The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13: Republican China 1912-1949, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE MIDDLE YEARS 1939-1943 691

What had been praiseworthy in Shanghai during the early 1930s,

however,

was

unacceptable in Yenan

a

decade

later.

These intellectuals must

have felt they were taking a risk, but they could hardly have anticipated

the severity of the party's response. All of them were severely criticized

and made to recant, though most were eventually rehabilitated. Wang

Shih-wei, less prominent and more corrosive than most, was repeatedly

attacked in mass meetings, discredited, jailed, and secretly executed in 1947.

If

his

February addresses and other party directives had failed properly

to educate the intellectuals, Mao was ready to go further. He took these

steps in May 1942, in the lengthy 'Talks at the Yenan Forum on art and

literature'. Here he laid down, in explicit detail, the role of intellectuals

under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party. This statement

remained authoritative throughout Mao's lifetime, and continues after his

death to exert its influence. In

brief,

' Talks' denies the independence and

autonomy of the mind, apart from social class. One can only speak or

write from a class standpoint; intellectuals are quite wrong to think that

there is some objectively neutral ground upon which they can stand. Since

this is so, art is one form of politics and the question then becomes

which

class it will represent. Revolutionary intellectuals must take their stand

with the proletariat for otherwise they serve the bourgeoisie or other

reactionary classes, even when they deny they are doing so. It follows that

the ultimate arbiter and guide for literature and art is the Chinese

Communist Party (led by Mao Tse-tung), since this is the vanguard, the

concentrated will, of the working classes.

Mao thus turned the tables on the intellectuals: no longer independent

critics, they were now the targets of criticism. So long as intellectuals were

willing to play the role of handmaidens to the revolution, as defined by

the CCP, they were needed and welcomed. There was no denying their

creativity and their skills, but these talents were to be valued only within

the limits set by the party. Socialist realism was to be the major mode

of literature and art, given naturalistic Chinese forms that would be at

once accessible to the masses and expressed in their own idiom, not that

of Shanghai salons. This meant that intellectuals had to go among the

peasants and workers, absorb their language and experience the harsh

realities of their lives. Altogether, Mao was calling for the transformation

of party intellectuals and of party members more generally.

By April

1942,

the Central Committee had published a list of twenty-two

documents to serve as the basis of cadre study and examination.

98

The

°

8

Sec Compton, 6-7. The list contained six items by Mao; five Central Committee documents

(probably authored in whole or in pan by

Mao);

one each by Liu Shao-ch'i, Ch'en Yun and K'ang

Sheng; a propaganda guide; an army report; three by Stalin; one by Lenin and Stalin; one by

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

692 THE CHINESE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT, I937—1945

means employed

to

inculcate their teachings included the now familiar

small-group study and struggle sessions, usually involving ' criticism and

self-criticism'. Straightforward instruction combined with peer pressure,

self-examination and coercive persuasion were designed

to

build

to

ever

higher levels

of

intensity until catharsis and commitment were achieved.

Mao likened

the

process

to the

curing

of a

disease: 'The first step

in

reasoning [sic]

is to

give the patient

a

good jolt: yell

at

him, "You're

sick!" so the patient will be frightened and break out all over in sweat;

then you can treat him effectively.' Yet the object is to '"cure the disease,

save the patient".. .The whole purpose is

to

save people, not cure them

to death.' 'Savage struggle' and 'merciless attack' should

be

unleashed

on the enemy, but not on one's comrades.

Mao's apotheosis did not, of

course,

occur suddenly in the midst of the

cheng-feng

campaign. His own instincts for power, his success

in

building

an influential and able coalition, and the proven effectiveness of his policies

were the main causes

of

his gradual rise

to

unchallenged pre-eminence

during the years after the Long March. As noted above (pages 663-4),

the parallel rise in stature of Chiang Kai-shek also played a role. With the

outbreak of the Pacific War

in

December 1941, Chiang instantly became

a leader of world renown and the symbol

of

China's resistance to Japan.

By late 1943, Chiang stood recognized at the Cairo Conference as one of

the

Big

Four,

and

publication

of

his famous

-

or notorious

-

China's

destiny

a

few months earlier was part

of

a bold effort

to

claim exclusive

leadership domestically.

Mao and the

CCP vigorously disputed this

claim." Put crudely,

if

there was

a

cult

of

Chiang, there had also

to be

a cult

of

Mao; an anonymous

'

Party Central' would not do.

Political and organisational

issues.

As we have already seen, political power

in Communist-controlled areas was exercised

at all

levels through

the

interlocking structures of party, government, army and mass organizations.

These structures were better developed

in

Shen-Kan-Ning than

in the

bases behind Japanese lines,

and

superimposed upon them

was the

apparatus

of

Party Central

and the

headquarters

of

the Eighth Route

Army. These organizations were much more comprehensive and effective

than those

of

imperial or Republican China. They were also democratic

Dimitrov (Comintern head);

and the

'Conclusion'

to the

History

of

the

CPSU.

Four

of

the

documents from the USSR were added later, as

if

by afterthought.

Mao and his supporters (especially Ch'en Po-ta) took this challenge very seriously, probably using

it

to

argue within the party that nothing should be done

to

hamstring Mao

or

compromise his

image. As late as 1945 (at the Seventh CCP Congress), Mao acknowledged that

'it

[the KMT]

still has considerable influence and power We must lower the influence and position

of

the

Kuomintang

in

the eyes

of

the masses and achieve the opposite with respect

to

ourselves.' See

Wylie, 218-25.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE MIDDLE YEARS I939—1943 693

in the specific sense that they enlisted

—

or required

—

broad participation

by many elements of the populace, but not in the sense that the governed

elected their ultimate leaders or determined policy. Yet the realities of

political control and popular support fell well short of the standards set

by the party itself and of the public image it tried to project. It was some

of these shortcomings that intellectuals such as Ting Ling and Wang

Shih-wei had dared to expose publicly, in a style unacceptable to the party.

In its confidential materials, however, party leaders at various levels

candidly acknowledged similar difficulties.

One problem was a growing bureaucracy and creeping routinization,

an almost inevitable consequence of such rapid expansion not only in

governing Shen-Kan-Ning

itself,

but also in directing an increasingly

far-flung war effort in the base areas far from Yenan. Many cadres were

' withdrawn from production', a burden that bore heavily on a population

facing economic distress in a backward region.

100

A second problem lay in the fact that political structures did not fully

penetrate the village (ts'un) level, but usually stopped at the next higher

township

(bsiang)

level, with jurisdiction over a variable number of

villages. Party Central was also concerned about the administrative

' distance' between county

(hsieri)

and township

(bsiang)

levels.

I01

Moreover,

coordination of activity at each level was hampered by the emphasis on

hierarchy. Despite the interlocking nature of the major organizational

structures, each had its own vertical chain of command to which it

primarily responded. Different units at the same level often had difficulty

working with one another. This tendency was most pronounced in the

party and the military, where 8RA cadres often looked down on their

civilian counterparts. Low morale was a problem, if a survey published

in April 1942 is typical: in the Central Finance Office

{Chung

tiai-fing),

61 per cent of party members surveyed reported themselves' discontented'

{pu-an-hsiti)

with their work assignment.

102

100

Only crude estimates are possible. Party membership is not directly useful, since many low-ranking

party members

did

engage

in

production.

In

late 1941, there were about

8,000

officials

who

received grain stipends (Selden,

1

j 1). This figure apparently does not include upper-echelon party

cadres

nor the

garrison forces

of

about 40,000, most

of

which,

up to

this time, were also

non-producers.

The

total, therefore,

may

have reached 50,000.

In a

population

of 1.4

million,

probably

no

more than one-third were males between

the

ages

of

15

and

45. Thus, perhaps

as

many

as

10%

of

the able-bodied male population

of

SKN was withdrawn from production.

101

Evasion

at the

village level

is

graphically portrayed

in an

officially celebrated short story,

'Li

Yu-ts'ai's clapper-talk',

by the

folk-writer Chao Shu-li. The unlikely hero,

an

impoverished and

illiterate farm labourer with a talent for satiric spoken rhymes (clapper-talk), uses pointed doggerel

to expose village big-wigs who for years had hoodwinked party cadres on their tours of inspection

from district headquarters.

102

Chieb-fangjib-pao

(3

April, 1941).

The

survey also revealed that 87%

had

joined

the

party after

the outbreak of the war; 39% were illiterate. This is the only such

'

public opinion survey' known

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

694

THE

CHINESE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT, I937-I945

Such difficulties were attacked

in

two closely related new policies which

bore

the

unmistakeable stamp

of

Mao

Tse-tung.

Both began

in

December

1941,

a few

months before

the

rectification campaign.

The

first, called

' crack troops

and

simple administration'

{ching-ping

chien-cheng),

aimed

to

cut back

the

civil

and

military bureaucracy.

The

second,

'

Hsia-bsiang'

(to

the villages),

was

designed

to

penetrate

the

villages more deeply,

in

part

by transferring downward many cadres removed from higher

levels.

These

policies combined

to

decentralize many political and economic tasks, thus

providing

a

better balance between vertical command structures

and

lateral coordination

at

each level.

In the

process, many civil

and

military

cadres were ordered back into production;

for

most, that meant

to

engage

in farming, land reclamation,

or

primitive industry. Especially marked

for

transfer

to

basic levels were young intellectuals, both

to be

toughened

by

the

harsh conditions

of

life among

the

peasants

(a

corrective

to

subjectivism, dogmatism

and

formalism),

and to

contribute their badly

needed skills

to the

conduct

of

village affairs.

These campaigns were actively pushed during the winters

of

1941,

1942

and 1943, when they could be timed

to

coincide with the slack agricultural

season. Army units were directed

to

produce as much

as

possible

of

their

own food

and

other supplies,

in a

modern form

of

the fun-fien (garrison

farm) system

of

medieval times.

The

model project

for

this

was at

Nan-ni-wan, about thirty miles south-east

of

Yenan, where

the

359th

Brigade

of

the 8RA was assigned full-time

for

several years

to

agricultural

and rudimentary industrial development.

By

1943,

the

brigade claimed

it was supplying about 80 per cent

of

its own needs. Even Mao Tse-tung,

an inveterate chain-smoker, cultivated

a

symbolic tobacco patch outside

his cave

in

Yenan.

Although hard evidence is unavailable, these policies undoubtedly

had

some effect, particularly

in

organization and mobilization. ' Yet the failure

to report accomplishments

in the

aggregate,

the

emphasis

on

exemplary

achievements such as the Nanniwan project, and the [repeated] promulga-

tion of the policy

of "

better troops and simpler administration "... suggest

also that

the

progress

may not

have been

so

significant.'

In

early

1943,

during

the

third round

of

'simpler administration',

a

senior leader

acknowledged that the number

of

full-time officials had grown from 7,900

in 1941 to

8,200.

103

Given

the

general tone

of

these reforms

in

Shen-Kan-Ning

and the

emphasis

on

'mass line'

and

'from

the

masses,

to the

masses',

it is

103

The quotation is from Schran,

193.

For personnel

data,

see Selden, 215-16. This

leader (Lin

Po-ch'ii,

chairman

of

the

SKN

government) stated that 22,500 persons, exclusive

of

the military, were

supported

at

public expense.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE MIDDLE YEARS I939-I943 695

surprising, that mass organizations as such seem to have played no

prominent role. Our only data on such organizations in SKN come from

1938,

when 30 per cent of the population (421,000 out of

1,400,000)

was

said to be enrolled in peasant associations; at the same time, about 25 per

cent of women and 32 per cent of men were members of women's

organizations and of

the

part-time militia, respectively.' One suspects that

these organizations for the most part lapsed into inactivity and that their

functions were taken over principally by government and party In

between.. .periods of intense activity [such as the 1942 rent-reduction

campaign] their membership and organization existed largely on paper.'

104

United front. Worsening relations with the Nationalists and the impact

of Japanese consolidation brought more attention to united front work,

not less. Beginning in mid-1940, CCP headquarters repeatedly issued

confidential directives stressing the importance of such work in approaches

to ' friendly armies', to all but the most pro-Japanese or anti-Communist

organizations, and to all classes and strata of society. United Front Work

Departments (UFWD) had been established in 1937 under the Central

Committee, and at lower levels as well. The importance accorded this work

is indicated by the fact that from late 1939 (when Wang Ming was

transferred) until 1945 or 1946, Chou En-lai's principal responsibilities

were as head of the central UFWD and the closely related Enemy

Occupied Areas Work Department. He repeatedly called for the further

extension and reinvigoration of UFWD at all levels, insisting upon its

importance and implying that it had fallen seriously into neglect under

his predecessor.

105

The united front, thus, was not simply a tactical device but part of a

general strategy of particular value in times of weakness or crisis. Each

concrete problem, from local affairs to national policies, could be analysed

as having three components: the party and its dedicated supporters, a large

intermediate stratum (or strata), and ' die-hard' enemies. The goal was to

isolate the 'die-hards' by gaining the support or neutrality of as many

intermediate elements as possible. Isolated enemies might then be dealt

with one by one. As early as October 1939, Mao had asserted that 'the

united front, armed struggle, and party-building are the three fundamental

questions for our party in the Chinese revolution. Having a correct grasp

of these three questions and their interrelations is tantamount to giving

correct leadership to the whole Chinese revolution.'

106

Applications of

this strategy, however, were tactical and extremely flexible, aimed at

•« Selden, 142-3.

103

See Van Slyke, Enemies ami friends, 116-21.

106

Mao, 'Introducing The

Communisf,

Mao, SW, 2.288.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

696 THE CHINESE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT, I937-I945

carefully defined groups

or

organizations. Precisely because the united

front served long-range revolutionary goals,

it

avoided ideological

formulae, seeking in each case to find and exploit those individuals, issues,

incentives or pressures that might further the party's cause:

In the past, the usual approach was toward making political contacts; very rarely

was serious work done to make friends, even to the point of remaining aloof

and uncooperative. Hereafter, we must

use

all possible social connections (family,

fellow townsmen, classmates, colleagues, etc.) and customs (sending presents,

celebrating festivals, sharing adversities, mutual aid, etc.), not only

to

form

political friendships with people, but also to become personal friends with them

so that they will be completely frank and open with

us.

107

In this spirit

the

CCP began

in the

spring

of

1940

to

publicize

the

'three-thirds system'

(san-san

chib).

According

to

this approach, popular

organs

of

political power

-

but not the party

or

the army

-

should

if

possible

be

composed

of

one-third Communists, one-third non-party

left-progressives, and one-third from 'the intermediate sections who are

neither left nor right'. As Mao explained,

The non-party progressives must

be

allocated one-third of the places because they

are linked with the broad masses of the petty-bourgeoisie. This will be of great

importance in winning over the latter. Our aim in allocating one-third of the

places to the intermediate sections is to win over the middle bourgeoisie and the

enlightened gentry At the present time, we must not fail to take the strength

of

these

elements into account and we must be circumspect in our relations with

them.

108

The policy thus aimed to make base area regimes more acceptable to the

upper levels of the rural population, but it represented no relinquishment

of Communist leadership. In practice, representation varied widely. Mao's

directive itself had noted that 'the above figures for the allocation of places

are not rigid quotas

to

be filled mechanically; they are

in

the nature of

a rough proportion, which each locality must apply according

to its

specific circumstances'.

In Shen-Kan-Ning, the proportion of party members in popular organs

after 1941 conformed fairly well

to the

one-third guideline

for

CCP

members.

In a

few cases, elected party members withdrew, with public

fanfare, from their assembly seats

in

order

to

conform more closely

to

the desired ratio. Border Region leaders felt that the policy was quite

helpful in allaying the fears and enlisting the support of the middle and

upper strata

of

the peasantry, who had been hardest

hit by

the steep

107

From

a

directive

of

the Central Committee United Front Work Department, 2 Nov. 1940. See

Van Slyke, Enemies and friends, 269.

108

'On the question of political power in the anti-Japanese base areas', Mao, SW, 2.418.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE MIDDLE YEARS 1939-1943 697

increases in taxes

—

even though poorer peasants had misgivings about

former landlords and evil gentry worming their way back into positions

of influence. This partly real, partly symbolic improvement of their

political fortunes, combined with their share of production increases,

kept these social strata well in line —particularly since they had few

alternatives.

Altogether, then, the economic, ideological and organizational/political

steps taken in Shen-Kan-Ning between 1940 and 1944 may not have fully

measured up to the public image the CCP sought to project, nor the

assessment sometimes made by outside observers. But they were impres-

sively effective nevertheless, particularly when contrasted with the

performance of the Nationalist regime during the same period.

New

policies

in

bases behind Japanese

lines

The North and Central China base areas behind Japanese lines faced

crises not only more severe but somewhat different from those in

Shen-Kan-Ning during the middle years of the war. For example, SKN

did not have to cope with military attacks, nor was it forced to move from

one area to another. SKN's administrative apparatus was much more fully

developed than those in the base areas, and prewar socio-economic change

had progressed much further. Because the CCP-controlled regions behind

Japanese lines were so varied and the data concerning them so fragmentary,

base-by-base treatment is impossible in the space available here. We are

thus constrained to describe events and policies in rather general terms,

illustrating them with examples from one or more bases. This will distort

complex realities by making them appear more uniform than they actually

were.

In the face of Japanese military pressure, all base area organs undertook

a wide range of active and passive defence

measures.

Villagers, grain stores,

animals and other possessions were evacuated to safer areas or went into

hiding. Valuables were buried. Military units dispersed after planting

primitive mines and booby traps, and merged with the peasantry, though

this was scant protection when the Japanese tried to kill all who fell into

their hands, or when they could be identified by collaborators or resentful

local elites anxious to settle scores.

Many bases, especially those on the North China plain, literally went

underground into what became an astonishing network of caves and

tunnels, often on two or more levels and linking up a number of villages.

Multiple hidden entrances, blind alleys, and subterranean ambush points

frustrated Japanese pursuers. When the Japanese countered by trying to

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

698 THE CHINESE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT, 1937-1945

flood the tunnels or by pumping poison-gas into them, the Chinese

responded with diversion channels and simple air locks.

Survival depended on the organized leadership of the party and the

army, and on the tenacity of the peasantry. But where bases had to

evacuate or reduce their operations to guerrilla status, the existence of

other bases where they might take haven was also essential. Those left

behind, whether cadres or ordinary peasants, were encouraged to take on

' white skins and red hearts', that is, to acquiesce when there was no other

choice. Despite the ingenuity and courage with which the Chinese

peasantry met these challenges, departure from a particular locale of most

of the party-led apparatus and main force military units sometimes

imposed too heavy a burden upon local self-defence forces. On occasions

when they collapsed, villages reverted to the control of local elites who

often took violent revenge. Meanwhile, in more secure settings, organized

activity continued, as the exiles waited to restore or reactivate the

infrastructures of their home districts. The network of bases across North

and Central China provided the Communist-led movement with a

resilience and capacity for recovery possessed by no other Chinese forces.

That the surviving core areas were able under these conditions to pursue

their political, social and economic objectives at all was remarkable. Yet

they did so quite actively, with varying degrees of

success.

Chin-Ch'a-Chi

and some parts of Chin-Chi-Lu-Yii undertook the most extensive and

effective reforms. The Central China bases, most of which came into

sustained operation about two years later, were less advanced. Shantung

lagged even further behind.

Economically, the shift from the first to the second phases of the war

was less abrupt in these bases than in SKN because they had always

operated under difficult conditions and without any outside subsidy. But

they too had for a time depended upon contributions - 'those with

strength give strength, those with money give money' - loans, and some

confiscations. The shift to 'rational burden' and ultimately to a unified

progressive tax system took place as political control and administrative

machinery became more effective. In Chin-Ch'a-Chi, the rational burden

system was adopted in 1939, and gave way to the unified progressive tax

plan in 1941. In fact, however, several systems were operating at the same

time,

depending on whether the region in question was a consolidated

core area, a recently established base, or

a

guerrilla zone. None of the other

bases behind Japanese lines were able to adopt the unified tax system.

While the land tax was the principal source of revenue, many of the older

surtaxes had to be continued as a supplement, especially in partly

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE MIDDLE YEARS I939—1943 699

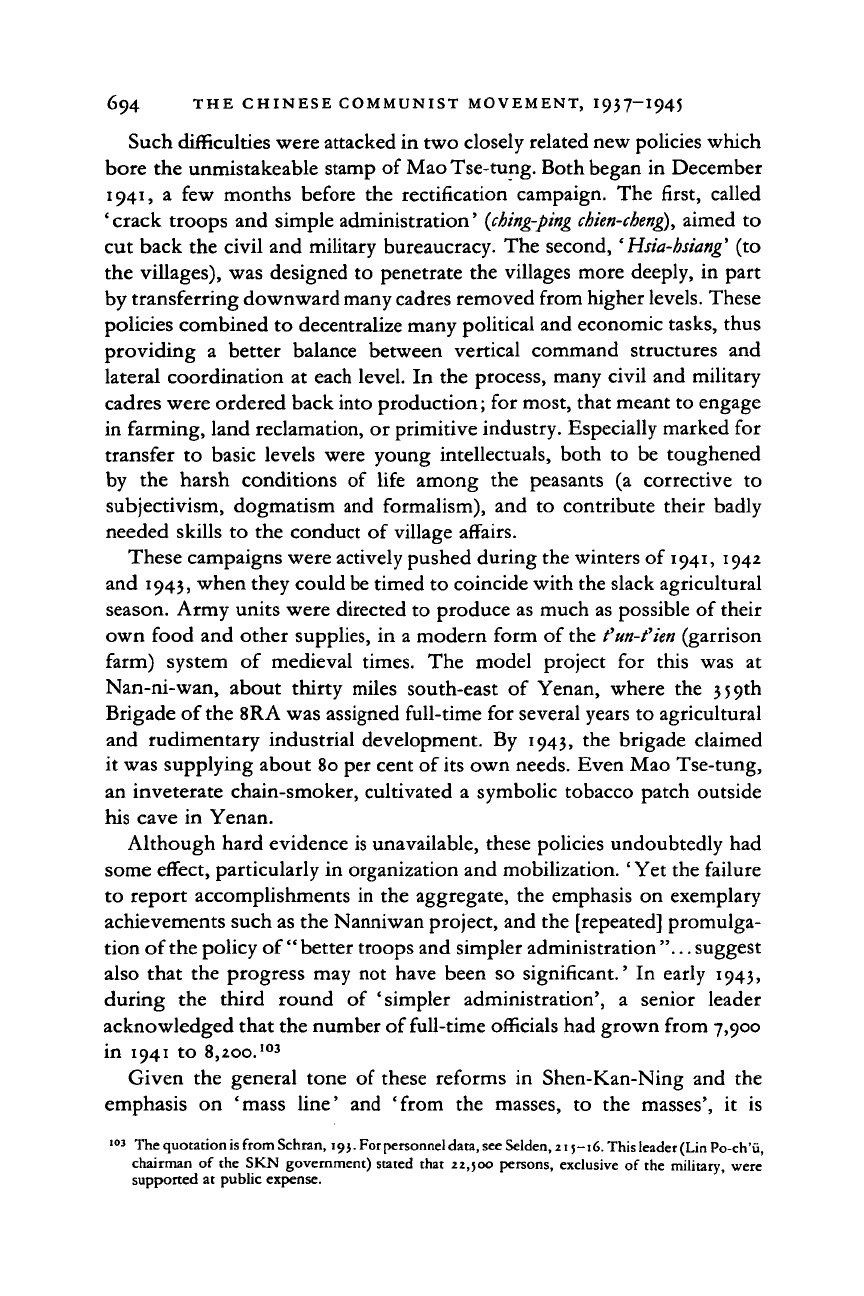

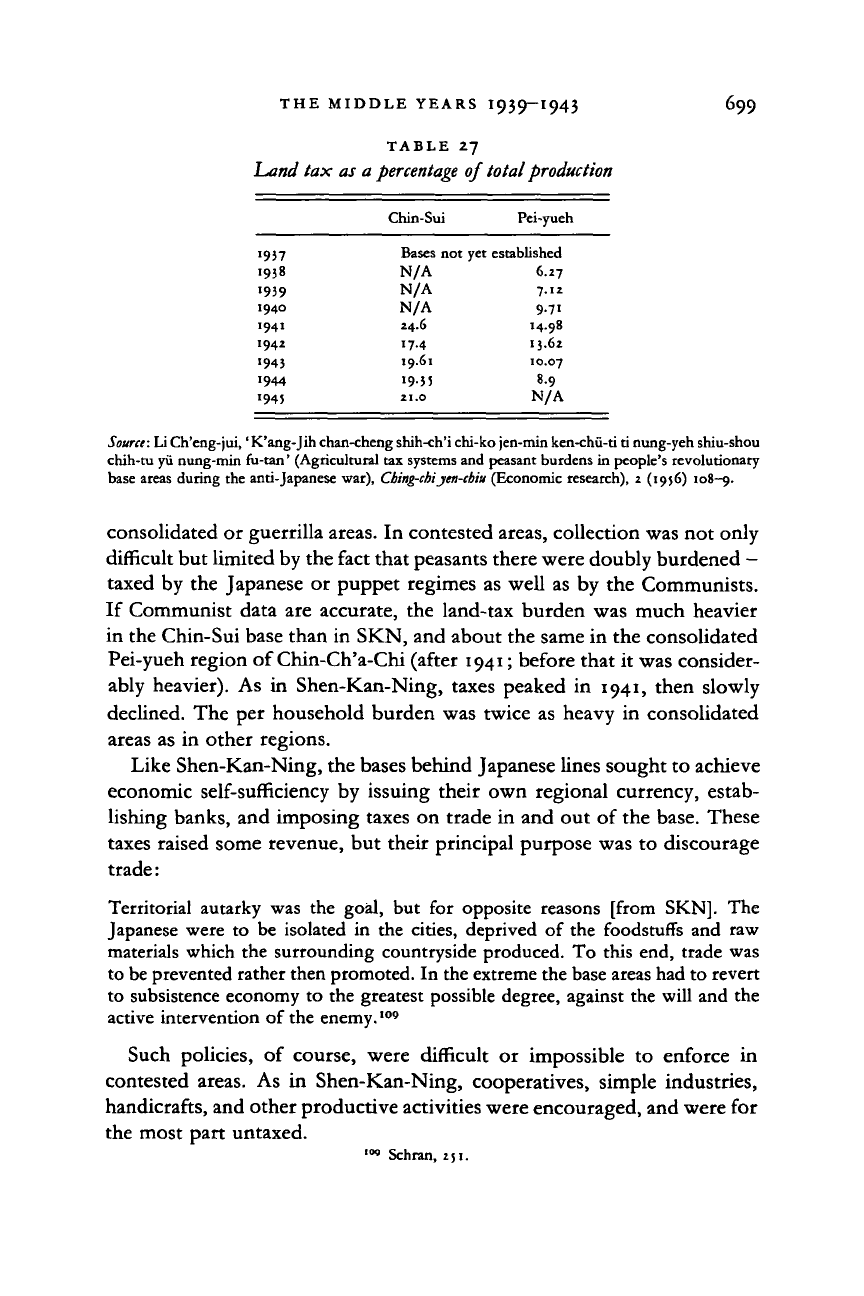

TABLE 27

Land tax as a

percentage

of total production

Chin-Sui Pei-yueh

1957 Bases

not yet

established

1938

N/A 6.27

1939

N/A 7.12

1940

N/A 9.71

1941

24.6 14-98

1942

17.4 13.62

1943

19.61 10.07

1944

19.35 8.9

1945

21.0 N/A

Source:

Li

Ch'eng-jui,'

K'ang-Jih

chan-cheng shih-ch'i chi-ko jen-min ken-chu-ti

ti

nung-yeh shiu-shou

chih-tu

yii

nung-min

fu-tan'

(Agricultural

tax

systems

and

peasant burdens

in

people's revolutionary

base areas during

the

anti-Japanese

war),

Cbing-cbiyen-cbiu (Economic

research),

2

(1956)

108-9.

consolidated or guerrilla areas. In contested areas, collection was not only

difficult but limited by the fact that peasants there were doubly burdened -

taxed by the Japanese or puppet regimes as well as by the Communists.

If Communist data are accurate, the land-tax burden was much heavier

in the Chin-Sui base than in SKN, and about the same in the consolidated

Pei-yueh region of Chin-Ch'a-Chi (after 1941; before that it was consider-

ably heavier). As in Shen-Kan-Ning, taxes peaked in 1941, then slowly

declined. The per household burden was twice as heavy in consolidated

areas as in other regions.

Like Shen-Kan-Ning, the bases behind Japanese lines sought to achieve

economic self-sufficiency by issuing their own regional currency, estab-

lishing banks, and imposing taxes on trade in and out of the base. These

taxes raised some revenue, but their principal purpose was to discourage

trade:

Territorial autarky was the goal, but for opposite reasons [from SKN]. The

Japanese were to be isolated in the cities, deprived of the foodstuffs and raw

materials which the surrounding countryside produced. To this end, trade was

to be prevented rather then promoted. In the extreme the base areas had to revert

to subsistence economy to the greatest possible degree, against the will and the

active intervention of the enemy.

109

Such policies, of course, were difficult or impossible to enforce in

contested areas. As in Shen-Kan-Ning, cooperatives, simple industries,

handicrafts, and other productive activities were encouraged, and were for

the most part untaxed.

'« Schran, 251.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

700 THE CHINESE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT, 1937-1945

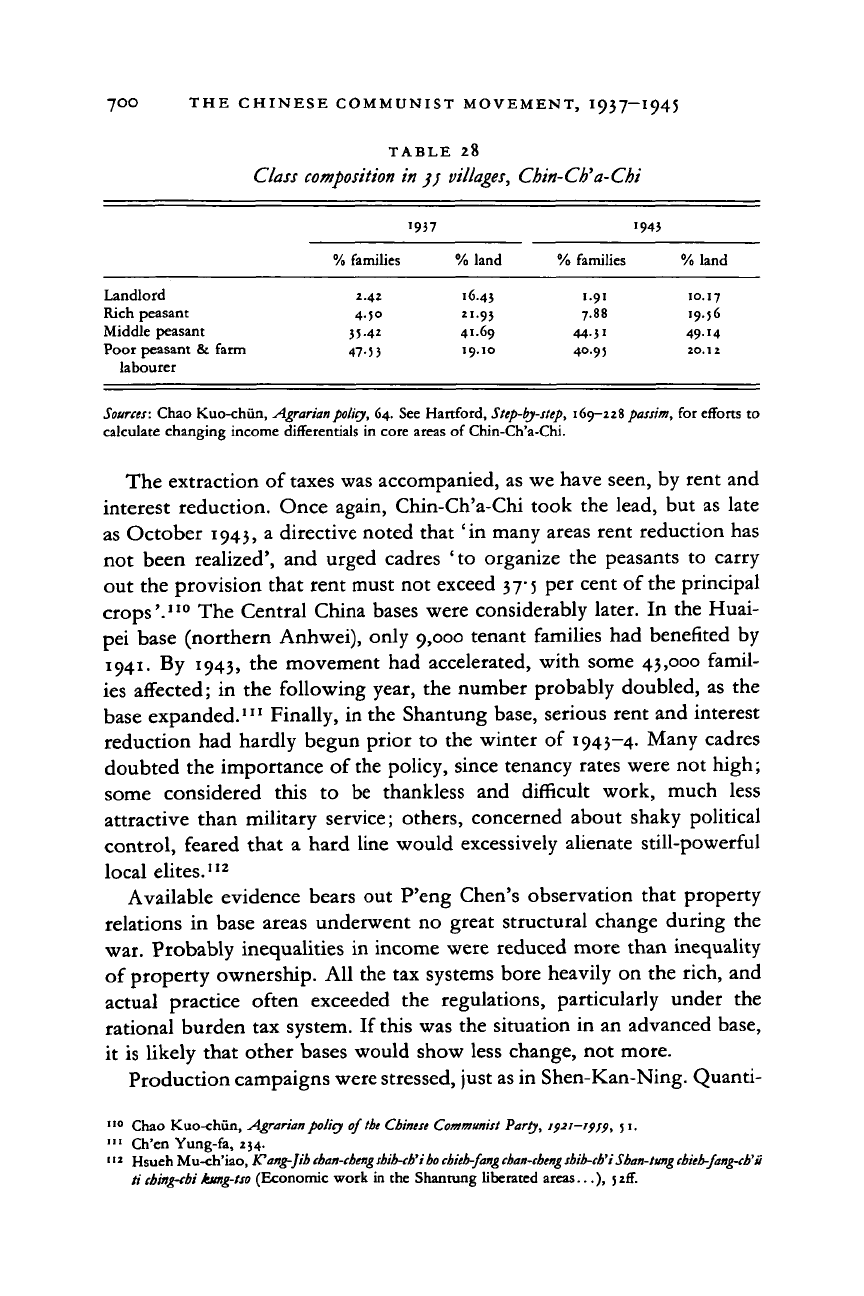

TABLE 28

Class

composition

in $)

villages,

Chin-Cb'a-Chi

1937

1943

% families % land

%

families % land

Landlord

2.42 16.43 '-9

1

10.17

Rich peasant

4.50 21.93 7"

")•)(>

Middle peasant 3542

41-69 4431

49-

• 4

Poor peasant & farm

47.j

j

19.10 40.9) 20.12

labourer

Sources:

Chao Kuo-chiin, Agrarian

policy,

64. See Hartford,

Step-by-step,

169-228

passim,

for efforts

to

calculate changing income differentials in core areas of Chin-Ch'a-Chi.

The extraction of taxes was accompanied, as we have seen, by rent and

interest reduction. Once again, Chin-Ch'a-Chi took the lead, but as late

as October 1943, a directive noted that 'in many areas rent reduction has

not been realized', and urged cadres

'to

organize the peasants

to

carry

out the provision that rent must not exceed 37-5 per cent of the principal

crops'.

110

The Central China bases were considerably later.

In

the Huai-

pei base (northern Anhwei), only 9,000 tenant families had benefited by

1941.

By 1943, the movement had accelerated, with some 43,000 famil-

ies affected;

in

the following year, the number probably doubled, as the

base expanded.

111

Finally, in the Shantung base, serious rent and interest

reduction had hardly begun prior to the winter

of

1943-4. Many cadres

doubted the importance of the policy, since tenancy rates were not high;

some considered this

to be

thankless

and

difficult work, much less

attractive than military service; others, concerned about shaky political

control, feared that

a

hard line would excessively alienate still-powerful

local elites.

112

Available evidence bears out P'eng Chen's observation that property

relations

in

base areas underwent no great structural change during the

war. Probably inequalities in income were reduced more than inequality

of property ownership. All the tax systems bore heavily on the rich, and

actual practice often exceeded

the

regulations, particularly under

the

rational burden tax system. If this was the situation in an advanced base,

it is likely that other bases would show less change, not more.

Production campaigns were stressed, just as in Shen-Kan-Ning. Quanti-

1

Io

Chao Kuo-chun, Agrarian

policy

of

the Chinese Communist

Party,

ipif-ifjp, ;

i.

111

Ch'en Yung-fa, 234.

112

Hsueh

Mu-ch'iao,

Kong-Jib cban-cbeng sbib-cb'i bo cbitb-fang cban-cbeng sbib-cb'i Sban-tung cbieb-fang-cb'S

ti

cbing-cbi ksmg-tso

(Economic work in the Shantung liberated areas...),

5

2C

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008