Orton C., Tyers P., Vince A. Pottery in archaeology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

210 Assemblages and sites

In our view, it is in most cases extremely difficult to make a quantitative

study of sherd-links. Any such study would depend on being reasonably

certain that one had found all (or almost all) the links on a site. The resources

needed to do this for any but the smallest site would be enormous, in terms of

both time and space, and even the most enthusiastic advocates admit that 'It

will rarely be possible to assign every sherd in a group or deposit to a vessel,

and in some groups there may be many sherds left over' (Moorhouse 1986,

88). This being so, it seems we are dealing with a qualitative and rather

subjective form of evidence which is extremely difficult to interpret except

either: (i) on atypical sites (for example Devils Ditch, p. 179); or (ii) in the

most general terms (see below).

We can look at the problem in two parts. Firstly there is the question of

what the sherd-links actually represent in different circumstances and

secondly there are the practical questions of recognising the links and

presenting the data in such a manner that they can be used by others.

What causes sherd-links?

In some cases sherd-links between contexts are simply the result of the

context having been excavated and recorded in more than one section. It may

be that the same context runs across more than one excavated area and has

different numbers in each, or for some other reason it was excavated in blocks

or areas. Links of this type should be expected and should be eliminated

before proceeding with sherd-links between stratigraphic units.

Otherwise, sherd-links probably fall into three groups. The first is where a

series of sherd-links between contexts indicate that they result from a

sequence of closely spaced actions, the second is where material from existing

levels is disturbed and re-deposited higher up in the stratigraphy, and the

third is where parts of the same vessel have a genuinely different history, some

parts surviving longer in use than others after breakage.

A series of tip lines in a pit may be excavated and recorded separately but

may only represent a sequence of closely spaced actions, such as shovelling a

rubbish accumulation into a pit. A series of sherd-links between such contexts

would be expected and these too should be accounted for before proceeding

with further work. The identification of sherd-links may be used as an aid in

the interpretation of the sequence on a site. They may be used to demonstrate

the possibility or otherwise that certain contexts are open at the same time, or

may help to explain a sequence of dumping and levelling actions. An example

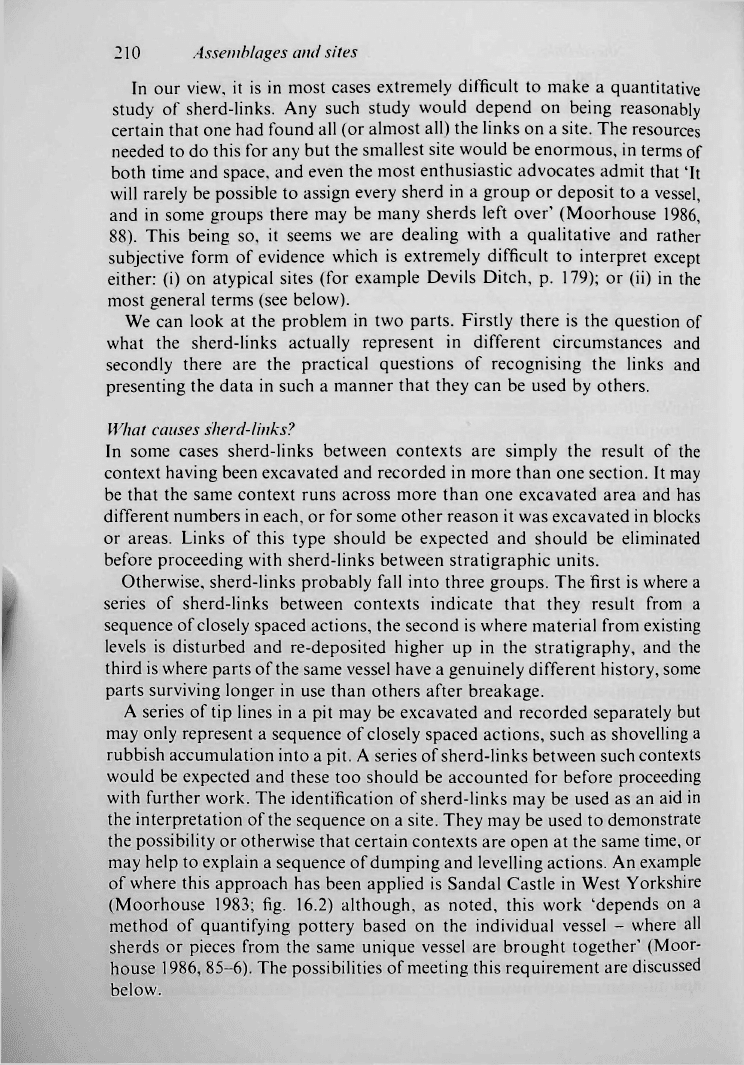

of where this approach has been applied is Sandal Castle in West Yorkshire

(Moorhouse 1983; fig. 16.2) although, as noted, this work 'depends on a

method of quantifying pottery based on the individual vessel - where all

sherds or pieces from the same unique vessel are brought together' (Moor-

house 1986, 85-6). The possibilities of meeting this requirement are discussed

below.

Sherd-links

211

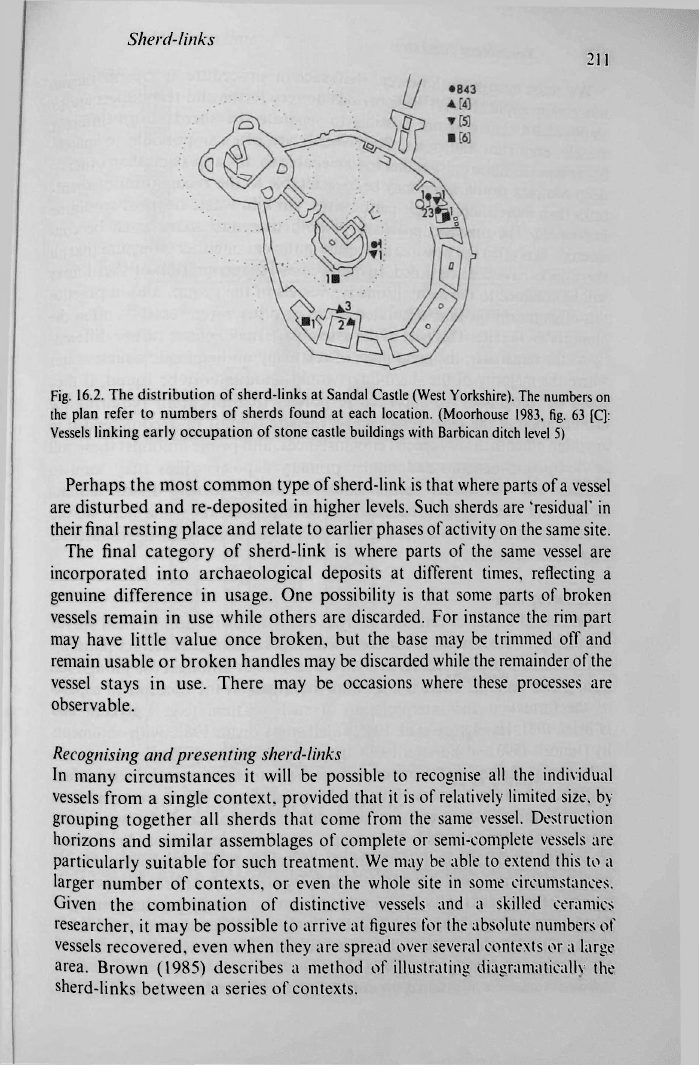

Fig. 16.2. The distribution of sherd-links at Sandal Castle (West Yorkshire). The numbers on

the plan refer to numbers of sherds found at each location. (Moorhouse 1983, fig. 63 [CJ:

Vessels linking early occupation of stone castle buildings with Barbican ditch level 5)

Perhaps the most common type of sherd-link is that where parts of a vessel

are disturbed and re-deposited in higher levels. Such sherds are 'residual' in

their final resting place and relate to earlier phases of activity on the same site.

The final category of sherd-link is where parts of the same vessel are

incorporated into archaeological deposits at different times, reflecting a

genuine difference in usage. One possibility is that some parts of broken

vessels remain in use while others are discarded. For instance the rim part

may have little value once broken, but the base may be trimmed off and

remain usable or broken handles may be discarded while the remainder of the

vessel stays in use. There may be occasions where these processes are

observable.

Recognising and presenting sherd-links

In many circumstances it will be possible to recognise all the individual

vessels from a single context, provided that it is of relatively limited size, by

grouping together all sherds that come from the same vessel. Destruction

horizons and similar assemblages of complete or semi-complete vessels are

particularly suitable for such treatment. We may be able to extend this to a

larger number of contexts, or even the whole site in some circumstances.

Given the combination of distinctive vessels and a skilled ceramics

researcher, it may be possible to arrive at figures for the absolute numbers of

vessels recovered, even when they are spread over several contexts or a large

area. Brown (1985) describes a method of illustrating diagramaticallv the

sherd-links between a series of contexts.

212 Assemblages and sites

We must recognise, however, that such a procedure is by no means

universally applicable. At some periods pottery forms and techniques are so

standardised that it is not possible to separate the sherds from different

vessels, even rims and bases. Body sherds are often impossible to match.

Some types of site are also rather less amenable to this approach than others -

deep complex stratification may be less suitable to the recognition of sherd-

links than more simple single-period sites. On kiln waste heaps it would be

impossible. The practical problems of both time and space must be con-

sidered - it is often not possible to acquire sufficient of either to ensure that all

sherd-links have been recorded. In many cases the recognition of sherd-links

will be confined to the more distinctive vessels in the group, and in practice

this often means the finer decorated wares or other rarer vessels - often the

'imports' to the site. This part of the assemblage may behave rather differen-

tly to the remainder, the great mass of relatively undiagnostic coarse wares

where the majority of the sherd-links would undoubtedly be found, if they

could be recognised. An approach to pottery quantification requiring the

identification of the same vessel across the site cannot be recommended in

anything other than very special circumstances, and prime amongst these will

be destruction horizons and similar primary deposits. This may seem to

conflict with our earlier recommendation about sorting sherd families

(p. 56). But there we only needed links within contexts while here we are

talking about links between contexts, which requires far greater resources if

they are to be found.

Field survey data

A specialised aspect of ceramics analysis is the investigation of field survey

assemblages - also known as surface assemblages or surface artefact patterns.

This material is usually recovered from the surface or amongst the plough soil

during field walking. There is a growing literature on the theoretical aspects

of the formation and interpretation of such scatters (e.g. Lewarch and

O'Brien 1981; Haselgrove et al. 1985; Odell and Cowan 1987, with comments

by Dunnell 1990 and Yorston 1990) and many useful case studies.

It is clear that many factors contribute both to the formation of surface

scatters, and to the recovery of material from surfaces. When we turn to the

variables affecting recovery, the character of the soil and the vegetation

cover, which may be stubble from crops, are clearly important. Brighter or

more distinctively coloured sherds are more likely to be recovered than sherds

whose colour resembles that of the underlying soil, and different individuals

may be better at data collection, resulting in an apparently greater density of

sherds, or may preferentially collect sherds of different types (perhaps

skewing the date distribution of the assemblage). These and other variations

are discussed by Haselgrove (1985, 21).

Some workers have studied the concentration of sherds on the surface and

Field survey data

213

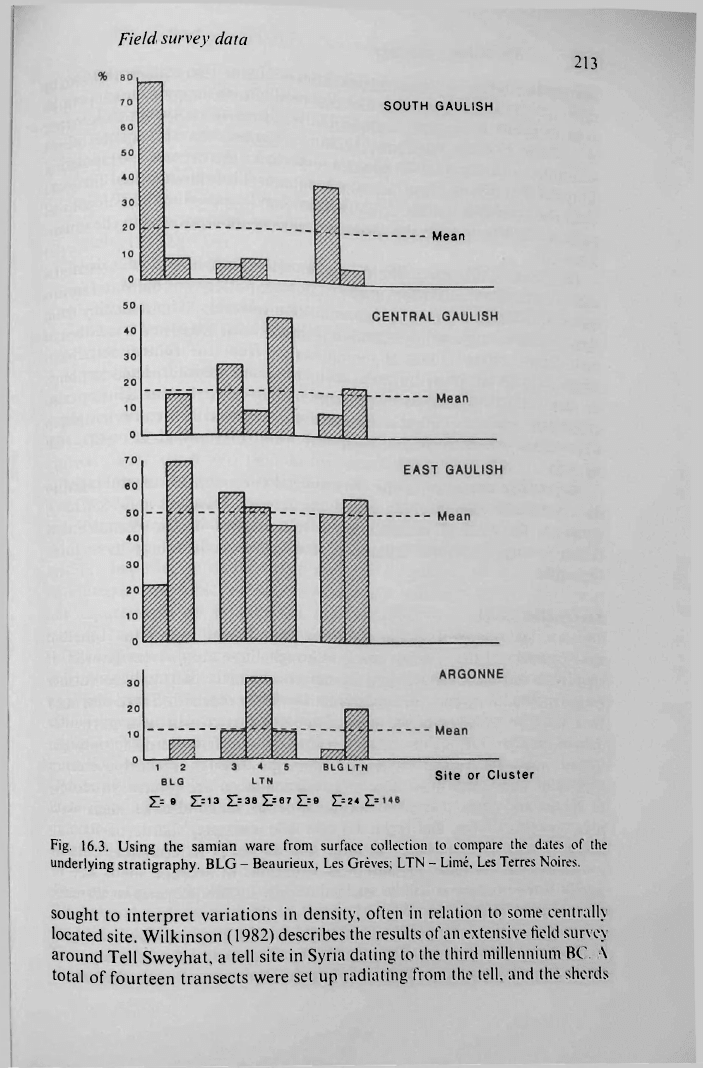

SOUTH GAULISH

Mean

Site or Cluster

5> 9 Z=13 21=38 £>67 H=9 2>24 5>

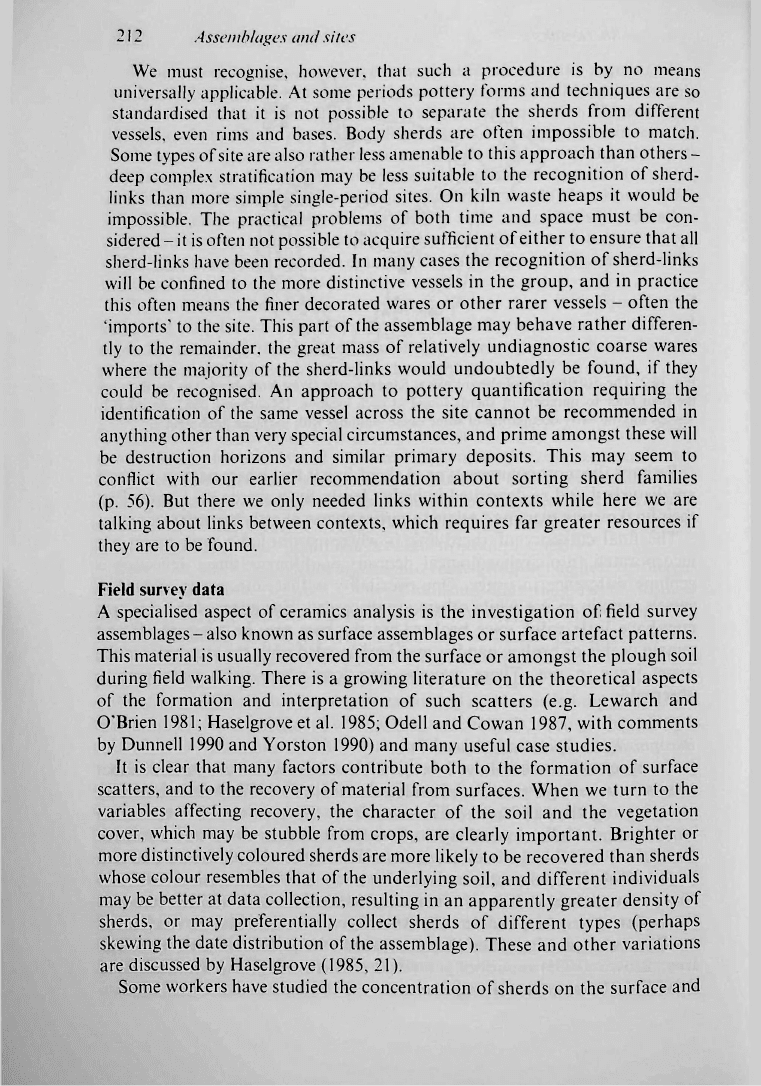

Fig, 16.3. Using the samian ware from surface collection to compare the dates of the

underlying stratigraphy. BLG - Beaurieux, Les Grèves; LTN - Limé, Les Terres Noires.

sought to interpret variations in density, often in relation to some centrally

located site. Wilkinson (1982) describes the results of an extensive

field

survey

around Tell Sweyhat, a tell site in Syria dating to the third millennium BC. A

total of fourteen transects were set up radiating from the tell, and the sherds

214 Assemblages and sites

seen on the surface were counted in a series of 10m x 10m squares at 100m or

500m intervals. The sherd densities observed allowed a contour map to be

constructed which suggested a gradual fall-off from the tell, with the greatest

densities within 3km of the centre. Wilkinson suggests that this equates with a

manuring zone about 30-35 minutes walk from the centre. Extrapolating

from the data obtained from the sample squares it is estimated that there are

8-10 million sherds on the surface within 3km - approximately 56 tons of

pottery - and many times this quantity would be incorporated in the under-

lying soil.

The survey in the area of Maddle Farm on the Berkshire Downs yielded a

more complex picture

(Gaffney

et al. 1985). Here pottery was collected from a

series of 100m north-south transects at 25m intervals. The densities from

these transects, subjected to a trend-surface analysis, suggested a number of

high-density concentrations at some distance from the central settlement

which seem unrelated to permanent occupation and are interpreted as points

of seasonal activity such as dung-heaps or hay-ricks. Lower density con-

centrations nearer the central settlement are interpreted as areas where sheep

were folded, which would not need manuring (Gaffney et al. 1985, 103,

fig. 8.5).

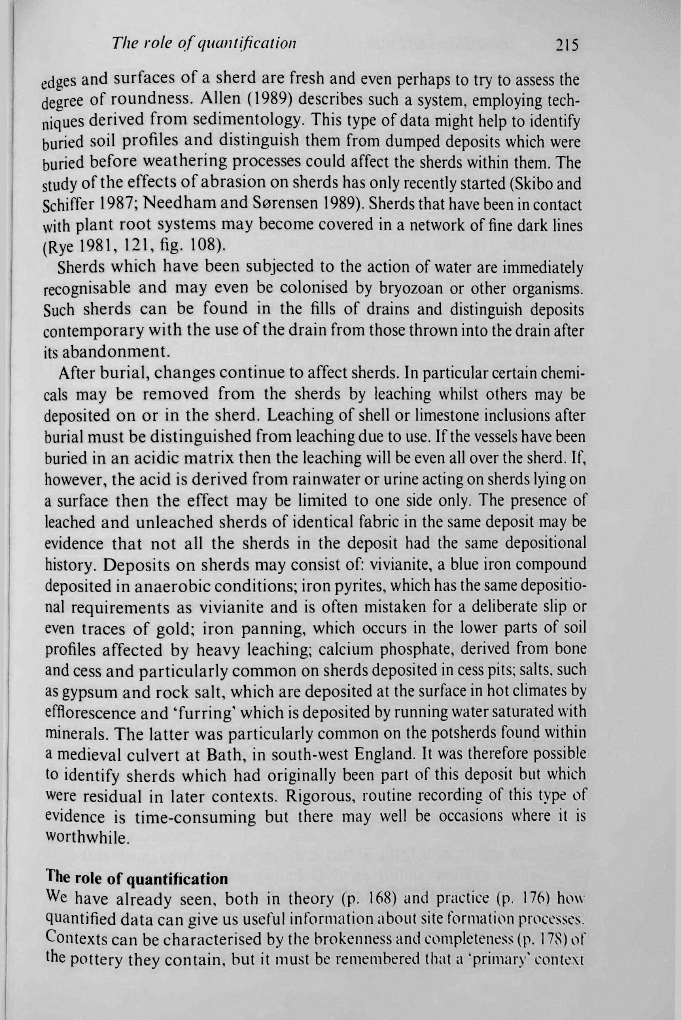

Others have attempted to use the material from surface assemblages to

illustrate the chronology of the underlying activity. Haselgrove (1985, 26-7)

compares the dates of occupation of Roman sites in the Aisne Valley

(France) using the overall balance of the samian assemblage as a guide

(fig. 16.3).

Sherds after burial

The size and shape of sherds does not just depend upon the inherent

characteristics of the original vessel, although these cannot be ignored. If

sherds are left on a surface used by man or animals they will be further

fragmented until perhaps an equilibrium has been reached. Sherd size may

be a valuable indicator of the type of activity carried out in a particular

area of the site, although one must bear in mind that few sherds actually get

buried where the vessels broke and most go through several cycles of

deposition and redeposition. Size and fragmentation are related so closely

to fabric and form that it is not possible to make use of such data

independent of fabric and form. To give one example, sherds of Roman

amphora may be individually as large and as heavy as complete colour-

coated beakers. In these circumstances variations in average sherd size or

weight between contexts will be affected unduly by the presence or absence

of particular vessel types.

In sedimentology it is possible to classify detrital fragments by the degree

of roundness of their edges. The edges of sherds too will reflect the degree of

weathering they have undergone and it can be important to note whether the

The role of quantification

215

edges and surfaces of a sherd are fresh and even perhaps to try to assess the

degree of roundness. Allen (1989) describes such a system, employing tech-

niques derived from sedimentology. This type of data might help to identify

buried soil profiles and distinguish them from dumped deposits which were

buried before weathering processes could affect the sherds within them. The

study of the effects of abrasion on sherds has only recently started (Skibo and

Schiffer 1987; Needham and Sorensen 1989). Sherds that have been in contact

with plant root systems may become covered in a network of

fine

dark lines

(Rye 1981, 121, fig. 108).

Sherds which have been subjected to the action of water are immediately

recognisable and may even be colonised by bryozoan or other organisms.

Such sherds can be found in the fills of drains and distinguish deposits

contemporary with the use of the drain from those thrown into the drain after

its abandonment.

After burial, changes continue to affect sherds. In particular certain chemi-

cals may be removed from the sherds by leaching whilst others may be

deposited on or in the sherd. Leaching of shell or limestone inclusions after

burial must be distinguished from leaching due to use. If the

vessels

have been

buried in an acidic matrix then the leaching will be even all over the sherd. If,

however, the acid is derived from rainwater or urine acting on sherds lying on

a surface then the effect may be limited to one side only. The presence of

leached and unleached sherds of identical fabric in the same deposit may be

evidence that not all the sherds in the deposit had the same depositional

history. Deposits on sherds may consist of: vivianite, a blue iron compound

deposited in anaerobic conditions; iron pyrites, which

has

the same depositio-

nal requirements as vivianite and is often mistaken for a deliberate slip or

even traces of gold; iron panning, which occurs in the lower parts of soil

profiles affected by heavy leaching; calcium phosphate, derived from bone

and cess and particularly common on sherds deposited in cess

pits;

salts, such

as gypsum and rock salt, which are deposited at the

surface

in hot climates by

efflorescence and 'furring' which is deposited by running water saturated with

minerals. The latter was particularly common on the potsherds found within

a medieval culvert at Bath, in south-west England. It was therefore possible

to identify sherds which had originally been part of this deposit but which

were residual in later contexts. Rigorous, routine recording of this type of

evidence is time-consuming but there may well be occasions where it is

worthwhile.

The role of quantification

We have already seen, both in theory (p. 168) and practice (p. 176) how

quantified data can give us useful information about site formation processes.

Contexts can be characterised by the brokenness and completeness

(p. 178)

of

the pottery they contain, but it must be remembered that a 'primary' context

216 Assemblages and sites

may nonetheless have a very high level of brokenness (for example pottery

trampled in situ). When comparing contexts, the different parameters of

different types of pottery must be taken into account if there are different

proportions of

different

types in the contexts. But provided such 'nuisance'

parameters are allowed for, useful information can be obtained.

17

POTTERY AND FUNCTION

The problem of function is perhaps one of the more difficult faced by those

studying archaeological ceramics. The topic can be approached from three

points of view: firstly at the level of the function of the individual vessel;

secondly the functional information that can be recovered from archaeo-

logical assemblages; and thirdly the overall orientation of a particular indus-

try

- the sector of ceramics usage at which the principal products are aimed.

To tackle all these aspects adequately it is necessary to draw together

information on form, nomenclature, fabric, technology, trade, distribution

and site formation processes as well as historical, ethnographic and literary

references. It is perhaps not surprising that so much remains to be done, for

some of the necessary tools, such as the appropriate statistical techniques for

comparison between assemblages or the analytical techniques for identifying

organic residues, have only recently become widely available. It is also not

entirely clear what results may be expected from studies of vessel or assem-

blage function or how such information is to be integrated into site reports or

regional surveys.

Individual vessel function

Artefacts made of fired clay are ubiquitous and their functions are diverse.

Ceramic bricks, tiles, pipes and other forms of building materials are very

common, and tubes, funnels and fittings for other industrial processes take

advantage of the refractory properties of fired clay. Moulded and fired clay

figurines have a long history and the use of clay as a medium for figurative art

continues to this day. Pottery baths, sarcophagi, portable ovens and similar

exotica have been produced at some periods, but perhaps the most important

function of ceramics, both now and in the past, has been its use as containers,

particularly for the storage, preparation, movement and serving of food.

Functional

categories

The functions of pottery containers can be divided into three broad cate-

gories: storage, processing (which includes various cooking methods) and

transfer (including serving and eating) (Rice 1987, 208-9). Without too much

difficulty we can imagine that a vessel employed as a long-distance transport

container for a liquid will tend to have characteristics (durability, ease-of-

handling and stacking, weight/volume ratio, low porosity, scalable top and so

217

218 Pottery and function

on) that are rather different from those required by a vessel whose primary

function is the frying of eggs (thermal shock resistance, accessibility, smooth

or non-stick surface, perhaps even a nice flavour - Arnold 1985, 138—9). An

extension of this approach is to survey ethnographic and historical records

for correlations between aspects of

form,

technology or other characteristics

and vessel function (Hendrickson and McDonald 1983; Smith 1985). Rice has

summarised the 'predicted archaeological correlates' for five broad func-

tional categories: storage, cooking (food preparation with heat), food prepar-

ation without heat, serving and transport (Rice 1987, table 7.2). Such summa-

ries may be a useful means of organising the available information, but many

of the decisions taken during the manufacturing process require compromises

between competing requirements, so in a particular instance a predicted

correlate may be masked by some other factor. There will also be vessels that

have to fit into more than one category. Cooking vessels produced for an

export trade may acquire some of the characteristics of transport containers,

such as stackability and uniformity of size.

Written sources and pictorial representations

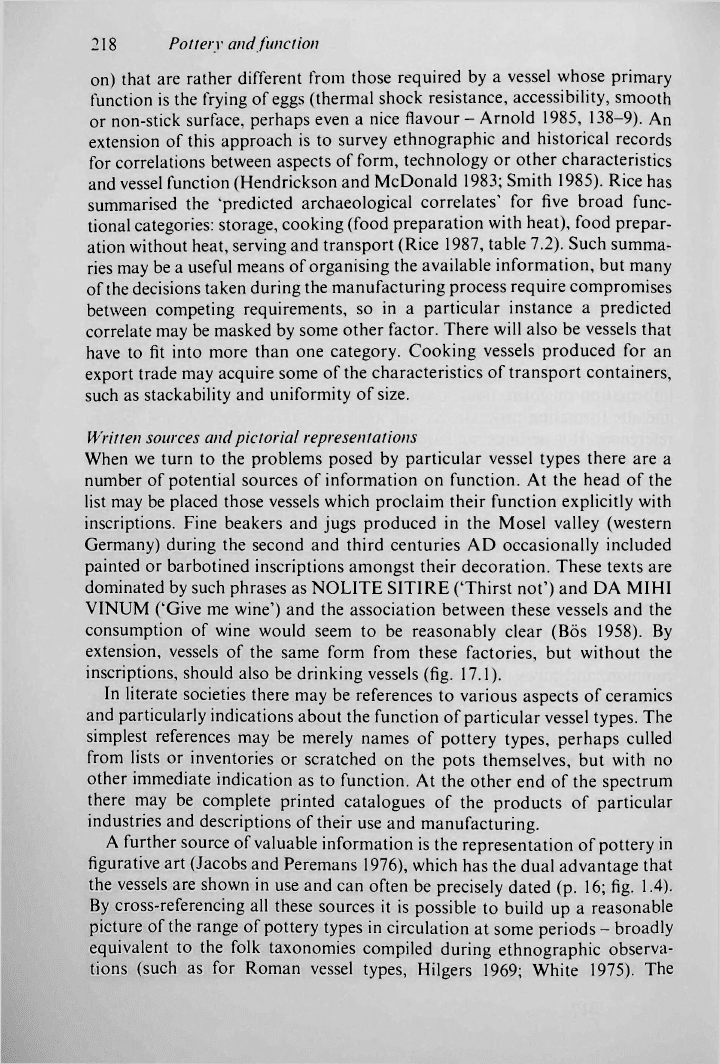

When we turn to the problems posed by particular vessel types there are a

number of potential sources of information on function. At the head of the

list may be placed those vessels which proclaim their function explicitly with

inscriptions. Fine beakers and jugs produced in the Mosel valley (western

Germany) during the second and third centuries AD occasionally included

painted or barbotined inscriptions amongst their decoration. These texts are

dominated by such phrases as NOLITE SITIRE (Thirst not') and DA MIHI

VINUM ('Give me wine') and the association between these vessels and the

consumption of wine would seem to be reasonably clear (Bos 1958). By

extension, vessels of the same form from these factories, but without the

inscriptions, should also be drinking vessels (fig. 17.1).

In literate societies there may be references to various aspects of ceramics

and particularly indications about the function of particular vessel types. The

simplest references may be merely names of pottery types, perhaps culled

from lists or inventories or scratched on the pots themselves, but with no

other immediate indication as to function. At the other end of the spectrum

there may be complete printed catalogues of the products of particular

industries and descriptions of their use and manufacturing.

A further source of valuable information is the representation of pottery in

figurative art (Jacobs and Peremans 1976), which has the dual advantage that

the vessels are shown in use and can often be precisely dated (p. 16; fig. 1.4).

By cross-referencing all these sources it is possible to build up a reasonable

picture of the range of pottery types in circulation at some periods - broadly

equivalent to the folk taxonomies compiled during ethnographic observa-

tions (such as for Roman vessel types, Hilgers 1969; White 1975). The

Individual vessel function

219

Fig. 17.1. A beaker made in the Mosel valley during the third century AD with a painted

inscription suggesting that the vessel was intended for drinking wine. (Photo* David Allan)

information on pottery use that can be derived from the examination of such

pictorial sources extends to such items as the wicker handles added to jars to

turn them into water carrying vessels (e.g. Faure-Boucharlat 1990,92), or the

basketwork used to protect vessels during transport (Laubenheimer 1990, S2,

85, 101). These of course would rarely survive in archaeological contexts. In