The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 4: Early Modern Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE POWER STRUCTURE 95

tween daimyo or between retainers. There were differences in family

status and kokudaka size among daimyo and among retainers, but

before their respective lords, whether the shogun or the daimyo, they

were equal, and the free development of superior-inferior relation-

ships among them was suppressed. The lord-vassal relationships be-

tween the shogun and the daimyo and between the daimyo and the

retainers were public, and any other conditions of subordination were

deemed private and were forbidden.

Finally,

kogi

authority had a group character: The warrior of early

modern times was recognized as being of the warrior class only when

he was a member of the

kogi

group. Individual warriors did not pos-

sess their own land and live on it independently; their income from a

fief or stipend, under conditions created by Hideyoshi and continued

by the Tokugawa, was guaranteed by their belonging to the kogi

group. The strict separation of the warrior and peasant estate was a

precondition for this. Conversely, a warrior was a warrior by virtue of

his conducting public service as a member of the

kogi;

this was also the

source of the logic by which the warriors were able to collect taxes

(nengu)

and monopolize government. If a warrior were given to willful-

ness,

he would be punished as one who had departed from the group's

rationale. The unification of Japan in the sixteenth century had given

risen to such a public authority.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER

3

THE SOCIAL

AND

ECONOMIC

CONSEQUENCES

OF

UNIFICATION

INTRODUCTION

Japan underwent

a

major transformation

in its

social organization

and

economic capacity during the latter half of the sixteenth

century.

These

changes were

of

such enormous historical significance that historians

see them as marking Japan's transition from

its

medieval

(chusei)

to

its

early modern

(kinsei)

age.

The

first

currents of this transmutation radi-

ated throughout Japan during

the

late fifteenth

and

early sixteenth

centuries, and the impulses manifested themselves in the appearance of

self-administering towns such as Sakai and relatively autonomous,

self-

governing rural communities, commonly referred

to as

soson.

These

communities were

the

ultimate products

of

social movements that ear-

lier

had

begun

to

shake

the

foundations

of

the medieval,

shoen-based

political and economic order. Central to this process

was

the appearance

of organized peasant protest, increasingly common

in the

Kinai region

and its environs in the late medieval period, and the emergence through-

out large portions

of

Japan

of

local associations,

or

ikki, that were

formed

for

military purposes

and

reasons

of

self-defense. Examples of

such leagues include

the

so-called

tsuchi

ikki, peasant organizations

formed

to

resist economic demands made

by

proprietory lords, a phe-

nomenon especially common

in the

Kyoto area from

the

fifteenth

through

the

sixteenth centuries;

the

kuni ikki, larger federations com-

posed chiefly of warriors

who

hoped to carve out spheres of autonomous

control; and the Ikko ikki, confederations associated with the Honganji

branch

of

the True Pure Land sect (Jodo Shinshu).

Under these unsettled conditions, the aristocratic houses and temple

headquarters that

had

held the highest level

of

proprietary rights over

private estates

(shoeri)

were displaced

by

local bushi proprietors

who

had fought their

way to

power during

the

Sengoku period. These

warriors eventually pushed aside

the

Muromachi shogunate, opening

the

way for the

appearance

of the

three hegemonic leaders,

Oda

Nobunaga (1539-82), Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-98),

and

Tokugawa

96

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INTRODUCTION 97

Ieyasu (1542-1616), who forged the military unification of Japan dur-

ing the latter half of the sixteenth century. The elaboration during the

seventeenth century of

a

strong, unified political structure based on an

unchallengable military hegemony also unleashed new forces that gen-

erated their own enormous consequences, ushering in what Japanese

historians commonly call the

kinsei

period, or what Western historians

refer to more often as the early modern age.

Historians have expounded a number of interpretations to account

conceptually for how the two processes, the one social and economic

and the other military and political, worked together to produce the

kinsei

society. Among the most influential of these interpretations has

been Nakamura Kichiji's refeudalization thesis, presented in the

1930s.

1

Nakamura focused on the relationships between warrior lords

and their retainers, both in the medieval and Tokugawa periods, and

he concluded that the

kinsei

age witnessed the reformulation under the

Tokugawa shogunate of the essential components of medieval feudal-

ism in a more politically stable and highly organized form.

In the decades following World War II, Araki Moriaki challenged

this idea with his theory of a "revolution into feudalism."

2

Working

with documents that presented an opportunity to analyze the structure

of familial-based agricultural household units, Araki argued that the

medieval

shoen

system owed its existence to what he termed the "patri-

archal slave system"

(kafuchoteki

doreisei).

But, he claimed, Tokugawa

society was organized differently and was characterized by the appear-

ance during the seventeenth century of an agricultural system depen-

dent on labor supplied by the Japanese equivalent of serfs

(nodo).

This

shift from a slave to a serf system, Araki contended, meant that true

feudalism first appeared in Japan only during the age of

the

Tokugawa

shogunate.

More recently a third interpretation that has shaped the contours of

scholarly debate has been offered by Miyagawa Mitsuru.

3

Like Araki,

Miyagawa found his scholarly inspiration in village sources, and he

agreed that medieval society was characterized by a serf system and

that feudalism prevailed in Japan during the Tokugawa period. But

Tokugawa society, he believed, relied not on true serfs but, rather, on

what he called

reino,

a class of partially dependent, partially indepen-

dent, small-scale serflike families. Consequently, to distinguish Miya-

1 Nakamura Kichiji, Bakuhan taisei ton (Tokyo: Yamakawa shuppansha, 1972).

2 Araki Moriaki, Bakuhan taisei shakai no

seiritsu

to kozo (Tokyo: Ochanomizu shobo, 1959).

3 Miyagawa Mitsuru, Taiko

kenchi

ran,

3 vols. (Tokyo: Ochanomizu shobo, 1957-63).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

98 CONSEQUENCES OF UNIFICATION

gawa's concept of historical change from that of Araki, we may refer to

his ideas as a theory of "evolutionary feudalism."

American scholarship, of course, has been influenced by the theo-

ries developed by Japanese researchers.

4

Yet it is important to note also

that Western historians who work on Japan have independently con-

structed their own frameworks of analysis and that these in turn have

had their own impact on Japanese scholarship. One particularly promi-

nent and powerful idea has been to use the term "early modern" to

refer to the kinsei period, thus avoiding the Marxist categories of

analysis favored by many Japanese and, at the same time, drawing

attention away from the period's feudal aspects and toward those long-

term trends related to the emergence of the modern Japanese state and

economy after 1868.

5

This chapter will look closely at the events of the late sixteenth

century, the pivotal transitional years that separated the

chusei

from

the kinsei epoch. From the evidence that will be presented, it should

become obvious that many continuities linked the two ages. But it

should be equally evident that enormous changes surged through the

transition years and that the evidentiary scales tilt more to the side of

dissimilarity than similarity. The social and economic trends observed

in the late medieval period did not extend, undisturbed, into the

kinsei

period, nor did Tokugawa society merely represent a reconstruction of

medieval conditions. Indeed, the medieval and the Tokugawa systems

are so dissimilar that they should be conceived of

as

entirely different

societal types, and emphasis should be placed on the distinct character-

istics of each epoch. Such an understanding requires a clear evaluation

of

how

the early modern society was molded in the cauldron of change

during the late sixteenth century.

6

4 See, for instance, Edwin O. Reischauer's reliance on the concept of refeudalization in his

Japan: The Story of a Nation, 3rd ed. (New York:

Knopf,

1981), pp. 78-86.

5 See, for instance, John Whitney Hall, "Feudalism in Japan - A Reassessment," in John W.

Hall and Marius B. Jansen, eds., Studies in the Institutional History of Early Modem Japan

(Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1968). Some of the most promising research on

the major questions concerning the transition from the medieval to the Tokugawa period is

contained in John W. Hall, Keiji Nagahara, and Kozo Yamamura, eds., Japan Before Toku-

gawa: Political Consolidation and Economic Growth, 1500-1630 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton

University Press, 1981); and George Elison and Bardwell L. Smith, eds.,

Warlords,

Artists, &

Commoners:

Japan in the Sixteenth

Century

(Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1981).

6 For an introduction to the institutional changes of the late sixteenth century, see the following

by Wakita Osamu, Kinsei

hokensei seiritsu shiron

(Tokyo: Tokyo daigaku shuppankai, 1977);

"The Kokudaka System: A Device for Reunification," Journal of Japanese Studies 1 (Spring

1975);

"The Emergence of the State in Sixteenth Century Japan: From Oda to Tokugawa,"

Journal of Japanese Studies 8 (Summer 1982): 343-67; and (with James L. McClain), "The

Commercial and Urban Policies of Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi" in Hall et al.,

eds.,

Japan Before Tokugawa, pp. 224-47.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

LAND SURVEYS AND THE EARLY MODERN PEASANTRY 99

THE TAIKO LAND SURVEYS AND THE EARLY MODERN

PEASANTRY

The expansion of the productive capacity of agriculture was the key-

stone supporting the economic foundations of Japan's early modern

society. Agricultural productivity had been increasing even during the

fourteenth century, especially in the Kinai region around the ancient

imperial capital of Kyoto. Initially, the prime

movers

behind

this

expan-

sion were the major proprietors, who

financed

large-scale land develop-

ment projects, and influential peasants, who were active on a smaller,

more local scale. In the capital area the redevelopment of

fields

devas-

tated by warfare and neglected during the fifteenth century boosted

overall yields. The opening up of entirely new

fields

also was common

in the Kinai environs. On this expanding land base, technological ad-

vances increased productivity, as did the spread of certain agricultural

innovations such as double cropping. A commercial economy also be-

gan to develop, as evident in the growth of towns and periodic local

markets. Elements of this commercial economy soon began

to

penetrate

the rural villages. Documents from Tara

shoen

in Wakasa, for instance,

reveal how farmers commuted almost daily to the nearby port town of

Obama to sell their produce. Another index of commercial growth was

the increased payment of the annual land tax in cash rather than pro-

duce.

Although this sort of economic development was at

first

the work

of rural entrepreneurs, eventually the proprietary lords also attempted

to promote commerce in their country estates.

7

The spread of the commercial economy into agricultural villages

had various consequences. Some village landlords

{kajishi

jinushi)

withdrew from the active management of fields and lived on the land

rents that they collected from the peasants, and other landlords kept

a labor force of subordinate personnel in a serflike condition. The

more commercialized economy benefited some cultivators, but it

caused others to fall into economic ruin, and many fled to nearby

cities and port towns, where they became day laborers, menials, or

beggars.

8

But on the whole, the trend was toward greater security for

7 For additional details concerning economic developments, see Kozo Yamamura, "Returns on

Reunification: Economic Growth in Japan 1550-1650," in Hall et al., eds., Japan Before

Tokugawa, pp. 327-72.

8 For further details, see Wakita Haruko, "Muromachi-ki no keizai hatten" in Koza Nihon

rekishi, vol. 7 (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1976), as well as the article by Keiji Nagahara (with

Kozo Yamamura), "The Sengoku Daimyo and the Kandaka System"; and Gin'ya Sasaki (with

William B. Hauser), "Sengoku Daimyo Rule and Commerce," in Hall et al., eds., Japan

Before Tokugawa, pp. 27-63 and 125-48, respectively.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

100 CONSEQUENCES OF UNIFICATION

the peasant landholder. For instance, the designated portions to in-

come (shiki) that were based on one's function within the

shorn

sys-

tem, such as the landholder, peasant, and cultivator portions, became

legally defined entitlements. The peasants' rights to possess land also

were strengthened. The end result of these developments was that

ordinary farmers gained a great deal of influence within their village

communities and then went on to form confederations in order to

secure a greater degree of control over the political and economic

spheres of local life.

During the sixteenth century, two forces appeared to be in competi-

tion: the expanding autonomy of village communities, allied in ikki

organizations, and the opposing desire of military lords to establish

secure domains. These conflicting goals were resolved under the early

modern political order by adopting certain fundamental institutions

such as the nationwide cadastral survey, the separation of the warrior

and farming classes, and the kokudaka system of land-tax manage-

ment. The land policies begun by the Sengoku daimyo were co-opted

and carried out on a broader, more national scale by Oda Nobunaga.

But the perfection of early modern rural administration was not

achieved in his lifetime, and the institutional structure of rural admin-

istration took final shape only under the Hideyoshi and Tokugawa

regimes.

The main objective of both the Sengoku diamyo as regional over-

lords and Oda Nobunaga as the emerging national hegemon was to

gain systematic control over the productive capacities of the country-

side.

In the middle of the sixteenth century, landholding, tax collect-

ing, and military service recruitment systems varied greatly from loca-

tion to location. What the lords most required was information on land

area, productive capacities, and the distribution of manpower. Such

information could be had in one of two ways, by either direct or

indirect measurement.

9

The complete details of Oda Nobunaga's land policies in his home

provinces of Owari and Mino have never been fully revealed, but in

those regions that he occupied later, Nobunaga ordered new cadastral

surveys. Usually he tried to appoint his own representatives to con-

9 In Japan, one line of interpretation sees Oda Nobunaga's administration as representing the

more completely unified authority characteristic of the early modern period and views the

Sengoku daimyo as similar to early modern daimyo. The argument presented here identifies

Nobunaga as more of a transitional figure with greater access to the elements of centralized

political authority than the Muromachi shogunate had, but still weaker than the Tokugawa

shoguns. For more details on current research, see Nagahara Keiji, ed.,Sengoku-ki

no kentyoku

to shakai (Tokyo: Tokyo daigaku shuppankai, 1976).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

LAND SURVEYS AND THE EARLY MODERN PEASANTRY IOI

duct them, but where that was not feasible, he required local lords to

submit their own land and tax reports, called

sashidashi.

However

compiled, the registers listed landholdings and the amounts of annual

tax customarily collected.

10

Under Nobunaga, direct land surveys were

conducted in Ise, Echizen, Harima, Settsu, and Tango provinces, and

the land-tax submission reports were collected in Omi, Yamashiro,

Yamato, and Izumi. Because the cadastral surveys were direct on-site

investigations, they included as much detail as the overlord deemed

necessary. Although the land-tax reports were submitted by individual

proprietors, who in turn relied on records supplied by village commu-

nities,

they too contained a considerable amount of detail. Some extant

sashidashi

from the Yamato region in the 1580s, as well as one from

Kofukuji, show that the surveys were based on actual plot-by-plot

field inspections by the proprietor and listed precisely the area of the

fields, the tax imports, and the cultivators' names.

11

The cadastral registers and land-tax submissions became the docu-

mentary foundations on which Oda Nobunaga based his claim to supe-

rior powers of control over provincewide units. The nature of his

authority was basically identical to the administrative and proprietary

powers that the Sengoku daimyo exercised within their holdings. In

other words, they had fashioned what were legally called "complete

proprietorships" (ichien chigyo or isshiki shihai). This meant that

within their domains, the daimyo, as proprietary lords, held the right

to assign fiefs, command military forces, and exercise police and judi-

cial authority. Of

course,

Nobunaga's political administration pursued

a more complete expression of these powers, in time asserting a rudi-

mentary central authority over the individual Sengoku daimyo that

was much stronger than that of the preceding Muromachi shogunate.

Oda Nobunaga was able to impose his claims to this superior author-

ity while at the same time assigning provincial lands as fiefs to the

more important members of his houseband, such as Shibata Katsuie

10 Those persons who discovered unregistered fields or who developed new paddy had to

conduct a survey or submit a sashidashi report. Because Owari and Mino constituted the

central core of Nogunaga's holdings, he was particularly anxious to impose his authority over

outlying areas within those provinces, but even at present, we have discovered no complete

set of land survey records for this region.

11 The cadastral surveys were carried out on a province-by-province basis, and the surveyed

land was granted to proprietors

(ryoshu)

as fiefs (chigyo). In other words, the Oda administra-

tion could lay claim to the rights to control land, possess land, and distribute it as fiefs. The

sashidashi were reports submitted by individual proprietors and, consequently, served as

confirmations of fief grants. In these cases, too, the Oda administration claimed superior

rights, but the sashidashi were different from the cadastral surveys in terms of thoroughness.

This was probably because the sashidashi reports came from areas where the proprietary

rights were claimed by temples and aristocrats.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

102 CONSEQUENCES OF UNIFICATION

and Hashiba (Toyotomi) Hideyoshi. Nobunaga authorized these re-

tainers to exercise proprietary rights, especially the collection of dues

and labor

services.

But there still were regional procedural differences.

Within any one unit of control, the means of measuring productive

capacity (taka) had been standardized, but as yet no one method was

applied uniformly across all of Japan. For instance, in the five prov-

inces around Kyoto - Yamashiro, Yamato, Settsu, Kawachi, and

Izumi - as well as in Omi, Echizen, Harima, and Tamba, grain was

measured in terms of

koku.

However the kandaka system, in which

dues and imposts were expressed in units of cash, was used in Owari,

Mino,

and Ise. Both systems indicated the actual amount of tax due in

goods and services from the land. In practice, the annual rents col-

lected under the kandaka system included some payments in grain,

and portions of the so-called

kokudaka

imposts could also be paid in

cash.

Despite Nobunaga's effort to exercise total control over the land

base,

the fact that he was obliged to accept

sashidashi

submissions

showed that he was still far from achieving this goal. Moreover, the

grant of a fief to a retainer

(kashin)

often merely reconfirmed existing

rights that the retainer already claimed over those units of land. Fiefs

were also granted in which temples and Kyoto-based proprietors con-

tinued to exercise their old

shoen-derived

prerogatives. Consequently,

despite surface changes, the old patterns of land possession often con-

tinued to prevail. In the same way, although Nobunaga imposed the

burdens of the tax and corvee levies on the peasants, he also recog-

nized the landlord-tenant relationships that already existed in peasant

society. Thus in several documented cases he affirmed that the

myoshu,

the man who held the plot of land and was responsible for paying the

dues levied against it to the overlord, could continue to receive his

customary profits and the traditional set of miscellaneous dues (ko-

mononari)

imposed on the families living on his holdings.

Following the death of Nobunaga in 1582, Toyotomi Hideyoshi

imposed his own hegemony over the country. At the outset of his

takeover, the pattern of land rights remained as they had been under

Nobunaga, a complicated mix of claims by local military proprietors.

The kokudaka system, a product of the cadastral survey ordered by

Toyotomi Hideyoshi and known as the Taiko

kenchi,

cut across this

welter of competing claims and both simplified and clarified rights of

land possession. Hideyoshi was able to carry out a nationwide survey

because he had assembled more military power than Oda Nobunaga

had and thus could extend stronger claims of national legitimacy. In

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

LAND SURVEYS AND THE EARLY MODERN PEASANTRY IO3

particular, Hideyoshi was able to justify his action on the basis of

having received from the emperor the famous injunction: "You shall

exercise administrative functions over the more than sixty provinces of

Japan in accordance with what is best for the land and the people."

12

Thus,

Hideyoshi's survey might appropriately be called a "public

survey over the entire realm" (tenka no

kenchi).

As such, it literally

remade the land relationships that had existed up to that time.

The early modern form of landed enfeoffment rested on new princi-

ples of land possession as denned by this Taiko cadastral survey. At the

highest level, all proprietary rights became securely lodged in the

hands of the national hegemon. Now all bushi, and even temples and

Kyoto-based aristocrats, could hold territory only as grants-held-in-

trust

(azukarimono)

confirmed by the vermilion seal of Hideyoshi.

Moreover, certain rights and responsibilities concerning these hold-

ings could be reassigned to lower elements in the power structure. A

clause in the famous "Bateren expulsion decree" that Hideyoshi issued

in 1587 banning Christianity and ordering the Jesuits to leave Japan

within twenty days inadvertently confirmed this practice by stating:

"Fiefs granted to vassals belong ultimately to the state, that is, to the

provinces and districts, and each vassal holds the land in trust for the

present only. Each vassal must obey the laws of the realm

{tenka)."

11

This use of the concept of land held in trust for the overlord became

the basis for the new centralization of

power.

The rights to collect the

grain tax and corvee levies and to exercise judicial judgment, which

had been divided under the

shoen

system, were now pulled together

and held by a single authority.

To conduct the Taiko survey, inspectors

(bugyo)

were dispatched to

the provinces where they were ordered to investigate each parcel of

land in each village. This practice of relying solely on officials dis-

patched by the governing authority was a fuller declaration of the

powers of overlordship than Nobunaga had been able to develop.

Hideyoshi's intentions in this regard were revealed initially in 1582,

when he carried out surveys in Yamashiro without first receiving

sashidashi

reports. This new trend became more evident in the 1584

cadastral survey documents for some portions of Omi and then be-

came the normal method of conducting cadastral surveys from the end

of the decade of the 1580s.

12 "Shimazu-ke monjo," no. 345 in DaiNihon

komonjo:

Shimazu ke

monjo,

vol.

1

(Tokyo: Tokyo

daigaku shuppankai, 1942), p. 342.

13 See the "Matsuura-ke monjo." A reproduction of the document is contained in the lezusukai

Nihon nempyo, vol. 2 (Tokyo: Yush6do shoten, 1969), located in the Matsuura Museum.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

104 CONSEQUENCES OF UNIFICATION

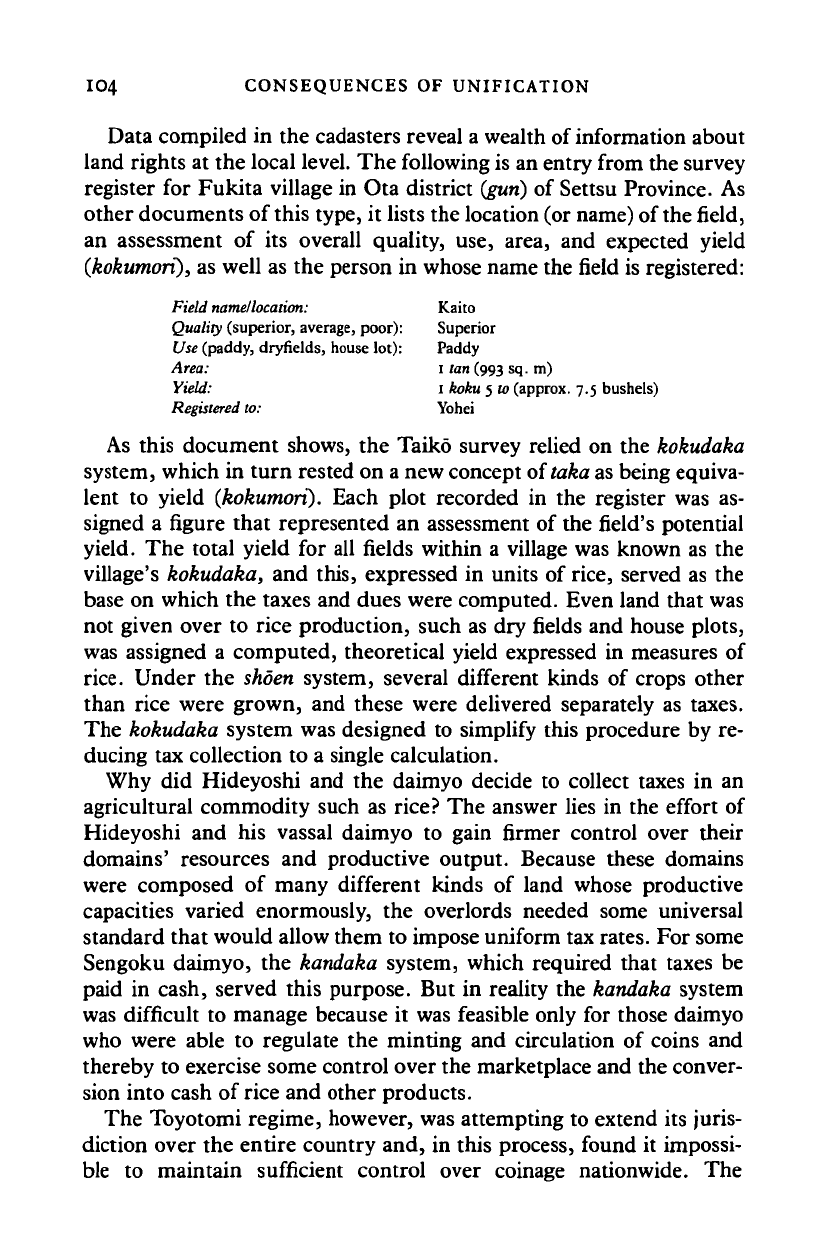

Data compiled in the cadasters reveal a wealth of information about

land rights at the local level. The following is an entry from the survey

register for Fukita village in Ota district

(gun)

of Settsu Province. As

other documents of this type, it lists the location (or name) of the field,

an assessment of its overall quality, use, area, and expected yield

(kokumon),

as well as the person in whose name the field is registered:

Field name/location:

Kaito

Quality

(superior,

average,

poor):

Superior

Use

(paddy,

dryfields,

house

lot):

Paddy

Area:

I

tan (993

sq. m)

Yield:

1 koku

5 to

(approx.

7.5

bushels)

Registered to: Yohei

As this document shows, the Taiko survey relied on the kokudaka

system, which in turn rested on a new concept oitaka as being equiva-

lent to yield (kokumori). Each plot recorded in the register was as-

signed a figure that represented an assessment of the field's potential

yield. The total yield for all fields within a village was known as the

village's kokudaka, and this, expressed in units of rice, served as the

base on which the taxes and dues were computed. Even land that was

not given over to rice production, such as dry fields and house plots,

was assigned a computed, theoretical yield expressed in measures of

rice.

Under the

shoen

system, several different kinds of crops other

than rice were grown, and these were delivered separately as taxes.

The kokudaka system was designed to simplify this procedure by re-

ducing tax collection to a single calculation.

Why did Hideyoshi and the daimyo decide to collect taxes in an

agricultural commodity such as rice? The answer lies in the effort of

Hideyoshi and his vassal daimyo to gain firmer control over their

domains' resources and productive output. Because these domains

were composed of many different kinds of land whose productive

capacities varied enormously, the overlords needed some universal

standard that would allow them to impose uniform tax rates. For some

Sengoku daimyo, the kandaka system, which required that taxes be

paid in cash, served this purpose. But in reality the kandaka system

was difficult to manage because it was feasible only for those daimyo

who were able to regulate the minting and circulation of coins and

thereby to exercise some control over the marketplace and the conver-

sion into cash of rice and other products.

The Toyotomi regime, however, was attempting to extend its juris-

diction over the entire country and, in this process, found it impossi-

ble to maintain sufficient control over coinage nationwide. The

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008