Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

246 Freedom Riders

political and legal dilemmas posed by the Freedom Riders’ unexpected per-

sistence. Despite public pronouncements to the contrary, many of the mar-

shals had not performed well under pressure, the attorney general confessed,

and the events of the weekend had cast serious doubt on their reliability as

peacekeepers in the Deep South. Reliance on the state police and the Na-

tional Guard also involved a certain amount of risk, but it did not present the

serious problems of political liability provoked by the deployment of mar-

shals. While the marshals had been a necessary means of forcing Patterson to

mobilize the National Guard, their continued presence in Alabama was po-

litically problematic and even dangerous. The decision to deploy the mar-

shals had already drawn considerable fire from conservative politicians in

both parties, including non-Southerners such as Senator Barry Goldwater of

Arizona, and such criticism was likely to increase dramatically if the marshals

remained in Alabama much longer. The task at hand, the Kennedy brothers

concluded, was to arrange for a graceful retreat without weakening the in-

tegrity of federal authority or appearing to abandon the Freedom Riders.

The latter challenge was especially acute in view of the Freedom Riders’

continuing vulnerability to arrest and intimidation by state and local offi-

cials. Robert Kennedy, in particular, agonized over the prospect of standing

by while Alabama authorities carted the Freedom Riders off to jail. But by

late Monday afternoon no one in the White House or the Justice Depart-

ment had come up with a plan that would get both the marshals and the

Freedom Riders safely out of Alabama.

One of the most frustrating aspects of the administration’s unenviable

position had been the ambiguous role of the FBI in Alabama. In the week

since the initial riots in Anniston and Birmingham, FBI officials at all levels

had kept a respectful distance from the developing crisis. At this point no one

outside of the bureau was aware of Gary Thomas Rowe’s involvement in the

Birmingham riot, but the inevitable grousing in the attorney general’s office

about the FBI’s apparent failure to keep tabs on the Alabama Klan had al-

ready pushed J. Edgar Hoover into preemptive action. On Monday morn-

ing, May 15, Hoover informed Burke Marshall and Robert Kennedy that the

Birmingham office of the FBI had begun an investigation of the Anniston

bus-burning incident. Given the code name FREEBUS, the investigation

initially drew plaudits from both Marshall and Kennedy, who made a point

of thanking the notoriously thin-skinned Hoover for giving the matter prompt

attention. As the week progressed, however, it became clear to Seigenthaler,

Doar, and other Justice Department officials in Alabama that Hoover and his

agents were more interested in enhancing the bureau’s public image than in

protecting the Freedom Riders’ constitutional rights. Although there were

several special agents at the Montgomery riot scene on Saturday morning,

none made any attempt to intervene on behalf of the men and women under

attack. Instead, they seemed content to conduct motion picture surveillance

through the windows of several parked vans, an activity that later took on a

If You Miss Me from the Back of the Bus 247

farcical touch when it was discovered that all of their film was defective. Less

comically, the reluctance of the bureau’s Alabama agents to provide the mar-

shals with logistical support during the Sunday evening siege led a frustrated

William Orrick to complain to Robert Kennedy, who promptly relayed the

criticism to the White House. Sometime after midnight the president for-

warded the complaint to Director Hoover’s office, which immediately or-

dered the Alabama agent in charge to give Orrick whatever he wanted in the

way of support.

Later that morning, around 9:30, Robert Kennedy received an unchar-

acteristically solicitous call from Hoover himself. After pledging his coop-

eration, the director delivered the welcome news that the bureau had just

arrested four of the men responsible for the Anniston bus burning. All four,

including an unemployed teenager, were active members of the Klan. To

Kennedy, who had just returned to his office after a few hours of fitful sleep,

the arrests could not have been more timely. After thanking Hoover for the

bureau’s good work, he immediately issued a press release declaring that the

case against the four Klansmen would “be pursued with utmost vigor.”

Hoover was also pleased, having relieved some of the pressure on the

bureau. After hanging up, though, he complained to his staff that he wasn’t

sure that the attorney general understood the nature of the real danger in

Alabama. Outside agitators like King and the Freedom Riders, he was con-

vinced, were actually more dangerous than the Klan. As radical provocateurs

and Communist fellow-travelers, they represented a serious threat to civic

order and national security, and they were certainly not the kind of people

that deserved a special FBI escort, which he feared was part of the Justice

Department’s plan. Throughout the Freedom Rider crisis, Hoover reiter-

ated his long-standing insistence that the FBI was an investigative agency

and “not a protection agency,” but he wasn’t sure that he could trust the new

attorney general to respect its time-honored prerogatives. Realizing that he

might need hard evidence of Communist infiltration to head off such an un-

pleasant assignment, Hoover ordered an immediate investigation of King,

the one agitator he was fairly certain had close ties to subversive groups.

Later in the day, he received a preliminary report that noted several suspi-

cious connections, including King’s ties to the Highlander Folk School, which

was described as a “Communist Party training school.” Intrigued, Hoover

urged his staff to dig deeper into what he suspected was a sinkhole of subver-

sion and unsavory activity.

40

Back in Montgomery, King and the Freedom Riders had no way of know-

ing that Hoover and the FBI had launched an investigation that would be-

come an important part of a decade-long effort to discredit the civil rights

movement. But they had few illusions about the support that federal officials

were prepared to offer. King’s early-morning conversation with Robert

Kennedy about the danger of placing the marshals under state control had

ended badly, and nothing had happened since to indicate that the Justice

248 Freedom Riders

Department was ready to provide the kind of protection that would guaran-

tee the Freedom Riders’ safe passage to New Orleans. Even more important,

despite the rhetoric coming out of Washington about the sanctity of inter-

state commerce, the administration’s commitment to upholding the Free-

dom Riders’ constitutional rights seemed hollow in the light of Kennedy’s

plea to postpone the Ride. All of this weighed heavily on the hearts and minds

of the Riders in the hours following the evacuation of First Baptist. In the

early-morning confusion the Riders had scattered throughout Montgomery’s

black community, but by late Monday afternoon virtually the entire contin-

gent had regrouped at the home of Dr. Richard Harris, a prominent black

pharmacist and former neighbor of King’s. Joined by an array of movement

leaders—including King, Abernathy, Walker, Farmer, CORE attorney Len

Holt, Nash, and Ed King of SNCC—the Riders turned Harris’s luxurious

three-story brick home into a combination refuge and command center.

During the next two days, Harris’s sprawling den became the backdrop

for a marathon discussion of the future of the Freedom Ride. The conversa-

tion ultimately touched on all aspects of the Freedom Riders’ situation, from

narrow logistical details to broad philosophical considerations of nonviolent

struggle. The first order of business was finding a solution to the Riders’

legal problems. In an ironic twist, Patterson’s declaration of martial law had

suspended normal civil processes, temporarily negating Judge Jones’s injunc-

tion within the city limits of Montgomery, but the Riders were still subject to

arrest everywhere else in Alabama. In an effort to remedy this situation, move-

ment attorneys Fred Gray and Arthur Shores went before Judge Frank

Johnson on Monday afternoon seeking to vacate the injunction. Held at the

federal court house adjacent to the Greyhound terminal, the hearing required

John Lewis and the other Riders accompanying Gray and Shores to pass by

the scene of the Saturday morning riot. This time the streets were patrolled

by National Guardsmen, and the courtroom was ringed with federal mar-

shals. The atmosphere was tense nonetheless.

As the Riders’ designated plaintiff and primary witness, Lewis—still

bruised and heavily bandaged—was called upon to explain the motivations

behind both the original CORE Ride and the Nashville Ride. It was a simple

question of exercising legal and constitutional rights, the young Freedom

Rider told Johnson, in a quavering voice that betrayed both his nervousness

and his passion for equal justice. After a brief deliberation, Johnson issued a

ruling affirming that very point: Judge Jones’s injunction represented an un-

constitutional infringement of federal law. The Freedom Riders were no

longer fugitives, Johnson declared, though he could not help questioning the

wisdom of continuing the Ride at the risk of civic disorder.

With the immediate threat of arrest eliminated by Judge Johnson’s rul-

ing, the Riders and their advisors began to consider an expanded range of

options. While virtually all of the Riders spoke out in favor of resuming the

Freedom Ride, the large contingent from Tennessee State faced a special

If You Miss Me from the Back of the Bus 249

dilemma. Threatened with expulsion by Tennessee governor Buford Ellington,

who had ordered state education commissioner Joe Morgan to investigate the

recent protest activities of public university students, the twelve Tennessee

State Riders were under heavy pressure to return to Nashville to attend the

final week of spring semester classes. In the end, all but one—Lucretia

Collins, a senior who had already fulfilled the requirements for graduation—

reluctantly decided to head back to school, forfeiting their chance to be among

the first Riders to travel to Mississippi. With their departure, the number of

available Nashville Riders fell to less than a dozen, including Lawson and

four other NCLC ministers—C. T. Vivian, John Lee Copeland, Alex Ander-

son, and Grady Donald—who had offered to reinforce the students. Nash,

however, had already enlisted additional reinforcements from other move-

ment centers, some from Atlanta and New Orleans and others from as far

away as Washington and New York. Although several were still en route as

late as Tuesday evening, she expected to have at least twenty volunteers in

Montgomery by the time the Freedom Ride departed for Mississippi on

Wednesday morning.

Before anyone could actually board the buses, however, there were a

number of important matters to attend to, including working out clear lines

of organizational authority and responsibility. Complicated by generational

and ideological divisions, the ongoing discussion among students and older

movement leaders took several unexpected turns on Monday evening. Ig-

noring the democratic sensibilities of the students, Farmer took immediate

charge of the meeting, to the obvious consternation of Nash, Lewis, and

others. Farmer, Lewis recalled years later, began and ended with self-serving

pronouncements on CORE’s centrality. “He talked loud and big,” Lewis

remembered, “but his words sounded hollow to me. His retreat after the

attacks in Anniston and Birmingham had something to do with it, I’m sure,

but he just struck me as very insincere. It was clear to everyone that he wanted

to take the ride back now, when we all knew that without our having picked

it up, there would have been no more Freedom Ride. It didn’t matter to me

at all who got the credit; that wasn’t the point. But from where Farmer stood,

that seemed to be all that mattered. He saw this ride in terms of himself. He

kept calling it ‘CORE’s ride,’ which amazed everyone.” Some students openly

challenged the CORE leader’s proprietary claims, while others quietly wrote

him off as an organization man hopelessly out of touch with the spirit of the

modern movement. But most of the attention ultimately focused on King

rather than Farmer.

King’s personal participation in direct action had been a major topic of

discussion since the time of the Greensboro sit-ins, and his recent support of

the CORE and Nashville Freedom Rides had triggered speculation that at

some point he might become a Freedom Rider himself. Earlier in the week

Diane Nash had broached the subject during a phone conversation with King,

suggesting that his presence on one of the freedom buses was essential to the

250 Freedom Riders

movement, but prior to the Monday night meeting there was no organized

or collective effort to persuade him to join the Freedom Ride. Though dis-

couraged by King’s noncommittal response to her initial entreaties, Nash

decided to try again in the more public setting in Montgomery. After con-

sulting with SNCC advisor Ella Baker, who encouraged her to press King on

the matter, the young Nashville activist steeled her courage and asked King

directly if he were willing to join the coming ride to Mississippi. By setting a

personal example of commitment, she explained, he could advance the cause

of nonviolent struggle to a new level. Momentarily caught off guard, King

responded that Nash was probably right, but he needed time to think about

it. As several other students seconded Nash’s suggestion, Walker, Abernathy,

and Bernard Lee—a young SCLC staff member from Montgomery who had

been active in the student movement at Alabama State—moved to quash the

idea with a series of objections: King was too valuable a leader and too criti-

cal to the overall movement to be put at risk. He had already put his body on

the line at First Baptist and elsewhere, they argued, and did not need to

prove his courage by engaging in a reckless show of solidarity. When it be-

came clear that King was uncomfortable with this line of reasoning, Walker

offered a more specific objection, reformulating a legal argument that SCLC

attorneys had advanced in anticipation of such a debate. Since King was still

on probation for a 1960 Georgia traffic citation, Walker declared, he could

not risk an additional arrest, which might put him in prison for as much as six

months.

For a moment this seemed to provide King with a graceful means of

deflecting Nash’s suggestion, but several of the students quickly pointed out

that they too were on probation. With King wavering, Nash and others pressed

for an answer. King’s response, tempered by his obvious discomfort with

being put on the spot, was a qualified no. As much as he would like to join

them on the Ride, he informed the students, he could not allow himself to be

forced into a commitment that threatened the broader interests of the move-

ment. Resorting to a biblical allusion to Christ’s martyrdom, he brought the

discussion to an abrupt end with the insistence that only he could decide the

“time and place” of his “Golgotha.” He then left the room for a private con-

versation with Walker, who returned a few minutes later with the word that

further discussion of the matter was off-limits. For the moment, at least, the

face-to-face tension was broken, though many in the room resented Walker’s

admonition as a violation of movement democracy. While virtually all of the

students recognized King’s dilemma, the abrupt suspension of debate was a

rude jolt, especially to those inclined to reject the stated rationale for the

SCLC leader’s decision. As the meeting broke up, one disappointed student

muttered, “De Lawd,” a mocking reference to King’s assumption of Christ-

like status, and others were visibly upset by what they had witnessed.

Later in the evening, Lee and Abernathy, along with Lewis, did their

best to smooth things over with the most disillusioned students, but for some

If You Miss Me from the Back of the Bus 251

King’s mystique was permanently broken. Paul Brooks was reportedly so

upset that he called Robert Williams, the radical NAACP leader in Monroe,

North Carolina, to vent, prompting an acerbic telegram from Williams to

King. “The cause of human decency and black liberation demands that you

physically ride the buses with our gallant Freedom Riders,” Williams in-

sisted. “No sincere leader asks his followers to make sacrifices that he himself

will not endure. You are a phony. Gandhi was always in the forefront, suffer-

ing with his people. If you are a leader of this nonviolent movement, lead the

way by example.”

41

ON TUESDAY MORNING the movement conclave at Dr. Harris’s house contin-

ued to wrestle with the issues of organizational harmony and personal com-

mitment, but the scene inside the house was calm compared to what was

going on elsewhere. On Monday evening sporadic violence, multiple bomb

threats, and “roving gangs of white youths” had forced General Graham to

dispatch 150 National Guardsmen to reinforce the fifty Guardsmen patrol-

ling the area around the Greyhound terminal, and the fear of additional dis-

ruption was still palpable the next morning. Most of the action, however, was

in the corridors of power in Montgomery, Jackson, and Washington. With

martial law still in effect and with the resumption of the Freedom Ride sched-

uled for Wednesday morning, Tuesday was a time for public posturing and

behind-the-scenes negotiation. All through the day there were signs of rising

apprehension and mobilization, especially in Mississippi.

In a morning telegram to Robert Kennedy, Governor Ross Barnett

warned: “You will do a great disservice to the agitators and the people of the

United States if you do not advise the agitators to stay out of Mississippi.” At

the same time, Barnett—an outspoken sixty-three-year-old white suprema-

cist with close ties to the White Citizens’ Councils—assured the attorney

general that the Magnolia State would not tolerate the kind of mob violence

that had erupted in Alabama. “The people of Mississippi are capable of han-

dling all violations of law and keeping peace in Mississippi,” he insisted. “We

. . . do not want any police aid from Washington, either marshals or federal

troops.” To prove his point, Barnett placed the Mississippi National Guard

on alert and authorized state troopers to search for Freedom Riders at check-

points along the Alabama-Mississippi border. Later in the day, Barnett’s plan

of action received the endorsement of John Wright, the head of the Jackson

White Citizens’ Councils, who declared: “Mississippi is ready. . . . Our Gov-

ernor, the Mayor of Jackson and other state and city officials have already

stated plainly that these outside agitators will not be permitted to stir up

trouble in Mississippi.” Pointing out that “the vast majority of our public

officials are Citizens’ Council members,” Wright urged his fellow Mississip-

pians to let “our Highway Patrolmen, policemen and other peace officers

handle any situation which may arise. . . .You and I can help by letting our

252 Freedom Riders

public officials and police officers know that we’re behind them all the way—

and by not adding to their problems in time of crisis.”

42

Such calls for restraint buoyed the spirits of Justice Department officials

and others who had worried that Mississippi segregationists were even more

prone to vigilantism and violence than their Alabama cousins. Earlier in the

week former Mississippi governor James Coleman had warned Burke Marshall

that he feared that the Freedom Riders would “all be killed” if they tried to

cross the state without a military escort, and other sources had confirmed the

seriousness of the threat. Thus Barnett’s call for law and order was a wel-

come sign. The implication that Mississippi was determined to avoid

Alabama’s mistakes did not sit well, however, with John Patterson, who lashed

out at his critics in a Tuesday afternoon press conference. Meddling federal

authorities, he declared, not local or state officials, were to blame for the

mayhem and rioting in the streets of Montgomery. As he had predicted, the

unwarranted intrusion of federal marshals had fanned the flames of interra-

cial violence, making it impossible for local and state law enforcement offic-

ers to maintain civic order. “If the marshals want to contribute to law and

order they should go home,” he insisted. From the outset of the Freedom

Rider crisis, he had maintained that respecting state sovereignty was the best

way—indeed, the only way—to insure law and order in Alabama, but the

president and the attorney general had refused to listen to him. While he still

considered the president “a friend of mine,” he urged the Kennedy adminis-

tration to use its “prestige and power” to persuade the so-called Freedom

Riders to leave Alabama as soon as possible. “If they want to go to the state

line we will see that they get there,” he assured the reporters, adding: “I’m

opposed to agitation and mob violence no matter who does it. But it’s just as

guilty to provoke an incident as to take part in one.”

43

Patterson’s bombastic performance made good copy, but it could not

compete with the drama of another press conference held earlier in the day.

Determined to sustain the momentum of the Freedom Ride and eager to

demonstrate the solidarity of the coalition that had formed over the past

week, King and several other movement leaders abandoned the security of

Dr. Harris’s house to brief the press on their plans. Surrounded by federal

marshals and a crush of local, national, and international reporters, Farmer,

Abernathy, and Lewis explained why they and their organizations—CORE,

SCLC, and SNCC—were committed to resuming the Freedom Ride. King

then read a joint declaration vowing that the Freedom Riders would soon

board buses for Mississippi, with or without guarantees of police protection.

Prior to their departure the Freedom Riders would participate in a nonvio-

lent workshop led by Nashville Movement leader Jim Lawson, King an-

nounced. And to make sure that the reporters understood the implications of

extending the nonviolent movement into Mississippi, he put down the pre-

pared text and spoke from the heart. “Freedom Riders must develop the quiet

courage of dying for a cause,” he declared, his voice cracking with emotion.

If You Miss Me from the Back of the Bus 253

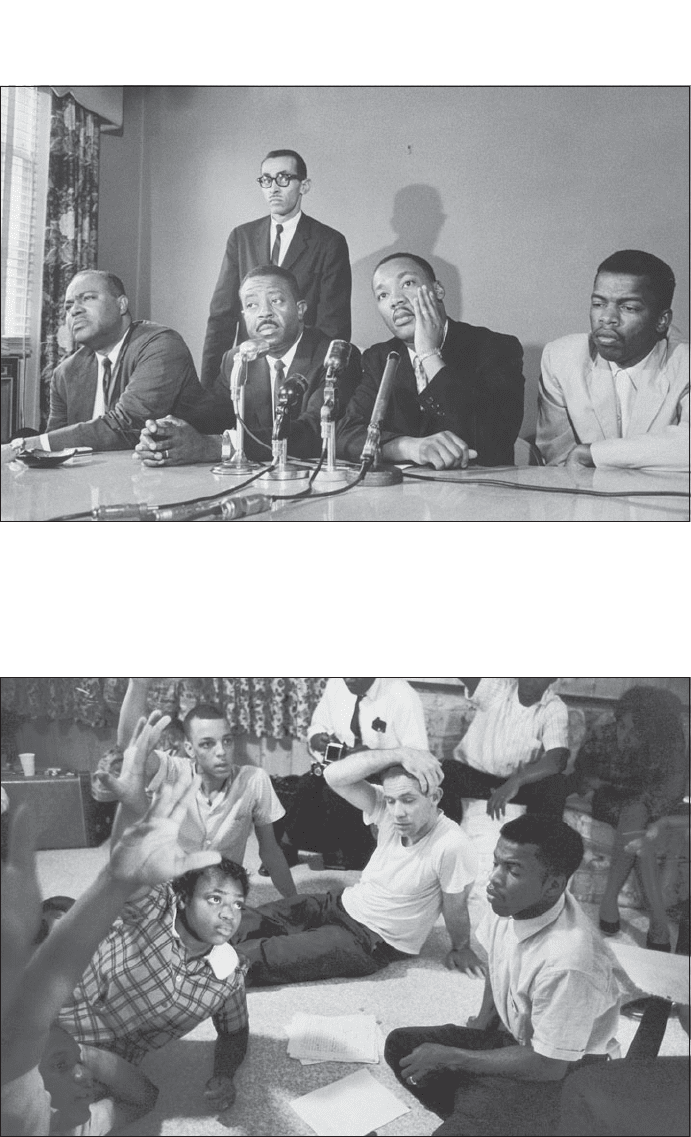

Freedom Riders and civil rights leaders hold a press conference in Montgomery,

Tuesday, May 23, 1961. From left to right: Jim Farmer, Wyatt Tee Walker (stand-

ing in background), Ralph Abernathy, Martin Luther King Jr., and John Lewis.

(Photograph by Bruce Davidson, Magnum)

Freedom Riders Julia Aaron, David Dennis, Paul Dietrich, and John Lewis par-

ticipate in a planning session at the Montgomery home of Dr. Richard Harris,

Tuesday, May 23, 1961. (Photograph by Bruce Davidson, Magnum)

254 Freedom Riders

“We would not like to see anyone die. . . . We all love life, and there are no

martyrs here—but we are well aware that we may have some casualties. . . .

I’m sure these students are willing to face death if necessary.”

44

King’s dramatic statement cleared the air and clarified the Freedom Rid-

ers’ sense of purpose. But it also reinforced the public misconception that he

was the supreme leader and chief architect of the Freedom Rides. In truth,

he had never been a central figure in the Freedom Rider saga, and his refusal

to join the Mississippi Ride had further marginalized his position among the

student activists in Montgomery. To the outside world the celebrated founder

of SCLC inevitably represented the moral compass of the movement, but to

the students themselves his moral authority was uncertain at best. That

evening, when they gathered to finalize preparations for Wednesday morn-

ing, the question of King’s participation in the Mississippi Freedom Ride

came up again. This time the discussion included Jim Bevel, who had driven

down from Nashville earlier in the day with three new recruits: Rip Patton of

Tennessee State, and LeRoy Wright and Matthew Walker Jr. of Fisk. Lawson

was also on hand, having arrived a few hours later in a second carload of

NCLC reinforcements.

Before leaving Nashville, Lawson dismissed the importance of his role

as workshop coordinator, graciously insisting to reporters that King was “in

over-all charge” of the Montgomery gathering, and during the discussion of

King’s proper role in the Freedom Rides, he and Bevel, among others, de-

fended the SCLC leader’s decision to serve as a spokesperson and fund-raiser

rather than as an actual Freedom Rider. Though well-intentioned, the cam-

paign to enlist King as a Freedom Rider had become problematic in their

eyes. In practical terms, it threatened the fragile alliance between SCLC and

the student movement; perhaps even more important, pursuing the effort

after King’s reluctance became clear violated the philosophical principles of

nonviolent struggle, in which individual conscience was the only proper ar-

biter of bodily and spiritual commitment. Many others in the room, regard-

less of their position on King’s involvement, had reached the same conclusion

and were relieved when the center of attention shifted to Lawson’s nonvio-

lent workshop.

For several hours, Lawson led the Riders through a reprise of the ses-

sions that had been instrumental to the Nashville Movement. Nearly half of

the Riders were from Nashville and had seen Lawson work his magic before,

but others were encountering his quiet intensity for the first time. While

everyone in the room had practical experience with sit-ins and other forms of

direct action, Lawson’s presentation of nonviolence as an all-encompassing

way of life provided some with a new philosophical grounding for their activ-

ism. Indeed, several of the Freedom Riders would look back on the final

hours in Dr. Harris’s den as a life-changing experience, one that deepened

their theoretical understanding of nonviolent struggle and sacrifice, prepar-

ing them as nothing else had for the difficult challenges ahead.

If You Miss Me from the Back of the Bus 255

Among those present at the workshop were three Riders representing

New Orleans CORE and four SNCC activists representing Washington’s

Nonviolent Action Group. Jail terms had forced two members of the New

Orleans group—Julia Aaron and Jerome Smith—to miss the original May 4

CORE ride, and they were anxious for a second chance to become active

Freedom Riders. The journey to Alabama also represented a second chance

for John Moody, who, along with Paul Dietrich, had left Washington by car

on Saturday. Driving as far as Atlanta, they had flown in on the same plane as

King on Sunday morning. Also on hand were two other NAG stalwarts, Dion

Diamond, a Howard student from Petersburg, Virginia, who had taken final

exams early so that he could join the Freedom Ride in Montgomery, and

Hank Thomas, who had flown to Montgomery after several days of recu-

peration in New York. Some of the new volunteers did not arrive in Mont-

gomery until Tuesday evening and missed the early part of the workshop,

but by the time the gathering broke up around midnight, the number of

potential Freedom Riders had risen to almost thirty, enough for two free-

dom buses, one Greyhound and one Trailways. While no one knew exactly

how many Riders would actually board the buses in the morning, the stage

was set for the nonviolent movement’s first major project in Mississippi.

45

The nonviolent workshop and the camaraderie that surrounded it pro-

duced moments of exhilaration and renewal. But, as several of the Riders

later acknowledged, the final hours in Montgomery also brought feelings of

dread, including fearful thoughts of what might actually happen in Missis-

sippi. Making an interracial foray into Mississippi had always been a fright-

ening prospect, but earlier in the day the Riders learned that even Medgar

Evers, the Mississippi NAACP’s state field secretary, had confessed to re-

porters that he hoped the Freedom Riders would postpone their trip to Jack-

son. In his words, under the present circumstances it was simply “too

dangerous” to force a confrontation with Mississippi segregationists. During

the workshop, Lawson, Holt, and others urged the Riders to ignore Evers’s

warning. But they did not deny the seriousness of the situation. “Although

the law is on your side, you don’t have any rights that any Southern state is

bound to respect,” Holt reminded the Riders during a discussion of the legal

obstacles to nonviolent protest in Mississippi. “Please try to remember that,

so that you’ll be prepared for anything.” He insisted that “participants in the

Freedom Ride must go stripped for action. I know some of you may be tense

and upset from what you’ve experienced for the past few days, but don’t take

any sleeping pills or aspirins with you that could be labeled as narcotics. . . .

Don’t even carry any medicine containing alcohol. . . . Get rid of any long

hair pins, fingernail files or necklaces which could be called dangerous weap-

ons. These people will be trying to find anything they can to arrest you for.

. . . Whatever happens, be firm but polite. Remember you have no rights. . . .You

can’t fight back.”