The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13: Republican China 1912-1949, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE MIDDLE YEARS I939-I943

68l

grimmer picture. By 1942, 90 per cent

of

the plains bases were reduced

to guerrilla status or outright enemy

control.

In the mountainous T'ai-yueh

district

of

the Chin-Chi-Lu-Yii base,

a

cadre admitted that ' not

a

single

county was kept intact and the government offices of all its twelve counties

were exiled

in

Chin-yuan'.

84

All

twenty-six county seats occupied

in

the wake of the Hundred Regiments righting were lost.

Although Japanese pacification was aimed mainly at the 8RA, this was

not always the case. Nationalist forces with whom the Japanese had been

unable to reach ' understandings' were attacked also, partly

to

free more

forces

for

anti-Communist action, partly

to

keep pressure

on

Chiang

Kai-shek,

and

partly

to

have more successes

to

report.

The

most

significant

of

these actions took place during

the

spring

of

1941

in

southern Shansi, when over twenty divisions under General Wei Li-huang

were pushed south

of

the Yellow River (the Battle

of

the Chung-t'iao

Mountains,

or

the Chugen campaign). Almost

as

important were later

actions in Shantung against Yii Hsueh-chung and Shen Hung-lieh. These

cleared additional areas

for

Communist penetration once Japanese and

puppet forces withdrew;

the

consequences became fully evident when

Japanese pressure

on

the Communists moderated during the last phase

of the war.

Japanese consolidation

in Central China

The China Expeditionary Army followed

a

different pattern from that

pursued

by the

North China Area Army. Although

the

total forces

available

to

the CEA were larger than those of the NCAA

(c.

300,000

in

Central China, and another 165,000

in

the south),

a

smaller proportion

was devoted

to

pacification, perhaps 50,000

to

75,000. Most

of the

remainder of the CEA was deployed opposite Nationalist units in Hupei,

Hunan

and

Kiangsi.

On the

other hand, larger and presumably more

effective puppet forces could be employed

in

the Lower Yangtze region

because of its proximity to the Nanking regime of Wang Ching-wei.

Japanese

and

puppet forces concentrated

on the

area

of

greatest

strategic importance to them: the Nanking-Shanghai-Hangchow triangle,

a part

of

8RA tosses was due to direct combat casualties. Other factors included reassignment

of some regulars

to

service as guerrilla forces (to strengthen the latter,

to

merge more closely

with the local population, to reduce burdens of

troop

support); elimination of inferior or disabled

soldiers; and desertion. One

CCP

document from late 1939 (presumably Chin-Ch'a-Chi) gave two

examples of desertion rates: 16-4% in 'one main force unit', and 20-8%

in'

one

newly established

guerrilla unit'. Desertion was particularly serious when a unit was moved out of its home area;

peasant-soldiers

in

the local forces often refused to leave. This was

yet

another motive for reducing

some full-time soldiers to militia status.

84

Warren Kuo,

History,

4.7

j.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

682 THE CHINESE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT, I937-1945

together with the region just north of the Yangtze River and east of the

Grand Canal. The Wuhan region, farther west, was also heavily pacified.

These efforts and a strong Nationalist presence in Hupei prevented Li

Hsien-nien and the N4A's 5 th Division from setting up

a

fully consolidated

base in the Ta-pieh Mountains until late in the war. But other areas in

Kiangsu, Anhwei and Honan were deemed less significant from either

a

military or economic viewpoint. Japanese forces maintained control over

major transportation routes in east-central China and over the major cities.

Occasional sweeps were sent through remoter areas. These were rather

easily evaded by N4A elements but inflicted serious damage on Chungking-

affiliated forces.

85

Not until the second half of 1941 did the Japanese begin serious

pacification in the Yangtze delta, with the adoption by General Hata

Shunroku of a plan to establish ' model peace zones'. This was a phased

programme in which carefully defined areas were to be brought under

ever tighter military, political and economic security. When one zone had

reached a certain level of development, an adjacent area would be added.

The first step was to carry out intense clearing operations in order to drive

out all resistors and begin with a clean slate. Tight boundary controls were

then enforced, using dense bamboo palisades or other defensive works.

Within the zone, local police undertook careful population registration,

and administrative personnel were assigned a comprehensive programme

of' self-government, self-defence, and economic self-improvement'. In the

most developed of the model peace zones, Japanese troop density reached

1*3 per sq. km., three and a half times larger than in North China. Harsh

coercion was applied as necessary. As a result, security within the model

peace zones in the northern Yangtze delta became quite good. Tax

revenues collected by agents of the Nanking regime went up sharply, as

did compulsory labour service. Japanese soldiers and well-known local

collaborators claimed, with

relief,

that they could come and go without

fear of ambush.

Yet even at their most successful, these efforts were not a general

solution to the problem of Chinese resistance, either Nationalist or

Communist. The model peace zones required so much manpower and

other resources that they were very limited in extent. By 1943, when such

efforts no longer had high priority, only a few such zones were classified

as having passed through all the planned phases, the remainder being

stalled in one or another preliminary stage. The only such effort well to

the north of the Yangtze was the late (February 1944) and almost

completely futile creation of a new province, Huai-Hai, with its capital

85

Ch'en Yung-fa,

IIO-II.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE MIDDLE YEARS I939-I943 683

at Lienyunkang. And even within the securest of the model peace zones,

both the Communists and the Nationalists were able to maintain a

continuing low-level presence.

Further reasons for the limited success and ultimate failure of

the

model

peace zones were that many tasks had sooner or later to be turned over

to the Chinese themselves, either Wang Ching-wei appointees or recruits

from the local populace. Both were the constant despair of the Japanese:

the former because of their incompetence, corruption and factional

disputes; the latter because they would do only what they felt compelled

to do or what was in their self-interest. In the end, the model peace zones

bore witness to the short-term and territorially limited effectiveness of

superior power. They also demonstrated that such a solution was no

solution at all across the vast breadth and population of 'occupied China'.

CCP

RESPONSES: SURVIVAL AND NEW POLICIES

The combined effects of friction and pacification confronted the Chinese

Communist Party with its most serious and prolonged crises of the

Sino-Japanese War. Ironically, these challenges were exacerbated because

Communist military and political expansion early in the war had often

stressed rapid growth at the expense of consolidation and deep penetration

of the villages. At the same time, after three good years, adverse weather

led to poor harvests in 1940 and

1941,

adding to already serious economic

problems. The CCP's responses to these challenges, begun in piecemeal

fashion, were as many-sided as the problems themselves. Some existing

policies were overhauled and adapted to new circumstances. Some new

policies were continued long after the immediate difficulties had been

overcome, while others were ad hoc, common sense measures to minimize

losses or gain new support. In retrospect the new pattern can be seen as

early as 1940. By 1942 it was in full swing. The Maoist leadership now

saw it as an integral whole.

Inseparable from the urgent practical tasks of this arduous period was

the definitive elevation of Mao Tse-tung as the supreme leader and

ideological guiding centre of the CCP. Between 1942 and 1944, the last

major elements were added to complete ' the thought of Mao Tse-tung',

and the last remnants of opposition to his primacy were removed or

silenced. From this time, at the latest, the movement bore the indelible

stamp of his policies and personality. The experience of these years shaped

the CCP. Like the Long March a decade earlier, the Yenan era took on

an independent existence - part history, part myth - capable of influencing

future events.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

684 THE CHINESE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT, I937-I945

New

policies

in

Shen-

Kan-

Ning

Economic

problems.

The principal economic changes in Shen-Kan-Ning

during the middle years of the war have already been mentioned: the end

of the Nationalist subsidy, the blockade, and poorer harvests than in the

years immediately preceding. These changes had profound, widespread

and enduring effects. They very nearly caused the economy of SKN

to collapse. Looking back on this period, Mao wrote in 1945: 'When [the

war] began we had food and clothing. But things got steadily worse until

we were in great difficulty, running short of grain, short of cooking oil

and salt, short of bedding and clothing, short of funds.'

86

The Nationalists' eonomic warfare deprived SKN of its principal source

of ' hard currency' and either cut off or greatly changed the terms of its

trade with other regions of unoccupied China. The party, government

and army bureaucracies together with large numbers of immigrants, made

the Border Region's resources, insufficient even in normal times, all the

more inadequate. The goal of

the

party, therefore, was to bring the region

as close as possible to economic self-sufficiency. Although full autarky

was impossible, considerable progress was eventually made. Meanwhile

economic conditions deteriorated rapidly.

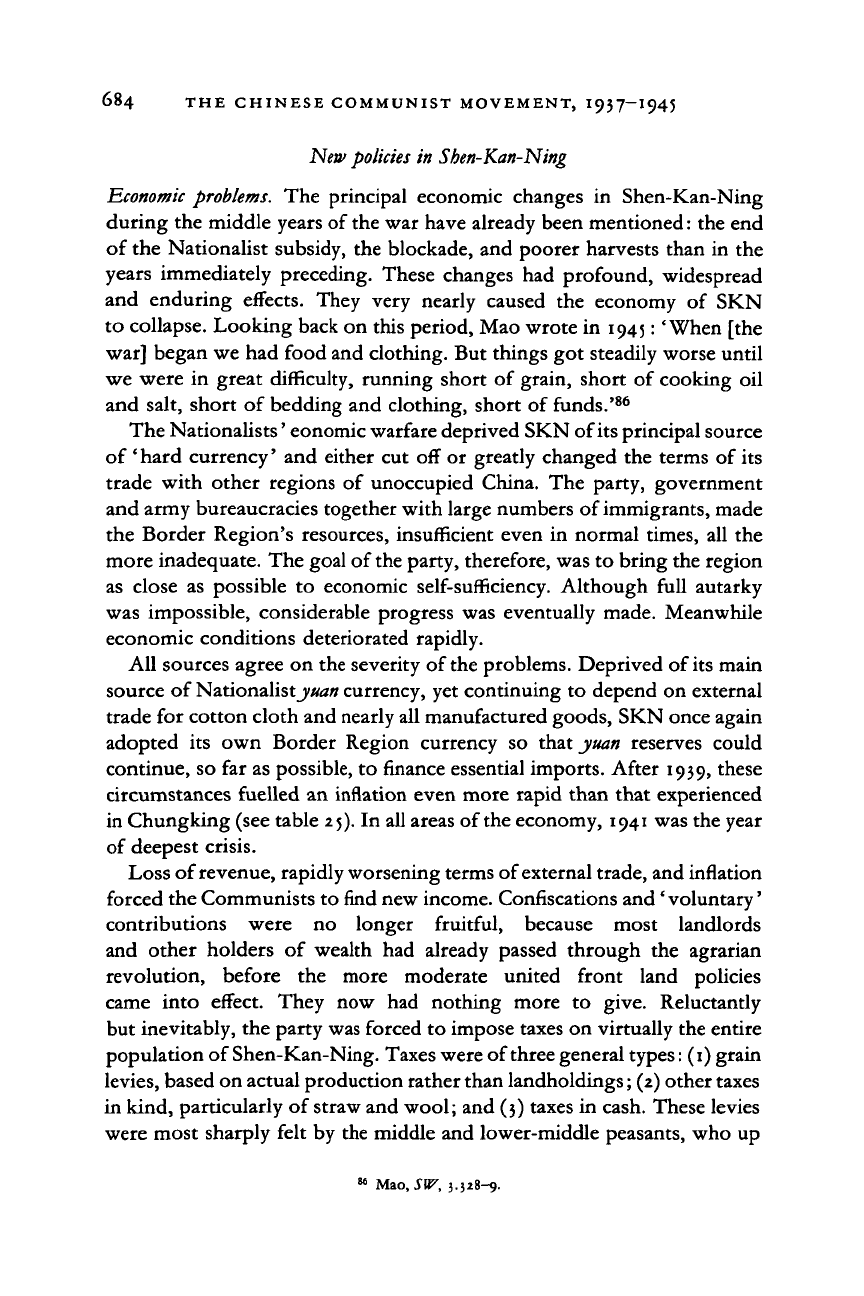

All sources agree on the severity of the problems. Deprived of

its

main

source of Nationalist yuan currency, yet continuing to depend on external

trade for cotton cloth and nearly all manufactured goods, SKN once again

adopted its own Border Region currency so that yuan reserves could

continue, so far as possible, to finance essential imports. After 1939, these

circumstances fuelled an inflation even more rapid than that experienced

in Chungking (see table 25). In all areas of

the

economy, 1941 was the year

of deepest crisis.

Loss of revenue, rapidly worsening terms of external trade, and inflation

forced the Communists to find new income. Confiscations and' voluntary'

contributions were no longer fruitful, because most landlords

and other holders of wealth had already passed through the agrarian

revolution, before the more moderate united front land policies

came into effect. They now had nothing more to give. Reluctantly

but inevitably, the party was forced to impose taxes on virtually the entire

population of Shen-Kan-Ning. Taxes were of three general types: (1) grain

levies,

based on actual production rather than landholdings; (2) other taxes

in kind, particularly of straw and wool; and (3) taxes in cash. These levies

were most sharply felt by the middle and lower-middle peasants, who up

86

Mao, SW, 3.328-9.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE MIDDLE YEARS I939-I943 685

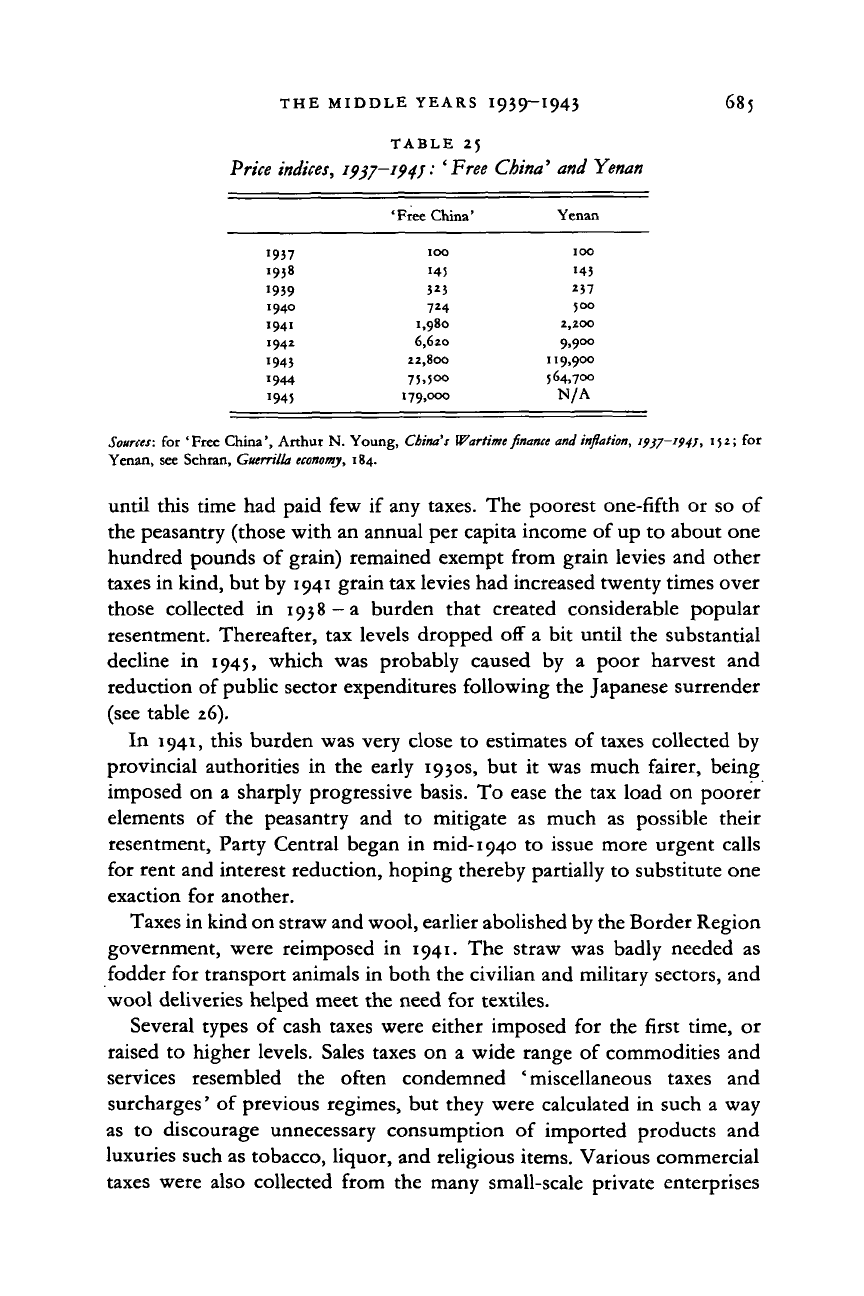

TABLE 25

Price

indices,

1937-194j: 'Free China' and Yenan

1937

1938

1959

1940

1941

1942

•94}

'944

1945

'Free China'

100

145

3*3

7*4

1,980

6,620

22,800

75>5°°

179,000

Yenan

100

143

*37

500

2,200

9,900

119,900

564,700

N/A

Sources:

for 'Free China', Arthur N. Young, China's Wartime

finance

and

inflation,

1937-194;,

152;

for

Yenan, see Schran,

Guerrilla

economy,

184.

until this time had paid few

if

any taxes. The poorest one-fifth

or

so of

the peasantry (those with an annual per capita income of up to about one

hundred pounds of grain) remained exempt from grain levies and other

taxes in kind, but by 1941 grain tax levies had increased twenty times over

those collected

in

1938 —a burden that created considerable popular

resentment. Thereafter, tax levels dropped off a bit until the substantial

decline

in

1945, which was probably caused

by a

poor harvest

and

reduction of public sector expenditures following the Japanese surrender

(see table 26).

In 1941, this burden was very close to estimates of taxes collected by

provincial authorities

in

the early 1930s, but

it

was much fairer, being

imposed on

a

sharply progressive basis. To ease the tax load on poorer

elements

of

the peasantry and

to

mitigate

as

much

as

possible their

resentment, Party Central began

in

mid-1940

to

issue more urgent calls

for rent and interest reduction, hoping thereby partially to substitute one

exaction for another.

Taxes in kind on straw and wool, earlier abolished by the Border Region

government, were reimposed

in

1941. The straw was badly needed

as

fodder for transport animals in both the civilian and military sectors, and

wool deliveries helped meet the need for textiles.

Several types

of

cash taxes were either imposed

for

the first time,

or

raised

to

higher levels. Sales taxes on

a

wide range

of

commodities and

services resembled

the

often condemned 'miscellaneous taxes

and

surcharges' of previous regimes, but they were calculated in such a way

as

to

discourage unnecessary consumption

of

imported products and

luxuries such as tobacco, liquor, and religious items. Various commercial

taxes were also collected from the many small-scale private enterprises

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

686

THE CHINESE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT, I937-I945

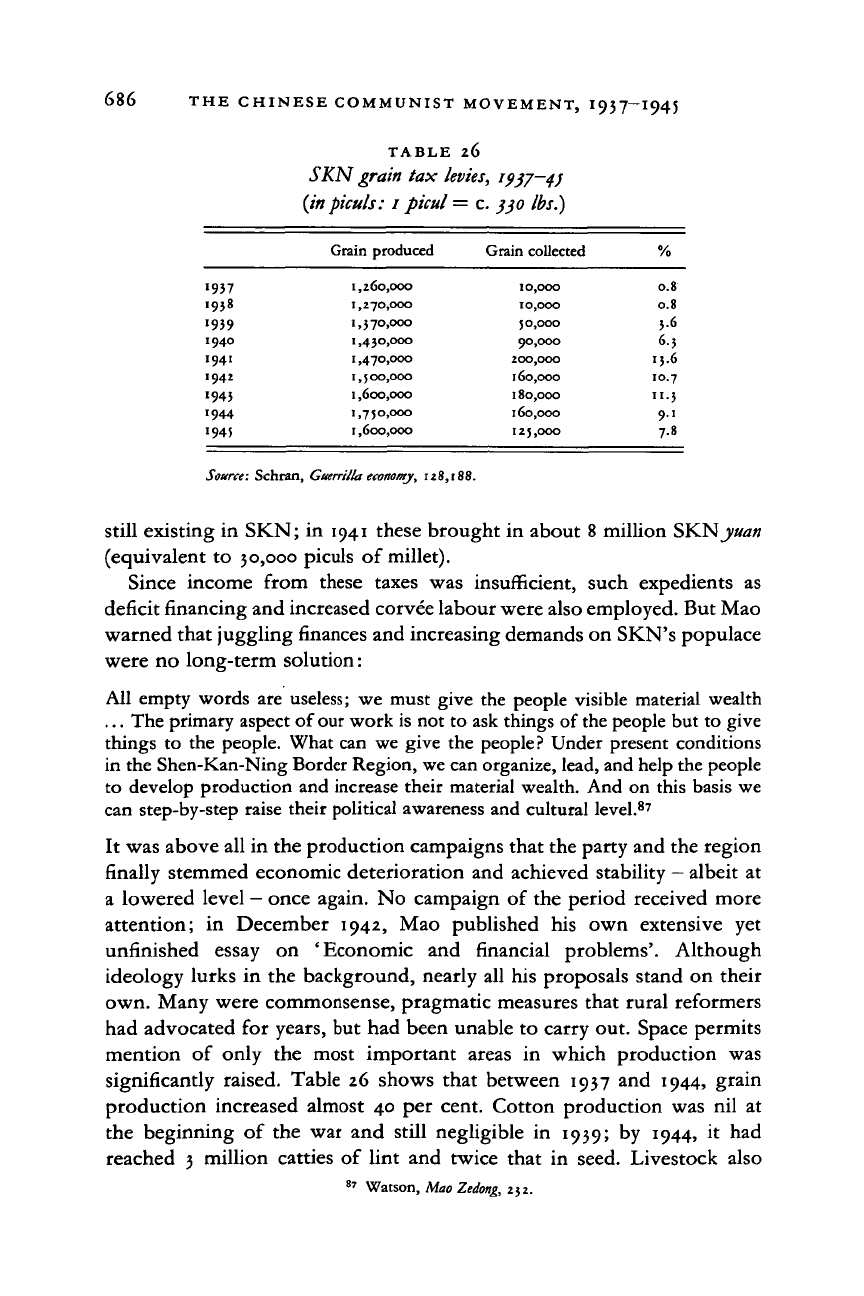

TABLE

26

SKN grain

tax

levies,

1937-4)

(inpiculs:

1

picul

=

c.

}$o lbs.)

'937

1938

•939

1940

1941

1942

1943

1944

1945

Grain produced

,260,000

,270,000

,370,000

,430,000

,470,000

,500,000

,600,000

,750,000

,600,000

Grain collected

10,000

10,000

;

0,000

90,000

200,000

160,000

180,000

160,000

125,000

%

0.8

0.8

3.6

6.3

13.6

10.7

11.3

9'

7.8

Source: Schran, Guerrilla

economy,

128,188.

still existing

in

SKN;

in

1941 these brought

in

about 8 million SKNjuan

(equivalent

to

30,000 piculs

of

millet).

Since income from these taxes

was

insufficient, such expedients

as

deficit financing and increased corvee labour were also employed. But Mao

warned that juggling finances and increasing demands on SKN's populace

were

no

long-term solution:

All empty words are useless; we must give the people visible material wealth

... The primary aspect of

our

work is not to ask things of

the

people but to give

things

to

the people. What can we give the people? Under present conditions

in the Shen-Kan-Ning Border Region, we can organize, lead, and help the people

to develop production and increase their material wealth. And on this basis we

can step-by-step raise their political awareness and cultural level.

87

It was above all in the production campaigns that the party and the region

finally stemmed economic deterioration and achieved stability

—

albeit

at

a lowered level

-

once again.

No

campaign

of

the period received more

attention;

in

December 1942,

Mao

published

his

own

extensive

yet

unfinished essay

on

'Economic

and

financial problems'. Although

ideology lurks

in

the background, nearly all his proposals stand

on

their

own. Many were commonsense, pragmatic measures that rural reformers

had advocated

for

years, but had been unable

to

carry out. Space permits

mention

of

only

the

most important areas

in

which production

was

significantly raised. Table

26

shows that between 1937

and

1944, grain

production increased almost

40 per

cent. Cotton production was

nil

at

the beginning

of

the war and

still negligible

in

1939;

by

1944,

it

had

reached

3

million catties

of

lint

and

twice that

in

seed. Livestock also

87

Watson,

Mao

Zedong,

232.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

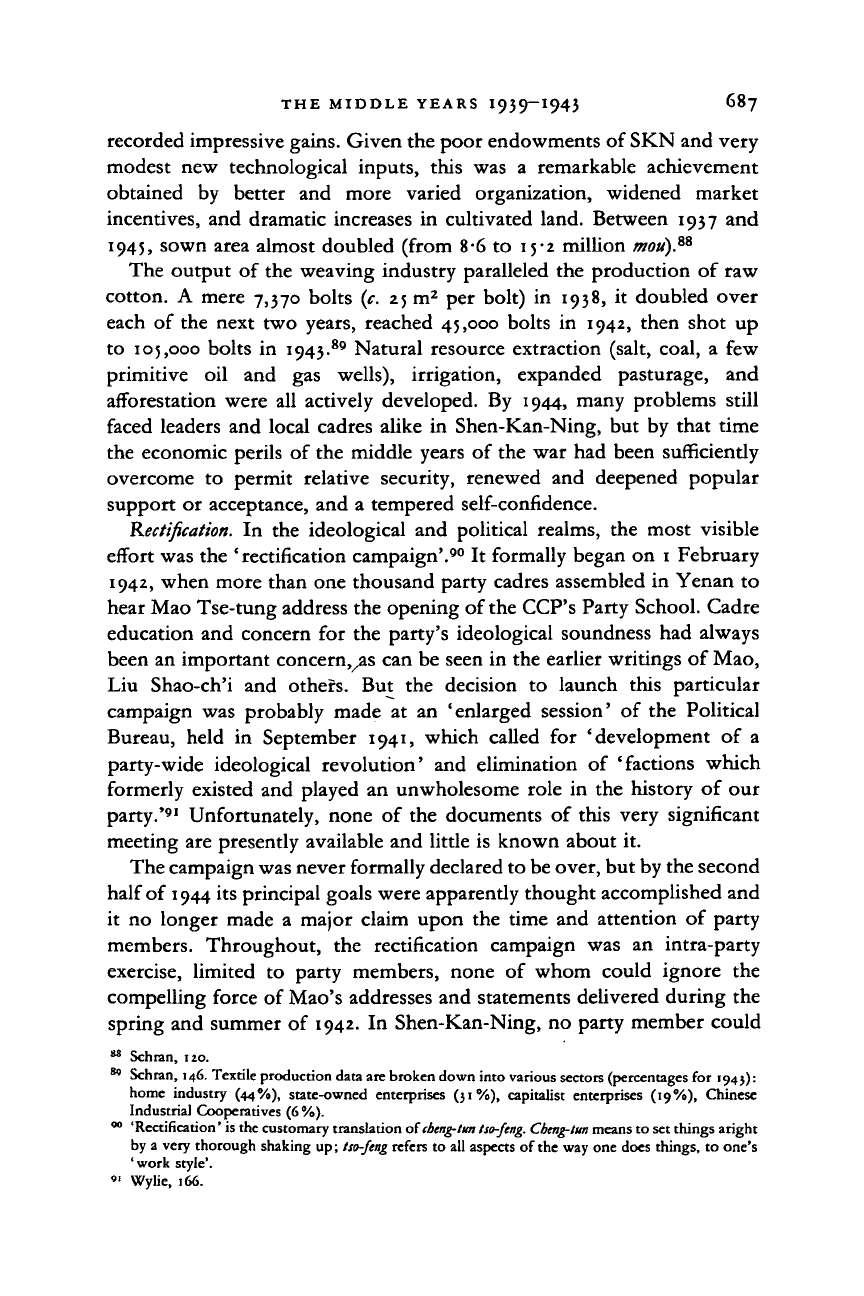

THE MIDDLE YEARS I939-I943 687

recorded impressive gains. Given the poor endowments of SKN and very

modest new technological inputs, this was a remarkable achievement

obtained by better and more varied organization, widened market

incentives, and dramatic increases in cultivated land. Between 1937 and

1945,

sown area almost doubled (from 8-6 to 152 million mou).

ss

The output of the weaving industry paralleled the production of raw

cotton. A mere 7,370 bolts (c. 25 m

2

per bolt) in 1938, it doubled over

each of the next two years, reached 45,000 bolts in 1942, then shot up

to 105,000 bolts in

1943.

89

Natural resource extraction (salt, coal, a few

primitive oil and gas wells), irrigation, expanded pasturage, and

afforestation were all actively developed. By 1944, many problems still

faced leaders and local cadres alike in Shen-Kan-Ning, but by that time

the economic perils of the middle years of the war had been sufficiently

overcome to permit relative security, renewed and deepened popular

support or acceptance, and a tempered self-confidence.

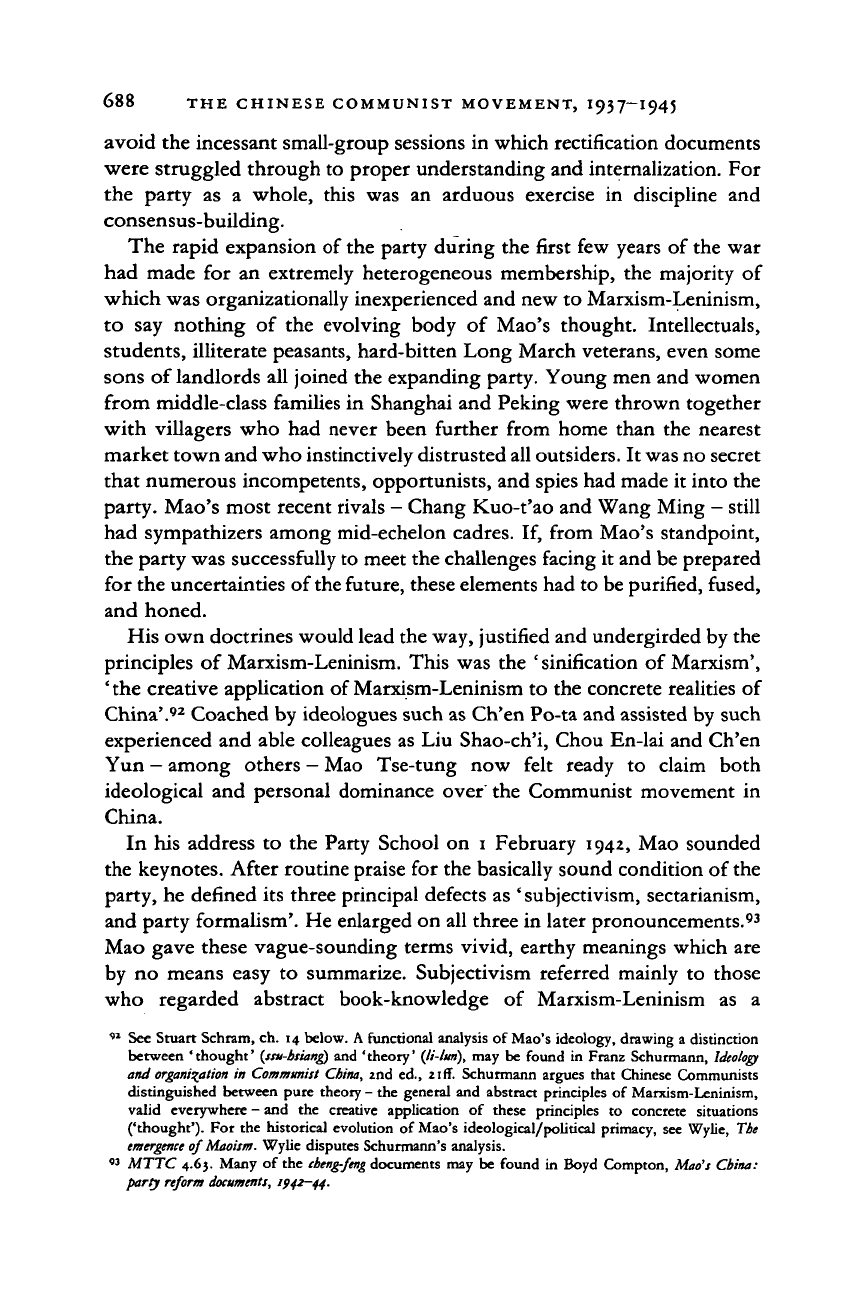

Rectification.

In the ideological and political realms, the most visible

effort was the ' rectification campaign'.

90

It formally began on

1

February

1942,

when more than one thousand party cadres assembled in Yenan to

hear Mao Tse-tung address the opening of the CCP's Party School. Cadre

education and concern for the party's ideological soundness had always

been an important concern.^as can be seen in the earlier writings of Mao,

Liu Shao-ch'i and others. But the decision to launch this particular

campaign was probably made at an 'enlarged session' of the Political

Bureau, held in September 1941, which called for 'development of a

party-wide ideological revolution' and elimination of 'factions which

formerly existed and played an unwholesome role in the history of our

party.'

91

Unfortunately, none of the documents of this very significant

meeting are presently available and little is known about it.

The campaign was never formally declared to be over, but by the second

half of 1944 its principal goals were apparently thought accomplished and

it no longer made a major claim upon the time and attention of party

members. Throughout, the rectification campaign was an intra-party

exercise, limited to party members, none of whom could ignore the

compelling force of Mao's addresses and statements delivered during the

spring and summer of 1942. In Shen-Kan-Ning, no party member could

88

Schran, 120.

M

Schran, 146. Textile production data are broken down into various sectors (percentages for 1943):

home industry (44%), state-owned enterprises (31%), capitalist enterprises (19%), Chinese

Industrial Cooperatives (6%).

90

'Rectification' is the customary translation

oicbeng-tun

tso-jeng.

Cheng-tun

means to set things aright

by a very thorough shaking up;

tso-feng

refers to all aspects of the way one does things, to one's

' work style'.

•' Wylie, 166.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

688

THE CHINESE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT, I937—1945

avoid the incessant small-group sessions

in

which rectification documents

were struggled through

to

proper understanding and internalization.

For

the party

as a

whole, this

was an

arduous exercise

in

discipline

and

consensus-building.

The rapid expansion

of

the party during

the

first

few

years

of

the

war

had made

for an

extremely heterogeneous membership,

the

majority

of

which was organizationally inexperienced and new

to

Marxism-Leninism,

to

say

nothing

of the

evolving body

of

Mao's thought. Intellectuals,

students, illiterate peasants, hard-bitten Long March veterans, even some

sons

of

landlords

all

joined the expanding party. Young men and women

from middle-class families

in

Shanghai and Peking were thrown together

with villagers

who had

never been further from home than

the

nearest

market town and who instinctively distrusted all outsiders.

It

was no secret

that numerous incompetents, opportunists, and spies had made

it

into

the

party. Mao's most recent rivals

-

Chang Kuo-t'ao

and

Wang Ming

-

still

had sympathizers among mid-echelon cadres.

If,

from Mao's standpoint,

the party was successfully to meet the challenges facing

it

and be prepared

for the uncertainties

of

the

future, these elements had to be purified, fused,

and honed.

His own doctrines would lead the way, justified and undergirded by the

principles

of

Marxism-Leninism. This

was the

' sinification

of

Marxism',

' the creative application

of

Marxism-Leninism

to the

concrete realities

of

China'.

92

Coached by ideologues such as Ch'en Po-ta and assisted

by

such

experienced

and

able colleagues

as Liu

Shao-ch'i, Chou En-lai

and

Ch'en

Yun

-

among others

-

Mao Tse-tung

now

felt ready

to

claim both

ideological

and

personal dominance over

the

Communist movement

in

China.

In

his

address

to the

Party School

on i

February 1942, Mao sounded

the keynotes. After routine praise

for

the basically sound condition

of

the

party,

he

defined

its

three principal defects

as '

subjectivism, sectarianism,

and party formalism'. He enlarged

on

all three

in

later pronouncements.

93

Mao gave these vague-sounding terms vivid, earthy meanings which

are

by

no

means easy

to

summarize. Subjectivism referred mainly

to

those

who regarded abstract book-knowledge

of

Marxism-Leninism

as a

92

See

Stuart Schram,

ch. 14

below.

A

functional analysis

of

Mao's ideology, drawing

a

distinction

between 'thought' (ssu-hsiang)

and

'theory' (li-lun),

may be

found

in

Franz Schurmann, Ideology

and organisation

in

Communist China,

2nd ed.,

2iff.

Schurmann argues that Chinese Communists

distinguished between pure theory

- the

general

and

abstract principles

of

Marxism-Leninism,

valid everywhere

- and the

creative application

of

these principles

to

concrete situations

('thought').

For the

historical evolution

of

Mao's ideological/political primacy,

see

Wylie,

Tie

emergence

of

Maoism. Wylie disputes Schurmann's analysis.

93

MTTC 4.63. Many

of

the cbeng-feng documents

may

be

found

in

Boyd Compton, Mao's China:

party reform documents, 1)42—44.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE MIDDLE YEARS I939-I943 689

talisman or panacea, but made no effort to apply its principles to actual

problems. These half-baked intellectuals were like chefs who studied

recipes but never cooked a dish, or those who 'merely take the arrow

in hand, twist it back and forth, and say again and again in praise,

"excellent arrow, excellent arrow" but are never willing to shoot it'.

Instead,

Our comrades must understand that we do not study Marxism-Leninism because

it is pleasing to the eye, or because it has some mystical value It is only

extremely useful We must tell them honesdy,' Your dogma is useless', or, to

use an impolite phrase, it is less useful than shit. Now, dogshit can fertilize a

field, and man's can feed a dog, but dogma? It can't fertilize a field or feed a

dog. What use is

it?

94

But if Mao's most scathing remarks were directed at dogmatic intellectuals

who acted like the mandarins of old, subjectivism also had an opposite

side:

empiricism. This was the tendency to view each situation exclusively

in its own terms and to rely only upon one's own experience, with no

ideological guidance. Empiricism was more likely to be encountered in

poorly educated peasant cadres whose horizons were narrow. In both

cases,

Mao called for the wedding of theory with practice.

Sectarianism was nearly as serious. Here Mao spoke of democratic-

centralism, charging the sectarians (naming only Chang Kuo-t'ao, already

read out of the party, but again implying Wang Ming) with forgetting

centralism - the ultimate authority of the Central Committee, now clearly

controlled by Mao and his followers. Sectarianism had seemingly prosaic

dimensions as well, affecting the relations between local cadres and

outsiders, between army and civilian cadres, between old and new cadres,

and between party members and those outside the party. Sometimes

individual units or localities put their interests ahead of the general good

by 'not sending cadres on request, sending inferior men as cadres,

exploiting one's neighbors and completely disregarding other organs,

localities, and men. This reveals a complete loss of the spirit of

communism.'

95

Although these problems sounded ordinary, they were

both serious and quite intractable. Their effects might be ameliorated, but

were never fully removed.

Mao then turned to the subject of ' party formalism', or

tang

pa-ku,

devoting an entire address to this subject.

96

Pa-ku

summoned up for Mao's

listeners memories of the rigidly structured 'eight-legged' essays which

had been the centrepiece of the old imperial civil service examination

** MTTC 8.75; Compton, 21—2. Such crudities have been expunged from Mao's

Selected

works.

*

5

Compton, 27.

96

'Oppose party formalism' (8 Feb. 1942). Contained in Compton, 33-53. The short extracts below

are drawn from this source (sometimes retranslated).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

690 THE CHINESE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT, I937-1945

system. Although

he

spoke of pa-ku most directly

in

terms

of

the way

in which many party members attempted to communicate with the masses

(in literature, propaganda, directives, etc.), he clearly meant this rubric

to cover all manifestations of dogmatic subjectivism and sectarianism:

'if

we oppose subjectivism and sectarianism but

do

not

at

the same time

eradicate party formalism, they still have a place to hide'. Once again using

the language

of

the

lao-pai-hsing,

the ordinary peasant, Mao described

-

perhaps with deliberate irony

-

eight ways

in

which pa-ku formalism

showed

itself.

It

was wordy, windy and disgusting, 'like the lazy old

woman's long, foul-smelling footbindings which should be thrown into

the privy

at

once'.

It

was pretentious, abstract, insipid, cliche-ridden;

worse, it made a false show of authority and aimed to intimidate the reader

or hearer.

It

contained many foreign terms and constructions which had

little meaning for the average person, but seemed very learned.

It

often

lapsed into irresponsibility and pessimism, to the detriment of the people,

the resistance,

and the

revolution.

No one, Mao

asserted, would

understand

or

listen to a party that spoke in pa-ku style, much less want

to follow

it or

join

it.

Writers, intellectuals, former students and educated cadres generally

were obviously the principal object of Mao's attack. They were, of course,

more numerous in the Shen-Kan-Ning base than anywhere else, and many

of them were becoming restive and dissatisfied. Just

a

few weeks after

Mao's speeches before the Party School and the issuance

of a

central

directive on cadre education,

a

number of prominent intellectuals loosed

a barrage in the pages of

Liberation

Daily.

91

Ting Ling, the famous woman

author, criticized the party's compromises

in

the area

of

sexual equality

and the gap between noble ideals and shabby performance more generally.

Others such

as

Ai Ch'ing and Hsiao Chun added their voices. Perhaps

the most biting critique was contained

in

an essay entitled 'Wild lilies',

by an obscure writer, Wang Shih-wei, who employed the satiric

tsa-wen

(informal essay) style made famous by Lu Hsun. Although none of these

critics questioned

the

legitimacy

of the

party

or the

necessity

for

revolution, they felt that art had an existence apart from politics and they

graphically portrayed the dark side of life in Yenan. By implication, they

were asserting

the

autonomy

of the

individual

and the

role

of the

intellectual as social critic, just as they had

—

with party blessing

—

before

the war in Kuomintang-controlled areas of China.

" Merle Goldman,

LJterary dissent in Communist

China,

2 iff. At this time the chief editor of

Liberation

Daily was Ch'in Pang-hsien (Po Ku), and one of his associates was Chang Wen-t'ien. Both had

belonged to Wang Ming's faction in the early 1930s, though they had later moved much closer

than he to the Maoist camp. Yet without their approval, the dissidents could not possibly have

had their writings published in

Liberation

Daily.

Ting Ling was the paper's cultural affairs editor.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008