Pumping Station Desing - Second Edition by Robert L. Sanks, George Tchobahoglous, Garr M. Jones

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

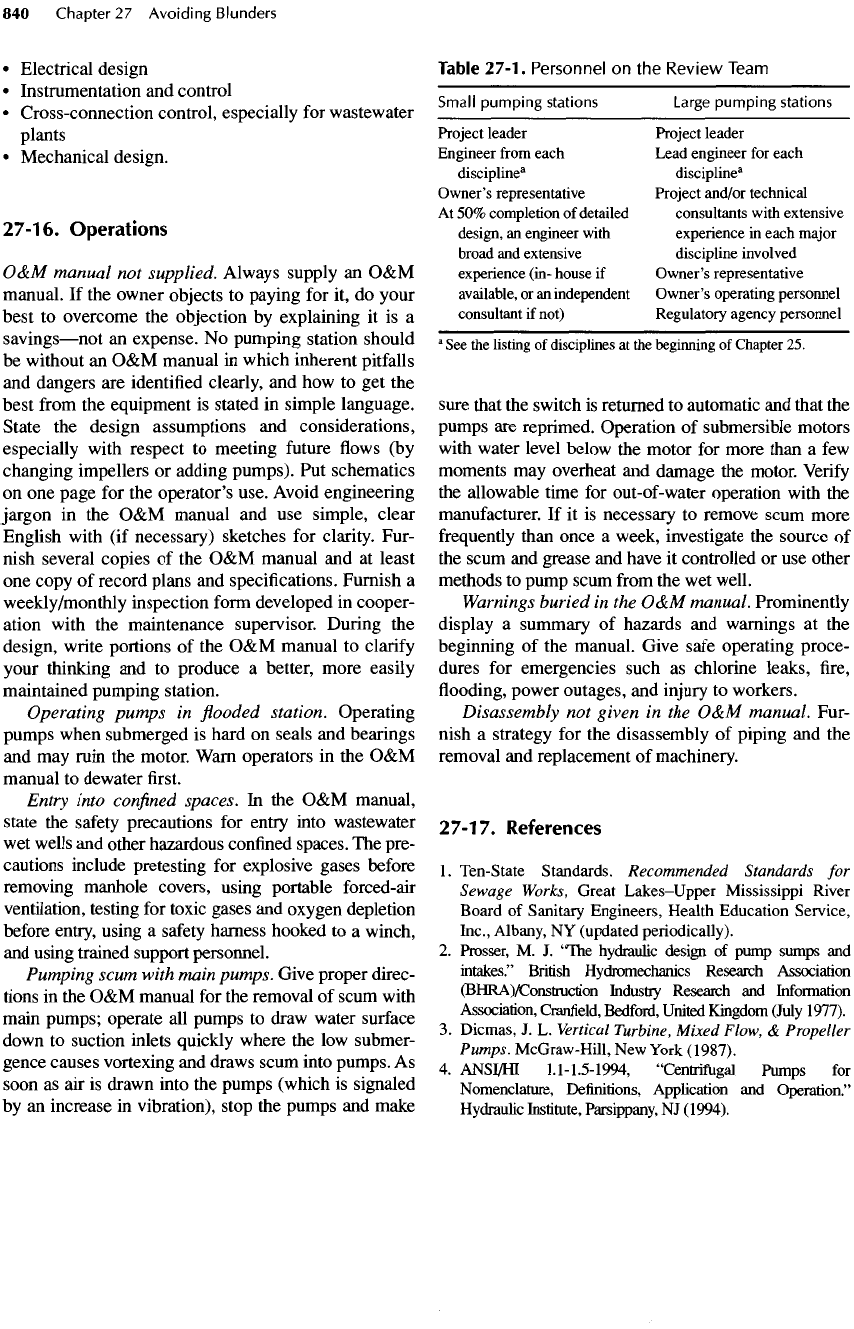

Figure

27-2.

An

actual

low

head sewage

pumping

station.

The

station

has one

60-kW

standby

generator,

(a)

Plan;

(b)

section A-A. Find

10

blunders before

looking

at

the

answers

in

Appendix

D.

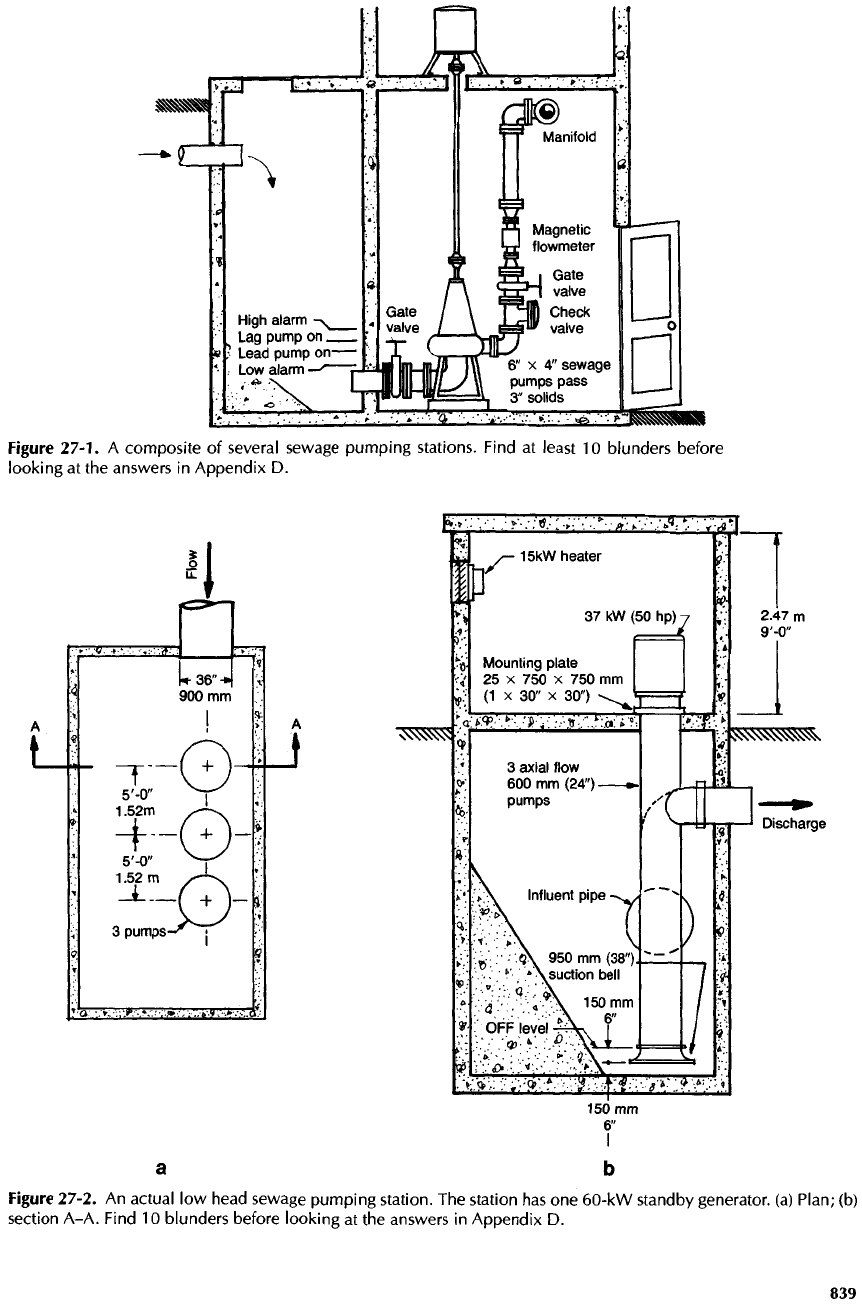

Figure

27-1.

A

composite

of

several sewage

pumping

stations. Find

at

least

10

blunders before

looking

at the

answers

in

Appendix

D.

•

Electrical design

•

Instrumentation

and

control

•

Cross-connection control, especially

for

wastewater

plants

•

Mechanical design.

27-16.

Operations

O&M

manual

not

supplied.

Always supply

an O&M

manual.

If the

owner objects

to

paying

for it, do

your

best

to

overcome

the

objection

by

explaining

it is a

savings

—

not

an

expense.

No

pumping station should

be

without

an O&M

manual

in

which inherent pitfalls

and

dangers

are

identified

clearly,

and how to get the

best

from

the

equipment

is

stated

in

simple language.

State

the

design assumptions

and

considerations,

especially with respect

to

meeting

future

flows (by

changing impellers

or

adding pumps).

Put

schematics

on

one

page

for the

operator's use. Avoid engineering

jargon

in the O&M

manual

and use

simple, clear

English with

(if

necessary) sketches

for

clarity. Fur-

nish

several copies

of the O&M

manual

and at

least

one

copy

of

record plans

and

specifications. Furnish

a

weekly

/monthly

inspection form developed

in

cooper-

ation with

the

maintenance supervisor. During

the

design, write portions

of the O&M

manual

to

clarify

your

thinking

and to

produce

a

better, more easily

maintained pumping station.

Operating

pumps

in flooded

station.

Operating

pumps

when submerged

is

hard

on

seals

and

bearings

and

may

ruin

the

motor. Warn operators

in the O&M

manual

to

dewater

first.

Entry

into

confined

spaces.

In the O&M

manual,

state

the

safety

precautions

for

entry into wastewater

wet

wells

and

other hazardous

confined

spaces.

The

pre-

cautions

include pretesting

for

explosive gases before

removing manhole covers, using portable forced-air

ventilation, testing

for

toxic gases

and

oxygen depletion

before

entry, using

a

safety

harness hooked

to a

winch,

and

using trained support personnel.

Pumping

scum with main pumps. Give proper direc-

tions

in the O&M

manual

for the

removal

of

scum with

main pumps; operate

all

pumps

to

draw water

surface

down

to

suction inlets quickly where

the low

submer-

gence causes

vortexing

and

draws scum into pumps.

As

soon

as air is

drawn into

the

pumps (which

is

signaled

by

an

increase

in

vibration), stop

the

pumps

and

make

Table

27-1.

Personnel

on the

Review

Team

Small

pumping

stations

Large pumping

stations

Project

leader Project leader

Engineer

from

each Lead engineer

for

each

discipline

3

discipline

3

Owner's

representative Project and/or technical

At

50%

completion

of

detailed consultants

with

extensive

design,

an

engineer with experience

in

each

major

broad

and

extensive discipline involved

experience (in- house

if

Owner's representative

available,

or an

independent

Owner's

operating personnel

consultant

if

not) Regulatory agency personnel

a

See the

listing

of

disciplines

at the

beginning

of

Chapter

25.

sure that

the

switch

is

returned

to

automatic

and

that

the

pumps

are

reprimed.

Operation

of

submersible motors

with

water level below

the

motor

for

more than

a few

moments

may

overheat

and

damage

the

motor.

Verify

the

allowable time

for

out-of-water operation with

the

manufacturer.

If it is

necessary

to

remove scum more

frequently

than once

a

week, investigate

the

source

of

the

scum

and

grease

and

have

it

controlled

or use

other

methods

to

pump scum

from

the wet

well.

Warnings

buried

in the O&M

manual. Prominently

display

a

summary

of

hazards

and

warnings

at the

beginning

of the

manual. Give

safe

operating proce-

dures

for

emergencies such

as

chlorine leaks,

fire,

flooding,

power outages,

and

injury

to

workers.

Disassembly

not

given

in the O&M

manual. Fur-

nish

a

strategy

for the

disassembly

of

piping

and the

removal

and

replacement

of

machinery.

27-17.

References

1.

Ten-State

Standards.

Recommended Standards

for

Sewage

Works,

Great

Lakes-Upper

Mississippi

River

Board

of

Sanitary

Engineers,

Health

Education

Service,

Inc.,

Albany,

NY

(updated

periodically).

2.

Prosser,

M. J.

"The

hydraulic design

of

pump sumps

and

intakes." British Hydromechanics Research Association

(BHRAyConstruction

Industry Research

and

Information

Association,

Cranfield,

Bedford, United Kingdom (July

1977).

3.

Dicmas,

J. L.

Vertical

Turbine, Mixed

Flow,

&

Propeller

Pumps.

McGraw-Hill,

New

York

(1987).

4.

ANSI/HI

1.1-1.5-1994,

"Centrifugal

Pumps

for

Nomenclature, Definitions, Application

and

Operation."

Hydraulic Institute,

Parsippany,

NJ

(1994).

This chapter contains

a

brief description

of

what

is

included

in the

project documents,

how

they should

be

prepared,

and a

recommended

format

to be

used.

The

information

given here

in

conjunction with

the

refer-

ences should

be

sufficient

for

guidance

and

assistance

in

the

development

of

clear, concise contract documents.

28-1. General

Project

specifications constitute

the

formal

written

agreement between

the

owner,

who is

paying

to

con-

struct

a

facility,

and the

contractor,

who has

agreed

to

construct

the

facility.

The

legal relationship between

the

primary parties

to the

contract

and the

relationship

of

third parties such

as the

engineer

and the

construc-

tion observer

are

defined

in the

written agreement.

For

the

engineer,

the

term "specifications"

is apt to

indicate

the

detailed description

of

materials, products, perfor-

mance, quality,

and

testing

of

those components

to be

incorporated

in the

project.

But

specifications also

describe

the

entire bidding procedure and, thus, serve

a

function

prior

to the

existence

of a

formal agreement.

Purpose

The

purpose

of the

project specifications

can be

divided

into three parts

as

follows:

•

Bidding documents

Chapter

28

Contract Documents

JOHN

E.

CONNELL

CONTRIBUTORS

David

L.

Eisenhauer

Earle

C.

Smith

•

Contract documents

•

Technical specifications.

Thus, project specifications take

on a

much more gen-

eral role than

the

technical description that accompa-

nies

the

drawings.

The

specifications

are the

official

or

legal commu-

nication between

the

owner

and the

contractor. They

must,

however, address others

in

addition

to the

con-

tractor.

The

specifications

first

address bidders.

These

bidders

are the

prime contractors,

the

subcontractors,

and

the

suppliers

of

products

and

materials.

The

con-

tract agreement addresses

the

successful

bidder

—

the

prime contractor.

The

technical specifications address

the

prime contractor (the party legally responsible

for

their execution) and,

in

practice,

the

suppliers

and

manufacturers.

Addressing

so

many parties presents

one of the

difficulties

in

communicating

the

technical

part

of the

specifications.

A

specification

for a

pump,

for

example, clearly

addresses

all

bidders,

the

prime

contractor,

and the

successful

subcontractor

who

will

supply

the

product. Furthermore,

the

specification

must

ensure both

the

performance

of

suppliers

and the

performance

of the

product through

the

prime con-

tractor,

who is the

legally

responsible

party.

The

specifications

may be

outlined

as

follows:

I.

Bidding. Addresses prospective contractors, sub-

contractors,

and

suppliers.

a.

Advertisement

for

bids

b.

Information

for

bidders

c. Bid

form

d.

Bid

bond

II.

Contract. Addresses

the

prime contractor.

a.

Agreement

form

b.

Payment bond

c.

Performance bond

d.

Notice

of

award

e.

Notice

to

proceed

f

.

Change order

form

g.

General conditions

h.

Special conditions

i.

Addenda

III.

Technical

specifications.

Addresses

the

contractor

directly

and

addresses

the

suppliers

and

manufac-

turers

through

the

contractor.

Specification Language

The

specifications

are a

complex

and

extensive

set of

instructions

that direct

the

contractor.

The

writing style

must

reflect

this objective

by

using clear, positive state-

ments.

The

indicative mood

is

most

effective

in

giving

this

direction

to the

contractor. Language that only sug-

gests

or

implies

an

action

is

likely

to

cause misunder-

standings

or

misinterpretations

of the

true intent

of the

statement. Engineers should

be

precise

in

specifying

what

is

required

in the

manner

of

materials

of

construc-

tion

and

workmanship. Phrases such

as the

following

should

not be

used

in

plans

and

specifications:

•

Suitable

•

Stainless steel (without stating

the

AISI grade)

•

Steel

angle

(without stating

the

ASTM

A 6

designation)

• As

required

• As

necessary

•

Appropriate

• In a

workmanlike manner

•

Of

the

best quality

•

Heavy

duty

•

Industrial grade

•

Commercial grade.

For

accurately describing what

is to be

provided

in

the

contract documents,

the

importance

of

careful

reading before referencing current standards cannot

be

overemphasized.

Format

Choose

a

format

for the

specifications that

is

clear,

logical,

and

consistent

from

section

to

section.

The

format

for

some jobs

is

established

by the

owner. Fed-

eral

and

state agencies

often

require their format

be

used

in

writing specifications. Many consulting com-

panies have their

own

specification format, which uses

a

standard approach

and is set up on a

wordprocessing

system. There

are

also professional

societies,

such

as

the

Construction Specification Institute (CSI) [1], that

support

a

specific

style

and

format (exemplified

in

Appendix

C) or

system

for

writing specifications.

These

societies

have large libraries

of

standard speci-

fications

for

bidding, contract agreements,

and

techni-

cal

specifications.

28-2. Contractual

or

Legal

Documents

Although

the

contract documents include

the

entire

set of

drawings

and

specifications,

it is

common

to

think

of

documents such

as the

bid, agreement,

and

general

and

special conditions

as the

actual contract

documents.

These

documents

are

used

to set out the

basis

for the

owner-contractor

relationship

in a

bind-

ing

contract agreement.

The

documents listed

in

Sec-

tion 28-1 under

"Bidding"

and

"Contract"

are

generally considered

the

contractual

or

legal docu-

ments.

They must

be

coordinated

so

that they

do not

conflict,

and

they must

be

properly referenced.

Special articles

and

paragraphs must

be

added

to

the

bidding

and

contract documents

for

projects

funded

by the

U.S.

Environmental

Protection

Agency

(EPA)

to

satisfy

agency requirements. Become

famil-

iar

with agency requirements

and

include

the

addi-

tional documentation when required.

Standard

bid

documents, agreements, general con-

ditions,

and

other documents

are

published

by

various

professional

engineering

societies.

Perhaps

the

most

useful

to

engineers

are the

documents prepared

by the

Engineers' Joint Contract Documents Committee:

(EJCDC)

[2] and

issued

and

published jointly

by the

National Society

of

Professional Engineers (NSPE),

the

American Consulting Engineers Council (ACEC),

the

American Society

of

Civil Engineers (ASCE),

and

the

Construction Specification Institute (CSI).

The

use of

such documents

is

beneficial because contrac-

tors, engineers,

and

owners become familiar with

their contents. Owners such

as

state agencies, federal

agencies, cities,

or

industries

may

require their

own

set of

documents. Standard forms

and

documents rec-

ommended

by the

American Institute

of

Architects

(AIA)

[3] are

used

for

most private building construc-

tion. Engineering

firms

often

develop their

own

stan-

dard

documents.

There

should always

be a

review

by

an

attorney

to

ensure that

the

content

is

appropriate

for

the

contract.

Advertisement

for

Bids

The

advertisement

for bid

(also known

as the

"invita-

tion

to

bid") should

be

concise

and

must contain

• The

owner's name

and

address

• A

brief statement

of

work

• The

time, place,

and

method

of

placing bids

• The

locations where

bid

documents

may be

obtained

and

information

on

plan

deposit

can be

found

• The

amount

and

type

of bid

surety

•

Special

qualifications

that

may be

required

of

bidders

This document

is

usually published

in the

construc-

tion

or

trade journals

in the

region where

the

project

is

to be

constructed. Government projects usually

require

a

legal advertisement

in a

local

paper,

and the

advertisement

for

such bids must

be

written

to

comply

with

these requirements.

Information

for

Bidders

Information

for

bidders (also known

as

"instructions

to

bidders")

is a

summary

of the

bidding procedure

and

the

requirements

of the

bid.

It is

more detailed

than

the

advertisement

and

contains information

on

preparing

and

submitting

the

bid,

on bid

bonds,

on

performance

and

payment bonds,

and on the

methods

of

evaluating responsive bids

as

well

as a

schedule

and

procedure

for

awarding

the

contract

and

proceeding

with

the

work. Available information

on

existing con-

ditions (such

as

buildings

and

soil information)

and

special requirements (such

as

license

requirements

or

other regulations

affecting

the

contractor)

are

often

mentioned

in the

information

for

bidders. Care must

be

taken

in

preparing this

and all

other documents

so

that

they

do not

conflict

with other parts

of the

specifi-

cations.

To

reduce

the

chance

of a

conflict,

do not

repeat items

that

are

addressed

in

detail elsewhere

in

the

documents. Examples

of

information

for

bidders

are

given

in

EJCDC

and AIA

documents

[2,

3].

Bid

Form

The bid

form

contains elements that

are the

essence

of

the

agreement. These elements

are the

agreed compensa-

tion

for the

work described,

the

time

for

completion

of

the

work,

and the

agreed damages

for

failure

to

complete

the

work

on

time.

All

prices, whether

for a

lump

sum or a

unit-price

contract,

are

given

in

words

and figures. If

there

is a

discrepancy,

the

amount

in

words governs.

The

time

of

completion

and

damages

are set by

the

owner.

The

completion time must

be

reasonable

for

the

work,

and the

damages must also have

a

rea-

sonable basis. Unreasonable damages will likely

not

be

awarded

if

challenged

in

court

by the

contractor.

Reasonable damages

may

include additional engi-

neering

fees,

administrative costs, loss

of

revenue

to

be

generated

by the

project,

and fines or

penalties

assessed

by

another authority (such

as fines for a

vio-

lation

of the

National Pollution Discharge Elimina-

tion

Permit).

A

bid

bond

is

normally attached

to the bid

form.

Other attachments

often

include

bidders'

prequalifica-

tion data

and a

list

of

subcontractors. Examples

of

such

attachments

are

included

in the

EJCDC

and AIA

documents

[2,

3].

Bid

Bond

The bid

bond

may be

issued

by a

bonding company;

the

alternative

of

presenting

a

certified check

in the

amount

of the bid

bond

is

sometimes allowed.

The

purpose

of

this bond

is to

protect

the

owner

if an

apparent

low

bidder defaults

and

refuses

to

enter into

a

contract agreement.

The bid

bond

is

usually

10% of

the bid

price.

The

bonds

for the

three lowest bidders

are

held until

a

contract

is

awarded.

Contract

Agreement

This brief document

is the

legal instrument used

as the

formal

contract.

The

contracting parties,

the

time

frame

of the

work,

and the

amount

of

compensation

are

identified

or

established

in the

agreement, which

also incorporates

all of the

contract documents

by

ref-

erence (see

the

EJCDC

and AIA

documents

[2,

3]).

Performance

and

Payment

Bond

These bonds

are

provided

by the

contractor

from

a

surety

company

in the

amount

of

100%

of the

contract price

for

each bond. These bonds protect

the

owner

if the

contrac-

tor

fails

to

complete

the

work properly

or if the

contrac-

tor

fails

to pay

those

who

worked

on the

project.

Examples

are

listed

in the

EJCDC documents

[2].

Notice

of

Award

The

selected bidder (usually

the low

bidder)

is

noti-

fied

in

writing that

his bid was

accepted,

and the

con-

tractor

is

given

a

specified time

to

present

the

necessary bonds, insurance,

and

executed contract

agreement

to the

owner.

An

example

of the

notice

of

award

is

given

in the

EJCDC documents

[2].

Notice

to

Proceed

Upon

review

and

acceptance

of the

contractor's

bonds, insurance,

and

agreement,

the

owner executes

the

agreement

and

provides written notice

for the

con-

tractor

to

begin work within

a

specified

time

and to

complete

the

work within

the

agreed completion time

(see

the

example

in the

EJCDC documents

[2]).

Change

Order

Form

Changes

in the

work, completion time,

and

contract

price

all

require

a

"change

order"

to the

contract.

A

specific

form

for

this purpose

is

sometimes used

as

part

of the

formal

contract documents.

It is

typical

to

add

attachments

in

which

any

changes

are

described

in

detail.

An

example

of a

change

of

order

form

is

contained

in the

EJCDC documents

[2].

General

Conditions

The

general conditions

are the

focal point

of the

con-

tractual

documents. Documents

and

terms

are

defined.

The

authority

of the

owner

and the

relationship

of the

engineer

and

construction observer

are

outlined

as

well

as

the

duties

and

obligations

of the

contractor.

("Con-

struction

observer"

or

"resident

project representative"

are

the

preferred terms because

the

words

"inspector"

or

"supervisor"

may

communicate

an

unintended

meaning

—

and

liability

—

to

the

courts.) Method

of

payment,

insurance requirements, project completion,

guarantee

of the

work,

and

methods

of

resolving

differ-

ences

are

examples

of the

content

of the

general condi-

tions.

The

standard general conditions

as

published

by

the

professional societies

are

commonly used

in

speci-

fications

(see examples

in the

EJCDC

and AIA

docu-

ments

[2,

3]).

All

other documents must

be

consistent

with

the

content

of

these general conditions.

Special

Conditions

Special conditions

are

used

to

add, expand,

or

alter

the

general conditions. Special conditions

are

normally

written

for a

project

and

incorporate requirements that

are

specific

to the

project. When

the

owner requires

his

or

her own

special conditions

be

used

in the

documents,

it

may be

necessary

to

have

an

attorney review both

the

general conditions

and the

special conditions

to

avoid

conflicts.

When altering

a set of

standard general condi-

tions, make

it

clear that

it is a

change

and

reference

the

section

to be

altered. Avoid intermixing technical speci-

fications

with

the

special conditions. Also avoid

the

ten-

dency

to

repeat special conditions

from

previous

project

specifications

—

a

common source

of

conflicting

requirements

or

unnecessary specifications.

Addenda

Addenda

are

either written

or

graphic instruments

issued

prior

to the bid

opening

to

clarify,

revise,

add

to, or

delete

from

the

original bidding documents

or

previous addenda. Like change orders, addenda

are

often

prepared

in a

special

format

that later becomes

part

of the

formal contract documents.

28-3. Technical Specifications

Technical specifications provide

a

detailed descrip-

tion

of the

scope

of

work, type

and

quality

of

materi-

als, performance

of

equipment

and

systems,

and the

level

of

workmanship expected

of the

contractor.

The

drawings, which

are

also part

of the

contract docu-

ments, must

be

coordinated with

the

technical

specifi-

cations. Drawings illustrate construction

and

provide

a

graphic means

of

showing

the

work

to be

done.

Specifications

should supplement,

but not

repeat,

the

information

shown

on the

drawings. Unless otherwise

stated, specifications normally take

precedence

over

the

drawings,

and if a

conflict

arises

the

specifications

govern.

The

greatest

difficulty

in

writing technical

specifi-

cations

is to

decide when

a

given item

is

adequately

described. Obviously, each

and

every move required

by

workers

in

carrying

out the

work cannot

be

described.

The

underlying presumption

is

that con-

tractors execute work

at a

level that

is

consistent with

their particular trade.

The

specifications

are not to

instruct carpenters, pipefitters, plumbers,

or

electri-

cians

in

their trades. Industry standards

of

practice,

however,

are

frequently referenced

as

part

of the

tech-

nical specifications. Building

codes,

electrical

codes,

plumbing

codes,

and so on are

typical

of

such stan-

dards

of

performance.

Pitfalls:

Who

Should

Write

and

Coordinate

the

Specifications?

Obviously,

one

person cannot write

all the

technical

specification

required

in a

pumping station project.

Such

projects

are

complex

—

sometimes

very

com-

plex

—

and

several disciplines

are

involved, among

them

civil, structural, architectural, electrical, instru-

mentation,

and so

forth.

Various specialties, such

as

acoustics, vibration, model study,

and so on, are

sometimes needed.

All

these disciplines

or

specialties

(and

more)

may be

involved

in

preparing technical

specifications

for a

project,

and

hence, various parts

of

the

specification must

be

written

by

those experienced

in

such

specialties.

A

key

issue

is: who

should coordinate

and

review

the

technical

specialists'

work? Uncoordinated speci-

fications

can

result

in

problems ranging

from

dupli-

cate

—

and

different

—

specifications

for a

topic

to a

subject

not

covered

at all

(because

the

specialists

assumed

someone else

was

writing

the

specification).

Usually,

the

project manager should

be

responsible

for

the

review

and

coordination

of the

technical speci-

fications.

However,

one

person physically cannot

manage

both

the

nontechnical

and

technical aspects

of

very

large, complex projects. Considerable time

is

required

to

examine

and

coordinate

the

design draw-

ings

and

specifications page

by

page.

The

task

requires

someone with experience

in all

aspects

of

design

or at

least with enough experience

to

know

where

the

interdisciplinary problems usually occur

and

to

know

how to

resolve

the

problems. Conse-

quently,

a

technical assistant project manager

or

chief

project

engineer

may be

required

to

review

and

coor-

dinate plans

and

specifications continuously during

the

project

and to

perform

final

review

at the end of

the

design period. Some large organizations have

a

department

of

specification writers

who

become very

skilled

at

this activity.

Problems such

as the

following

are

frequently

found

and

must

be

resolved:

•

Geotechnical specialists providing standard

or

"canned"

specifications that

do not

match

the

rec-

ommendations

of the

geotechnical report.

•

Mechanical

and

civil (sometimes

called

"process")

specifications

for

valves, pipe hanger spacings, pipe

pressure ratings, pressure test requirements, etc.

that

are

inconsistent.

•

Electrical wiring that does

not

match

the

require-

ments

of the

instruments.

•

Materials

for

corrosion control that

are

inconsistent,

e.g., stainless steel specified

by one

discipline while

galvanized

steel

is

specified

in the

same area

by

another discipline.

•

Specifications

for

packaged equipment (e.g.,

pumps,

compressors)

that

are not

coordinated with

instrumentation

and

control specifications

and

P&IDs.

The

inexperienced pumping station designer

may

think

such coordination

is

simple

and

easily resolved

by

a

day-long conference

of

each

of the

discipline

leaders

—

a

naive supposition.

Addressees

Technical

specifications must address

a

wide range

of

parties. Although

the

contractor

is the

primary audi-

ence,

the

technical specifications must also address

bidders, subcontractors, suppliers, manufacturers,

workers,

and the

construction observer.

Each technical section

is

used for:

•

Bidding

•

Product

and

material submittals, standard

of

qual-

ity,

and

acceptance

•

Product description, materials

of

construction,

and

performance

•

Product installation, start-up,

and

functional

dem-

onstration.

However,

the

design engineer writes

the

specifications

to the

contractor,

who

will sign

the

agreement with

the

owner. Subcontractors

are not

legal parties

to the

agreement. Consequently,

the

design engineer should

not

write specifications stating things such

as

"the

concrete contractor

shall

.

.

."

or

"the mechanical con-

tractor shall.

. .

"A

phrase

to be

used

carefully

is "by

others."

The

intent

of the

engineer,

for

example,

may

be to

tell

the

concrete subcontractor that

he

does

not

provide

the

monorail support beams. But, because

the

contract documents

are

addressed

to the

general con-

tractor

—

the

entity with whom

the

owner

has the

legal

relationship

—

the

actual

effect

is to

tell

the

general

contractor that

he

does

not

have

to

provide monorail

support

beams

at

all.

The

phrase

"by

others"

should

only

be

used

to

denote equipment

or

work that

is

being done under another

set of

contract documents.

Most projects involve

a

wide variety

of

trades,

products,

and

materials that

are

needed

to

complete

a

pumping

station. Such complexity requires

a

system-

atic approach

to

writing technical specifications.

The

systems

used

may be

developed

by an

engineering

firm,

by

the

owners (such

as

federal specifications),

or

by

technical

or

professional societies.

The

system

or

approach should

not be

confused

with

specification content.

The

system

is the

method

that

is

used

to

break

the

complex project into mean-

ingful

sections

or

parts. These parts

may

then

be

described

in

detail,

and

their relationship

to

other

parts

may

also

be

described.

An

excellent

system

of

logical divisions, which

is

widely accepted

in

archi-

tectural

and

engineering projects,

has

been developed

by

the AIA

[4].

A

similar approach

is

contained

in the

CSI

literature [5], which includes

a

more detailed

breakdown

into three parts:

(1)

general,

(2)

products,

and

(3)

execution.

The

content

of

each

of

these parts

is

further

described

in the CSI

format

for

writing

specifi-

cations.

28-4. Source

Material

Numerous

sources

of

information

are

available

for

specifying

an

element

of

work

or a

product

to be

incorporated

in the

work.

In

general these sources

are

as

follows:

•

Manufacturers

or

suppliers

of

products

and

materials

•

Regulatory requirements (such

as

building

and

plumbing

codes)

or

owner-required specifications

(such

as

federal

or

military specifications)

•

Professional

or

trade organizations that have

set

standards

for

material composition, performance,

and

product standards.

As

a

designer

or

specification writer,

you

will

encounter numerous representatives

of

equipment

and

materials. Most representatives will provide typical

specifications

for

their

products. Although such infor-

mation

is

very

useful

for

keeping informed

on the

cur-

rent competitive market,

be

cautious when using

a

representative's standard specifications.

The

product

may

meet

the

regulatory requirements

and the

trade

standards,

but it may

also contain elements placing

it

in

an

unnecessarily favorable bidding position that

excludes other acceptable products. Review several

such

specifications

and

then edit

or

rewrite

the

specifi-

cations

to

ensure

two or

more sources that would

be

acceptable

for the

application. Avoid specifying ele-

ments that

are not of

standard manufacture unless

there

is a

special reason

for

such

a

choice. Remember,

special items

may be

difficult

to

maintain

or

replace.

Regulatory requirements

affecting

the

work should

be

referenced

in

appropriate specification sections.

Although

the

various trades working

on a

project

may

be

required

by law to

perform work under

a

given

code,

it is

best

to

state this

fact

in the

general portion

of

the

specification.

Do not

attempt

to

repeat

or

para-

phrase such codes because that could lead

to

conflicts

and

misinterpretations.

There

are

numerous professional

or

trade organiza-

tions that have developed product

and

material stan-

dards

and

quality tests.

The

given trade

or

industry uses

these standards

as a

means

of

self-regulation. Many

have

become national standards that

are

often

recog-

nized

by

regulatory agencies.

The use of

such standards

is

commonplace

in

technical specifications. Materials

may

often

be

specified adequately

by

simply referenc-

ing

the

appropriate trade standards.

A

more complex

item, such

as a

valve,

may be

specified

by

reference

to

an

appropriate

AWWA

specification. However,

the

ref-

erence

alone

may not be

adequate because

the

refer-

enced standard usually

has

selection options that must

also

be

identified.

Thus, such

a

reference must also

identify

the

options allowed

by the

referenced standard.

The use of

standards

is

extremely important.

Unfortunately,

the

engineering industry

in

general

and

design engineers

in

particular

are all too

often

increas-

ingly

unfamiliar with standards such

as

ASTM

and

ANSI,

and the

inexperienced engineer has,

at

best,

a

superficial

knowledge

of

standards. Unfortunately,

it

is

also common

for the

design

or

specifying engineer

or

architect

to be

unfamiliar with these referenced

standards and, frequently,

not to

have read them

at

all.

Many

of

these referenced standards,

if

blindly incor-

porated into

a

project contract document

by

reference,

will drastically alter

the

relationship between

the

design engineer,

the

owner,

and the

general contractor.

Other referenced standards

may

require

the

design

engineer

to

take actions that

may be

unwanted. There-

fore,

read every part

of a

referenced standard carefully

and

thoughtfully

and

refer exactly

to

those portions

that

apply

to the

project (see Section

1-4).

Limitations

of

Published

Standards

Published standards provide

the

specifier

with conve-

nient means

for

incorporating recognized benchmarks

of

quality into

the

detailed

requirements

for

contractor

or

manufacturer performance. Most published stan-

dards

are the

product

of

countless hours

of

effort

pro-

vided

by

volunteers interested

in

improving their

industry.

Today,

after

legal decisions have caused

a re-

examination

of the

process, most (but

not

all) stan-

dards-setting organizations

use

balanced committees

(memberships representing manufacturers, users,

and

consultants

or

specifiers)

to

develop consensus docu-

ments. Once

a

document

has

been developed,

it is

then

published

for

public comment. Public comments

are

then

considered

by the

committee

and the

document

is

adjusted

if

necessary before

final

publication. Standards

organizations usually have

an

oversight process

to

ensure

the

documents contain

no

biased requirements

These

consensus documents

usually

provide

the

specifier

with sound advice

on the

basic requirements

for

a

product

and

options

for

enhanced quality

or for

alternative features appropriate

for

special applica-

tions.

Many standards contain options

for

quality

assurance reporting

and for

user-nominated require-

ments

for

construction options.

No

standard, however,

is

perfect.

It is

unlikely that

any

standard will

be

entirely applicable

to a

given application without some

modification.

Consequently,

it is

incumbent upon

the

specifier

to

read

and

understand every standard com-

pletely with

a

watchful

eye for any

deficiencies such

as

omissions, poor

or

weak practice,

or

inconsistency

with

other standards.

The

following shortcomings

are a

few

examples taken

from

commonly used standards.

•

Omission. Omission

of

requirements

for

surface

preparation

for

coatings,

film

thickness testing,

or

frequency

of

testing.

•

Poor practice. Allowing threaded joints

in

Schedule

30

pipe.

•

Inconsistency. Referencing

a

specification

at

odds

with

the

main body

of the

standard.

•

Weak

practice. Allowing excessive pipe hanger

spacing

that results

in

excessive pipe sag.

Many

other examples

can be

cited,

but the

message

is

clear.

Referenced

standards

must

be

read

completely

and

with

care

(1)

to

discover

and

correct omission,

contradictions,

weaknesses

and (2)

especially

to

ensure

conformance

with

the

objectives

of

each

project.

A

list

of

organizations publishing standard refer-

ences that

are

commonly used

in

specifications

is

given

in

Section

F-I.

Every specification writer should

have

access

to the

ASTM

Standards

[6] (in 66

vol-

umes,

revised annually),

the

AVFWft

Standards [7],

and

the AIA

MASTERSPEC

[8] (as

well

as the

other

references

listed

in

Section 28-7).

28-5.

Specifying

Quality

Five basic methods

are

used

to

specify

the

quality

of

products

or

materials:

•

Performance

•

Nonrestrictive (also

"or

equal")

•

Proprietary

•

Generic

•

Reference standards.

Occasionally, modifications

are

made

by

combining

two

or

more methods (see also Table

16-1).

Performance

Specification

The

performance specifications describe

the

functional

result

that

a

product must achieve without identifying

any

specific

material

or

product. This approach usually

places

the

burden

of

some design work

on the

contrac-

tor.

Acceptance

of the

product

may not be

ensured until

it

has

been demonstrated that

it can

perform

the

intended

function.

The

cost

for

such

a

specification

may

be

high because

the

contractor must include design

costs

as

well

as

costs

to

cover unforeseen problems

should

the

products

fail

to

perform

as

specified. Perfor-

mance specifications

are

more typically used

in

con-

junction with other methods

of

specifying

a

product.

Nonrestrictive

(or

Equal)

The

competitive bidding requirements

of

most gov-

ernmental

agencies have resulted

in an

approach

to

specifications

in

which

the

writer identifies

by

name

two

or

more products that meet

the

requirements

of

the

design. These names

are

followed

by the

words

"or

equal."

If a

contractor submits

a

product

from

another manufacturer,

the

item

is

evaluated against

those named

in the

specification.

The

engineer must

then determine whether

the

item

is

"equal."

Such

a

determination

is

somewhat subjective because

the

items

are not

expected

to be

identical. Thus,

the "or

equal"

specification

is

usually combined with

a

cer-

tain amount

of

performance

and

product description

information

(such

as a

listing

of the

salient features

of

each unit with particular regard

for

maintenance, life,

and

efficiency)

that aids both bidders

and

engineers

in

making

the "or

equal" decision

and

settling disputes.

The

evaluation should ensure that

all

specified perfor-

mance

and

quality objectives

are

being satisfied. This

approach

has

become

one of the

most common meth-

ods of

specifying

the

more complex products.

Federal requirements

for

naming

two

products

are

eased somewhat

by

Public

Law

97-117,

which

requires naming only

one

product

or

equal. However,

some

EPA

regions

and

some states

and

local govern-

ments still require naming

two or

more products,

so

investigate

the

local requirements.

Proprietary

In

proprietary specifications,

the

product

is

defined

by

name. However, only

one

product

is

allowed. Obvi-

ously,

there

is no

competitive

bid in

this approach.

When

a

design requires

the use of a

single source,

care must

be

taken

to

establish

a

reasonable price

for

the

product prior

to

bid.

The bid

form

is set up in a

manner that

discloses

the

value

of the

proprietary

item, thereby allowing

the

owner

to

check prices

and

ensure that

the

supplier

did not

take

unfair

advantage

of

the

noncompetitive situation.

Proprietary specifications

are

banned under laws

and

regulations governing public works projects

for

most

federal, state,

and

local government agencies.

However, under Public

Law

97-1

17,

Section 204(a)(6)

of

the

Federal Water Pollution Control

Act was

amended

to

permit

the

grantee

to use

single "brand

name

or

equal"

specifications.

But be

aware

of the

fol-

lowing

restrictions:

• PL

97-117

applies exclusively

to

projects

financed

under

the

Federal Water Pollution Control

Act (PL

92-500).

• The

permission

to use a

single brand name

may be

superseded

by the

provisions

of

state

and

local laws.

• To

qualify,

the

grantee (owner) must agree that

a

single-source specification

is

acceptable "when

[in

the

words

of the

law]

in the

judgment

of the

grantee,

it is

impractical

or

uneconomical

to

make

a

clear

and

accurate description

of the

technical

requirements.

..."

In

most instances,

an

engineer would

be

hard pressed

to

justify

an

exclusive specification

for the

equipment

commonly

found

in

municipal water

and

wastewater

pumping

stations.

Generic

(or

Descriptive)

The

generic specification requires

the

product

be

described

in

sufficient

detail using,

for

example, per-

formance,

materials, quality control,

and

tolerances

without naming

a

product.

To

have

a

basis

for the

specification,

the

specification writer must have iden-

tified

at

least

one or

more products that will meet

the

specification.

This type

of

specification

is

usually

lengthy

and

difficult

to

write

for

complex products.

It

also presents problems

in

evaluating

the

product sub-

mitted

for

approval

by the

contractor.

Reference

Standards

The use of

reference

or

industry standards

is one of the

most

common methods

of

specifying

materials

or

prod-

ucts.

As

mentioned

in

Section 28-4, referring

to a

stan-

dard

specification

may be

sufficient

for

single items.

Reference

standards

for

more complex items, such

as

valves,

require more description than

a

simple reference

because there

are

often

options that must

be

defined

in

order

to

complete

the

referenced specification.

Refer-

ence specifications tend

to be

limited

to

materials

of

construction

and

simple components. Such references,

however,

are

used extensively

to

describe

the

quality

of

more complex items. Thus, references

are

used

in

con-

junction

with

the

previously described methods.

Be

sure

to

read subsection "Limitations

of

Pub-

lished Standards"

in

Section 28-4 before using refer-

ence standards.

28-6.

Submittal

Requirements

The

specifications must maintain

a

certain level

of

qual-

ity

and

performance

in

addition

to

allowing competi-

tion

so

that

the

owner

can get the

best price.

The

determination

of

acceptable products

and

materials

is

often

difficult

and

controversial.

One

method

of

han-

dling

this situation

is to

require

the

prequalification

of

manufacturers.

Prequalification adds

an

extra step

to

the

bidding process

but

provides

a

very good method

of

controlling

the

quality

of the

products. This approach

also eliminates controversy during

and

after

bidding.

The

more common acceptance method

is

through

the

shop-drawing procedure.

Prequalifications

do not

eliminate

the

shop-drawing step. Generally,

the

shop-

drawing review

is

used

to

ensure that

the

details

of the

specifications

are

being followed. This review

may

also

be

used

as a

basis

for

rejecting

the

entire product

as

submitted

by the

contractor. Complete rejection

of

a

product

at the

shop-drawing-review stage

can

create

scheduling

and financial

problems

for a

contractor,

particularly

if the

products

are a

major

portion

of the

contract.

The

specification should

identify

products

adequately

so

that contract bids

are not

based

on

unac-

ceptable products that must

be

rejected.

In

addition

to

shop-drawing reviews, other quality-

control tests

and

certifications

may be

required. These

controls represent another method

of

checking prod-

uct

quality.

Use

care

in

warranty requirements,

because unreasonable requirements unnecessarily

increase prices.

28-7.

References

1. CSI

Document

MP-I,

The

Construction Specifications

Institute,

Alexandria,

VA:

Document

MP-

1-1,

"Construction

Documents

and the

Project

Manual"

(1996).

Document

MP-1-2,

"Bidding

Requirements"

(1996).

Document

MP-1-3,

"Types

of

Bidding

and

Contracts"

(1996).

Document

MP-1-4,

"The

Agreement"

(1996).

Document

MP-1-5,

"Conditions

of the

Contract"

(1996).

Document

MP-

1-6,

"Division

1,

General

Requirements"

(1996).

Document

MP-

1-7,

"Relating

Drawings

and

Specifications"

(1996).

Document

MP-

1-8,

"Changes

to

Bidding

and

Contract

Documents"

(1996).

Document

MP-

1-9,

"Specification

Writing

and

Production"

(1996).

Document

MP-1-10,

"Specification

Language"

(1996).

Document

MP-1-1

1,

"Methods

of

Specifying"

(1996).

Document

MP-1-12,

"Performance

Specifications"

(1996).

Document

MP-1-13,

"Procurement

Specifying"

(1996).

Document

MP-

1-14,

"Civil

Engineering

Applications"

(1996).

Document

MP-

1-15,

"Mechanical

and

Electrical

Engineering

Applications"

(1996).

Document

MP-

1-16,

"Preparation

and Use of an

Office

Master

Specification"

(1996).

2.

EJCDC,

Engineers'

Joint

Contract

Documents

Committee,

The

Construction

Specifications

Institute

(CSI),

Alexandria,

VA:

Document

No.

1910-8,

"Standard

General

Conditions

of the

Construction

Contract"

(1996).

Document

No.

1910-8-A-l,

"Standard

Form

of

Agreement

between

Owner

and

Contractor

on the

Basis

of a

Stipulated

Price"

(1996).