Weingast B.R., Wittman D. The Oxford Handbook of Political Economy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

chapter 9

..............................................................

COALITION

GOVERNMENT

..............................................................

daniel diermeier

1 Introduction:AShift in Perspective

.............................................................................

The year 1990 marked a turning point in the study of governmental coalitions. Laver

and Schofield (1990) published a comprehensive and detailed review of the field

up to the late 1980s. In addition, a significant set of new papers broke with the

established research traditions. First, Baron (1989) published the initial applications

of non-cooperative game theory (the “Baron–Ferejohn” model) to the study of gov-

ernmental coalitions (Baron and Ferejohn 1989). Second, Laver and Shepsle (1990)

used structure-induced equilibrium models to study the formation and stability of

cabinets. Third, Strom (1990) presented a comprehensive account of minority gov-

ernments and coalitional stability.

1

These papers had one important element in common: all focused on the role of

institutions in the study of governmental coalitions. The New Institutionalism had

arrived in the study of coalition government. The point of this new approach was not

that political institutions had been overlooked as a potentially important object of

study. Political institutions—such as party systems, electoral rules, or constitutional

features— have always played an important role in the study of coalition government.

Rather, the claim was methodological: to have explanatory content and empirical ac-

curacy, formal models of politics must incorporate institutional details.

2

This shift in

perspective has had important consequences for the praxis and progress of coalition

research in the last fifteen years.

¹ Laver (this volume) covers many of these issues in greater detail.

² See Diermeier (1997) and Diermeier and Krehbiel (2003) for a detailed discussion of the

methodological aspects of institutionalism.

daniel diermeier 163

It is the distinctive characteristic of parliamentary democracies that the executive

derives its mandate from and is politically responsible to the legislature. This has two

consequences. First, unless one party wins a majority of seats, a rare case in electoral

systems under proportional representation, the government is not determined by an

election alone, but is the result of an elaborate bargaining process among the parties

represented in the parliament. Second, parliamentary governments may lose the

confidence of the parliament at any time, which leads to their immediate termination.

Thus, historically, two questions have dominated the study of coalition government.

Which governments will form? And how long will they last? Institutionalism has

fundamentally changed the way researchers are conceptualizing and answering these

questions.

This chapter is designed as follows. I first discuss important empirical work that

motivated the institutionalist shift in the study of government coalitions. In the

next two sections I discuss the most widely used institutionalist approaches: Laver

and Shepsle’s structure-induced equilibrium approach and the sequential bargaining

model used by Baron and others. I then discuss two alternative approaches (demand

bargaining and efficient bargaining) to model coalition formation that try to over-

come some of the technical difficulties of older approaches. In the next two sections I

discuss the consequences of the institutionalist perspective for empirical work. First,

I review the area of cabinet stability, one of the most active areas in coalition research.

In the penultimate section I discuss recent work that relies on structural estimation

as its methodology to study coalition government empirically. A conclusion contains

a summary and discusses some open questions.

2 The Arrival of Institutionalism

.............................................................................

Institutionalism is difficult to define. It should not be identified with the analysis

of institutions. Rather it is a methodological approach. The common element to all

versions of institutionalism is a rejection of the social choice research program of

finding institution-free properties (as illustrated by McKelvey 1986). Beyond that, in-

stitutionalism consists of rather different research programs that stem from different

methodological approaches.

In the context of the study of government coalition the institutionalist approach

implies a re-evaluation of existing theoretical traditions. Consider Axelrod’s (1972)

theory of proto-coalitions as an example.

3

In his model, ideologically connected

proto-coalitions expand stepwise by adding new parties until they reach political

³ Axelrod’s theory of proto-coalitions is not the only example of an “institution-free” approach to

government coalitions. Other examples include cooperative bargaining theory (e.g. the Shapley value,

bargaining set) or social choice theoretic approaches (e.g. the core, the uncovered set). For a technically

very sophisticated example of recent work in this area see e.g. Schofield, Sened, and Nixon 1998.Their

model combines social choice-based, institution-free models of cabinet formation with Nash equilibria

at the electoral level.

164 coalition government

viability. The important point here is how the explanation works. Note that Axelrod’s

account only relies on the number of parties, their seat share, and their ideological

position. From the perspective of the theory, other aspects of the cabinet formation

process are irrelevant, e.g. who can propose governments, how long the process can

last. Some disregard of existing structure, of course, is the essence of formal modeling.

The question is whether such a stripped-down model of government formation

explains the empirical phenomena. To rephrase the famous quote by Einstein: models

should be as simple as possible, but not simpler.

The answer to this question is, of course, empirical. Are there phenomena that

cannot be explained with an institution-free approach? Before the institutional shift

in the early 1990s much of the empirical study of government coalitions was focused

on one issue: the question of government formation. That is, suppose we know the

number of parties, their seat shares, and (in some models) their ideological position,

which governments would form?

4

The success of this research program was mixed.

Although it consisted of a fruitful interplay of theoretical and empirical work, all told,

institution-free models failed to predict which governments would form.

Two roots in the literature helped introduce institutionalist models into the study

of government coalitions. The first root was empirical. Specifically, two independent

empirical traditions played a critical role: Kaare Strom’s work on minority cabinets

and Browne et al.’s study of cabinet stability. The second root was theoretical and

consistent in the development of institutionalist models of cabinet formation (Laver

and Shepsle 1990;Baron1989).

Strom’s work (1985, 1990) was important in various respects. First, it focused on

a puzzling, but prevalent, case of coalition governments: minority governments,

i.e. cabinets where the parties that occupy portfolios together do not control a ma-

jority of seats in the legislature. As Strom pointed out, their existence is neither rare

(roughly a third of all coalition governments are of the minority type), nor does it

constitute a crisis phenomenon. Denmark, for example, is almost always governed by

minority governments, but hardly qualifies as a polity in crisis. Moreover, many of

the minority governments are surprisingly stable.

The existence of minority governments constituted an embarrassment for existing

theories of coalition formation. Why don’t the opposition parties that constitute

a chamber majority simply replace the incumbent minority government by a new

cabinet that includes them?

The influence of Strom’s work, however, went beyond the mere recognition of

minority governments. It had important methodological consequences for the study

of coalition governments in general. First, it refocused the government forma-

tion question from “which government will form?” to “which type of government

will form?”

5

That is, what are the factors that lead some countries regularly to

choose minority cabinets (e.g. Denmark), while others (e.g. Germany) almost always

choose minimum winning coalitions, while yet others (e.g. Italy) frequently choose

⁴ See e.g. Laver and Schofield 1990 for a detailed overview of this literature.

⁵ See, however, Martin and Stevenson 2001 for a recent, institutional, empirical study of coalition

formation that tried to answer the first question.

daniel diermeier 165

super-majority governments. Second, it gave an account of minority governments us-

ing institutionalist explanations such as the existence of a strong committee system.

6

The second empirical tradition was the study of cabinet stability pioneered by

Browne, Srendreis, and Gleiber (1984, 1986, 1988). Browne et al. viewed cabinet sur-

vival as determined by “critical events,” exogenous random shocks that destabilize an

existing government. These random shocks are assumed to follow a Poisson process

which implies a constant hazard rate for cabinet terminations.

7

Strom’s (1985, 1988)

approach, on the other hand, was institutional. Here the goal was to identify a robust

set of covariates that influence mean cabinet duration. Since government type—

i.e. whether the cabinet had majority or minority status—was one of the proposed

independent variables, Strom’s approach thus integrated his work on cabinet stability

and minority governments.

In 1990 King et al. presented a “unified” model of cabinet dissolutions that com-

bined the attribute approach proposed by Strom (1985, 1988) and the events approach

introduced by Browne, Srendreis, and Gleiber (1986, 1988). Following this insight, a

whole list of papers, especially by Paul Warwick, pointed out that the unified model

isbutaspecialcaseofawholeclassofsurvivalmodels(Warwick1992a, 1992b, 1992c,

1994; Warwick and Easton 1992; Diermeier and Stevenson 1999, 2000).

While this literature provided rich new empirical regularities, an equally com-

pelling theoretical framework was lacking. Competing candidates for such a frame-

work, however, were being developed independently using different versions of game

theory as their models of coalition formation: the Laver–Shepsle model and Baron’s

sequential bargaining models.

3 Structure-induced Equilibrium:

The Laver–Shepsle Model

.............................................................................

In his seminal paper Shepsle (1979) formally introduced institutional structure as a

committee system. The key idea was to assume additional constraints in the spatial

decision-making environments. Specifically, Shepsle assumed that each legislator is

assigned to exactly one issue. This assignment can be interpreted as a committee

system in the context of the US Congress. Intuitively, a committee has exclusive

jurisdiction on a given issue. Using a result by Kramer (1972), it can easily be shown

that structure-induced equilibria exist for every committee assignment.

8

The basic

idea is to have the committees vote sequentially on each issue separately. Since each

issue corresponds to a single-dimensional policy space, the median voter theorem

guarantees that a core exists on that dimension. The final outcome then is the

composite of the sequence of committee decisions. The key methodological idea of

⁶ See Diermeier and Merlo 2000 for a critical discussion of Strom’s theory of minority cabinets.

⁷ For a detailed discussion of the cabinet termination literature see Laver 2003. Laver also discusses

alternative conceptualization of the lifespan of governments, such as party turnover (e.g. Mershon 1996).

⁸ For a thorough formal analysis see e.g. Austen-Smith and Banks 2005.

166 coalition government

SIE theory thus consists in transforming a social choice problem in which the core

does not exist (multidimensional choice spaces) into a more structured problem in

which the core (as the issue-by-issue core) does exist. Formally, issue-by-issue voting

corresponds to an agenda restriction, since in later states of the process decisions on

earlier dimensions cannot be revisited. What made this particular agenda restriction

plausible is that it corresponded well to features of real legislative decision-making

such as a committee system.

Laver and Shepsle (1990) apply this methodology to the study of cabinets. In

the context of coalitional government, however, the key decision-makers are not

committees and individual legislators, but cabinets and parties. Laver and Shepsle

thus interpret the issue assignments from Shepsle (1979) as cabinet portfolios assigned

to parties. Holders of portfolios can unilaterally determine the policy choice on that

dimension.

Going beyond the original SIE analysis, Laver and Shepsle then ask under what

circumstances such portfolio assignments are in the majority core of a voting game

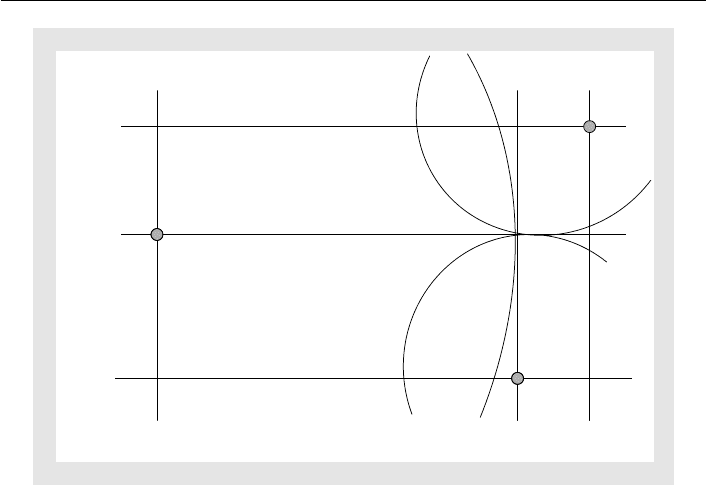

on cabinet assignments. Consider the example in Figure 9.1.

9

In this example there

are three parties A, B, and C with their ideological positions along two policy dimen-

sions represented by small circles. Each combination of letters represents a possible

coalition government. Suppose that every two-party coalition represents a majority,

while each single-party government is a minority government. The idea of their

model is that it takes a government (modeled as an allocation of portfolios) to beat a

government. Government BA, for example, is stable because there is no alternative

government in its win set even though there are policies strictly preferred to the

policy implemented by BA. But according to Laver and Shepsle’s model these policies

do not constitute credible alternatives to BA since they cannot be implemented by

any government. As in the case of congressional committee systems discussed above,

the Laver–Shepsle results therefore depend on an agenda restriction. The twin as-

sumption is that in a parliamentary system policies are decided in cabinets, not by

the legislature and that each minister effectively can exercise dictatorial control over his

respective portfolio dimension.

Laver and Shepsle show not only that portfolio assignments can be stable, but

that the stable assignments may be of the minority type. Finally, by perturbing the

key parameters of the equilibrium governments, Laver and Shepsle also hint at an

explanation for cabinet stability.

10

With one model, so it seems, Laver and Shepsle succeeded in addressing all the

major empirical themes discussed above. Moreover, their methodology also promised

to shed some new light on the old question of which specific cabinet would form. The

appeal of the Laver–Shepsle model is that it maintains the basic features of spatial,

institution-free models, but seems to add just enough structure to account for the

new empirical challenges.

⁹ Adapted from Laver and Shepsle 1990, 875.

¹⁰ See Laver and Shepsle 1994, 1996 for rich analyses of various institutional features of government

formation and termination using their framework. Laver and Shepsle 1998 model cabinet stability using

random perturbations.

daniel diermeier 167

AB

A

AC

B

BA

BC C

CA

CB

Y

Dimension

X

Dimension

Fig. 9.1 Ideal points and win-sets of credible proposals

As in the case of Shepsle’s model for the US Congress, the explanatory power of

the Laver–Shepsle model depends on the empirical plausibility of its key assumption

about cabinet decision-making. The results, for example, do not go through in a

model where ruling parties bargain over policies in cabinets.

11

But there is a more

serious, methodological problem with the model. This problem has nothing to do

with the plausibility of any of the assumptions, but with the solution concept used by

Laver and Shepsle.

This problem, ironically, was pointed out by Austen-Smith and Banks (1990)ina

paper in the same issue of the American Political Science Review where the Laver–

Shepsle article was published. Austen-Smith and Banks show that except in the

very special case of three parties, two dimensions, and Euclidean (“circular”) pref-

erences, structure-induced equilibria in the portfolio assignment game may not exist.

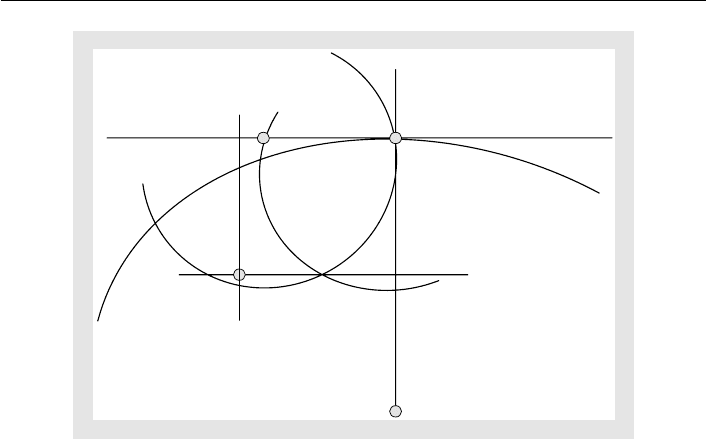

Figure 9.2 (adapted from figure 5 in Austen-Smith and Banks 1990) demonstrates this

point. In this example there is one large party, D, with 49 per cent of the vote share

and three smaller parties with a vote share of 17 per cent each. Note that parties D and

C each prefer cabinet D to cabinets A, B, and AB, while parties A, B, C, which jointly

constitute a majority, prefer B to D. Finally, A and D prefer D over C. Therefore, the

core of cabinet assignment problem is empty.

The methodological problems uncovered by Austen-Smith and Banks consist in

the insight that core existence in the Laver–Shepsle model cannot be guaranteed. Note

that in cases of an empty core the Laver–Shepsle theory has no empirical content; it

does not predict anything. Put differently, the agenda restrictions considered by Laver

¹¹ See the next two sections for such models.

168 coalition government

D

C

B

A

AB

BC

Fig. 9.2 Core-existence cannot be extended to more than three parties

and Shepsle are not sufficienttoavoidthewell-knowncorenon-existenceproblems

(Plott 1967).

Elsewhere (e.g. Diermeier 1997; Diermeier and Krehbiel 2003) I have argued that

the root cause of these problems lies in the use of the core as a solution concept

while non-cooperative game theory (with Nash equilibrium as its solution concept)

does not suffer similar problems. One could, for example, reformulate the Laver–

Shepsle framework as a non-cooperative bargaining model among party leaders.

The theoretical literature on coalition government, however, has not taken this path.

Rather, a whole variety of alternative frameworks, all based on non-cooperative game

theory, have been proposed over the last fifteen years. It is to those applications of

non-cooperative game theory that we turn next.

4 Sequential Bargaining:The

Baron–Ferejohn Model

.............................................................................

The Baron–Ferejohn (“BF”) model of legislative bargaining (Baron and Ferejohn

1989) is one of the most widely used formal frameworks in the study of legislative

politics. One of the first direct applications of the model to a specific problem in

political science was the problem of government formation (e.g. Baron 1989, 1991).

In all variants of the BF model, a proposer is selected according to a known rule.

He then proposes a policy or an allocation of benefits to a group of voters. According

to a given voting rule, the proposal is either accepted or rejected. If the proposal is

daniel diermeier 169

accepted, the game ends and all actors receive payoffsasspecifiedbytheaccepted

proposal. Otherwise, another proposer is selected, etc.

12

The process continues until

a proposal is accepted or the game ends.

Consider a simple version of the model where there are three political parties with

no party having a majority of the votes in the legislature. The BF model predicts that

the party with proposal power will propose a minimal winning coalition consisting

of him- or herself and one other member, leaving the third party with a zero payoff.

The proposing party will give a proposed coalition partner just the amount necessary

to secure an acceptance. This amount (or continuation value) equals the coalition

partner’s expected payoff if the proposal is rejected and the bargaining continues.

Proposals are thus always accepted in the first round. Note that the proposing party

maximizes its payoff by choosing as a coalition partner one of the parties with the

lowest continuation value. The division of spoils will in general be highly unequal,

especially if the parties are very impatient.

Consider a simple, two-period, example of the model where three parties divide $1.

If the money is not divided after two periods, each party receives nothing. Suppose

further that each party has an equal amount of seats and that in each period the

probability that any given party is chosen as the proposer is proportional to seat

share, i.e. each party is selected with probability 1/3. In the last period each recognized

proposer will propose to keep the entire $1 and allocate nothing to the other two

parties. This proposal will be accepted by the other parties.

13

Now consider each

party’s voting decision in period one. If the proposal is rejected, each party again

has a probability of 1/3 of being selected as proposer in the second period. But as we

just showed, in that case the proposer will get the entire $1. Therefore, the expected

payoff from rejecting a proposal is 1/3 for each party. This expected payoff is also called

the “continuation value.” Call it D

i

for each party I (here D

i

=1/3 for each i). Now

consider the incentives of a proposer in period one. By the same argument as above

14

each proposer will make a proposal that allocates $1 − D

i

(here $2/3) to himself, D

i

to one other party (his “coalition partner”), and nothing to the remaining party. This

proposal will be accepted.

15

¹² A variant of this set-up allows (nested) amendments to a proposal before it is voted on. This is the

case of an open amendment rule (Baron and Ferejohn 1989).

¹³ Why would the non-proposing parties vote for a proposal where they receive nothing? The idea is

the following. Since the model assumes that all parties’ relevant motivations are fully captured by their

monetary rewards, parties would accept any ε-amount for sure. But then the proposer can make this ε as

small as he wishes. The technical reason is that a proposal that allocates everything to the proposer is the

only subgame perfect Nash equilibrium in the second period. From the proposer’s point of view offering

ε more than $0 cannot be optimal since he can always offer less than ε. From the other parties’ points of

view accepting $0 with probability one is optimal (they are indifferent), but voting to accept with any

probability less than one cannot be optimal, since in that case the proposer would be better off offering

some small ε which the parties would accept for sure.

¹⁴ See also the previous footnote.

¹⁵ In their general model, Baron and Ferejohn show that an analogous argument also holds if the

game is of potentially infinite duration. That is, parties are selected to propose until agreement is

reached. To ensure equilibrium existence future payoffs need to be discounted. The more they are

discounted, i.e. the more impatient the parties, the higher the payoff to the proposer. In subsequent years

Baron systematically applied the model to various aspects of government formation such as different

170 coalition government

Compared to the Laver–Shepsle model, the Baron–Ferejohn model has many

methodological advantages. Because of the use of non-cooperative game theory,

equilibrium existence is assured even in environments (e.g. dividing a fixed benefit

under majority rule) where the core is empty.

16

These features make the model very suitable for institutional analysis.

However, compared to the Laver–Shepsle model, the Baron–Ferejohn model is

much more difficult to work with, especially if one leaves the purely distributive

(“divide-the-dollar”) environment and includes policy preferences. In that case only

the simplest environment of three symmetric parties with Euclidean preferences is

reasonably manageable.

17

Also, the model is only about coalition formation, not

stability.

Therefore, even though the Baron–Ferejohn model does not have the same

methodological challenges as the Laver–Shepsle model, its applicability in the study of

coalition government is constrained by its technical difficulties. These shortcomings

have limited its use in explaining, for instance, minority government formation or

cabinet stability.

18

5 Alternative Frameworks:

Demand Bargaining and

Efficient Negotiations

.............................................................................

The methodological shortcomings of the Laver–Shepsle framework and the techni-

cal challenges of using the Baron–Ferejohn model in an environment with policy

preferences have led to a search for alternative bargaining models over coalition

governments. Two candidates have received the most interest: demand bargaining

and efficient negotiations.

voting and proposal rules (Baron 1989), parties with spatial preferences (Baron 1993), and multistage

decision-making (Baron 1996). See Baron 1993 for a detailed overview.

¹⁶ The curious reader may ask why the Baron–Ferejohn model does not face the same

methodological issues as the Laver–Shepsle model. Suppose parties would vote over selection

probabilities. Don’t we face similar non-existence problems as discussed in the Laver–Shepsle model?

Such a question confuses two different methodologies. Laver and Shepsle use the core as their solution

concept. If we use the core, non-existence problems reappear at the level of institutional choice. But if

we use Nash equilibrium, then the collective choice over selection probabilities again needs to be

modeled as a non-cooperative game and this game generally will have a Nash equilibrium. For a more

detailed discussion of this subtle point see Diermeier 1997; Diermeier and Krehbiel 2003. For a model of

voting over proposal rights see Diermeier and Vlaicu 2005.

¹⁷ See Austen-Smith and Banks 2005 and Banks and Duggan 2000, 2003, for a thorough analysis of

the Baron–Ferejohn model. In the general case of convex preferences we also have to worry about

multiple equilibria. See also Eraslan and Merlo 2002.

¹⁸ See, however, Baron 1998 who proposed a model based on Diermeier and Feddersen 1998 where

minority governments could be stable, but would not be chosen in equilibrium. See also Kalandrakis

2004.

daniel diermeier 171

The demand bargaining approach in the study of coalition government is due

to Morelli (1999). In Morelli’s approach agents do not make sequential offers (as in

the Baron–Ferejohn model), but make sequential demands, i.e. compensations for

their participation in a given coalition. Specifically, the head of state chooses the first

mover. After that, agents make sequential demands until every member has made

a demand or until a majority coalition forms. If no acceptable coalition emerges

after all players have made a demand, a new first demander is randomly selected;

all the previous demands are void, and the game proceeds until a compatible set of

demands is made by a majority coalition. The order of play is randomly determined

from among those who have not yet made a demand, with proportional recognition

probabilities.

19

To see the difference from the Baron–Ferejohn model consider the three-party

example as above. Morelli (1999,proposition1) shows that in this case the distrib-

ution of benefits is ($1/2,$1/2) among some two-party coalition. In contrast to the

Baron–Ferejohn model there is no proposer premium. Intuitively, each party has the

same bargaining power in the demand bargaining game and that is reflected in

the equilibrium outcome.

An alternative approach was proposed by Merlo (1997) based on the work of Merlo

and Wilson (1995). As in the original Baron–Ferejohn model and in Morelli’s model,

a set of players bargain over a perfectly divisible payoff by being recognized and

then making offers. If the offer is accepted by all parties, the government forms; if

not, bargaining continues. However, there are two key differences. First, all players

need to agree to a proposed distribution. Second, the value of the prize changes

over time. Merlo interprets this change as shifting common expectations about the

lifespan of the chosen coalition caused, for example, by shifting economic indicators

(e.g. Warwick 1994). Merlo and Wilson (1995, 1998) show that this game has a unique

stationary subgame perfect equilibrium.

20

Second, the equilibrium of the bargaining

game satisfies the so-called separation principle:anyequilibriumpayoff vector must

be Pareto efficient, and the set of states where parties agree must be independent

of the proposer’s identity. A very rough intuition for the result is that because all

members of the coalition need to agree to an allocation, the coalition behaves as if

it desired to maximize the joint payoff.Withchangingpayoffs this implies that for

some states the parties would be better off to delay agreement to wait for a better

draw. Therefore, bargaining delays can occur in equilibrium.

21

In contrast to earlier

accounts (e.g. Strom 1988) that had interpreted long formation times as evidence of

a crisis, Merlo and Wilson showed that delays may be optimal from the point of view

of the bargaining parties. By not agreeing immediately (and thus forgoing a higher

¹⁹ Earlier models of demand bargaining used an exogenous order of play. See e.g. Selten 1992;Winter

1994a, 1994b.

²⁰ Both unanimity and randomly changing payoffs are important for both the uniqueness result and

the efficiency property (Binmore 1986; Eraslan and Merlo 2002). Majority rule, for example, leads to

multiple equilibria and inefficiency. Parties agree “too early” to ensure that they will be included in the

final deal.

²¹ For an empirical studies of the cabinet formation processes see Diermeier and van Roozendaal

1998; Diermeier and Merlo 2000; Martin and Vanberg 2003.