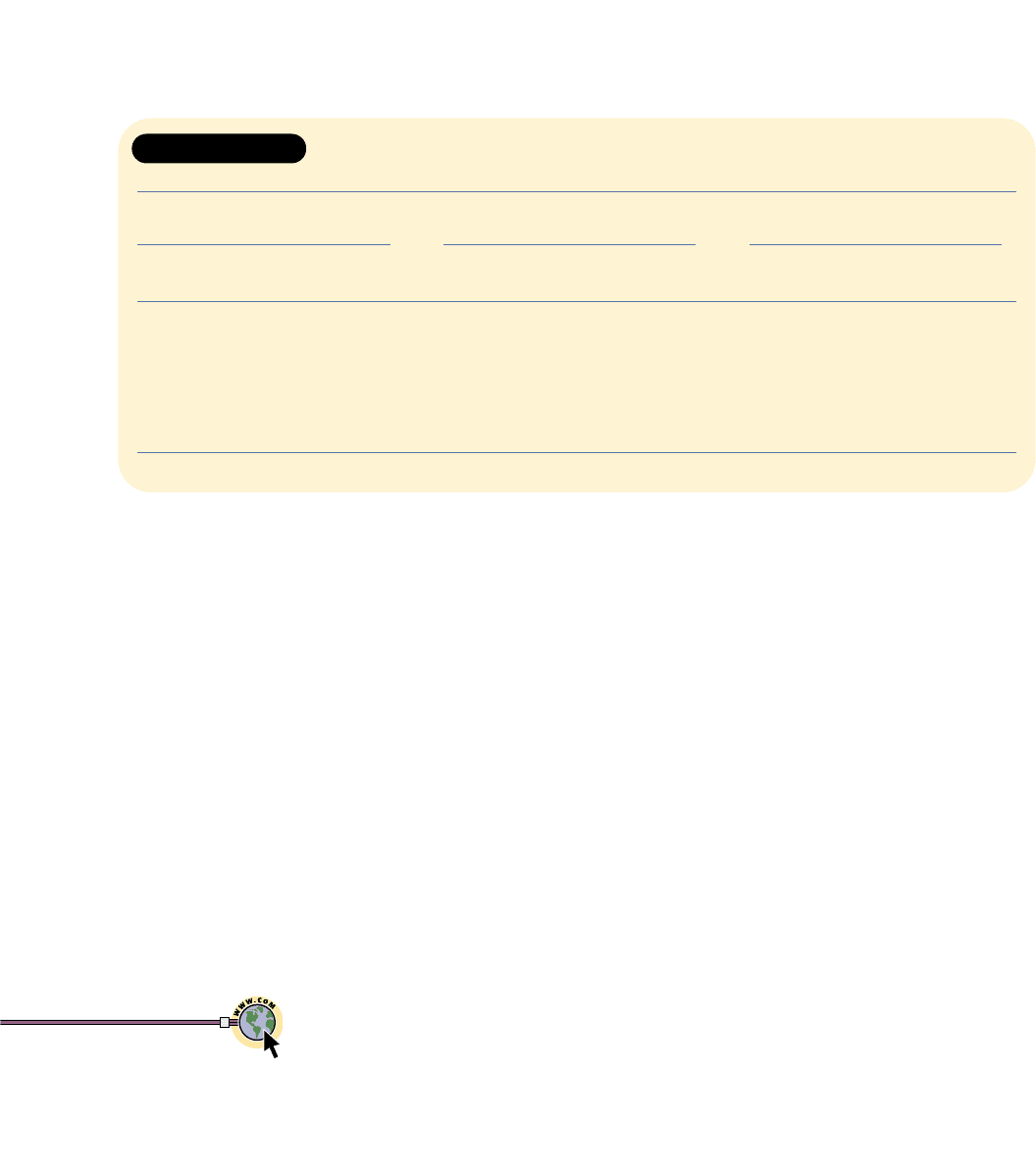

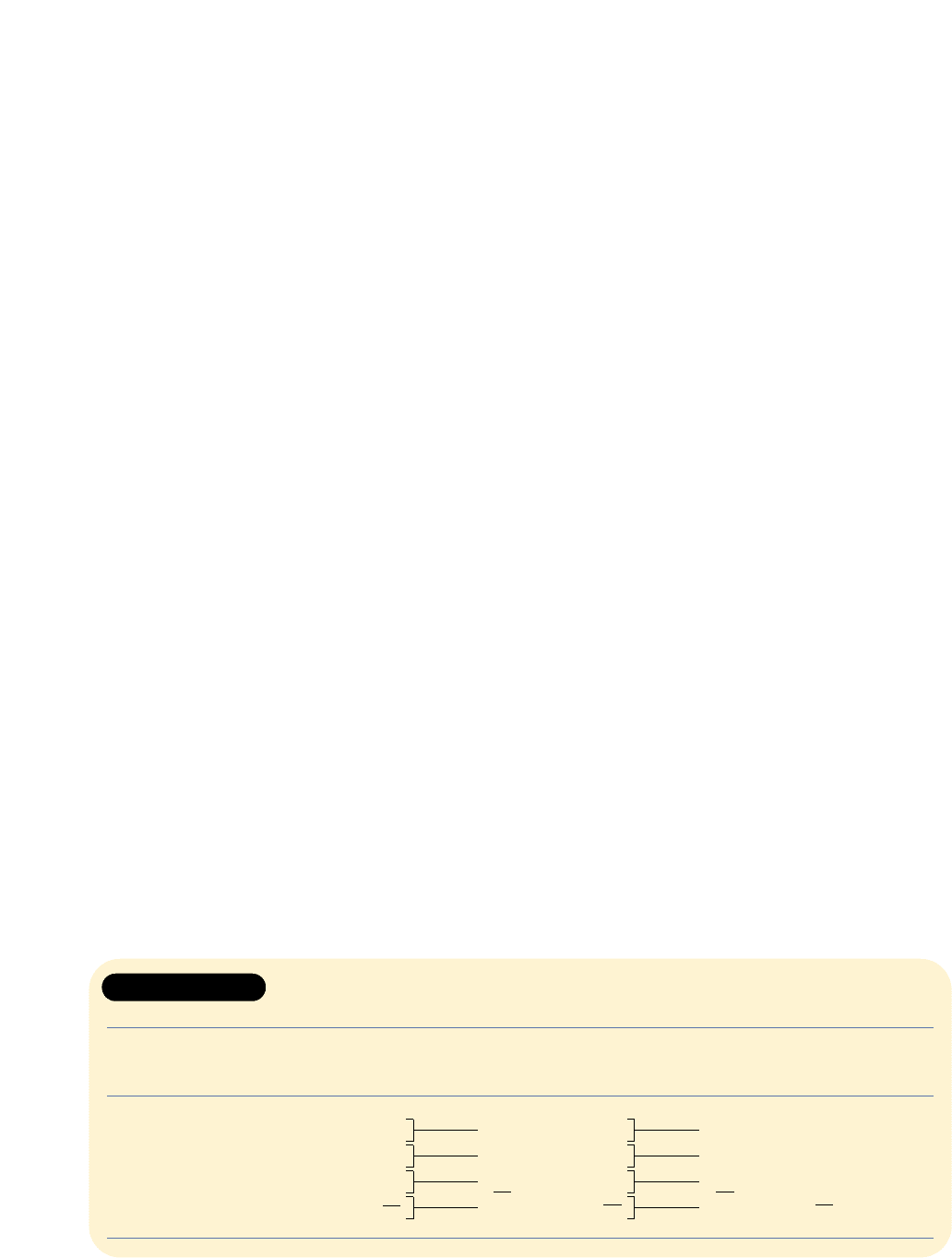

income of $16,000, transfer payments are zero. The level of earned income at which

the transfer payments disappear is called the break-even income.

We might criticize plan 1 on the grounds that a 50 percent benefit-reduction rate

is too high and therefore does not provide sufficient incentives to work. As earned

income increases, the loss of transfer payments constitutes a tax on earnings. Some

people may choose not to work when they lose 50 cents of each extra dollar earned.

Thus in plan 2 the $8,000 minimum income is retained, but the benefit-reduction

rate is reduced to 25 percent. But note that the break-even level of income increases

to $32,000, so many more families would now qualify for transfer payments. Fur-

thermore, a family with any earned income under $32,000 will receive a larger total

transfer payment. For both reasons, a reduction of the benefit–loss rate to enhance

work incentives will raise the cost of the income-maintenance plan.

After examining plans 1 and 2, we might argue that the $8,000 minimum annual

income is too low—it does not get families out of poverty. Plan 3 raises the mini-

mum income to $12,000 and retains the 50 percent benefit-reduction rate of plan 1.

While plan 3 does a better job of raising the incomes of the poor, it too yields a

higher break-even income than plan 1 and therefore will be more costly. Also, if the

$12,000 income guarantee of plan 3 were coupled with plan 2’s 25 percent benefit-

reduction rate to strengthen work incentives, the break-even income level would

shoot up to $48,000 and add even more to the costs of the public assistance program.

Conflicts among Goals

Clearly, the goals of eliminating poverty, maintaining work incentives, and holding

down program costs are in conflict.

Plan 1, with a low minimum income and a high benefit-reduction rate, keeps cost

down. But the low minimum income means that this plan is not very effective in

eliminating poverty, and the high benefit-reduction rate weakens work incentives.

In comparison, plan 2 has a lower benefit-reduction rate and therefore stronger

work incentives. But it is more costly because it sets a higher break-even income and

therefore pays benefits to more families.

Compared with plan 1, plan 3 has a higher minimum income and is more effec-

tive in eliminating poverty. While work incentives are the same as those in plan 1, the

higher guaranteed income in plan 3 makes the plan more costly. (Key Question 9)

chapter seventeen • income inequality and poverty 451

<www.un.org/esa/

socdev/poverty.htm>

UN declares 1997–2006

the Decade for the

Eradication of Poverty

TABLE 17-5 TRADEOFFS AMONG GOALS: THREE PUBLIC

ASSISTANCE PLANS

Plan 1 ($8,000 minimum income Plan 2 ($8,000 minimum income Plan 3 ($12,000 minimum income

and 50% benefit-reduction rate) and 25% benefit-reduction rate) and 50% benefit-reduction rate)

Earned Transfer Total Earned Transfer Total Earned Transfer Total

income payment income income payment income income payment income

$ 0 $8,000 $ 8,000 $ 0 $8,000 $ 8,000 $ 0 $12,000 $12,000

4,000 6,000 10,000 8,000 6,000 14,000 8,000 8,000 16,000

8,000 4,000 12,000 16,000 4,000 20,000 16,000 4,000 20,000

12,000 2,000 14,000 24,000 2,000 26,000 24,000* 12,000 24,000

16,000* 0 16,000 32,000* 0 32,000

*Indicates break-even income. Determined by dividing the minimum income by the benefit-reduction rate.

452 Part Three • Microeconomics of Resource Markets

Poor people in 60 countries were

asked to analyze and share their

ideas of well-being (a good ex-

perience of life) and “ill-being”

(a bad experience of life).

Well-being was variously de-

scribed as happiness, harmony,

peace, freedom from anxiety,

and peace of mind. In Russia

people say, “Well-being is a life

free from daily worries about

lack of money.” In Bangladesh,

“to have a life free from anxi-

ety.” In Brazil, “not having to go

through so many rough spots.”

People describe ill-being as

lack of material things, as bad

experiences, and as bad feel-

ings about oneself. A group of

young men in Jamaica ranks

lack of self-confidence as the

second biggest impact of

poverty: “Poverty means we

don’t believe in [ourselves], we

hardly travel out of the commu-

nity—so frustrated, just locked

up in a house all day.”

Universal Problems

Although the nature of ill-being

and poverty varies among loca-

tions and people—something

that policy responses must take

into account—there is a striking

commonality across countries.

Not surprising, material well-

being turns out to be very im-

portant. Lack of food, shelter,

and clothing is mentioned every-

where as critical. In Kenya a man

says: “Don’t ask me what

poverty is because you have met

it outside my house. Look at the

house and count the number of

holes. Look at my utensils and

the clothes I am wearing. Look at

everything and write what you

see. What you see is poverty.”

Alongside the material, phys-

ical well-being features promi-

nently in the characterizations of

poverty. And the two meld to-

gether when lack of food leads

to ill health—or when ill health

leads to an inability to earn in-

come. People speak about the

importance of looking well fed.

In Ethiopia poor people say, “We

are skinny,” “We are deprived

and pale,” and speak of life that

“makes you older than your

age.”

More Than Material Goods

Security of income is also

closely tied to health. But inse-

curity extends beyond ill health.

Crime and violence are often

mentioned by poor people. In

Ethiopia women say, “We live

hour to hour,” worrying about

whether it will rain. An Argen-

tine says, “You have work, and

you are fine. If not, you starve.

That’s how it is.” Two social as-

pects of ill-being and poverty

also emerged. For many poor

people, well-being means the

freedom of choice and action

and the power to control one’s

life. A young woman in Jamaica

says that poverty is “like living in

jail, living in bondage, waiting to

be free.”

Linked to these feelings are

definitions of well-being as so-

cial well-being and comments

on the stigma of poverty. As an

old woman in Bulgaria says, “to

be well means to see your

grandchildren happy and well

dressed and to know that your

children have settled down; to

be able to give them food and

money whenever they come to

see you, and not to ask them

for help and money.” A Somali

proverb captures the other side:

“Prolonged sickness and per-

sistent poverty cause people to

hate you.”

Source: World Development Report

2000–2001, “Introduction,”(Oxford

University Press, New York, 2000),

<www.worldbank.org/poverty/wdr

poverty/report/ch1.pdf>.

POVERTY IN THE VOICES OF

POOR PEOPLE

While statistics tell us much about poverty and inequality,

the statements below attest to the human suffering

caused by insufficient material means in many nations.

chapter summary

chapter seventeen • income inequality and poverty 453

1. The distribution of income in Canada reflects

considerable inequality. After taxes, the top

20 percent of families earn 41.4 percent of

total income, while the bottom 20 percent

earn only 5.5 percent.

2. The Lorenz curve shows the percentage of

total income received by each percentage of

families. The extent of the gap between the

Lorenz curve and a line of total equality illus-

trates the degree of income inequality.

3. Recognizing that the positions of individual

families in the distribution of income change

over time and incorporating the effects of

noncash transfers and taxes would reveal less

income inequality than do standard census

data. Government transfers (cash and non-

cash) greatly lessen the degree of income

inequality; taxes also reduce inequality but

not nearly as much as transfers.

4. Absolute poverty occurs when the basic

material needs are not met. Relative poverty

refers to an individual’s or a family’s low

income relative to the rest of society. Absolute

poverty can be eradicated, but relative

poverty is much more difficult to resolve.

5. Causes of income inequality include differ-

ences in abilities, education and training, and

job tastes, along with discrimination, inequal-

ity in the distribution of wealth, and an un-

equal distribution of market power.

6. The basic argument for income equality is

that it maximizes consumer satisfaction (total

utility) from a particular level of total income.

The main argument for income inequality is

that it provides the incentives to work, invest,

and assume risk; it is necessary for the pro-

duction of output that, in turn, creates income

that is then available for distribution.

7. Current statistics suggest that about 17.5 per-

cent of the country lives in poverty. Poverty is

concentrated among the poorly educated, the

aged, and families headed by women.

8. Our present income maintenance system is

made up of social insurance programs

(Canada Pension Plan and employment insur-

ance benefits), universal programs (Old Age

Security Pension), and public assistance or

welfare programs.

9. Public assistance programs (welfare) are

difficult to design because their goals of

reducing property, maintaining work incen-

tives, and holding down program costs often

conflict.

terms and concepts

income inequality, p. 438

Lorenz curve, p. 438

income mobility, p. 440

noncash transfers, p. 440

tradeoff between equality and

efficiency, p. 446

absolute poverty, p. 447

relative poverty, p. 447

Canada Pension Plan (CPP),

p. 449

Old Age Security (OAS),

p. 449

Guaranteed Income

Supplement (GIS), p. 450

employment insurance, p. 450

study questions

1. Using quintiles, briefly summarize the degree

of income inequality in Canada.

2.

KEY QESTION Assume Syed, Beth,

Sabine, David, and Mikkel receive incomes

of $500, $250, $125, $75, and $50 respec-

tively. Construct and interpret a Lorenz curve

for this five-person economy. What percent-

age of total income is received by the richest

quintile and by the poorest quintile?

3. Why is the lifetime distribution of income

more equal than the distribution in any spe-

cific year?

4.

KEY QUESTION Briefly discuss the

major causes of income inequality. With

respect to income inequality, is there any dif-

ference between inheriting property and

inheriting a high IQ? Explain.

5. Use the leaky-bucket analogy to discuss the

equality–efficiency tradeoff.

6. Should a nation’s income be distributed to

its members according to their contributions

to the production of that total income or

according to the members’ needs? Should

society attempt to equalize income or

454 Part Three • Microeconomics of Resource Markets

economic opportunities? Are the issues of

equity and equality in the distribution of in-

come synonymous? To what degree, if any,

is income inequality equitable?

7. Analyze in detail: “There need be no tradeoff

between equality and efficiency. An efficient

economy that yields an income distribution

many regard as unfair may cause those with

meagre income rewards to become discour-

aged and stop trying. Hence, efficiency is un-

dermined. A fairer distribution of rewards

may generate a higher average productive

effort on the part of the population, thereby

enhancing efficiency. If people think they are

playing a fair economic game and this belief

causes them to try harder, an economy with

an equitable income distribution may be effi-

cient as well.

”

8. Comment on or explain:

a. “To endow everyone with equal income

will certainly make for very unequal

enjoyment and satisfaction.”

b. “Equality is a superior good: the richer we

become, the more of it we can afford.”

c. “The mob goes in search of bread, and

the means it employs is generally to wreck

the bakeries.”

d. “Some freedoms may be more important

in the long run than freedom from want

on the part of every individual.”

e. “Capitalism and democracy are really a

most improbable mixture. Maybe that

is why they need each other—to put

some rationality into equality and some

humanity into efficiency.”

f. “The incentives created by the attempt to

bring about a more equal distribution of

income are in conflict with the incentives

needed to generate increased income.”

9.

KEY QUESTION The following table

contains three hypothetical public assistance

plans.

a. Determine the minimum income, the

benefit-reduction rate, and the break-even

income for each plan.

b. Which plan is the most costly? the least

costly? Which plan is the most effective

in reducing poverty? the least effective?

Which plan embodies the strongest dis-

incentive to work? the weakest disincen-

tive to work?

c. Use your answers in part b to explain the

following statement: “The dilemma of

public assistance is that you cannot bring

families up to the poverty level and

simultaneously preserve work incentives

and minimize program costs.”

10. (The Last Word) How do poor people

describe “well being” and “ill-being”?

internet application questions

1. Statistics Canada at <www.statcan.ca/english/

Pgdb/People/Famili.htm#inc> compiles infor-

mation about low income in Canada. Use

that site to answer the following questions:

a. Is the percentage of the population living

below Statistics Canada’s low income cut-

off higher or lower than in the previous

year reported? Compared to a decade

earlier?

b. Is the poverty rate (in percent) higher or

lower than the previous year for the gen-

eral population and children under 18

and the elderly?

Plan One Plan Two Plan Three

Earned Transfer Total Earned Transfer Total Earned Transfer Total

income payment income income payment income income payment income

$ 0 $4,000 $4,000 $ 0 $4,000 $ 4,000 $ 0 $8,000 $ 8,000

2,000 3,000 5,000 4,000 3,000 7,000 4,000 6,000 10,000

4,000 2,000 6,000 8,000 2,000 10,000 8,000 4,000 12,000

6,000 1,000 7,000 12,000 1,000 13,000 12,000 2,000 14,000

IN THIS CHAPTER

IN THIS CHAPTER

Y

Y

OU WILL LEARN:

OU WILL LEARN:

To distinguish between a

public and private good.

•

How to determine the optimal

amount of a public good.

•

The nature of externalities and

the ways of dealing with them.

•

About information failures.

Government

and Market

Failure

T

he economic activities of government

affect your well-being every day. If you

drive to work or to school, you are using

publicly provided highways and streets. If

you attend a college or university, taxpayers

subsidize your education. When you receive

a cheque from your job, you see deductions

for income taxes and social insurance taxes.

Government antipollution laws affect the air

you breathe. Laws requiring seat belts and

motorcycle helmets and the sprinkler system

in university dormitories are all government

mandates.

EIGHTEEN

In this chapter we examine market failure—a circumstance in which private markets

do not bring about the allocation of resources that best satisfies society’s wants.

Where private markets fail, an economic role for government may arise. In this

chapter we examine how government responds to three types of market failure:

public goods, externalities, and information asymmetries. Our discussion of exter-

nalities in turn opens the way for a discussion of pollution and pollution policies.

In Chapter 19 our discussion of the microeconomics of government continues

with an analysis of potential government inefficiencies—called government failure—

and the economics of taxation.

Recall from Chapter 4 that a private good is divisible because it comes in units small

enough for individual buyers to afford. It is also subject to the exclusion principle: peo-

ple unwilling or unable to pay for the product are barred from obtaining its benefits.

Because of these characteristics, the demand for a private good gets expressed in the

marketplace, and profit-seeking suppliers satisfy that demand. In contrast, a public

good is indivisible and does not fit the exclusion principle. Once a producer has pro-

vided a public good, it cannot bar those who don’t pay from obtaining the benefits.

Consequently, the demand for the good is understated in the marketplace, and firms

thus lack a profit incentive to offer it for sale. If the good is to exist at all, government

will have to provide it. Two simple examples will help clarify these ideas.

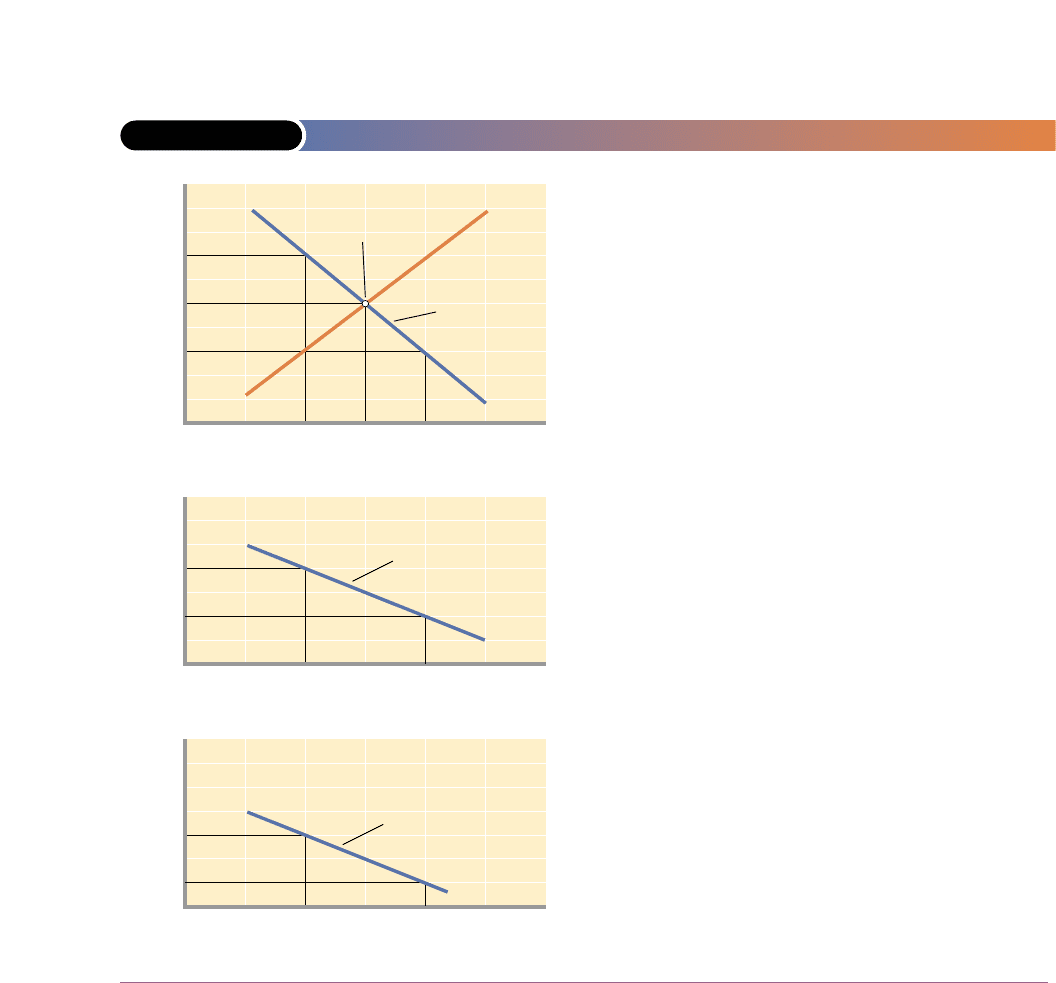

The market demand for a private good is the horizontal summation of the

demand curves representing all individual buyers (review Table 3-2 and Figure 3-

2). Suppose just two people in society enjoy hot dogs, which cost $.80 each to pro-

duce. If Adams wants to buy three hot dogs at $1 each and Benson wants to buy two

hot dogs at that same price, the market demand curve will reflect that five hot dogs

are demanded at a $1 price. A seller charging $1 for each hot dog can gain $5 of rev-

enue and earn $1 of profit ($5 of total revenue minus $4 of cost).

The situation is different with public goods. Suppose an enterprising sculptor

creates a piece of art costing $600 and places it in the town square. Also suppose that

Adams gets $300 of enjoyment from the art and Benson gets $400. Sensing this

enjoyment and hoping to make a profit, the sculptor approaches Adams for a dona-

tion equal to his satisfaction. Adams falsely says that, unfortunately, he doesn’t

much like the piece. The sculptor then tries Benson, hoping to get $400 or so. Same

deal: Benson professes not to like the piece either. Adams and Benson have become

free riders. Although feeling a bit guilty, both reason that it makes no sense to pay for

something when you can receive the benefits without paying for them. The artist is

a quick learner; he vows never to try anything like that again.

Generalization: Because of the free-rider problem, the market demand for a pub-

lic good is nonexistent or significantly understated. Where a producer cannot

exclude those who do not pay from receiving the benefits from a good, it is difficult,

if not impossible, for the producer to profitably offer the good for sale. Government

will have to provide it.

Demand for Public Goods

If consumers need not reveal their true demand for a public good in the marketplace,

then how can the optimal amount of that good be determined? The answer is that the

government has to try to estimate the demand for a public good through surveys or

public votes. Suppose Adams and Benson are the only two people in the society, and

their marginal willingness to pay for a public good, this time national defence, is as

chapter eighteen • government and market failure 457

Public Goods

<members.aol.com/

trajcom/private/

commons.htm>

The commons

The Role of

Governments

shown in columns 1, 2, and 3 in Table 18-1. Econ-

omists might have discovered these schedules

through a survey asking hypothetical questions

about how much each citizen was willing to pay

for various types and amounts of public goods

rather than go without them.

Notice that the schedules in Table 18-1 are

price–quantity schedules, implying that they

are demand schedules. Rather than depicting

demand in the usual way—the quantity of a

product someone is willing to buy at each pos-

sible price—these schedules show the price

someone is willing to pay for the marginal unit

of each possible quantity. That is, Adams is will-

ing to pay $4 for the first unit of the public good,

$3 for the second, $2 for the third, and so on.

Suppose the government produces one unit of this public good. Because the

exclusion principle does not apply, Adams’s consumption of the good does not pre-

clude Benson from also consuming it, and vice versa. So both consume the good, and

neither volunteers to pay for it. But from Table 18-1 we can find the amount these two

people would be willing to pay, together, rather than do without this one unit of the

good. Columns 1 and 2 show that Adams would be willing to pay $4 for the first unit

of the public good; columns 1 and 3 show that Benson would be willing to pay $5 for

it. So the two people are jointly willing to pay $9 (= $4 + $5) for this unit.

For the second unit of the public good, the collective price they are willing to pay

is $7 (= $3 from Adams plus $4 from Benson); for the third unit they will pay $5

(= $2 plus $3); and so on. By finding the collective willingness to pay for each addi-

tional unit (column 4), we can construct a collective demand schedule (a willing-

ness-to-pay schedule) for the public good. Here, we are not adding the quantities

demanded at each possible price as when we determine the market demand for a

private good. Instead, we are adding the prices that people are willing to pay for the last

unit of the public good at each possible quantity demanded.

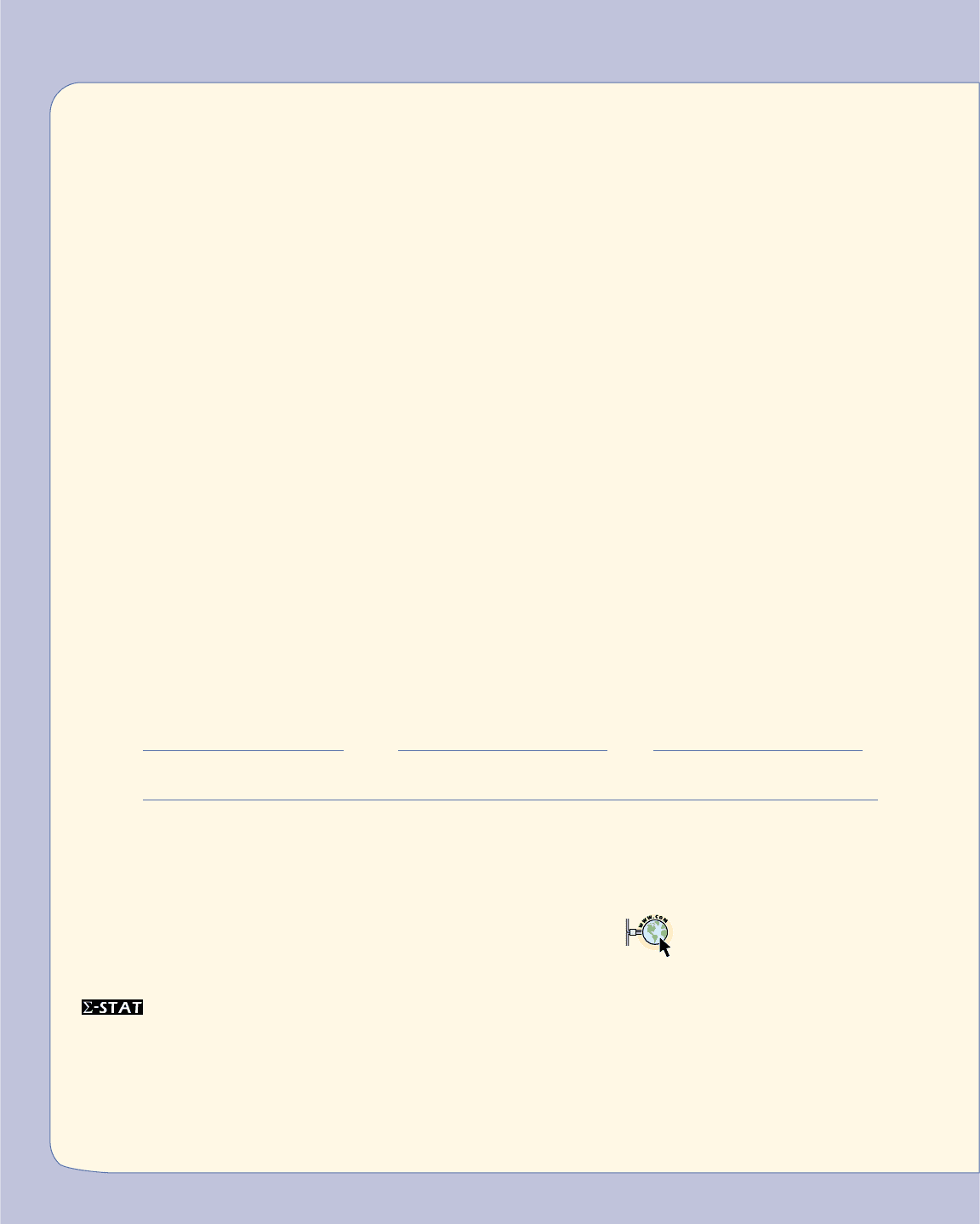

Figure 18-1 shows the same adding procedure graphically, using the data from Table

18-1. Note that we sum Adams’s and Benson’s willingness-to-pay curves vertically to

derive the collective willingness-to-pay curve (demand curve). For example, the height

of the collective demand curve D

c

at two units of output, is $7, the sum of the amounts

that Adams and Benson are each willing to pay for the second unit (= $3 + $4). Likewise,

the height of the collective demand curve at four units of the public good is $3 (= $1 + $2).

What does it mean in Figure 18-1(a) that, for example, Adams is willing to pay $3

for the second unit of the public good? It means that Adams expects to receive $3 of

extra benefit or utility from that unit. And we know from the law of diminishing

marginal utility that successive units of any good yield less and less added benefit.

This is also true for public goods, explaining the downward slope of the willing-

ness-to-pay curves of both Adams and Benson, and of the collective demand curve.

These curves, in essence, are marginal-benefit curves. (Key Question 1)

Supply of Public Goods

The supply curve for any good, private or public, is its marginal-cost curve. Mar-

ginal cost rises as more of a good is produced. The reason is the law of diminishing

returns, which applies whether a society is making missiles (a public good) or

mufflers (a private good). In the short run, government has fixed resources (public

capital) with which to produce public goods such as national defence. As it adds

458 Part Four • Microeconomics of Government and Public Policy

TABLE 18-1 DEMAND FOR A

PUBLIC GOOD,

TWO INDIVIDUALS

(1) (2) (3) (4)

Quantity Adams’s Benson’s Collective

of public willingness willingness willingness

good to pay (price) to pay (price) to pay (price)

1$4+$5=$9

2 3 +4 =7

3 2 +3 =5

4 1 +2 =3

5 0 +1 =1

more units of a variable resource (labour) to these fixed resources, total product

eventually rises at a diminishing rate. That means that marginal product falls and

marginal cost rises, explaining why curve S in Figure 18-1(c) slopes upward.

Optimal Quantity of a Public Good

We can now determine the optimal quantity of the public good. The collective

demand curve D

c

in Figure 18-1(c) measures society’s marginal benefit of each unit

of this particular good. The supply curve S in that figure measures society’s mar-

ginal cost of each unit. The optimal quantity of this public good occurs where mar-

ginal benefit equals marginal cost, or where the two curves intersect. In Figure

18-1(c) that point is three units of the public good, where the collective willingness

to pay for the last (third) unit—the marginal benefit—just matches that unit’s mar-

ginal cost ($5 = $5). As we saw in Chapter 2, equating marginal benefit and marginal

cost efficiently allocates society’s scarce resources. (Key Question 2)

chapter eighteen • government and market failure 459

FIGURE 18-1 THE OPTIMAL AMOUNT OF A PUBLIC GOOD

$9

7

5

3

1

1234

05

P

Q

Optimal quantity

Collective

willingness

to pay

(c) Collective demand and supply

$6

5

4

3

2

1

1234

05

P

Q

Benson's

willingness

to pay

(b) Benson

$6

5

4

3

2

1

1234

05

P

Q

S

D

c

D

2

D

1

Adams's

willingness

to pay

(a) Adams

The collective demand curve for a public good, as shown by

D

c

in panel (c), is found by summing vertically the individual

willingness-to-pay curves D

1

in panel (a) and D

2

in panel (b)

of Adams and Benson, the only two people in the economy.

The supply curve of the public good represented in panel (c)

slopes upward and to the right, reflecting rising marginal

costs. The optimal amount of the public good is three units,

determined by the intersection of D

c

and S. At that output,

marginal benefit (reflected in the collective demand curve

D

c

) equals marginal cost (reflected in the supply curve S).

Cost–Benefit Analysis

The above example suggests a practical means, called cost–benefit analysis, for

deciding whether to provide a particular public good and how much of it to

provide. Like our example, cost–benefit analysis (or marginal benefit–marginal cost

analysis) involves a comparison of marginal costs and marginal benefits.

CONCEPT

Suppose the federal government is contemplating a highway construction plan.

Because the economy’s resources are limited, any decision to use more resources in

the public sector will mean fewer resources for the private sector. There will be both

a cost and a benefit. The cost is the loss of satisfaction resulting from the accompa-

nying decline in the production of private goods; the benefit is the extra satisfaction

resulting from the output of more public goods. Should the needed resources be

shifted from the private to the public sector? The answer is yes if the benefit from

the extra public goods exceeds the cost that results from having fewer private

goods. The answer is no if the cost of the forgone private goods is greater than the

benefit associated with the extra public goods.

Cost–benefit analysis, however, can indicate more than whether a public program

is worth doing. It can also help the government decide on the extent to which a proj-

ect should be pursued. Real economic questions cannot usually be answered sim-

ply by yes or no but, rather, are matters of how much or how little.

ILLUSTRATION

Although a few private toll roads exist, highways clearly have public good charac-

teristics because the benefits are widely diffused and the exclusion principle is not

easily applied. Should the federal government expand the federal highway system?

If so, what is the proper size or scope for the overall project?

Table 18-2 lists a series of increasingly ambitious and increasingly costly highway

projects: widening existing two-lane highways; building new two-lane highways;

building new four-lane highways; building new six-lane highways. The extent to

which government should undertake highway construction depends on the costs

and benefits. The costs are largely the costs of constructing and maintaining the high-

ways; the benefit is an improved flow of people and goods throughout the nation.

The table shows that total benefit (column 4) exceeds total cost (column 2) for

plans A, B, and C, indicating that some highway construction is economically justi-

fiable. We see this directly in column 6, where total costs (column 2) are subtracted

460 Part Four • Microeconomics of Government and Public Policy

TABLE 18-2 COST–BENEFIT ANALYSIS FOR A NATIONAL HIGHWAY

CONSTRUCTION PROJECT, BILLIONS OF DOLLARS

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

Plan Total cost Marginal Total Marginal Net benefit

of project cost benefit benefit or (4) – (2)

No new construction $ 0 $ 0 $0

A: Widen existing highways 4

$4

5

$5

1

B: Two-lane highways 10

6

13

8

3

C: Four-lane highways 18

8

23

10

5

D: Six-lane highways 28

10

26

3

–2

cost–

benefit

analysis

Comparing the

marginal costs of a

government project

or program with the

marginal benefits to

decide whether to

employ resources

in that project or

program and to

what extent.

from total annual benefits (column 4). Net benefits are positive for plans A, B, and

C. Plan D is not economically justifiable because net benefits are negative.

But the question of optimal size or scope for this project remains. Comparing the

additional, or marginal, cost and the additional, or marginal, benefit relating to each

plan determines the answer. The guideline is well known to you from previous dis-

cussions: increase an activity, project, or output as long as the marginal benefit (col-

umn 5) exceeds the marginal cost (column 3). Stop the activity at, or as close as

possible to, the point at which the marginal benefit equals the marginal cost. Do not

undertake a project for which marginal cost exceeds marginal benefit.

In this case plan C (building new four-lane highways) is the best plan. Plans A

and B are too modest; the marginal benefits exceeds the marginal costs. Plan D’s

marginal cost ($10 billion) exceeds the marginal benefit ($3 billion) and therefore

cannot be justified; it overallocates resources to the project. Plan C is closest to the

theoretical optimum because its marginal benefit ($10 billion) still exceeds marginal

cost ($8 billion) but approaches the MB = MC (or MC = MB) ideal.

This marginal cost = marginal benefit rule actually tells us which plan provides

the maximum excess of total benefits over total costs, or in other words, the plan that

provides society with the maximum net benefit. You can confirm directly in column

6 that the maximum net benefit (of $5 billion) is associated with plan C.

Cost–benefit analysis shatters the myth that “economy in government” and

“reduced government spending” are synonymous. “Economy” is concerned with

using scarce resources efficiently. If the cost of a proposed government program

exceeds its benefits, then the proposed public program should not be undertaken,

but if the benefits exceed the cost, then it would be uneconomical or “wasteful” not

to spend on that government program. Economy in government does not mean

minimization of public spending; it means allocating resources between the private

and public sectors to achieve maximum net benefit. (Key Question 3)

In performing its allocation function, government not only produces public goods

but also corrects for kinds of market failure called externalities or spillovers. Recall

from Chapter 4 that a spillover is a cost or a benefit accruing to an individual or

group—a third party—that is external to a market transaction. An example of a

spillover cost or a negative externality is the cost of breathing polluted air; an exam-

ple of a spillover benefit or a positive externality is the benefit of having everyone

else inoculated against some disease. When there are spillover costs, an overpro-

duction of the related product occurs as does an overallocation of resources to this

product. Conversely, underproduction and underallocation of resources result

when spillover benefits are present. We can demonstrate both graphically.

chapter eighteen • government and market failure 461

mc = mb

rule

For a

government project,

marginal benefit

should equal mar-

ginal cost to pro-

duce maximum

benefit to society.

● The demand (marginal–benefit) curve for a pub-

lic good is found by vertically adding the prices

all the members of society are willing to pay for

the last unit of output at various output levels.

● The socially optimal amount of a public good is

the amount at which the marginal cost and mar-

ginal benefit of the good are equal.

● Cost–benefit analysis is the method of evaluat-

ing alternative projects or sizes of projects by

comparing the marginal cost and marginal ben-

efits and applying the MC = MB rule.

Externalities Revisited

externali-

ties

Benefits or

costs from produc-

tion or consumption

accruing without

compensation to

nonbuyers and

nonsellers of the

product.