Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

236 Freedom Riders

defied the logic of their precarious position. Even in the face of tear gas and

surging rioters, freedom songs reverberated through the sanctuary. Earlier

the mood had dictated the singing of traditional hymns of hope and praise,

But now the hymns were interspersed with the “music of the movement”—

songs such as “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ’Round” and “We Shall

Overcome.” In some cases the Freedom Riders themselves led the sing-

ing, as the fear of being arrested was overwhelmed by the emotion of the

moment. Like most of those who had mustered the courage to attend the

rally, they believed that it was time to stand up and be counted, whatever the

consequences.

30

To Federal authorities, few of whom shared the Riders’ faith in direct

action, the consequences of standing up for freedom in a Montgomery church

seemed very grave indeed. By 9:30, with the crisis at First Baptist showing no

signs of letting up, Justice Department officials were preparing for the worst.

After releasing a public statement urging “all citizens of Alabama and all

travelers in Alabama to consider their actions carefully and to refrain from

doing anything which will cause increased tension or provoke violence or

resistance,” Robert Kennedy began to contemplate the previously unthink-

able. Moved by the force of his own words, he asked the Pentagon to place

army units at Fort Benning, ninety-five miles east of Montgomery, on high

alert. The troops would only be used as a last resort, he assured White, but

the inability of the marshals to disperse the mob and the lack of response

from state officials left the federal government with few options.

Unbeknownst to Kennedy and White, Patterson, with the help of a

Maxwell telephone operator, was listening in on this and other Justice De-

partment conversations. Officially, though, Patterson was out of the loop.

After several futile attempts to contact the governor, Kennedy and White

turned to Floyd Mann as the only reachable—and reasonable—state official.

A native of Alexander City, Alabama, Mann considered himself a segrega-

tionist, but not to the point of countenancing violence or disrespect for the

Constitution or the law. “He was Southern,” Bernard Lafayette recalled years

later, “but I don’t think he had the same kind of passion for preserving segre-

gation at any cost as some of his colleagues. I think he was . . . caught in a

system where he had to perform certain duties, but he wanted to do it in the

most humane way.” Although there was little Mann could do without firm

authorization from Patterson, he took it upon himself to urge White to send

in additional marshals. White, interpreting this request as the first indication

that state officials were beginning to recognize the seriousness of the situa-

tion, offered to place the marshals already on the scene at Mann’s disposal,

but he had to confess that he had no additional marshals in reserve. This

admission was not what Mann wanted to hear, although, as he later admitted,

he secretly hoped that the marshals’ weakness would force Patterson’s hand.

31

Meanwhile, the violence in the streets around First Baptist was intensi-

fying. Marshals were being attacked by brick-throwing rioters, and some of

If You Miss Me from the Back of the Bus 237

the federal peacekeepers were too scared to get out of their vehicles. There

were reports of guns being fired randomly into black homes in the vicinity of

the church, and a Molotov cocktail had nearly set the church roof on fire.

Gangs of marauding whites were roaming the streets at will and appeared to

be converging on the church for a massive, coordinated assault. At one point

things looked so bleak that Abernathy and King suggested that they and the

other high-profile ministers should consider surrendering themselves to the

mob in order to save the men, women, and children in the sanctuary. No one

was quite sure whether King and Abernathy were serious, and Walker later

confessed that his first thought was that King had lost touch with reality, but

for a few moments there was a soul-searching silence as the leaders contem-

plated the advisability of sacrificial redemption. Shuttlesworth, in character-

istically impulsive fashion, cut through the tension with a straightforward “If

that’s what we have to do, let’s do it.” But no one actually moved toward the

door. Fortunately, events beyond the ministers’ control soon rendered mar-

tyrdom unnecessary.

After McShane informed White that he was not sure that his marshals

could hold out much longer, the bad news was relayed to the attorney general,

who finally had heard enough. Following a brief consultation with Marshall,

he decided to ask the president to sign a proclamation authorizing the imme-

diate deployment of the soldiers at Fort Benning. As it turned out, however,

the attorney general was not the only one who had heard enough. While

Justice Department staff members puzzled over the logistics of acquiring the

vacationing president’s signature (he was a helicopter ride away in northern

Virginia), Patterson, who had been eavesdropping on the phone communi-

cations between Washington and White’s office at Maxwell Field, decided to

act. At ten o’clock, he placed the city of Montgomery under what he called

“qualified martial rule.” Almost immediately, a swarm of city policemen rushed

down Ripley Street, closely followed by fifteen helmeted members of the

Alabama National Guard. Within five minutes, more than a hundred Guards-

men had formed a protective shield in front of the church. By that time, the

police, with Commissioner Sullivan making a show of his authority, had cleared

the immediate area of rioters. Nearby a greatly relieved McShane, with White’s

approval, offered to place his marshals under the command of the National

Guard. Accepting McShane’s offer, the colonel in charge of the Guardsmen

promptly ordered the marshals to leave the scene. As the overall commander

of the Guard, Adjutant General Henry Graham announced a few minutes later

that the sovereign state of Alabama had everything under control and needed

no further help from federal authorities.

32

In actuality, dispersing the mob proved more difficult than Graham or

anyone else had anticipated. While the worst of the mayhem was over by 10:15,

sporadic violence continued for several hours. Indeed, for the besieged gather-

ing inside the sanctuary the joyous news of the soldiers’ arrival was soon tem-

pered by the realization that their rescuers were Alabama segregationists, not

238 Freedom Riders

federal troops. This disappointment did not stop them from proceeding with

the mass meeting, however. Despite lingering fumes and frazzled nerves,

the celebration of freedom went forward almost as if nothing had happened.

As several of the reporters covering the rally—and the Freedom Riders

themselves—later remarked, the spirit inside the sanctuary was difficult to

explain to anyone who was not there. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen a group of

people band together as the crowd did in the church that night,” Nash mar-

veled, during a conference on “The New Negro” a few weeks later. The

soulful music, the presence of the Freedom Riders and so many other move-

ment veterans, the sight of women and children sitting amid broken glass, the

soaring rhetoric from the pulpit—everything conspired to create an emotion-

filled experience.

King and others did not mince words that evening. As the television

cameras whirred, one speaker after another juxtaposed praise for the Free-

dom Riders with condemnation of the state and local authorities who had

incited a week of lawlessness. After urging the audience to launch “a full scale

nonviolent assault on the system of segregation in Alabama,” King insisted

that “the law may not be able to make a man love me, but it can keep him

from lynching me. . . . Unless the federal government acts forthrightly in the

South to assure every citizen his constitutional rights, we will be plunged

into a dark abyss of chaos.” Departing from his prepared text, he placed much

of the blame on Patterson, who bore the “ultimate responsibility for the hid-

eous action in Alabama.” “His consistent preaching of defiance of the law,”

King claimed, “his vitriolic public pronouncements, and his irresponsible

actions created the atmosphere in which violence could thrive. Alabama has

sunk to a level of barbarity comparable to the tragic days of Hitler’s Ger-

many.” Shuttlesworth agreed. “It’s a sin and a shame before God,” he de-

clared, “that these people who govern us would let things come to such a sad

state. But God is not dead. The most guilty man in this state tonight is Gov-

ernor Patterson.” For nearly two hours expressions of outrage alternated with

impassioned calls for continued struggle and sacrifice until everyone in the

sanctuary, as Farmer put it, “was ready at that moment to board buses and

ride into the Promised Land.” Following a final hymn and an emotional bene-

diction, the exhausted preachers dismissed the congregation a few minutes

before midnight.

33

Despite some concern about what they would encounter outside the

church, most of the audience wasted no time in heading for the exits. Some

had been in the sanctuary since late afternoon, and even those who had ar-

rived late were eager to get home to reassure friends and family that they

were safe. To their surprise, however, the exits were blocked by National

Guardsmen with drawn bayonets. The only person allowed outside the church

was King, who demanded an explanation from General Graham. Moments

earlier Graham had received word that Robert Kennedy had officially sanc-

tioned the placing of federal marshals under state control, and he was in no

If You Miss Me from the Back of the Bus 239

mood to relinquish any of his expanded authority, especially to a meddling

black preacher from Georgia. An arch-segregationist who worked as a Bir-

mingham real estate agent in his civilian life, Graham turned a deaf ear to

King’s appeal for compassion. Some members of the congregation were at

the breaking point and desperately needed to go home, King explained. But

Graham would not relent, insisting that the situation outside the church was

too unstable. Though disappointed, King urged Graham to deliver this mes-

sage directly to the men and women inside the sanctuary. After some hesita-

tion, he agreed.

Marching into the church with several of his aides, Graham presided

over a formal reading of Patterson’s declaration of martial law, which pre-

dictably began with the hostile phrase “Whereas, as a result of outside agita-

tors coming into Alabama to violate our laws and customs.” Farther down,

the proclamation claimed that the federal government had “by its actions

encouraged these agitators to come into Alabama to foment disorders and

breaches of the peace.” As a murmur of indignation spread through the sanc-

tuary, Graham stepped forward to inform the crowd that the siege was not

over, that in all likelihood they would have to remain in the church and un-

der the protection of the National Guard until morning. Technically it was

already morning, but the meaning of his words was clear: Liberation had

turned into protective custody.

To the Freedom Riders, who had already experienced the protective

custody provided by Bull Connor, the scene was all too familiar. “Those

soldiers didn’t look like protectors now,” Lewis later commented. “Their

rifles were pointed our way.

They looked like the enemy.”

From the perspective of those

in the sanctuary, martial law

looked a lot like continued in-

timidation and harassment, es-

pecially after they realized that

the forces surrounding the

church were all controlled by

Patterson, a governor who had

branded the Freedom Riders as

outlaws. King, in particular, felt

betrayed by the federal gov-

ernment’s apparent abdication

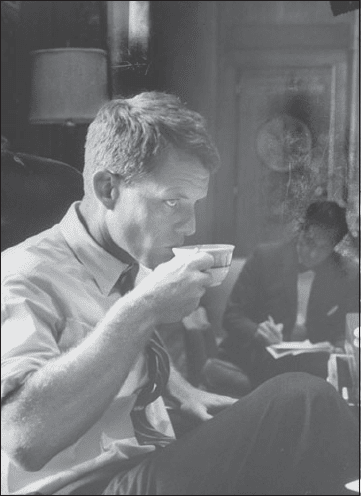

Attorney General Robert F.

Kennedy awaits the resolution

of the church siege in Mont-

gomery, Sunday evening, May

21, 1961. (Getty Photos)

240 Freedom Riders

of authority. In a fit of anger, he called Robert Kennedy to complain, but

Kennedy, who had just come from an upbeat interview with a magazine re-

porter, was not interested in listening to King’s lament. “Now, Reverend,”

he retorted, “don’t tell me that. You know just as well as I do that if it hadn’t

been for the United States marshals, you’d be as dead as Kelsey’s nuts right

now!” The allusion to Kelsey’s nuts—an old Boston Irish aphorism—meant

nothing to King, but the tone of Kennedy’s voice gave him pause. Before

hanging up, King handed the phone to Shuttlesworth, who echoed his

colleague’s complaint about the marshals’ withdrawal. Kennedy would have

none of it. “You look after your end, Reverend, and I’ll look after mine,” he

scolded. Clearly, on this night at least, the attorney general had done about

all that he was going to do on behalf of the Freedom Riders. As King and

Shuttlesworth explained to Seay a few moments later, they now had no choice

but to make the best of a bad situation.

34

While King and others reluctantly turned First Baptist into a makeshift

dormitory, the National Guard, aided by Sullivan’s police and Mann’s high-

way patrolmen, conducted a mopping-up operation in the surrounding streets.

By this time almost all of the marshals had returned to Maxwell Field, leav-

ing the downtown battleground in the hands of state and local forces. After

Graham assured Patterson that everything was under control, the formerly

recalcitrant governor called Robert Kennedy to vent his anger. Patterson’s

tone was abusive from the start, as the pent-up hostilities and emotions of

the past week burst forth. “Now you’ve got what you want,” Patterson liter-

ally shouted over the phone. “You got yourself a fight. And you’ve got the

National Guard called out, and martial law, and that’s what you wanted. We’ll

take charge of it now with the troops, and you can get out and leave it alone.”

Kennedy protested that he had only sent in the marshals reluctantly after

state and local officials had abrogated their responsibilities, but Patterson

refused to accept this or any other explanation that let the federal govern-

ment off the hook.

Later in the conversation Kennedy tried to get beyond recriminations

by quizzing Patterson about his plans to evacuate First Baptist, but when he

asked specifically if the governor and the National Guard could guarantee

the safety of the Freedom Riders and their hosts once they left the church, he

did not get the answer he was looking for. The state could offer a guarantee

to everyone but King, Patterson declared. Stunned, Kennedy shot back: “I

don’t believe that. Have General Graham call me. I want to hear a general of

the United States Army say he can’t protect Martin Luther King.” Patterson

later explained his reticence to protect King as a simple matter of common

sense. Kennedy, he complained, “really didn’t understand the problem. . . .

When you’ve got a man running all over this town that will not do what you

say, and people all over town wanting to kill him, how can you personally

guarantee that man’s protection?” At the time, however, Patterson freely

admitted to Kennedy that his decision was largely a matter of political sur-

If You Miss Me from the Back of the Bus 241

vival, a confession that drew little sympathy. “John,” Kennedy responded,

“it’s more important that these people in the church survive physically than

for us to survive politically.” To Patterson, this final insult was too much to

bear, and the conversation ended in a curt exchange of strained salutations.

35

It was now one o’clock in the morning, and back at First Baptist the

exhausted congregation was reluctantly settling in for the night. Some were

still lined up to use the church’s only phone, but most had sprawled out

among the pews in an attempt to get some sleep. As Frank Holloway, a SNCC

volunteer from Atlanta, described the scene, there “were three or four times

as many people as the church was supposed to hold, and it was very hot and

uncomfortable. Some people were trying to sleep, but there was hardly

room for anybody to turn around. Dr. King, other leaders, and the Free-

dom Riders were circulating through the church talking to people and try-

ing to keep their spirits up.” Fortunately, there was room in the basement

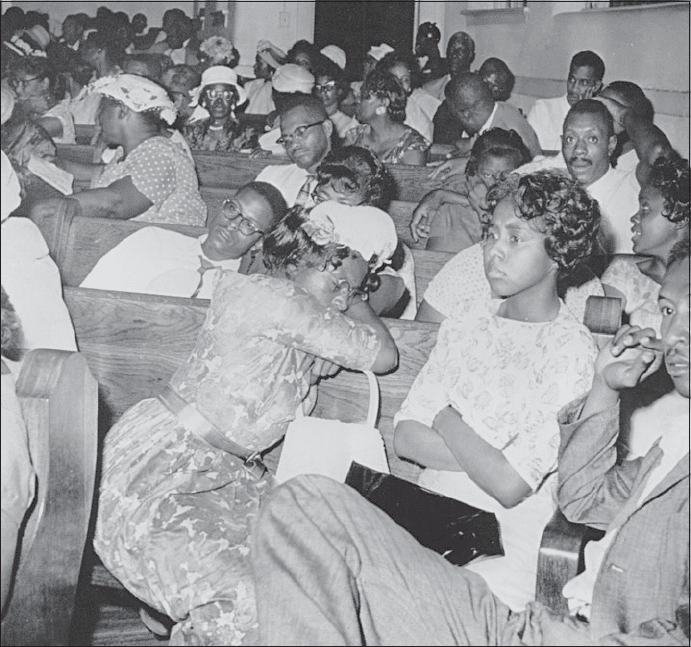

In the early hours of Monday morning, May 22, 1961, the pews of Montgomery’s

First Baptist Church were transformed into a makeshift dormitory. (Courtesy of

the Nashville Tennessean and AP Wide World)

242 Freedom Riders

to accommodate the children, and most of the reporters had already slipped

out of the church to file their stories, but the air inside the sanctuary, still

smelling of tear gas, made the quarters seem even tighter than they actually

were. Even so, many inside the church were grateful to be alive, having sur-

vived what Jessica Mitford called “the most terrifying evening of my life.”

Adding to the terror was the sullen presence of Graham and the Na-

tional Guardsmen—many of whom made no secret of their contempt for the

outside agitators who had provoked the Montgomery crisis—and the gnaw-

ing uncertainty about what was going on outside the church. As the long

night of protective custody stretched on, the gathering at First Baptist was

kept in the dark literally and figuratively about the implications of state au-

thority. Only later did they learn that White and other Justice Department

officials were engaged in frantic behind-the-scenes negotiations with the

National Guard to end the siege once and for all. By four o’clock White’s

growing frustration with Graham had prompted him to send William Orrick

to the National Guard armory to see what could be done to get the church

evacuated sometime before dawn. What followed was an almost surreal com-

bination of Southern Gothic and Cold War drama. As Orrick recalled the

scene: “I was treated like I might have been treated in Russia and taken over

to Dixie division . . . where there wasn’t a sign of an American flag . . . just the

Confederate flags.”

After being escorted to Graham’s office, Orrick declared that he had

been sent by the Justice Department to “negotiate” a timely evacuation of

First Baptist. “We want to know whether your troops are going to leave that

church and let the people go home,” Orrick explained, “and whether they’re

going to keep the peace here tomorrow.” Busy polishing his boots, Graham

raised his eyes slowly and grunted: “Well, I’m not about to decide either

matter.” When Orrick pressed him further, Graham claimed he couldn’t make

any commitments without talking to the governor first. Only after an ex-

asperated Orrick threatened to send the marshals back to the church did

Graham begin to come around. Despite the suspicion that Orrick was bluff-

ing and speaking without clear authority, Graham eventually agreed to begin

the evacuation as soon as he could arrange a proper escort. Within minutes a

convoy of National Guard trucks and jeeps pulled up in front of the church,

and over the next hour the Freedom Riders and the faithful parishioners of

First Baptist finally left the scene of a confrontation that none of them would

ever forget.

36

BY THAT TIME THE MORNING NEWSPAPERS were already hitting the streets of

New York and other Eastern cities, as the nation awoke to the news that

Montgomery had once again been plunged into chaos. To the relief of both

federal and state officials, most of the initial press coverage gave the impres-

sion that, as bad as it was, the situation in Montgomery could have been

much worse. Despite the threat of mass violence, the damage to persons and

If You Miss Me from the Back of the Bus 243

property apparently had been kept to a minimum. Accounts differed as to the

relative contributions of federal, state, and local law enforcement, with con-

servative and Southern papers emphasizing the latter two, but the dominant

story line was cooperation. Faced with an unfortunate confrontation between

militant civil rights activists and white supremacist vigilantes, federal, state,

and local authorities reportedly had put aside their differences in the interest

of restoring civil order. Even a New York Times editorial that excoriated

Patterson for encouraging mob violence went on to express the opinion that

“the Constitutional issue between the Federal and the state authorities may

have actually reached its climax yesterday and may already be moving toward

a solution.” Interestingly enough, the Times editorial also tried to strike a

delicate balance between defending the Freedom Riders’ constitutional rights

and warning about the dangers of provocative agitation. “The issue in Mont-

gomery,” the editors insisted, “. . . is the right of American citizens, white

and Negro alike, to travel in safety in interstate commerce, without being

segregated in contravention of the Constitution. This right is now being

tested by the so-called ‘Freedom Riders,’ a racially mixed group consisting

primarily of students, who are waging their campaign for civil rights in the

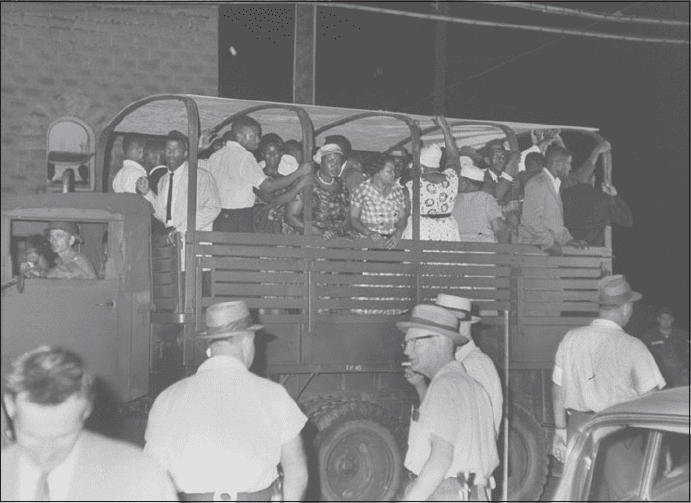

The evacuation of parishioners and Freedom Riders from Montgomery’s First

Baptist Church by the Alabama National Guard, Monday morning, May 22,

1961. The men wearing armbands and straw hats are federal marshals. The three

evacuees on the far left are (left to right) Bill Harbour, John Lewis, and Joseph

Carter. (Getty Photos)

244 Freedom Riders

South in a Gandhian spirit of idealism and of non-violent resistance to an

evil tradition. But it is also being waged with loud advance publicity and in

deliberate defiance of state laws and local customs. There can be no question

that in the Freedom Riders’ completely legal action there is an element of

incitement and provocation in regions of high racial tension.”

This tenuous endorsement reinforced the Kennedy administration’s pre-

ferred position on the Freedom Ride, sanctioning the legality but not the

advisability of forcing the issue of desegregated transit. On Monday morn-

ing, however, administration spokesmen did their best to push this vexing

inconsistency—along with the Freedom Riders themselves—into the back-

ground. Political damage control called for an uplifting cover story of inter-

governmental harmony that downplayed the specter of constitutional crisis.

White and others denied that the administration had been on the verge of

sending in the army, and Robert Kennedy made a point of praising Floyd

Mann as an exemplary law enforcement officer who put professionalism ahead

of personal interest. If there was a villain in the official account of the Mont-

gomery crisis—other than the mob itself—it was Patterson, but even he got

off fairly lightly considering the hard feelings of the night before. While still

angry at Patterson for flouting federal authority, Kennedy did not want to

provoke another war of words with a member of his own party. The admin-

istration was already on shaky political ground in the Deep South, and turn-

ing Patterson into another Orval Faubus would only make matters worse.

37

As expected, Patterson wasted no time in putting his own spin on the

events of May 21. Though relatively unconcerned about the national and

international reactions to the crisis, he was determined to protect his politi-

cal reputation among white Southerners. At a carefully staged Monday morn-

ing press conference, he took full credit for his dual defense of segregation

and state sovereignty. Pointing to a stack of telegrams that endorsed his ac-

tions and condemned the meddling Freedom Riders and their federal ac-

complices, he defiantly contradicted the claim that federal and state authorities

were working in harmony. The deployment of the marshals was an affront to

the principle of states’ rights and to Alabama’s proud tradition of capable law

enforcement. The marshals were no more welcome in Alabama than the Free-

dom Riders, he insisted, and the sooner they left the state the better. Other

state officials, including Attorney General Gallion and the entire Alabama

congressional delegation, promptly echoed Patterson’s call for an immediate

withdrawal of the marshals. By early afternoon an emergency meeting of thirty

business and professional leaders convened by Montgomery mayor Earl James

had approved a resolution calling the marshals’ presence “more inflammatory

than tranquilizing,” and as the day wore on white public opinion in the state

seemed to be lining up behind the governor’s anti-federal position.

There were, however, several notable exceptions. Former governor Jim

Folsom phoned Robert Kennedy to express his support for the marshals’

deployment, and the Alabama Press Association, meeting in Tuscaloosa, while

If You Miss Me from the Back of the Bus 245

taking no explicit stand on the marshals or the Freedom Rides, had already

passed a resolution attributing the “breakdown of civilized rule” on Saturday

to “the failure on the part of law enforcement officers in parts of Alabama to

provide protection to and insure basic freedom to citizens in general and to

newspaper, wire service, radio, and television representatives in particular.”

Grover Hall Jr., the editor of the Montgomery Advertiser, spoke for many of

the state’s journalists when he questioned Patterson’s leadership in a biting

Monday morning editorial. “Patterson started out by saying that he would

not nursemaid the agitators and he might arrest the U. S. marshals,” Hall

reminded his readers. “But before it was over Patterson was baby-sitting the

agitators all night in a church and the highway patrol was working in harness

with the federal troops.” While Hall had little sympathy for either the Free-

dom Riders or the federal government, he could not resist asking why the

crisis had occurred in Alabama and not elsewhere. In the days ahead, this nag-

ging question would spell political trouble for Patterson and other Alabama

officials who found themselves riding an unpredictable wave of reaction.

38

For federal officials the public mood in Alabama was only one of several

unpredictable factors complicating the situation in the immediate aftermath

of the Sunday night siege. Despite Judge Johnson’s temporary restraining

order, the legal position of the Freedom Riders remained in doubt. Under

martial law the warrants issued by Judge Jones had been turned over to Colo-

nel Herman Price of the Alabama National Guard, but as yet Price had made

no arrests. During a tense afternoon press conference at Maxwell Field, White

deflected questions about the Freedom Riders’ whereabouts and denied that

federal officials were working in close cooperation with local “Negro groups

or Negro leaders.” Indeed, he indicated that federal marshals would not in-

tervene if local or state authorities attempted to arrest the Freedom Riders.

“That would be a matter between the Freedom Riders and local officials,” he

insisted, adding: “I’m sure they would be represented by competent coun-

sel.” White also tried to reassure the reporters that the decision to deploy

two hundred additional marshals earlier in the day was a simple logistical

maneuver aimed at replacing “men who are headed home for various rea-

sons.” “Our present intentions are to remain here for a few days,” he de-

clared. If additional trouble arose, federal authorities would “take cooperative

action” with General Graham and the National Guard, but the marshals had

“no desire to push aside local officers.” When asked if federal authorities

planned to prosecute any of the rioters, White hedged, explaining that “if we

can turn up evidence that any Federal violations have been committed, we

will make some arrests.” Still, the overall message was one of conciliation

and deference to local sensibilities.

39

White’s statement to the press reflected the administration’s growing

misgivings about the decision to use federal marshals to protect the Freedom

Riders. Earlier in the day Robert Kennedy had spent forty-five minutes at

the White House briefing his brother on the events of the weekend and the