The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 4: Early Modern Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

WAR AND PEACE 265

and mariners

[sendo

kako]" drafted the previous year had been so

"sorely afflicted" that "the greater half of them died."

40

The service on

which they had suffered such terrible losses was Hideyoshi's war of

aggression in Korea.

WAR AND PEACE

The background of Japanese

aggression

in Korea

To the Koreans, Hideyoshi's invasion of their country meant the

second coming of the

bahan

plague and the biggest wako raid of all.

In contrast, the Japanese participants who wrote accounts of the

invasion - men of varied backgrounds, from the appropriately named

Yoshino Jingozaemon, a samurai of Matsuura, to Shukuro Shungaku,

a Zen monk in the retinue of the general Kikkawa Hiroie

(1561-

1625) - invariably invoked the myth of a primordial conquest of

Korea by Japan's empress Jingu as a historical precedent that justi-

fied their venture.

4

'

Hideyoshi himself claimed a sanction that was even more grand: In

broadcasting his plans to extend his dominion overseas, he asserted

that the will to conquer had been bestowed on him by Heaven.

42

To

the king of Korea, he wrote in 1590 that he was conceived when the

wheel of the sun entered his mother's womb in a dream, a sure sign

that the glory of his name should pervade the Four Seas, just as the

sun illuminates the universe. Indeed, he had no purpose but to spread

his fame throughout the Three Countries of Japan, China, and Korea.

Now that he had pacified and prospered Japan and demonstrated his

invincibility there, he would invade China to introduce Japanese cus-

toms and values to that country, and he wanted the Koreans to lead the

way.

43

Hideyoshi's ambassadors did their best to soften the rude force of

his demand, by insinuating that the last phrase required the Korean

40 Hideyoshi to the home-province resident lieutenants (rusui) of Hashiba Kikkawa Jiju

[Kikkawa Hiroie], dated [Bunroku 2O2.5, in Dai Nihon komonjo, ieiaake 9: Kikkawa-ke

monjo, vol. I, no. 783, pp.

750-1.

41

Yoshino

Jingozaemon oboegaki, in Zoku gunsho ruiju, XX-2 (Tokyo: Zoku gunsho ruiju

kanseikai, 1923), 591:378;

Shukuro

kd, ibid, XIII-2 (1926), 356:1003.

42 Kampaku of Japan to Lesser Ryukyu (i.e., the Philippine Islands), dated Tensho 19

(1591)9.15, Murakami Naojiro, ed., Ikoku ofuku

shokanshu,

Zotei ikoku nikki sho (Tokyo:

Sunnansha, 1929), p. 29.

43 Kampaku of Japan to King of Korea, dated Tensho 18 (1590). 11.-, Zoku

zenrin

kokuhoki,

in

Zoku

gunsho

ruiju, XXX-i (1925), 881:404. Curiously enough, Wang Chih was another who

was conceived when a "great star" entered his mother's womb in a dream; see Ch'ou-hai fu-

pien,

pt. 9, f. 24.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

266 JAPAN'S RELATIONS WITH CHINA AND KOREA

government to do no more than clear the road to China for the Japa-

nese (that is, grant them transit rights through Korea) or - milder

yet - to smooth the path for a resumption of Japanese relations with

China. But the Koreans would be neither fooled nor intimidated.

They refused on principle to become party to an assault on the country

that was their suzerain. To be sure, although they expressed them-

selves in terms of filial respect when they spoke of their duty to China,

they also had a healthy fear of this parent; yet they trusted China to

come to the aid of Korea, if need be.

44

Korea, in short, was comfort-

able with the international order of East Asia headed by China and

sought security from it. Hideyoshi, however, wanted to overthrow that

system. If Korea did not cooperate with him - and by the middle of

1591 it had clearly indicated that it would not - then it would have to

suffer the consequences.

The notion of

a

continental invasion was not a thought that came to

Hideyoshi suddenly. Indeed, in view of the prevalent image of

Hideyoshi as a megalomaniac, which is based in large part on his

foreign aggression, it is interesting to note that the idea was first

broached not by him but by his predecessor. It was Oda Nobunaga

who proclaimed in 1582 his intention to subdue China by force of arms

once he had made himself "absolute master of all the sixty and six

reigns of Japan."

45

In other words, a vision of the conquest of China

was the common conceit of the two great unifiers, and both saw it as

an extension of the conquests through which Japan was being sub-

jected to their regime. For Nobunaga, the vision came to nothing

when he was assassinated with less than half

his

Japanese objective in

his grasp. For Hideyoshi, it grew less fanciful and more concrete as the

process of Japan's unification advanced under his direction.

Significantly enough, the earliest-known documentary evidence of

Hideyoshi's bellicose intentions toward the continent comes from

1585,

that triumphal year when his armies were victorious in three

different regions of Japan, when he won the appointment to the lofty

44 The arrival of Hideyoshi's letter in Korea, the efforts of his envoys, the priest Keitetsu Genso

and So Yoshitoshi, the daimyo of Tsushima, to explain away the main issue, and the Korean

court's reactions to these diplomatic proceedings are described in detail in Sdnjo

SogyOng

Taewang sujong sillok, pt. 25, ff. 2-17V, entries for the third to sixth months of Sonjo 24

(1591):

Chosdn wangjo sillok, vol. 25 (1957), pp. 601-8. The response sent by the Korean

court to Hideyoshi may be found in f. 141% p. 607. See also Chosen Sotokufu Chosenshi

henshukai, ed., Chosenshi, 4th series, vol. 9 (Keijo: Chosen insatsu kabushiki kaisha, 1937),

pp.

410—20.

45 Frois to General SJ, dated Cochinoccu (Kuchinotsu in Hizen), November 5, 1582, Cartas qve

os Padres, vol. 2, f. 63V. Also in Frois, Historia, pt. 2, chap. 40, ed. Wicki, vol. 3 (1982), p.

336;

Matsuda and Kawasaki, trans.,

Furoisu

Nihonshi, vol. 5 (1978), p. 138.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

WAR AND PEACE 267

aristocratic post of kampaku (imperial regent), and when the prospect

of a country unified under his aegis first appeared as a real possibility.

We find the mention in a letter in which the idea of a conquest of all

Japan is coupled with that of China.

46

In 1586, as he planned the

subjugation of the Shimazu and the pacification of Kyushu, Hideyoshi

repeatedly referred to China and Korea as though to invade them were

a course of action that would follow naturally from an occupation of

southwestern Japan.

47

By April 1587, when Hideyoshi departed Osaka on his Kyushu

campaign, the scope of his ambitions had apparently increased along

with their notoriety: There was talk of

a

"grand design" on his part to

proceed onward and "slash his way" into Korea, China, and South

Barbary (presumably somewhere in the region of the Indies or even

farther, where pepper and the Portuguese came from).

48

That Hide-

yoshi, whose knowledge of world geography cannot have been great,

indeed harbored a far-flung design that included even India would

later become evident from his own words, but the immediate after-

math of the conquest of Kyushu was not yet the time to embark on a

foreign venture. A great external exploit that would crown and safe-

guard his internal accomplishments was what Hideyoshi envisioned,

but it had to be postponed while there were still important matters to

be taken care of at home. The east and the north of Japan were as yet

unconquered.

Accordingly, the machinery for the invasion of the mainland was not

set in motion until 1591, when the provinces of Mutsu and Dewa, the

46 Hideyoshi

to

Hitotsuyanagi Ichinosuke (Sueyasu), dated [Tensho 13.19.3.

See

Iwasawa

Yoshihiko, "Hideyoshi

no

Kara-iri

ni

kansuru monjo,"

in

Nihon rekishi

163

(January 1962):

73-75-

According

to

Chosen seibatsuki,

a

history

of the

Korean invasion

by the Neo-

Confucian scholar Hori Kyoan (1585-1642), Hideyoshi

on the

occasion

of

his departure

for

the Chugoku front against

the

Mori

in 1577

asked Nobunaga

for the

explicit permission

to

extend

his

conquests

as far as

Korea

and

China. Hideyoshi supposedly

was

concerned lest,

without such orders,

he be

accused

of

bahan

activity. Nobunaga laughed

and

then approved

all

of his

campaign plans. This work, however,

is not a

primary source,

and the

anecdote

cannot

be

accepted without question.

See

Nakamura, Nissen kankeishi,

vol. 2

(1969),

pp.

256-7.

47

See, for

example, Hideyoshi's vermilion-seal letters

to

Mori

Uma no

Kami (Terumoto), dated

[Tensho

14.] 4.10, and to

Ankokuji (Ekei), Kuroda Kageyu (Yoshitaka),

and

Miyagi Uhyoe

Nyudo (Tomoyori), dated [Tensho

14.] 8.5, in Dai

Nihon

komonjo,

lewake

8:

Mdri-ke monjo,

vol.

3, nos.

949-50,

pp.

227-31. Also

see

Frois's accounts

of the

Jesuit Vice-Provincial

Gaspar Coelho's audience with Hideyoshi

on May 4, 1586,

when Hideyoshi asked the Jesuits

to negotiate

for him the

charter

of

two well-equipped

and

well-officered Portuguese ships

for

his planned invasion

of

Korea

and

China: Frois

to

Alexandra Valignano

SJ,

dated Ximo-

noxequi, October

17,

1586, Cartas qve

os

Padres,

vol. 2, ff.

175V-7V; and Frois, Historia,

pt. 2

(B),

chap.

31, ed.

Wicki,

vol. 4, pp.

227-35; Matsuda

and

Kawasaki, trans., Furoisu

Nihonshi,

vol.

1 (1978,

4th

printing),

pp.

202-18.

48 Takeuchi Rizo,

ed.,

Tamon'in

nikki,

vol. 4, in

Zoho zoku

shiryo

taisei (Kyoto: Rinsen shoten,

1978),

p. 68;

entry

for

Tensho 15.3.3.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

268 JAPAN'S RELATIONS WITH CHINA AND KOREA

northernmost reaches of Honshu, were finally subdued - all of Japan

thereby becoming subject to Hideyoshi's authority - and the task of

unification was completed. In the eighth month of that year, as his

nephew and deputy Hashiba Hidetsugu (1568-95, soon to become the

imperial regent of Japan) was reducing to fealty the last of

the

northern

barons, Hideyoshi took two grave steps: First, he issued the famous

edict that prohibited the change of status from samurai to townsman

or farmer and forbade farmers to abandon their calling for a trade or

for job work. Thereby Hideyoshi enacted the basic definition of a

domestic social order that would last 280

years.

Second, he set the date

for the invasion of the mainland (to be the first day of

the

third month

of the following year) and ordered the preparation of a headquarters

and staging area at Nagoya in the Matsuura region of Hizen Province,

at the point of Kyushu nearest to the mainland.

49

It is clear that one of Hideyoshi's principal aims in invading the

mainland was to demonstrate the unassailable power of Japan's na-

tional hegemon. But he wished to attain this goal not only externally,

at the expense of the Koreans and Chinese; surely as important in his

plans were the internal targets, the daimyo of Japan and the people of

their domains. The object was to bend them to the unifier's will

through the mobilization of their resources for the invasion, and they

were put to tremendous exertions even before the first Japanese soldier

crossed the strait of Tsushima to the continent. First, Hideyoshi's

headquarters for the invasion, a huge two-ring fortress, had to be

constructed from the ground up at Nagoya. This was accomplished in

little more than six months by an enormous labor force rounded up by

the lords of Kyushu. Having erected the elaborately ramparted and

lavishly decorated castle, the peers of the Japanese realm were ordered

to build their own residences in its vicinity, and a sizable castle town

grew up around it. To this nonesuch in Kyushu, Hideyoshi traveled in

style through twenty luxurious way stations prepared at his behest by

daimyo along the route from Kyoto. These all were expensive and

burdensome undertakings, and it was not Hideyoshi but the daimyo

and their populations who shouldered the costs and the burdens.

According to the Jesuit chronicler Frois, the daimyo groaned at

these impositions no less than at the thought that in taking ship for

49 Ota Gyuichi, who knew Hidetsugu, wrote his name as Hidetsugi, but historians have not

followed his example. The edict prohibiting the change of status, dated Tensho 19.8.21, is

found in many sources, such as Mori-ke monjo, vol. 3, no. 935, pp. 216-17. An early

statement regarding concrete preparations for the invasion of China is the letter from Ishida

Moku Masazumi to Sagara Kunai no Daibu (Nagatsune), dated [Tensho 19.] 8.23, in Dai

Nihon komonjo, iewake 5: Sagara-ke

monjo,

vol. 2, no. 699, pp. 117-18.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

WAR AND PEACE 269

Korea, they would be going to their deaths. There were rumors that a

rebellion would surely spring up and put an early end to Hideyoshi's

plans,

but none among the daimyo wanted to bell the cat: They all

were terror stricken and rendered incapable of conspiracy by the ty-

rant. Even as he intimidated and

fleeced

the Japanese lords, Hideyoshi

sought to console them with expectations of rewards in Korea and

China. For instance, he apparently promised three Chinese provinces

to the "Christian daimyo" Dom Protasio Arima (Harunobu, the lord

of Arima in Hizen, 1567-1612). It is likely that, as Frois states, the

recipients of such assurances of future favor, profuse though they may

have been with expressions of gratitude to Hideyoshi's face, in actual-

ity wished nothing more than to hold on to their pieces of their native

land and were scared stiff of their master's talk of a transfer to such

distant if dilated dominions.

50

To be sure, there were also those like

the lord of Saga in Hizen, Nabeshima Naoshige (i538-1618), who

actively solicited reinvestment with a fief in China on the not-

unreasonable grounds that his native province had close traditional

ties with that country - "because a great many of the people of the

Hizen seacoast have been over there on

bahan

business and are quite

used and attached to China."

51

Japanese historians have variously sought to explain the reasons for

Hideyoshi's overseas venture. Their opinions range from that ex-

pressed by Tanaka Yoshinari, who wrote in 1905 that it was a type of

manifest destiny - a "tidal force" - that drove the Japanese to expand

overseas, to the more dyspeptic notion of Suzuki Ryoichi, who sug-

gested in the early 1950s that the invasion of the mainland proceeded

naturally from Hideyoshi's tyrannical character and that, in his urge to

become an absolute ruler, he first used the daimyo to quash popular

energies within Japan and then directed their aggressive impulses to-

ward the neighboring country.

52

Suzuki's interpretation should at least

be amended to allow for Hideyoshi's, that spectacular parvenu's, extra-

50 See Frois, Historia, pt. 3, chap. 51, ed. Wicki, vol. 5 (1984; note that the running headline of

this volume, "Segunda pane," conflicts with its half-title, p. 1, "Terceira Pane da Historia de

Japam"), pp. 382-6; Matsuda and Kawasaki, trans.,

Furoisu

Nihonshi, vol. 2 (1977), pp.

160-6. Cf. Tamon'in nikki, vol. 4, pp. 337, 339-40, entries for Tensho 20 (i592).2.28 and

3.15. A rebellion did occur in 1592, but it was abortive. The ringleader, Umekita Kunikane,

a vassal of the Shimazu, was killed before he could accomplish anything. His wife was burned

before the assembled grandees in a garden of Nagoya Castle, "pour encourager les autres."

The episode caused a delay in the dispatch of Satsuma troops to Korea.

51 Kato Kiyomasa to Natsuka Masaie and Mashita Nagamori, Tensho 20.6.24; quoted exten-

sively by Nakamura, Nissen kankei shi, vol. 2, p. 262.

52 The major interpretations are synopsized by Kitajima Manji,

Chosen

nichinichiki,

Korai nikki:

Hideyoshi no

Chosen

shintyaku to

sono rekishiteki kokuhatsu

(Nikki,

kiroku

niyoru Nihon

rekishi

sosho,

kinsei 4) (Tokyo: Soshiete, 1982), pp. 17-19.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

270 JAPAN'S RELATIONS WITH CHINA AND KOREA

ordinarily ardent desire for distinction, for this was "a social climber

whose ambition knew no limits."

53

In this context, it is interesting to speculate on the true significance

of the dispositions that Hideyoshi was inspired to make, in the flush of

his invasion's early success, regarding his future new order in Asia. In

the notorious twenty-five-article vermilion-seal letter he sent on

Tensho 20 (I592).5.i8 to the imperial regent Hidetsugu (the nephew

and adopted son he had installed as

kampaku

in Kyoto not five months

previously), Hideyoshi - if only on paper - moved the reigning Japa-

nese emperor to the Chinese capital (allotting ten provinces in its

vicinity to his support), assigned the rank of Emperor of Japan to

either one of two imperial princes (one of them, Hachijo Toshihito,

adopted by Hideyoshi as his own son), designated three of his other

adopted sons as the candidates to rule over Korea, appointed Hidet-

sugi to the post of kampaku of China (promising him a hundred-

province appanage near Peking), and put forward the names of two

adopted sons as the possible successors to that dignity in Japan.

54

But

where would that leave the paterfamilias, the man who thus disposed

over reigns, regencies, and realms with the greatest of ease? He

himself - we learn from a letter sent by his secretary on the same day

to two of the ladies of Hideyoshi's entourage - would first go to Pe-

king, but then he proposed to take up residence in Ningpo, "the

anchorage of the Japanese"; later on, he expected to conquer India.

55

What was the necessity for all these complicated moves and reassign-

ments of positions? And what role did the conqueror of Korea, China,

and India (not to speak of the lesser countries such as Ryukyu, Tai-

wan, and the Philippines, all of which Hideyoshi also threatened with

doom unless they submitted) consider worthy of himself after the final

victory? Surely the maker of emperors and kings must have envisioned

a dignity transcending all others. It is tempting to assume that the

upstart Hideyoshi, foreseeing in the subjugation of Asia the trium-

phant climax of his career, planned the ultimate legitimation for him-

53 I have discussed the aristocratization of this lowborn hegemon in "Hideyoshi, the Bountiful

Minister," in Elison and Smith, eds.,

Warlords,

Artists, &

Commoners,

pp. 223-44; quotation

from p. 233.

54 Hideyoshi to Kampaku (Hidetsugu), dated Tensho 20.5.18, in Kitajima, Chosen

nichinichiki,

pp.

67-70. It is difficult to tell what Hideyoshi meant by the term "province" (J: kuni or

koku, Ch: kuo). If it refers to something of approximately the same size as the Japanese

province, of which there were 68 in Hideyoshi's time, then the closest Chinese equivalent is

the "district" (Ch: hsien, J: ken), of which there were 1,171 in the Ming period.

55 Yama(naka) Kichi(nai) (Nagatoshi) to Ohigashisama and Okyakujinsama (Dona Madalena),

dated [Tensho 20.J5.18, in Tokutomi Iichiro, Toyowmi-shi jidai,

cho-hen:

Chosen no

eki, pt. 1,

vol. 7 oiKinsei Nihon kokumin

shi

(Tokyo: Min'yusha, 1935), pp. 453-60.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

WAR AND PEACE 27I

self as a sort of universal monarch. What he actually had in mind,

however, we shall never know, because his conquests did not get past

the first obstacle, Korea.

Hideyoshi's plans were conceived in supreme confidence and the

most abysmal want of knowledge of the conditions that the Japanese

armies would confront on the mainland. Not so much megalomania as

ignorance moved the entire enterprise. No systematic effort had been

made to gather intelligence on the countries it was proposed to sweep

into the maw (if there were Japanese books on Korea comparable to

Haedong chegukki

or on China analogous to Ch'ou-hai fu-pien, they

have not survived). Indeed, Hideyoshi's hazy knowledge of interna-

tional relations for a good while made him suffer under the delusion

that Korea was subject to Tsushima, hence causing him to insist that

the king of Korea should come to Japan in order to pay obeisance.

56

Hideyoshi invaded Korea because it lay next to China, thinking that

he could conquer China easily and that then all of the known world

would fall into his lap. What he expected to do with it - beyond,

undoubtedly, subjecting it to a round of cadastral surveys, sword

hunts,

and castle demolitions, the proven measures of Japanese

unification - is unclear. Or is the true nature of his plans revealed in

the unguarded language of the following wildly mixed metaphor? "To

take by force this virgin of a country, Ming, will be [as easy] as for a

mountain to crush an egg." India and South Barbary were next on the

list.

57

The invasion and the

first

Japanese offensive

According to the order of battle determined by Hideyoshi on Tenshd

20.3.13,

the Japanese expeditionary army was composed of 158,800

men in nine divisions.

58

Two of these divisions, 21,500 men drawn

from the provinces of Bizen, Mino, and Tango, were to be held in

reserve on the islands of Iki and Tsushima; designated to make the

56 See Nakamura, Nissen kanhei shi, vol. 2, pp. 248-9; and Kitajima, Chosen

nichinichiki,

pp.

25-6,

both citing Kyushu godoza no ki (1587) by Omura Yuko.

57 Hideyoshi to Hashiba Aki no Saisho [Mori Terumoto], dated Tensho 20.6.3, Mori-ke monjo,

vol. 3, no. 903, p. 163. In another vermilion-seal letter addressed on the same day to Mori

Terumoto, Hideyoshi calls Ming "the country of long sleeves," the samurai's standard trope

for effeminacy or genteel ineffectuality; see ibid., no. 904, p. 167.

58 See the chart set out by Kitajima,

Chosen

nichinichiki,

p. 36, on the basis of the order of battle

detailed in Hideyoshi's memorandum to Hashiba Aki no Saisho, Mori-ke

monjo,

vol. 3, no.

885,

pp. 143-8, and synopsized with the addition of naval assignments, ibid., no. 886, pp.

149-50; both documents dated Tensho 20.3.13. A total of 137,300 men may be calculated in

another order of

battle;

ibid., no. 904, pp. 164-8, dated Tenshd 20.6.3.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

272 JAPAN'S RELATIONS WITH CHINA AND KOREA

assault on Korea were contingents from Kyushu, Shikoku, and the

Chugoku region. Almost all of the daimyo of western Japan were

destined to make the crossing. Some 27,000 of Hideyoshi's own troops

garrisoned his headquarters, Nagoya; more than 70,000 levies who

had been marched to Kyushu by the eastern daimyo were disposed in

encampments around the wider periphery of that castle. Another

100,000 men from the Kinai and Tokai regions are said to have been

concentrated around Kyoto. In other words, the mobilization for

Hideyoshi's Korean venture encompassed the entire country of Japan,

whether or not the troops were directly involved in operations on the

continent. For obvious logistical reasons, however, most heavily af-

fected by the mobilization were the populations of the Kyushu daimyo

and the maritime lords - the former pirate chieftains - of the Inland

Sea and the Kii peninsula. These had to furnish five men for each 100

koku (180 hectoliters) of

rice

that the particular domain was estimated

under the kokudaka system to produce in rice yearly. Other domains

were burdened relatively less.

It should be noted that the armies mobilized by Hideyoshi in this

way were not composed entirely or even principally of members of a

warlike caste, professional soldiers, and trained fighting men, that is,

of samurai. A daimyo's quota was filled for the most part by ordi-

nary farmers and fishermen impressed into service. For instance, in

the contingent of 705 men led in the first wave of the invasion by

Goto Sumiharu (d. 1595), lord of the Goto Islands in the Matsuura

region, there were 27 mounted warriors, 40 dismounted men-at-

arms,

120 foot soldiers

(ashigaru),

and 38 soldiers who served their

officers as batmen

(kobito).

These 225, all that can be accommodated

under the label "samurai," even if one stretches the term, were out-

numbered by the 480 others identified as laborers (200) or master

seamen and common sailors (280). Whether the last group, in par-

ticular, deserves to be called innocent islanders who were shanghaied

into the invasion fleet is subject to doubt, given the past history of

the Goto Islands as a notorious lair of the wako; moreover, it would

be rash to generalize on the basis of this example alone. The muster

rolls of other daimyo do, however, suggest that no more than half of

those on the strength of a contingent drafted for service in Korea

were fighting men; the rest did construction and transport duties.

Even if the mariners were glad to carry on the piratical tradition of

their wako forbears, there is no reason to assume that the navvies

and the bearers followed along enthusiastically in the train of the

invasion armies. On the contrary, there is ample evidence of abscond-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

WAR AND

PEACE

273

ing and other forms of passive resistance by peasants who despaired

of ever coming back to their native farmlands once they heeded the

call to the war of aggression.

59

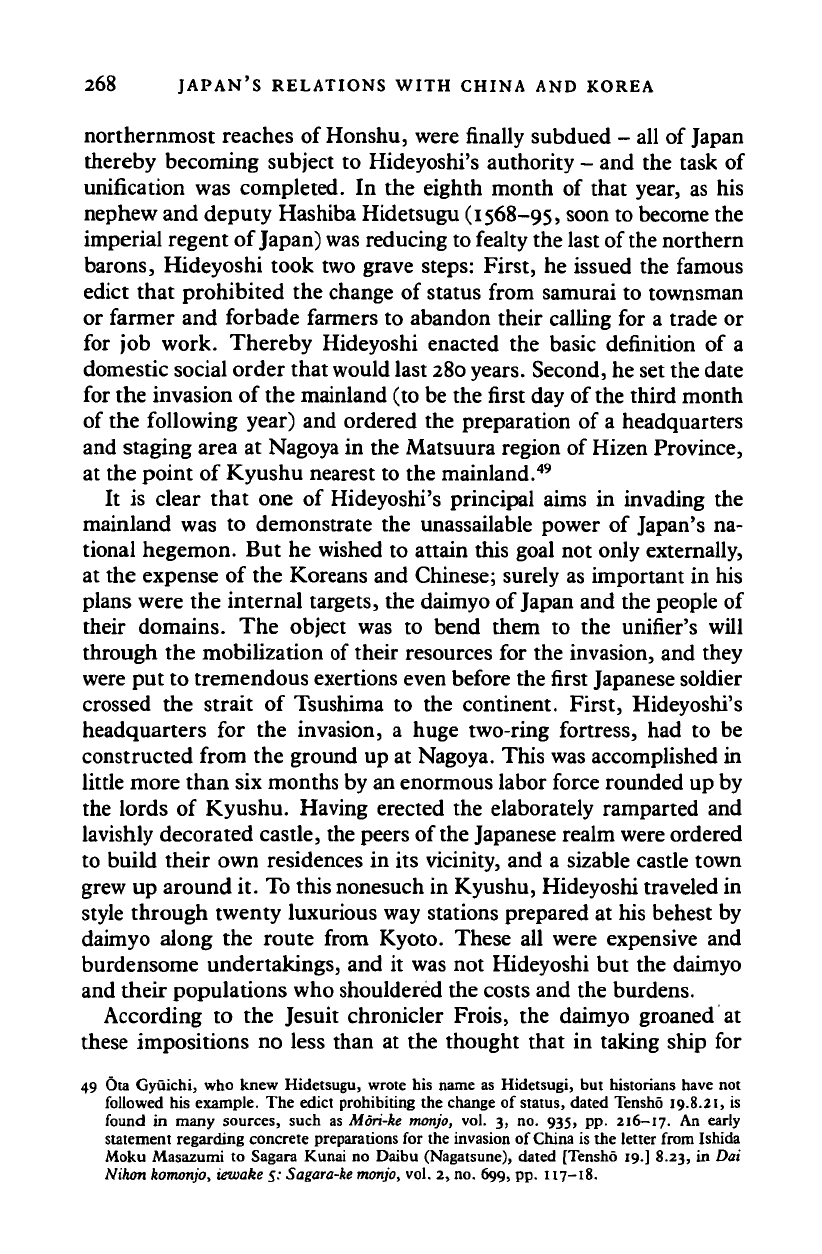

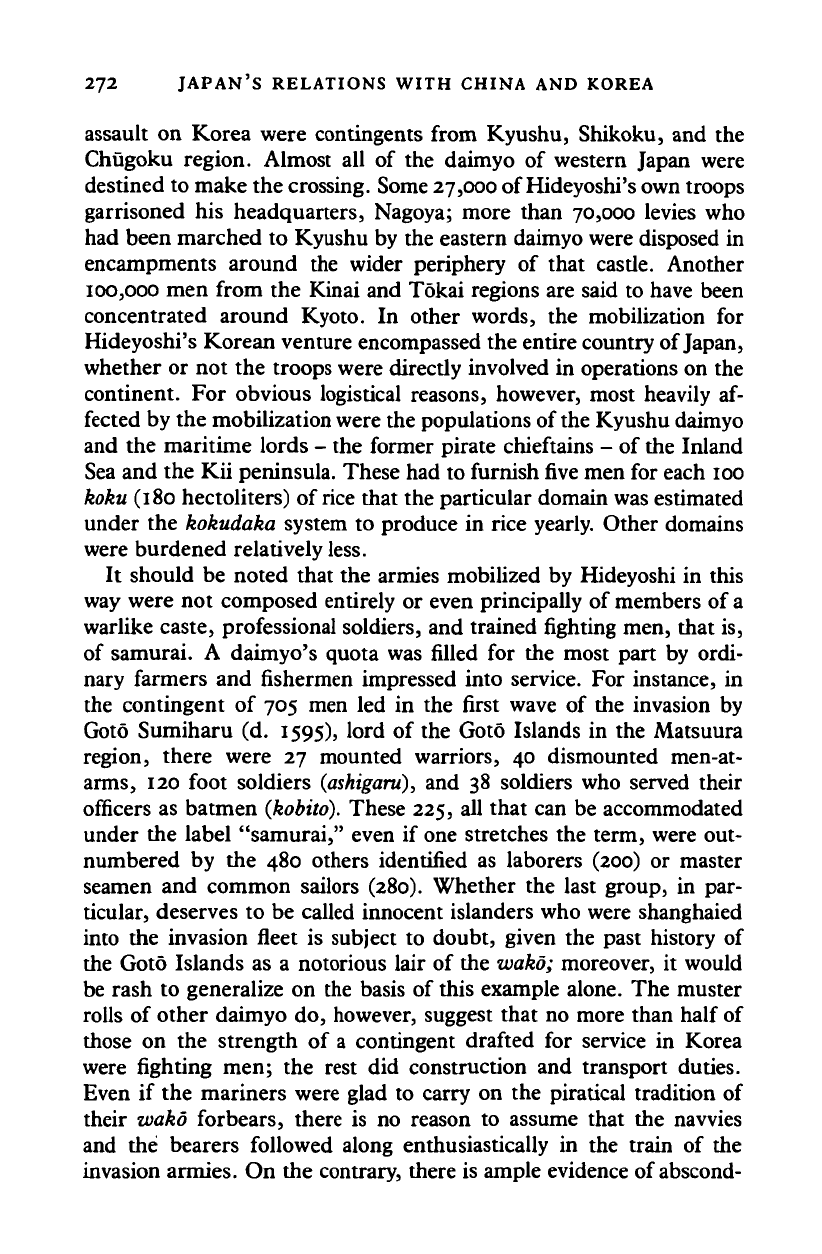

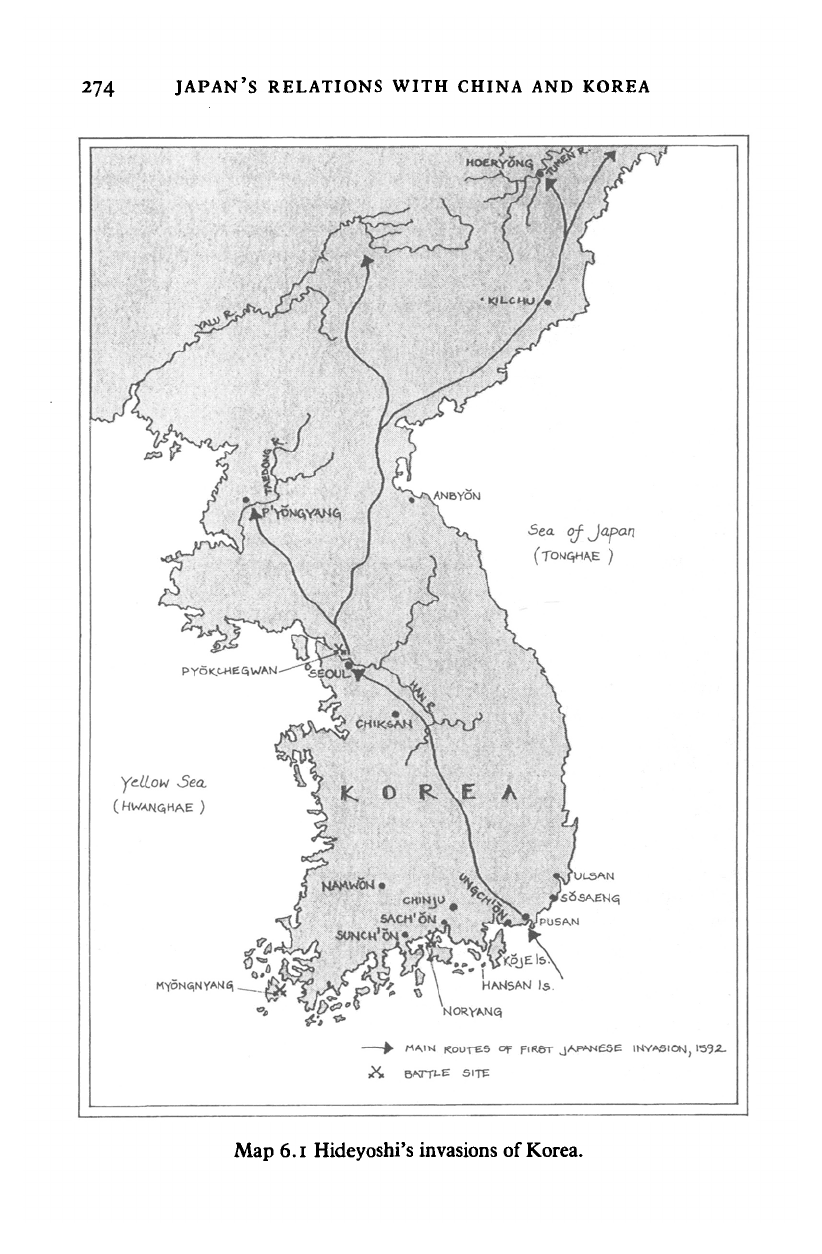

The invasion began on Tensho 20.4.12 (May 23, 1592) when the

first division of the Japanese expeditionary force landed in Pusan. This

division was composed of the contingents of Dom Agostinho Konishi

(Yukinaga, daimyo of Uto in Higo, I556?-I6OO), Dom Dario So

(Yoshitoshi, daimyo of Tsushima, 1568-1615), Dom Sancho Omura

(Yoshiaki, daimyo of Omura in Hizen, 1568-1616), Dom Protasio

Arima, Matsuura Shigenobu (daimyo of Hirado in Hizen, 1549-

1614),

and Goto Sumiharu. The prominent presence of "Christian

daimyo" - not really odd, as they were concentrated in western

Japan - gives at least this stage of the undertaking the air of

a

bizarre

crusade. The Japanese again demanded free passage through Korea;

the Koreans refused, choosing resistance over dishonor; and the hos-

tilities commenced. Pusan fell the next day. (See Map 6.1.)

From Pusan, the Japanese forces advanced with startling speed

northward up the peninsula. They were barely impeded by the totally

unprepared Korean army. Many Korean commanders abandoned

their posts, and others were overwhelmed by the Japanese, whose

musketry inspired terror in the defenders. Eighteen days after the

Japanese landing at Pusan, the king of Korea fled his capital, Seoul,

for P'yongyang. A mere three weeks from the start of

the

invasion, on

5.3 (June 12), Seoul fell to the force led by Konishi and to the division

made up of the units of Kato Kiyomasa (daimyo of Kumamoto, 1562-

1611),

Nabeshima Naoshige, and Sagara Nagatsune (daimyo of Hito-

yoshi in Higo, 1574-1636). By 6.15 (July 23), Konishi's force had

occupied P'yongyang, again causing the king of Korea to flee. It was

destined, however, to get no farther than P'yongyang, remaining there

until the beginning of

1593,

when it was defeated and forced to with-

draw by a Chinese army sent to the relief of Korea. In the meantime,

the second division of Japanese troops, which had advanced jointly

with Konishi's force from Seoul, split off from it at Ansong in

Hwanghae Province and proceeded to the northeast. Its exploits there

deserve our attention, as they illustrate nicely the policies and predica-

ments of the Japanese occupation army in Korea.

Having departed Ansong on 1592.6.10, the army of some twenty

59 See Miki Seiichird, "Chosen no eki ni okeru gun'yaku taikei ni tsuite" (1966), in Fujiki

Hisashi and Kitajima Manji, eds., Shokuho seiken, vol. 6 of Ronshu Nihon rekishi (Tokyo:

Yuseido, 1974), pp. 306-23; and cf. Fujiki Hisashi, Oda-Toyotomi

seiken,

vol. 15 of Nihon no

rekishi

(Tokyo: Shogakkan, 1975), pp. 325-7, 341-9.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

274 JAPAN'S RELATIONS WITH CHINA AND KOREA

MMM RourE5 OF FIRST

SITE

j I5g.2_

Map 6.1 Hideyoshi's invasions of Korea.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008