Walbank F.W., Astin A.E., Frederiksen M.W., Ogilvie R.M. The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 7, Part 1: The Hellenistic World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

LYSIMACHUS AND ANTIGONUS GONATAS I I 7

At the beginning of

277,

as he was trying to gain a foothold in Thrace,

Gonatas encountered, in the area of Lysimacheia, a large band of Gauls

whom he succeeded in luring into an ambush and wiping out.

57

This feat

of arms (the only heavy defeat inflicted on the Celts in these years) had

the double effect of putting

a

stop to the Gaulish invasion in Europe and

opening the way to Macedonia to the victor. Gonatas could now present

himself in Macedonia not merely as a dubious pretender, the son of an

unpopular and dethroned king, but as a true

Soter.

We do not, indeed,

know anything of the manner of his return, but nevertheless in 276 he

was master of the country and of its Thessalian appendage.

58

So the pattern

of

the great Hellenistic kingdoms was finally fixed,

under

the

three dynasties

—

the

Ptolemaic,

the

Seleucid

and the

Antigonid

—

which were

to

preside over their destinies until their

respective ends. The great game

of

diplomacy and war, and also

of

economics, which was for so long to provide the life-force of this new

world, had already begun

in

Asia.

59

57

Just. xxv.

1.2—10;

2.1—7. Fora discussion

of

the date: Nachtergael

1977,

167

and n.

191: (E

I I 3).

58

The

date

of

Gonatas' seizure

of

power

in

Macedon,

the end

of

277

(Nachtergael

1977, 168,

n. 192:

(E 113))

does

not

coincide with

his

first regnal year, which

is 283

(Chambers

1954,

385ff.:

(D

6)).

59

See

below,

ch. 11.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER

5

PTOLEMAIC EGYPT

E. G.

TURNER

PRELIMINARY NOTE

ON

THE PAPYRUS SOURCES

This note

is

intended to issue two warnings. The first is that the historian

of Ptolemaic Egypt cannot call at will on written sources contemporary

with the period he is describing. From the time of Ptolemy I Soter at the

moment of writing this note (January 1980) I know of only two certainly

dated Greek papyri, and some six scraps, to which should be added some

thirty private documents

in

demotic Egyptian.

The

first

ten

years

of

Ptolemy

II

are also blank. A trickle of texts commences in the late 270s

B.C.; from about 259 B.C. it becomes a flood which lasts down to about

215 B.C. Thereafter there is comparative poverty till the middle

of

the

second century.

The

end

of

this century

is

well documented

for the

Fayyum villages, and there exist

a few

papyri

of

the first century B.C.

Chronological continuity is assured by the Greek and Demotic ostraca

(normally stereotyped tax receipts), not by papyri. Yet only part of the

stage which

is

Egypt

is

thus flood-lit: above

all

the Fayyum,

the

area

most recently won from the desert, the first

to

revert

to

desert and

in

consequence

to

conserve its archives over twenty-three centuries.

But

no documents survive from the Delta, the richest and most populous

area

of

Egypt; from Alexandria only such texts

as

were fortuitously

carried up-country.

In

Middle Egypt Memphis (through its necropolis

at Saqqara), el-Hiba, Heracleopolis, Hermopolis, Oxyrhynchus, Lyco-

polis intermittently offer finds containing thinly spread and discontinu-

ous information. The Thebaid moves

in

and out

of

the gloom,

for

the

most part shrouded

in

darkness, except for its tax receipts on potsherd.

Papyrologists

and

historians

of the

last

two

generations have been

dazzled

by the

bright lighting

and too

ready

to

extrapolate

and

generalize from their new information.

It is

only one

of

many great

services

to

scholarship of Claire Preaux that she first called attention

to

this discontinuity in time and place of the evidence, and warned against

the supposition that any pattern that may be identifiable under full flood-

lighting continues into

the

unilluminated areas.

1

On

herself and

her

1

Two examples in minor matters:

a

cavalry-man's holding in the Memphite nome is

120

arouras,

in the Arsinoite 100 arouras.

In

the Arsinoite nome fishermen receive a state wage; in the Thebaid

they have no wage but hand over a quarter

of

their catch.

A

major example (to be discussed

on

pp.

143—4)

is

provided

by

the competence

of

the

dioiketes

Apollonius.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PTOLEMY

I I 19

pupils she imposed the discipline of noting date and provenance of texts

offered in evidence, and her judgement has repeatedly been proved sage.

The second warning is against the supposition that the bulk of the

papyrus evidence is now published and generally available to scholars. It

has several times been asserted recently (i.e. in 1978 and 1979) that the

major finds of Greek papyri of the Ptolemaic period are published. But

the reader should bear in mind the body of petitions acquired by the

Sorbonne in 1978

(enteuxeis

which link with the texts from Ghoran and

Magdola already known), the mass of cartonage in Lille or the imposing

array of undismounted mummy masks in Oxford, the possible return

from which is unknown. Moreover work on demotic texts is only just

beginning to get into its stride. One reason why this chapter differs

radically from the one it replaces (written fifty years ago by a scholar of

wide sympathies and voracious reading) is the progress made by

demotic studies during the interval. There are now vigorous centres of

demotic in England, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, France, Italy

and the United States of America (a list which is not exhaustive). Two

major finds of demotic material made by W.

B.

Emery, H. S. Smith and

G. T. Martin at Saqqara in 1966—7 and

1971—

2,

mainly of the fourth

and third centuries B.C., promise invaluable Memphite background

material for the subject of this chapter;

2

a deposit found by the French

School at Luxor in 1970 and 1971 promises equally well for Thebes in

the third century B.C. The dream oracles from Saqqara contribute to

knowledge of the opening years of Ptolemy VI. The demotic book of

law practice from Hermopolis is now at last in scholars' hands. A regular

rhythm of future publication is to be looked for.

The statement of

a

distinguished Egyptologist

is

especially appropriate

to this study: 'nothing can be gained by relying on unwarranted

assertions in the books of our predecessors; only patient collecting of

facts may in future replace mere guesses by more exact knowledge'.

3

Since 1927 great progress has been made in the collection of'facts' from

Greek papyri about the Ptolemies (in the

Prosopograpbia

Ptolemaica,

for

instance, or F. Uebel's monumental lists of cleruchs). But the analysis of

these 'facts' is still only in the preliminary stage.

I.

PTOLEMY

I

On the death of Alexander the Great on

1 3

June 323 B.C. Ptolemy, son of

Lagus and Arsinoe, obtained from Perdiccas, the holder of Alexander's

seal, the right to administer Egypt. He lost no time in taking possession

2

Exciting preview in Smith 1974: (F 148).

3

Cerny 1954.

2

9

:

(

F 2

3°).

on tne

subject of consanguineous marriage (below p. 137 n. 40).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

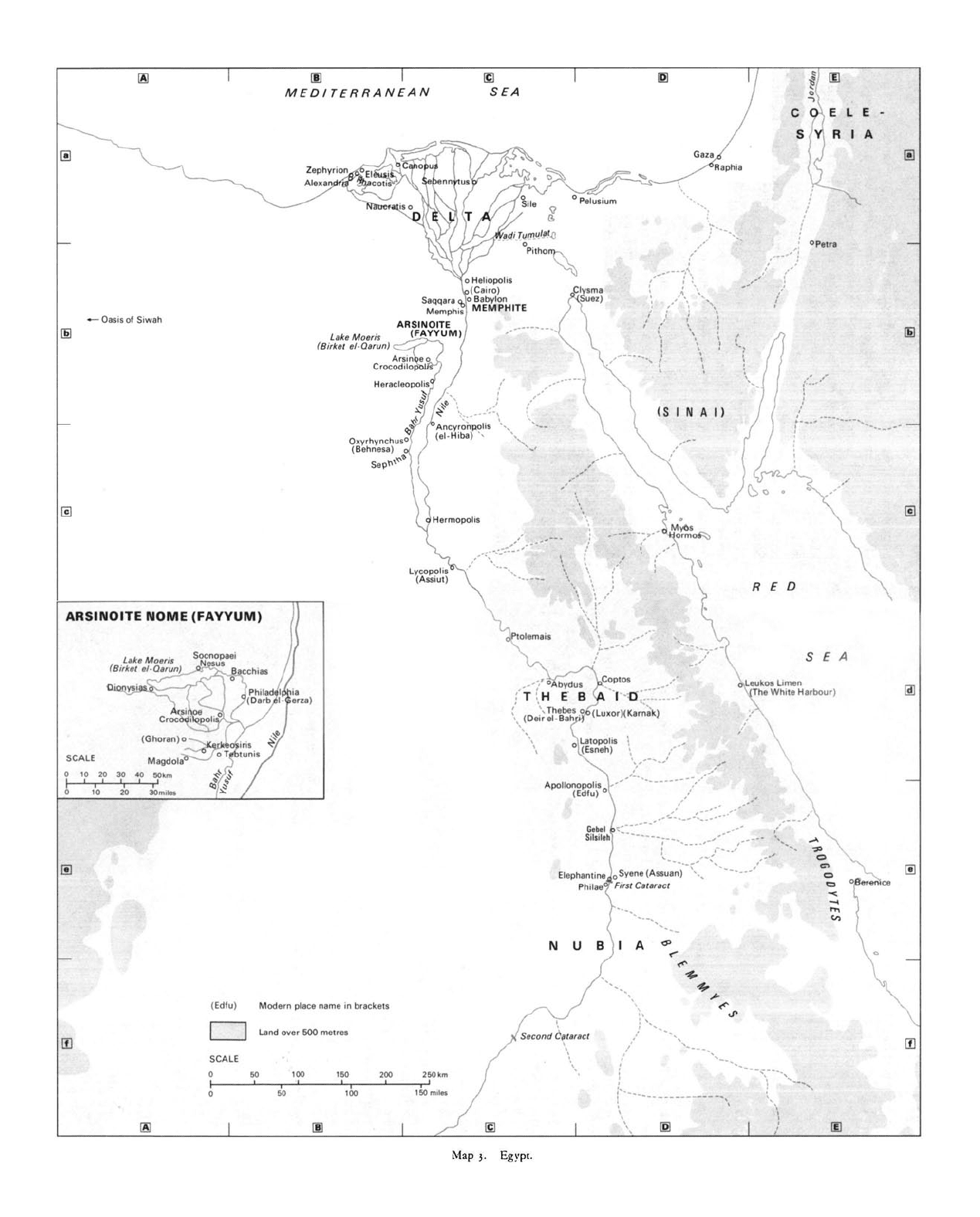

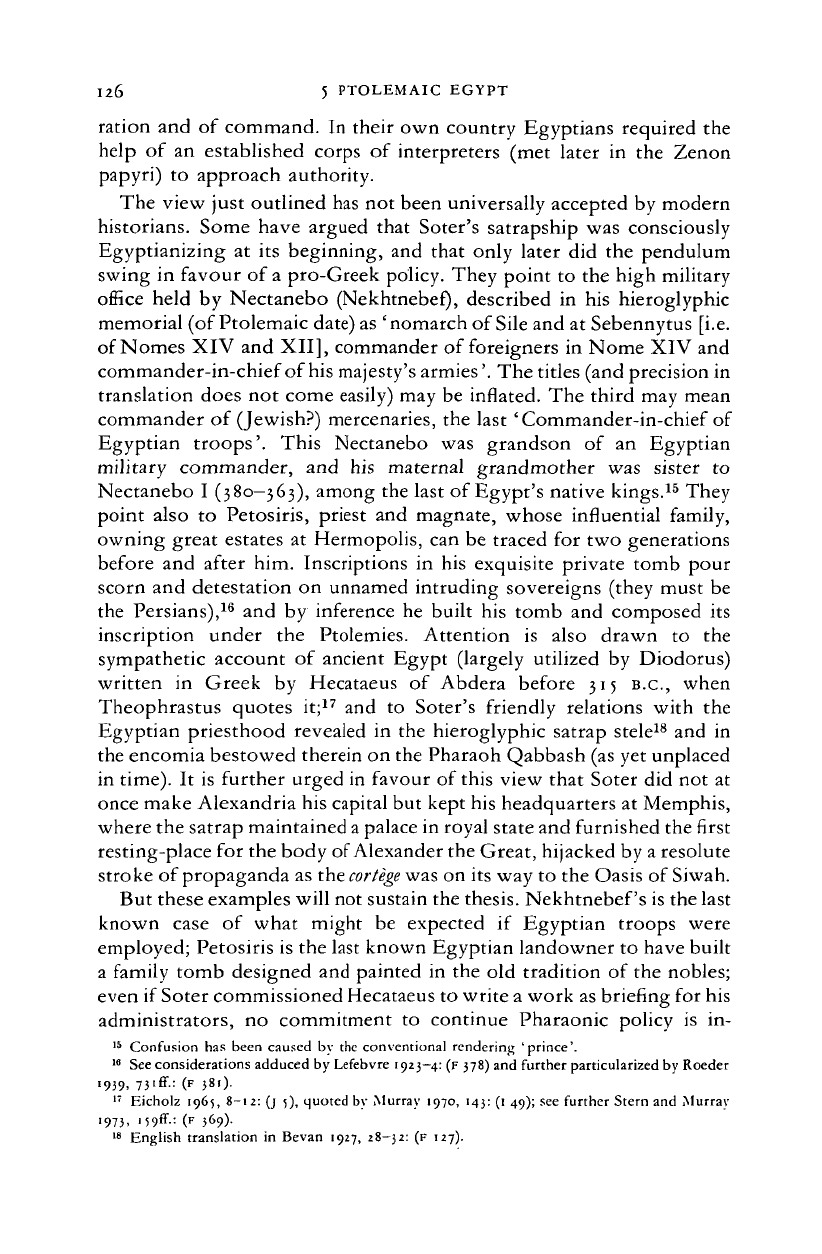

Map

3.

Egypt.

MEDITERRANEAN SEA

C

O E L E -

S /YI

R

I A

Gaza/

/•"Raphia

opetra

(SINAI)

,1

Myfts

Hormos

RED

SEA

o Leukos Limen

JThe White Harbour)

; T

!H

E

B

SA

10;:

^Ptolemais

Lycopolis^"

(Assiut)

(cj Hermopolis

"Ancyronpolis

(el-Hiba)

^

7

Oxyrhynchus

0

!

(Behnesa)

a

*— Oasis

of

Siwah

Xlysma

^Suez)

° Pelusium

Sebennytus

o

ksmmm

Alexa

n

<*

f

t^'5g3cot is^i

fed;

TumWC

"o

Pithonv,

^(o Heliopolis

\p(Cairo)

Saqqara

oJ°

Babylon

Memphis'! MEMPHITE

ARSINOITE

)

Lake Moans

J**™

M

>

(Birket ei-Qarun) crSr"'"')

(

Arsinoeoc

f

CrocodilopoJ/s*''/

/

HeracleopolisJ

/

ARSINOITE

NOME

(FAYYUM)

Lake Moeris ^^Jesus

36

'

\

(Birket

el-Qarun)_^r^^jte

c

h\

M

I j

V S I

^7(Darbel-ffierza)

A^irtpe~7a

( /

CrocOdilQpoliiA^.

/ I

(Gh0r8n)O

^Wo>ins

f

SCALE

Magdo..>--

/

°T"

,niS

/

0

1

0 2 0 3 0 4 0 50km

^/J /

1

' l' «/ /

0

10 20

30miles

/

(Edfu) Modern place name

in

brackets

Land over

500

metres

SCALE

0

50 100 150 200

250km

I

1

r—

1

H

1

H

0

50 100

150 miles

Second dataract

NUBIA

Elephantine

Jo

s

V

ene

(Assuan)

Philae

1

? First Cataract

Gebel

p

Silsileh

Apollonopolis

i

(Edfu)

°

n

Latopolis

"^(Esneh)

>

V

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

122 5 PTOLEMAIC EGYPT

of it as satrap

in

the name of Arrhidaeus, who had been proclaimed sole

king, pending

the

birth

of

Alexander's posthumous child (pp. 25—6).

It

is

worth spending some time

on the

rule

of

Ptolemy

I

(Soter,

as he

will here

be

called) since

the

first fifty years

of

Ptolemaic rule

in

Egypt

can

be

characterized only through the actions

of

the

ruler. For the study

of this period which witnessed

the

foundation

of

Ptolemaic govern-

ment, retrospective extrapolation from

the

better known Egypt

of

the

250s B.C. will falsify historical perspective.

And

history described

in

terms

of

personality

is not

inappropriate

to an age

when

men by

their

personal qualities effectively shaped events.

Soter

had

marched with Alexander

the

Great

to

Afghanistan

and

back,

and had

commanded

a

Division.

He was now

about forty-five

years old. Mentally

and

physically vigorous

(he

fathered

an

heir

at the

age

of

sixty),

he

was

a

man

of

action who successfully submitted

to the

discipline

of

intelligent diplomacy

and

policy,

and

refused

to be

discouraged by apparent failure. As brave and skilful captain, sage judge

of men

and

affairs, memoir-writer

and

hail-fellow-well-met,

he

knew

how

to

attract friends

of

both sexes

and to

hold their loyalty.

It

was

an

age when a man could not carve out a career

for

himself without carving

out careers

for his

friends. Success depended

on

attracting

men of

adequate calibre

for the

tasks that were also their opportunities,

on

rewarding

and

defending them,

and

continually consulting them about

innovations

of

policy.

The need

for

a springboard to satisfy his personal

ambition was what attracted Soter

to

Egypt.

No

deeper motive need

be

looked

for.

In

a

conference

of

the Successors

at

Triparadisus

(see p. 37)

Soter's

envoy maintained that Egypt was his by right

of

conquest,

it

was

'

spear-

won land'

{doriktetos

ge)^ From whom

had it

been conquered?

Not by

Soter from

the

Egyptians,

for

there

is no

mention anywhere

of

native

resistance to him. Just possibly there is an allusion to the conquest in

3 3 2

B.C.

by

Alexander

the

Great.

5

But to

make such

a

claim would hardly

distinguish Soter's case from that

of

his

rivals, since all the parties owed

their territories

to

Alexander's original conquests. Much more plausible

is a reference

to

Soter's repulse

of

Perdiccas

in

321 B.C.; possibly also

to

Soter's forceful take-over

of

Egypt from Cleomenes

of

Naucratis.

Cleomenes

had

held from Alexander himself

a

position

of

authority.

4

Diod. xvm.39.5

and

43.1

(in the

latter passage Perdiccas

is

specially mentioned).

5

Cf.

Diod. xix.85.3, where

doriktetos cbora

seems

to

apply

to the

whole territorial area

of

Alexander's conquests. Possibly Diodoms gives

two

different meanings

to the

term.

In the two

passages cited

in

n. 4

a

reference

to

Alexander cannot be the meaning. The word

doriktetos is

used

in

the context

of

a

claim

to

Egypt asserted

by

Soter against

his

fellow Diadochi.

It is

the reason why

Soter and not, e.g., Antigonus

or

Seleucus should hold Egypt.

In

any case the term has nothing

to

do with

an

assertion

to

legal title

of

ownership

of the

land

of

Egypt,

a

sort

of

manifesto

of

'nationalization'

of

the land,

as

claimed

by

Rostovtzeff 1953,

1.267:

(A

52).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PTOLEMY I I23

Since Egypt was a province of the Persian empire, his post is correctly

described as a satrapship by the ancient historians when they forsake

generalities; it is an unnecessary guess of

some

modern historians that he

was 'administrator'

(dioiketes).

He used his office to extract double dues

from the Egyptian priesthood, and to hold Aegean and mainland Greece

to economic ransom during a famine by means of

a

ruthless monopolis-

tic exploitation of exports of Egyptian corn. One of Soter's first acts was

to entrap him and put him to death.

'Soter', wrote Diodorus, probably drawing on the histories of

Hieronymus of

Cardia,

who himself played a part as diplomatist in these

troubled times, ' succeeded to

(parelabe)

Egypt without putting himself

at risk; towards the natives he behaved generously

(philanthropos),

but he

succeeded to

{parelabe)

8,000

talents, and began to recruit mercenaries

and collect military forces.'

6

A modern German historian

7

aptly quotes

this passage in support of his characterization of the antithesis between

generosity towards the natives and reliance on non-Egyptian soldiers as

the fundamental and permanent basis of Ptolemaic rule. The claim is too

sweeping, but it is appropriate to Soter's action in 323/2

B.C.

The term

translated' generously'

{philanthropos)

represents not merely the abstract

quality of generosity

(philanthropia)

which theory demanded in a king; it

refers to

his

philanthropa,

the acts of clemency traditionally incorporated

in a proclamation to his subjects in Egypt by a king on his accession.

8

Soter is informing his new subjects that one satrap has succeeded

another, and that the new one will not repeat the abuses of his

predecessor.

Diodorus' specific statement on Soter's recruiting accords with the

expectations of common sense. Alexander's successors acted according

to the law of the jungle, and Soter's first need was to secure himself

militarily against treachery or invasion. On marching away to the East in

331

B.C.

Alexander the Great had left an occupation force in Egypt of

20,000 men, presumably Macedonians and Greeks, under the command

of the Macedonians Balacrus and Peucestas. The latter was presumably

commander at Memphis, since an 'out-of-bounds' notice to his Greek

troops has been found at Saqqara.

9

As capital of Egypt and key to the

Delta and the Nile valley Memphis must have been garrisoned. Balacrus

may have commanded at Pelusium, the frontier town on the land route

6

Diod.

xvm.14.1.

7

Bengtson 1967, 111.15: (A 6).

9

From the Egyptian New Kingdom a classic example is the decree of Horemheb, the general

who became Pharaoh after Tutankhamun, Breasted 1905, 111.22-33: (F 154) (revised version and

translation in Pfluger 1946, 260-76:

(F

163);

Smith 1969, 209:

(F

166). Examples from the Ptolemaic

period are also discussed by Wilcken, UPZi. p. 497; Koenen 1957:

(F

273); they do not include the

present passage. The best known is P. Tebt, I.J (see below, p. 162). See also above, p. 83.

• Turner 1974, 239: (F 336).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

124 5 PTOLEMAIC EGYPT

from Syria.

A

fleet

of

thirty warships was commanded by Polemon son

of Theramenes.

It is

highly probable that Soter continued these

arrangements. Pelusium was shortly to hold up

a

succession of would-be

invaders; Memphis was the goal which Perdiccas failed

to

reach

in

321

B.C.

A

garrison

may

have continued

to man the

southern frontier

at

Elephantine.

The

Persians

had

maintained

a

detachment

of

Jews

on

guard duty there (some of their Aramaic documents may date as late as

the time

of

Soter

10

).

A

Greek marriage-contract drawn

up in

311

B.C.

(probably in Egypt because of its dating formula) and found there shows

a

Greek presence at Elephantine early in Soter's reign. But their task may

have been civil,

not

military.

A

Greek papyrus letter

of

about 250 B.C.

mentions Greek soldiers billeted near Edfu. Soter's only Greek city

foundation, named Ptolemais after him and sited

in

Upper Egypt near

the modern Assiut, must have contributed to the stability of that region.

A skeleton order

of

battle

of

the Ptolemaic forces

at

Gaza

in

3 12

B.C.

can

be

extracted from Diodorus.

11

Soter marched

to

Pelusium with

18,000 foot soldiers

and

4,000 cavalry composed

of

Macedonians,

of

mercenaries and of

a

mass

{plethos)

of

Egyptians; of the latter 'some had

missile weapons

or

other [special] equipment, some were fully armed

[that is,

for

the hoplite phalanx] and were serviceable

for

battle'.

In

307

B.C. Demetrius was surprised that those

of

Soter's troops

he

had taken

prisoner at Cyprian Salamis refused to change sides. ' They had left their

gear

(aposkeuai)

behind

in

Egypt with Soter.'

12

Mercenaries

at

this date

normally changed sides without fuss.

It

looks

as

though Demetrius'

prisoners

in 307

B.C. were cleruchs

(klerouchoi),

later called katoikoi,

professional soldiers attracted

by

Soter

to

serve

as a

reserve army

by

settling them

in

Egypt on holdings

of

land. Perhaps the policy decision

to settle cleruchs

in

Egypt was taken early

in

Soter's rule. By inducing

experienced foreign soldiers

to

settle

in

Egypt Soter could expect their

loyalty: they had a stake in their adopted country as well

as

the means of a

permanent livelihood. The concept of small-holder soldiers sprang from

three sources:

it was in

conformity with Macedonian custom;

it had

precedents in Pharaonic Egypt, and under the Saites the

machimoi

(native

soldiers) had enjoyed personal small-holdings often arouras and come to

the notice

of

Herodotus;

a

third source

was the

Athenian cleruchic

system, an origin which must be taken seriously.

13

Expropriation of land

above

all had

caused bitter enmity towards

the

Athenian cleruchs;

no

10

Harmatta 1961, 149: (F 256), dating these documents

to

about 310 B.C.

11

Diod. xiN.80.4.

12

Diod. xx.47.4.

13

The argument can only

be

sketched here. The Athenian institution had

a

long and complex

history. One must take into consideration not only the Athenian decree of the late sixth century B.C.

about the Salaminian settlers (ML no. 14), but Thucydides' statement

at

IN.

50

(with the comments

of A. W.Gomme,/4 Historical

Commentary on

Thucydides(Oxford,

1945-81)11.3 27-3 2)

of the terms on

which cleruchs were sent to Lesbos in

427

B.C.

It

should be noted that in 322

B.C.

Athenian cleruchs

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PTOLEMY I 12$

evidence has survived to show whether similar displacements made

Soter a target of resentment (traces of such feelings are found in the

rather different conditions of the Fayyum in the 250s B.C.). It is quite

possible that there was exploitable, but never irrigated, good land

available without the need to displace sitting tenants. A decision to

attract foreigners to settle in Egypt to serve as a professional soldiery

could be presented to Egyptians without the implication of Egyptian

military inferiority. The new method had an advantage over that used

against the Persians between 404 and 342 B.C., when Egypt had

depended on the assistance of Greek professional fighters. On com-

pletion of their contract these fighters had returned to their homes in

Greece carrying their golden handshake in the form of specially minted

coin. By settling them on the soil of Egypt the satrap retained the

coinage in Egypt, perhaps brought additional land under cultivation

and offered his troops a permanent retainer. Such might have been the

presentation of

a

policy destined to have far-reaching consequences. De

facto the new military settlers were in a privileged social and economic

class;

de facto

their dispersal through the length and breadth of Egypt

drew attention to the Greek way of life; moreover it provided an

unobtrusive military solution for an occupying power. Garrison towns

could be few in number, and Soter could adhere to the principle of

Alexander the Great (it was probably much older) that civil and military

authorities were to be kept separate.

If it was true that only Macedonians or troops of equivalent

equipment, training and resoluteness could meet Macedonians in the

phalanx it was also true that in

a

barter economy only Greeks knew how

to put coined money profitably to work. Moreover only a Macedonian

princess could provide Soter with an heir acceptable to Macedonians.

Charmers though the Egyptian girls were, only one of Soter's many

mistresses was Egyptian. Of

the

six persons described before 300

B.C.

as

particular friends of the king

—

Andronicus, Argaeus, Callicrates,

Manetho, Nicanor, Seleucus, the nucleus of the later court hierarchy

—

only one, Manetho, was Egyptian.

14

Without any overt declaration of

policy or rejection of partnership, a pattern was being set. It was to

Macedonians and Greeks that the Macedonian ruler gave positions of

command in the army or the elite troops, of executive decision-making

in the administration, and of trend-setting in court manners and

etiquette. Greek became the language of polite society, of administ-

who had been settled in Samos for forty years were evicted on the return to their homes of the native

Samians. The recruiting agents of Soter must have notified him of their availability, for it is the year

after his need for soldiers had begun to make itself felt. In the third century

B.C.

it is possible to list

by name from papyrus documents some twelve cleruchs in Egypt of Athenian origin.

11

Mooren 1978, 54: (F 288).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

I

2

6 5 PTOLEMAIC EGYPT

ration

and of

command.

In

their own country Egyptians required

the

help

of an

established corps

of

interpreters

(met

later

in the

Zenon

papyri)

to

approach authority.

The view just outlined has

not

been universally accepted

by

modern

historians. Some have argued that Soter's satrapship

was

consciously

Egyptianizing

at its

beginning,

and

that only later

did the

pendulum

swing

in

favour

of

a pro-Greek policy. They point

to

the high military

office held

by

Nectanebo (Nekhtnebef), described

in his

hieroglyphic

memorial (of Ptolemaic date) as 'nomarch

of

Sile

and

at

Sebennytus [i.e.

of Nomes XIV and XII], commander

of

foreigners

in

Nome XIV and

commander-in-chief of

his

majesty's armies'. The titles (and precision in

translation does

not

come easily) may

be

inflated. The third may mean

commander

of

(Jewish?) mercenaries,

the

last 'Commander-in-chief of

Egyptian troops'. This Nectanebo

was

grandson

of an

Egyptian

military commander,

and his

maternal grandmother

was

sister

to

Nectanebo

I

(380—363), among the last

of

Egypt's native kings.

15

They

point also

to

Petosiris, priest

and

magnate, whose influential family,

owning great estates

at

Hermopolis, can

be

traced

for

two generations

before

and

after him. Inscriptions

in his

exquisite private tomb pour

scorn

and

detestation

on

unnamed intruding sovereigns (they must

be

the Persians),

16

and by

inference

he

built

his

tomb

and

composed

its

inscription under

the

Ptolemies. Attention

is

also drawn

to the

sympathetic account

of

ancient Egypt (largely utilized

by

Diodorus)

written

in

Greek

by

Hecataeus

of

Abdera before

315 B.C.,

when

Theophrastus quotes

it;

17

and to

Soter's friendly relations with

the

Egyptian priesthood revealed

in the

hieroglyphic satrap stele

18

and in

the encomia bestowed therein

on

the Pharaoh Qabbash (as yet unplaced

in time).

It is

further urged

in

favour

of

this view that Soter

did not at

once make Alexandria his capital but kept his headquarters

at

Memphis,

where the satrap maintained

a

palace in royal state and furnished the first

resting-place

for

the body of Alexander the Great, hijacked by a resolute

stroke

of

propaganda as the

cortege

was on its way

to

the Oasis

of

Siwah.

But these examples will not sustain the thesis. Nekhtnebef's is the last

known case

of

what might

be

expected

if

Egyptian troops were

employed; Petosiris is the last known Egyptian landowner

to

have built

a family tomb designed and painted

in the old

tradition

of

the nobles;

even if Soter commissioned Hecataeus to write a work as briefing for his

administrators,

no

commitment

to

continue Pharaonic policy

is in-

15

Confusion

has

been caused

by the

conventional rendering 'prince'.

16

See considerations adduced by Lefebvre 1923-4:

(F

378) and further particularized by Roeder

'939.

73>ff-

(

F

}*')•

17

Eicholz

•

965,

8-12:

(j

5), quoted

by

Murray 1970, 143:

(1

49); see further Stern

and

Murray

•973.

M9

ff

-

:

(

F

369)-

18

English translation

in

Bevan 1927, 28-32: (F

127).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008