Wallenfeldt J. The American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812: People, Politics, and Power

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Being generally master of my time, I spend a good deal of it in a library, which I think

the most valuable part of my small estate; and being acquainted with two or three gentle-

men of abilities and learning who honor me with their friendship, I have acquired, I

believe, a greater share of knowledge in history and the laws and constitution of my coun-

try than is generally attained by men of my class, many of them not being so fortunate as

I have been in the opportunities of getting information.

From infancy I was taught to love humanity and liberty. Inquiry and experience have

since confi rmed my reverence for the lessons then given me by convincing me more fully

of their truth and excellence. Benevolence toward mankind excites wishes for their wel-

fare, and such wishes endear the means of fulfi lling them. These can be found in liberty

only, and therefore her sacred cause ought to be espoused by every man, on every occa-

sion, to the utmost of his power. As a charitable but poor person does not withhold his

mite because he cannot relieve all the distresses of the miserable, so should not any hon-

est man suppress his sentiments concerning freedom, however small their infl uence is

likely to be. Perhaps he may “touch some wheel” that will have an e ect greater than he

could reasonably expect.

These being my sentiments, I am encouraged to o er to you, my countrymen, my

thoughts on some late transactions that appear to me to be of the utmost importance to

you. Conscious of my defects, I have waited some time in expectation of seeing the sub-

ject treated by persons much better qualifi ed for the task; but being therein disappointed,

and apprehensive that longer delays will be injurious, I venture at length to request the

attention of the public, praying that these lines may be read with the same zeal for the

happiness of British America with which they were written.

With a good deal of surprise I have observed that little notice has been taken of an

act of Parliament, as injurious in its principle to the liberties of these colonies as the

Stamp Act was: I mean the act for suspending the legislation of New York.

The assembly of that government complied with a former act of Parliament, requir-

ing certain provisions to be made for the troops in America, in every particular, I think,

except the articles of salt, pepper, and vinegar. In my opinion they acted imprudently,

considering all circumstances, in not complying so far as would have given satisfaction

as several colonies did. But my dislike of their conduct in that instance has not blinded

me so much that I cannot plainly perceive that they have been punished in a manner

pernicious to American freedom and justly alarming to all the colonies.

If the British Parliament has a legal authority to issue an order that we shall furnish a

single article for the troops here and to compel obedience to that order, they have the

same right to issue an order for us to supply those troops with arms, clothes, and every

necessary, and to compel obedience to that order also; in short, to lay any burdens they

please upon us. What is this but taxing us at a certain sum and leaving to us only the

manner of raising it? How is this mode more tolerable than the Stamp Act? Would that

act have appeared more pleasing to Americans if, being ordered thereby to raise the sum

Prelude to the American Revolution | 25

26 | The American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812: People, Politics, and Power

total of the taxes, the mighty privilege had been left to them of saying how much should

be paid for an instrument of writing on paper, and how much for another on parchment?

An act of Parliament commanding us to do a certain thing, if it has any validity, is a

tax upon us for the expense that accrues in complying with it, and for this reason, I believe,

every colony on the continent that chose to give a mark of their respect for Great Britain,

in complying with the act relating to the troops, cautiously avoided the mention of that

act, lest their conduct should be attributed to its supposed obligation.

The matter being thus stated, the assembly of New York either had or had not a right

to refuse submission to that act. If they had, and I imagine no American will say they had

not, then the Parliament had no right to compel them to execute it. If they had not that

right, they had no right to punish them for not executing it; and therefore had no right to

suspend their legislation, which is a punishment. In fact, if the people of New York cannot

be legally taxed but by their own representatives, they cannot be legally deprived of the

privilege of legislation, only for insisting on that exclusive privilege of taxation. If they

may be legally deprived in such a case of the privilege of legislation, why may they not,

with equal reason, be deprived of every other privilege? Or why may not every colony be

treated in the same manner, when any of them shall dare to deny their assent to any impo-

sitions that shall be directed? Or what signifi es the repeal of the Stamp Act, if these

colonies are to lose their other privileges by not tamely surrendering that of taxation?

There is one consideration arising from the suspension which is not generally attended

to but shows its importance very clearly. It was not necessary that this suspension should be

caused by an act of Parliament. The Crown might have restrained the governor of New York

even from calling the assembly together, by its prerogative in the royal governments. This

step, I suppose, would have been taken if the conduct of the assembly of New York had been

regarded as an act of disobedience to the Crown alone. But it is regarded as an act of “dis-

obedience to the authority of the British legislature.” This gives the suspension a consequence

vastly more a ecting. It is a parliamentary assertion of the supreme authority of the British

legislature over these colonies in the point of taxation; and it is intended to compel New York

into a submission to that authority. It seems therefore to me as much a violation of the lib-

erty of the people of that province, and consequently of all these colonies, as if the Parliament

had sent a number of regiments to be quartered upon them, till they should comply.

For it is evident that the suspension is meant as a compulsion; and the method of

compelling is totally indi erent. It is indeed probable that the sight of red coats and the

hearing of drums would have been most alarming, because people are generally more

infl uenced by their eyes and ears than by their reason. But whoever seriously considers

the matter must perceive that a dreadful stroke is aimed at the liberty of these colonies. I

say of these colonies; for the cause of one is the cause of all. If the Parliament may lawfully

deprive New York of any of her rights, it may deprive any or all the other colonies of their

rights; and nothing can possibly so much encourage such attempts as a mutual inatten-

tion to the interest of each other. To divide and thus to destroy is the fi rst political maxim

The o cial British reply to the colo-

nial case on representation was that the

colonies were “virtually” represented in

Parliament in the same sense that the

large voteless majority of the British

public was represented by those who did

vote. To this Otis snorted that, if the

majority of the British people did not

have the vote, they ought to have it. The

idea of colonial members of Parliament,

several times suggested, was never a

likely solution because of problems of

time and distance and because, from the

colonists’ point of view, colonial members

would not have adequate infl uence.

The standpoints of the two sides to

the controversy could be traced in the lan-

guage used. The principle of parliamentary

sovereignty was expressed in the language

of paternalistic authority; the British

referred to themselves as parents and to

the colonists as children. Colonial Tories,

who accepted Parliament’s case in the

interests of social stability, also used

this terminology. From this point of

view, colonial insubordination was

“unnatural,” just as the revolt of children

against parents was unnatural. The colo-

nists replied to all this in the language

of rights . They held that Parliament could

do nothing in the colonies that it could not

do in Britain because the Americans were

protected by all the common-law rights

of the British. (When the First Continental

Congress met in September 1774, one of

its fi rst acts was to a rm that the

in attacking those who are powerful by their union. He certainly is not a wise man who

folds his arms and reposes himself at home, seeing with unconcern the fl ames that have

invaded his neighbor’s house without using any endeavors to extinguish them. When Mr.

Hampden’s ship-money cause for 3s. 4d. was tried, all the people of England, with anxious

expectations, interested themselves in the important decision; and when the slightest

point touching the freedom of one colony is agitated, I earnestly wish that all the rest may

with equal ardor support their sister. Very much may be said on this subject, but I hope

more at present is unnecessary.

With concern I have observed that two assemblies of this province have sat and

adjourned without taking any notice of this act. It may perhaps be asked: What would

have been proper for them to do? I am by no means fond of infl ammatory measures. I

detest them. I should be sorry that anything should be done which might justly displease

our sovereign or our mother country. But a fi rm, modest exertion of a free spirit should

never be wanting on public occasions. It appears to me that it would have been su cient

for the assembly to have ordered our agents to represent to the Kings ministers their

sense of the suspending act and to pray for its repeal. Thus we should have borne our

testimony against it; and might therefore reasonably expect that on a like occasion we

might receive the same assistance from the other colonies.

Small things grow great by concord.

A Farmer

Prelude to the American Revolution | 27

28 | The American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812: People, Politics, and Power

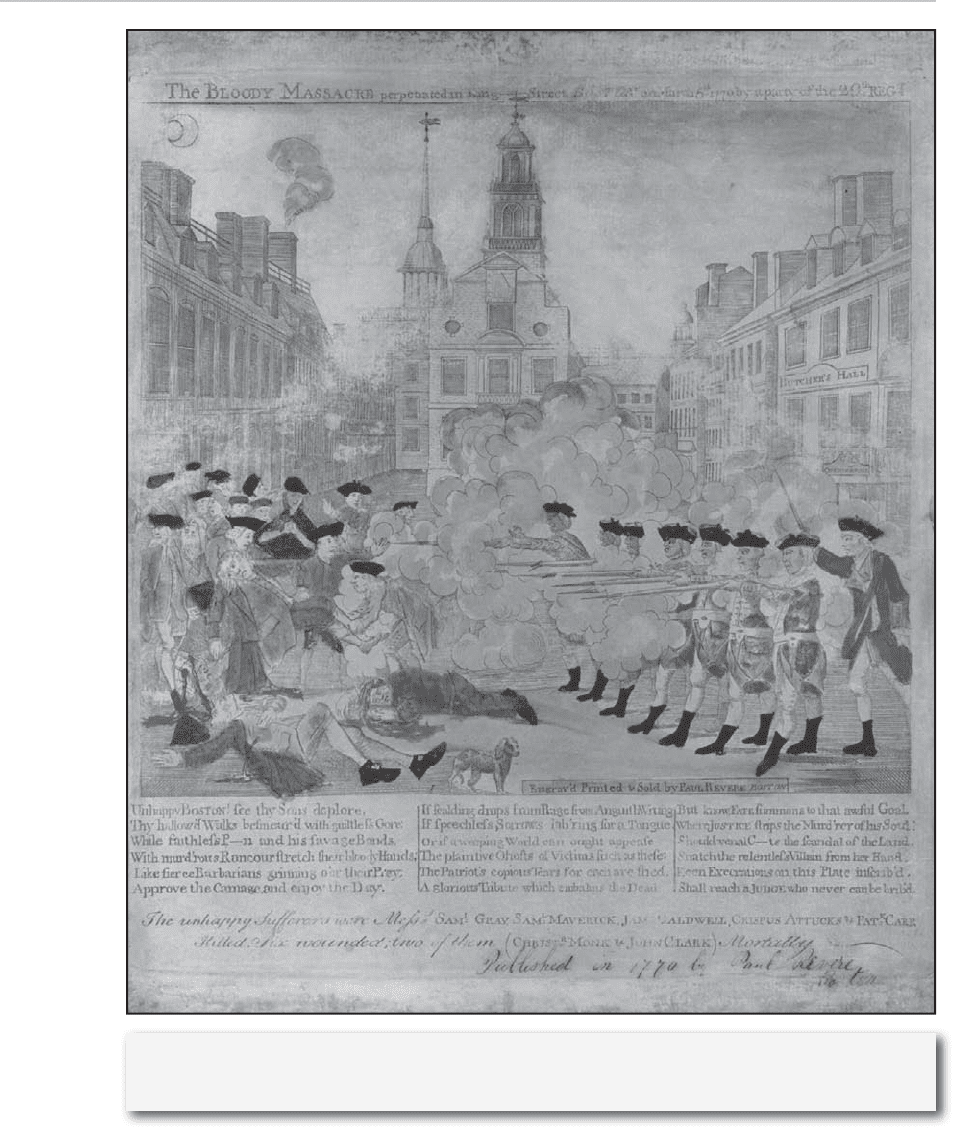

ThE BOSTON MASSACRE

One of the most violent clashes occurred

in Boston on March 5, 1770, just before the

repeal of the Townshend duties. The inci-

dent, which became known as the Boston

Massacre, was the climax of a series of

brawls in which local workers and sailors

clashed with British soldiers quartered in

Boston. Harassed by a mob, the troops

opened fire. Crispus Attucks, a black

sailor and former slave, was shot first and

died along with four others. Samuel

Adams, a skillful propagandist of the day,

shrewdly depicted the aair as a battle for

American liberty. His cousin John Adams,

however, successfully defended the British

soldiers tried for murder in the aair.

The other serious quarrel with British

authority occurred in New York, where

the assembly refused to accept all the

British demands for quartering troops.

Before a compromise was reached,

Parliament had threatened to suspend

the assembly. The episode was ominous

because it indicated that Parliament was

taking the Declaratory Act at its word;

on no previous occasion had the British

legislature intervened in the operation of

the constitution in an American colony.

(Such interventions, which were rare, had

come from the crown.)

ThE INTOLERABLE ACTS

In retaliation to the Boston Massacre and

other provocations, including the Boston

Tea Party (see sidebar), in the spring of

1774, with hardly any opposition,

colonies were entitled to the common

law of England.)

Rights, as Richard Bland of Virginia

insisted in The Colonel Dismounted (as

early as 1764), implied equality. And here

he touched on the underlying source of

colonial grievance. Americans were being

treated as unequals, which they not only

resented but also feared would lead to a

loss of control of their own aairs.

Colonists perceived legal inequality

when writs of assistance—essentially,

general search warrants—were authorized

in Boston in 1761 while closely related

“general warrants” were outlawed in two

celebrated cases in Britain. Townshend

specifically legalized writs of assistance

in the colonies in 1767. Dickinson

devoted one of his Letters from a Farmer

to this issue.

When Lord North became prime

minister early in 1770, George III had at

last found a minister who could work

both with himself and with Parliament.

British government began to acquire

some stability. In 1770, in the face of the

American policy of nonimportation,

the Townshend taris were withdrawn—

all except the tax on tea, which was kept

for symbolic reasons. Relative calm

returned, though it was rued on the

New England coastline by frequent inci-

dents of defiance of customs ocers, who

could get no support from local juries.

These outbreaks did not win much sym-

pathy from other colonies, but they were

serious enough to call for an increase in

the number of British regular forces sta-

tioned in Boston.

This depiction of the Boston Massacre was engraved by famous Revolutionary Paul Revere.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Prelude to the American Revolution | 29

30 | The American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812: People, Politics, and Power

The Townshend Acts passed by Parliament in 1767 imposed duties on various products imported

into the British colonies and raised such a storm of colonial protest and noncompliance that they

were repealed in 1770, saving the duty on tea, which was retained by Parliament to demonstrate its

presumed right to raise such colonial revenue without colonial approval. The merchants of Boston

circumvented the act by continuing to receive tea smuggled in by Dutch traders. In 1773 Parliament

passed a Tea Act designed to aid the fi nancially troubled East India Company by granting it (1) a

monopoly on all tea exported to the colonies, (2) an exemption on the export tax, and (3) a “draw-

back” (refund) on duties owed on certain surplus quantities of tea in its possession. The tea sent to

the colonies was to be carried only in East India Company ships and sold only through its own

agents, bypassing the independent colonial shippers and merchants. The company thus could sell

the tea at a less-than-usual price in either America or Britain; it could undersell anyone else. This

plan naturally aff ected colonial merchants, and many colonists denounced the act as a plot to

induce Americans to buy—and therefore pay the tax on—legally imported tea. The perception of

monopoly drove the normally conservative colonial merchants into an alliance with radicals led by

Samuel Adams and his Sons of Liberty. Boston was not the only port to threaten to reject the casks

of taxed tea, but its reply was the most dramatic—and provocative.

In such cities as New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston, tea agents resigned or canceled orders,

and merchants refused consignments.

In Boston, however, the royal governor

Thomas Hutchinson determined to

uphold the law and maintained that

three arriving ships, the Dartmouth,

Eleanor, and Beaver, should be allowed

to deposit their cargoes and that appro-

priate duties should be honoured. On

the night of Dec. 16, 1773, a group of

about 60 men, encouraged by a large

crowd of Bostonians, donned blankets

and Indian headdresses, marched to

Gri n’s wharf, boarded the ships, and

dumped 342 tea chests, belonging to

the East India Company and valued

at £18,000 ($29,500), into the water.

The British opinion was outraged, and

America’s friends in Parliament were

immobolized. American merchants in

other cities were also disturbed. Prop-

erty was property.

In Focus: The Boston Tea Party

at £18,000 ($29,500), into the water.

The British opinion was outraged, and

America’s friends in Parliament were

immobolized. American merchants in

other cities were also disturbed. Prop-

erty was property.

On Dec. 16, 1773, Bostonians dressed in Native

American clothing threw imported tea into Boston

Harbor in protest against the Tea Act. MPI/Hulton

Archive/Getty Images

One of the “Intolerable Acts” was the Quartering Act of June 2, 1774, which applied to all British

America and gave colonial governors the right to requisition unoccupied buildings to house Brit-

ish troops. However, in Massachusetts the British troops were forced to remain camped on the Boston

Common until the following November because the Boston patriots refused to allow workmen to

repair the vacant buildings Gen. Thomas Gage had obtained for quarters. Source: The Statutes at

Large [of Great Britain], Danby Pickering, ed., Cambridge (England), various dates, Vol. XXX.

Whereas doubts have been entertained whether troops can be quartered otherwise than

in barracks, in case barracks have been provided su cient for the quartering of all the

o cers and soldiers within any town, township, city, district, or place within His Majesty’s

dominions in North America; and whereas it may frequently happen from the situation of

such barracks that, if troops should be quartered therein they would not be stationed

where their presence may be necessary and required: be it therefore enacted by the King’s

Most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords . . . and Commons,

in this present Parliament assembled … that, in such cases, it shall and may be lawful for

the persons who now are, or may be hereafter, authorized by law, in any of the provinces

within His Majesty’s dominions in North America, and they are hereby respectively

authorized, empowered, and directed, on the requisition of the o cer who, for the time

being, has the command of His Majesty’s forces in North America, to cause any o cers

or soldiers in His Majesty’s service to be quartered and billeted in such manner as is now

directed by law where no barracks are provided by the colonies.

2. And be it further enacted by the authority aforesaid that, if it shall happen at any

time that any o cers or soldiers in His Majesty’s service shall remain within any of the

said colonies without quarters for the space of twenty-four hours after such quarters shall

have been demanded, it shall and may be lawful for the governor of the province to order

and direct such and so many uninhabited houses, outhouses, barns, or other buildings as

he shall think necessary to be taken (making a reasonable allowance for the same) and

make fi t for the reception of such o cers and soldiers, and to put and quarter such o cers

and soldiers therein for such time as he shall think proper.

3. And be it further enacted by the authority aforesaid that this act, and everything

herein contained, shall continue and be in force in all His Majesty’s dominions in North

America, until March 24, 1776.

Primary Source: The Quartering Act

Parliament passed the Coercive Acts, four

punitive measures designed to reduce

Massachusetts to order and imperial dis-

cipline. The fi rst of these measures, which

became known in the colonies as the

Intolerable Acts, was the Boston Port Bill,

closing that city’s harbour until restitu-

tion was made for the destroyed tea. In

the second, the Massachusetts Government

Act, Parliament abrogated the colony’s

Prelude to the American Revolution | 31

32 | The American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812: People, Politics, and Power

Ohio and Mississippi rivers from possible

colonial jurisdiction and awarded it to

Upper Canada (the southern section that

would eventually become the province of

Quebec), permanently blocking the pros-

pect of American control of western

settlement. By establishing French civil

law and the Roman Catholic religion in

the coveted area, Britain acted liberally

toward Quebec’s settlers but raised the

spectre of popery before the mainly

Protestant colonies to Canada’s south.

The Intolerable Acts represented an

attempt to reimpose strict British control

over the American colonies, but after 10

years of vacillation, the decision to be

firm had come too late. Rather than

cowing Massachusetts and separating it

from the other colonies, the oppressive

measures became the justification for

convening the First Continental Congress

later in 1774.

charter of 1691, reducing it to the level of

a crown colony, substituting a military

government under Gen. Thomas Gage. It

also outlawed town meetings—the famous

gatherings that had been forums for radi-

cal thinkers—as political bodies.

The third act, the Administration of

Justice Act, was aimed at protecting

British ocials charged with capital

oenses during law enforcement by

allowing them to go to England or

another colony for trial. The fourth

Coercive Act included new arrangements

for housing British troops in occupied

American dwellings, thus reviving the

indignation that surrounded the earlier

Quartering Act, which had been allowed

to expire in 1770.

To make matters worse, Parliament

also passed the Quebec Act. Under con-

sideration since 1773, this act removed all

the territory and fur trade between the

ThE FIRST CONTINENTAL CONGRESS

There was widespread agreement that the intervention in

colonial government represented by the Intolerable Acts

could threaten other provinces and could be countered only

by collective action. After much intercolonial correspondence,

a Continental Congress came into existence, meeting in

Philadelphia in September 1774. Every colonial assembly

except that of Georgia appointed and sent a delegation. The

Virginia delegation’s instructions were drafted by Thomas

Je erson and were later published as A Summary View of

the Rights of British America (1774). Je erson insisted on the

autonomy of colonial legislative power and set forth a highly

individualistic view of the basis of American rights. This

belief that the American colonies and other members of the

British Empire were distinct states united under the king and

thus subject only to the king and not to Parliament was

shared by several other delegates, notably James Wilson

and John Adams, and strongly infl uenced the Congress.

The Congress, comprising 56 deputies, convened on

Sept. 5, 1774. Peyton Randolph of Virginia was unanimously

elected president, thus establishing usage of that term as

well as “Congress.” Charles Thomson of Pennsylvania was

elected secretary and served in that o ce during the 15-year

life of the Congress.

Independence

Independence

ChAPTER 2

George Washington (standing) surrounded by members of the Continental Congress, litho-

graph by Currier & Ives, c. 1876. Currier & Ives Collection, Library of Congress, Neg. No.

LC-USZC2-3154

34 | The American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812: People, Politics, and Power