Odekon M. Encyclopedia of paleoclimatology and ancient environments

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

that hominins existed at least 6 Ma suggests that the divergence

between apes and humans took place earlier, during the late

Miocene, perhaps between 7 and 9 Ma.

The gracile australopithecines were the dominant hominin

group from about 4–2.5 Ma and it is likely that several species

existed at the same time; A. africanus and A. afarensis were

important species. One of the earliest australopithecines, Aus-

tralopithicus anamensis, dated at 4.2 Ma, was found in north-

ern Kenya (Leakey et al., 1995) and the group lived in a

large region stretching from South Africa to Ethiopia. Two

hominin lineages diverged at about 2.5 Ma from the early more

gracile australopithecines, leading to the robust australopithe-

cines (e.g., Paranthropus boisei), who eventually went extinct,

and the earliest members of the genus Homo that led to modern

humans (Figure H12). There is some uncertainty, however,

concerning the age of the earliest Homo. The genus may be

as old as 2.4 Ma, but it was definitely present by 1.9 Ma, when

the lineage had radiated to produce three species: H. habilis,

H. rudolfensis and H. erectus (Wood, 1992). The genus Homo

overlapped in both space and in time with the robust aus-

tralopithecines, but eventually became the single survivor.

Anatomically modern humans, Homo sapiens, are recognized

from about 200,000 years ago.

Evolution of hominin traits

There are two key physical traits that can be tracked in the

hominin fossil record: (a) bipedal locomotion (which appeared

early on and characterizes all hominins), and (b) an increase in

brain capacity relative to body size (associated with genus

Homo). Average cranial capacity ranges from 400 cm

3

in

australopithecines, 650 cm

3

in early Homo to 1,400 cm

3

in modern humans (Homo sapiens). The two characteristics

were assumed to be linked somehow and early models of

human evolution envisioned that hominins would leave the

safety of trees, develop bipedalism, and then the increase in

brain size would follow. However, the fossil evidence suggests

that bipedalism and an increase in brain size were independent.

The fossil evidence of one of the oldest hominins, Orrorin

tugenensis (6 Ma), reveals it was a good tree climber, but it

had already adapted to bipedalism when on the ground (Senut

et al., 2001). A study of A. africanus fossils from South Africa

dated between 2 and 3 Ma showed a bipedal creature that had

a “primitive” body with a more “advanced” cranial capacity

(ranging from 435 to 530 cm

3

) (McHenry and Berger, 1998).

The primitive body consisted of a large chest and long upper

limbs with a small pelvic girdle and short lower limbs. These

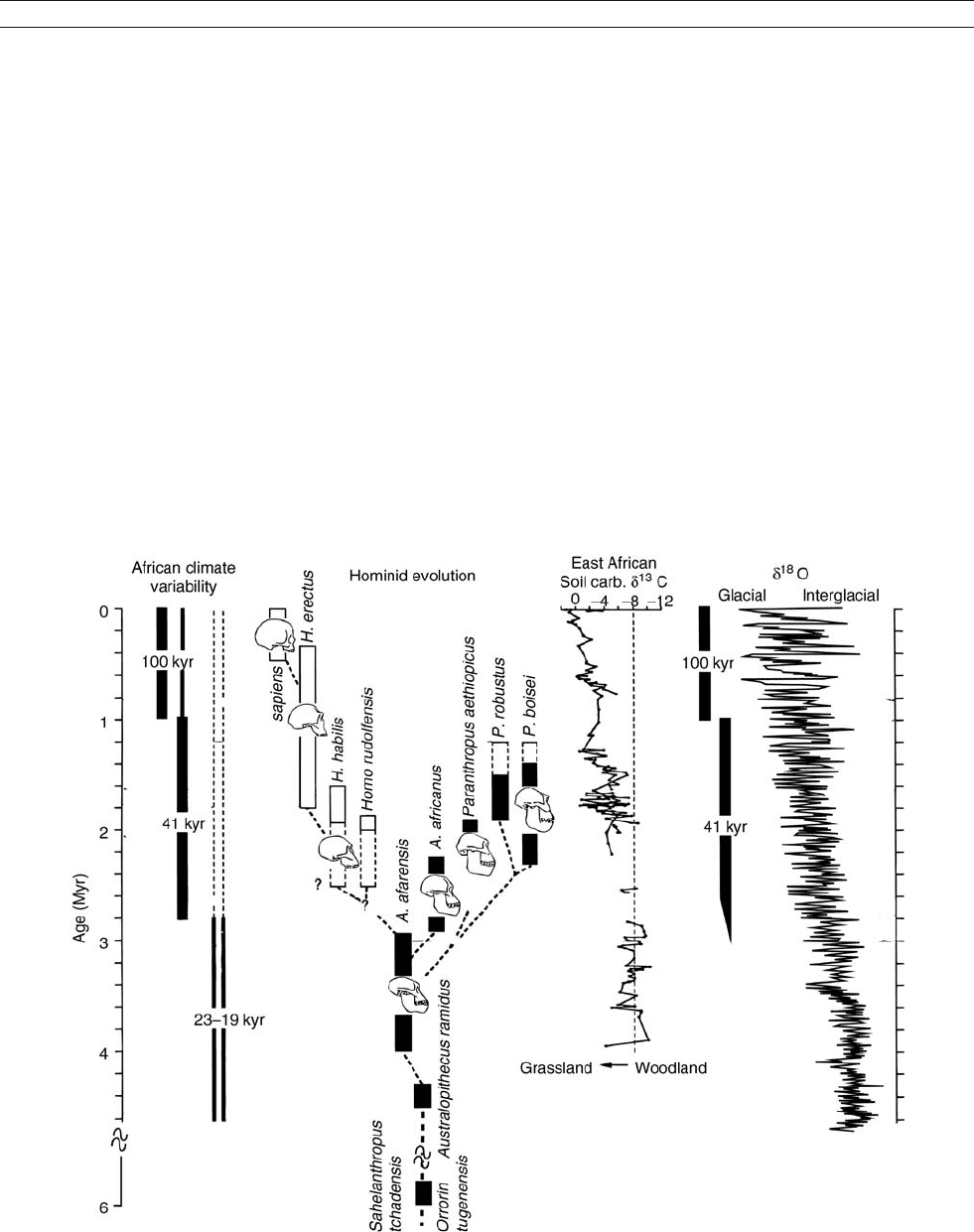

Figure H13 A comparison of the African climate variability represented by the dominance of Milankovitch cycles (far right); a graph of human

phylogeny (Wood, 1992); vegetation record interpreted from the carbon isotopes in soils (Cerling and Hay, 1988; Cerling, 1992); global

temperatures interpreted from oxygen isotopes from the marine record (Shackleton et al., 1990) (modified from deMenocal and Bloemendal, 1995).

448 HUMAN EVOLUTION AND CLIMATE CHANGE

characteristics suggest tree climbing was still important to some

hominins despite the ability to walk on two legs and the pos-

session of a larger brain.

The development of technology, abstract thought, language,

and culture are thought to develop when the brain attains

significant cranial capacity. As body size and sex affects cranial

capacity, a direct correlation is not appropriate. Primitive stone

tool making, the first evidence of technology, dates to 2.5 Ma

(Semaw et al., 1997). These tools are assumed to be a product

of Homo, but there is no direct evidence of this. The human

abilities of language and complex cognitive thought leave no

record, but it appears that these had evolved in hominins

200,000–300,000 years ago, based on dated archaeological

sites containing grindstones, pigments, and stone blades

(McBrearty and Brooks, 2000). By 100,000 years ago, there

are records of long distance exchange, fish hooks, and mining,

and by 50,000 years ago, beads and other art forms are found

(McBrearty and Brooks, 2000).

Global climate change

The Earth’s climate has varied significantly over its 4.6 billion

year history. The climate system, a complex interaction of five

components (oceans, land surface, ice, atmosphere, and vegeta-

tion) is forced by the tectonics, variations in strength of the

Sun, and astronomic forcing, i.e., changes in the Earth’s orbit

(Ruddiman, 2001). The most continuous and complete record

of climate change since the evolution of primates (<65 million

years ago) occurs in marine sediments. Microfossils and miner-

als collected in long sediment cores from ocean basins around

the world are analyzed for variations. Oxygen isotopes in

foraminifers and diatoms (tiny marine organisms) and dust

blown from continental deserts are used as proxies for climate

change over time. The isotope variability reflects global tem-

perature (ice volume) changes, whereas the dust signifies

moisture changes (Hays et al., 1976; deMenocal, 1995). More

fragmentary continental records that occur in lakes or in soils

are used to provide additional climate information. For exam-

ple, carbon isotopes in soil carbonates serve as a proxy for

vegetation change and have been used to determine the propor-

tion of forests, open woodland and savannah (Cerling, 1984;

Cerling et al., 1993).

Both the marine and terrestrial records during the Cenozoic

era (last 65 million years) point to general cooling and

drying that ultimately led to the ice ages of the Pleistocene

epoch (Figure H12). There were times of particularly abrupt

cooling (14 and 2.8 Ma) that brought on increases in global

ice volumes. At 14 Ma, the Antarctic glaciers increased in size

and became permanent; 2.8 Ma marks the onset of Northern

Hemisphere continental-scale glaciation. The general cooling

of the Earth has been linked to plate tectonics that led to mas-

sive uplifts (i.e., mountain building in the Tibetan Plateau and

western North America) and later (10–4 million years) the

closing of the Isthmus of Panama, which changed oceanic cir-

culation (Stanley, 1995; Ruddiman, 2001).

Although the long-term trend has been toward a cooler and

drier climate, the record clearly shows oscillations on a variety

of time scales and more importantly an increase in the magni-

tude of these climate swings, particularly in recent times

(Figure H12). Many have been related to long-term variations

in solar radiation caused by the relative position of the Earth

with respect to the Sun (Milankovitch cycles), as well as

short-term variations (solar radiance). Milankovitch cycles

include 100 ka cycles, which are due to eccentricity of the

Earth’s orbit; 41 ka cycles, reflecting the tilt of the Earth

(obliquity); and 21 ka cycles, related to the precession of

the equinoxes. The ice ages that dominated the Northern Hemi-

sphere in the Pleistocene are related to both the 100 and 41 kyr

Milankovitch cycles (Ruddiman, 2001).

Climate during the last 6 million years, when hominins

evolved into modern humans, has been characterized by high

variability. 6 million years ago, it was cooler and drier, but with

more seasonal continental conditions and the periodic enhance-

ment of the Indian monsoon system (Ruddiman, 2001). Mon-

soon strength is directly related to the 21 ka precession cycle

that changes amount of solar radiation reaching the Earth. Lake

levels rose and fell to the rhythm of this shortest Milankovitch

cycle and wet-dry cycles dominated the tropics where human

evolution took place. This climate variability would have had

a significant impact on hominins and is likely to have been a

key factor in human evolutionary response.

Evolution and climate

It is tempting to begin to make correlations be tween the dra-

matic evolutionary changes of hominins from tree dweller to

modern humans capable of space travel and the climatically

turbulent environment of Africa in which much of this evolu-

tion took place. Speciation events are commonly attributed to

climate change, because without the catalyst of environmen-

tal change, m ost species and ecosystems would remain in

equilibrium and unchanged (Vrba et al., 1995; Poirier and

McKee, 1999). Linking a specific climate circumstance to a

specific evolutionary change is problematic. Some question

whether global climate signatures are felt at the environmen-

tal level important to human survival (Behresmeyer, 1982).

Despite the fact that the hominin fossil record is meager

and widely dispersed and the paleoclimate record, particu-

larly on land, is scanty, there are some generalizations that

can be made.

During the last 5–7 million years, general cooling and dry-

ing in Africa caused a decrease in forest and an increase

in open woodland and savannah grasslands. Coincidentally,

this is the time that hominins began to develop bipedal locomo-

tion, although early fossil evidence indicates they retained

their tree climbing skills for a considerable time. Approxima-

tely 2.5 million years ago, the World’s climate system experi-

enced increasing variability, continental glaciers developed in

the Northern Hemisphere, and the tropics became drier

(Figure H12). Coincidentally, the first appearance of the genus

Homo occurred at about this time along with the first appear-

ance of hominin “technology,” i.e., stone tools. The discovery

of primitive tools and hominins (Homo) in the Republic of

Georgia at 1.75 Ma may record the migration out of Africa to

seek a more stable environment (Gabunia et al., 2000). There

are now indications that other animals in Africa showed an

evolutionary response to the changing environment. In a study

of grazing and browsing fauna in northern Kenya and Ethiopia,

Behresmeyer et al. (1997) found that the cooling and drying

climate gradually nudged the population toward more grass-

land-adapted species.

How does climate change trigger evolution? Climate may act

more like a filter. Potts (1996a, b) proposed an ecological model

termed “variability selection” to explain patterns of hominin

evolution. He suggests that dramatic climate shifts favor animals

that can readily adapt to new environments. He points out the

HUMAN EVOLUTION AND CLIMATE CHANGE 449

trend toward survival of the generalist, rather than the specialist.

Those lineages capable of living in varied environments and

adapting to change succeed. Whereas, those more specialized

go extinct when they fail to adapt to new conditions. Humans

have survived droughts and ice ages and live in every possible

ecological niche from high altitudes (4,500 m) to sea level

and from arctic sea ice to tropical jungles.

Conclusions

Specific climatic events cannot be linked directly to a specific

evolutionary response in the family Hominidae. However, there

is a broad coincidence between aridification of Africa (and the

associated expansion of open woodlands and grasslands) over

the last 7 Ma and the development of bipedalism. Increasing

climate variability at about 2.5 Ma is associated with the first

record of genus Homo, the first appearance of stone tools (evi-

dence of technological capabilities), the increase in cranial

capacity, and eventually the migration of hominins out of

Africa. The development of complex cognitive processes, lan-

guage, art, etc. cannot be tied directly to climate, but may fall

into the “variability selection” theory where dramatic climatic

shifts favor animals that are truly generalists and can adapt to

a wide range of environmental conditions (Potts, 1996a).

Gail M. Ashley

Bibliography

Ashley, G.M., and Hay, R.L., 2002. Sedimentation patterns in a Plio-

Pleistocene volcaniclastic rift-margin basin, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania.

In Renaut, R.W., and Ashley, G.M. (eds.), Sedimentation in Contin-

ental Rifts. (SEPM Special Publication 73) Tulsa, OK: SEPM (Society

for Sedimentary Geology), pp. 107–122.

Behresmeyer, A.K., 1982. The geological context of human evolution.

Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci., 10,39–60.

Behresmeyer, A.K., Todd, N.E., Potts, R., and McBrinn, G.E., 1997. Late

Pliocene faunal turnover in the Turkana Basin, Kenya and Ethiopia.

Science, 278, 1589–1594.

Behrensmeyer, A.K., Potts, R., Deino, A., and Ditchfield, P., 2002. Olorge-

sailie, Kenya: A million years in the life of a rift basin. In Renaut, R.W.,

and Ashley, G.M. (eds.), Sedimentation in Continental Rifts. (SEPM

Special Publication 73) Tulsa, OK: SEPM (Society for Sedimentary

Geology), pp. 97–106.

Boaz, N.T., and Burckle, L.H., 1983. Paleoclimatic framework for African

hominid evolution. In: SASQUA International Symposium Proceedings,

pp. 483–490. Location: Transvaal Museum, Swaziland, Africa; Time:

29 August to 2 September, 1983.

Brain, C., 1981. Hominid evolution and climate change. S. Afr. J. Sci., 77,

104–105.

Bromage, T., and Schrenk, F. (eds.), 1999. African Biogeography, Climate

Change, and Human Evolution. New York: Oxford University Press,

485pp.

Brown, F.H., and Feibel, C.S., 1991. Stratigraphy, depositional environments

and paleogeography of the Koobi Fora Formation. In Harris, J.M. (ed.),

Koobi Fora Research Project, Volume 3. Stratigraphy, artiodactyls and

Paleoenvironments. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, pp. 1–30.

Brunet, M., Guy, F., Pilbean, D. et al., 2002. A new hominid from the

Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa. Nature, 418, 145–151.

Cerling, T.E., 1984. The stable isotopic composition of modern soil carbonate

and its relation to climate. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 71,229–240.

Cerling, T.E., 1992. Development of grasslands and savannas in East

Africa during the Neogene. Palaeogeogr, Palaeoclimatol, Palaeoecol,

97, 241–247.

Cerling, T.E., and Hay, R.L., 1988. An isotopic study of paleosol carbo-

nates from Olduvai Gorge. Quaternary Res., 25,63–78.

Cerling, T.E., Wang, Y., and Quade, J., 1993. Global ecological change in

the late Miocene: Expansion of C

4

ecosystems. Nature, 361, 344–345.

deMenocal, P.B., 1995. Plio-Pleistocene African climate. Science, 270,

53–59.

deMenocal, P.B., and Bloemendal, J., 1995. Plio-Pleistocene climatic varia-

bility in subtropical Africa and the paleoenvironment of hominid evolu-

tion: A combined data-model approach. In Vrba, E.S., Denton, G.H.,

Partridge, T.C., and Burckle, L.H. (eds.), Paleoclimate and Evolution

with Emphasis on Human Origins. New Haven, CT: Yale University

Press, pp. 262–288.

Feibel, C.S., 1997. Debating the environmental factors in hominid evolu-

tion. GSA Today, 7,1–7.

Feibel, C.S., Harris, J.M., and Brown, F.H. 1991. Neogene paleoenviron-

ments of the Turkana Basin. In Harris, J.M. (ed.), Koobi Fora Research

Project, Volume 3. Stratigraphy, artiodactyls and Paleoenvironments.

Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 321–370.

Foley, R.A., 1994. Speciation, extinction and climatic change in hominid

evolution. J. Hum. Evol., 26, 275–289.

Gabunia, L., Vekua, A., Lordkipanidze, D., Swisher, C.C. III, Ferring, R.,

Justus, A., Nioradze, M., Tvsatchretidze, M., Anton, S.C., Bosinski, G.,

Jőris, O., de Lumley, M.A., Majsuradze, G., and Mouskhelishvili, A.,

2000. Earliest Pleistocene hominid cranial remains from Dmanisi,

Republic of Georgia: Taxonomy, geological setting, and age. Science,

288, 1019–1025.

Haile-Selassie, Y., Suwa, G., White, T.D., 2004. Late Miocene teeth from

Middle Awash, Ethiopia, and early hominid dental evolution. Science,

303, 1503–1505.

Hay, R.L., 1976. Geology of the Olduvai Gorge, a Study of Sedimentation

in a Semiarid Basin. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press,

203pp.

Hays, J.D., Imbrie, J., and Shackleton, N.J., 1976. Variations in the earth’s

orbit: Pacemaker of the ice ages. Science, 194, 1121–1131.

Leakey, M.G., Feibel, C.S., McDougall, I., and Walker, A., 1995. New

four-million-year-old hominid species from Kanapoi and Allia Bay,

Kenya. Nature, 376, 565–571.

McBrearty, S., and Brooks, A.S., 2000. The revolution that wasn’t: A new

interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior. J. Hum. Evol.,

39, 453–563.

McHenry, H.M., and Berger, L.R., 1998. Limb proportions in Australo-

pithicus africanus and the origins of the genus Homo. J. Hum. Evol.,

35,1–22.

Partridge, T.C., Bond, G.C., Hartnady, C.J.H., deMenocal, P.B., Ruddiman,

W.F., 1995. Climatic effects of Late Neogene tectonism and volcanism.

In Vrba, E.S., Denton, G.H., Partridge, T.C., and Burckle, L.H. (eds.),

Paleoclimate and Evolution with Emphasis on Human Origins. New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press, pp. 8–23.

Pickford, M., and Senut, B., 2001. The geological and fuanal context of

Late Miocene hominid remains from Lukeino, Kenya. C.R. Academy

Science Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes, Earth Planet. Sci.,

332, 145–152.

Poirier, F.E., and McKee, J.K., 1999. Understanding Human Evolution,

4th edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 386pp.

Potts, R., 1 996a. Evolution and climate variability. Scien ce, 27 3,

922–923.

Potts, R., 1996b. Humanity’s Descent: The consequences of ecological

instability. New York: W. Morrow, 325pp.

Ruddiman W.F., 2001. Earth’s Climate, Past and Future. New York:

W.H. Freeman, 465pp.

Shackleton, N.J., Berger, A., and Peltier, W.R., 1990. An alternative astro-

nomical calibration of the Lower Pleistocene timescale based on ODP

Site 677. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci., 81, 251–261.

Semaw, S., Harris, J.W.K., Feibel, C.S., Renne, P., Bernor, R.L., Fessaha, N.,

and Mowbray, K., 1997. The oldest archaeological sites with an early

Oldowan Industry from the Gona River deposits of Ethiopia. Nature,

385, 333–336.

Senut, B., Pickford, M., Gommery, D., Mein, P., Cheboi, K., and Coppens, Y.

2001. First hominid from the Miocene (Lukeino Formation) Kenya.

C.R. Academy Science Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes. Earth

Planet. Sci., 332, 137–144.

Stanley, S.M., 1995. Climatic forcing and the origin of the

human genus. In Effects of past global change in life. “National

Research Council (U.S.)” Washington, DC: National Academy Press,

pp. 233–243.

Tattersall, I., 1993. The Human Odyssey: Four Million Years of Human

Evolution. New York: Prentice Hall, 191pp.

Vrba, E.S., Denton, G.H., Partridge, T.C., and Burckle, L.H., 1995. Paleo-

climate and Evolution, with Special Emphasis on Human Origins. New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 547pp.

450 HUMAN EVOLUTION AND CLIMATE CHANGE

White, T.D., Suwa, G., and Asfaw, B., 1994. Australopithecus ramidus,a

new species of early hominid from Aramis, Ethiopia. Nature, 371,

306–312.

Wood, B., 1992. Origin and evolution of the genus Homo. Nature, 355,

783–790.

Cross-references

Carbon Isotopes, Stable

Cenozoic Climate Change

Climate Change, Causes

Evolution and Climate Change

Neogene Climates

Oxygen Isotopes

Pleistocene Climates

HYPSITHERMAL

Hypsithermal is derived from the Greek root hypsos, meaning

“high.” In geology, the A.G.I. Glossary states that hypsithermal

is “a term proposed by Deevey and Flint (1957) as a substitute for

climate optimum and thermal maximum” (see also Charlesworth,

1957; Schwarzbach, 1963; Nilsson, 1983), in reference to a warm

period during the early to middle Holocene.

The original concept of a postglacial “climatic optimum”

first emerged in the nineteenth century among paleobotanists

in northern Europe from evidence of hazel nuts and leaves dis-

covered at anomalously high latitudes and later from pollen

analyses (mostly in core samples). Three pollen zones were

recognized as discrete subdivisions of this climatic optimum,

following the original nineteenth century pollen-based plan

of Blytt and Sernander (see Sernander, 1908): boreal (V, VI),

Atlantic (VII) and subboreal (VIII) (now classified internationally

as “biozones”).

The proof of an exceptionally warm phase in the early to

middle Holocene is attributable to L. von Post, the Swedish

“father” of modern pollen analysis. In 1946, he recognized

three post-glacial climatic phases, stage II being warmer

than present. Antevs (1953) named them anathermal (“warm-

ing”), altithermal (“high thermal”), and medithermal (“moder-

ating”). However, the last two are linguistic hybrids and should

be replaced respectively by hypsithermal and katathermal (Nils-

son, 1983). Synonymous terms are altithermal (now obsolete),

megathermal (likewise, see Judson, 1953, p. 59) and xerothermal

(specifically hot, dry climates of the postglacial interval). None

of the above is mentioned in the newest edition of The Holocene

(Roberts, 1998). These terms have mostly been limited to North

American authors and have now largely fallen into disuse.

A distinct climatic negative swing in the mid-hypsithermal

at about 3850

BC (5,000

14

CyBP) was first recognized by Tage

Nilsson in 1935 and attributed by many writers to the recent

immigration of human settlers with associated forest clearing.

However, the same negative swing has subsequently been

established worldwide (e.g., the Rotmoos Neoglacial in the

Alps), even in uninhabited areas, as well as in a negative swing

of eustatic sea level (the “Bahama Low”). Thus, its natural

(non-anthropogenic) forcing is now accepted (Nilsson, 1983).

It marks the AT-2/SB-1 biozone boundary. This negative swing

was marked by a dramatic fall in the elm pollen, the so-called

“ulmus decline,” although after a few centuries it recovered

somewhat and the Greenland ice cores show some warming

trends. Significantly, the negative “spike” is seen also in the

solar modulated (

14

C flux record of tree rings Stuiver’s “S”

type), and must therefore be forced by a major fluctuation in

the Sun’s radiation (Stuiver and Braziunas, 1989).

The chronology of these intervals is confused by the difference

between “absolute” ages (now based on varves, tree rings and ice

cores) and the radiocarbon ages (which require calibration). The

hypsithermal interval is traditionally given as 9,000–2,500

BP

(by radiocarbon, from AD 1950), i.e., boreal to subboreal biozones.

However, the oxygen-isotopic temperature records of the Green-

land ice cores suggest a much younger limit. In Dansgaard et al.

(1971), the “climatic optimum” lasts from only about 8,300–

4,800

BP, thus a span of 3,500 sidereal years. It is therefore practi-

cally limited to the Atlantic biozone (AT-1 and AT-2).

Besides the pollen evidence, there are also clear traces of

the “tree line” (the northern limit of tree growth at the edge

of the treeless tundra, or in mountains at a critical elevation;

Markgraf, 1974). Avery stylized approximation of this boundary

was presented by Firbas (1949), who also showed that it did

not coincide with the effective radiation curve for these latitudes

of Milankovitch. This roughly 10,000 yr lag or “retardation”

factor is also observed in worldwide eustatic sea-level curves

(Fairbridge, 1961, 1983; Lowe and Walker, 1997). Unfortu-

nately, all regional sea-level curves are different because of iso-

static and tectonic variables. Probably the nearest approach

to a “standard” curve is that of Ters (1987) or Fairbanks (1989).

The explanation of retardation lies both in the onset of ice-age

glaciation and in its general retreat. Atmospheric cooling pre-

cedes the glacial advance (and sea-level fall), just as warming

precedes post-glacial melting, although both are associated with

secondary climatic fluctuations (notably the Allerød-Younger

Dryas oscillation).

Climatic fluctuations within the hypsithermal interval

became recognized rather widely in all parts of the world after

the 1950s, following the development of radiocarbon dating.

The incidents of neoglacial advance were seen first in the Alps

(e.g., by Patzelt, 1974), and then extended progressively world-

wide (Denton and Porter, 1970; Denton and Karlén, 1973;

Röthlisberger, 1986). In her comprehensive volume on the Lit-

tle Ice Age, Jean Grove (1988) drew attention to preceding

Holocene cycles of climatic cooling during the alleged hyp-

sithermal, marked in the Alps by the Venediger, Frossnitz (or

Larstig), Rotmoos, Löbben and Goschener advances. In the

more recent Scandinavian papers, even more frequent oscilla-

tions are documented (Karlén et al., 1995).

In North America, the Alaskan glaciers have also been

found to fluctuate more or less synchronously with the

European ones. In the semiarid Southwest, there were major

lake-level fluctuations, but their interpretation has been compli-

cated by seasonality contrasts, notably the incidence of winter

rains during cold cycles, as opposed to summer, monsoonal

rains during warm cycles.

Globally, the fluctuations of the hypsithermal are registered

most dramatically by proxies other than neoglacials and their

associated melt-water lakes. The best dated and most homoge-

nous of these are the

14

C flux measurements from tree rings

(Stuiver and Braziunas, 1989). When standardized and reduced

to 10–20 years means, the results disclose an alternation of

major intervals of more than 100 years duration. Each positive

departure is matched by a negative one of equal dimensions.

These are interpreted as being due to fluctuations in solar

radiation, and thus affect terrestrial climates (Fairbridge and

Sanders, 1987; Charvátová and Střeštik, 1991; Windelius and

HYPSITHERMAL 451

Carlborg, 1995). During the 10,500 year history of the

Holocene, there have been approximately 20 of these major

perturbations.

The amplitudes and lengths of these solar perturbations dis-

play a variance that decreases over the second half of the hyp-

sithermal interval. This decrease is apparent in the glacier

fluctuations, as well as in sea level, in fluvial discharge (reflect-

ing flood/drought alternations), and in other proxies. This

systematic behavior is mainly registered in the Northern Hemi-

sphere proxies and may therefore reflect the gradual decrease in

ecliptic angle that accompanies the Earth/Moon precession

cycle, a major climatic forcing of the Milankovitch parameters.

It is now approaching a minimum contrast between Northern

and Southern Hemispheres.

To summarize, the “hypsithermal” is a semi-formal interval,

defined climatically, in Holocene history, originally taken as

between roughly 9,000–2,500 y

BP (radiocarbon years), but

now restricted to about 8,300–5,000 sidereal y

BP It corres-

ponds to the “Atlantic” biozone, and appears to be related

to the Northern Hemisphere phase of the Milankovitch pre-

cession when high continentality led to warmer summers and

colder winters.

Rhodes W. Fairbridge

Bibliography

Antevs, E., 1953. Geochronology of the deglacial and neothermal ages.

J. Geol., 61, 195–230.

Charlesworth, J.K., 1957. The Quaternary Era (2 vols.). London:

E. Arnold, 1700pp.

Charvátová, I., and Střeštik, J., 1991. Solar variability as a manifestation of

the Sun’s motion. Jour. Atm. Terr. Phys., 53, 1019–1025.

Dansgaard, W., Johnsen, S.J., Clausen, H.G., and Langway, C.C. Jr., 1971.

Climatic record revealed by the Camp Century ice core. In Turekian, K.K.

(ed.), The Late Cenozoic Glacial Ages. New Haven, CT: Yale University

Press, pp. 37–56.

Deevey, E.S., and Flint, R.F., 1957. Postglacial Hypsithermal interval.

Science, 125, 182–185.

Denton, G.H., and Karlén, W., 1973. Holocene climatic variations: Their

pattern and possible cause. Quaternary Res., 3, 155–205.

Denton, G.H., and Porter, S.C., 1970. Neoglaciation. Sci. Am., 222,

101–110.

Fairbanks, R.G., 1989. A 17,000-year glacio-eustatic sea level record:

Influence of glacial melting on the Younger Dryas event and deep-

ocean circulation. Nature, 342, 637–642.

Fairbridge, R.W., 1961. Eustatic changes in sea level. In Ahrens, L.H.

et al., (eds), vol. 4, Physics and Chemistry of the Earth. London:

Pergamon, pp. 99–185.

Fairbridge, R.W., 1983. Isostasy and eustasy. In Smith, D., and Dawson, A.

(eds.), Shorelines and Isostasy. London: Academic Press, pp. 3–25.

Fairbridge, R.W., and Sanders, J.E., 1987. The Sun’s orbit, A.D.

750–2050: Basis for new perspectives on planetary dynamics and

Earth-Moon linkage. In Rampino, M.R. et al., (eds.), Climate-History,

Periodicity, and Predictability. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold,

pp. 446–471 (bibliography, 475–541).

Firbas, F., 1949. Spät- und nacheiszeitliche Waldgeschichte Mitteleuropas

nördlich der Alpen. Jena: Fischer, 480pp.

Grove, J.M., 1988. The Little Ice Age. London: Methuen, 498pp.

Judson, S.S., jr., 1953. Geology of the San Juan site, eastern New Mexico.

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, v. 121

, no.1, 70pp.

Karlén, W., et al., 1995. Climate of northern Sweden during the Holocene.

J. Coastal Res., Special Issue, 17,49–54.

Lowe, J.J., and Walker, M.J.C., 1997. Reconstructing Quaternary Environ-

ments, 2nd (edn.). London: Longman.

Markgraf, V., 1974. Palaeoclimatic evidence derived from timberline fluc-

tuations, 67–83. In Labeyrie, J. (ed.), Les Méthodes quantitatives

d’étude des variations du climat au cours du Pléistocène. Colloques

internat. 219. Paris: C.N.R.S., 317pp.

Nilsson, T., 1983. The Pleistocene. Stuttgart: F. Enke Verlag, 651pp.

Patzelt, G., 1974. Holocene variations of glaciers in the Alps, Paris: Collo-

ques Internationaux du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique

no. 210. Les Méthodes quantitative d’étude des variations du climat

au cours du Pléistocene,51–59.

Roberts, N., 1998. The Holocene: An Environmental History, 2nd (edn.).

Oxford: Blackwell, 316pp.

Röthlisberger, F., 1986. 10,000 Jahre Gletchergeschichte der Erde. Aarau,

Verlag Sauerländer, 416pp.

Schwarzbach, M., 1963. Climates of the Past. London: Van Nostrand, 328

Sernander, R., 1908. On the evidence of postglacial changes of climate

furnished by the peat mosses of northern Europe. Geol. Foren., Förh.

Stöckholm, 30, 465–473.

Stuiver, M., and Braziunas, T.F., 1989. Atmospheric

14

C and century-scale

solar oscillations. Nature, 338, 405–408.

Ters, M., 1987. Variations in Holocene sea level on the French Atlantic

coast and their climatic significance. In Rampino, M.R., Newman, W.S.,

and Sanders, J.E. (eds.), Climate: History, Periodicity and Predictability.

New York: Van Nostrand-Reinhold, pp. 204–237.

Windelius, G., and Carlborg, N., 1995. Solar orbital angular momentum

and some cyclic effects on Earth systems. J. Coastal Res., 17,

383–395 (special issue).

Cross-references

Astronomical Theory of Climate Change

Holocene Climates

Holocene Treeline Fluctuations

Ice cores, Antarctica and Greenland

Palynology

Pollen Analysis

Quaternary Vegetation Distribution

Radiocarbon Dating

Sun-climate Connections

452 HYPSITHERMAL

I

ICE CORES, ANTARCTICA AND GREENLAND

Introduction

Polar ice results from the progressive densification of snow

deposited at the surface of the ice sheet. The transformation

of snow into ice generally occurs within the first 100 meters

and takes from decades to millennia, depending on temperature

and accumulation rate, to be completed. During the first stage

of densification, recrystallization of the snow grains occurs

until the closest dense packing stage is reached at relative den-

sities of about 0.55–0.6, corresponding to the snow-firn transi-

tion. Then plastic deformation becomes the dominant process

and the pores progressively become isolated from the surface

atmosphere. The end product of this huge natural sintering

experiment is ice, an airtight material. Because of the extreme

climatic conditions, the polar ice is generally kept at negative

temperatures well below the freezing point, a marked differ-

ence to the ice of temperate mountain glaciers.

Ice cores are cylinders of ice with a diameter of 10 cm.

They are obtained by drilling through glaciers or ice sheets.

This entry deals with ice cores recovered in the two ice

sheets existing today at the surface of the Earth: in Antarctica

and Greenland. Ice cores from mountain glaciers are handled

in another section (see Ice cores, mountain glaciers). Ice cores

range from shallow (from the surface to 100 m), to intermediate

(down to about 1,000 m) and deep (>1,000 m), and are recov-

ered using specific technologies, including thermal and electro-

mechanical drilling systems. The main purposes of recovering

ice cores in Antarctica or Greenland are to describe the past

changes in atmospheric composition and climate of our planet,

understand the past behavior of the ice sheets and the mechan-

isms controlling ice flow, and ultimately contribute to an

improved understanding of the Earth system.

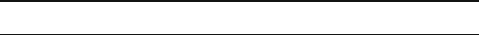

The main Antarctic and Greenland ice cores

Apart from several shallow drilling sites in the most coastal

area and a few drillings through the ice shelves, a total of 14

drill cores have reached bedrock or a depth close to bedrock

in Antarctica and Greenland. Therefore, the current number of

drill sites is still fairly limited in relation to the large dimen-

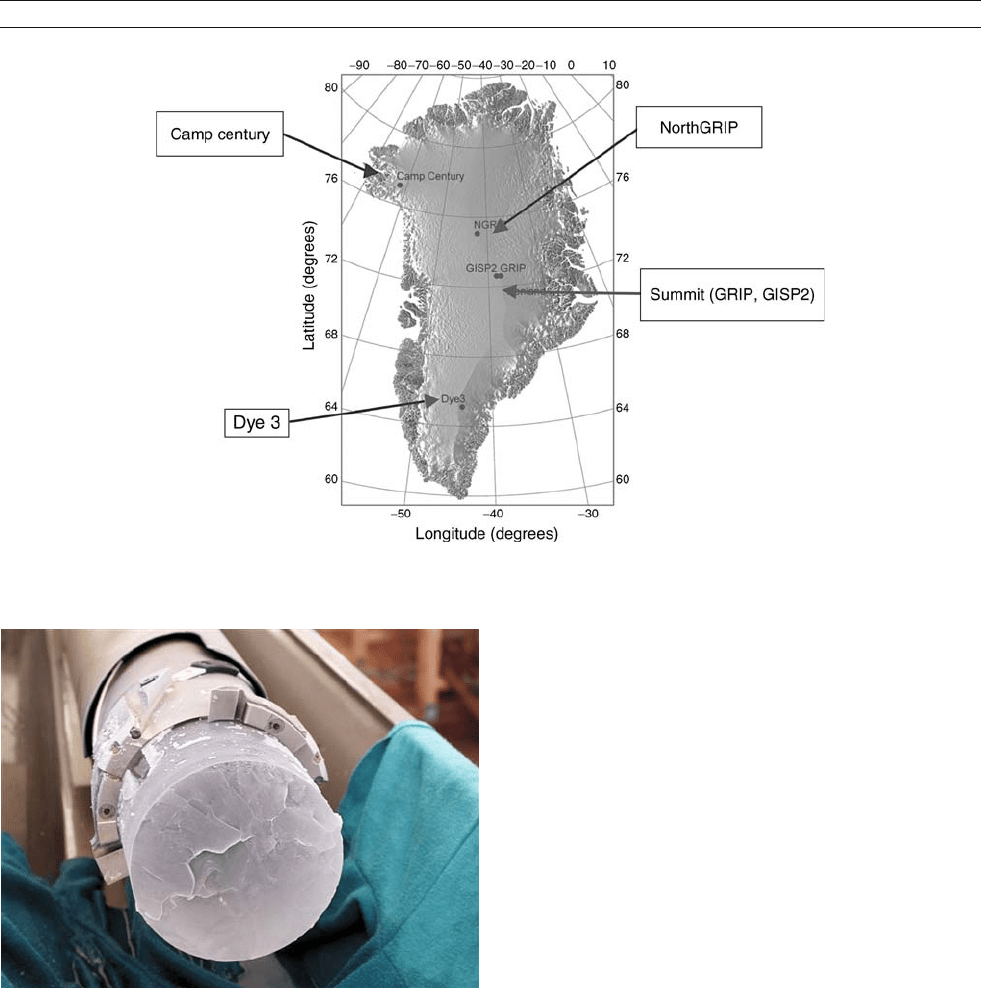

sions of these ice sheets. Table I1 provides information on the

ten deepest drilling operations; Figures I1 and I2 show their

location in Antarctica and Greenland.

Two pioneering long ice cores, the Camp Century (Greenland)

(Hansen and Langway Jr., 1966; Dansgaard et al., 1971)andthe

Byrd (West Antarctica) (Gow et al., 1968; Epstein et al., 1970)

cores, drilled in the 1960s, provided the first continuous and

already detailed record back to the last deglaciation and the last

ice age.

Three deep Antarctic ice cores record several glacial-

interglacial cycles: Vostok (4 cycles, back to 420 ky

BP; Petit

et al., 1999), Dome Fuji (DF) (3 cycles, 330 ky

BP; Watanabe

et al., 2003) and EPICA Dome C (EDC) (8 cycles, 740 ky

BP;

EPICA Community Members, 2004, Figure I3).

The Vostok drill site holds the world’s record in terms of

depth, as of 2007. The EDC core, although shorter by a few

hundred meters, provides the longest record, approximately

twice as old as the Vostok record. New measurements are per-

formed to extend the EDC record back to 800,000 y

BP. Further-

more, a new deep drilling at DF, completed in 2006, lies close

to bedrock. It should provide the second longest record, cover-

ing 700,000 years.

Three long Greenland ice cores, GRIP, GISP2 and NGRIP

coverthelast100,000years;i.e.,mostofthelastglacial-interglacial

cycle, but only the NGRIP core provides an undisturbed record

back to the latest part of the penultimate interglacial (also

called Eemian) (North Greenland Ice Core Project Members,

2004). A new drilling operation (called NEEM) is planned in

Greenland to recover an ice core able to provide a complete

record of the Eemian. In addition, a number of intermediate-type

cores recovered from both ice sheets sample the Holocene

(our current interglacial) and part of the last glacial period with

good resolution.

Establishing an ice core chronology

Establishing the chronology of Antarctic and Greenland ice

cores is essential for interpreting ice core records. The age

of the ice corresponds to the time the snow is deposited at

the surface of the ice sheet and its chronology can be estab-

lished using different tools including layer counting, synchroni-

zation to the Earth orbital variations (orbital tuning approach),

synchronization to other well dated archives, and glaciological

modeling. On the other hand, during snow densification, inter-

stitial air can exchange with the atmosphere at the surface

through the firn porosity until it is trapped in the form of bub-

bles. Therefore, in any ice core, contemporaneous gas and ice

signals are not recorded at the same depth and air occluded in

air bubbles is younger than its surrounding ice.

Note that methods based on radioactive decay are not of use

to date polar ice directly. In particular,

14

C dating of the CO

2

trapped in air bubbles is possible but limited in accuracy

because of in situ production in the firn.

Counting preserved annual layers through the seasonal var-

iations of different properties, like ice isotopic composition,

aerosol chemical composition or dust content, works in sites

with high accumulation rates and is especially appropriate for

Greenland ice cores. For instance, the method has been used

on the DYE-3, GRIP, GISP2 and NGRIP cores, and can be

especially accurate for Holocene ice (maximum counting error

estimated to be up to 2%; Rasmussen et al., 2006). This layer

counting method is, however, not applicable for low accumula-

tion sites such as those of the East Antarctic Plateau. Orbital

variations of the Earth impact the solar radiation received at

the top of the atmosphere (generally called insolation), and in

turn the Earth’s climate. The orbital tuning approach consists of

tuning ice core climatic records to those changes in insolation

that can be accurately calculated for the past millions of years

(Berger, 1978; Laskar et al., 2004). This approach has been

used in the case of the long, 420-kyr Vostok record. Unfortu-

nately, the phasing between insolation and the climatic

response is generally poorly constrained and not likely to be

constant due to the non-linearity of the climatic system, which

is a major limitation of the orbital tuning approach. As a conse-

quence, the chronological uncertainty of the orbital tuning

approaches is about 5 kyr. Nevertheless, it has been recently

suggested that ice core properties recording local insolation

directly may overcome this limitation (Bender, 2002; Raynaud

et al., 2007).

Table I1 Major ice cores: sites, depth, length of record. Please, note that in most cases, we use the first publication that provides the basic

information, rather than the most recent or most relevant ones

Site Ice sheet Year of recovery Depth (m) Temporal length of the record

Camp Century (Dansgaard et al., 1971) Greenland 1966 1,387.4 Back to the last ice age

Byrd (Epstein et al., 1970; Gow et al., 1968) West Antarctica 1968 2,164 Back to the last ice age

Dye 3 (Dansgaard et al., 1985) Greenland 1981 2,037 Back to the last ice age

GRIP (GREENLAND-SUMMIT-ICE-CORES, 1997) Greenland 1992 3,029 105 ka

GISP 2 (GREENLAND-SUMMIT-ICE-CORES, 1997) Greenland 1993 3,053 105 ka

Vostok (Petit et al., 1999) East Antarctica 1998 3,623 420 ka

North GRIP (NORTH-GREENLAND-ICE-CORE-

PROJECT-MEMBERS, 2004)

Greenland 2003 3,085 120 ka

EPICA DC (EPICA-COMMUNITY-MEMBERS, 2004) East Antarctica 2004 3,270 800 ka

EPICA DML (EPICA-COMMUNITY-MEMBERS,

2006)

East Antarctica 2006 2,774 More than one glacial-interglacial

cycle

Dome Fuji East Antarctica 2006 3,029 The age at the bottom is

estimated to be 700 ka

Figure I1 Index map showing the locations of ice cores from Antarctica that are listed in Table I1.

454 ICE CORES, ANTARCTICA AND GREENLAND

Ice cores can also be dated by synchronization with other

well-dated archives. For example, back to the last glacial per-

iod, ice cores from Antarctica can be synchronized with the

Greenland ice cores using the CH

4

records or the Be-10 records

(Yiou et al., 1997; Blunier and Brook, 2001). A second exam-

ple is the identification of well-dated volcanic eruptions in the

ice cores.

In order to provide a method independent of the orbital tun-

ing approach, glaciologists have proposed to date ice cores

continuously using snow accumulation and ice flow models

for calculating the annual layer thickness at each depth. In this

case the main limitations include the uncertainties in our

knowledge of past accumulation changes, basal conditions

(melting, sliding) and rheological conditions.

Finally, it has been recently proposed to use an inverse

method, which associates the information of the different dat-

ing methods available on one core to obtain an optimal chron-

ology . This inverse method has been applied on the Vostok

(Parrenin et al., 2001;Parreninetal.,2004), Dome Fuji (Watanabe

et al., 2003) and EPICA Dome C (EPICA Community Mem-

bers, 2004) cores. In the future, such an inverse method could

be applied to several drilling sites simultaneously, obtaining a

common and optimal chronology for those drilling sites.

The difference between the ages of gas bubbles and the sur-

rounding ice can be computed with a firn model (see Goujon

et al., 2003 and references therein). Under present-day condi-

tions, this difference is on the order of a few centuries for high

accumulation/high temperature sites and of several thousands

of years in sites of the high Antarctic Plateau with low accumu-

lation and temperature conditions (e.g., 3,000 years at Vostok).

Under glacial conditions it increases significantly due to colder

climate, which is paralleled by lower accumulation rates, but

the accuracy of the calculation under past conditions is limited

due to uncertainty in past accumulation rates and temperatures.

Antarctic and Greenland ice core: an archive of the

atmospheric composition and climate

The Antarctic and Greenland ice cores contain a wide spectrum

of information on past changes in the environmental conditions

of the Earth. Examples are given in Table I2.

Polar ice cores record both variations in climate and in

atmospheric composition. They essentially provide a pure

record of solid precipitation, atmospheric gases, dust and aero-

sols and are, in fact, a unique archive of past changes of our

atmosphere. For their part, deep oceanic and continental sedi-

ments are recording oceanic, vegetation or soil changes.

Figure I2 Index map showing the locations of ice cores from Greenland that are listed in Table I1.

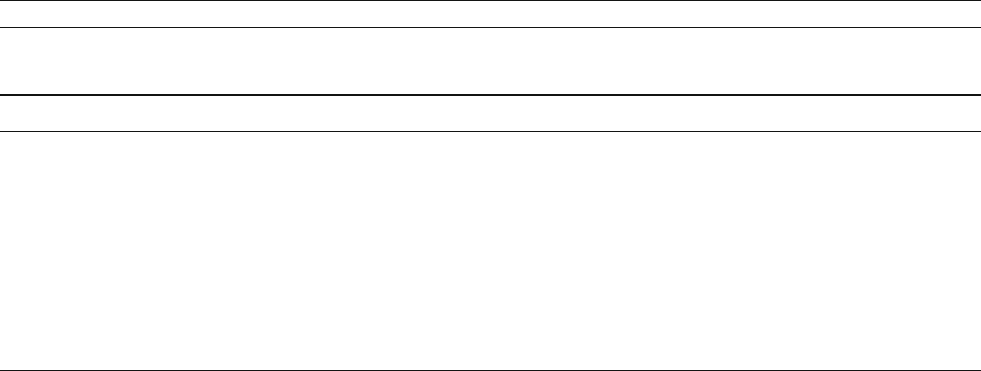

Figure I3 Ice core protruding from the drill head from EPICA Dome C,

Antarctica (photo courtesy of Eric LeFe

`

bre, LGGE, Grenoble).

ICE CORES, ANTARCTICA AND GREENLAND 455

Continuous changes in temperature at the surface of the ice

sheet are revealed by measuring the isotopic composition of the

ice (deuterium or oxygen-18), and more sporadic abrupt tem-

perature changes are accurately recorded by the isotopic com-

position of N

2

and Ar found in the air trapped in ice.

Polar ice cores also provide the most reliable paleo-archive

of air composition, by directly recording atmospheric composi-

tion in the form of air bubbles when the firn becomes ice.

They allow the reconstruction of the past evolution of impor-

tant greenhouse gases (see section on carbon dioxide and

methane, Quaternary variations). Thus, the Vostok and the

new EPICA DC record produce clear evidence of the strong

correlation between greenhouse gases (CO

2

and CH

4

) and

climate over glacial-interglacial cycles (EPICA Community

Members, 2006; see also Carbon dioxide and methane,

Quaternary variations).

Dust and aerosols found in Antarctic or Greenland ice cores

have been collected at the surface of the ice sheets by dry or

wet deposition. The ice record of their concentration and size

distribution provides information about past extent of marine

and continental sources as well as variations in atmospheric

transport. Since marine sources can be influenced by the extent

of sea ice, it may also be able to reconstruct past changes in sea

ice. Ice cores also provide a precious volcanic record in the

same way.

Apart from these natural variations in gases, dust and aero-

sols, ice cores record the impact of human activities, especially

on greenhouse trace gases and sulfate compounds. They also

document paleometallurgy activities from as early as Greek

and Roman times and, during the last few decades, radioactive

fallout and added lead in gasoline.

The ice core record also contains information about past

changes of the ice sheets. The air content of polar ice depends

on the atmospheric pressure when bubbles close-off, and thus

gives information about past surface elevation. Physical proper-

ties of ice such as grain size and orientation are indicators of

past ice flow in the vicinity of the drilling site.

Conclusion

Polar ice cores provide a wide range of information on the Earth

system, some of which have a real impact on societal and educa-

tional issues. Because they play a central role in global change

research, the international ice coring community is planning new

projects in both Antarctica and Greenland under the International

Partnerships in Ice Core Sciences (IPICS) initiative (Brook and

Wolff, 2006). IPICS aims to extend the ice core record in time

and enhance spatial resolution. Concerning deep ice coring, one

of the projects is to search for a 1.5 million year record of climate

and greenhouse gases in Antarctica, during a time period when

Earth’s climate shifted from 40,000 year to 100,000 year

cycles. In northwest Greenland, a deep ice core is planned to

recover a complete record of the Eemian for the first time.

Dominique Raynaud and Frédéric Parrenin

Bibliography

Bender, M., 2002. Orbital tuning chronology for the Vostok climate record

supported by trapped gas composition. Earth Planetary Sci. Lett., 204,

275–289.

Berger, A.L., 1978. Long-term variations of daily insolation and Quatern-

ary climatic changes. J. Atmos. Sci., 35, 2362–2367.

Blunier, T., and Brook, E.J., 2001. Timing of millennial-scale climate

change in Antarctica and Greenland during the last glacial period.

Science, 291, 109–112.

Brook, E., and Wolff, E.W., 2006. The future of ice core science. Eos

Trans. AGU, 87(4), 39.

Dansgaard, W., Johnsen, S.J., Clausen, H.B., and Langway Jr., C.C. 1971.

Climatic record revealed by the camp century ice core. In Turekian,

K.K. (ed.), The Late Cenozoic Glacial Ages. New Haven, London: Yale

University Press, pp. 37–56.

Dansgaard, W., Clausen, H.B., Gundestrup, N., Johnsen, S.J., and Rygner,

C., 1985. Dating and climatic interpretation of two deep Greenland ice

cores. In Langway Jr., C.C., Oeschger, H., and Dansgaard, W. (eds.),

Greenland Ice Core: Geophysics, Geochemistry and the Environment.

Washington, DC: Geophysical Monograph. American Geophysical

Union.

EPICA Community Members, 2004. Eight glacial cycles from an Antarctic

ice core. Nature, 429(6992), 623–628.

EPICA Community Members, 2006. One-to-one coupling of glacial climate

variability in Greenland and Antarctica. Nature 444(7116), 195–198.

Epstein, S., Sharp, R.P., and Gow, A.J., 1970. Antarctic ice sheet: stable

isotope analyses of Byrd station cores and interhemispheric climatic

implications. Science 168, 1570–1572.

Goujon, C., Barnola, J.-M., and Ritz, C., 2003. Modeling the densification

of polar firn including heat diffusion: Application to close-off character-

istics and gas isotopic fractionation for Antarctica and Greenland sites.

J. Geophys. Res., 108. doi:10.1029/ 2002JD003319.

Gow, A.J., Ueda, H.T., and Garfield, D.E., 1968. Antarctic ice sheet: Preli-

minary results of first core hole to bedrock. Science 161, 1011–1013.

Greenland Summit Ice Cores, 1997. J. Geophys. Res., 102(C12),

26315–26886.

Hansen, B.L., and Langway Jr., C.C., 1966. Deep core drilling in ice and

core analysis at camp century, Greenland, 1961–1966. Antarctic J.

US, 1, 207–208.

Table I2 Climatic or environmental parameters and corresponding properties measured in ice. Note the diversity of the information contained in

ice cores, which deals with the atmosphere, the cryosphere, the oceans and the continents

Climatic and environmental parameter Ice properties

Temperature change at the surface of the ice sheet Isotopic composition of the ice (

18

O/

16

O, D /H); Isotopic

composition of the air trapped in ice (

15

N,

40

Ar)

Variations of atmospheric greenhouse trace gases Greenhouse trace gas concentrations in the air trapped in ice

(CO

2

,CH

4

,N

2

O)

Origin of the precipitation Deuterium excess of ice

Atmospheric transport and circulation; Source (marine, continental, volcanic,

anthropogenic) of dust and aerosols

Dust and aerosols in ice

Changes in continental ice volume and sea level; Changes in hydrological

cycle and biological activity

Isotopic composition (

18

O/

16

O) of the atmospheric oxygen trapped

in ice

Local insolation changes due to orbital cycles O2/ N2 of air trapped in ice; Air content of ice

Changes in surface elevation of the ice sheet Air content of ice; Isotopic composition of ice

Changes in ice flow Physical properties of ice

Solar activity and Earth’s magnetic field intensity Beryllium-10 (

10

Be)

456 ICE CORES, ANTARCTICA AND GREENLAND

Laskar, J., Robutel, P., Joutel, F., Gastineau, M., Correira, A.C.M., and

Levrard, B., 2004. A long-term numerical solution for the insolation

quantities of the Earth. Astron Astrophys 428, 261–285.

North Greenland Ice Core Project Members, 2004. High-resolution record

of Northern hemisphere climate extending into the last interglacial

period. Nature, 431, 147–151.

Parrenin, F., Jouzel, J., Waelbroeck, C., Ritz, C., and Barnola, J.-M., 2001.

Dating the Vostok ice core by an inverse method. J. Geophys. Res., 106

(D23), 31837–31851.

Parrenin, F., Rémy, F., Ritz, C., Siegert, M.J., and Jouzel, J., 2004. New

modeling of the Vostok ice flow line and implication for the glaciologi-

cal chronology of the Vostok ice core. J. Geophys. Res., 109.

doi:10.1029/ 2004JD004561.

Petit, J.R., Jouzel, J., Raynaud, D., Barkov, N.I., Barnola, J.-M., Basile, I.,

Bender, M., Chappellaz, J., Davis, M., Delaygue, G., Delmotte, M.,

Kotlyakov, V.M., Legrand, M., Lipenkov, V.Y., Lorius, C., Pépin, L.,

Ritz, C., Saltzman, E., and Stievenard, M., 1999. Climate and atmo-

spheric history of the past 420,000 years from the Vostok ice core,

Antarctica. Nature, 399, 429–436.

Rasmussen, S.O., Andersen, K.K., Svensson, A.M., Steffensen, J.P.,

Vinther, B.M., Clausen, H.B., Siggaard-Andersen, M.-L., Johnsen, S.

J., Larsen, L.B., Dahl-Jensen, D., Bigler, M., Rothlisberger, R., Fischer,

H., Goto-Azuma, K., Hansson, M.E., and Ruth, U., 2006. A new

Greenland ice core chronology for the last glacial termination. J. Geo-

phys. Res., 111, D06102. doi:10.1029/2005JD006079.

Raynaud, D., Lipenkov, V., Lemieux-Dudon, B., Loutre, M-F., Lhomme, N.,

2007. The local insolation signature of air content in Antarctic ice: A new

step toward an absolute dating of ice records. Earth and Planetory

Science Letters, 261, 337–349.

Watanabe, O., Jouzel, J., Johnsen, S., Parrenin, F., Shoji, H., and Yoshida,

N., 2003. Homogeneous climate variability across East Antarctica over

the past three glacial cycles. Nature, 422, 509–512.

Yiou, F., Raisbeck, G.M., Baumgartner, S., Beer, J., Hammer, C.,

Johnsen, J., Jouzel, J., Kubik, P.W., Lestringuez, J., Stievenard, M.,

Suter, M., and Yiou, P., 1997. Beryllium 10 in the Greenland ice core

project ice core at summit, Greenland. J. Geophys. Res., 102,

26783–26794.

Cross-references

Beryllium-10

Carbon Dioxide and Methane, Quaternary Variations

Deuterium, Deuterium Excess

Dust Transport, Quaternary

Ice Cores, Mountain Glaciers

Oxygen Isotopes

Quaternary Climate Transitions and Cycles

SPECMAP

ICE CORES, MOUNTAIN GLACIERS

Introduction

With the help of recent innovations in light-weight drilling

technology, ice core paleoclimatic research has been expanded

from the polar regions to ice fields in many of the world’s

mountain ranges and on some of the world’s highest moun-

tains. Over the last few decades, much effort has been focused

on the retrieval of cores from sub-polar regions such as western

Canada and eastern Alaska, the mid-latitudes such as the

Rocky Mountains and the Alps, and tropical mountains in

Africa, South America, and China. Unlike polar ice cores, cli-

mate records from lower-latitude alpine glaciers and ice caps

present information necessary to study processes where human

activities are concentrated, especially in the tropics and subtro-

pics where 70% of the world’s population lives. During the

last 100 years, there has been an unprecedented acceleration

in global and regional-scale climatic and environmental

changes affecting humanity. The following is an overview of

alpine glacier archives of past changes on millennial to decadal

time scales. Also included is a review of the recent, global-

scale retreat of these alpine glaciers under present climate con-

ditions, and a discussion of the significance of this retreat with

respect to the longer-term perspective, which can only be pro-

vided by the ice core paleoclimate records.

Locations of mountain ice core retrieval

The sites from which many of the high-altitude ice cores have

been retrieved are shown in Table I3. Among the earliest efforts

to retrieve climate records from mountain glaciers were pro-

grams involving surface sampling on the Quelccaya Ice

Cap (13

56

0

S, 70

50

0

W; 5,670 m a.s.l.) in southern Peru

(1974–1979). The results from this preliminary research, con-

ducted by the Institute of Polar Studies (now the Byrd Polar

Research Center) at The Ohio State University, paved the

way for the first high-altitude tropical deep-drilling program

on Quelccaya in 1983, which yielded a 1,500-year climate

record. Meanwhile, in western Canada, a 103-m ice core was

drilled on Mt. Logan (60

35

0

N, 140

35

0

W; 5,340 m a.s.l.) by

Canada’s National Hydrology Research Laboratory. The record

from this core extends back to 1736

AD. Recently, the ice caps

on both these mountains have been redrilled, Mt. Logan in

2002 and Quelccaya in 2003. During the intervening decades,

mountain ice core research has expanded significantly through-

out the world, with programs successfully completed on the

Tibetan Plateau and the Himalayas, the Cordillera Blanca of

Northern Peru, Bolivia, East Africa, the Swiss and Italian Alps,

Alaska, and the Northwest United States (Table I3).

Climatic and environmental information from

mountain ice cores

The records contained within the Earth’s alpine ice caps and

glaciers provide a wealth of data that contribute to a spectrum

of critical scientific questions. These range from the reconstruc-

tion of high-resolution climate histories to help explore the

oscillatory nature of the climate system, to the timing, duration,

and severity of abrupt climate events, and the relative magni-

tude of twentieth century global climate change and its impact

on the cryosphere. Much of the variety of measurements made

on polar ice cores, and the resulting information, is also rele-

vant to cores from mountain glaciers. Researchers can utilize

an ever-expanding ice core database of multiple proxy informa-

tion (i.e., stable isotopes, insoluble dust, major and minor ion

chemistry, precipitation reconstruction) that spans the globe in

spatial coverage and is of the highest possible temporal resolu-

tion. The parameters that can be measured in an ice core are

numerous and can yield information on regional histories of

variations in temperature, precipitation, moisture source, arid-

ity, vegetation changes, volcanic activity and anthropogenic

input (Figure I4). Many of these physical and chemical consti-

tuents produce wet and dry/cold and warm seasonal signals in

the ice, which allow the years to be counted back similar to the

counting of tree rings.

Isotopic ratios of oxygen and hydrogen (d

18

O and dD,

respectively) are among the most widespread and important

of the measurements made on ice cores. Early work on polar

ice cores on these “stable” (i.e., as opposed to unstable, or

radioactive) isotopes indicated that they provide information

on the precipitation temperature (Dansgaard, 1961), based on

ICE CORES, MOUNTAIN GLACIERS 457