Principles of Finance with Excel (Основы финансов c Excel)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PFE, Chapter 10: What is risk? page 3

Finance concepts discussed

• Ex-post and ex-ante returns

• Holding-period returns

• Treasury bond returns

• Return statistics—mean, variance, and standard deviation

Excel functions used

• Month

• Sqrt

• Average

• Varp

• Frequency

10.1. The risk characteristics of financial assets—some introductory blather

In the course of your life you’ll be exposed to many financial assets. You’ve already

been exposed to them, even if you didn’t know that they were “financial assets”: When you

were small, your parents might have opened a savings account for you at the local bank, or your

grandparents bought you a few shares of stock. Now that you’re a student, you’re stuck with

2

Students reading this book will generally have had a statistics course. This chapter assumes some familiarity with

basic statistical concepts and the next chapter reviews these concepts in the context of financial assets. In this sense

PFE, Chapter 10: What is risk? page 4

student loans, and each month you’re trying to decide whether to pay off your credit card

balances or let them ride for another month and pay interest on them. Once you finish school,

you’ll be taking a car loan, buying a house and taking a mortgage, buying stocks and bonds, … .

All financial assets have different characteristics of horizon, safety, and liquidity. As you

will see, all three of these terms are in some basic sense indicative of the asset’s riskiness. In this

section we briefly review these concepts.

Horizon

Some assets are short-term and others long-term. Money deposited in a checking account

is a good example of a very short-term financial asset; the money can be withdrawn at any time.

On the other hand, many savings accounts require you to deposit the money for a given period of

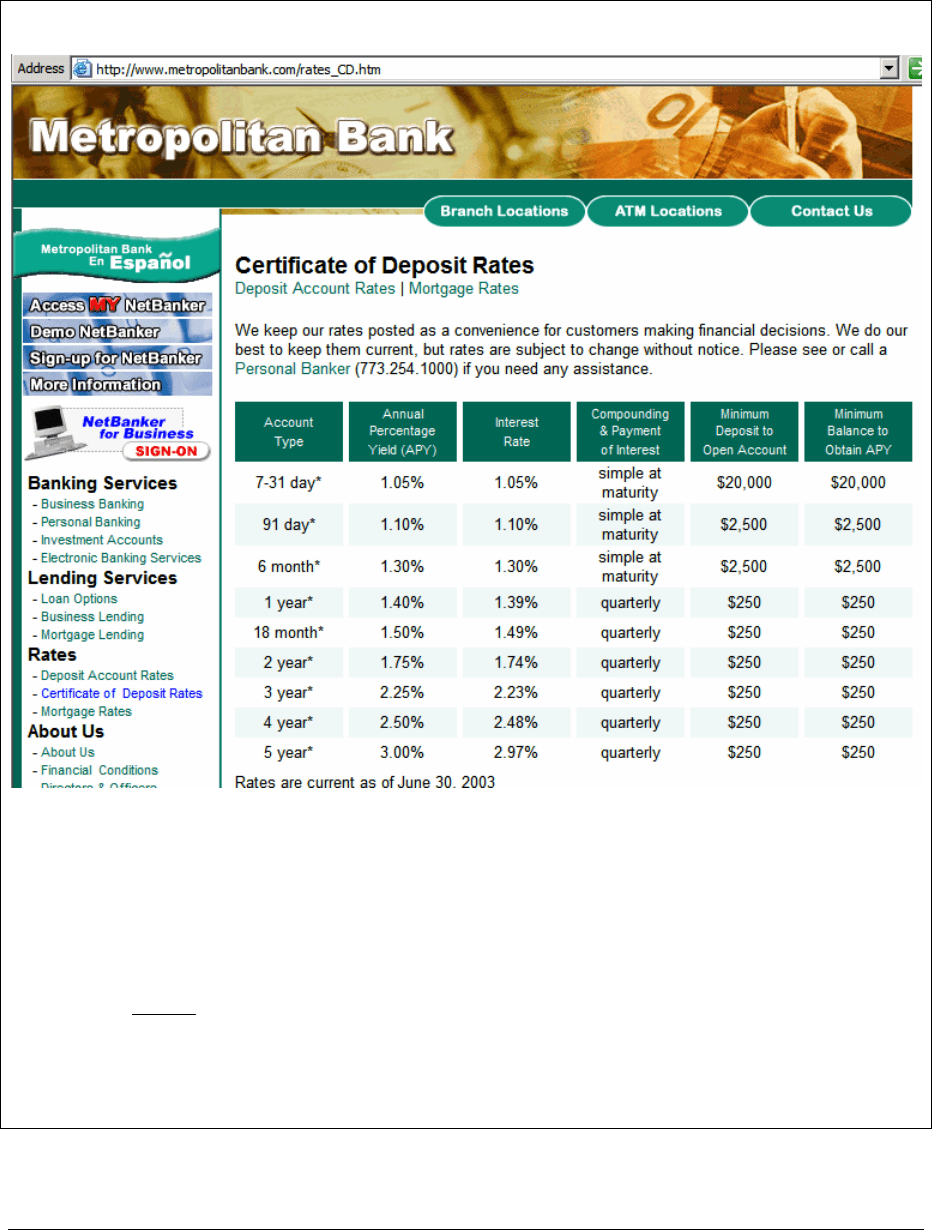

time. Look at Figure 1, which shows the rates offered on certificates of deposit (CD) by

Metropolitan Bank of Chicago. A CD is a time-deposit at a bank—a deposit which cannot be

withdrawn for a certain period of time.

3

Not surprisingly, longer-term CDs offer higher interest

rates.

You’re not always “locked in” to a financial asset with a long horizon. Many long-

horizon assets can be sold in the open market. Suppose, for example, that you buy a 10-year

government bond. You can “cash out” of the bond at almost any time by selling the bond in the

open market, but selling the bond before its 10-year maturity exposes you to the riskiness of an

unknown market price. This subject is explored in detail in Section 10.2 below.

Chapters 10 and 11 are twins.

3

Most banks will allow you to withdraw your money from a CD before the horizon date, but only if you pay a

penalty.

PFE, Chapter 10: What is risk? page 5

Some assets have a long and indeterminate horizon. A share of stock in a company is a

good example. Holding a share of McDonald’s stock, for example, entitles you to whatever

dividends the company pays its shareholders for as long as you hold the stock and the company

exists. You can, of course, sell the stock in the stock market, but this exposes you to the risks of

the stock price fluctuations. In Section 10.3 below we discuss how to analyze the riskiness of

stock holding; this is a topic to which we return in much greater detail in Chapters 11 – 15.

Safety

Financial assets differ in the certainty with which you get back your money. The

Metropolitan Bank CDs in Figure 1 are guaranteed by the Federal Deposit Insurance

Corporation, an agency of the United States government, up to a limit of $100,000. Up to this

limit, the purchaser of a Metropolitan Bank CD will get his money back (including interest),

even if the Metropolitan Bank fails to meet its obligations.

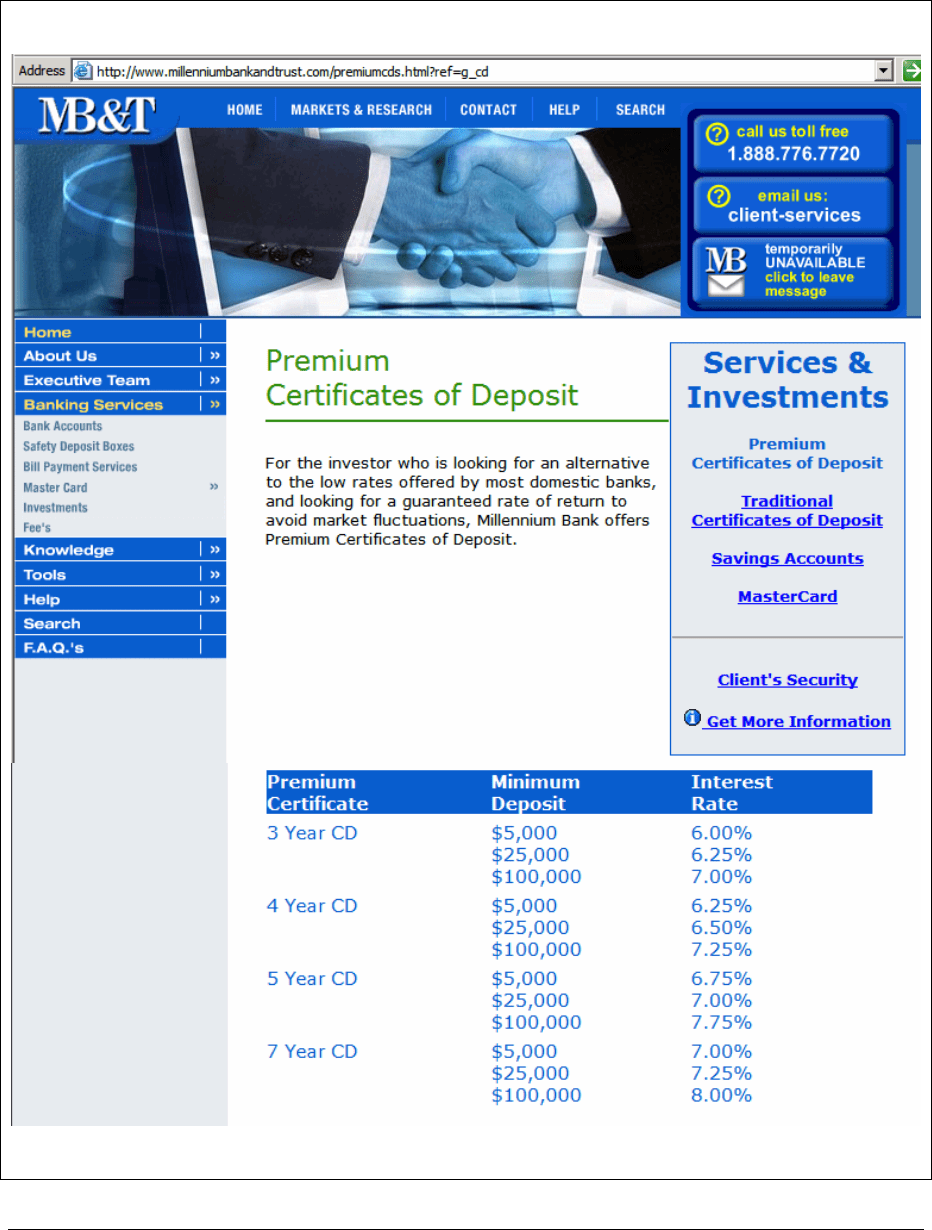

CDs issued by the Millenium Bank and Trust (MB&T) of St. Vincents (a small Carribean

country) pay much higher interest rates (see Figure 2) but are not guaranteed by the U.S.

government. The return on the MB&T CDs is less certain and consequently the interest rates

offered by the bank are higher.

The issuer of a CD announces the interest rate to be paid on the CD and will, presumably,

keep this promise if possible. The same holds for a bond issues by a company or a government.

On the other hand, the issuer of a stock does not give any undertaking about either the stock’s

dividends or the market price of the stock. In this sense the safety of a stock is much less than

the safety of a CD or a bond.

PFE, Chapter 10: What is risk? page 6

In general, the less safe an asset, the greater the return investors will demand and expect

from the asset. Thus, for example, if Metropolitan Bank’s CDs pay interest of between 1% - 3%,

intelligent holders of McDonalds stock (less safe and more uncertain than a CD) should expect a

return greater than 1% - 3%.

This business of “expected return” is complicated:

• If you buy a Metropolitan Bank 5-year CD, you are promised an annual return of 3%.

You will get this annual return with absolute certainty (well, almost absolutely: There’s

always the remote possibility of a catastrophe which prevents both Metropolitan and the

U.S. government from honoring their obligations … ). For the Metropolitan Bank 5-year

CD, the expected return and the actual return received (in economists’ jargon, these are

called the ex-ante and the ex-post returns) are the same.

• If you buy a share of McDonald’s stock, you will expect to get more than 3% annual

return. However, in this case this expectation is merely an anticipated average future

return. In other words: You would be disappointed but not surprised if the actual annual

return on the stock after 5 years was less than 3%.

Liquidity

The ease with which an asset can be bought or sold is the asset’s liquidity. In general, the

more liquid an asset, the easier it is to “get rid off,” and the less its risk.

Listed stocks of major American companies have very high liquidity. For the period

1990-1999, the average daily number of McDonalds shares traded (meaning: shares bought and

sold) on the New York Stock Exchange was 1.5 million shares. This is the average; the highest

number of shares traded daily was almost 12 million and the lowest number of shares was

PFE, Chapter 10: What is risk? page 7

63,000.. If you want to buy or sell a single share of stock (or even several thousand shares),

you’ll have no trouble doing so: McDonalds stock is very liquid.

Liquidity has another aspect, which financial economists call price impact. Suppose you

decided to sell the 1,000 shares of McDonalds stock your father gave you. You’ll have no

trouble selling the stock, but will your sale affect the market price? For McDonalds stock the

answer is “no.”

Not all stocks are equally liquid: Aladdin Knowledge Systems is a small company which

trades on the Nasdaq stock exchange. On an average day around 60,000 shares of Aladdin are

bought and sold, but this number has been as low as 100 shares per day. You would have

relatively little trouble buying or selling several thousand shares of Aladdin stock, but your

action might well affect the market price of the stock. Aladdin is not nearly as liquid as

McDonalds and consequently has greater liquidity risk.

What now?

Horizon, safety, and liquidity all determine the risk of a financial asset. In the succeeding

sections we’ll give some concrete examples. We start by looking at the risks inherent in holding

a U.S. Treasury bill. A T-Bill is completely safe, in the sense that the U.S. Treasury will keep its

obligation to pay back the money borrowed. It’s also very liquid—billions of dollars of T-bills

are bought and sold every day in financial market. However, we’ll show that the horizon of a T-

bill means that it is somewhat risky—if you try to sell it before it matures, the market price is

unpredictable.

From the T-bill we move on to an analysis of the risks inherent in McDonalds stock.

McDonalds stock is not safe in the sense that the company makes no promises about either

PFE, Chapter 10: What is risk? page 8

dividends or the future market price of the stock. We’ll analyze the returns on McDonald stock

over the decade 1990-2000 and we’ll try to make some statistical sense out of these returns.

PFE, Chapter 10: What is risk? page 9

Metropolitan Bank (Chicago) Certificates of Deposit

Metropolitan Bank offers a variety of certificates of deposit (CD). CDs differ by interest

rates and by the amount of time the money is locked up. CDs with longer lock-up times offer

higher interest rates. APY is Metropolitan Bank’s terminology for the effective annual interest

rate (EAIR) discussed in Chapter 2. For example, the 5-year CD pays 2.97% quarterly. This

makes the EAIR 3.00%:

4

2.97%

1 1 3.00%

4

EAIR

=+ −=

Figure 1

PFE, Chapter 10: What is risk? page 10

Millenium Bank and Trust (St. Vincents) Certificates of Deposit

Figure 2

PFE, Chapter 10: What is risk? page 11

IS IT RISK OR UNCERTAINTY?

Frank H. Knight (1885-1972) wrote a dissertation in 1921 called Risk, Uncertainty and

Profit. Knight used risk to mean randomness with knowable probabilities and uncertainty to

mean randomness which is unmeasurable. In finance the distinction between these two concepts

is often blurred and the words “risk” and “uncertainty” are used interchangeably.

10.2. A safe security can be risky because it has a long horizon

Finance people use the words “risk-free” to describe an asset whose value in the future is

known with certainty; “riskless” is a synonym. One classic textbook example of a risk-free asset

is a bank savings account. If you deposit $100 in your bank savings account, which currently

earns 10%, then you know that one year from now there will be $110 in the account. It’s risk-

free.

A United States Treasury bill is another example of a riskless asset. Treasury bills are

short-term bonds issued by the government of the United States.

4

Unlike bank CDs, Treasury

bills do not have an explicit interest rate. Instead they are sold at a discount—a bill with a face

value of $1,000 which matures one year from now might be sold today for $950. In this case the

purchaser of the bill who holds the bill to maturity would be paid $1,000 by the U.S. Treasure

and would thus earn a rate of return of

1, 000

1 5.2632%

950

−= . Since Treasury bills are issue by

the U.S. government, at least one kind of risk—default risk—is absent from these instruments:

4

There are many different kinds of bonds. For a more complete discussion, see Chapter 000.

PFE, Chapter 10: What is risk? page 12

Since the government owns the printing machines which produce dollar bills, they can always

run off a few dollars to make good on their promises.

The purpose of this section is to point out that even Treasury bills—and other financial

instruments which are free of default risk—may have elements of

price risk.

Suppose that on 1 January 2001 you buy a one-year $1,000 U.S. Treasury bill, intending

to hold the bill until its maturity on 1 January 2002. As we said, a Treasury bill doesn’t pay any

interest; instead, it is bought at a discount—that is, for less than its face value. In the case at

hand, suppose you buy the bill for $953.04; since it matures in one year after the purchase, you

anticipated getting interest of 4.93%:

1

2

3

4

5

6

ABCDE

INTEREST ON THE TREASURY BILL

Purchase price 953.04

Payoff on maturity 1,000.00 <-- This is the Treasury bill's face value

Interest 4.93% <-- =B4/B3-1

Now before we start doing fancier calculations, let’s make one thing perfectly clear:

If

you hold the Treasury bill from 1 January 2001 until its maturity 1 year later, you will

absolutely, definitely

earn 4.93% interest. T-bills are obligations of the United States

government and it has never defaulted on them.

In finance jargon the

ex-ante return (sometimes called the anticipated or expected return)

is the return you think you’re going to get. The

ex-post return (also called the realized return) is

the actual return that you get when you sell the asset. For the Treasury bill illustrated here, the

ex-ante return equals the ex-post return

if you hold the bill until maturity. This is always true for

riskless bonds.

Out of curiosity, you track the market price of the bill on the first of each month during

the year. Here’s what you find: