The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 4: Early Modern Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

AN ERA OF URBAN GROWTH 535

plaints about allegedly exorbitant and unfair prices, hold conciliation

talks in commercial disputes, and investigate suspicious deaths. For

this,

the representatives were paid a salary of a little less than

five

koku

of

rice

each, about one-half of what the city elders received.

The groups of ten households

(juningumi)

constituted the final link

in the administrative chain. The groups had a long history in Kana-

zawa, and the term can be found in early-seventeenth-century docu-

ments. Apparently not all urban commoners formed themselves into

such groups, however, until domain proclamations issued in the 1640s

instructed them to do so. These groups of ten households (in reality,

the number of households in any one group often exceeded that num-

ber) were the functional equivalent of the household groups estab-

lished in the rural villages in most domains.

In one sense, the groups preserved the interests of the merchant and

artisan neighborhoods, since they functioned as units of mutual aid

and self-help. In Kanazawa, for instance, members were supposed to

assist neighbors who fell on hard times

financially,

and from the mid-

seventeenth century each group maintained firefighting equipment

such as ladders, rakes, and rain barrels. Looked at from another per-

spective, the groups reflected an effort by the daimyo to extend his

authority and laws over the commoner populace, as the group mem-

bers were held jointly responsible for obeying the law and, in theory,

could be collectively punished for the actions of any single member.

Beyond this, the groups also carried out a variety of administrative

functions. They assembled periodically to hear a reading of legal

codes,

enforced the provisions of wills and decided the disposition of

property when a member died without leaving such a document, and

verified that any member who moved to a new ward left no debts

behind. Moreover, they conducted conciliation talks whenever quar-

rels,

commercial disagreements, or land disputes among group mem-

bers interrupted neighborhood tranquility. If no satisfactory solution

could be found, then the ward representative, and ultimately the city

elder if

necessary,

would be called in for further rounds of negotiation.

Only if the mediation at all these levels failed did the dispute move up

the ladder for settlement by samurai officialdom.

In pace with the amplification of the urban administrative apparatus

during the first half of the seventeenth century, Kaga's officials acted

to establish a written, legal basis for their political authority by issuing

codifications of

laws

and ordinances. These were promulgated accord-

ing to status group, with different codes for the samurai and for the

urban commoners. During the early years of

the

castle town's growth,

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

536 COMMERCIAL CHANGE AND URBAN GROWTH

the Maeda daimyo issued three separate codes regulating the samurai

life:

in 1601,1605, and 1612 (with a set of supplements in 1613). Here,

daimyo law was very limited in scope and intent. For instance, the

1605 code, issued under the personal seal of Maeda Toshinaga (1562-

1614),

prohibited the following:

1.

Walking on the streets at night.

2.

Loitering on the streets.

3.

Singing on the streets.

4.

Playing the flute

(shakuhachi).

5.

Holding sumo matches on the street.

6. Dancing in the streets.

7.

Masking one's face with a

scarf.

Clearly, the government's chief concern was to preserve law and order

and to establish procedures for the adjudication of disputes. The other

samurai codes played on the same themes: They forbade cliques, de-

clared that retainers should not harbor thieves or suspected criminals

among their rear vassals, specified that all parties involved in violent

quarrels were to be judged equally guilty, irrespective of who was at

fault, and prohibited gambling, with specific rewards for anyone who

supplied information about violators.

The laws directed at the merchants and artisans were much more

numerous, and major codifications were issued in 1642 and 1660. A

concern with peace on the city streets could also be detected in these

documents. The 1642 code, for instance, carried prohibitions against

gambling, gossiping, and keeping dogs as pets; whereas the 1660 edi-

tion repeated earlier injunctions against prostitution, wearing swords,

and urinating from the second floor of houses.

But these merchant codes could intrude more into the lives of the

urban commoners than did the samurai codes. Particularly noticeable

was the expansion of government involvement in the economic life of

the townspeople. The 1660 code stipulated that maximum interest

rates be fixed at 1.7 percent per month and prohibited any joint

samurai-merchant business ventures. Yet another article announced

that a representative from the City Office would visit any person who

fell behind in his debt repayments or credit obligations, an especially

important clause for the merchants and artisans of Kanazawa, as it

promised government assistance in collecting all debts. Another fea-

ture of merchant codes was a concern with public services. The 1660

code contained clauses concerning garbage disposal, the firefighting

responsibilities of the household groups, and the duties of the ward

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

AN ERA OF URBAN GROWTH 537

patrols

(teishubari),

whose chief responsibility, which rotated among

the residents of each ward, was to patrol nightly the ward's streets,

watching for fire and criminal activity.

In addition to the major legal codifications, the domain government

issued a mass of ordinances during the middle of seventeenth century

that attempted both to regulate behavior and to further refine status

distinctions. An important ordinance in

1661,

for example, attempted

to synchronize clothing with status. Regulations that took effect on

New Year's Day of that year established the types of clothing fabrics

permitted to peasants, townspeople, and each major subdivision of the

samurai status group. Accordingly, high-level retainers such as mem-

bers of the Eight Houses and the commanders could wear thirteen

kinds of high-quality

silk;

retainers from the middle ranks were permit-

ted four kinds of lesser silk; and those such as the more minor archers

and riflers were restricted to pongee, cotton, and the rougher fibers of

flax, hemp, and vines, known collectively under the rubric of

nuno.

The regulations provided that townspeople could wear plain silk

(kinu)

and pongee, whereas the peasants were held to pongee and the rougher

fibers.

The domain complemented these clothing regulations with other

status decrees. Some laws set limits on the amounts and kinds of foods

that could be served on holidays and ceremonial days, with the samu-

rai permitted more opulent indulgences than merchants were. Accord-

ing to other laws, townspeople were not supposed to have carved

wooden beams or doors made from cedar in their homes, because

these were perquisites of the samurai class. Nor could townspeople,

unless they were seriously ill or over sixty years of

age,

ride in palan-

quins,

whose use was normally restricted to high-ranking samurai and

certain city officials.

The establishment of patterns of urban governance in early modern

Japan paralleled the transformations in the exercise of political author-

ity in rural areas and on the domain level, as explained in Chapters 5

and 9 of this volume. The daimyo of the late sixteenth century had

been personal autocrats who led armies, enfeoffed retainers, issued

decrees, and set policy. By the second half of the seventeenth century,

most of their successors had withdrawn from the direct, day-to-day

management of the affairs of government and, instead, had become

more nominal rulers whose chief function was to serve as the legitimiz-

ing agent of the administrative structure.

The retreat of the daimyo as personal leaders, however, did not

portend a decline in state powers, for the new bureaucracies of the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

538 COMMERCIAL CHANGE AND URBAN GROWTH

seventeenth century had more ability to tax, legislate, and punish than

did the daimyo of the previous

age.

Yet, in a profound historical twist,

the exercise of this power was also newly tempered; first, by the

government's need to harmonize its policies with the aspirations and

wishes of the merchants and artisans in the cities and, second, by the

obligation of government to subordinate its impulses to the require-

ments imposed by the new bureaucratic practices, legal codes, and

standardized procedures that grew up during Japan's transition from

the medieval to the early modern polity. The history of cities such as

Kanazawa demonstrate how castle towns brought together the concen-

trations of wealth and power that made possible this shift away from

personal forms of authority toward a new style of bureaucratic statism.

CITIES AND COMMERCE IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

Castle towns and the agricultural revolution

The commercial economy grew significantly during the period of Ja-

pan's political unification, from the middle sixteenth down to the end

of the seventeenth century. The point of departure for this expansion

was a revolution in agricultural production. Although the statistical

data are not without shortcomings, some scholars have estimated that

the amount of cultivated paddy more than doubled in the century

from 1550 to 1650 alone.

28

Productivity and yields also increased as

better fertilizers, improved farm tools, and new strains of seeds made

their appearance. Important as well were reclamation and large-scale

irrigation projects, many underwritten by daimyo who hoped to ex-

pand the taxable revenue base of their domains. Another (actor was

the role played by the individual peasant household. As ruran?esidents

acquired more secure rights to their holdings, a process discussed in

Chapters 3 and 10 in this volume, the farmers came to believe that

significant portions of any increase in yield would accrue to them, and

thus they were more willing to make the investments necessary to

boost productivity and to bring formerly marginal fields into cultiva-

tion.

29

Indeed, signs of a growing rural prosperity - new and larger

houses, improved diet, better clothing - were evident in most areas of

Japan by the middle of the seventeenth century.

These improvements in the nation's productive capacity touched off

28 Kozo Yamamura, "Returns

on

Unification: Economic Growth

in

Japan, 1550-1650,"

in

Hall,

Nagahara,

and

Yamamura,

eds.,

Japan

Before

Tokugawa,

p. 334.

29 Ibid.,

pp.

339-57-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY 539

a dynamic spurt in population growth. Although accurate statistics

were not kept at that time, some demographers and historians place

the growth rate in the range of 0.78 to 1.34 percent annually between

1550 and 1700. Others posit an accelerating rate during the seven-

teenth century, rising from 0.5 percent in the early decades of the

century to nearly 1.4 percent between 1650 and 1670.

3

° Despite these

differences of opinion, most scholars agree that the greatest population

increases took place in the last half of the seventeenth century and

that, in aggregate, the country's total population grew from roughly 12

million persons to approximately 26 million to

30

million at the time of

the shogun's census in 1721.

The rapid increase in both productive capacity and population also

brought about changes in household composition. The number of

individual farm households increased at a faster rate than did overall

production growth, and this statistic indicates a rearrangement of

household configuration away from a complex, extended family to-

ward smaller nuclear families, many of which were created as branches

and given land by the stem family. The disappearance of the extended

farm family meant that the small independent cultivator

(jisakushono)

who farmed his holding with the labor of his own family became the

most common type of peasant household. As the process of subdivi-

sion continued, however, there eventually came into being a growing

number of families who possessed land that was barely sufficient for

their needs. Indeed, by the 1670s the shogunate had become so con-

cerned about the destabilizing aspects of the further subdivision of

farmland that it issued a "law restricting the division of farmland"

{bunchi

seigen-rei).

1

'

The evolution of the farm family also brought about conditions that

favored urban migration. As families shed surplus members during

the first half of the seventeenth century, there were always some who

did not have enough land to establish branch families. These disfran-

chised men and women often moved into the growing castle towns,

where they could hope to find work as day laborers or unskilled arti-

sans,

although the poorest of the women were sometimes forced into

prostitution. Similarly, those new branches who had received only

marginal amounts of land were in a position of continuous economic

30 Hayami Akira, Kinsei

ndson

no

rekishi

jinkogaku-teki

kenkyu

(Tokyo: Toyo keizai shimposha,

1973),

p. 23; and Shakai kogaku kenkyujo, ed., Nihon relto ni

okeru

jinko bumpu no choki

jikeiretsu

bunseki

(Tokyo: Shakai kogaku kenkyujo, 1974), pp. 42-57.

31 The fullest discussion of the relationship between the commercialization of agriculture and

household composition remains Thomas C. Smith, The Agrarian Origins of Modem Japan

(Stanford,

Calif.:

Stanford University Press, 1959).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

540 COMMERCIAL CHANGE AND URBAN GROWTH

jeopardy, and in years of even slight drought or cold weather they

might have to abandon their homes to search for work, or even to beg,

in the castle towns.

There is no way of knowing the exact magnitude of migration in the

seventeenth century, but given the rapid growth of the castle towns,

surely several hundreds of thousands of persons were on the move in

the middle decades of the century. In Kanazawa alone, to take one

example, between 1660 to 1663, arriving would-be merchants and

artisans leased well over 300,000 square meters of farmland on the

fringes of the city.

32

Regardless of the exact scale of migration, how-

ever, local officials were clearly worried, and many castle towns en-

acted special ordinances in the middle of the seventeenth century that

discouraged further movement into their cities and that attempted to

bring beggars under closer supervision.

33

The ongoing migration from village to city also prompted the sho-

gunate to introduce the system of family census registers

(koseki)

as

one way of gaining some measure of control over this migrant popula-

tion. Before this, the shogunate had compelled each temple to conduct

a religious investigation

(shushi aratame)

as a means of suppressing

Christianity. It had also ordered a census and household count in each

village for the purpose of making corvee levies, and at the same time,

it instructed peasants to report the number of cattle and horses they

were raising. In 1670, however, these two records were combined in

the religious and census investigation (shumon

aratame).

This new

reporting system began the practice of requiring all the households of

each domain, without exception, to register the names of their mem-

bers with ward or village officials and to identify their temple of

affiliation. Once a person was registered, if he wanted to migrate, he

had to prove that he had obtained the permission of

his

temple and his

ward or village.

In addition to provoking the imposition of stricter political controls,

the large influx of population into the cities in the middle decades of

the seventeenth century affected the physical layout of the castle

towns. First, the castle towns started to expand into areas beyond the

geographic limits that the daimyo founders had envisioned. The mi-

grants, mostly poor, tended to live where rents were lowest, on the

rural fringes of the castle towns. Increasingly, the boundaries between

urban wards and agricultural villages became blurred as men and

32 Tanaka Yoshio, "Kinsei jokamachi hatten no ichi kosatsu - 'Aitaiukechi' kara mita joka-

machi, Kanazawa no baai,"

Hokunku shigaku

8 (1959): 19-37.

33 For a specific example, see McClain, Kanazawa, pp. 124-32.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY 541

women who worked as laborers, craftsmen, or bushi household ser-

vants rented lodgings in settlements that were under the administra-

tive jurisdiction of the rural magistrates

(Jkori

bugyo). Moreover,

theaters and houses of prostitution often sprouted up in these fringe

areas.

This growth caused, in turn, a whole new set of problems, as

farmers complained about the newcomers trampling over fields, break-

ing down dikes, or otherwise disrupting the rhythm of agricultural

life.

Many urban governments responded by transferring these areas

to the jurisdiction of the city magistrates, thus making the merchant-

farmer wards part of the cityscape.

The physical expansion of the cities played havoc with older notions

of urban planning. Originally, for instance, most daimyo had pre-

ferred, for defensive purposes, to situate their foot soldiers and the

large Buddhist temples in a concentric circle around the outer limits of

the city. Now many had to abandon that design or else undertake

considerable expense and trouble to relocate the warrior residences

and religious institutions. Predictably, this kind of urban reorganiza-

tion most frequently occurred in cities that had the misfortune of

suffering a major fire. Such conflagrations provided a convenient pre-

text for the daimyo to relocate people who otherwise would have been

reluctant to move to strange neighborhoods, away from old friends

and familiar shops and places of

worship.

Following such fires, many

daimyo also widened the streets and established open areas as fire-

breaks at strategic points.

Concurrently, the principle that persons of the same occupation

ought to live together in the same wards suffered serious erosion, and

except for some special occupations such as that of gunsmith or

swordsmith, artisans as well as merchants began to reside in scattered

locations throughout the expanding cities. One reason contributing to

this process was that some established merchants and artisans voluntar-

ily moved into the newly created fringe wards, in search of new cus-

tomers or lower shop rents. A second reason was that the forced

relocation of some bushi turned the fringe areas into real residential

hodgepodges, adding samurai to the merchant, artisan, and day la-

borer populations. In Kanazawa, for instance, seven of the households

in one ward on the outskirts of the city belonged to artisans, twenty-

eight to merchants, six to day laborers, and thirteen to samurai.

34

The complexion of the inner city changed as well. As some of the

34 For this and other examples, see Tanaka, Jokamachi Kanazawa, pp. 103-106; and Tanaka

Yoshio, Kaga

hart

ni

okeru toshi

no

kenkyu

(Tokyo: Bun'ichi sogo shuppan, 1978), pp. 140-5.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

542 COMMERCIAL CHANGE

AND

URBAN GROWTH

newcomers prospered, they moved into

the

older, more prestigious

sections

of the

city, usually choosing sites that suited their fancy

and

commercial needs, rather than adhering

to the

artificial occupation

divisions

of an

earlier age. Finally, many were tempted

by the

empty

land within

the new

firebreaks.

Not

uncommonly, poorer merchants

and artisans squatted

on

this land, much

to the

chagrin

of

those

do-

main authorities who were still wedded

to the

notion

of

a

planned city.

But

the

perseverance

of the

homesteaders

to

stay

was

usually greater

than

the

resolve

of

the city authorities

to

evict them.

The expansion

of

cities

in

the middle

and

later decades

of

the seven-

teenth century was only

one

factor working to change the character and

function of

cities.

By the end of the century, the commoners of the castle

towns

had

also achieved new levels of economic prosperity and brought

into being

a

distinctive urban-based culture.

The

interaction

of the

population migration with

the

commercial

and

cultural developoment

inside the city created

a new

kind of castle town,

as we

shall

see,

one that

was very different from

the

expectations

of the

daimyo during

the

period

of

urban creation

at the

beginning

of

the century.

Commercial development

and

castle

town merchants

Paralleling

the

agricultural revolution

was a

spectacular expansion

in

the volume

of

commercial exchange that began during

the

middle

decades

of the

sixteenth century

and

continued until

the end of the

seventeenth century. Historians have identified several causes that

contributed

to

this process, including

the

policies implemented

by the

daimyo during

the

late Sengoku period

in

order

to

strength^

the

economic basis

of

their rule, such

as the

abolition

of

toll gate barriers

and

the

promotion

of

periodic markets that would

be

open

to all

traders.

35

Daimyo of the seventeenth century continued these policies

and

also

vigorously promoted

the

expansion

of

permanent markets within

the

new castle towns, such

as

when

the

Maeda daimyo

set

aside two plots

of land

in the

commercial heart

of

Kanazawa

to be

used

by

fish

and

vegetable dealers.

36

Other significant stimulants included the standard-

35 The classic work on this topic is Sasaki Gin'ya,

Chusei shohin ryutsu

no

kenkyu (Tokyo: Hosei

daigaku shuppankyoku, 1972). In English, see Gin'ya Sasaki, with William B. Hauser,

"Sengoku Daimyo Rule and Commerce," in Hall, Nagahara, and Yamamura, eds., Japan

Before Tokugawa, pp. 125-48; and Kozo Yamamura, "Returns on Unification," on pp. 327-

72 of the same volume.

36 Kanazawa-shi Omicho ichiba-shi hensan iinkai, ed., Kanazawa-shi

Omicho ichiba-shi

(Kana-

zawa: Hokkoku shuppansha, 1979), pp.

10-25.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

543

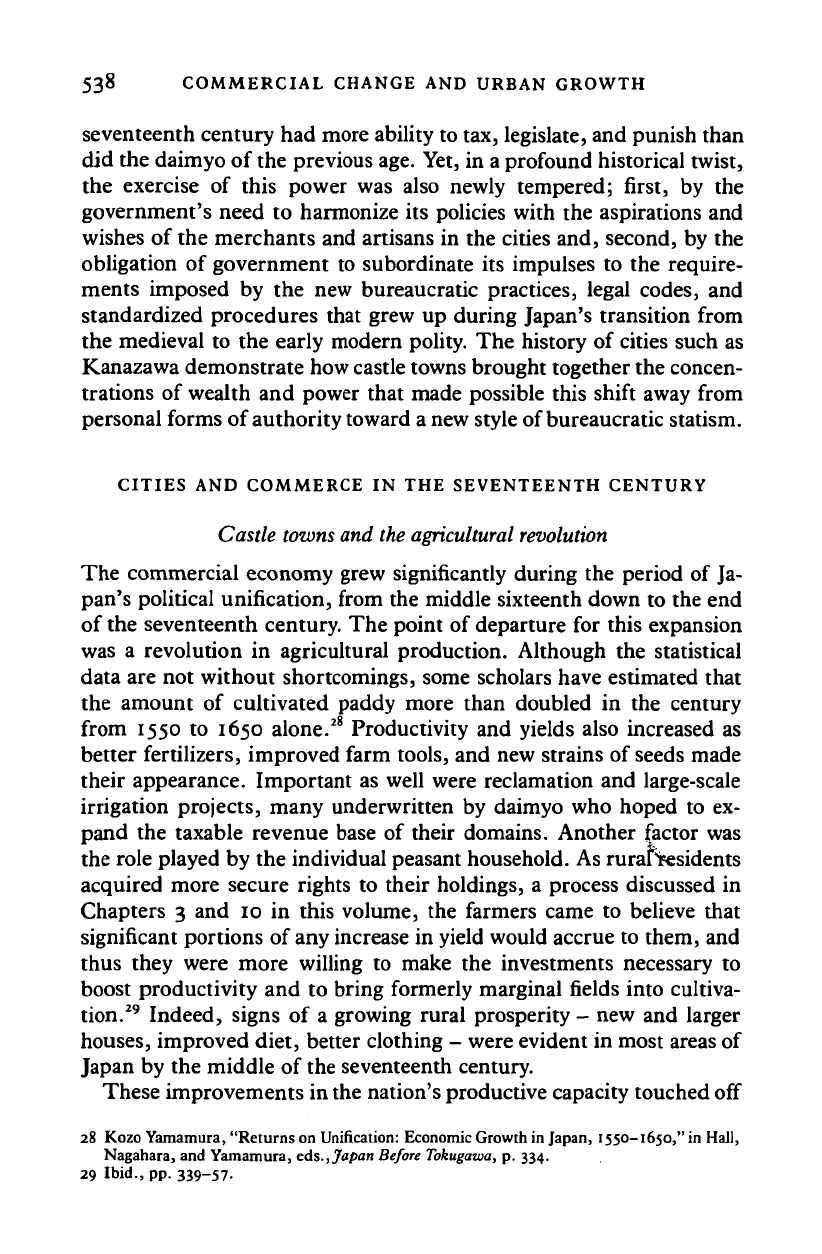

EDO

BI 100,000 °K.

NIORJ;

•"

"

® 50,000

-TO

90,000

0

• 30,000 -ro 50,000 „

Map

11.1

Major cities and transportation

routes,

eighteenth century.

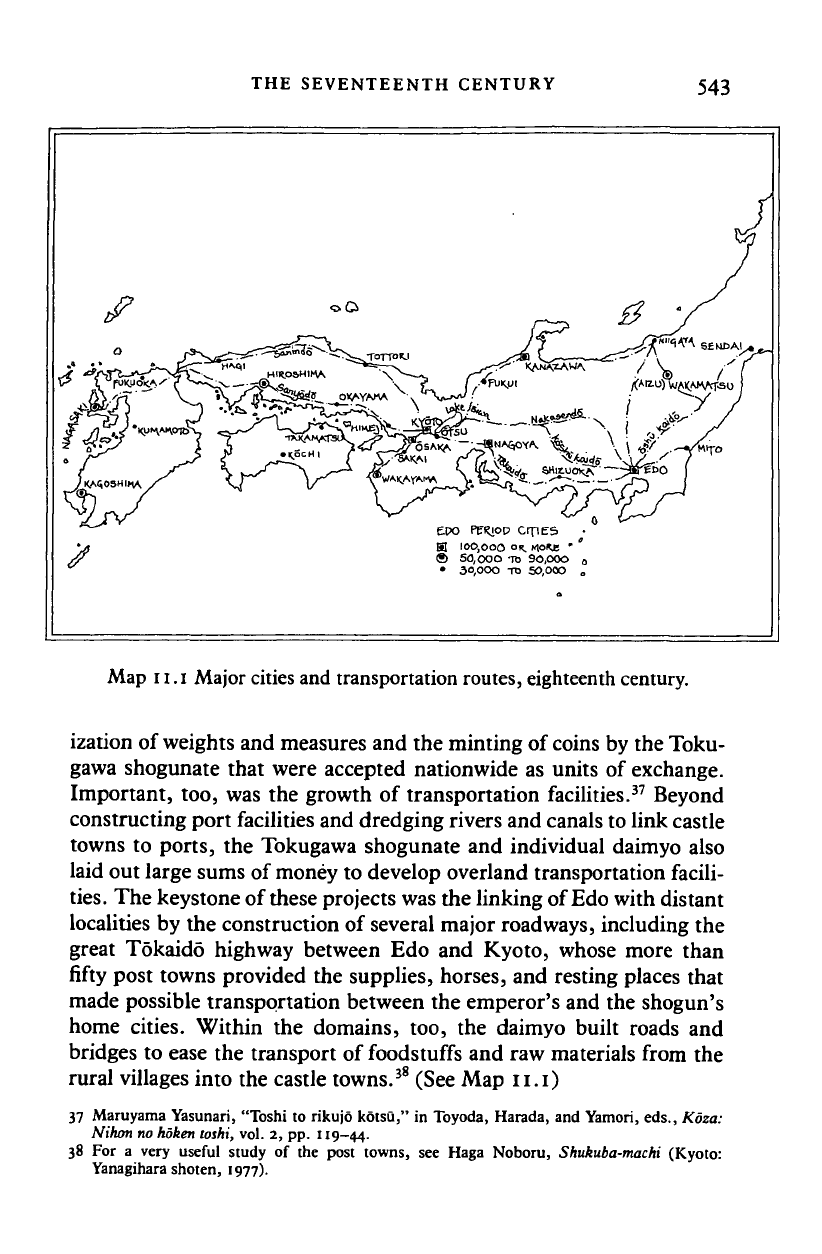

ization of weights and measures and the minting of

coins

by the Toku-

gawa shogunate that were accepted nationwide as units of exchange.

Important, too, was the growth of transportation facilities.

37

Beyond

constructing port facilities and dredging rivers and canals to link castle

towns to ports, the Tokugawa shogunate and individual daimyo also

laid out large sums of money to develop overland transportation facili-

ties.

The keystone of these projects was the linking of Edo with distant

localities by the construction of several major roadways, including the

great Tokaido highway between Edo and Kyoto, whose more than

fifty post towns provided the supplies, horses, and resting places that

made possible transportation between the emperor's and the shogun's

home cities. Within the domains, too, the daimyo built roads and

bridges to ease the transport of foodstuffs and raw materials from the

rural villages into the castle towns.

38

(See Map n.i)

37 Maruyama Yasunari, "Toshi to rikujo kotsu," in Toyoda, Harada, and Yamori, eds., Koza:

Nihon no

hdken

toshi, vol. 2, pp. 119-44.

38 For a very useful study of the post towns, see Haga Noboru, Shukuba-machi (Kyoto:

Yanagihara shoten, 1977).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

544 COMMERCIAL CHANGE AND URBAN GROWTH

Another factor was the institutionalization of

the

system of alternate

residence. Although the custom of personal attendance on one's supe-

rior and the submission of hostages as an expression of loyalty had

become fairly common during the sixteenth century, these practices

were made a permanent obligation for the daimyo only after 1633.

From that date, daimyo were compelled to alternate their residences

between Edo and their home domains, to build elaborate mansions in

Edo,

and to leave appropriate retinues, including their wives and

children, permanently in the shogun's city. This system was designed

to permit the shogunate to maintain a close surveillance over the

daimyo, but it also had the consequence of stimulating the nation's

volume of commercial exchange as the daimyo processions moved

back and forth along the new highways that crossed Japan.

39

The growing wave of commercial transactions had several important

consequences. Agricultural patterns changed enormously, for now

farmers were able to concentrate more profitably their energies on

growing commercial crops, such as cotton, tea, hemp, mulberry, in-

digo,

vegetables, and tobacco, for sale to the urban markets.

40

Re-

gional specialization also became a feature of economic life, as great

numbers of villagers around Osaka, for instance, started to switch over

to cotton cultivation while farmers in northern Japan began to raise

horses and cattle for sale as draft animals.

41

Individual rural house-

holds began to develop by-employments or simple rural industries, so

that even within a single domain certain villages became known for

their production of goods such as paper, charcoal, ink, pottery, lacquer

ware, or spun cloth.

Concurrent with the commercial growth of Tokugawa Japan was the

daimyo's increasing need for cash revenues, which could come only

through participation in interregional trade. One part of the story is

simply that the daimyo needed money to buy the growing number of

specialized goods that were produced outside their own domains. But

the system of alternate residence also put a strain on the daimyo's

finances. The experience of the Maedo daimyo of Kaga was fairly

typical. By the end of the seventeenth century, their journeys to Edo

39 The most complete treatment of the alternate residence system in English is Toshio George

Tsukahira, Feudal Control in Tokugawa Japan: The Sankin Kotai System, Harvard East Asian

Monographs, no. 20 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1966).

40 This shift in cropping patterns is discussed in Watanabe Zenjiro, Toshi to noson no aida

(Tokyo: Ronsosha, 1983), esp. pp. 121-49, 241-76.

41 For examples of this sort of regional specialization in the Kinai, Morioka, and Okayama, see

Susan B. Hanley and Kozo Yamamura, Economic and

Demographic

Change in Preindustrial

Japan, 1600-1868 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1977), pp. 91-198.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008