Roberts A.D. The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: from 1905 to 1940

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

terrible droughts in

1930—

1 and 1932—3: tens of thousands of

livestock died. The 'poor white problem', a particular concern

of Afrikaner politicians and churchmen, thus became graver than

ever. The Carnegie Commission which surveyed it in 1928-32

reported that one in five Afrikaner men were poor whites, in the

sense of being unable to obtain

a

livelihood. However, it was black

rather than white workers who were first laid off by urban

employers and, unlike whites, blacks were under pressure to

return to drought-stricken reserves. Even on the narrowest

calculation of white self-interest, the physical condition of Africans

was alarming. In 1930 the government appointed a commission

to examine how employment among unskilled whites was threat-

ened by the very low wages accepted by black migrants. The

commission reported in 1932 that the root of the problem lay in

the frequently abysmal poverty of the reserves, where an average

annual income for

a

family, in both cash and kind, was worth £14.

Rural wages quite failed to provide African workers and their

families with a diet 'consistent with reasonable maintenance of

health', and one member of the commission (the chairman of the

Wage Board) considered that the condition of African farm labour

amounted to serfdom.

24

The depression, by aggravating racial conflict, intensified the

new government's determination to suppress opposition. Already,

in June 1929, it had condoned whites in Durban who had started

a riot at the ICU office in which eight people were killed, after

Africans had protested against the municipal beer-brewing

monopoly. The minister of justice, Oswald Pirow, sought to

terrorise Africans into subservience; in November 1930 he led

armed police in Durban who attacked compounds at dawn with

tear-gas under the pretext of rounding up tax-defaulters. In the

previous May, an amendment to the Riotous Assemblies Act gave

the government sweeping powers to deal with anyone whom it

claimed was promoting ' racial hostility': these powers were soon

used against farm-workers in the western Cape, Kadalie on the

Rand, Champion in Natal, and leaders of the CPSA. The CPSA,

moreover, was divided in 1931 by new directives to detach itself

from black

'

reformists' and instead mobilise both black and white

masses for revolution; several white trade unionists were expelled.

24

Report of the Native Economic Commission, ipjo-rpji (UG 22-32), 69; C. W. de

Kiewct, A history of South Africa: social and

economic

(London, 1941), 230.

583

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SOUTHERN AFRICA

Meanwhile, there had been mounting pressure within Congress

to dissociate itself from the Communists, and in April 1930

Gumede was replaced as president by the deferential Pixley Seme.

But those in Congress who still had hopes of constitutional

advance received a new rebuff

in

1930-1,

when the voting power

of Africans in the Cape was devalued, first by the enfranchisement

of white women and then by the exemption of whites from the

' civilisation' franchise test. African rights were further eroded by

lawyers in 1934 when the Court of Appeal held that the

government did not need parliamentary authority to introduce

separate but (in theory) equal social services. It was also in 1934

that the Court of Appeal, in rejecting a challenge to the Riotous

Assemblies Amendment of

1930,

implicitly denied that judges had

any right to criticise legislation; this pronouncement was soon to

have a marked impact on judicial behaviour.

For all its severity against Africans, the Hertzog government's

handling of the economic crisis lost it a good deal of white

support. It was determined somehow to muster the two-thirds

majority needed to push through the Native Bills, but it seemed

most unlikely to achieve this on its own at the next election.

However, many Nationalists were now much readier than they

had been to contemplate alliance with Smuts's SAP. In the 1920s

the two parties were at odds over the issue of South African

autonomy. For the Nationalists, it was vital that the Union's

membership of the British Commonwealth should be the result

of choice, not constraint. At the Imperial Conference in 1926,

Hertzog asserted South Africa's right to secede, and in effect he

had his way: he influenced the drafting of Balfour's definition of

Dominion autonomy. In 1927 South Africa set up its own

department of external affairs. In 1931 the offices of governor-

general and high commissioner were separated while the Statute

of Westminster formally enacted the legislative sovereignty of

South Africa and the other Dominions. In March 1933 Hertzog

and Smuts took this accomplished fact as the basis for a wide-

ranging agreement on policy, and formed

a

coalition government;

Smuts became minister of justice and deputy prime minister. A

general election in May returned a massive majority for the

coalition and opened the way to a fusion of the two leading

parties. Early in

1934

parliament passed a Status of the Union Act

which used the Statute of Westminster to confirm South African

584

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

1924—194°

independence, and in particular its right to conduct its own

foreign policy. By September the Nationalist Party and the SAP

had merged in a new United Party. Republican-minded National-

ists feared fusion and 19 MPs followed D. F. Malan in forming

a Purified Nationalist Party; a few English-speakers, by contrast,

feared that fusion would encourage republicanism and, led by

Colonel Stallard, formed a Dominion Party.

The gold boom

During the middle and later 1930s the South African economy

expanded very considerably, chiefly as a result of the favourable

market for gold. Between the end of

1933

and 1939 the price rose

by

a

further

22

per cent. Goldmining became more important than

ever to the country's economy. Between 1932 and 1939 the annual

value of gold sales rose from £5om to £99m and usually accounted

for around three-quarters of total exports, as compared to about

a half in the previous decade. Since working costs remained

roughly stable, large profits were made. The rate of return on

goldmining capital increased and between 1933 and 1940 the

annual value of dividends was usually at least double the average

for the later 1920s.

25

These short-term gains made it possible to

secure the future of the industry in the longer term: from 1933

to 1938 it not only reinvested £nm but attracted new capital

worth £6 3 m. Due to the growth of local finance houses, notably

the Anglo American Corporation, a substantial proportion of this

new capital was contributed by South Africans, whose percentage

of mining shares rose from 14 in 1913 to about 40 in 1937.

26

This money was chiefly devoted to deepening existing mines and

developing new ones: work on the Far East Rand continued,

while from 1933 the Far West Rand was opened up. This work

did not begin to affect output significantly until the end of the

decade; indeed, output actually fell in 1933-4 and returned to the

1932 level only in 1937, since high prices rendered it economic

25

In

the decade before

the

revaluation

of

gold, the rate

of

return was around

11 per

cent, scarcely more than that

for

British equities; but

by the

mid-i93os

the

return

on

South African gold was

16

per cent while that

on

British equities fell

to 8 per

cent.

S. H. Frankel, Investment and the return to equity capital in the South African gold

mining

industry, 1SS7-19S) (Oxford, 1967),

8,

44,

124.

26

S. H.

Frankel and

H.

Herzfeld, 'An analysis

of

the growth

of

the national income

of the Union

in the

period

of

prosperity before

the

War', South African Journal

of

Economics, 1944,

12, 2,

112-15; Frankel, Capital investment,

93

n.2, IOJ.

585

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SOUTHERN AFRICA

to mill lower grades of ore. But between 1932 and 1937 the

effective mining area of the Rand was increased fourfold. Mean-

while, the diamond industry began to expand once more; the

South African cartel was reorganised in 1933 and up to 1937 the

value of sales slowly rose, though throughout the 1930s annual

output remained lower than in almost any year since 1880.

The prosperity of the goldmining industry was promptly

exploited by the government. The state was already the residual

owner of the country's gold resources: since 1908 it had gained

revenue from the industry not only by levying income tax but by

issuing mining leases which yielded a share in profits on a sliding

scale. In 1925-7 government revenue from the goldmines was

about 23 per cent of their gross profits. In 1933 the revaluation

of gold encouraged the government to introduce an excess profits

tax. Between 1932-3 and 1933-4 total government revenue rose

by almost one-third to £37.6m, of which

33

per cent came directly

from goldmining (compared with 8 per cent in 1913). In 1934-6

total direct government income from the goldmines was 42 per

cent of taxable profits and around three-quarters of the value of

dividends (compared with just over one-third ten years earlier).

27

In 1935 the goldmining industry claimed that the burden of

government levies was far heavier than that on gold-producers

in the USA, Australia or Canada, and the tax system was further

revised to increase incentives to exploit lower-grade ores and thus

extend payable reserves. Thereafter, government receipts from

goldmining gradually declined, but between 1933-4 and 1938-9

they amounted to £i

2m

— more than four times their value in the

period between 1923-4 and 1928-9.

The expansion of goldmining, and the greatly increased share

of the state in its fortunes, had far-reaching effects. Between 1932

and 1940, national income rose by about three-quarters, and in

real as well as cash terms, for prices rose little. Swollen revenues

enlarged the government's capacity to shape the economy.

Increased spending on public works boosted the construction

industry, and better roads lowered transport costs. There were

also augmented resources available to finance the apparatus of

protection for South African producers. The state-owned iron and

17

The rate of actual tax (as distinct from tax income from mining leases and credits

to the government loan account) amounted to 26, 29 and 28.5 per cent for these years.

Cf. Frankel, Capital

investment,

86, 97-8, 113, 116.

586

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

1924-194°

steel industry came into production in 1933. The value of

manufacturing output doubled between 1929 and 1939, when it

represented 18 per cent of national income; this growth was due

to protection, to the investment of mining profits and to the

establishment of South African branches by British and US firms.

The structure of agricultural subsidies continued and in 1933—7

was extended to wool-producers. Between 1910 and 1936 the

government spent £112111 on agriculture, almost wholly for the

benefit of white farmers.

The huge investment in white farming produced very mixed

results. The total output of white farmers increased, but more

slowly in the 1930s than in the 1920s. Subsidies cushioned

inefficiency as well as innovation, and they encouraged the use of

marginal land to the point of exhaustion, so that on white as well

as black farms soil erosion reached alarming proportions. The real

significance of state aid to white farming, as to manufacturing,

was political rather than economic. Hertzog's government was

much concerned to stem the drift of Afrikaners from the land.

The industrial boom increased the number of white wage-earners

by 100,000 between 1932 and 1939, while the white rural

population steadily declined. Though the 'poor white problem'

was fast disappearing, controls were still needed to prevent

unskilled white workers from being undercut by blacks. It was

thus important that the demand for jobs by unskilled whites fresh

from the land should not outstrip the capacity of employers to

pay wages appropriate to whites. In 1935 the Labour Department

spent £800,000 on subsidising job-creation for poor whites. The

Marketing Act of 1937, which further extended government

powers of farm subsidy, was specifically intended to narrow the

gap between white incomes on towns and farms.

The increased output which was encouraged by farming

subsidies required more use of African labour. White farmers who

had retained African squatters owing labour-rent increasingly

sought to replace them with full-time wage labour. Supplies were

not hard to find. The black population was steadily growing

28

, yet

the carrying capacity of the reserves was declining, especially after

the droughts of the early 1930s. Between the wars there was an

28

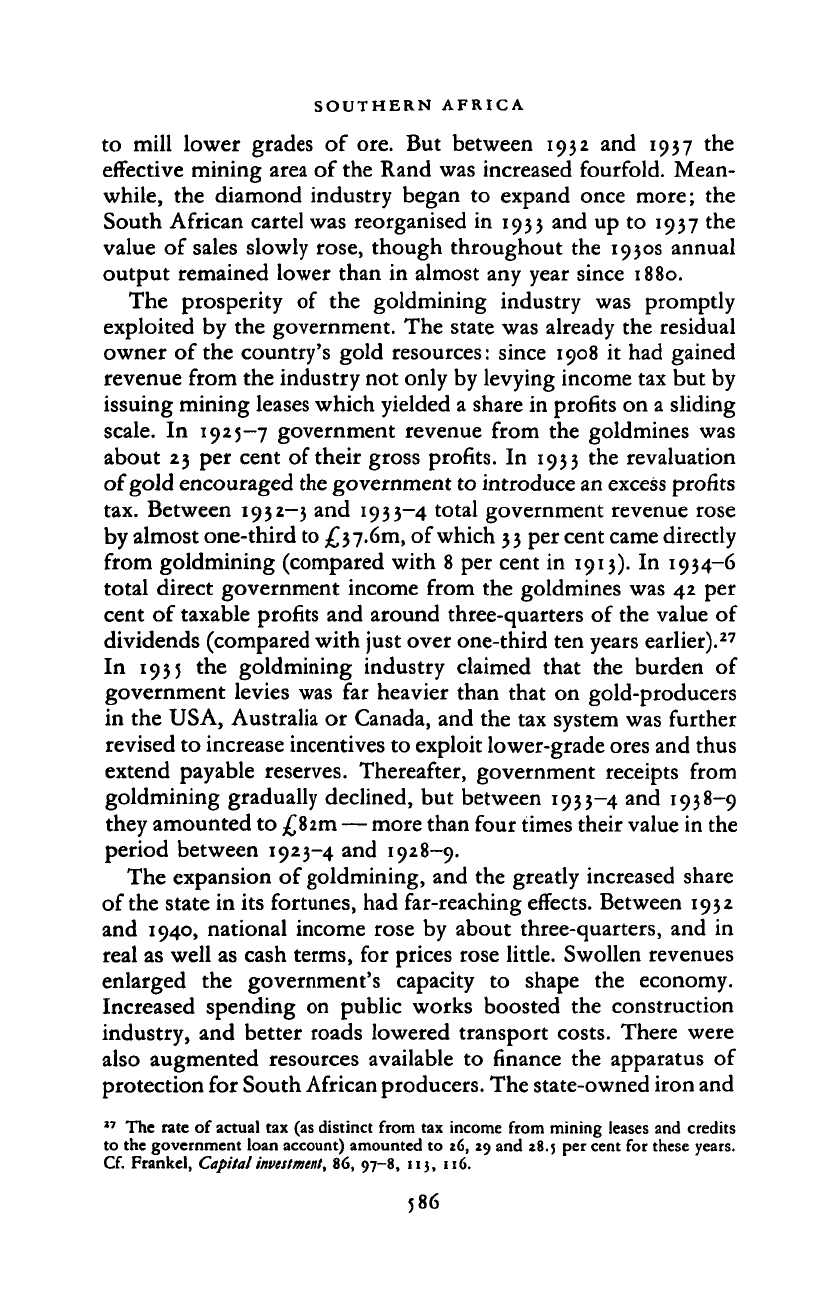

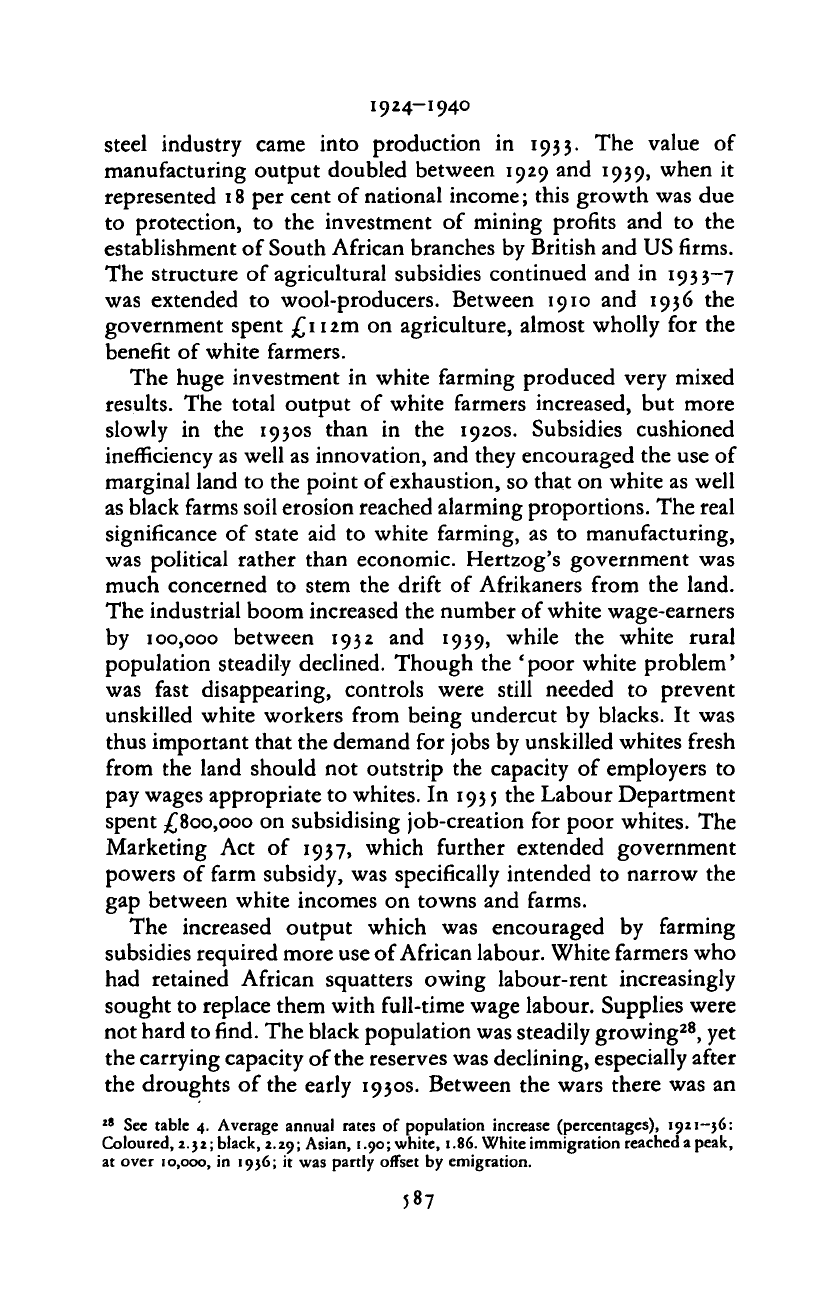

See table 4. Average annual rates of population increase (percentages), 1921-56:

Coloured, 2.52; black, 2.29; Asian, 1.90; white, 1.86. White immigration reached a peak,

at over 10,000, in 1936; it was partly offset by emigration.

587

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SOUTHERN AFRICA

Table

4.

South Africa, population

{percentages

in

parentheses).

'Natives'

Total

1

Reserves

1

White farms

2

Urban areas: total

4

''

women

5

'

6

under

14

s

*

6

Johannesburg: total''

9

women

10

women employees

10

•Whites'

Total'

Rural areas*

Urban areas'

Coloured

Total'

•Asiatic'

Total

1

Urban population

Total

5

White>

'

Native '«•»••

Coloured

5

'

6

'

Asiatic

>5

>

6

1911

4,019,006

508,142 (126)

101,971

4357

1,276,242

617,9)6

6)8,286

5*5.943

152,20)

1,477,868

658,286(44)

508,142

()4))

1921

4,697,81)

j 87,000(125)

'47.*93

87,000

118,652

12,160

5633

1,519,488

671,980

847,508

545.548

'65.73'

'.7)5.795

847.

J 08 (49)

587,000 ()))

249,968 (i4"4)

JI,2O9()O)

19)6

6,596,689

2,42O,)49

2,O5),44O

1,141,642(17))

356.874

226,944

2)1,889

60,992

24,781

2,OO),857

696,471

1,307,586

769,661

219,691

3.OO9.5

3'

1.307.386

(434)

1,141.64*

(380)

414.907 (>3'8)

I45.J96

(4'8)

1

Official yearbook

of

the Union

of South Africa,

no. 22

(1941),

984.

1

Ibid.,

398.

1

Ibid.,

99).

4

Union

yearbook:

statistics for

the period

1910-2) (1927),

86).

5

Ibid.,

864.

6

Report on

1936

Census,

vol.

IX

(UG 50,

19)8).

7

Report of the Native Lavs

Commission

(UG 28,

1948),

6.

8

J. P. R.

Maud, City

Government

(19)8),

584.

•

Report on

1946

Census,

vol. X (UG 51,

1949),

78ff.

10

Gaitskell,

as

cited

on

p. 590,

n. 52.

overall,

if

still very gradual, decline

in

agricultural productivity

in

the

reserves.

29

And

despite

the

great increase

in

government

revenue after 1934 there was no reduction

of

African taxation.

By

1937 there were 400,000 Africans working

on

white farms

(as

against 360,000

in

1930), and once there they were frequently tied

2

» Steep decline dates only from

the

1950s:

cf. C.

Simkins, 'Agricultural production

in

the

African reserves',

Journal

of

Southern

African Studies, 1981,

7, 2,

256-83.

588

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

down not only by pass-laws but by cash debts and much-prized

grazing rights. The latter helped workers to support families:

altogether, there were over two million Africans living on white

farms in 1936. But the combined effect of immiseration in the

reserves and artificial barriers to mobility was to depress real farm

wages even below their value in 1910.

Other fields of employment expanded fast. Between 1929 and

1939 the black workforce in manufacturing nearly doubled, while

that on the mines rose by one-third to 424,000, the first major

increase since 1907—10. During the worst of the depression, from

1929 to 1933, the Transvaal mines reduced their reliance on

contract labour from Mozambique

30

in favour of men from

within the Union, of whom only 40 per cent were contracted by

labour recruiters. In the same period, the proportion of mine-

workers from the Cape in the Transvaal rose from 30 to 43 per

cent, even though by 1935 one-third of job-seekers from the

Transkei were rejected by the mines on medical grounds. Mean-

while, the recent discovery of a sulphonamide drug provided a

cure for the pneumonia to which mineworkers from the tropics

were specially prone. In 1934, under pressure from the mine

companies, the government allowed a gradual resumption of

recruitment north of latitude 22°S, and by 1939 the Transvaal

mines employed some 20,000 men from central Africa, mostly

from Nyasaland. On the goldmines, increasing mechanisation

underground widened the scope for white workers: by 1939 there

were 43,000, almost twice as many as in the later 1920s. However,

there was no marked change in real wages for either black or white

mineworkers, which in 1941 were much the same as they had been

in

1911.

31

This was broadly true of workers in other industries

and in government or municipal employment. Annual wages for

black workers in manufacturing averaged £41 to £46 in 1924-37;

mineworkers earned two-thirds as much.

By and large, the boom in goldmining had the effect of

intensifying existing trends towards white proletarianisation and

black dependence on wage labour. Between 1921 and 1936 the

number of whites in urban areas increased by a

half,

yet that of

blacks in urban areas doubled. Moreover, there were clear signs

that Africans were tending increasingly to make their homes in

J0

A new labour convention had been made with Portugal in 1928; cf. p. 516.

Jl

F. Wilson, Labour in the South African gold

mines,

1911-1969 (Cambridge, 1972), 46-

589

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SOUTHERN AFRICA

towns. Whereas in

1921

there were three black men for every black

woman in towns, in 1936 the ratio was only

2.2:1,

and a larger

proportion of urban Africans were children. African settlement

had gone much further in some towns than in others: in Port

Elizabeth, the sexes had long been evenly balanced. The patterns

of urbanisation were clearest on the Witwatersrand. By 19 j

7

the

total population of the area was over a million, and over half were

Africans. Most Africans in employment were housed by their

employers, usually as single men (as on the mines); they were

certainly transient. But the increase in African urban employment

meant more opportunities for self-employed Africans such as

retail traders, craftsmen and herbalists. Besides, there were said

to be over 90,000 Africans 'living by their wits', without

any obvious source of income. And the 60,000 who lived in

Johannesburg's municipal locations consisted mostly of families;

they were regarded by officials as permanent residents. Between

1921 and 1936 the black female population of Johannesburg

increased fivefold, and less than half were in white employment

(mostly as domestic servants). Over 500 Africans had bought land

in areas set aside by the municipality for 'non-white' owner-

occupiers, while others owned plots outside the city boundary.

32

Segregation

The growth of African urban settlement between the wars

sharpened racial antagonism. The more stabilised Africans threat-

ened white jobs; the

L-umpenproletariat

threatened social order.

There was increasing pressure to keep Africans out of towns,

except as temporary wage-earners. In 1930 there were 40,000

convictions under the pass-laws, and the government empowered

municipal authorities to exclude women who could not prove they

had accommodation. But there was also wider-ranging debate on

the place of Africans in South African society. Hertzog's Native

Bills became a focus for the discussion of segregation at all levels.

The 1926 bills had been referred to a parliamentary committee

which included the member for Zululand, G. Heaton Nicholls,

32

Ray E. Phillips, The

Bantu

in the city (Lovedale, 1958), xxiv, xxvi—xxvii; Deborah

Gaitskell, "Christian compounds for girls": Church hostels for African women in

Johannesburg, 1907-1970'',

journal

of

Southern

African

Studies,

1979, 6, 1, 48. Neither

the 1913 Land Act nor the 1936 Native Trust and Land Act applied to urban areas.

590

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

i924—1940

a leading sugar-planter. In 1931 Nicholls (echoing recent state-

ments by Smuts) argued that the only way to prevent African

proletarianisation and consequent class war was to strengthen the

economic resources of the reserves and foster African 'race pride'

by restoring the power of African chieftainship. In these objectives

he had the support not only of the Zulu royal family but also of

John Dube, the ANC leader. Dube, like other educated Zulus,

was related to a chiefly family and in the 1920s made common

cause with the richer African farmers who themselves employed

wage labour and shared white fears of the ICU. Such Africans also

had an interest in playing down class-conflict, and to this end

sought both to relieve mounting pressure on land and to

strengthen attachment to traditional rulers. In 1931 Dube told

Nicholls that Africans wanted land, not votes, and he toured the

Union to gain African support for Nicholls's plan to couple the

disfranchisement of black voters in the Cape with a large

extension of the reserves and special funds for their development.

Hopes that segregation could be given some such positive

content received little encouragement from the bills presented to

parliament in 1935. The Native Trust and Land Bill finally

adopted the recommendations of the Beaumont Commission in

1916 to increase the extent of'scheduled areas' in African owner-

ship by about 75 per cent.

33

But this reform was hedged about

with qualifications. Africans might continue to buy land within

the enlarged scheduled areas, but out of their own pockets; all

the remaining additional land would eventually be bought for

communal ownership through

a

government fund, and occupation

would be conditional on satisfying official standards of land use.

Thus chiefs, who distributed communal land,-were favoured at

the expense of prospective African freeholders. Besides, much of

the additional land was already occupied by Africans living on

white property, so that the bill's effect on land scarcity was slight.

Furthermore, Africans in the Cape were finally prohibited from

buying land from whites outside scheduled areas. At the same

time,

the bill obstructed African farming on white land; it

outlawed cash tenancies and extended to 180 days the period of

service which could be exacted from labour tenants. The political

11

This figure takes account of some 2.5 million acres bought by Africans since 1913

with the governor-general's permission: cf. T. R. H. Davenport,

South

Africa: a

modern

history

(London, 1977), 336; the real gain was thus only 63 per cent.

59

1

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SOUTHERN AFRICA

segregation of Africans was adumbrated by the Natives Repre-

sentation Bill. This proposed to disfranchise African voters in the

Cape and outlined a separate structure of African representation.

For each province, one white senator would be chosen

by an

electoral college consisting of chiefs, headmen and other African

local authority officials; these colleges would also elect twelve

members of an advisory Natives Representative Council, which

would also include four nominated members and six officials.

The bills provoked concerted African criticism. In December

193 5

an All-African Convention at Bloemfontein brought together

delegates from numerous organisations. Congress members of all

shades of opinion were prominent; already Dube was disenchanted

with segregation and declared: 'The Government

is

trying

to

replace what

it

has already destroyed — our tribal system. '

34

Communists also took part; since the advent of Hitler, their party

line had swung round again to favour a broad popular front.

In

February 1936 Hertzog received

a

deputation from the A AC

headed by D. D.

T.

Jabavu, leader of the Cape Native Voters'

Convention. More persuasive, however, were

a

group

of

Cape

MPs whose support was needed to pass the bills. They induced

Hertzog to allow Africans removed from the Cape common roll

to elect instead three whites

to the

lower house. With this

alteration,

the

Native Bills obtained

the

necessary two-thirds

majority in April and became law.

Within parliament, the most powerful attack on the Natives

Representation Bill

in its

final form had come,

not

from

the

Nationalist opposition,

but

from

a

Cabinet minister,

J. H.

Hofmeyr (then

in

charge

of

education, the interior and public

health). More consistently than Smuts, Hofmeyr believed that

relations between black and white

in

South Africa should

be

guided

by

the principles

of

trusteeship proclaimed

by

colonial

regimes further north. Trusteeship was, of course,

a

cant word

freely used

for

political advantage;

it

was Hofmeyr's merit

to

point this out:

I have always regarded trusteeship as implying that at some stage or another,

the trustee is prepared to hand over the trust to his ward.

I

have yet to learn

that the European trustee in South Africa contemplates any such possibility.

And that being so,

I

find it very difficult

to

reconcile the use of the word in

34

S.

Marks, 'The ambiguities of dependence: John L. Dube

of

Natal',

Journal of

Southern African Studies, 1975,

1, 2,

179.

59

2

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008