Peterson A.T., Hewitt V., Vaughan H., Kellogg A.T. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Clothing through American History, 1900 to the Present. Volume 1: 1900-1949

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Nearly four years after WWII many European countries, the United

States, and Canada were still fearful of attacks from other countries. In

April 1949, they created a military alliance called the North Atlantic

Treaty Organization (NATO). The member countries agreed to come to

the defense of any other member country that was being attacked by an

outside country.

ETHNICITY IN AMERICA

Jim Crow laws, a set of state and local laws in the American South,

allowed ‘‘separate, but equal ’’ treatment and accommodation for African

Americans and whites. ‘‘Separate, but equal’’ meant that African Ameri-

cans and whites had separate schools, public bathrooms, and entrances to

buildings. Invariably, the accommodations for African Americans were in-

ferior to those of whites. After WWII, the Civil Rights Movement to

eliminate these laws began to gain momentum. The U.S. Supreme Court

began to rule some of these laws as unconstitutional. For example, the

courts deemed segregation in interstate transportation was unconstitu-

tional in 1946 in Irene Morgan v. Virginia.

The sacrifice of African Americans during WWII brought renewed

scrutiny to their treatment. Section 4(a) of the 1940 Selective Service Act

clearly banned discrimination based on race or color. Even though the

U.S. military was fighting against a racist dictator, Hitler, President

Roosevelt refused to integrate the armed forces, believing it would under-

mine military discipline and morale during a time of national crisis. Dur-

ing the war, the Marine Corps excluded African Americans, the Navy

used them as servants, and the Army created separate regiments for them.

In 1948, President Truman abolished racial segregation in the U.S. armed

forces.

African-American women fared better than their male counterparts

in the military. The Federal Nurses Training Bill prohibited racial bias

in selection of candidates for nurses training, which allowed thousands of

African-American women to enroll in the Cadet Nurse Corps. Many of

them reached officer ranks, and the remarkable contributions of the more

than 59,000 women in the army nurse corps helped to keep the mortality

rate among American military forces very low (Willever-Farr and Para-

scandola, n.d.).

Native Americans played a unique role during WWII: they became

the secret weapon that assisted the Marines in taking key Pacific holdings

from the Japanese. Their secret was the Navajo language; its complexity

made it the perfect unbreakable code. Race friction was not commonplace

50

POLITICAL AND CULTURAL EVENTS

in the Marine Corps. The men worked together and depended on each

other (Paul 1973).

The concept of racial purity espoused by the Nazis disturbed many

Americans. Congress passed the Alien Registration Act of 1940, which

encouraged noncitizens to become citizens. The initiative was a success,

with almost 1 million people acquiring citizenship between 1943 and

1944. The country’s ideal was to merge the ethnicities into a single Ameri-

can society, but nonwhites were not welcomed into this ideal.

Although Mexican Americans were encouraged to serve in the mili-

tary during the war, they tended to be given menial positions. In 1943,

racial tensions flared when a group of white soldiers heard a false report

that a Mexican American had beaten a white sailor. The ensuing violence

was named the Zoot Suit Riots, after the distinctive suits worn by young

Mexican Americans and African Americans. When there was a labor

shortage for field workers in 1942, the U.S. government allowed thou-

sands of Mexican immigrants to cross the border to work on farms in the

southwest.

Regardless of ethnicity, anyone who served in the armed forces could

take advantage of the G.I. Bill. The bill provided money for education,

and 8 million veterans took advantage of the bill and went to school

rather than return directly to work. Education and professional status

were now available to all ethnicities and income levels, but many schools

had admissions policies that discriminated against women and blacks.

REFERENCES

Abbott, B. 1973. Changing New York: New York in the Thirties. New York: Dover.

Andrist, R. K., ed. 1970. The American Heritage History of the 20s & 30s. New

York: American Heritage Publishing Co., Inc.

Baker, P. 1992. Fashions of a Decade: The 1940s. New York: Facts on File.

Barlow, A. L. 2003. Between Fear and Hope: Globalization and Race in the United

States. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Berkin, C., Miller, C. L., Cherny, R. W., and Gormly, J. L. 1995. Making Amer-

ica: A History of the United States. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Gordon, L., and Gordon, A. 1987. American Chronicle. Kingsport, TN: Kingsport

Press, Inc.

Kurian, G. T. 1994. Datapedia of the United States, 1790–2000. Lanham, MD:

Bernan Press.

Matanle, I. 1994. History of WWII, 1939–1945. Little Rock, AR: Tiger Books

International.

McKay, J. P. 1999. A History of Western Society. New York: Hougton Mifflin.

The 1940s

51

Murrin, J. M., Johnson, P. E., McPherson, J. M., Gerstle, G., Rosenberg, E. S.,

and Rosenberg, N. 2004. Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American

People, Vol. 2 since 1863. Belmont, CA: Thomson.

Perrett, G. 1982. America in the Twenties, A History. New York: Simon and

Schuster.

Reeves, T. C. 2000. Twentieth Century America: A Brie f History. Oxford: O xford

University Press.

Zinn, H. 1995. A People’s History of the United States. New York: Harpers

Perennial.

52

POLITICAL AND CULTURAL EVENTS

3

Art and Entertainment

In the first decade of the 1900s, art and entertainment had more in

common with the previous century that it did with the next decades.

Technological advances had a profound effect on the first half of the

twentieth century. Not only did it shape the media being used, but it

shaped the artists as well.

The artists working in the first decade used a realistic style and subject

matter. They glorified American landscapes whether they were mountains,

plains, or shining seas. They also used gritty urban life as subject matter

and were subsequently scolded by critics who dubbed these compositions

as ‘‘Ash Can’’ art.

Refinements in photographic technology allowed ordinary people to

own and easily operate a camera. Americans captured their lives and the

landscapes and people around them. Documentary photographers became

more prevalent and captured images of the less-glamorous side of Ameri-

can life.

Literature in the 1900s often included a moral message or a reflection

of societal values. Horatio Alger stories were a popular example of this

type of literature. The hero would begin the story in a desperate position,

but through his hard work and good values, he would achieve success.

Reformers also used literature to disseminate their messages.

Popular music in the first decade of the century was a break from

the past. Ragtime music emerged, and dance halls became a favorite

53

entertainment spot. Theater was a widespread pastime in urban areas,

whereas traveling and regional groups frequented rural areas. Vaudeville,

operettas, and comedies were popular genres.

In the 1910s, realism was still a widely used artistic style, but cubism

emerged on the scene. Its two-dimensional geometric compositions were a

strong contrast to other styles. Photographic technology made additional

advances, allowing advances in motion pictures. The first full-length pic-

ture was released during this decade, and the concept of the ‘‘movie star’’

was created.

The audiences for art widened over the decade. Musical theater drew

large audiences, and literature became more widely available. In the case

of literature, the wide dissemination drew criticism of literary subject mat-

ter and a call for censorship. Ethnic music, although it had existed before,

saw a wider distribution than in previous decades.

The 1920s were fertile with artistic movements, including art deco,

Bauhaus, cubism, Dadaism, and surrealism. These movements permeated

nearly all art forms from paintings and sculpture to architecture and liter-

ature. By the end of the decade, this generation of artists had thoroughly

broken with the past.

The Jazz Era began during the 1920s by starting in small clubs. By

the end of the decade, the style had been incorporated into big bands and

was on its way into mainstream popularity in the 1930s. Energetic danc-

ing to this fast-tempo music dominated dance halls.

Motion pictures made their leap to ‘‘talkies.’’ Although some actors

saw their careers vanish because their voices did not fit their portrayals,

the new technology set the stage for the popularity of musicals in subse-

quent decades. Stars existed in every genre, and movie studios generated

enormous publicity campaigns to keep their stars in the limelight.

During the 1920s, radio had emerged from its infancy. More and

more households acquired a radio, not just for newscasts but for concerts,

comedy and drama programming, and the incredibly popular sporting

events.

Art deco and surrealism continued to remain popular in the 1930s.

Art deco especially fit in with the minimalism brought on by the Great

Depression. The Depression also renewed the artistic interest in rural

America and regionalism. The United States witnessed an influx of Euro-

pean artists who fled as Adolph Hitler’s aggressions intensified.

By the mid 1930s, big band music was mainstream and requisite in

dance halls. Technological innovations in music recording and radios

helped publicize new music styles and new artists. By the end of the dec-

ade, radio programming became stable, and advertisers were a staple in

54

ART AND ENTERTAINMENT

most popular programs. FDR reached out to Americans via the radio in

his fireside chats.

Despite the economic hardships of the decade, movies continued to be

a popular attraction. American audiences visited the movie theater as of-

ten as they could, often weekly. The demand and interest in stars kept the

movie studios’ publicity machines going. The United States Motion Pic-

ture Production Code was enacted during this decade and imposed tight

moral restrictions on movie studios.

In the 1940s, artists embraced Modernism, and some, such as Jackson

Pollack, used Abstract Expressionism. The arts became more introspective

and focused on the individual, whether it was created by a visual artist,

musician, or writer.

During WWII, big band music remained popular, and it served as a

reminder of home to the troops abroad. Increasingly, vocalists were fea-

tured in compositions and became popular in their own right. After the

war, Bebop and Cool Jazz emerged as new musical styles.

Radio matured and nearly every American household owned a set. By

the end of the decade, the new medium of television had taken hold. Af-

ter the war, Americans could afford to purchase these new entertainment

luxuries. As more sets were purchased, programming increased.

Movies were in their golden age during the 1940s. Movie stars gen-

erated huge public interest, and high-caliber movies were being produced

every year. Musicals became extremely popular, and the most bankable

stars could sing, dance, and act. In addition, Hollywood generated numer-

ous comedy shorts, serials, and animation shorts. At the beginning of the

century, no one could anticipate the interest that movies would generate

by the 1940s.

THE

1900S

ART MOVEMENTS

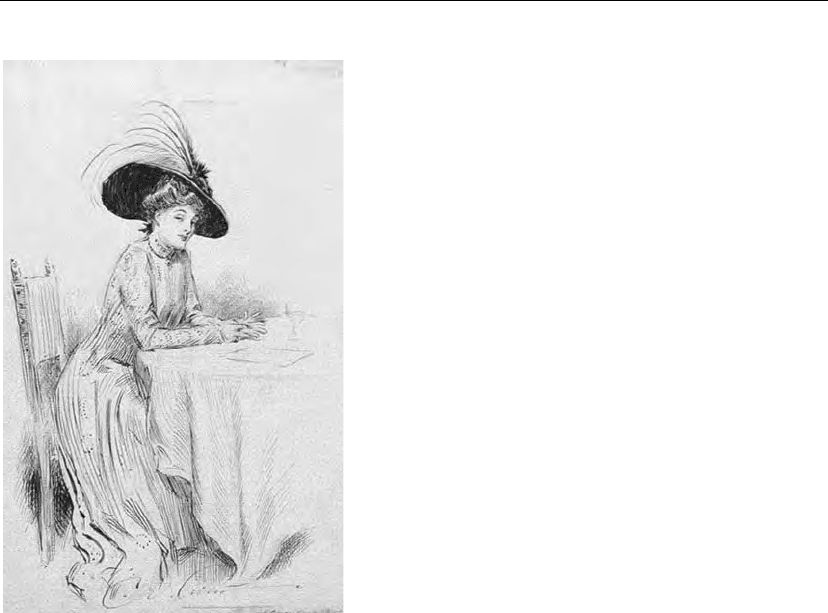

One of the most famous artists of this period was Charles Dana Gibson.

Arguably, his most famous creation was ‘‘the Gibson girl,’’ a young girl

with her hair in curls, shirtwaist blouses, and simple skirts. She became a

model for many young women in the first two decades of the twentieth

century. The Gibson girl was an illustration of the ideal American

woman, admired by working women as well as her wealthier sisters. She

was not obviously a suffragette, nor a temperance advocate slinging an axe

in a saloon.

The 1900s

55

Gibson’s vision indicated a young woman who

was sturdy, self-reliant, and knew what she wanted.

Although not openly advocating any political or

social causes, the Gibson girl would engage in sports,

ride a bicycle without a chaperone, and might, on

occasion, engage in some mild form of strenuous ac-

tivity. She did not faint, nor did she change her

behavior to appeal to men. Women tried to model

themselves after Gibson’s ideal, and men wanted to

marry them.

Not all art was intent at presenting life in a posi-

tive, romantic manner. Perhaps because 1900 was

seen as the beginning of a new millennium and the

United States was growing past its isolationist stages

and branching out into world politics, but in the

1900s, American artists started reconsidering what

‘‘art’’ was. Many of the young artists at the time saw

little point in producing the fantasized illustrations of

life that had been painted for centuries. They wanted

to bring more realism to their work, hence the con-

cept of ‘‘realism.’’

Part of the new trend was a result of finally having artists who were

trained in the United States. During the nineteenth century, most artists

went to Europe to learn the styles of the European masters. After the

Civil War, many families could not afford to send children to Europe.

The economic depressions and the horrors of the war impressed the artis-

tic youth of this country. They began to see what really existed. By the

end of the nineteenth century, artists were painting scenes of their area of

the country. Homer Winslow, from New England, painted dramatic

ocean scenes. Frederick Remington put the lives of common cowboys,

horses, and cattle on canvas. The younger artists were starting to chal-

lenge the way art had been done for decades, if not centuries.

One of the first ar t movements in New York to challenge the status

quo was a group of artists referred to as the Ash Can sc hool. They

painted sc enes of li fe as it really existed on th e streets of New York.

Major museums and art critics deplored this art, but the artists insisted

that it was real and that art should reflect life as it was, not as the artist

wanted it to be. For the first year or two, no one was willing to allow

such artists to disp lay their work, so the artists joined forces and created

their own studios and galleries th at would display the more realistic

scenes of life.

A Gibson girl in

shirtwaist and picture

hat, c. 1910. [Library

of Congress]

56

ART AND ENTERTAINMENT

The century also saw the rudimentary beginnings of mass photography.

The first Kodak camera had been introduced in 1888, and professional and

talented amateur photographers had been taking portraits and pictures of

scenery for years. Frank Brownell developed a small camera called the

‘‘Brownie’’ for George Eastman in 1900. This camera cost $1 and was inex-

pensive enough that most Americans could buy one, making photography,

for the first time, something that anyone could do (Chakravorti 2003).

The Brownie, by the way, was not named after its developer. George

Eastman was aware that children read books about elves and children,

and there was a character called ‘‘Brownie’’ that was popular at that time.

Eastman thought that, if the camera had a name that children would like,

it might catch on, and he was correct.

Architects were able to take advantage of some of the era’s new tech-

nology to ‘‘solve’’ some of the big problems of the cities. People kept

flocking to the cities in hopes of finding work or in hopes of finding a

better life. They needed someplace to live and work. The skyscraper was

born to house offices, but it also could be used to house people. The new

technique of creating steel beams that were strong and light would allow

buildings to be built higher than anyone could have dreamed.

The motto ‘‘form follows function’’ became a trademark of early

American architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Sullivan. Nei-

ther man saw a point to the useless details and ornamentation on many

older buildings. Sullivan’s work stressed the function and the structure of

the building itself. Wright considered Sullivan a master in the field, but

Wright was able to construct buildings that looked as if they were grown

from the area around them. Both men would have major impacts on

American architecture in later decades.

LITERATURE AND MUSIC

Horatio Alger, a poor writer who found a successful formula, was a popu-

lar author for boys’ novels at the turn of the century. The plots of the sto-

ries all concerned young boys who had origins in poverty. The boys leave

their family to seek fortunes elsewhere. These children did not earn their

fortunes, but they were unfailingly polite and good role models for any

young boy. They became wealthy simply because they would do some-

thing quickly and save someone or something, and then they would be

rewarded for their bravery and quick thinking. Alger wanted to demon-

strate to his readers that somehow, their virtuous behavior would be

rewarded. In the world that Alger created in his books, boys who did not

follow the rules tended to be evil or have troubles their entire lives.

The 1900s

57

Girls too had their stories. Many of them were presented as melodra-

mas on a local stage. Frequently, a young girl would be engaged in some

kind of dispute with a very wealthy woman. The wealthy women were of-

ten portrayed as thoughtless and frequently unscrupulous. The wealthy

woman would be doing everything she could to maintain the wealth of

her family and to continue living a life of what many called ‘‘conspicuous

consumption.’’ The poor young girl might be nothing in the rich woman’s

eye, but the plot to the story was obviously meant to demonstrate that the

poor girl was a better person than the rich one. As in Horatio Alger’s sto-

ries, the poor young girl would be rewarded for her virtue by the end of

the story, much like the ending of the Cinderella story. What was rarely

discussed, however, was whether or not the young girl married her rich

husband and then became a conspicuous member of the idle rich.

Much of the popular literature reflected the ideals of the times. Some

of the best known novels of the late 1800s, stories such as Tolstoy’s Anna

Karenina or Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles, reflected stories of

women who, for a variety of reasons, left their husbands for another man.

These fictional women might have some weeks or months of happiness,

but, invariably, they met disaster. The idea was clear: a woman’s place was

with her husband and children.

People who did not live a ‘‘proper life’’ were also the subject of the

many pamphlets and stories that reformers made popular. As the world

started changing, many groups banded together to do something about

that change. Women who joined the Women’s Christian Temperance

Union advocated stories that would demonstrate how someone could start

out on the ‘‘right path,’’ become confused and misguided by ‘‘demon rum’’

or another form of alcohol, and then learn that following the footsteps of

one’s forebears was the path to happiness. Many stories were also written

in which the hero or heroine would be tempted but never gave into the

temptations. Many such stories were aimed at young people. Edgar Rice

Burroughs’ stories about Tarzan preached the virtues of ignoring the fancy

trappings of the city life and living a simple life.

One subtle shift, however, was taking place in literature. At the begin-

ning of the nineteenth century, stories ended with the marriage. The main

characters had met, overcome their obstacles, and ‘‘lived happily ever af-

ter’’ in conjugal bliss. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, how-

ever, stories began with the marriage and then discussed issues related to

family life. Although the idea that a woman could leave her husband was

not a totally acceptable behavior, the literature was beginning to reflect

the reality that married life was not the ‘‘happily ever after’’ that everyone

wanted marriage to be.

58

ART AND ENTERTAINMENT

Literature was changing in others ways as well. Because the population

was more urbanized, stories were focusing on people and the new experi-

ences that the city provided. Many heroines would experiment with single

life and a variety of jobs and men. Women in literature were becoming

less inhibited, and many people did not like it. A variety of attempts were

made to censor some of the new literature; many communities developed

some sort of ‘‘anti-vice’’ committee in an attempt to ensure that youths

were not led astray. The attempts to destroy material deemed improper

only made it more popular.

Newspapers and magazines, although not exactly ‘‘literature,’’ became

a popular form of storytelling. Generally, newspapers told the news. Then

Ida M. Tarbell and Lincoln S teffens wrote what might be called

‘‘exposes.’’ Ida Tarbell documented John D. Rockefeller and his Standard

Oil Company. Steffens started writing about the poverty and the prob-

lems of city living. Originally, these were intended to be simply stories,

but the public reaction was overwhelming. Editors learned that people

would pay to buy anything with a scandalous or sensational story to it.

Editors started hiring people to write more such stories, called ‘‘muck-

raking’’ by President Roosevelt, simply to boost circulation.

One such ‘‘muckraking’’ story was The Jungle, written in 1906 by

Upton Sinclair. The story discussed some of the ‘‘evils’’ of the industrial-

ized cities. Its hero wanted to destroy the capitalist system, so most edi-

tors would not publish it. Sinclair found a socialist newspaper, The Appeal

to Reason, that ran the story, and Sinclair’s novel became popular. When it

was published in book form, even President Roosevelt was supposed to

have a copy. The book, along with some of the other newspaper and mag-

azine stories, started changing people’s minds about living conditions in

the cities. Some believe the book’s popularity caused Congress to pass

laws that would prohibit some of the excesses of the greedier industrial-

ists. This kind of legislation would have been unthinkable even ten years

earlier.

Books were not the only commodity that people considered censoring.

Music was becoming ‘‘evil.’’ Perhaps not the music itself, but the fact that

much music encouraged young people to dance and the way they danced

was horrifying to many adults. Some of the popular tunes during the pe-

riod 1900 1909 were ‘‘In the Good Old Summertime’’ and ‘‘Give My

Regards to Broadway.’’ Rags, such as ‘‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’’ by Irv-

ing Berlin, became popular. Other dances, such as the tango, became very

popular in dance halls before WWI.

One of the greatest sins of the music was that it made people move;

they might wiggle and then move other parts of their bodies, and the

The 1900s

59