Prettejohn E. Beauty and Art: 1750-2000 (Oxford History of Art)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

190 modernism: fry and greenberg

switch from ‘beauty’ to ‘art’ as the key word leads inexorably to

manichaean divisions: between good and bad art, good and bad artists,

good and bad connoisseurs of art.

In the last decades of the twentieth century ‘Greenbergian formal-

ism’ came under powerful attack, both from practising artists and from

academic art historians. At the same time many artists, historians, and

critics rejected modernism and Kantian aesthetics. Greenberg’s crime,

it is often imputed, was to have overvalued the aesthetic. Yet from the

perspective of the preceding discussions, it would appear that the

problem is that his theoretical writing was not aesthetic enough. By

imposing a formalist value system derived from modernist abstraction

on the entire history of art, Greenberg denied the wider range of aes-

thetic response found in such writers as Winckelmann and Baudelaire,

Gautier and Pater. Nonetheless there is something powerful about for-

malist looking, and Greenberg’s writing persuasively shows us the

‘beauty’ of abstract art. In the article of 1959 in which Greenberg

explores the disinterested contemplation of abstract art, there is a hint

of a way out of the dilemma. Greenberg suggests that the kind of

looking encouraged by abstract art—the kind we have called formalist

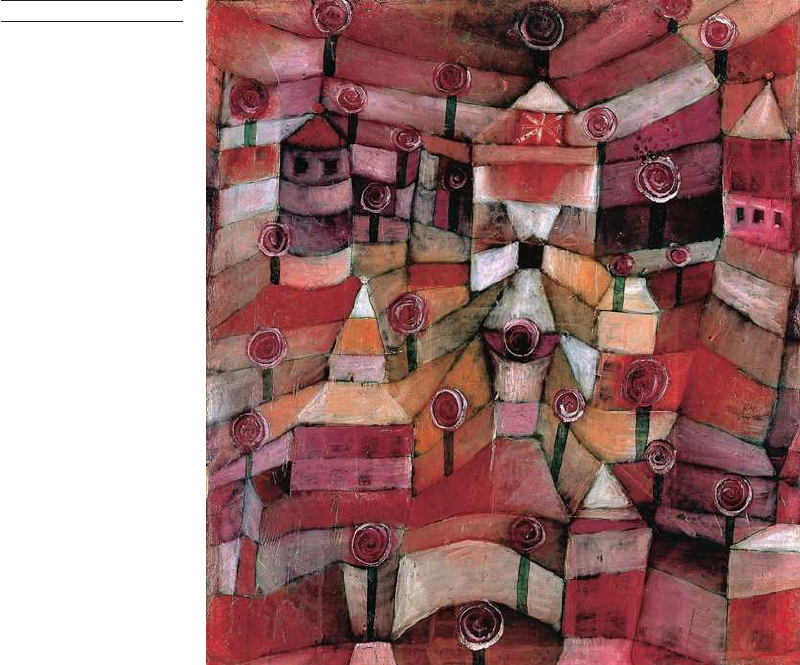

116 Paul Klee

Rose Garden, 1920

modernism: fry and greenberg 191

looking—is a valuable education, teaching us how to attend, seriously

and with sophistication, to visual objects. Abstract art, Greenberg says,

can ‘train us’, can ‘refine our eyes for the appreciation of non-abstract

art’.

48

Formalism might be valuable, then, as a way of teaching our-

selves to see. But we should be philosophically unwise, as well as

foolishly self-denying, if we were to stop there. ‘Beauty’ can give us

more than ‘art’ and more than ‘formalism’.

By the end of the twentieth century, hostility to ‘Greenbergian modern-

ism’ had become a commonplace. In understandable frustration with

modernism’s imperious promotion of its own narrow range of artistic

values, many came to reject aesthetics wholesale, along with mod-

ernism. As the French critic and philosopher Thierry de Duve has

remarked, ‘some are ready to throw the baby out with the bath water—

I mean, Kant’s aesthetics with Greenberg’s’.

1

Thus an influential

collection published in 1983 linked the demise of modernism with

opposition to the aesthetic in its title: The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on

Postmodern Culture. The substitution of the word ‘culture’ for the word

‘art’ is also telling; although most of the essays deal with works that

can easily be categorized as ‘high art’ according to the conventions of

today’s institutions, the word ‘art’ seemed, at this moment in the 1980s,

as suspect as ‘beauty’ or ‘aesthetic’. The preface, by the collection’s

editor, Hal Foster (b. 1955), explains the terminology:

‘Anti-aesthetic’ . . . signals that the very notion of the aesthetic, its network of

ideas, is in question here: the idea that aesthetic experience exists apart,

without ‘purpose,’ all but beyond history, or that art can now effect a world at

once (inter)subjective, concrete and universal—a symbolic totality. Like ‘post-

modernism,’ then, ‘anti-aesthetic’ marks a cultural position on the present: are

categories afforded by the aesthetic still valid?

2

The cloudy language betrays Foster’s weak grasp of the philosophical

tradition he criticizes; as we have seen, the aesthetic (as it has been the-

orized since the late eighteenth century) does not afford ‘categories’,

still less anything that could be described as a ‘symbolic totality’. Yet

Foster rightly identifies an important aspect of modernist art theories,

the categorical separation between the values of art and those of life.

This introduces a powerful new version of the most longstanding

objection to the aesthetic. Where earlier critics such as Ruskin had

attacked the separation of the aesthetic from morality, Foster and many

other critics of the 1980s updated this to denounce what they saw as

modernism’s irresponsible separation of the aesthetic from the social

and political.

Thus the modernist repudiation of beauty was succeeded, in the late

193

Detail of 122

Afterword

194 afterword

twentieth century, by a more strident denial of the aesthetic on political

grounds. Yet the ‘anti-aesthetic’ proposes divisions as manichaean

as those of modernism: between ‘reaction’ and ‘resistance’ (Foster’s

terms),

3

between the ‘aesthetic’ and the ‘political’. This proves as

authoritarian, in its way, as Greenbergian modernism; it simply

replaces formalist criteria for judging art with political ones. Perhaps,

then, it is no surprise that beauty, so strongly associated in the philo-

sophical tradition with freedom, has at last re-emerged in the critical

discourse. After about 1990 calls for a return to beauty began at first

tentatively to emerge in the criticism of contemporary art, then to mul-

tiply. By the turn of the millennium leading academics in the fields of

literature, cultural studies, and philosophy were publishing books on

beauty and the aesthetic (see Further Reading, pp. 211‒12). While this

development has been slow to reach the discipline of art history, several

important exhibitions have explored the question of beauty in recent

and contemporary art. In 1999, for example, the Hirshhorn Museum

and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC, mounted Regarding Beauty:

A View of the Late Twentieth Century.

In the 1990s, then, beauty was once again discussed and debated.

Indeed, the ‘anti-aesthetic’ position of the previous decade had lent a

subversive tinge to the very word ‘beauty’. The paradoxical effect was to

rescue the word from the watered-down connotations that had caused

the early modernists to take issue with it; suddenly beauty was opposi-

tional, challenging, nonconformist. At the same time a number of

writers and artists began to call attention to a different kind of politics:

a politics of gender that permeated the rhetoric of both modernism and

the ‘anti-aesthetic’. Greenberg’s modernism, Newman’s ‘sublime’, and

calls for a politically engaged art all tended to use overtly masculine lan-

guage and terminology; Greenberg’s favourite words of praise are

‘strong’ and ‘major’, while Foster’s are ‘critical’ and ‘resistant’. Beauty,

on the other hand, tended to be denigrated by association with the

feminine or the ‘effeminate’. In this context, beauty could become a

powerful term of opposition to patriarchy, misogyny, and homophobia,

in the writings of such critics as Dave Hickey and Wendy Steiner. As

Hickey comments in The Invisible Dragon: Four Essays on Beauty (1993),

one of the first texts to raise the question of beauty afresh:

the cultural demotic that [formerly] invested works of art with attributes tra-

ditionally characterized as ‘feminine’—beauty, harmony, generosity, etc.—now

validates works with their ‘masculine’ counterparts—strength, singularity,

autonomy, etc.—counterparts which, in my view, are no longer descriptive of

conditions.

Hickey observes, too, that ‘in the Balkanized gender politics of con-

temporary art, the self-consciously “lovely,” i.e., the “effeminate” in art,

is pretty much the domain of the male homosexual’, a situation he calls

afterword 195

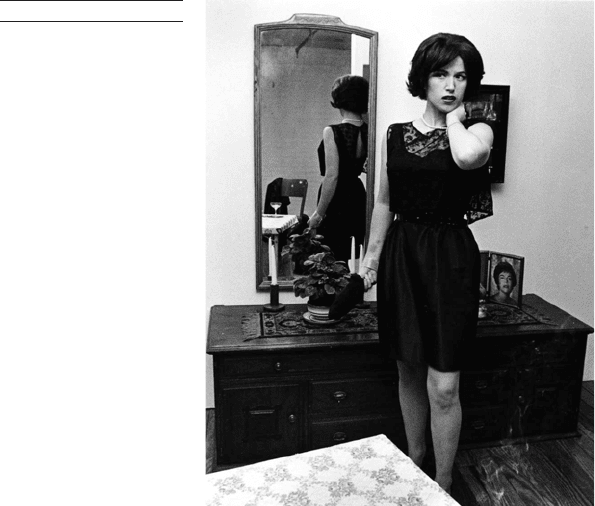

117 Cindy Sherman

Untitled Film Still #14,

1978

‘blatantly sexist (and covertly homophobic)’.

4

Steiner’s The Trouble

with Beauty (2001) argues that beauty, in the western tradition, is so

closely bound up with the representation of the female figure that to

suppress beauty is effectively misogynistic.

5

She quotes the Dutch

artist Marlene Dumas (b. 1953):

(They say) Art no longer produces Beauty.

She produces meaning

but

(I say) One cannot paint a picture of

or make an image of a woman

and not deal with the concept of beauty.

6

Steiner applauds the work of such artists as Dumas and Cindy

Sherman (b. 1954) for raising the question of the female model anew.

In the series of Untitled Film Stills of 1977–80, Sherman photographs

herself as the model in scenarios that recall the glamour of Hollywood

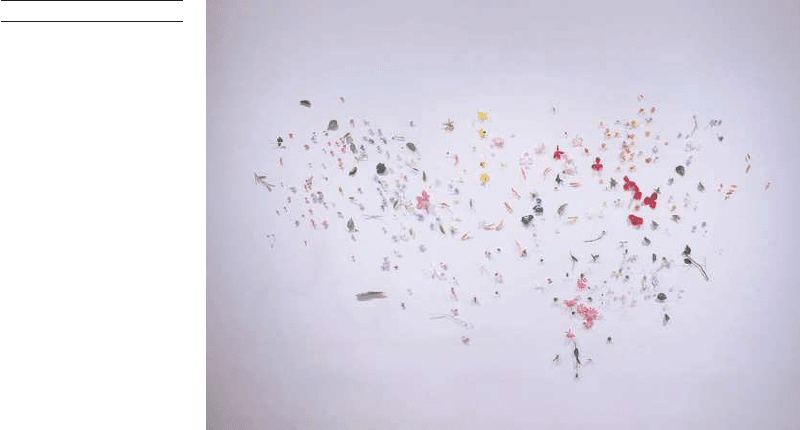

film [117]. In the 1990s, an artist such as Jim Hodges (b. 1957) could

again take up the image of the flower, the most familiar symbol for

both the beautiful and the feminine, in a kind of protest, deliberately

non-aggressive, against the devaluation of such ideas as sentiment,

loveliness, or fragility [118].

By the end of the twentieth century, then, beauty could again be

associated with a progressive politics, as it had been in the eighteenth

century, and often in the nineteenth. Nonetheless, it has proved in-

ordinately difficult to dispel the sense that beauty is somehow a thing of

196 afterword

the past. Even proponents of the new attention to beauty in contempo-

rary art have tended to describe it as a ‘return’ or a ‘revival’ rather than as

a new departure. As both a philosopher and a critic of contemporary

art, Arthur C. Danto has taken a leading role in the reassessment of

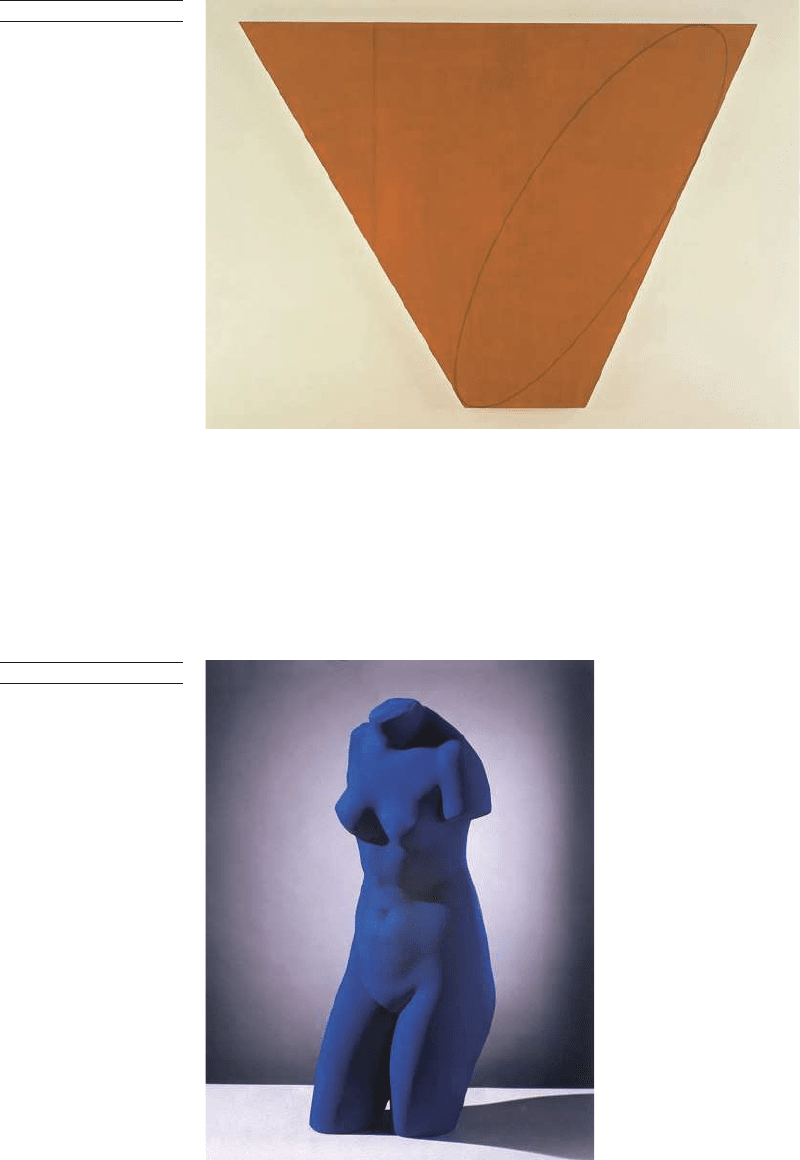

beauty. In a brief article of 1992 entitled ‘Whatever Happened to

Beauty?’, Danto applauds two solo exhibitions, by Dorothea Rock-

burne (b. 1921) and Robert Mangold (b. 1937, 119), for signs of a new

interest in beauty. But he frames this development as a return to the

values of the past: ‘Rockburne and Mangold stand in a certain continu-

ity with a past that unites them with classical antiquity, with marble

forms and cadenced architectures, with clarity, certainty, exactitude and

the kind of universality Kant believed integral to our concept of

beauty.’

7

In the same article, Danto argues against a simple opposition

between aesthetics and politics. Nonetheless, his vocabulary reinforces

the sense that an interest in beauty is somehow conservative.

A return to the past would in some respects be welcome. After all, it

has been an important argument of this book that the explorations of

beauty in the periods before modernism deserve fresh attention. More-

over, artists have often used a return to the distant past as a way of

casting aside more recent artistic conventions, as the many ‘primitivist’

movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries show. We have

seen that Winckelmann proposed a radical return to classical antiquity

to enliven the art of his own day, which he saw as having grown stale

and conventional. Schiller, too, counsels the artist to break decisively

with present-day convention by seeking fresh inspiration in Greek

antiquity: ‘Then . . . let him return, a stranger, to his own century; not,

however, to gladden it by his appearance, but rather, terrible like

Agamemnon’s son, to cleanse and to purify it’.

8

In the later decades of

118 Jim Hodges

Changing Things, 1997

afterword 197

119 Robert Mangold

Attic Series III, 1990

the twentieth century, a number of artists have in effect followed this

advice, by renewing attention to the art of classical antiquity. Mangold

refers to ancient Greek vase painting [119], Rockburne to the architec-

ture of the Roman Pantheon; other artists have even gone back to the

sculptures that Winckelmann and his contemporaries revered. In Blue

Venus [120], the French artist Yves Klein (1928–1962) imbues the forms

of ancient sculpture (compare 80) with his own signature colour, I.K.B.

or ‘International Klein Blue’. The procedure is analogous to that of

120 Yves Klein

Blue Venus, undated

(c.1961–2)

198 afterword

Watts’s The Wife of Pygmalion [86]; in both cases the addition of colour

to sculptural form transforms ancient beauty into modern art. I.K.B. is

a luminous ultramarine that may call to mind the limitless blues of the

sky or sea; coloured thus, the Venus seems almost to float, released from

the gravity of ancient marble. The deep saturation of the blue colour,

with its associations of tranquillity, may be a new way of conveying the

‘noble simplicity and quiet grandeur’ that Winckelmann found in

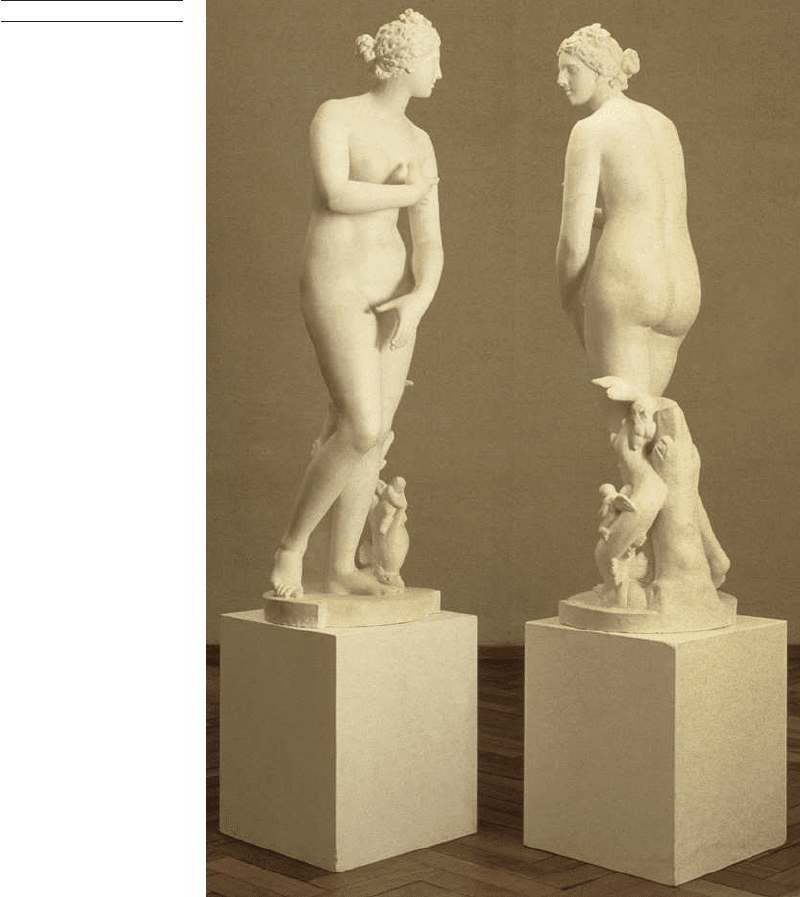

ancient sculpture. The Italian artist Giulio Paolini (b. 1940) draws on

the Venus de’Medici [12] in a work entitled Mimesis, with reference to

the western tradition of artmaking as imitation [121]. The new work is

121 Giulio Paolini

Mimesis, 1975–6

afterword 199

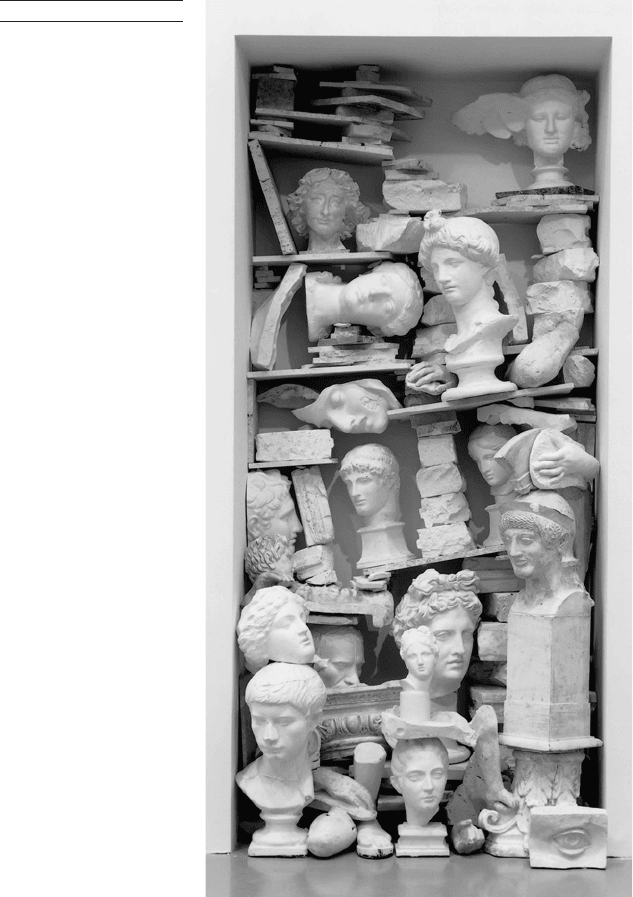

122 Jannis Kounellis

Untitled, 1980

a double imitation, repeating the ancient sculpture twice in the form of

pristine plaster casts. The answering curves of the two casts bring out a

new aspect of the original sculpture, emphasizing the sinuous contrap-

posto of the female body. The two figures are elevated on rectilinear

plinths, which allude to the museum presentation of ancient sculptures

as objects of special reverence; they also suggest the raw block from

which the sculptor creates forms so supple that they persuade us as imi-

tations of the human body. In Untitled [122], the Greek artist Jannis

Kounellis (b. 1936) juxtaposes fragmentary casts of ancient sculpture,

including the head of the Apollo Belvedere [11], within a doorway,