The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13: Republican China 1912-1949, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE LAST YEARS OF THE WAR I944-1945 721

cooperate with Chiang Kai-shek. Otherwise,

the

Chinese nation would

perish.'

134

PROSPECTS

The surrender

of

Japan

was, of

course,

an

event

of

great

and

joyful

significance across China's war-torn land.

It

symbolized

the end of the

foreign aggression,

and the

hope

of

all Chinese that genuine peace might

at last

be

achieved after seemingly endless pain

and

death.

But

Japanese

surrender did

not

mean that the war was over in China, since the Japanese

invasion was only one part

of

a

complex, many-sided political and military

conflict,

all

other aspects

of

which continued much

as

before. Even with

the Japanese, shooting continued

as

Japanese troops responded

to

orders

from

the

Nationalists

to

hold their positions

and

refuse surrender

to

Communist forces.

Thus Mao and his colleagues hardly had time

to

pause and congratulate

themselves

on the

progress they

had

made since 1937.

In 'The

situation

and

our

policy after

the

victory

in the war of

resistance against Japan'

(13 August 1945), however,

Mao

took time

to

look both backward

and

forward.

The

past

was

portrayed

in

black

and

white;

no

shades

of

grey

entered

the

description

of the

Kuomintang

and its

leaders, either prior

to

or

during

the

Sino-Japanese War. According

to

Mao,

the

risk

of

civil

war

was

very great, because Chiang Kai-shek

and his

foreign backers

would

try to

seize

a

victory that rightly belonged

to the

people. Mao

was

hard-headed enough

to see

that

the

balance

of

power

in

China

did not

yet favour

the

CCP: ' That

the

fruits

of

victory should

go to the

people

is

one

thing,

but

who will eventually

get

them.. .is another. Don't

be too

sure that

the

fruits

of

victory will fall into

the

hands

of

the people.' Some

of these fruits

—

all the

major cities

and the

eastern seaboard

—

would

surely

go to the

KMT, others would

be

contested,

and

still others

- the

base areas

and

some Japanese-occupied countryside

-

would

go to '

the

people'.

The

only question

was on

what scale

the

struggle would

be

fought: 'Will

an

open

and

total civil war break out?... Given

the

general

trend

of the

international

and

internal situation

and the

feelings

of the

people,

is it

possible, through

our

own struggles

to

localize

the

civil

war

or delay

the

outbreak

of a

country-wide civil war? There

is

this

possibility.'

It was in

this spirit that

Mao

Tse-tung, Chou En-lai,

and

General Patrick Hurley flew from Yenan

to

Chungking

on 28

August

to

discuss with Chiang Kai-shek the problems of peace, democracy and unity.

Finally,

Mao

Tse-tung stressed self-reliance.

He

identified

the

United

States

as a

hostile imperialist power

and

insisted that

no

direct help from

134

Stuart Schram, Chairman Mao talks

to

the people, 191.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

722 THE CHINESE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT, I937—1945

the Soviet Union was needed: 'We are not alone...[in the world, but]

we stress regeneration through our own efforts. Relying on the forces we

ourselves organize, we can defeat all Chinese and foreign reactionaries.'

Yet at the same time, 'Bells don't ring till you strike them...Only where

the broom reaches can political influence produce its full effect. .. .China

has a vast territory, and it is up to us to sweep it clean inch by inch...

We Marxists are revolutionary realists and never indulge in idle dreams.'

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER

13

THE KMT-CCP CONFLICT 1945-1949

NEGOTIATIONS AND AMERICAN INVOLVEMENT

By 1944 the American government had become increasingly anxious

to

quell the dissension that was undermining the anti-Japanese war effort

in China, and forestall a possible civil war that might involve the Soviet

Union

on

the side

of

the CCP once the Japanese surrendered. The

negotiations between the KMT and CCP, broken off after the New Fourth

Army incident in

1941,

had been resumed by 1943. The Americans became

actively involved with the arrival

in

China

of

Major General Patrick

J. Hurley, President Roosevelt's personal representative to Chiang Kai-

shek, in September 1944. Appointed US Ambassador a few months later,

Hurley's mission was, among other things,' to unify all the military forces

in China for the purpose of defeating Japan'.

The Hurley mission: 1944-194j

Optimistic interludes to the contrary notwithstanding, the first year of

Hurley's efforts to promote reconciliation between the leaders of China's

'two great military establishments' bore little fruit. The Communist

position announced by Mao at the Seventh Party Congress in April 1945

called for an end

to

KMT one-party rule and the inauguration

of a

coalition government in which the CCP would share power. This proposal

gained the enthusiastic support

of

the nascent peace movement

in

the

KMT areas, where fears of renewed civil conflict were mounting as the

fortunes of the Japanese aggressor declined. But

it

was not the sort of

proposal that the KMT government was inclined to favour. Then on the

day Japan surrendered, 14 August, Chiang Kai-shek invited Mao

to

journey to Chungking to discuss the outstanding issues between them.

Mao eventually accepted, and Ambassador Hurley personally escorted him

to

the

government's wartime capital from

his

own

at

Yenan.

The

ambassador continued

to

play his mediator's role

in

the subsequent

negotiations.

7

2

3

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

724

THE

KMT-CCP CONFLICT I945-I949

Mao returned

to

Yenan

on n

October. General principles had been

agreed upon, but the details of implementation had yet to be devised. Chou

En-lai remained

in

Chungking

to

work toward that end. The general

principles announced

in

their 10 October agreement,

at

the close

of

the

talks between Chiang and Mao, included democratization, unification of

military forces, and the recognition that the CCP and all political parties

were equal before the law. The government agreed further

to

guarantee

the freedoms of person, religion, speech, publication and assembly ;• agreed

to release political prisoners; and agreed that only the police and law courts

should

be

permitted

to

make arrests, conduct trials,

and

impose

punishments.

According to the agreement,

a

political consultative conference repre-

senting all parties was to be convened

to

consider the reorganization of

the government and approve a new constitution. The Communists agreed

to

a

gradual reduction

of

their troop strength

by

divisions

to

match

a

proportional reduction of

the

government's armed forces. The Communists

also agreed

to

withdraw from eight

of

their southernmost and weakest

base areas.' The government had bowed

to

the Communist demand

for

an end

to

one-party KMT rule; the Communists had abandoned their

demand

for

the immediate formation

of a

coalition government.

In so

doing, both sides were acknowledging the widespread desire

for

peace

on the part of a war-weary

public,

and the political advantages to be gained

from apparent deference to

it.

A key issue on which not even superficial agreement could be reached,

however, was that

of

the legality

of

the remaining ten Communist base

areas and their governments. Chiang Kai-shek demanded that they

be

unified under the administrative authority of the central government; the

Communists not surprisingly demurred. Even more crucial: while their

leaders were thus engaged

in

talking

peace,

the Communist and government

armies were engaged in a competitive race to take over Japanese-occupied

territory north

of the

Yangtze. That territory included

the

strategic

North-east provinces (Manchuria, as they were then known), where the

Communists were rushing to create

a

new base area.

General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander

of the

Allied

Powers (SCAP),

in his

General Order Number One, authorized

the

Chinese government

to

accept the Japanese surrender

in

China proper,

the island

of

Taiwan, and northern Indo-China. The forces of the Soviet

Union were

to

do the same in Manchuria. But the government, from its

wartime retreat in the south-west, was

at a

clear disadvantage

in

taking

1

China white

paper. 2.577-81; Mao Tse-tung, 'On the Chungking negotiations',

Selected

works,

hereafter Mao, SW, 4.53-63.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

a\

*-i

V>

3

00

3

<

C

~5

v-

C

o

D

Vi

'H

3

E

E

o

u

c

M

(fl

-O

3

(A

hi

u

-o

c

3

so

U

c

o

N

fi.

<

2

3

III

i

8

H

|1

-8

If

.

5

I

JI

^1

o-

o

O

UJ

Z

(A

*

<

.

±5

^1

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

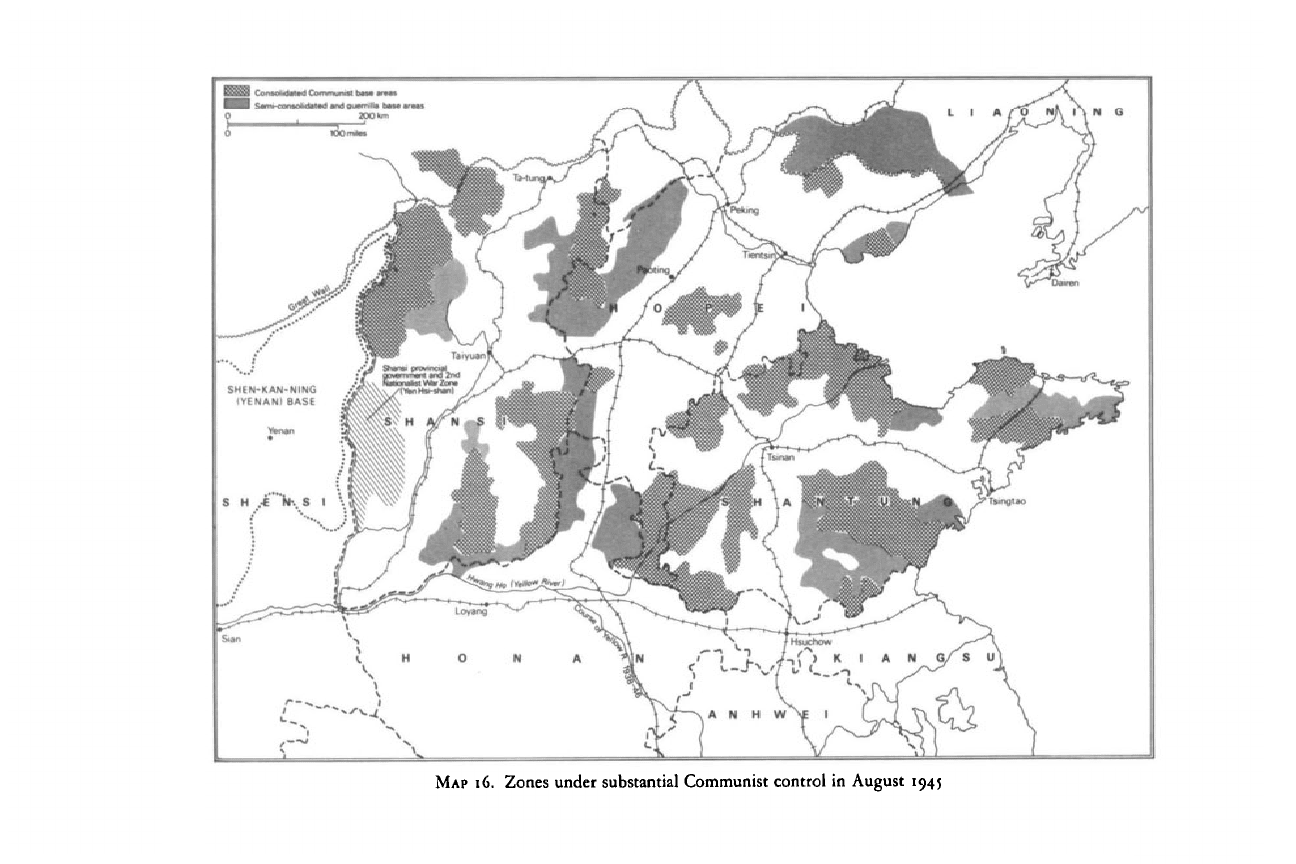

7*6 THE KMT-CCP CONFLICT I945-I949

over from

the

Japanese north

of

the Yangtze, since

the

Communists

already controlled much of the North China countryside.

Anticipating Japan's surrender, Chiang Kai-shek had ordered Com-

munist forces

on 11

August 1945

to

maintain their positions.

But in

accordance with conflicting orders from Yenan, Communist troops

launched

an

offensive

on

all fronts against Japanese-held keypoints and

communications lines to compel their surrender. Mao and the commander

of

the

Communist armies,

Chu

Teh, cabled

a

rejection

of

Chiang's

11 August order five days later.

On

23

August, therefore,

the

commander-in-chief

of

government

forces, General Ho Ying-ch'in, ordered General Okamura Yasuji, com-

mander of Japanese forces in China, to defend Japanese positions against

Communist troops if necessary, pending the arrival of government troops.

The Japanese were also ordered

to

recover territory recently lost

or

surrendered

to

Communist forces, and offensive operations were under-

taken following this order. From late August

to

the end

of

September,

more than 100 clashes were reported between Communist forces on the

one hand, and those of the Japanese and their collaborators on the other,

acting

as

surrogate

for the

KMT government.

As a

result

of

these

operations, the Communists lost some twenty cities and towns in Anhwei,

Honan, Hopei, Kiangsu, Shansi, Shantung and Suiyuan.

2

Among their

gains

was

Kalgan (Changchiak'ou), then

a

medium-sized city with

a

population

of

150,000—200,000, and capital

of

Chahar province. Taken

from the Japanese during the final week

of

August 1945, Kalgan was

a

key trade and communications centre for goods and traffic moving north

and south of the Great Wall. Because of its size and strategic location not

far from Peiping, Kalgan became something

of a

model

in

urban

administration

for

the Communists and

a

second capital

for

them until

it was captured by government forces one year later.

The United States also intervened on the government's

behalf,

trans-

porting approximately half

a

million

of

its troops into North China,

Taiwan and Manchuria. A force

of

53,000 US marines occupied Peiping,

Tientsin and other points in the north pending the arrival of government

troops. The US War Department order authorizing such assistance had

instructed that the principle of non-involvement in the KMT-CCP conflict

not be infringed. Yet the order contained an implicit contradiction, since

the two parties

to

the conflict viewed their race

to

take over from the

Japanese as part

of

their mutual rivalry. The US thus compromised the

principle

of

'non-involvement' from the start

in a

manner that would

2

Hsia-hua jib-pao

(New

China daily news), Chungking,

17 and 20

Sept.,

5, 6 and 22 Oct. 1945

(translated

in

Chinese Press Review, hereafter

CPR,

same dates except Oct.

23

for the last cited).

Also Foreign relations of

the

United States, hereafter FRUS, 194}, 7.567-68.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

NEGOTIATIONS AND AMERICAN INVOLVEMENT 727

characterize

the

American role

in

China throughout

the

period.

The

Chinese Communists began

at

once

to

protest

the

American garrison

duties

and

troop movements

as US

interference

in

China's domestic

affairs.

3

The presence

of

the Russians further complicated

the

clash

of

interests

in China

at

the end

of

the Second World War.

The

Soviet Union entered

the

war

against Japan

on 9

August 1945,

in

accordance with

the

Yalta

Agreements

of

11

February 1945. Soviet troops

had

just begun entering

Manchuria when

the

Japanese surrendered

on 14

August,

the

same

day

that

the

Soviet

and

Chinese governments announced

the

conclusion

of

a

treaty

of

friendship and alliance between their two countries. During

the

negotiations, Stalin had conveyed assurances to the Chinese representative,

T.

V.

Soong, that Soviet forces would complete their withdrawal from

the North-east within three months after

a

Japanese surrender.

4

The

deadline

for

Soviet withdrawal was thus

set for

15 November 1945.

The Chinese Communists were in

a

position to take maximum advantage

of those three months during which

the

Russians occupied the cities

and

major lines

of

communications

in the

North-east,

and no one

controlled

the countryside. During this time, while government forces were

leap-frogging over

and

around them

in

American transport planes

and

ships,

elements

of

the Communist Eighth Route and New Fourth Armies

were entering Manchuria

by

junk from Shantung

and

overland

on

foot

from several northern provinces. They were joined

by a

small force

of

North-eastern troops

led by

Chang Hsueh-szu,

a son of

the Manchurian

warlord Chang Tso-lin, which had been cooperating with the Communists'

guerrilla activities against the Japanese

in

North China. Another son,

the

popular Young Marshal, Chang Hsueh-liang, remained

a

hostage

to the

KMT-CCP united front under house arrest

in

KMT territory

for

his role

in

the

1936 Sian incident.

There is little evidence of direct Soviet military assistance to the Chinese

Communists at this time. But large quantities of arms and equipment from

the 700,000 surrendering Japanese troops

in

the North-east

did

find their

way either directly

or

indirectly into Chinese Communist hands.

5

The

Soviets also adopted delaying tactics

at a

number

of

points

to

prevent

the

Americans from landing Government troops

at

North-east ports. Finally,

Chou Pao-chung

and

remnants

of his old

Communist North-east

anti-Japanese allied army, which

had

fled across

the

border into

the

Soviet Union, returned with Soviet forces

in

1945. Other remnants

of

this army, which the Japanese had effectively destroyed

by

1940, emerged

3

FRUS,

rw,

7.576,

577. 4

MM.

611.

5

China

white paper, 1.381. Most

of

the arms and equipment

of

the

1.2

million Japanese troops that

surrendered elsewhere

in

China went

to

the government armies.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

728 THE KMT-CCP CONFLICT I945-I949

from prison and from underground

at

this time and began reorganizing

at once

in

cooperation with the Communist forces arriving from North

China.

By early November,

the

KMT government was aware that Soviet

withdrawal

on

schedule would mean immediate occupation

of

much of

the North-east by the Chinese Communists. Despite American assistance,

the government

had

already lost

the

race

to

organize

a

military

and

civilian takeover operation

for

Manchuria.

The

Chinese government

therefore negotiated with the Soviets who formally agreed both to extend

their stay and

to

allow government troops

to

enter the region

by the

conventional routes. New dates were set for Soviet withdrawal, first early

December and then early January. The date was extended twice more,

by which time the Soviets had more than overstayed their welcome. They

did not actually complete their evacuation from Manchuria until early May

1946.

Meanwhile, on 15 November, with some of

his

best troops transported

from

the

south and deployed along

the

Great Wall, Chiang Kai-shek

attacked Shanhaikuan, the gateway

to

Manchuria at the point where the

Wall meets the sea. He then proceeded to fight his way into the North-east

to take

by

force

a

region which had been controlled

for

fourteen years

by the Japanese and before that by the family of the Old Marshal, Chang

Tso-lin,

but

never

by

the KMT government. The still feeble Chinese

Communist forces

in the

region were

as yet no

match

for

Chiang's

American-equipped units. His strategy to take over the North-east, aided

by

the

Americans and

no

longer obstructed

by

the Soviets, thereafter

proceeded apace.

The Soviets took advantage of their delayed departure to augment their

war booty, dismantling and removing with their departing forces tons

of Manchuria's most modern Japanese industrial equipment.

6

With the

action shifting increasingly to the battlefield, the continuing negotiations

between the antagonists appeared pointless and Chou En-lai returned

to

Yenan

in

late November. Yet these economic and political costs paled

beside the strategic military error, later admitted by Chiang

himself,

of

transporting his best American-equipped troops directly to the North-east

from their deployment area in Yunnan and Burma without first consoli-

dating control

of

the territory in between. Whether these troops would

have been more successful in the battle for North China than they were

in the North-east must remain for ever an unanswered question. But some

of Chiang Kai-shek's best divisions entered

the

North-east never

to

re-emerge. His decision

to

commit them

to

the takeover

of

that region

was

a

blunder that would come to haunt the generalissimo, for

it

was

in

6

Ibid.

2.596-604.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

NEGOTIATIONS AND AMERICAN INVOLVEMENT 729

the North-east, with the failure of these troops to defeat the Communist

forces there, that his cause was finally lost.

7

Meanwhile, several more acts had yet to be played out on the diplomatic

stage. Also in late November 1945 Hurley resigned as ambassador to

China, damning certain American foreign service officers as he went for

allegedly undermining his mediation effort by siding with the CCP. These

charges would fester for years before culminating in the anti-Communist

allegations of the McCarthy era.

8

But in December 1945, President

Truman immediately appointed General George Marshall as his special

envoy to take up the mediator's task cast aside by Hurley. The president

instructed Marshall to work for a ceasefire between Communist and

government forces, and for the peaceful unification of China through the

convocation of a national representative conference as agreed upon by

Mao and Chiang during their Chungking negotiations.

The Marshall mission: 1946

Marshall arrived in China on 23 December 1945. The US was just then

completing delivery of equipment for 39 divisions of the government's

armed forces and eight and a third wings for its air force, fulfilling

agreements made before the Japanese surrender. Despite the obvious

implications of the American supply operation completed within the

context of the developing civil war in China, Marshall's peace mission

produced immediate results.

Agreement was quickly reached on the convocation of a Political

Consultative Conference (PCC) and a committee was formed to discuss

a ceasefire. This was the 'Committee of Three', comprising General

Marshall as chairman, General Chang Chun representing the government

and Chou En-lai representing the CCP. A ceasefire agreement was

announced on 10 January 1946, the day prior to the opening of the PCC.

The agreement called for a general truce to go into effect from 13 January,

and a halt to all troop movements in North China. The right of

government forces to take over Manchuria and the former Japanese-

occupied areas south of the Yangtze River was acknowledged by the

' Chiang Kai-shek, Soviet Russia in China: a

summing-up

at

seventy,

232—3. Li Tsung-jen later claimed

that his advice against this troop deployment went unheeded (Tbe memoirs of U Tsung-jen, 4} 5).

8

Hurley's first charges against the Foreign Service officers were made in his letter of resignation,

reprinted in China white paper, 2.581-4; also, FRUS, 194), 7.722-44. Among the many accounts

now available of this inglorious episode are: O. Edmund Clubb, The witness and I; John Paton

Davies, Jr. Dragon by the

tail;

Joseph W. Esherick, ed. host

chance

in China; E. J. Kahn, Jr. The

China bands; Gary May, China scapegoat; John S. Service, The Amerasia papers; Ross Y. Koen,

The China lobby in American politics; and Stanley D. Bachrack, The Committee of

One

Million: 'China

Lobby' politics, '9t)-i97i. See also Kenneth W. Rea and John C. Brewer, eds. The forgotten

ambassador: the reports of John Leighton Stuart,

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

73°

THE KMT-CCP CONFLICT

I945-I949

ceasefire agreement. An executive headquarters was set up in Peiping to

supervise the ceasefire and began functioning at once. It was led by three

commissioners representing the government, the CCP and the United

States.

Its truce teams were to be made up of equal numbers of

government and

CCP

personnel, with the American role confined to that

of assistance only.

The PCC

met from n to 31 January 1946 for the declared purpose of

seeking a peaceful solution to the

KMT-CCP

conflict.

Great

hopes were

placed in this conference, if not by the two main antagonists, then at least

by

all other concerned parties. For a time it was the chief focus of popular

attention and even after the hopes were shown to be illusory, the authority

of the PCC agreements was invoked by the government to legitimize a

number of its subsequent political actions.

The

PCC participants, although not democratically elected, were

acknowledged

by all to be representative of the major and minor political

groupings within the Chinese political arena. The participants comprised

38

delegates: eight from the KMT, seven from the

CCP,

five from the

Youth

Party,

two from the Democratic

League,

two from the Democratic-

Socialist

Party,

two from the National Salvation Association, one from

the Vocational Education Association, one from the

Rural

Reconstruction

Association, one from the

Third

Party,

and

nine

non-partisans.

Agreement

was reached on virtually all political and military

issues

outstanding between the KMT and the

CCP.

The agreements concerned:

the reorganization of the national government; a political programme to

end the period of

KMT

tutelage and establish constitutional government;

revision of the 1936 Draft Constitution; membership of the proposed

National

Constitutional Assembly which would adopt the revised

constitution; and reorganization of government and CCP armies under

a unified command.

The

PCC provided that a three-man military committee be formed to

devise plans for implementing conference resolutions calling for general

troop reductions and the integration of

CCP

forces into a unified national

army.

This group, the Military Sub-committee, was made up of General

Chang

Chih-chung for the government and

Chou

En-lai for the

CCP,

with

Marshall

serving as adviser.

They

announced agreement on 25 February,

with plans for a massive troop reduction on both sides. This was to be

accomplished within 18 months, at the end of which there would be

roughly

840,000 government troops in 50 divisions, and

140,000

troops

in 10 divisions on the Communist side, which would be integrated into

the national army. Agreement was

also

reached on the disposition of

these

forces with the majority of the Communist divisions to be deployed in

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008