Ripper J. American Stories: Living American History. Volume 2: From 1865

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

AMERICAN CULTURE AND SOCIETY

12

American Culture and Society in

the 1950s and 1960s

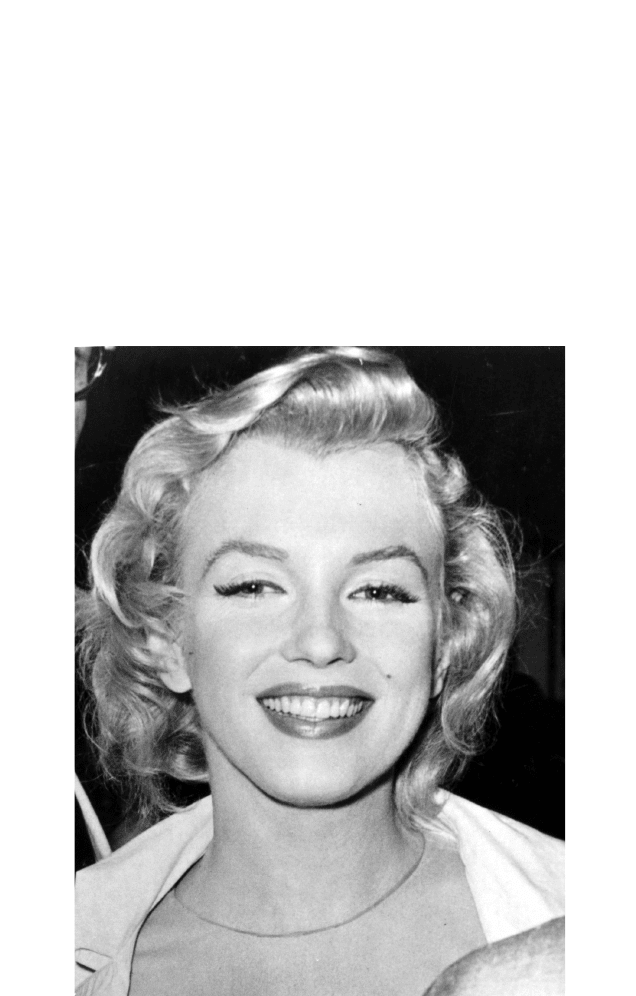

Marilyn Monroe (Evening Standard/Getty Images)

219

AMERICAN STORIES

220

White and Black, Apart and Together

With the war won and the boys coming home, people wanted to enjoy the

peace. Prosperity seemed like the best reward possible, and by 1950 a brief

postwar recession had been sorted out. Suburban subdivisions sprouted,

providing jobs for the builders, the bankers and lenders, the loggers felling

the trees to turn into lumber delivered from forest to sawmill to subdivision

by truckers on new interstate highways funded by the federal government.

After four years of government rationing, Americans bought big cars moved

by high-compression engines, gulped Pepsi or Coke and munched popcorn

at sprawling drive-ins featuring two or even three movie screens, purchased

television sets at the rate of more than 1 million a year, and butter-knifed

through the salty Salisbury steaks of a Swanson TV dinner. Women hosted

Tupperware parties. Dads came home from work to throw a ball with the kids

and help with the homework. There was time to work and time to play.

As had always been the case, peace and prosperity for some did not mean

peace and prosperity for all. After witnessing the lack of segregation in Europe

and the Pacific, African-American soldiers returned to a segregated America.

Lynching continued in the South. Schools for black children remained second-

rate. White men still called grown black men “boy.” And in the deep south of

Mississippi, it was dangerous for a black man or teenager to look at a white

woman, except from the corner of a downward-turned eye. Stepping outside

the boundaries was a bad idea.

Emmett

Till, a fourteen-year-old from Chicago vacationing at his uncle

Moses Wright’s place in Mississippi, stepped outside the race boundary.

Inside a drugstore, Till apparently flirted with a white woman, Carolyn Bry-

ant,

maybe by whistling, maybe by calling her “baby.” Four nights later, on

August 28, 1955, two white men—the woman’s husband, Roy, and his friend,

J.W. Milam—took a sleeping Emmett Till from a bed at his uncle’s house

and, equipped with pistols and a flashlight, drove for hours, looking for the

right spot to “scare some sense into him,” as the men admitted a year later in

a Look magazine article.

1

They pistol-whipped Till in the face and head with

a Colt .45 so severely his skull bones turned to mush. They castrated him,

shot him through the ear, and then sank his body under water with a giant

metal fan tied to his neck, satisfied that they had done the right thing. Less

than a month later, with the whole nation following the case, an all-white

jury acquitted Bryant and Milam in sixty-seven minutes, one jury member

saying it would have taken less time but they had slowed down to sip a soda.

The killers lived until 1990 and 1980, respectively, shunned but free. Emmett

Till’s mother held an open-casket funeral for her mangled son in Chicago,

and a stunned nation reacted in outrage. But there were also letters to editors

221

AMERICAN CULTURE AND SOCIETY

of various newspapers expressing support for Bryant and Milam. Changing

southern culture would take a revolution.

In

Montgomery, Alabama, three months after Emmett Till’s grisly murder,

Rosa Parks, a seamstress and secretary for the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), refused to give up her bus seat to

a white man, got arrested, and sparked a year-long bus boycott that generated

enthusiasm for the burgeoning civil rights movement, which had been run for

decades by the NAACP largely through lawsuits.

In 1954, one year before both Emmett Till’s fateful trip to Mississippi

and Rosa Parks’s brave defiance of social custom, the Supreme Court had

ruled unanimously in Brown v. Board of Education that racial segregation

was unconstitutional and did not provide “separate but equal” treatment

for blacks and whites, as many whites had been claiming for fifty years

ever since Plessy v. Ferguson. However, in a follow-up ruling in 1955, the

Supreme Court said that with regard to implementing the new policy of

integration, district courts could give “such orders and decrees consistent

with this opinion [in Brown] as are necessary and proper to admit to public

schools on a racially nondiscriminatory basis with all deliberate speed the

parties to these cases.”

2

The key phrase was “with all deliberate speed.”

School districts could, in other words, integrate very slowly if they chose

(and white people could move to the suburbs and continue putting their

children into mainly homogeneous schools). Still, a reversal had been made,

and the federal government now aligned itself—even if cautiously—with

the hopes of African-Americans like Thurgood Marshall, who had argued

the Brown case, and Martin Luther King Jr.

While Thurgood Marshall’s very public role in the Brown case helped him

to become the first African-American member of the U.S. Supreme Court (in

1967), the Montgomery bus boycott elevated a young Baptist minister, Mar-

tin

Luther King Jr., to prominence and gave him a platform to demonstrate

the effectiveness of nonviolent activism and protest. In fact, during the long

bus boycott, King’s house had been firebombed—with his wife, Coretta,

and baby daughter at home—and he had been arrested. But King remained

publicly calm and strong, if anything growing more resolute in the face of

hostility, learning how to cast his voice through the storm. Not since the

days of Booker T. Washington and Marcus Garvey had there been a black

man with King’s emerging popularity. With a warm-honey voice, a Baptist

preacher’s rise-and-fall, hush-then-hurry rhythm, and a dignified message,

Martin Luther King Jr. was the kind of man who could inspire a revolution,

the kind of man who could make other people want to do good. Race bigots

were watching their rule, their privileges, their arguments fall before a slowly

building wave of justice.

AMERICAN STORIES

222

While northern suburbs passed covenants barring black people from buying

a home and southern juries propped up the sad sight of Jim Crow, black Ameri-

c

ans bonded together with white allies to challenge the laws, the customs, and

the attitudes that perpetuated oppression. When Thurgood Marshall had argued

the Br

own case during the early 1950s, his staunchest supporter on the bench

had initially been Felix Frankfurter, who had known how to slow down the

judicial process long enough to rally the other justices. After President Dwight

D. Eisenhower appointed Earl Warren chief justice in 1953 (while the Brown

decision

was pending), he put his considerable political skills to the task and

wrangled a unanimous ruling in Brown by getting hesitant fellow judges to see

the moral value in a united court opinion. When Martin Luther King Jr. formed

the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957, sixty black

ministers joined him in a pledge of nonviolent direct action for change. Their

peaceable tactics soon attracted white allies from north and south. In 1960,

four black college students in Greensboro, North Carolina, staged a sit-in at

a segregated Woolworth’s department store lunch counter. Within a few days,

three white co-eds (as female college students were called in the 1950s) from

the Women’s College of the University of North Carolina had joined their

growing ranks. By year’s end, more than 50,000 people—well-dressed and

polite—had participated in similar sit-ins across the South and North, with

ever more white volunteers joining the young black men and women sitting

quietly at counters for burgers or sodas fifty years in the coming. In April 1960,

a coalition of black and white students, inspired by the SCLC’s adherence

to nonviolence and by the ongoing integration sits-ins, formed a new civil

rights organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC,

pronounced “snick”). Then, when the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE)

organized “freedom rides” on interstate buses in 1961 to speed integration of

public transportation, the freedom riders were white and black, and they bled

together when members of the Ku Klux Klan and various other goons pulled

them off their buses in Alabama and beat them savagely.

To say you were nonviolent was one thing, but to let another person hit you,

kick you, trample you, required the fastening of your soul to a greater purpose.

Once when Martin Luther King Jr. was giving a speech on stage, a man ran

up and punched him three times in the face. When audience members rushed

to King’s aid, he asked them not only to leave the assailant untouched but

also to pray for him. Sometimes, at night in the privacy of his kitchen, King

would tremble with visions of his death. But on the dais or the street talking

to the milling crowds, King radiated calm, slow courage. He mingled with

the members of his congregation and with prime ministers and presidents.

They had to meet him. King was their future.

F

rom the presidential perch, Harry S. Truman watched African-American

223

AMERICAN CULTURE AND SOCIETY

baseball star Jackie Robinson swat his way out of the Negro Leagues and

into a major league ballpark in 1947 when he debuted with the Brooklyn

Dodgers. Other sectors of the business world also started to open doors.

With an eye for progressive profits earned fairly and decently, the Pepsi-

Cola Company, under its president, Walter Mack, promoted its products by

hiring and training the first African-American sales team in a major U.S.

corporation. Sales skyrocketed in black communities and an example was

established for integration via the business corridor, though most of the

fanfare showed up in black-owned newspapers.

3

Although Truman was

not able to get a hemming and hawing Congress to pass his proposed civil

rights initiatives, he did order the armed forces to integrate and mandated

that civilian agencies attached to the federal government would have to enact

fair employment standards. While Truman acted openly without prompting,

President Eisenhower supported civil rights when nudged. Eisenhower took

Truman’s military integration order and made it happen. He had, after all,

been the nation’s premier war hero—who better to change military culture?

After the Supreme Court overturned “separate but equal” segregation, nine

black students in Little Rock, Arkansas, tried to enroll at Central High

School, but Governor Orval Faubus ordered the state national guard and

state police to surround the school and prevent the “Little Rock Nine” from

entering. Eisenhower sent in the 101st Airborne, federalized the National

Guard, and provided bodyguards for the black students, one of whom gradu-

a

ted at the end of the year (after which, Governor Faubus shut down all the

schools in Little Rock). However, Eisenhower was reluctant to use the courts

or legislation to promote racial equality. He believed laws would not change

“the hearts of men.” King, on the other hand, said, “A law may not make a

man love me, but it can stop him from lynching me.”

4

Nonetheless, despite

the president’s stalling, Congress passed the 1957 Civil Rights Act (which

was shuttled through the Senate by a war veteran from Texas named Lyndon

Baines Johnson, the youngest-ever Senate majority leader).

Although most Americans tried to sink into a quiet peace, in many ways

World War II had made America ripe for social revolution. The nation had

fought Hitler’s obvious racism. Black men had once more worn a military

uniform, and some of their white brothers in arms were willing to join the civil

rights cause. In Florida, for example, when a bus driver told a black veteran to

either move to the back of the bus or get off, the man’s fellow veterans, both

white, told the driver to mind his business and drive or they would throw him

off and drive the bus themselves. A growing segment of Americans demanded

that peace and prosperity should be made equally possible for all citizens.

The struggle expanded in the mid-1950s and grew to a crescendo during the

1960s, leading to the legal dismantlement of Jim Crow segregation.

AMERICAN STORIES

224

Rebels in Denim and Diamonds, and Rebels with a Pen

Somehow the popular imagination sees the 1950s and early 1960s as a time

of square-top haircuts, gentle manners, safe neighborhoods, and cold milk

before bed. The buzz cuts and barbecues were real and ubiquitous, but for

every half-gallon jug of milk left on a doorstep there was a rowdy teenage boy

greasing his hair, rolling up the cuffs of his coal-blue jeans, and daydreaming

about drag racing toward a drop-off cliff, just like James Dean did in Rebel

W

ithout a Cause (1955). For every malt milkshake or Coca-Cola served by a

freckly soda jerk at the local drug store or soda fountain there was a cold beer

served to a war veteran at the local American Legion or to a down-and-out

alcoholic at the local dive or to a two-wheeled loner wearing “black denim

trousers and motorcycle boots”

5

—like Willie Forkner, the real-life inspiration

for another era-defining film, The Wild One (1953), starring Marlon Brando, a

cool hunk first made famous for his steamy performance in the movie adapta-

tion

of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire (1951). In July 1947,

Willie Forkner and some vet buddies—part of the Boozefighters motorcycle

club, whose motto was “A drinking club with a motorcycle problem”—rode

their cycles into Hollister, California, triggering two nights of brawls with

townspeople who did not like the bikers parking their rides indoors in the

quiet off-hours between incessant street races. Years down the road, Forkner

remembered feeling bitter about the way he had been treated after serving in

World War II: “We were rebelling against the establishment, for Chrissakes.

. . . You go fight a goddamn war, and the minute you get back and take off

the uniform and put on Levi’s and leather jackets, they call you an asshole.”

6

The 1950s were anything but simple, and emerging music genres gave voice

and melody to the itch that people were feeling.

Country

music rambled at the Grand Ole Opry, and delta blues slid and

wailed in the backwaters of Louisiana and Mississippi. Someone somewhere

on one guitar was bound to introduce country music to the blues. In 1954,

a shy, polite, pimple-faced, blue-collar boy from East Tupelo, Mississippi,

stopped off at Sam Phillips’s Sun Records studio near Memphis, Tennessee,

and recorded a few little ditties that he claimed were for his mama. But re-

ally

Elvis Aaron Presley wanted to hear how his voice sounded on a record.

Before long, Elvis’s hips were gyrating from one dance hall to the next while

“Jail House Rock” blasted out of every radio and turntable from East Tupelo

to Tacoma.

Parents who worried about the “race record” sound of Elvis’s electrified

rock ’n’ roll could take their teenagers to see comforting movies starring

safe-joke Bob Hope, who had long since made a name for himself in goofball

comedies and by entertaining troops as part of the United Service Organiza-

225

AMERICAN CULTURE AND SOCIETY

tions (USO). The same Hollywood producers and directors who sponged mil-

lions from Hope’s clean-cut comedy also squeezed green from another USO

performer, Norma Jean Mortenson, who dyed her hair blonde and changed

her name to Marilyn Monroe. Monroe winked, teased, pouted, and purred in

sexy, irreverent films like The Seven Year Itch (1955) and Bus Stop (1956).

Elysian Marilyn Monroe, antiauthoritarian Marlon Brando, and teen-dream

James Dean delivered equal doses of sexy, rebellious, and dangerous. Tough

guys wore jeans and diamonds were a girl’s best friend.

Monroe’s movies and Presley’s songs gave something essential to a gen-

eration

taught at school by a cartoon turtle to “duck and cover” if they saw a

bright flash of (atomic) light. A poet-musician named John Trudell put it best

when he sang that Elvis was a “Baby Boom Che,” a revolutionary fighting “a

different civil war” against a culture of “restrained emotion” with the help of

Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Bo Diddley, Elvis’s “commandants.” Trudell

grew up during the 1950s, and like a lot of other kids who would go on in the

1960s to challenge the status quo (which he did after serving in Vietnam),

he thinks Elvis “raised our voice, and when we heard ourselves, something

was changing.”

7

Part of what was changing during the 1950s was the public

attitude toward sex and sexuality. The closeted restraint of the old Comstock

laws would not last much longer.

While major magazines, daytime television soap operas, and nighttime

favorites like The Honeymooners and I Love Lucy encouraged women to drop

their welding aprons and put on kitchen aprons, the first issue of Playboy

magazine

was issued in December 1953. Marilyn Monroe graced the cover

smiling and waving in a slinky, v-cut black dress; she also graced the centerfold

dressed casually in her birthday suit; and Playboy’s founder, Hugh Hefner,

joked

that the magazine would provide “a little diversion from the anxieties

of the Atomic Age.” After all, Hefner wrote, frisky men enjoyed “putting a

little mood music on the phonograph and inviting a female acquaintance for

a quiet discussion on Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex.”

T

he contrast between Playboy’s nudity and network TV’s modesty

highlighted the schizophrenic three-way divide in 1950s America between

puritanical timidity, playful titillation, and outright sexual extravagance, as

exemplified in Alfred Kinsey’s reports, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male

(

1948) and Sexual Behavior in the Human Female (1953). Both were best

sellers that exposed in the frankest of terms that about 75 percent of people

interviewed had had premarital sex, almost all men masturbated, and about

one-third of men had had at least one homosexual experience ending in

orgasm—this at the same time that the State Department proudly proclaimed

that once each day it was firing a homosexual, part of the “Lavender Scare”

that falsely conflated homosexuality with communism and anti-Americanism.

AMERICAN STORIES

226

If one-third of American men kissed and touched other men, homosexuality

was, as Kinsey insinuated, quite American. As for marital fidelity, Kinsey

reported that about 50 percent of men cheated, as did nearly 34 percent of

women. And well-to-do businessmen cheated more than anyone else, more

than 75 percent having strayed at least once. Although Kinsey’s percentages

have since been questioned, his reports completely altered American percep-

t

ions of sexuality by making it a topic fit for public consumption, by allowing

for recognition of women’s equal right to orgasm, by generating sympathy

for homosexuals in a very homophobic society, and by suggesting that sexual

orientation was fluid rather than fixed. Television shows featuring families

rarely showed bedrooms, and when they did, mom and dad slept in separate

beds—a not terribly accurate portrayal of American family life considering

the 76 million babies born from 1946 to 1964. Ward and June Cleaver had

to conceive the Beaver somewhere; maybe they went to the drive-in. As one

interviewee in the 2006 documentary Drive-in Movie Memories recalled,

“Many lives were caused by accident last night.”

8

Henry Ford’s lamentations about the amorous use of his Model T were more

on-target than ever after World War II when automakers could stop making

army jeeps and start making cars again. In 1950 alone, Americans bought 6

million cars. By 1953 almost two-thirds of Americans owned a car; 40 percent

of women had a driver’s license.

9

General Motors, under the direction of Al-

fred P. Sloan, made and sold nearly one-half of all automobiles, and Sloan’s

deputy, Harley Earl, innovated the yearly release of a new model, ensuring

better sales for carmakers by encouraging customers to “keep up with the

Joneses” who sported the latest Cadillac. This was conspicuous consumption

taken to a new level where social status derived not from family history, good

deeds, or academic degrees but from make and model. Advertisers provided

the outline, and Americans bought the image. From his corporate perch Har-

ley

Earl himself emphasized the central role of image: his office closet was

stocked with a ready supply of outrageously colorful suits, and since he would

not let his son drive a Ferrari, he ordered the design department at General

Motors to whip out a one-of-a-kind Corvette to keep the young man happy,

hip, and inside the brand.

Cars

needed roads, so the federal government paid for an asphalt flood of

road and highway construction. President Eisenhower’s 1956 Federal-Aid

Highway Act created the interstate highway system—free of tolls. The last

and full transformation of America into the world’s premier car country was

under way. Not only did this nation with a mere 6 percent of Earth’s popula-

tion

own two-thirds of the world’s cars,

10

but Americans were driving their

tail-finned Ford Fairlanes and cherry-red Chevrolet Corvettes to and from the

spreading suburbs as quickly as men like William Levitt could get them built.

227

AMERICAN CULTURE AND SOCIETY

The cars were flashy; the suburbs were functional. And anybody who wanted

to be middle-class and could afford the entrance fee packed up and headed

for suburbia. By 1960, half of all Americans lived in the suburbs.

Barbie in the Suburbs

William Levitt came from a contractor’s family and was a Navy Seabee in

the Pacific theater during World War II, ironing out instant landing strips in

malarial jungles and watching fellow Seabees building Quonset huts and bar-

r

acks efficiently and sturdily. With a sense for mass production of housing and

communities, Levitt returned to the States and set about designing a town of

tiny, identical two-bedroom houses with no basements, whitewashed picket

fences out front, and a red-brick chimney poking up from every roof. Just as

Henry Ford had placed one worker doing one task in one spot on one factory

floor all day long, Levitt hired single-job men who monotonously banged on

the siding, painted the windowsills, or ratcheted in the washing machines.

Before long, the first Levittown—on Long Island, NY—had 17,000 houses.

To outsiders, the uniformity seemed stultifying. To homebuyers, the sameness

was either irrelevant or comforting. Levitt’s houses sold for an affordable

$8,000, and for war veterans, the GI Bill furnished the down payment. By

1950 nearly 30 percent of Americans lived in suburbs.

Immediately after the war, the national housing shortage was so acute that

veterans were sleeping in government-donated Quonset huts, in rented-out

railroad cars, and in their parents’ basements. But at Levittown, every new

family got not only immediate entry into the independence of middle-class

living but also a free television on which Michael and Mary (the most popular

boy and girl names in 1955) could watch fourteen-year-old Annette Funicello

singing “M-i-c k-e-y M-o-u-s-e” as one of The Mickey Mouse Club’s original

Mouseketeers. Walt Disney had been making movies for twenty years; Disney

World—a one-stop subdivision for cartoon characters come to life—opened

in Florida in 1954, giving outwardly conformist suburbanites a common

destination for a prefabricated vacation. Before long, Disney World visitors

could stay in nearby Holiday Inns, first opened in the early 1950s, and eat

fifteen-cent hamburgers at a franchised McDonalds. Family destinations were

starting to look alike no matter where the average family of five went. And

just like the ubiquitous “Mary” at home watching The Mickey Mouse Club,

child

star Annette Funicello wore a cotton sweater and bobby socks, attended

school, and was expected to be polite and cheery. Unlike Michael and Mary,

Annette had on mouse ears . . . but the family could pick up a couple of pairs

on their trip to Disney World.

More than ever before in American history, corporate products, logos, ad-