Ripper J. American Stories: Living American History. Volume 2: From 1865

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

IN LOVE AND WAR: 1961–1969

13

In Love and War: 1961–1969

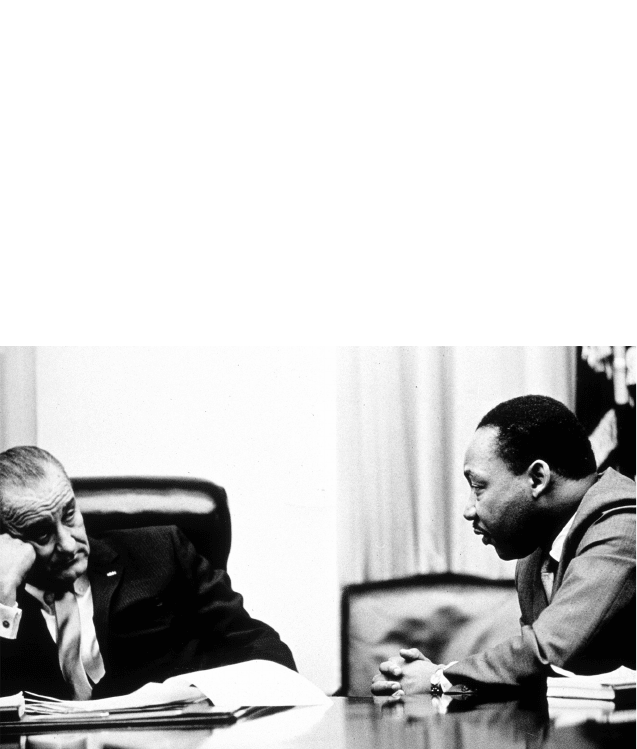

Lyndon B. Johnson (left) and Martin Luther King Jr. (right)

(Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

239

AMERICAN STORIES

240

Big Dreams

On November 8, 1966, people whose television sets were tuned to NBC

launched themselves into outer space along with Captain Kirk, Mr. Spock,

Lieutenant Uhura, Bones (the doctor), and all the rest of the crew of the star-

ship Enterprise, “its five-year mission . . . to boldly go where no man has

gone

before.” Enter angelic voices “ooh-oohing” at the stars. Cut to the flash

of light from the twin propulsion systems of the USS Enterprise as it winks

out of sight, bound for a beautiful future somewhere far, far away. Star Trek

was written by Gene Roddenberry

, but it was created by the 1960s.

Theoretically, everyone in the United States was aboard the beeping and

flashing deck of the Enterprise. With America deep in the midst of its own

shame

and glory—with the Vietnam War heating up, President John F. Ken-

n

edy three years dead of an assassin’s bullets, civil rights leaders divided over

methods of peace and violence, homosexuals stepping out into public and

proclaiming pride, Native Americans and Latino-Americans demonstrating

for their rights—maybe it took an interracial, interplanetary crew blasting

away from all the craziness on Earth to give proper perspective to the best

parts of the American Dream.

In 1962, Kennedy had challenged the nation to put a man on the moon.

But with the Apollo space program mired in problems—including a January

1967 flash fire that killed a flight crew during a routine on-ground training

mission—the starship Enterprise seemed to be the collective fantasy needed

to keep spirits high.

W

ith equally lofty ambition, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil

Rights Act (which Kennedy had proposed) in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act

in 1965—both monumental in their pledge of federal support for civil rights

that had been till then no more substantial than thin dried ink. Although both

the space program and the civil rights program faced monumental challenges,

racism proved a more stubborn foe than the difficulties of extraterrestrial rock-

etry

. In 1964, in Selma, Alabama, only 2 percent of African-Americans were

able to register for the vote. Regardless of new laws, many white southerners

continued to resist integration and other forms of equality in despicable, ugly

ways. During the “Freedom Summer” of 1964, when civil rights workers,

including hundreds of primarily white college students from the North, con-

v

erged in Mississippi to register African-Americans to vote, violence engulfed

the region. Most memorably, two northern whites—Michael Schwerner and

Andrew Goodman—and one black man from Mississippi, James Chaney,

were kidnapped by Ku Klux Klansmen, tortured, murdered, and buried. A

visiting physician who examined Chaney’s recovered corpse said that in his

long career he had never seen a body as badly ruined as Chaney’s except when

241

IN LOVE AND WAR: 1961–1969

corpses had been pulled from car or airplane crashes. And at the Democratic

National Convention that year, when delegates from the new, 60,000-strong

Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) tried to participate, white

southern Democrats laid down an ultimatum that amounted to racist blackmail:

either the MFDP delegates would be ignored or segregationist Democrats

would leave the party and thereby steal President Johnson’s base in Congress.

The MFDP was composed of African-Americans who had registered during

Freedom Summer, and now their own nominal parent organization refused to

seat them. With television cameras rolling, a sharecropper and descendant of

slaves named Fannie Lou Hamer sat at a table in the convention hall and told

how she had been driven off her land in 1962 after daring to register and how

she had later been arrested (essentially for being black) after attending a civil

rights workshop. The arresting officer kicked her in the stomach before shoving

her into a patrol car and then into a jail cell. Then, Hamer recounted:

[I]t wasn’t too long before three white men came to my cell. One of these

men was a State Highway Patrolman and he . . . said, “We’re going to make

you wish you was dead.”

I was carried out of that cell into another cell where they had two Negro

prisoners. The State Highway Patrolman ordered the first Negro to take the

blackjack. The first Negro prisoner ordered me, by orders from the State

Highway Patrolman, for me to lay down on a bunk bed on my face. And I

laid on my face, the first Negro began to beat me.

And I was beat by the first Negro until he was exhausted. I was holding

my hands behind me at that time on my left side, because I suffered from

polio when I was six years old.

After the first Negro had beat until he was exhausted, the State Highway

Patrolman ordered the second Negro to take the blackjack.

The second Negro began to beat and . . . I began to scream and one white

man got up and began to beat me in my head and tell me to hush.

One white man, my dress had worked up high, he walked over and pulled

my dress—I pulled my dress down and he pulled my dress back up . . .

All of this is on account of we want to register, to become first-class

citizens. And if the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question

America. Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave,

where we have to sleep with our telephones off of the hooks because our

lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings,

in America?

1

History and tradition still had the South by the throat. But out in space, in a

future cut loose from the past, no federal laws or marshals were there to stop

the first interracial kiss in television history between Kirk and Uhura—he the

AMERICAN STORIES

242

white captain, she the black communications officer. That is what stories are

for sometimes: to show us who we can be.

Then

there was the “prime directive” handed down to the space trekkers

aboard the Enterprise. Whenever they encountered an alien civilization, Kirk

and

crew were instructed not to unduly interfere, not to introduce advanced

technologies that might alter or even ruin a thriving and ancient culture. The

Enterprise crewmembers could fire their photon torpedoes and lay down

a barrage of laser beam fire when necessary, but their best moments came

from diplomacy and negotiated respect with whatever planet full of wrinkly

faced humanoids they found. This grander purpose of peace was a modern

allegory. The crew of the Enterprise could escape Earth but they could not

escape

being human. Wherever they went, conflict waited for them. And just

about every species had the same capacity to kill. This was the Cold War in

space. Gene Roddenberry, having fun all the way, was doing his best to raise

people’s consciousness.

By June 1969, when the last of the eighty episodes aired, Star Trek’s

universal popularity had spread through the living-room temples of Trek-

kies

implanted like alien invaders in every town and city. Trekkies looked

like normal people, but they wanted to speak Klingon and plot a utopian

revolution of logic, reason, and pointy ears—all inspired by a low-budget

show with props that looked more like wobbly cardboard than space metal.

The dream was what mattered. Besides, reality was catching up with fiction:

six months earlier, three American astronauts on Apollo 8 had been in and

out of a moon orbit, and July 20, 1969, was only a month away, when Neil

Armstrong would set his white boot onto the powdery surface of the moon

and proclaim, “That’s one small step for man; one giant leap for mankind.”

Humans really were star trekking, and it seemed that Spock’s extraterrestrial

Vulcan salutations, “Live long and prosper” and “Peace and long life,” might

really come true. In mid-August, on Max Yasgur’s farm in Woodstock, New

York, young people gathered to bask in the beat of Janis Joplin’s wail, Joan

Baez’s folk, the Grateful Dead’s transcendent space riffs, and Jimi Hendrix’s

guitar licks. On a mere 600 acres, about 400,000 tripped-out freaks, sober

collegians, and other happy fans waded through rain and mud, smoked bushels

of pot, and coexisted peacefully with the neighboring farmers who helped

feed and water the legions of love. If humans could tear free from gravity and

soar some 238,000 thousand miles away, the thinking went, surely poverty,

inequality, and strife could be overcome.

As in space, so on earth: at solemn moments of goodbye, Leonard Nimoy’s

character Spock flashed the Vulcan salute, a kind of spaceman’s peace sign and

handshake in one, his whole hand turned into a V; flower children—the baby

boomer college kids who wanted to “make love, not war”—flashed their own

243

IN LOVE AND WAR: 1961–1969

two-fingered V for peace at cameras, cops, and each other. The V-for-peace

became so common that Robert F. Kennedy, John F. Kennedy’s younger brother,

used it during his 1968 presidential campaign on the night he told a mostly black

audience in Indianapolis that Martin Luther King Jr. had been shot to death by a

white man. Kennedy cautioned calm, expressed his grief, and shared a line from

an ancient Greek playwright. “My favorite poet,” he said into the microphone,

“was Aeschylus. He once wrote: ‘Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget

falls drop by drop upon the heart, until, in our own despair, against our will,

comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.’”

2

He then offered the peace

sign in parting. The “Establishment” was being co-opted by the counterculture,

and the crowd in Indianapolis did stay calm even as rioting engulfed other cities

throughout the nation. There was reason to hope.

Gene Roddenberry’s vision of a harmonized human future squared with the

mystic awe felt by television viewers when Apollo 8 astronauts beamed back

narrated color photos of Earthrise over the moon’s horizon. In the vastness

of dark space, Earth floated blue, a minuscule ball of color and life bobbing

in the abyss. The perspective of distance made people feel close. The Soviets

posted congratulations to America in a state-run newspaper right after Apollo

8 made its splashy return into the Pacific. Maybe even Cold War competition

could be healthy and dif

ferences bridged.

But in 1968, two months after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination,

Robert Kennedy also was gunned down, right after winning the California

presidential primary on a platform dedicated to social justice and peace. En-

tropy

, anger, and fear were trying to strangle love and hope. As Kennedy’s

funeral train chugged eastward, tens of thousands of mourners spontaneously

gathered along the tracks, holding signs proclaiming, “Bobby, we love you.”

In Vietnam in January 1968, during the Vietnamese lunar New Year, Tet,

communist forces attacked more than 100 sites and installations across the

country (including the U.S. embassy), shocking the public into a realization

that the United States most definitely was not about to “win” in Vietnam, as

the administration and military leaders had been saying for three years. In

Chicago, riots erupted between demonstrators and Mayor Richard Daley’s

police squads during the Democratic National Convention. Daley had more

than 6,000 police and federal army troops at his disposal, including about

1,000 operatives from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Once more, but not for the last time,

men with badges and clubs battered unarmed demonstrators. The whole na-

tion

watched on television in stunned disbelief. Faith and trust seemed to be

leaking away. Good people kept dying, and the goodness they invoked in the

hearts of a confused nation started to seem as impossibly distant as the alien

civilizations Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock had visited.

AMERICAN STORIES

244

By presenting himself as the beacon of “law and order,” the Republican

candidate for president, Richard Nixon, used disturbances like the one in Chi-

cago

to get elected. Six years later, in 1974, Nixon would resign from office

to avoid impeachment by Congress concerning his role in one foul disgrace

after another. From the White House, Nixon spent six years consolidating

a Republican grasp on national political power while simultaneously and

illegally indulging his own paranoia and hunger for control. Nixon ordered

the Internal Revenue Service to pester political opponents. His appointed

henchmen illegally used funds from the Committee to Reelect the President

to pay former government agents to break into the offices of a psychiatrist

who had treated Daniel Ellsberg, the man who released the Pentagon Papers,

which

revealed previous presidents’ lies concerning the war in Vietnam. And

Nixon ordered the same team of “plumbers” to break into and bug the head-

quarters

of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate complex in

Washington, DC, in 1972, hoping the “intelligence” gathering might provide

him with nasty details that could help him get reelected. After he resigned

from office (the only president to do so), his successor, Gerald Ford, gave

Nixon a blanket pardon before congressional inquiries could sift through

the reams of evidence and determine whether to bring Nixon to trial for his

alleged crimes. No wonder Star Trek reruns became more and more popular

year after year. Captain Kirk was an ethical chief executive motivated by (an

admittedly brash) sense of responsibility, not by secrecy, lies, and paranoia

like the chief executive in the White House.

“Still crazy after all these years”:

Castr

o, Kennedy, and Khrushchev

In 1962, humans did not blow up planet Earth. In 1962, humans were, how-

ever

, afraid that they might blow up planet Earth. The fear seemed reasonable

enough. The Soviet Union, under its unpredictable, cue-ball-headed leader,

Nikita Khrushchev, had resumed atmospheric nuclear testing. Not wanting to

appear a thermonuclear weakling, President Kennedy ordered the resumption

of atmospheric nuclear testing as well. Kennedy and Khrushchev were play-

ing

Russian-American roulette with loaded hydrogen bombs and spreading

radioactive waste around the globe in the process. Khrushchev seemed like

a nutty wildcard who enjoyed bluster and threats that he might really mean.

He once yelled at one of Kennedy’s cabinet-level secretaries about America’s

hypocrisy; while U.S. atomic warheads ringed the Soviet Union from Turkey

to West Germany, Kennedy was carping about a few surface-to-air missiles

lately installed in Cuba. Khrushchev bellowed at the secretary, “Let’s not talk

about using force; we’re equally strong . . . we can swat your ass.”

3

245

IN LOVE AND WAR: 1961–1969

Although Europe appeared to be the likeliest dirt patch for a major show-

down between communists and capitalists since the close of the Korean War

in 1953, Fidel Castro, a bearded revolutionary in olive green, had changed the

equation in 1959 by overthrowing the military dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista

in Cuba. Though Castro was not originally a communist, he was brutal, and a

series of bumpy incidents with the United States pushed him into Khrushchev’s

Soviet embrace. Plus, Fidel’s younger brother, Raul, was already a communist.

The Castro brothers ran with a good friend and fellow revolutionary, Ernesto

“Che” Guevara, an Argentine doctor who diagnosed the United States with

a case of imperialism and prescribed communist revolution as the antidote.

Guevara had been in Guatemala in 1954 when CIA-funded, -trained, and -led

paramilitary forces had violently overthrown a democratically elected govern-

ment.

He witnessed the start of an American-installed, right-wing, repressive

government that led to civil war and 200,000 Guatemalan deaths by 1996,

“mostly civilian lives, with an estimated 80 percent of those deaths caused

by the U.S.-trained military.”

4

Che Guevara had real reason to see the United

States as an interfering, destructive force in Latin America.

From the outset, Fidel Castro’s relationship with the United States had

been strained. In 1958, the United States had supplied Batista’s forces

with weapons, and in return Castro’s followers had taken U.S. Marines

hostage. The crisis had been resolved peacefully, but it established a shaky

basis for friendship once Fidel Castro took control in January 1959. Also,

during the fighting against Batista’s forces, Castro had obtained weapons

from communist Czechoslovakia with the Kremlin’s okay.

5

Lines were be-

ing drawn. Then, in April 1959, while the American public was enjoying

Castro’s rumpled-bandit look during his hotdog-eating, public-relations

tour of the States, President Eisenhower refused to meet with Castro and

went golfing instead. More problematic for U.S.-Cuban relations than that

diplomatic snub was Castro’s decision to nationalize foreign-owned busi-

n

esses in Cuba, most of which were U.S. corporate property. When Castro

offered to buy the properties at the devalued rates previously claimed by

companies like United Fruit, American enchantment with Castro eroded.

Over a series of months, the United States slowed its purchases of Cuban

sugar, and Castro signed an oil deal with the Soviets. Eisenhower broke

off all relations with Castro in January 1961, just as John Kennedy was

preparing to enter the White House. In this as with so much else, Kennedy

inherited unresolved problems. Fidel Castro was originally a nationalist,

not a communist. He had wanted to empower Cubans, but the schemes and

fears of Soviets, Americans, and his own advisers had convinced him that

in order to nationalize, he would have to communize. What is more, Castro

never showed any reluctance when it came to stifling opposition at home.

AMERICAN STORIES

246

Castro’s supporters overlooked the political executions and imprisonments

he ordered. U.S. observers paid close attention.

In 1960, with Eisenhower’s approval, the CIA began training about 1,400

Cuban exiles to invade their homeland in hopes of inciting a counterrevolution

to oust Castro. The plan relied on presidential willingness to use the U.S. Air

Force to bomb Cuba in preparation for the invasion. Just before assuming the

presidency, Kennedy learned about the plan and decided to go ahead with it,

though he had serious doubts. On April 15, 1961, U.S. bombers disguised as

part of the Cuban Air Force struck lamely at Cuban airfields, destroying only

three planes. Nobody in the world was deceived by the paint job on the U.S.

bombers, and critical responses were instantaneous. So President Kennedy

temporarily grounded the bombers, which might have made a difference

for the 1,310 exile-commandos who landed the next day at the Bay of Pigs,

not far from Havana. The Bay of Pigs invasion was a short-term disaster for

Kennedy, a coup for Khrushchev, and the final inducement for Castro to go

indelibly communist.

W

ithin days of the debacle, a humbled but honest Kennedy went on national

television and assumed complete responsibility for what had happened. His

approval ratings shot up above 70 percent. The whole experience convinced

him that he should not bow to the pressure of U.S. military leaders, most of

whom had been urging him to continue the bombings on April 15 and 16.

Kennedy’s choice to be his own man paid off well in October 1962.

After Castro pronounced Cuba a socialist country, and after it was obvi-

ous

that the United States and Cuba were not going to be good neighbors,

Khrushchev decided to help his new ally by sending Castro sixty nuclear-

capable missiles, some medium-range, others able to reach as far as Maine

or the Panama Canal. The missiles, nuclear warheads, 40,000 accompany-

ing

soldiers and engineers, and launch equipment were shipped to Cuba on

innocuous-looking freighters beginning in July 1962. Given the increasing

commerce between Cuba and the Soviet Union, the ships themselves were

no cause for concern. But photo images delivered by American U-2 spy

planes told a different, more chilling tale. Misguided by the logical nonsense

of nuclear deterrence, the United States and the Soviets were following a

natural progression to the point of near disaster, partly to test the mettle and

resolve of the opponent, partly because each leader had to appear strong to

his conservative constituency, partly because that is what happens eventually

when a nation has a weapon: it gets brandished.

Ever

since 1957, American pilots had been flying U-2 spy planes over en-

e

my territory, a genuine flouting of international law. The plane itself, basically

a glorified glider, looked like a tiny needle suspended between seventy-foot

thin wings. American designers had thought the planes would remain above

247

IN LOVE AND WAR: 1961–1969

the range of Soviet or Chinese missiles, but in 1960, a U-2 was shot down

near Sverdlovsk in Russia. The pilot, Francis Gary Powers, decided not to use

his poison pin (a last-ditch suicide capsule), and he was captured, convicted

in a Soviet court, and used as proof that the Americans were not playing fair.

Eisenhower responded that, laws or no laws, the utter destructive force of

nuclear weapons necessitated spying. Even so, the U.S. military scaled back

its U-2 missions, and by summer 1962, the planes were not flying over Cuba,

though flights soon resumed.

In September 1962, rhetoric over Cuba between Kennedy and Khrushchev

heated. Both leaders made public declarations that all necessary measures

would be taken to safeguard their relative interests. They also exchanged

private letters full of bewildered language, each accusing the other of turning

up the temperature unnecessarily. Although always handsome and collected

in public, John F. Kennedy had suffered excruciating back pain for years, and

at times like these, his personal physicians concocted all sorts of remedies,

including five hot showers daily and dangerous injections of methamphet-

amines

directly into his knotted back muscles. Three billion people were sit-

ting

on his shoulders. The world’s fate literally rested on choices that could

easily be wrong. For all their posturing, neither of the superpowers’ leaders

wanted war. Still, with new evidence pouring into the White House, Kennedy

finally ordered new U-2 flights. He had to know if Khrushchev was or was not

placing nuclear warheads off the coast of Florida on the island of a dictator

against whom Eisenhower had issued assassination orders. (In fact, through

CIA intercessors, Eisenhower had dealt with senior members of the Mafia,

hoping one of their boys in Cuba could poison, stab, or strangle Commandante

Castro.) A marked man cornered on his home turf was not someone whom

Kennedy wanted to have access to the power of the gods.

By

October 16, Kennedy had irrefutable photographic evidence of missile

placements throughout Cuba. “Oh shit! shit! shit!” moaned Robert Kennedy,

who was privy to all meetings as U.S. attorney general.

6

The crisis was on.

Kennedy needed to figure out why the missiles had been placed on Cuba.

He

thought they had something to do with the delicate negotiations ongoing

between the United States, West Germany, and the Soviet Union about the fate

of West Berlin: that encircled half-city of a million people whom Kennedy

had promised to defend even unto the obliteration of all of them. In 1961, with

East German citizens streaming into West Berlin—all the essential doctors,

engineers, and other professionals—Khrushchev had ordered the Berlin Wall

to be built across the middle of the city, not to keep out the capitalists, but to

keep in the unhappy communists. The whole project was really a statement

about how poorly communism was working, but Kennedy denounced it all

the same. Believing that Khrushchev wanted some new accord over Berlin,