Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

256 Freedom Riders

Holt’s sobering advice focused on the perils of protest in Mississippi, but

the Riders also had to face the possibility that they might not make it out of

Montgomery. Indeed, much of the discussion during and after the workshop

focused on the likelihood of more mob violence at the local bus stations.

Federal and state officials had promised to protect them from white vigilan-

tes, but few of the Riders were confident that these promises would be kept.

Considering the events of the past week and the continuing public banter

about state sovereignty, the intentions of law enforcement officials at all lev-

els were open to question. As the Sunday night siege had demonstrated, there

was even some doubt about the federal government’s ability to protect the

Riders. Could the limited number of federal marshals and National Guards-

men on the ground in Alabama and Mississippi muster enough force to hold

back a large and determined mob? None of the Riders could be sure, since,

aside from a few general and mildly comforting assurances, the details of the

government’s plans were unknown to them. Many of the Riders had decided

to go to Mississippi no matter what the risk, but, as several of them sat down

to write wills and final letters to loved ones before drifting off to bed, the

uncertainties of the situation tested their already frayed nerves.

46

Had the Freedom Riders been privy to the government’s planned secu-

rity measures, they might have slept a little easier. Although some of the

details were still being worked out on Tuesday evening—and even into the

morning hours—several days of close collaboration between federal and state

authorities in Mississippi and Alabama had produced a consensus that a mas-

sive show of force was needed to forestall any chance of violence. In a final

flurry of phone calls, Byron White and Governor Ross Barnett put the fin-

ishing touches on a military operation “worthy of a NATO war game,” as

one historian later put it. Unfortunately, the close collaboration also pro-

duced a tacit understanding that once the Freedom Riders arrived in Jackson

there would be no federal interference with local law enforcement. Earlier in

the week Barnett had promised “nonstop rides” for the Freedom Riders. Now

it appeared that Barnett was contemplating mass arrests and a declaration of

martial law. Unbeknownst to White and other federal officials, the governor

was even considering an alternate and more extreme plan that would put the

Freedom Riders in a state mental hospital.

While White stated emphatically that the Justice Department hoped that

the Freedom Riders would be allowed to travel on to New Orleans, he did

not insist upon it—in part because his superiors at the Justice Department

and the White House had decided that it was too risky to use federal mar-

shals or military personnel in Mississippi, but also because Robert Kennedy

had already struck a deal with the state’s senior senator, James O. Eastland.

After ex-governor James P. Coleman warned Marshall that Barnett was a

rank demagogue who “could not be trusted,” Kennedy turned to Eastland,

whom he considered to be a political and even personal friend. Unlike many

Northern senators, Eastland had been an enthusiastic supporter during

If You Miss Me from the Back of the Bus 257

Kennedy’s confirmation hearings, and despite the obvious ideological gulf

between them, the two men had developed a mutual trust during the early

months of the new administration. Over the course of three days and several

dozen phone conversations, this trust deepened as Eastland convinced the

young attorney general that he would see to it that Mississippi’s response to

the Freedom Rides served the best interests of the nation. Despite his unwa-

vering commitment to segregation, Eastland promised Kennedy that no harm

would come to the Freedom Riders in Mississippi; however, he could not

guarantee that they would escape arrest. Indeed, Eastland hinted that any

attempt to violate Mississippi’s segregation laws would result in mass arrests.

Though hardly pleased with the prospect of jailed Freedom Riders, Kennedy

assured Eastland that the federal government’s “primary interest was that

they weren’t beaten up.”

While he did not say so on the phone, Kennedy knew all too well that he

was in no position to press Eastland on this point. If the Jackson police chose

to put the Freedom Riders in jail, there wasn’t much that he or any other

federal official could do about it. In effect, the rioting in Alabama had con-

vinced the Kennedy brothers, along with White and Marshall, that almost

anything was preferable to mob violence—including unconstitutional arrests

of interstate travelers. Ironically, a tentative show of force in one state had

undercut federal authority in a second. As events would soon demonstrate,

the situation was made to order for Barnett, a militant segregationist eager to

cement his ties to the White Citizens’ Councils. Realizing that he had been

handed a scenario that would allow him to take credit for maintaining both

order and segregation, he was almost giddy by the time the arrangements

were complete. Inviting White to accompany the Freedom Riders to Jack-

son, Barnett promised that the Mississippi Highway Patrol would see to it

that he had “the nicest ride.” “You’ll be just as safe as you were in your baby

crib,” Barnett added with a chuckle.

47

In later years, some members of the administration—prompted by civil

rights leaders and historians who condemned the negotiations with Eastland

as a betrayal of democratic ideals—would acknowledge that the agreement

to defer to state authorities was a mistake. At the time, however, Robert

Kennedy and his colleagues regarded the deal as an unpleasant but necessary

resolution to a crisis that had already taken up too much of the administration’s

time and energy. In their eyes, the decision to accede to Eastland’s demands

was simply a postponement of the day of reckoning and not a surrender.

Sometime in the future the federal government would find a way to guaran-

tee the right to travel from state to state without accommodating outdated

segregationist laws and customs. But under the current conditions of Cold

War politics, administration leaders did not feel that they could afford a pro-

longed crisis that would almost certainly weaken the Democratic Party and

embarrass the nation in front of the world. In their view, the realities of both

domestic and international political life dictated a moderate course of action.

258 Freedom Riders

As the government official shouldering the ultimate responsibility for

the Freedom Riders’ arrests, John Kennedy could take comfort in the knowl-

edge that he was following a long tradition of presidential pragmatism. Like

many presidents before him, including Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lin-

coln, he could claim that he was simply doing the best he could with a diffi-

cult situation. Indeed, against the dual backdrop of the Civil War Centennial

and the civil rights movement, the comparison with Lincoln was inevitable.

In the wake of Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963, pointing out the

parallels between the two martyred presidents became a popular pastime,

with some observers noting the broad and substantive similarities between

the historical challenges of the Lincoln and Kennedy eras.

A century before the Freedom Rider crisis, Lincoln had faced a similarly

wrenching dilemma involving the competing interests of political realism

and moral urgency. As a moderate Republican candidate in 1860, he com-

mitted his party to the twin goals of saving the Union and excluding slavery

from the territories. But, as he freely admitted, the two goals were not yet

equal, or even compatible. If forced to choose between partial abolition and

the preservation of the Union, he would choose the latter. It would take two

years of armed conflict and abolitionist ferment to push Lincoln toward a

more humane and democratic resolution of this dilemma. Only in Septem-

ber 1862 did he and the nation reach what the historian James McPherson

has labeled the “crossroads of freedom.” By issuing the Emancipation Proc-

lamation in the aftermath of the Union victory at Antietam, Lincoln estab-

lished the immediate abolition of slavery in the seceded states and a perpetual

Union as complementary war aims. Even though nearly three years of brutal

warfare—not to mention a century of largely unfulfilled promises—lay ahead,

the road taken from Antietam led African Americans to eventual, if incom-

plete, freedom.

In late May 1961, John Kennedy faced the Lincolnesque challenge of

extending that road through the Deep South. By sending federal marshals to

Alabama and affirming the constitutionally protected rights of all Americans,

Kennedy had taken an important first step toward the implementation of

racial justice. But on the morning of the twenty-fourth, as the Freedom Rid-

ers prepared to hack out a path of progress through the magnolia jungle of

Mississippi, no one could be quite sure how far or fast the young president

was willing to travel.

48

7

Freedom’s Coming and

It Won’t Be Long

We took a trip on a Greyhound bus,

Freedom’s coming and it won’t be long.

To fight segregation where we must,

Freedom’s coming and it won’t be long.

Freedom, give us freedom,

Freedom’s coming and it won’t be long.

—1961 “calypso” freedom song

1

THE FEDERAL PRESENCE in Alabama and Mississippi was both everywhere and

nowhere on Wednesday morning, May 24. Having asserted the power and

authority of the national government, the Kennedy administration had with-

drawn, at least temporarily, to the sidelines. The short-term, if not the ulti-

mate, fate of the Freedom Ride had been placed in the hands of state officials

who, paradoxically, had promised to protect both the safety of the Riders and

the sanctity of segregation. When the Trailways group of Freedom Riders

left Dr. Harris’s house at 6:15

A.M., they were escorted by a half-dozen jeeps

driven by Alabama National Guardsmen. This unimpressive show of force

raised a few eyebrows among the Riders, who knew next to nothing about

the details of the plan to protect them. But as the convoy approached the

downtown Trailways terminal, the familiar outline of steel-helmeted soldiers

came into view. In and around the terminal, more than five hundred heavily

armed Guardsmen stood watch over several clusters of white bystanders. Al-

though the Freedom Riders did not know it, there were also several FBI

agents and plainclothes detectives nervously wandering through the crowd.

As the Freedom Riders filed out of their cars, the scene was tense but quiet

until the crowd spotted King, who, along with Abernathy, Shuttlesworth, and

Walker, had agreed to accompany the Riders to the terminal. Still uncomfort-

able with his refusal to join the Ride, King was determined to provide the

260 Freedom Riders

disappointed students with as much visible support as possible. During an

early-morning prayer meeting at Harris’s house, he and Abernathy had blessed

the Riders; and in a show of solidarity his brother, A. D., had flown in from

Atlanta to help desegregate the Montgomery terminal’s snack bar. With some

members of the crowd screaming words of indignation, King led the com-

bined SCLC–Freedom Rider entourage through the white waiting room and

up to the counter, where he and the others ordered coffee and rolls. As sev-

eral reporters and cameramen pressed forward to record the moment, “the

white waitresses removed their aprons and stepped back,” but, with the ap-

proval of the terminal’s manager, black waitresses from the “Negro lunch

counter stepped up and took the orders,” thus breaking a half-century-old

local color bar. Local and state officials, it seemed, had put out the word that

nothing—not even the sanctity of Jim Crow dining—was to get in the way

of the Freedom Riders’ timely departure from Montgomery. Pleased, but

wary of this unexpected politeness, some of the Riders began to wonder

what other surprises were in the offing. They did not have to wait for very

long to find out.

Upon arriving at the Trailways loading bay, the Freedom Riders discov-

ered that there were no regular passengers waiting for the morning bus to

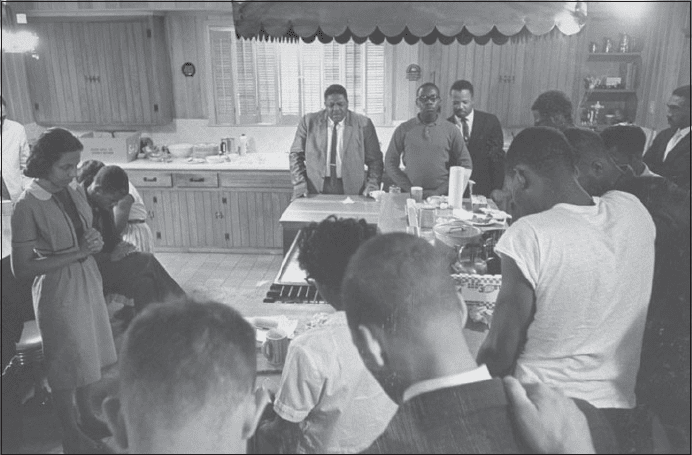

Prior to their departure for Mississippi, Freedom Riders hold a prayer breakfast

in Dr. Richard Harris’s kitchen in Montgomery, Wednesday morning, May 24,

1961. The man in the dark suit standing behind the table is A. D. King, brother

of Martin Luther King Jr. The man at the left corner of the table is the Reverend

Joe Boone of SCLC. The woman standing on the left is Diane Nash. The man in

the right foreground wearing a T-shirt is Hank Thomas. (Getty Photos)

Freedom’s Coming and It Won’t Be Long 261

Jackson. Alabama Guardsmen, on orders from General Graham, were only

allowing Freedom Riders and credentialed reporters to enter the bus. More

than a dozen reporters were already on board, and several others soon joined

them, as the Riders sized up the situation. Not all of the Riders were com-

fortable with the prospect of traveling to Jackson under such artificial condi-

tions, and others were simply scared to death, but eventually all twelve of the

Trailways Riders agreed to board the bus. Each, according to David Dennis,

a twenty-year-old Louisiana CORE activist and student at Dillard College,

“was prepared to die.” In addition to Dennis, the group included two South-

ern University students from New Orleans, Julia Aaron and Jean Thomp-

son; Harold Andrews, a student at Atlanta’s Morehouse College; Paul Dietrich

of NAG; and seven members of the Nashville Movement—Jim Lawson, Jim

Bevel, C. T. Vivian, Bernard Lafayette, Joseph Carter, Alex Anderson, and

Matthew Walker Jr. Three of the Nashville Riders—Lawson, Vivian, and

Anderson—were practicing ministers, and three others—Bevel, Lafayette,

and Carter—were divinity students. Dietrich was the only white. Walker and

Thompson were the youngest at age nineteen, and Vivian was the oldest at

thirty-six. Lawson, the third oldest at thirty-two, was the consensus choice as

the group’s designated leader and spokesperson.

2

Soon after the twelve Freedom Riders took their seats, General Gra-

ham, the movement anti-hero of the Sunday night siege, stepped onto the bus

to say a few words. Flanked by several Guardsmen, he warned the Riders—and

the newsmen scattered throughout the bus—that they were about to embark

on “a hazardous journey.” Seconds later, however, speaking in a reassuring

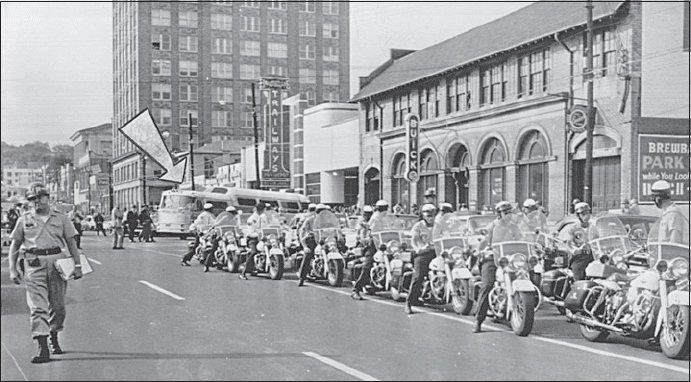

Accompanied by a military and police escort, the first group of Mississippi-bound

Freedom Riders leaves the Montgomery Trailways bus station, Wednesday morn-

ing, May 24, 1961. (Courtesy of Nashville Tennessean and AP Wide World)

262 Freedom Riders

voice, he insisted that “we have taken every precaution to protect you,” add-

ing: “I sincerely wish you all a safe journey.” This was not what the Riders had

come to expect from Alabama-bred officials, and several of the Riders thanked

him for humanizing their last moments in Montgomery. After Graham de-

parted, six Guardsmen remained on board, as an array of jeeps, patrol cars,

and police motorcycles prepared to escort the bus northward to the city lim-

its, where a massive convoy of vehicles was waiting. Once the bus reached

the city line, the magnitude of the effort to get the Freedom Riders out of

Alabama without any additional violence became apparent. In addition to

several dozen highway patrol cars, there were two helicopters and three U.S.

Border Patrol planes flying overhead, plus a huge contingent of press cars

jammed with reporters and photographers. As the Riders would soon dis-

cover, nearly a thousand Guardsmen were stationed along the 140-mile route

to the Mississippi border. Less obtrusively, there were also several FBI sur-

veillance units placed at various points along Highways 14 and 80. While

Graham, Mann, and other state officials were in the foreground running the

show, federal officials were in the background monitoring as much of the

operation as they could.

Leaving Montgomery a few minutes before eight, the convoy headed

west toward Selma, the first scheduled stop on the 258-mile trip to Jackson.

During the hour-long, fifty-mile journey to Selma, the Riders chatted ami-

ably with reporters, but when the bus arrived in the town that four years later

would become the site of the movement’s most celebrated voting rights march,

the National Guard colonel in charge of the bus announced that there would

be no rest stops on the journey to Jackson. Motioning to the crowds lining

the streets of Selma, the colonel did not have to explain why. But Lawson

and several of the other Riders made it clear that they did not appreciate the

heavy-handed style of protection being imposed on a Freedom Ride that was

supposed to test the constitutional right to travel freely from place to place.

“This isn’t a Freedom Ride, it’s a military operation,” Bevel yelled out, a

sentiment echoed by Lafayette, who confessed: “I feel like I’m going to war.”

At the same time, they couldn’t help wondering what kind of specific threats

had precipitated such extreme caution.

As the bus passed through Uniontown, thirty miles west of Selma, the

sight of fist-shaking whites on the side of the road was unnerving, but the

first sign of serious trouble came near Demopolis, where three cars of scream-

ing teenagers started weaving through the convoy in an attempt to chase

down the bus. After a brief stop, during which a nauseated Alex Anderson

momentarily left the bus to vomit on the side of the road, the teenagers were

detained long enough to allow the convoy to continue unimpeded to the

state line. The bus did not stop again until it reached the tiny border town of

Scratch Hill, Alabama. A few minutes later, the bus passed through the slightly

larger town of Cuba, prompting several of the Riders to serenade their com-

panions with what one reporter called “impromptu calypso rhythms.” One

Freedom’s Coming and It Won’t Be Long 263

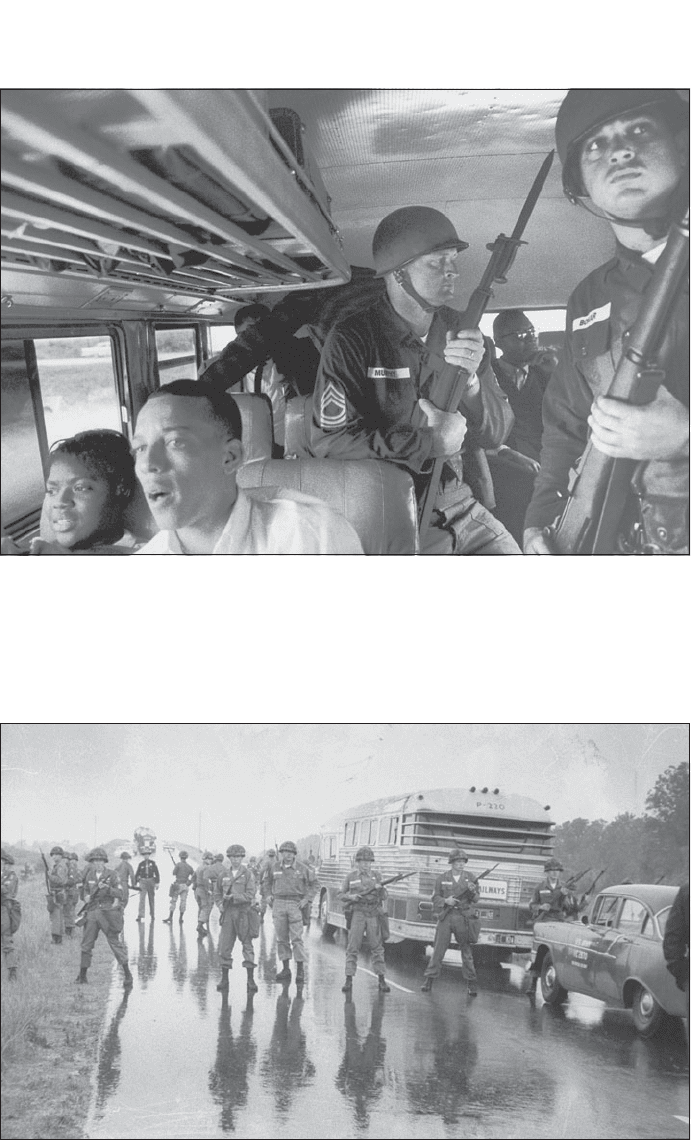

Freedom Riders Julia Aaron and David Dennis, with National Guardsmen, on the

first freedom bus to Mississippi, Wednesday morning, May 24, 1961. The man

sitting on the back seat is Jim Lawson. (Photograph by Bruce Davidson, Magnum)

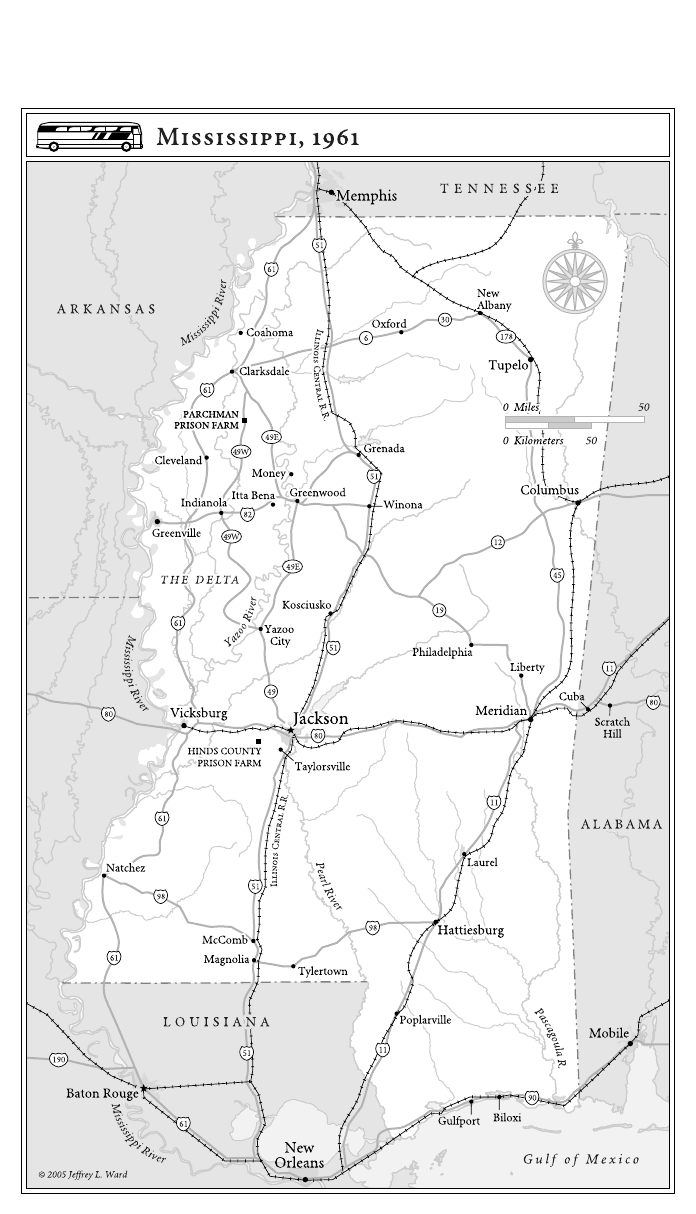

Alabama National Guardsmen protect the Freedom Riders’ Trailways bus near

the Mississippi border, Wednesday morning, May 24, 1961. (Photograph by Paul

Schutzer, Getty Photos)

264 Freedom Riders

Freedom’s Coming and It Won’t Be Long 265

of the songs, improvised by the Riders earlier in the journey, was an adaptation

of Harry Belafonte’s popular calypso ballad “The Banana Boat Song,” some-

times known as “Day-O.” “We took a trip on the Greyhound bus, freedom’s

coming and it won’t be long. To fight segregation where we must, freedom’s

coming and it won’t be long. Freedom, give us freedom, freedom’s coming

and it won’t be long,” the Freedom Rider chorus sang over and over again, as

waves of laughter rippled through the bus. Moments later, however, both

the music and the laughter gave way to the sobering reality of the martial

spectacle at the state line.

3

Matching their Alabama cousins, Mississippi authorities had assembled

a small army of National Guardsmen and highway patrolmen, enough to

escort half a dozen freedom buses into the state. If this was not bracing enough,

word soon came that Mississippi authorities had uncovered a plot to dyna-

mite the bus as soon as it crossed the state line. This and other unconfirmed

threats caused an hour’s delay, during which Mississippi Guardsmen searched

the nearby woods and General Graham and his Mississippi counterpart,

Adjutant General Pat Wilson, assessed the situation. While Wilson and

Graham worked out the details of the transfer, an impatient Jim Lawson

decided to hold an impromptu press briefing. To the amazement of the re-

porters encountering Lawson for the first time, the young minister com-

plained that the Freedom Riders had not asked to go to Mississippi in the

equivalent of an armored vehicle. As disciples of nonviolence, they “would

rather risk violence and be able to travel like ordinary passengers” than cower

in the shadow of protectors who neither understood nor respected their phi-

losophy of countering “violence and hate” by “absorbing it without return-

ing it in kind.” With the reporters still puzzling over what seemed to be a

foolhardy embrace of martyrdom, the bus resumed its journey around 11:30

A.M., nearly four hours after leaving Montgomery.

As soon as the bus crossed over the state line, Graham turned over con-

trol of the convoy to Mississippi’s commissioner of public safety, T. B.

Birdsong, and General Wilson, who promptly replaced the Alabama Guards-

men on board with six Mississippi Guardsmen under the command of Lt.

Colonel and future congressman G. V. “Sonny” Montgomery. After Wilson

informed the Freedom Riders and reporters on the bus there would be no

rest stops on the one-hundred-mile trip to Jackson, C. T. Vivian complained

to Montgomery that this decision was “degrading and inhumane,” consider-

ing that there was no restroom on the bus. Montgomery’s only response was

to order Vivian to sit down and be quiet. Stunned by this curt dismissal,

Vivian was unable to restrain himself. “Have you no soul?” he plaintively

asked Montgomery. “What do you say to your wife and children when you

go home at night? Do you ever get on your knees and pray for your inhu-

manity to your fellow man? May God have mercy on you.” Staring ahead,

Montgomery did not answer. While Vivian and others seethed, Birdsong

directed the motorcade toward Meridian, where the bus stopped briefly for