Wallenfeldt J. The American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812: People, Politics, and Power

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Published in 2010 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.)

in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright © 2010 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica,

and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. All

rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright © 2010 Rosen Educational Services, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Je Wallenfeldt: Manager, Geography and History

Rosen Educational Services

Hope Lourie Killcoyne: Senior Editor and Project Manager

Alexandra Hanson-Harding: Editor

Nelson Sá: Art Director

Matthew Cauli: Designer

Introduction by Alexandra Hanson-Harding

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812: people, politics, and power /

edited by Je Wallenfeldt.—1st ed.

p. cm.—(America at war)

“In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.”

Includes index and bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-61530-049-5 (eBook)

1. United States—History—Revolution, 1775–1783. 2. United States—History—War of 1812.

3. United States—History—Revolution, 1775–1783—Campaigns. 4. United States—History—

War of 1812—Campaigns. 5. United States—Foreign relations—Great Britain. 6. Great

Britain—Foreign relations—United States. I. Wallenfeldt, Jerey H.

E208.A447 2010

973.3—dc22

2009038296

On the cover: The Battle of Bunker Hill was the first major battle of the American

Revolution. This illustration, after an oil painting by American painter John Trumbull,

depicts the death of General Joseph Warren, June 17, 1775. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Introduction 8

Chapter 1: Prelude to the American

Revolution 17

Legacy of the Great War for the Empire 18

The Tax Controversy 20

Constitutional Dierences with Britain 23

The Boston Massacre 28

The Intolerable Acts 28

Chapter 2: Independence 33

The First Continental Congress 33

The Second Continental Congress 36

The Declaration of Independence 39

Chapter 3: The American Revolution:

An Overview 42

Land Campaigns to 1778 42

Land Campaigns from 1778 47

The War at Sea 57

Chapter 4: The Battles of the American

Revolution 62

Battles of Lexington and Concord 62

Battle of Bunker Hill 63

Battle of Ticonderoga 65

Siege of Boston 65

Battle of Quebec 66

Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge 66

Battle of Long Island 66

Battle of White Plains 67

Battles of Trenton and Princeton 67

Battles of Saratoga 69

Battle of Oriskany 69

Battle of Bennington 70

Battle of the Brandywine 70

Battle of Germantown 70

Valley Forge 71

Battle of Monmouth 72

CONTENTS

40

49

71

Engagement Between Bonhomme Richard and

Serapis 72

Siege of Charleston 74

Battle of Camden 74

Battle of Kings Mountain 75

Battle of Cowpens 75

Battle of Guilford Courthouse 75

Battle of Virginia Capes 76

Battle of Eutaw Springs 76

Siege of Yorktown 76

Battle of the Saintes 78

Chapter 5: Military Figures of the

American Revolution 79

The American Side 79

The British Side 120

Chapter 6: Nonmilitary Figures of the

American Revolution 130

The American Side 130

The British Side 160

Aftermath 172

Chapter 7: The War of 1812: Major

Causes 175

Impressments 176

Chapter 8: The War of 1812: An

Overview 181

The Continuing Stuggle 189

Chapter 9: The Battles of the War

of 1812 197

Battle of Queenston Heights 197

Battle of Lake Erie 197

Battle of the Thames 198

Battle of Châteauguay 199

Battle of Crysler's Farm 199

Battle of Chippewa 200

Battle of Lundy's Lane 200

Battle of Plattsburgh 200

89

155

201

Battle of New Orleans 201

Chapter 10: Military Figures of the

War of 1812 203

The American Side 203

The British Side 216

Chapter 11: Nonmilitary Figures of the

War of 1812 219

The American Side 219

The British Side 226

Final Stages of War and Aftermath 229

Glossary 230

Bibliography 231

Index 233

208

218

221

Introduction | 9

American seamstress Betsy Ross is said to have created the original 13-star fl ag used by

the colonies. On June 14, 1777, the Continental Congress adopted the Stars and Stripes as the

national fl ag of the United States. © www.istockphoto.com/Nic Taylor

learn what factors led up to these wars,

the American Revolution and the War of

1812. You will discover their major causes

and get an overview of each war’s actions.

You will encounter the major battles and

meet the extraordinary people—both

military and civilian—who led the nation

through each confl ict. As you read, you

will see how the business of separating

from Britain was not truly settled until

after the War of 1812, which some have

called “The Second War of American

Independence.”

In this book, you will discover how

belonging to the British Empire gave the

American colonists a sense of identity, a

reliable trading partner, and an army to

protect them. You will also learn that,

when the British required the American

colonists to pay taxes, outraged Amer-

icans refused because they lacked

representation in Britain’s Parliament.

At fi rst it might seem strange that

Americans would fi ght a war over some-

thing as modest as taxes. Certainly other

peoples in the history of the world have

su ered greater indignity and oppression

but there were good reasons why “taxa-

tion without representation” became a

rallying cry that led to the war.

When King George III of England

was young, his mother told him,

“George, be a King.” He grew up deter-

mined to assert that royal power and

W

hen you think of the American

Revolution, you may picture John

Hancock signing the Declaration of

Independence with a fl ourish. Perhaps

you envision the fi ery orations of Samuel

Adams or imagine Minutemen fi ring

muskets at Redcoats as they practice the

form of guerrilla warfare they learned

from their Indian neighbours. It can be

hard to relate to these 18th-century people,

with their powdered perukes, their lofty,

ornate language, and what may seem to

some as their willingness to fi ght to the

death over the inconvenience of paying

some small taxes imposed on them with-

out consent. Indeed, it may seem puzzling

that the colonists would choose to sepa-

rate themselves from a powerful empire

that not only came to their defense in the

French and Indian War just two decades

earlier but was also a ready trading part-

ner for American goods. But the

individuals who fought in the American

Revolution were not merely quaint fi g-

ures in a book. They were real people

who risked death for a vision of what

America could be and what kinds of

rights free people deserved.

Today the United States and Great

Britain are close allies who share a lan-

guage, culture, and a similar outlook on

the world. But in the early days of the

United States they fought two fi erce wars

against each other. In this book, you will

10 | The American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812: People, Politics, and Power

colonials’ insubordination. To punish the

defiant Boston residents, the British gov-

ernment enacted the Boston Port Bill,

which closed the city's ocean-going

trade pending payment for the dumped

tea, and occupied the city. This harsh

response made many Americans ques-

tion the wisdom of their loyalty to Britain

even more.

As these tensions grew, representa-

tives from the 13 colonies met as the

Second Continental Congress in Phila-

delphia. They decided to send the king

the Olive Branch Petition, a last-ditch

eort to explain the colonists’ complaints

and find common ground. But they were

rebued, and finally, there was no turning

back. Written primarily by Thomas

Jeerson and signed by the delegates,

the Declaration of Independ ence

asserted that “all men are created equal”

and established the colonists’ claims to

what they considered their God-given

rights to “life liberty, and the pursuit of

happiness.” It laid out America’s claim to

be an independent country, as well as its

grievances with Britain’s monarch—

though in fact, much of the colonists’

anger was actually directed at its Parlia-

ment. The war had ocially begun.

By the time the Declaration of

Independence was signed, the war was

already more than a year old. It had

started on April 19, 1775, when colonial

Minutemen fought fiercely against

British soldiers dispatched to seize the

Americans’ stores of ammunition in

Lexington, Mass. This first battle was a

became an old-fashioned, inflexible ruler.

Unfortunately, he came of age in a time

when change was in the air. The 18th

century was the time of the Age of

Enlightenment. During that era, philoso-

phers questioned the traditional order

of society. Instead of valuing blind obedi-

ence to a sovereign, they championed

individual rights, what they termed

“natural rights.” Americans came to feel

particularly strongly about their rights.

Because they lived so far from their ruling

home country—an ocean voyage could

easily take two months—the colonists had

a long history of governing themselves

with little interference from the king or

Parliament.

The colonists’ road to independence

started with a series of escalating boycotts

and protests. When Britain tried to tax

legal documents, colonists rioted. When

the British taxed cloth, colonists made

their own homespun fabric. When they

taxed tea, colonists dumped a shipment

of tea in Boston Harbor. Americans had

rarely been taxed before and felt that

paying a tax they hadn't agreed to was

the first step in submitting to treatment

other British subjects would not tolerate.

Even worse, Parliament passed a law

explicitly stating that it had the right to

make laws for the colonies in all matters.

Thomas Jeerson called acts like these

nothing less than “a deliberate system-

atical plan of reducing us to slavery.”

Furious colonists wrote angry newspaper

articles. Mobs rioted. In England,

Parliamentary leaders were angry at the

Introduction | 11

until you see the whites of their eyes!”

The British were led by Gen. William

Howe, an experienced soldier who had

opposed Parliament’s coercive legisla-

tion toward the colonies and favoured

reconciliation yet eventually took com-

mand of the British forces in North

America. Though the colonists were

forced to retreat, the British had more

than 1,000 casualties. The loss of so

many men deeply a ected Howe, who

wrote of the outcome, “The success is too

dearly bought.”

shock to the British, who believed that

the ill-trained American farmers could

not seriously challenge them. Realizing

that the Americans meant business, the

British called for reinforcements. Mean-

while, Americans also prepared for war

by sending Gen. George Washington to

Boston as the head of the newly formed

Continental Army.

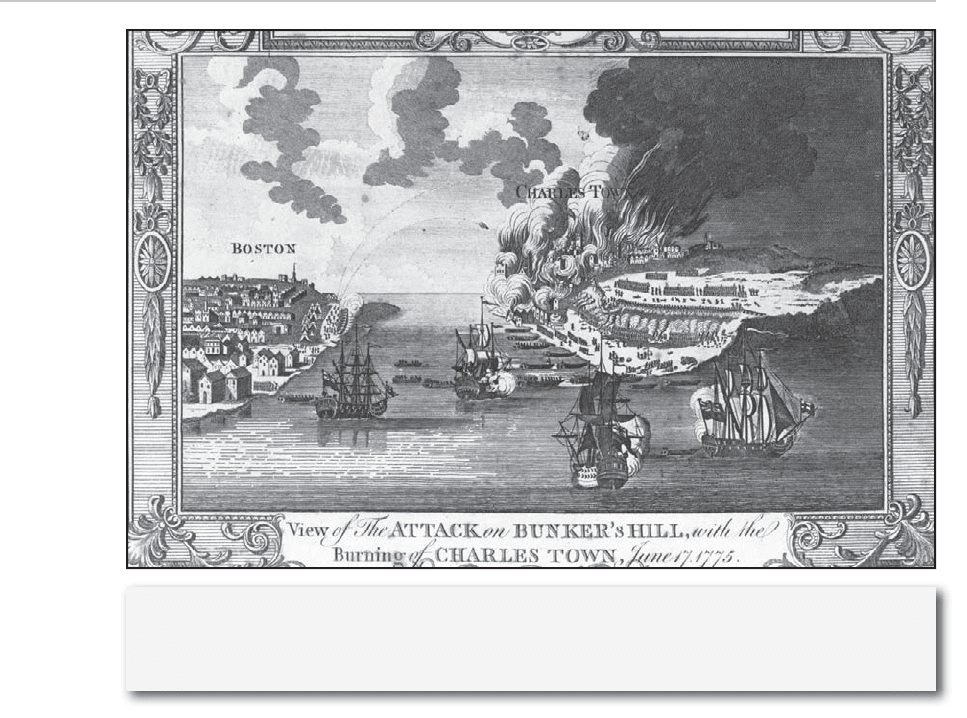

A few months later, the two sides

clashed again at the Battle of Bunker Hill

near Boston where the Americans were

given the famous command, “Don’t shoot

This engraving depicts the attack on Bunker Hill and the burning of Charlestown in Boston

Harbor, 1775. The fi rst major battle of the war, Bunker Hill was a Pyrrhic victory for the

British. MPI/Hulton Archive/Getty Images