Schmitt C.B. (ed.) The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The

concept

of

psychology

457

Agostino

Nifo

identified the chapters on intellect in De

anima

as

part

of

metaphysics and referred to psychology in general as a 'middle science'

(scientia

media)

between that discipline and physics.

10

Finally, De

anima

expounded the principles

of

intellection and thus contributed to the general

theory

of knowledge and supplemented logical rules of

argument:

only

when logic was understood not as a science in itself but as instrument

of

the

sciences was the psychological theory of knowledge dissociated from it.

11

Non-philosophical disciplines, too, relied on the study of psychology:

theology, as is obvious in the debate on immortality;

12

rhetoric,

which

drew

its force from the appeal to senses and emotions; and medicine, which

also considered the human body. The ties to the last were particularly

strong:

philosophers writing on the soul incorporated many ideas from

Galen, Avicenna and more

contemporary

medical theorists,

while

much of

the

basic physiology contained in De

anima

and the

Parva

naturalia

reappeared

in courses on medicine and served in the understanding and

treatment

of mental and physical disease. For this reason the philosophy

curriculum

at Bologna, intended as propaedeutic to the study of medicine,

put special emphasis on De

anima.

13

In general, therefore, psychology was

seen both as the apex

of

natural

philosophy and as a transition to the higher

study of medicine.

The

many contributions of psychology to other disciplines vindicated

the

centrality of De

anima

in the university curriculum. At the same time,

they opened the discussion

of

the

soul to other intellectual influences. These

included humanism, with its emphasis on anthropological and moral

questions; Neoplatonism, with its attempt to develop

a

new cosmology and

epistemology; and the religious movements of

Reformation

and Counter-

Reformation.

As a result psychology, like ethics, never remained the

monopoly

of

academic

specialists; some

of

the

most interesting and original

work

on the soul took place outside university walls,

particularly

after

1500,

when printing acted dramatically to expand the European intellectual

community.

Of

all the groups mentioned above, the contribution

of

the

humanists to

psychological discussion in the Renaissance was the most far-reaching,

10.

Nifo

1559 (In librum collectanearum prooemium) - a

position

eliminated

in the

preface

to the

later

Commentaria.

11.

See J. Zabarella 1606, pp. 21-2 (1,

text

2); F.

Piccolomini

1596, f. 7

r

(Introductio, cap. 7).

12.

Di Napoli 1963.

13.

University Records 1944, p. 279. The

association

was particularly

strong

in Italy,

where

medicine

and

philosophy

were

taught in the

same

faculty and

often

by the

same

people:

Kristeller

1978;

Siraisi

1981,

pp. 119-39

an

d ch. 6. On

Paris

and

Northern

Europe, see Kibre 1978.

Physicians

were

especially

important

as

commentators

on the

more

physiologically

oriented

Parva naturalia and

animal

books.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

458

Psychology

although also the least direct. Most humanists had little interest in technical

philosophy, but they called for

a

general

return

to the sources

of

the classical

tradition and to the study of Greek. Lamenting in

particular

the

'corruption'

of Aristotle's elegant style by incompetent medieval

translators,

they embarked on a massive programme of

editing

and

retranslating

his works that was to pave the way for a new approach to De

anitna

and to Aristotelian philosophy in general.

14

De

anima,

which had

previously circulated in the thirteenth-century Latin version

of

William of

Moerbeke, was retranslated twice during the fifteenth century, by the

Byzantine emigres George of Trebizond, who

followed

the traditional

word-for-word method, and

Johannes

Argyropulos, who was inspired by

the humanistic ideal of elegant

Latin.

It was translated at least

five

more

times into Latin during the sixteenth century and twice into Italian.

15

By

the middle

of

the sixteenth century the

Parva

naturalia,

too, had appeared in

multiple new translations, together

with

the Aristotelian books on

animals.

16

Not all these translations had the same influence. Some went through

only one edition. Others, notably the elegant Ciceronian versions of

Perion and Grouchy, who went so far as to change the title of De

anitna

to

De

animo,

attracted

a

wide

audience among humanistically educated lay

readers.

Academic philosophers, however, had different requirements;

embedded in a

long

tradition of Latin discourse, they needed a stable

technical vocabulary and favoured those new versions

—

Argyropulos' De

anima,

for example, and Vatable's

Parva

naturalia

— that managed to

combine a more up-to-date style

with

the medieval terminology. Thus

although Argyropulos' text became the standard new translation used by

academic

philosophers, the old version of Moerbeke often accompanied it

in De

anima

commentaries from as late as the second half of the sixteenth

century.

17

14.

Schmitt

1983a,

pp.

64-88;

Garin 1951; Platon et Aristote 1976, pp.

359-76

(Cranz).

15.

The

sixteenth

century

Latin

translators

included

Pietro

Alcionio

(first

edition

154.2),

Gentian

Hervet

(1544),

Joachim

Perion

(i549>

with

Nicolas

Grouchy's

revisions

1552),

Michael

Sophianus

(1562)

and

Giulio

Pace

(1596).

The

Italian

translators

were

Francesco

Sansovino

(1551) and

Antonio

Brucioli

(1559).

For

more

information

see

Minio-Paluello

1972, § 14; Platon et Aristote 1976, pp.

360-6

(Cranz); Cranz and

Schmitt

1984, pp. 165-7.

16.

Translators

of the Parva naturalia

included

Francois

Vatable

(first

edition

1518),

Alcionio

(1521),

Juan

Gines

de

Sepulveda

(1522),

Niccolo

Leonico

Tomeo

(1523),

Nifo

(1523)

and

Perion

(1550,

with

Grouchy's

revisions

1552). The

most

important

translator

of the

animal

books

was the

fifteenth-century

Greek

Theodore

Gaza, who

worked

on De generatione animalium, Historia

animalium and Departibus animalium. For

more

information

see Cranz and

Schmitt

1984, pp. 201-12,

167-8, 175-6, 177-8, 201;

Schmitt

1983a,

p. 85.

17.

See Philosophy and Humanism 1976, pp. 127-8 (Cranz); Platon et Aristote 1976, pp.

362-5

(Cranz);

Cranz 1978, pp. 177-8. On the

terminological

inadequacies

of the

Perion-Grouchy

translation

in

particular,

see

Schmitt

1983a,

pp.

76—9.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The

concept

of

psychology

459

Academic

psychology was also influenced by the new availability of the

Greek

text of Aristotle, first published in the Aldine edition of Aristotle's

Opera

omnia

(1495-8).

The psychological works were reprinted as

part

of

the

Opera

eight times over the course of the sixteenth century,

18

also

appearing frequently in separate editions, with or without Latin transla-

tions. During this same period,

a

number

of

universities established chairs to

teach

Aristotle in the original. In this way, we see the gradual emergence

during the Renaissance

of

the historical Aristotle, who called for philologi-

cal

and historical study as

well

as philosophical analysis. This new approach

to

Aristotle bore fruit in the writing on De

anima

by Francesco Vimercato

and,

above all, Giulio

Pace.

19

Even

more important for Renaissance psychology was the humanist

rediscovery,

translation and publication of the Greek commentaries on

Aristotle's psychological works. Averroes had cited them often, and

Thomas

Aquinas had access to some in

rare

medieval translations, but at the

beginning of the fifteenth century they were generally known only by

name

or indirectly.

20

The first to appear in print, in Ermolao

Barbaro's

Latin

translation, was the

paraphrase

of

De

anima

by Themistius.

21

Fourteen

years

later, in

1495,

Barbaro's

compatriot Girolamo Donato published his

own translation of Alexander of Aphrodisias' De

anima.

22

The two other

major

commentaries on De

anima,

that by Simplicius and that attributed to

Philoponus, did not appear in Latin until the

1540s,

although they had been

used in the Greek several decades earlier by Italian writers such as Giovanni

Pico

and Agostino

Nifo.

23

To these works we should also add Alexander's

commentary

on De

sensu

and a related work, the

Metaphrasis

in

Theophrastum

De

sensibus

of Priscianus Lydus, which became

newly

and

more

widely

available during the same period. All

of

these works served as

guides to the new Greek Aristotle and represented a significant body

of

new

ideas and interpretations for writers on psychology. Themistius and

Alexander,

for example, figured prominently in the Renaissance debates on

18.

Cranz and

Schmitt

1984, p. 165.

19.

Vimercato 1543; for Pace see

Aristotle

1596a and

Schmitt

1983a,

pp. 37-41.

20. Nardi 1958, pp.

365~4

20

-

F°

r

the

medieval

translations

see

Themistius

1957 and

Philoponus

1966.

For

more

details

on the

transmission

and

reception

of the Greek

commentators

in the Middle Ages

and

Renaissance

see Cranz 1958; Catalogus translationum

i960—,

1, pp. 77—135 and 11, pp. 411—22

(Alexander of Aphrodisias); m, pp.

75-82 (Priscianus

Lydus); Mahoney 1982.

21.

Themistius

1481;

first

Greek

edition,

Themistius

1534.

22. Alexander of

Aphrodisias

1495;

another

translation

of the

second

book

appeared

in 1546. The

first

Greek

edition

is in

Themistius

1534. See Averroes 1953, pp.

393-4.

23.

Simplicius

1543,

with

a

second

translation,

Simplicius

1553;

first

Greek

edition

1527; see, in

general,

Nardi 1958, pp.

373-442.

Philoponus

1544a, 1544b;

first

Greek

edition,

Philoponus

1535. The

real

author

of the

commentary

attributed

to

Philoponus

was apparently

Stephanus

of Alexandria:

Blumenthal

1982.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Psychology

the unity of the intellect and the immortality of the soul,

while

Simplicius

and Philoponus aided those who

wished

to reconcile Aristotle to

Neoplatonism and Christian dogma respectively.

Most far-reaching of all, however, humanist scholars began to recover

and disseminate lost works of classical philosophy from outside the

Aristotelian tradition. The most influential such sources for psychology

were the dialogues of

Plato,

especially the

Republic,

Timaeus

and

Phaedrus,

and a number of Neoplatonic treatises: Plotinus'

Enneads

(above all book

iv),

Iamblichus' De mysteriis, and Synesius' De insomniis

24

These works

proposed radically un-Aristotelian models for basic psychological phenom-

ena

—

vision, for example, and intellection

—

and injected

a

new magical and

theurgic

element into philosophical speculation on the soul. To them we

should also add the

newly

discovered

Enchiridion

of the Greek Stoic

Epictetus,

which went through countless editions after

1497,

25

and two

works from the sceptical tradition: Cicero's

Académica

and the Outlines of

Pyrrhonism

of Sextus Empiricus.

26

The first gave new emphasis to the

emotions, which had played a subordinate

part

in scholastic psychology,

while

the last two discussed sense deception and cognitive

error

in a way

that

challenged fundamental Aristotelian assumptions.

This influx of new material had a dramatic effect on psychology. In the

first place, it focused attention on the actual text

of

Aristotle,

as

philosophers

of

the soul from the late fifteenth century onwards struggled to strip away

medieval Latin and Arabic accretions in order to recapture the pristine

doctrine,

to discover what Aristotle actually said and meant. Those most

accomplished in Greek engaged in sophisticated exercises of philological

reconstruction,

as in Giulio Pace's commentary on De

anima

or Simone

Simoni's on De

sensu.

27

And even

less

historically oriented writers, from

Lefévre

d'Étaples to

Jacopo

Zabarella, produced a purified and

simplified

reading

of

Aristotle,

rejecting doctrines, such as that

of

the 'internal senses',

that

revealed themselves as later interpolations.

28

These efforts at purifica-

tion were not always successful. Immersed in the earlier interpretations,

Renaissance philosophers were unable to reject them entirely. Frequently

they even introduced new layers

of

their

own, such as the Neoplatonic

veil

derived from their reading of Themistius, Simplicius and Priscianus

24. Marsilio

Ficino's

Latin

translations

of

these

works

were

published

in the

1490s

and

reprinted

frequently

in the

sixteenth

century.

25. The

most

influential

Latin

translation

was that of Angelo

Poliziano.

By 1560 the work had

also

appeared

in German,

Italian

and French; see the bibliography of

editions

in Oldfather 1927, 1952.

26. See

Schmitt

1983c.

27. Platón et Aristote 1976, pp.

364-5

(Cranz);

Schmitt

1983a,

pp. 81-5.

28. See, e.g., Humanism in

France

1970, pp.

132-49

(Rice)

on Lefévre d'Étaples.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The

concept

of

psychology

Lydus.

29

Nonetheless, we can see an increased interest in and sensitivity to

the intentions of Aristotle in a

wide

range of late fifteenth- and sixteenth-

century

writers on psychology.

In the second place, the new scholarship vastly expanded the range of

philosophical reference. Renaissance writers on psychology had access to

the works of a

wide

variety of commentators on Aristotle - commonly

divided into the

Latins,

the

Arabs

and the

Greeks

- among whom they could

pick and choose according to their own philosophical interests and

commitments. Those eager to reconcile Aristotle with Christianity, for

example, preferred the authority of the first,

while

those more influenced

by the humanist agenda emphasised the last.

Furthermore,

sixteenth-

century

philosophers were no longer confined to the works

of

Aristotle and

his followers, but could confront their doctrines with the radically different

views

of classical philosophers from other schools. Most academic

philosophers ended up by confirming the old doctrines with only minor

shifts in emphasis, but others — Ficino among the Neoplatonists, for

example, or Montaigne among the sceptics - moved in significantly new

directions.

Already

in the second half of the fifteenth century we can see

signs

of

these changes outside the universities.

From

the

1490s

onwards the new

ideas, sources and approaches appeared with increasing frequency in the

work

of scholastic writers

like

Agostino

Nifo

and Pietro Pomponazzi in

Italy,

or the circle of Lefevre d'Etaples in

France

—

writers who in other

respects

had strong ties to the earlier tradition. The point of real rupture

came

in the

1520s.

Before this time

European

presses had continued to print

the psychological works

of

fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Latin writers

untouched by humanist influences, even

as

they turned out new translations

and editions of classical philosophers. Far from fading, the influence of

earlier

commentators such as Thomas Aquinas, Albertus Magnus, Duns

Scotus and William of Ockham continued to grow throughout the

fifteenth century, as self-conscious 'schools' or

viae

of philosophers in the

various universities struggled to promote and elaborate their interpreta-

tions.

30

About

1525,

however, the general interest in high and late medieval

29. Mahoney 1982; Nardi 1958.

30. The

main

self-proclaimed

schools

in

this

period

included

the via moderna

('nominalists'

and

followers

of Ockham) and the via antiqua, the

latter

further

subdivided

into

Thomists, Albertists and

Scotists;

philosophers

were

also

identified

as 'Averroists', a

term

much

abused

by

historians.

This

situation

was

most

pronounced

in

northern

universities,

where

the viae

often

had

their

own

colleges,

but it

prevailed

to a

lesser

extent

in Italy as

well:

see Ritter

1921-2,11;

Antiqui und Moderni 1974, pp.

439-83

(Gabriel);

Meersseman

1933-5;

Renaudet

1953, pp. 93-101; and - on Italy -

Schmitt

1984,

§

vni, pp. 121-6;

Kristeller

1974, pp. 45-55; Poppi 1964; Mahoney 1974, 1980; and Matsen 1975.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

462

Psychology

psychology saw a marked decline. The printing history of Paul of Venice

mirrors

that of

a

host of popular fifteenth-century authors:

between

1475

and 1525 his commentary on De

anima

was

published

five

times and his

Summa naturalium, ten; no more

editions

appeared after

1525.

31

The reasons

for this break

seem

clear. The 'barbarous' Latin prose of the earlier

commentators grated on sixteenth-century

ears,

while

their ignorance of

the new Greek material rendered them

obsolete

in tone and content.

We

should

not overstate the break

with

the past. Medieval assumptions,

problems and terminology continued to permeate sixteenth-century

psychology. Indeed, we see a revival of interest in certain aspects of the

medieval tradition, as many philosophers reacted against the humanists'

historical and

philological

reading of Aristotle in favour of a more

substantive approach.

32

In Italy, on the one hand, this revival gave new

prominence to Averroes and extended to his main medieval expositor, the

fourteenth-century

Jean

de Jandun.

33

In Spain and Portugal, on the other,

the revival crystallised around the figure

of

Thomas Aquinas and reflected

the rehabilitation of thirteenth-century

philosophy

under the auspices of

the Counter-Reformation. The Jesuits quickly accepted Thomas as the

prime interpreter of Aristotle. His writings on psychology, together

with

those

of

his late medieval interpreters, were

often

reprinted after the

middle

of

the century, and their

influence

spread

even

more

widely

through the

commentaries put out by the Jesuit College at Coimbra and the College of

the Discalced Carmelites at Alcalá.

34

Neither the Italian Averroism nor the

Counter-Reformation Thomism of the later sixteenth century

should

be

seen

as medieval throwbacks; both incorporated the

philological

sophistica-

tion

of the humanists and their appreciation of the powers of printing, as

well

as a

good

many

of

the new Greek sources. In this way, both confirmed

the break

with

the later fourteenth and

fifteenth

centuries.

It

is this abrupt confluence of classical and medieval currents that

lends

Renaissance psychology its drama and

uniqueness.

From

1490 on, writers

on the

soul

struggled to accommodate the new materials of the classical

31.

Lohr 1972a, pp. 317-19- This

chronological

break

appears

in all

areas

of

Aristotelian

philosophy

and

in all

parts

of

Europe

with

the

exception

of

Poland,

which

remained

a

pocket

of

medieval

Aristotelianism

even

after

1525; see Cranz and

Schmitt

1984, pp.

vii-ix;

Schmitt

1983a,

pp. 52-3.

32.

Schmitt

1984, §

viii,

p. 127;

1983a,

p. 82.

33. Philosophy and Humanism 1976, pp. 116-28 (Cranz);

Schmitt

1984, § vm. On

Jandun,

see Lohr 1970,

pp. 213-14.

34. Cranz 1978.

Among

the

most

influential

of the

earlier

Thomists

writing

on

psychology

were

Dominicus

de

Flandria,

Cardinal Cajetan and

Crisostomo

Javelli,

all

active

in the

decades

around

1500.

Duns

Scotus

benefited

from

the

revival

of

thirteenth-century

Latin

philosophy

and

theology,

as did, for

example,

Durandus

a S.

Porciano,

but to a

lesser

degree

than

Thomas.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The concept

of

psychology

revival and the new religious imperatives of the Protestant and Catholic

reformations.

The period was a complicated and confused one, and the

diversity

of

the philosophical materials, collected from different schools and

traditions,

makes it burdensome to exhume the position

of a

given

author.

This may have been the reason why psychological discussion declined in

manuals and textbooks such as the Coimbra commentaries. It is certainly

the reason why philosophers after Descartes attempted to circumvent the

whole

problem and why modern attempts to reconstruct Renaissance

debates remain so tentative, fragmentary and incomplete.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

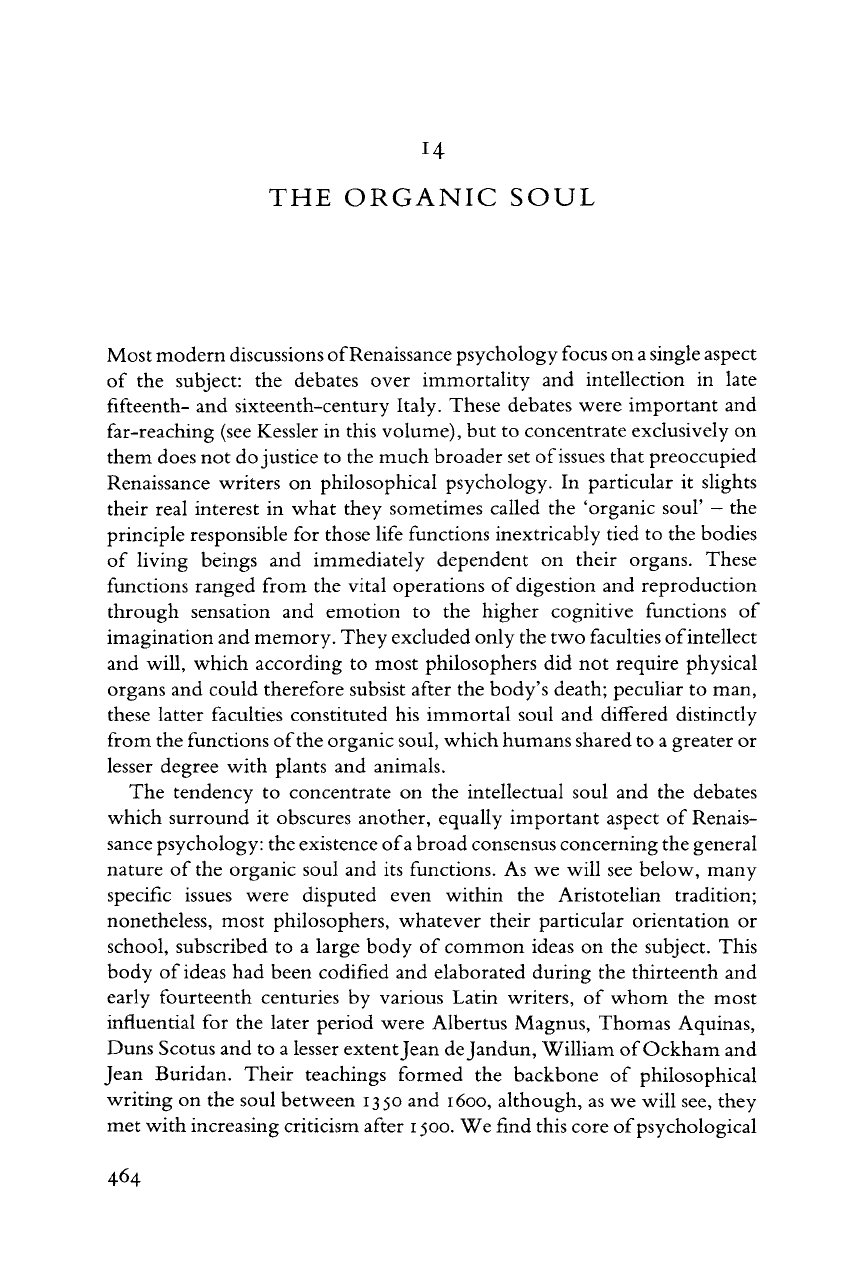

THE

ORGANIC SOUL

Most modern discussions

of

Renaissance psychology focus on

a

single

aspect

of

the subject: the debates over immortality and intellection in late

fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Italy. These debates were important and

far-reaching

(see Kessler in this volume), but to concentrate exclusively on

them does not do justice to the much broader set

of

issues

that preoccupied

Renaissance writers on philosophical psychology. In

particular

it slights

their

real

interest in what they sometimes called the 'organic soul' - the

principle responsible for those

life

functions inextricably tied to the bodies

of

living

beings and immediately dependent on their organs. These

functions ranged from the vital operations of digestion and reproduction

through sensation and emotion to the higher cognitive functions of

imagination and memory. They excluded only the two faculties

of

intellect

and

will,

which according to most philosophers did not require physical

organs

and could therefore subsist after the body's death; peculiar to man,

these

latter

faculties constituted his immortal soul and differed distinctly

from

the functions

of

the organic soul, which humans shared to a

greater

or

lesser degree with plants and animals.

The

tendency to concentrate on the intellectual soul and the debates

which surround it obscures another, equally important aspect of Renais-

sance

psychology: the existence

of

a

broad consensus concerning the general

nature

of the organic soul and its functions. As we

will

see below, many

specific

issues

were disputed even within the Aristotelian tradition;

nonetheless, most philosophers, whatever their

particular

orientation or

school, subscribed to a large body of common ideas on the subject. This

body of ideas had been codified and elaborated during the thirteenth and

early

fourteenth centuries by various Latin writers, of whom the most

influential for the later period were Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas,

Duns Scotus and to a lesser extent

Jean

de

Jandun,

William

of

Ockham

and

Jean

Buridan. Their teachings formed the backbone of philosophical

writing on the soul between

1350

and 1600, although, as we

will

see, they

met with increasing criticism after

1500.

We

find

this

core

of

psychological

464

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The

organic

soul

465

opinion not only in specialised commentaries and monographs but also -

and perhaps even more clearly

—

in the general textbooks used to introduce

university students to academic philosophy. Among these the most

influential was probably the

Margarita

philosophica

(Philosophic

Pearl),

written in the

1490s

by the German Carthusian Gregor Reisch.

1

In both

sources and their general

structure,

books x and xi

of

this work testify to the

continuing influence

of

medieval Latin writers on Renaissance psychology.

At

the same time they provide an excellent picture of the ideas concerning

the soul accepted by most philosophers in the years before 1500, and by

many to the end of the sixteenth century.

2

THE

ARISTOTELIAN KOINE

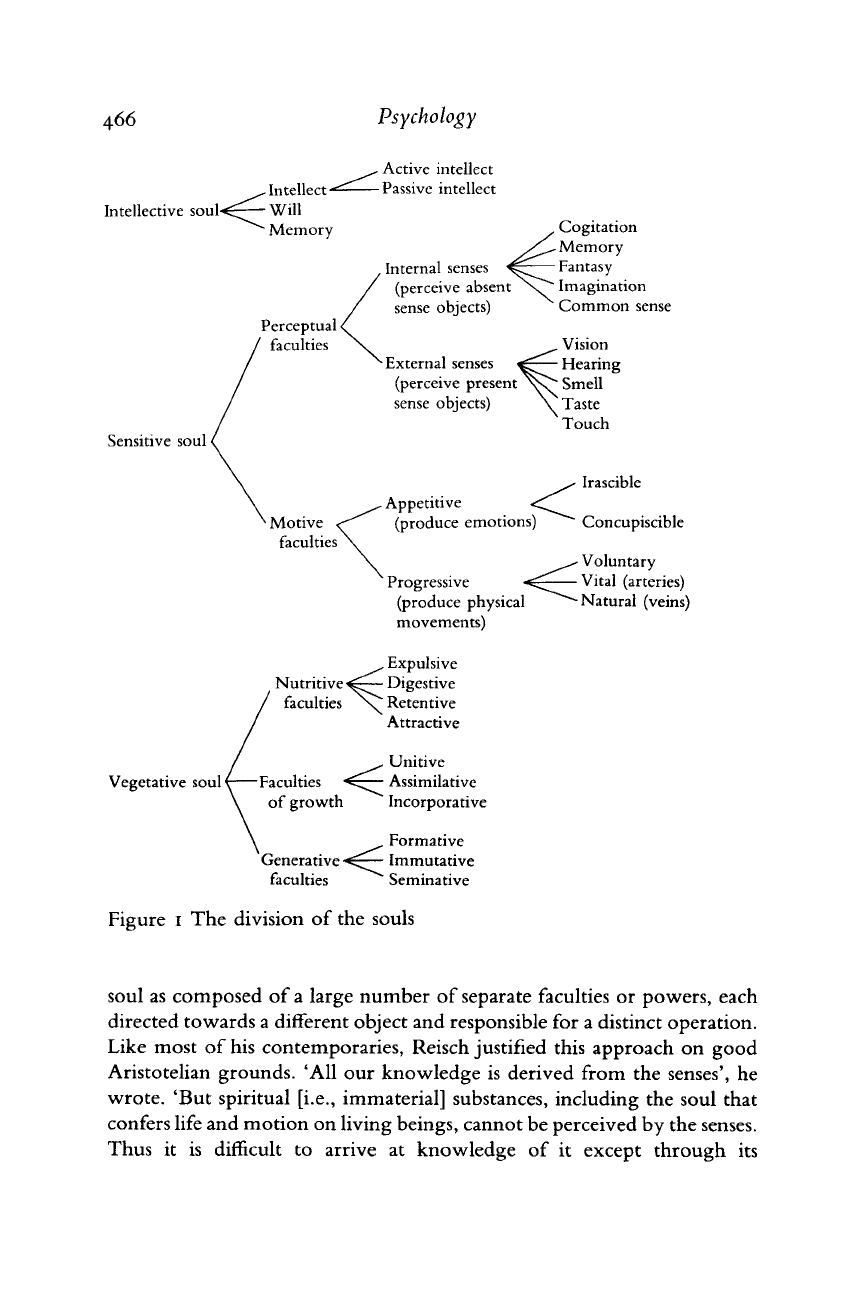

Reisch's psychology,

like

that of the tradition he represented, was a

synthesis of ideas from many different sources. Many derived from the

works

of

Aristotle.

Some had their roots in other classical traditions, such as

Greek

Neoplatonism and Galenic medicine,

while

others grew out of the

works of early Christian writers such as St Augustine and Nemesius of

Emesa.

Still others

—

and this group was in some respects dominant

—

were

the creation of medieval Arabic writers on Aristotelian philosophy, of

whom the most important were Avicenna and Averroes. It is

a

testimony to

the enormous ingenuity of the Latin writers of the thirteenth and early

fourteenth centuries that they had managed to

weld

this collection into a

persuasive explanatory system, which for the most

part

they attributed to

Aristotle himself. As inherited by Reisch, this system included a number of

elements drawn directly from De

anima

and the

Parva

naturalia,

together

with many others that Aristotle

would

not have recognised and probably

would

have rejected.

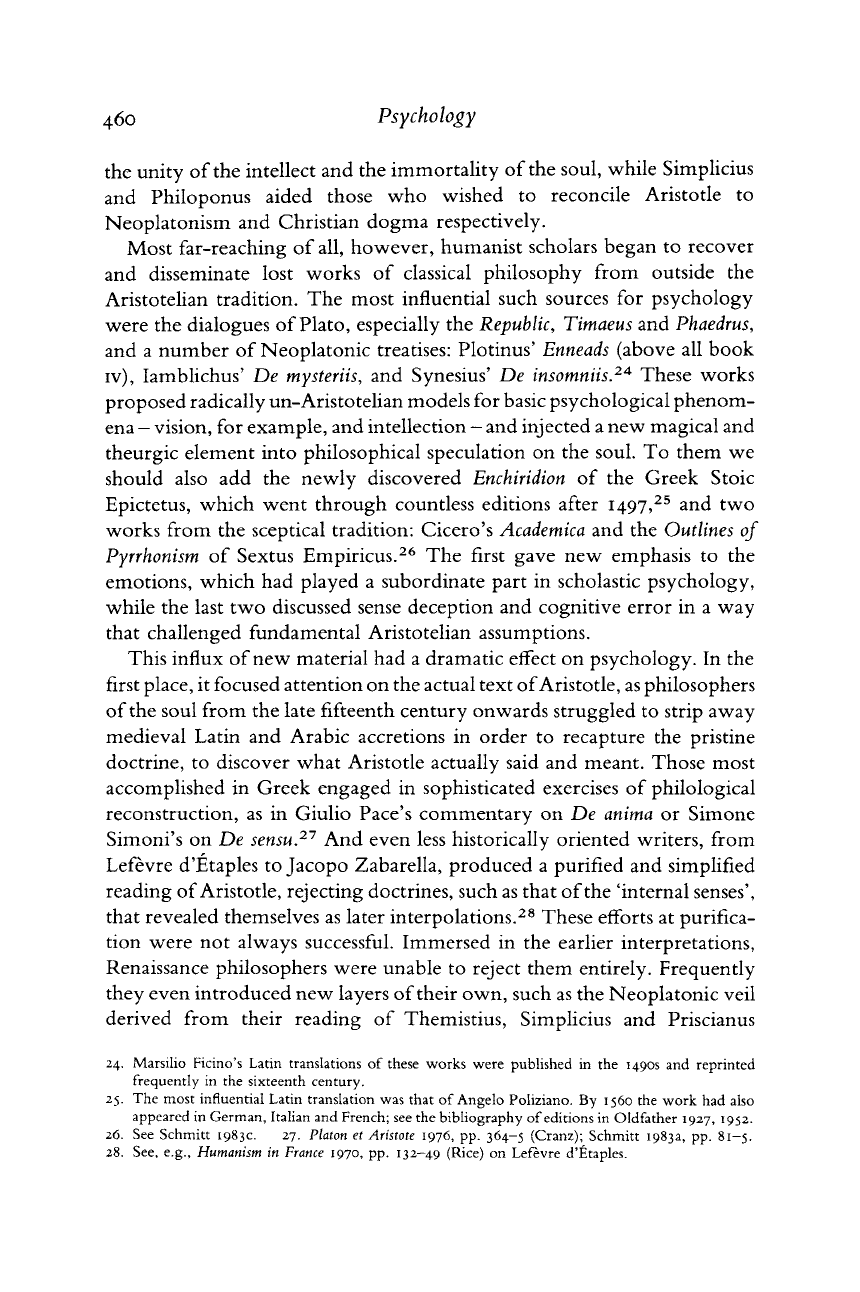

Reisch's psychology was above all

a

faculty psychology. He described the

1.

Reisch

1517. On

this

work and its

author,

see Srbik 1941, Miinzel 1937, and

Geldsetzer's

introduction

to the 1973

reprint

of

Reisch

1517. The Margarita,

which Reisch

expanded

and

revised

in

four

successive

editions

between

1503 and 1517, was

printed

at

least

ten

times

in

full

and

several

times

in part

over

the

course

of the

sixteenth

century.

It

also

appeared

in French and

Italian

translations.

Other

such

textbooks,

of

widely

varying

orientations,

include

Paul of

Venice

1503;

Hundt 1501; Vives 1538; and

Melanchthon

1834-60,

xm,

cols.

5-178 (Liber de anima). On the use of

textbooks

as

introductions

to

Aristotelian

philosophy,

see Grabmann 1939; Platon et Aristote 1976,

pp. 147-54

(Reulos);

and on a

slightly later

period,

Reif 1969; see

also

Schmitt

in

this

volume.

2. The

main

exception

to

this

statement

regards

philosophers

with

a

pronounced

nominalist

or

Ockhamist

orientation,

who

identified

themselves

with

the

so-called

via moderna. As a

follower

of

the via antiqua,

Reisch

differed

from

the moderni on a

number

of particular

issues,

including

the

relation

of the

soul

to its

powers,

as

discussed

below.

On the

distinction

between

moderni and antiqui

see Antiqui und Moderni 1974, esp. pp. 85-125 (N. W. Gilbert), and bibliography

therein.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

466

Psychology

Intellective soul <—Will

<

Intellect-

Memory

Sensitive soul

Perceptual

<

faculties

Motive

faculties

Vegetative souH

Nutritivem

faculties

-Faculties

of

growth

.

Active intellect

-Passive intellect

,

Internal senses

(perceive

absent

sense objects)

v

External

senses

(perceive

present

sense objects)

Cogitation

Memory

Fantasy

Imagination

Common sense

.

Vision

•

Hearing

'

Smell

*

Taste

Touch

Irascible

*

Appetitive

(produce

emotions) Concupiscible

^

Progressive

(produce

physical

movements)

,

Expulsive

•

Digestive

*

Retentive

Attractive

Unitive

Assimilative

Incorporative

Voluntary

Vital

(arteries)

Natural

(veins)

<

Formative

Immutative

racuities

Seminative

Figure

i The division of the souls

soul as composed of

a

large number of

separate

faculties or powers, each

directed

towards a different object and responsible for a distinct operation.

Like

most of his contemporaries, Reisch justified this approach on good

Aristotelian grounds. 'AH our knowledge is derived from the senses', he

wrote.

'But spiritual [i.e., immaterial] substances, including the soul that

confers

life

and motion on

living

beings, cannot be perceived by the senses.

Thus

it is difficult to

arrive

at knowledge of it except through its

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008