Roberts A.D. The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: from 1905 to 1940

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BRITISH CENTRAL AFRICA

I BECH UA N

A

L AN

D

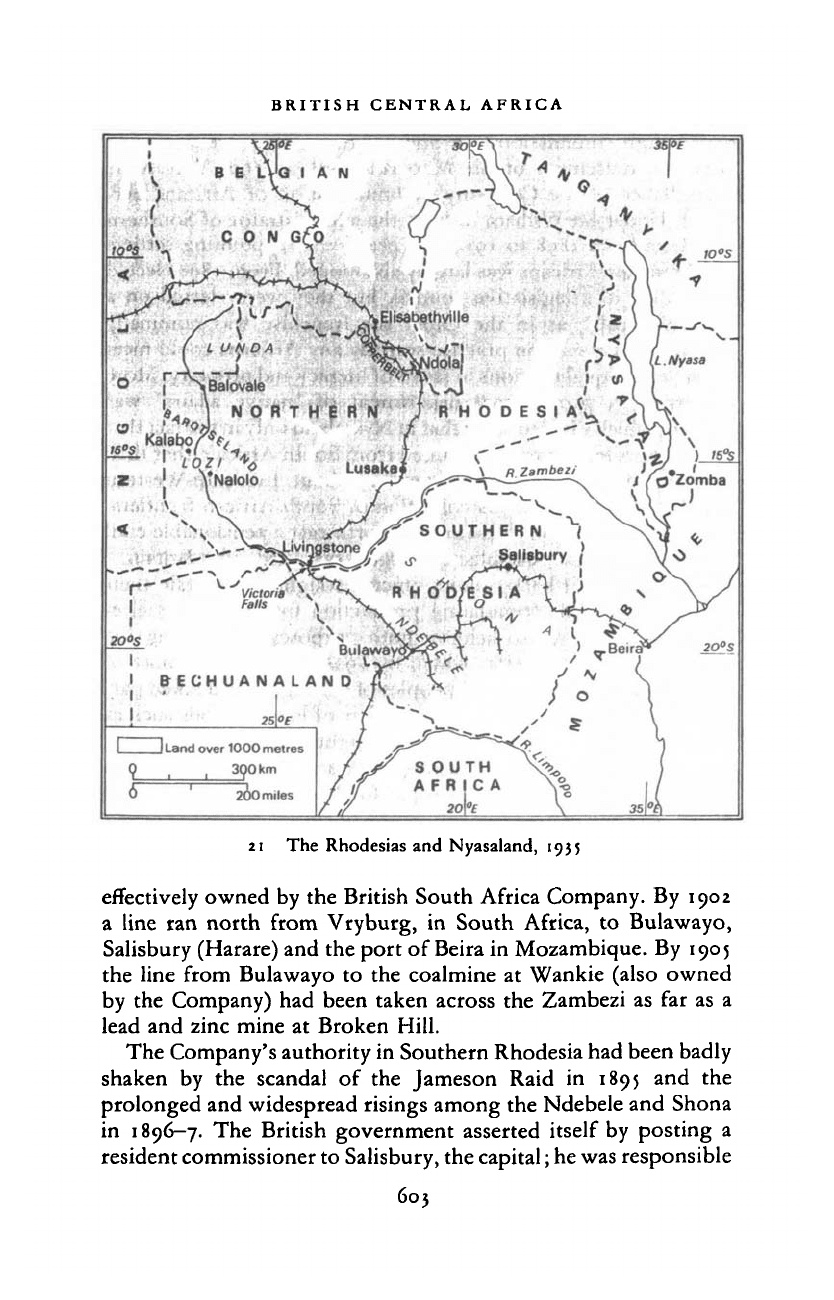

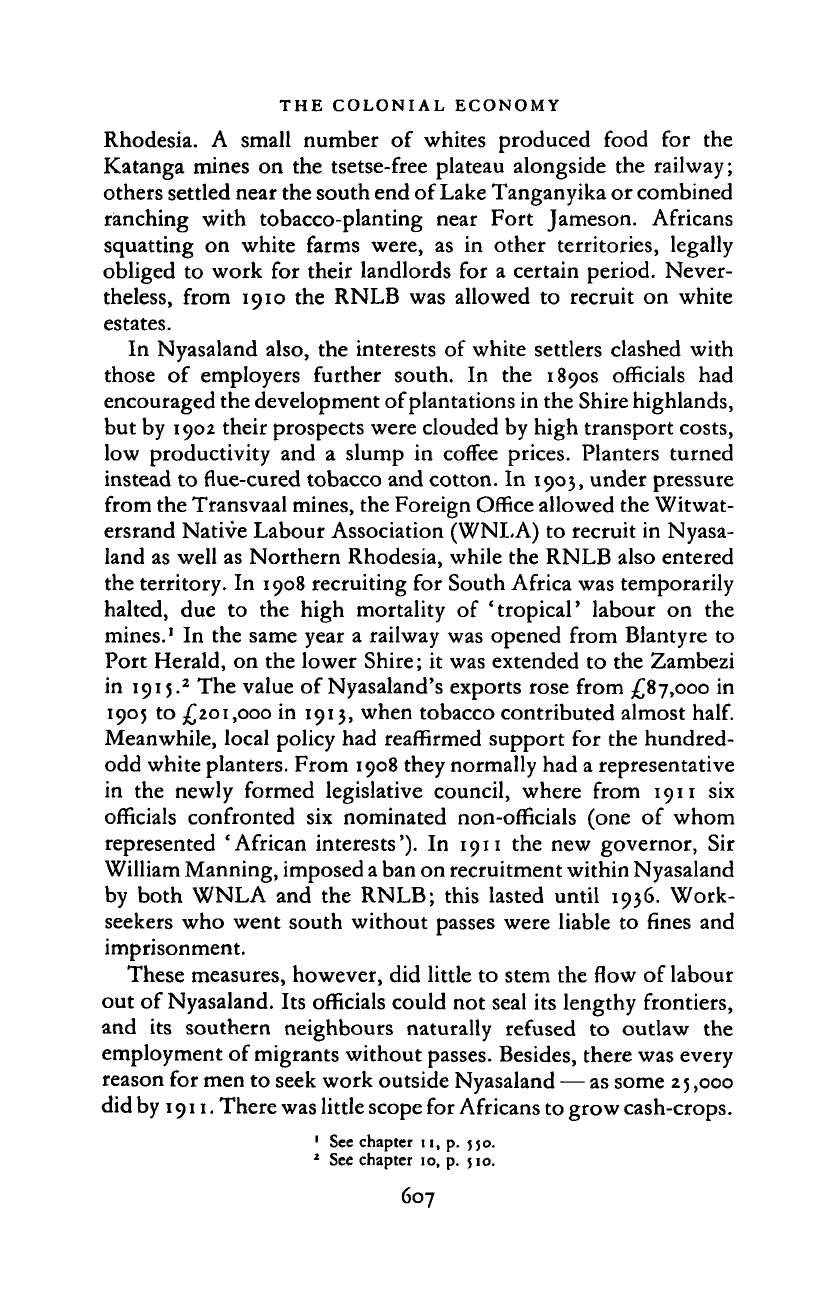

21 The Rhodesias and Nyasaland, 1935

effectively owned by the British South Africa Company. By 1902

a line ran north from Vryburg,

in

South Africa,

to

Bulawayo,

Salisbury (Harare) and the port of Beira in Mozambique. By 1905

the line from Bulawayo to the coalmine at Wankie (also owned

by the Company) had been taken across the Zambezi as far as

a

lead and zinc mine at Broken Hill.

The Company's authority in Southern Rhodesia had been badly

shaken

by

the scandal

of

the Jameson Raid

in

1895 and

the

prolonged and widespread risings among the Ndebele and Shona

in 1896-7. The British government asserted itself by posting

a

resident commissioner to Salisbury, the capital; he was responsible

603

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH CENTRAL AFRICA

to the high commissioner in South Africa. Vigilance slackened

after the retirement of Sir Marshall Clark in 1905, but some

surveillance of the Company's administration of Africans per-

sisted. Under Sir William Milton, the administrator of Southern

Rhodesia from 1898 to 1914, the practice of appointing settlers

to administer Africans was largely abandoned. From 1898 elected

settlers sat in a legislative council, but they were elected on a

'common roll', as in the Cape: the franchise was nominally

colour-blind even if in practice scarcely any Africans could meet

the stringent qualifications in terms of literacy and property. More

important, a professional department of 'native affairs' was

created, which differed from that in Nyasaland only in the fact that

its members tended to be recruited from South Africa rather than

Britain and were less frequently moved about. In North-Western

Rhodesia a heterogeneous collection of South African frontiers-

men continued to serve, but in the north-east a pensionable civil

service was quickly established, largely recruited from Britain.

Whatever their background, officials sought to maintain their

rule cheaply while stimulating production for export. As else-

where, they sought to achieve both purposes by exacting the

payment of taxes in cash, which by 1905 was usual in most of

central Africa. Hitherto, the peoples of the region had taken part

in overseas trade principally as suppliers of luxury goods such as

gold dust and ivory. Now they were sought as labour for the gold,

copper and coal mines of central and southern Africa and as

producers of food and cash-crops: food for the workers in the

mines, tropical staples for the international market. One aspect

of the change was the drastic reshaping of regional economies:

the severing of nineteenth-century links with the East African

coast and the growing integration of the northern territories into

the mining economy of the south. Another was the increasing

influence of international, non-African events, exemplified most

dramatically by the crushing impact of the First World War and

later of the depression in the 1930s. Central Africa in the twentieth

century was thus a periphery of the economies of South Africa

and the West, its inhabitants subject to economic and political

fluctuations over which they had little control. But at no time did

they lose the capacity to influence the character of the economic

and social environment in which they were forced to operate.

604

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE COLONIAL ECONOMY

THE MAKING OF THE COLONIAL ECONOMY, 1905-1914

At the turn of the century, the goldmining industry of Southern

Rhodesia was in crisis. Early hopes of

a

'second Rand' had been

disappointed and

in

1903

the

London market

for

Rhodesian

mining shares collapsed. The British South Africa Company

belatedly began to encourage small workers, since few economies

of scale could be achieved where gold deposits were small and

reefs unpredictable. Labour costs were cut

to

the bone; where

possible, Africans were employed as skilled labour, yet their wages

were reduced

by

minimising competition among employers.

From 1903 the Rhodesian Native Labour Bureau (RNLB) recru-

ited workers on long contracts, especially north of the Zambezi,

and the number

of

African mineworkers

in

Southern Rhodesia

rose from 17,300 in 1906 to 34,5 00 in

1912.

By 1909 over 5 00 small

mines were being worked; capital began

to

flow back into the

industry and the value of gold output rose from £1. im in 1904-5

to £3.6m

in

1913-14; usually

it

accounted

for

90 per cent

of

exports.

The reconstruction of the mining industry was accompanied by

an attempt to develop white farming. Before 1905 or so, whites

and their black workers had largely relied for food on African

produce. By 1899, 15.8 million acres had passed into white hands,

but most had been left vacant, pending a rise in land values. The

company now sought

to

hasten this process and increase traffic

on its railways by promoting white farming. From 1908 settlers

were sought in Britain and South Africa; land prices were reduced

far below those in South Africa; training schemes for new farmers

were introduced and in 1912 a Land Bank was set up to provide

loans

for

white farmers.

Few

settlers

in

fact possessed

the

combination of capital and skills which the company sought

to

attract. More than nine-tenths came from South Africa,

a

higher

proportion than had originally been intended. Yet while many

white farmers failed, others prospered. Their total numbers rose

from 545 in 1904 to 1,324 in

1911;

they were cultivating less than

184,000 acres

in

1914

but had

made significant advances.

Throughout much of Mashonaland they grew maize, initially

to

feed African mineworkers but from 1909 for export to Britain as

well. Cattle-ranching expanded, on the basis of herds seized in the

1890s both from

the

Ndebele and from Mpezeni's Ngoni

in

North-Eastern Rhodesia. Whites also began

to

grow tobacco,

605

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH CENTRAL AFRICA

which offered a quick return on capital and could be successfully

cultivated

on

sandy soils rather than on the rich .red loams

to

which settlers had previously been attracted. For

a

brief period

from 1909, tobacco-production expanded rapidly but by 1913 the

South African market had been saturated, prices fell and the infant

industry virtually collapsed.

By this time competition between European

and

African

farmers was intensifying, with Europeans seeking to convert the

local population into cheap reliable labour, while African farmers

sought to produce more foodstuffs to meet the mounting demand.

Only

in

the 1930s was there

a

significant overall decline

in

the

production of grain per head of African population. But in some

areas,

such as Victoria District, even before 1914 the weight of

taxation and rents, combined with poor communications, had

turned previously prosperous peasants into poverty-stricken

migrant workers. White settlers criticised the company for having

set aside some 20 million acres

as

reserves

for

Africans, even

though these were on the fringes of white-owned land and mostly

remote from the main markets.

In

1915

a

commission under Sir

Robert Coryndon recommended that the reserves be reduced by

one million acres while also being deprived of much fertile land

in exchange

for

poorer land: these measures were eventually

approved by Britain in 1920.

For the British South Africa Company, its territories north of

the Zambezi were essentially appendages to Southern Rhodesia.

Gold deposits were insignificant

and the

surface deposits

of

copper oxide, once worked by Africans, were too poor to attract

large-scale investment, though whites began some small-scale

mining at Kansanshi and in the Hook of the Kafue. The Company

mainly valued Northern Rhodesia as

a

source of labour for the

mines of Southern Rhodesia. Hut-taxes, payable in cash, served

to prise out workers; from time

to

time African police burned

the homes and crops

of

defaulters; and agents

of

the RNLB

collected men from district headquarters. The copper-mines

in

Katanga also sought to recruit men in Northern Rhodesia, which

suited the company inasmuch as its railway, which was linked to

Elisabethville (Lubumbashi)

in

1910, carried coal north from

Wankie and exported Katanga's copper to Beira. But the labour

requirements

of

Southern Rhodesia remained paramount over

both those of Katanga and those of white farmers

in

Northern

606

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE COLONIAL ECONOMY

Rhodesia.

A

small number

of

whites produced food

for the

Katanga mines

on

the tsetse-free plateau alongside the railway;

others settled near the south end of Lake Tanganyika or combined

ranching with tobacco-planting near Fort Jameson. Africans

squatting

on

white farms were,

as in

other territories, legally

obliged

to

work for their landlords for

a

certain period. Never-

theless, from 1910 the RNLB was allowed

to

recruit

on

white

estates.

In Nyasaland also, the interests of white settlers clashed with

those

of

employers further south.

In the

1890s officials

had

encouraged the development of plantations in the Shire highlands,

but by 1902 their prospects were clouded by high transport costs,

low productivity and

a

slump

in

coffee prices. Planters turned

instead to flue-cured tobacco and cotton. In 1903, under pressure

from the Transvaal mines, the Foreign Office allowed the Witwat-

ersrand Native Labour Association (WNLA) to recruit in Nyasa-

land as well as Northern Rhodesia, while the RNLB also entered

the territory. In 1908 recruiting for South Africa was temporarily

halted, due

to the

high mortality

of

'tropical' labour

on the

mines.

1

In the same year

a

railway was opened from Blantyre

to

Port Herald, on the lower Shire;

it

was extended to the Zambezi

in 1915.

2

The value of Nyasaland's exports rose from £87,000 in

1905 to £201,000 in 1913, when tobacco contributed almost

half.

Meanwhile, local policy had reaffirmed support for the hundred-

odd white planters. From 1908 they normally had a representative

in

the

newly formed legislative council, where from 1911

six

officials confronted six nominated non-officials (one

of

whom

represented 'African interests').

In

1911 the new governor,

Sir

William Manning, imposed

a

ban on recruitment within Nyasaland

by both WNLA and the RNLB; this lasted until 1936. Work-

seekers who went south without passes were liable

to

fines

and

imprisonment.

These measures, however, did little to stem the flow of labour

out of Nyasaland. Its officials could not seal its lengthy frontiers,

and

its

southern neighbours naturally refused

to

outlaw

the

employment of migrants without passes. Besides, there was every

reason for men to seek work outside Nyasaland — as some

2

5,000

did by

1911.

There

was

little scope for Africans to grow cash-crops.

1

Sec chapter

n,

p. 550.

2

See chapter 10, p. 510.

607

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH CENTRAL AFRICA

l,fcXi..l

Land over 1000metres

O , 300 km

6 ' 5o\)miles

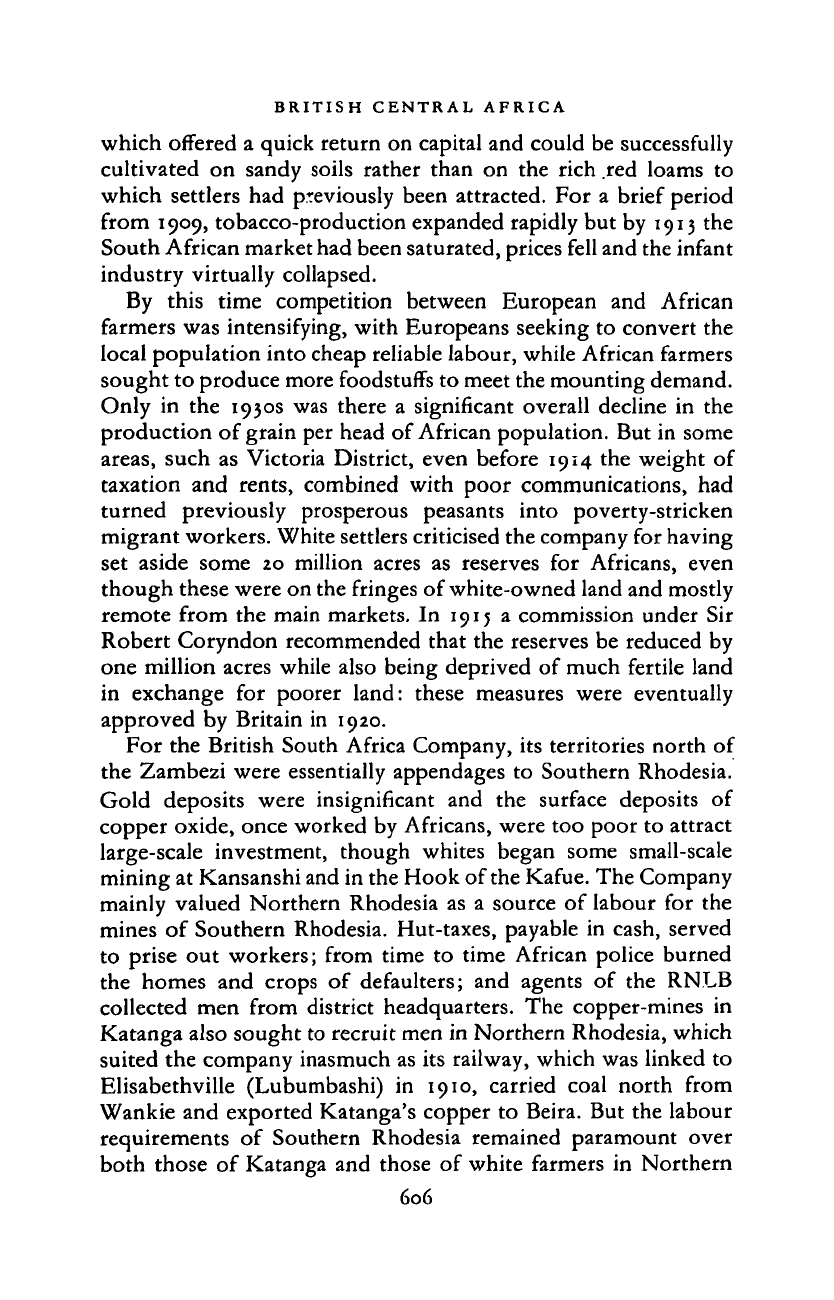

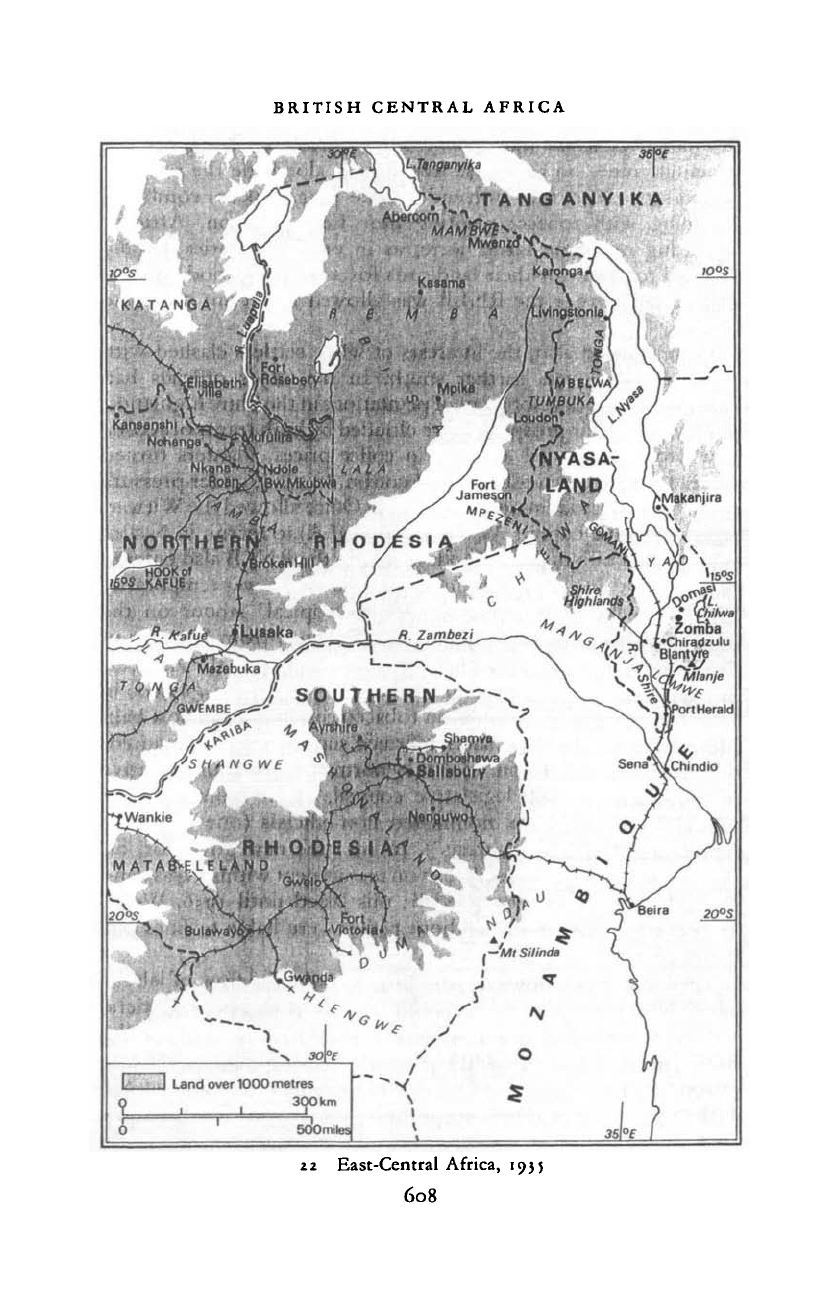

22 East-Central Africa, 1935

608

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE COLONIAL ECONOMY

In the Shire highlands, Yao and Manganja supplied food to white

estates.

In 1911 the

British Cotton Growing Association

encouraged African production

by

opening ginneries

at

Port

Herald

and

Karonga.

The

results were promising,

but the

government obstructed African cotton-growing in Blantyre and

Zomba districts, the main areas of white production. This helped

depress wage-levels on white plantations, which were lower than

anywhere else in southern Africa. Africans living on the extensive

tracts alienated

to

whites were tenants-at-will, forced either

to

grow cash-crops at a price fixed by the local planter, or to provide

labour

in

exchange

for

rent and taxes

— a

practice known

as

thangata.

Planters could exact such servitude partly because the law

approved

it but

also because

it

offered

at

least some hope

of

subsistence to the wretched Lomwe villagers (known pejoratively

as Nguru) who fled

to the

Shire highlands from still worse

conditions

in

Portuguese territory.

3

Once

in

Nyasaland, such

Lomwe were trapped; they were not simply temporary labour

migrants but permanent emigrants who had brought their families,

and these were liable

to

eviction

if

their menfolk sought work

elsewhere. Thus the Lomwe were

at

once the most exploited

group within

the

protectorate and also,

in a

sense,

the

most

crucial: their very cheap labour made possible Nyasaland's own

modest exports of commodities and also stimulated its exports of

labour.

The new economic order bore hardly on many

of

those who

had organised local exploitation

in

the nineteenth century. The

slave-trade was suppressed: by 1912 Company officials had halted

the export

of

men from north-western Northern Rhodesia

to

Angola and the cocoa plantations of Sao Tome. The ivory trade

was crippled

by

customs duties

and

restrictions

on

African

ownership of guns. The Yao, around the southern end

of

Lake

Malawi, had lately been prosperous caravan traders; instead, they

tried cotton-growing but transport cost too much. They thus

turned to wage labour; first as unskilled porters, then as policemen

and

as

soldiers with the King's African Rifles,

for

whom they

usually provided half

of

Nyasaland's

two

battalions.

Yet the

system they upheld impoverished their home:

by

1938

the

once-thriving country of the Yao chief Makanjira could no longer

feed itself and was designated a 'distressed area'. Colonial rule also

3

See chapter 10, p. 505.

609

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH CENTRAL AFRICA

undermined regimes which had relied on raiding, tribute levies

and the accumulation of cattle. Whites took much land from the

Ndebele and the Ngoni kingdom

of

Mpezeni, and confiscated

cattle from them and from Gomani's Ngoni. The sale

of

the

remaining Ngoni herds was checked by the spread of tsetse from

about 1905,

the

result

of

official protection

of

game and

the

concentration of villages to facilitate colonial control. Both Ngoni

and Ndebele were largely drawn into migrant labour, and their

agriculture suffered from lack

of

manpower. Eastern Northern

Rhodesia and parts of central Nyasaland sank into an ecological

crisis,

as game increased (following a ban on African use of

guns),

the bush expanded and sleeping-sickness spread.

For the rulers of

the

Lozi kingdom, on the upper Zambezi, the

colonial economy was at first less damaging. They lost no land

to white settlers, and special treaties concluded with the Company

in 1898 and 1900 had preserved important privileges, even if these

were later reduced. From 1906 Lozi chiefs received

a

fixed

percentage of taxes; they also benefited from their ownership of

mound sites in the fertile Zambezi flood plain and their control

of cattle and tribute. The end of domestic slavery in 1906 deprived

councillors of a valuable source of cheap labour, but

it

did not

much affect the king, who retained some rights to tribute labour

in his fields. The cattle

of

Lozi herds had largely escaped the

rinderpest epidemic which had swept through eastern and south-

ern Africa

in

the 1890s; they were thus

in

much demand from

mines and white farms. King Lewanika, the most substantial

cattle-owner, also grew maize and vegetables for sale to whites

and had canals dug to increase the area of fertile land.

In

1915,

however, the Lozi cattle-trade was suddenly checked, following

an outbreak

of

pleuro-pneumonia which officials sought

to

control by banning stock movements. With the loss of an income

from cattle, Lozi rulers became increasingly dependent on govern-

ment pensions. Labour migration sharply increased, which

impeded labour-intensive tasks such as canal-digging.

The peoples of northern Nyasaland were also obliged to seek

cash through wage-earning, but were better placed than most to

do so. The schools of

the

Scottish Livingstonia Mission imparted

skills of language and literacy which enabled northern Nyasas to

obtain positions of comparative privilege in the labour centres of

Southern Rhodesia, South Africa and Katanga, as well as gaining

610

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE COLONIAL ECONOMY

a high proportion of the salaried posts open to Africans in

Nyasaland.

4

Mission-sponsored schemes for agricultural advance

were largely unsuccessful in an area where, by the 1930s, half the

able-bodied men were absent from their homeland. But by

remitting money home in order to buy education for their

families, northern Nyasas were able to maintain a certain freedom

of choice in relation to the labour market which other Central

Africans were denied.

The southward flow of labour migrants across the Zambezi was

partly due to the early success of Africans in Southern Rhodesia

in producing for the market. It has been estimated that in 1903

their sales of grain and stock were worth £350,000, nearly three

times their earnings from wages.

5

Most were Shona: some, like

the Duma of the south-east, added the production of maize for

the colonial market to a continuing internal trade in grain to their

neighbours, the Hlengwe. Others, like the Shangwe of the Inyoka

country, expanded the production of indigenous tobacco for sale

to white traders. By 1914 this enabled the Shangwe not only to

pay their hut-tax but to buy clothing, blankets, beads and enamel

ware. In a few places, especially near Salisbury and Bulawayo,

Sotho and Zulu evangelists bought land on which they employed

wage labourers to grow vegetables for the urban market. Sales

of ploughs to Africans expanded rapidly. All the same, increases

in production resulted mainly from rising inputs of labour, so that

the consequences for indigenous economies were not entirely

beneficial: hunting and village crafts suffered, and habits of

ecological control were neglected in the pursuit of cash incomes.

For all the transforming effects of colonial rule, many Africans

were touched only marginally by them before 1914. So few

administrators were posted to the northern province of Nyasaland

and the huge areas beyond the line of rail in Northern Rhodesia

that the payment of tax was often avoided. As late as 1921, many

people in the Balovale, Kalabo and Nalolo districts near the

Angola border were said to have never paid tax. Some local

industries were undoubtedly injured by competition from impor-

ted mass-produced goods sold by store-keepers — Indians in

4

Sec below, p. 617.

5

G. Arrighi,' Labour supplies in historical

perspective:

a

study of the proletarianisation

of the African peasantry in Rhodesia', in G. Arrighi and J. S. Saul,

Essays on

the political

economy

of Africa (New York and London, 1973), 185, 225.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH CENTRAL AFRICA

Nyasaland, Jews and Greeks

in

Northern Rhodesia; but others

survived

and

even flourished. Fish from

the

Luapula were

supplied to neighbouring cultivators, as of old, as well as to the

Katanga

mines.

High transport costs could insulate local industries

from overseas competition. Salt-production persisted near Mpika,

in Northern Rhodesia, and

on

the shores

of

Lake Chilwa

in

Nyasaland.

In

parts of central and western Northern Rhodesia,

iron hoes continued to be made and in the 1930s were regarded

as better than imported German hoes.

CLASS, RACE

AND

POLITICS, 1905 —1914

The birth of the new economy was associated with the emergence

of new forms of racial and social division. For the infant settler

communities, racial dominance was as much a matter of economic

necessity

as

of cultural preference. White farmers and mine-owners

were

at

one

in

requiring regular supplies

of

cheap, unskilled

labour, and

to

this end they agitated

for

measures that would

reduce

the

capacity

of

Africans

to

function

as

independent

agricultural producers and that would force them into taking

employment with whites. Though

a

formal structure

of

racial

discrimination in economic affairs was not completed in Southern

Rhodesia until the 1930s, many elements existed in practice from

the early years of the century. Europeans in all three territories

were provided with privileged access to land and were supported

by discriminatory taxation systems aimed at forcing Africans into

European employment. Public funds were largely devoted

to

European activities. An informal colour bar existed throughout

industry, devised not only

to

protect European workers from

African competition,

but

also

to

limit

the

social costs that

employers were required to bear.

Maintenance

of

white supremacy thus became the central,

if

largely undiscussed, imperative of settler politics, though conflicts

of interest occurred where English-speakers clashed with Afrik-

aners and workers with their employers or where small farmers

and large mine-owners competed for African labour. The' farmers'

revolt'

of

1911—12

in

Southern Rhodesia is

a

notable example.

When a labour-tax was levied on employers to meet the adminis-

trative costs of the RNLB, more than 800 white farmers refused

to

pay on the

grounds that

the

bureau benefited only

the

612

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008