Burt A. The Evolution of the British Empire and Commonwealth From the American Revolution

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

More

Democracy

and

the

Quest

for

Social

Justice

505

in

1 898

he

carried

it

by

a

tour

de

force;

he

kept

the

House

in committee

without

a

break

for

nearly

ninety

hours,

occupying

the chair the whole

time

and

reprimanding

exhausted

members

who would

join

in the

debate

while

still

lying

down.

Among

other

features

of

welfare

legislation

enacted

by

this

ministry

were

government

loans

to

small

farmers

struggling

to establish them-

selves and

to

humble

town

dwellers for the

purchase

of

homes,

the

assumption

by

the

state

of

the

whole

responsibility

for

the

treatment

of

mental

diseases,

and

the

provision

of

state

maternity

hospitals

for

working

women.

Of

state

socialism

in

the strict

sense,

there

was little

extension,

and

that

little

was

mainly

to curb real or threatened

monop-

oly, notably

in

fire

insurance

and

coal

mining.

Quite

illuminating

is

the

way

the

government

handled the

country's

leading

private

financial

institution,

the

Bank of New

Zealand.

In

1894,

after

years

of

running

in

the

red

and

concealing

this fact

by

resorting

to

dishonest

practices,

it

begged

the

government

for

aid to

avert

an

immediate

crash.

The

government

rushed to the

rescue

in

return for

a

controlling

interest,

which

it

might

have

used

to

dictate

interest

rates,

exchange

charges,

and

lending policy.

But

there

was

no

attempt

at

any

such

interference.

The bank

was

allowed to

continue,

under more careful

management,

as an

ordinary

commercial

bank,

which is a

clear

indication that

state socialist

ideals had not

captured

the

community. Fortunately

the

government

lost not a

penny by

this

venture and

ultimately

made a

good

profit

out

of

it,

for

the

refloated

bank

was

borne

along by

the tide of

prosperity

that

began

to

flow

joyously

in

1896.

The socialistic trend

in

New

Zealand,

which was more

apparent

than

real,

slackened

as the

depression

lifted,

and it was

reversed in the

following

decade.

What caused this

reaction was

something

more than

the return of

prosperity,

which is

a

proverbial

cure for

radicalism.

The

very

success

of the Liberal-Labor

party

was its own

undoing.

As

more

and

more

people

were settled

on

the

land,

they

constituted a

growing

class of

conservatives

whose influence

with the

government

gradually

turned

the balance

against

organized

labor in the

towns,

and

trade

unionism

lost some

of

the

legislative

and administrative

favor that

it

had

gained.

Labor

naturally

broke

away

to form an

independent

and

more

radical

party,

which made

little

political impression

because

it

represented

a

dwindling

minority

of die

population.

On the

other

hand,

the

rising

demand

of

the small farmers to have

their

long

leases

transformed

into freehold

played

into the

hands of the

opposition

506

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

which,

reconstituted

as

the Reform

Party,

won the

election

of

1912

and

straightway

satisfied this demand.

But

the fall of

the

Liberals

was

not the

fall of

liberalism

or the

end

of social

democracy.

The

Conserva-

tives

had

to

shed much

of

their

conservatism

and be converted

into

Reformers

in

order to

get

back

into

power;

and

the rural

democracy

of

New

Zealand

was

no

less inclined than the

urban

democracy

of

Australia

to

operate

the

machinery

of

government

in its own

economic

and

social

interest.

CHAPTER

XXVIII

The

Great

Imperial

Scramble

ONE

OF the

most

extraordinary phenomena

of modern

times occurred

in the

last

two

decades of

the

nineteenth

century,

when western

powers

partitioned

the

huge

continent

of

Africa,

grabbed

pieces

of

Asia,

and

gobbled

up

the

countless

islands of the

Pacific.

Why

this mad

scram-

ble?

Not until

the turn

of the

century

did

a

serious

answer

begin

to

take

shape,

and

it

was then

the work of

bourgeois

liberals

in

America

and

England.

Their

work was

later

appropriated

and

developed

by

continental

socialists,

particularly

the

neo-Marxians,

who

propounded

the full-blown

theory

that

imperialism

was

simply

the

operation

of

predatory capitalism

which,

being

cramped

by

limited

opportunities

at

home,

was

seeking

new

worlds to

exploit;

that

the

government

of

each

imperialist

country

was a tool of

its

capitalists

who

were

using

it to

win

for

themselves

wider

markets,

more

raw

materials,

cheaper

labor,

and

fresh fields for

investment;

and that the

capitalist

system

was

rushing

to

its

own

destruction

by driving

the

international

competition

for these

prizes

toward

an

explosion

of suicidal wars.

This economic

interpreta-

tion without

its

catastrophic

conclusion,

which

was

added

by

the

apocalyptic

vision

of the communist

prophets, gained

wide

acceptance

among

liberals

in

western civilization.

It was so neat and

clear,

and

it

seemed

so

self-evident.

This

may explain

the curious fact that

there

was

almost

no

attempt

to

test its

validity by

a

critical

analysis

of

concrete

examples

of

imperialist

action.

A mere

glance

at the

previous period

is sufficient to

expose

the

inadequacy

of

the

theory.

In

the

heyday

of

anti-imperialism,

Britain

was

exporting great

quantities

of

goods

and

capital

to

all

parts

of

the

globe,

civilized

and

uncivilized,

and from

them she

was

importing

food

and

raw

materials.

Her

capitalism

had burst the bounds of

empire.

Two

thirds

of

her

trade,

by

which

she

lived,

was with countries

that

508

CHAPTER

TWENTY-EIGHT:

did

not

fly

the

Union

Jack.

Her

best

customers

were

the

United

States,

Germany,

and

France;

and

she

was

pouring

capital

into

Europe

and

America,

where an

extension

of

her

political

dominion

was

absolutely

out

of the

question.

Her

own

colonies,

as

they

matured,

were

raising

tariff

barriers

against

her

wares;

and

she

was

the

only great

trader

in

limitless

regions

of

Africa and

the Far East

that

belonged

to no

western

power,

and

she was

glad

not

to

have these

regions

included in

her

empire.

Apparently something

more

than

mere

capitalism

is

the

explanation

of

why

she

joined

the international

race,

when

it

began,

to

collect new

colonies.

What

drew Britain

into

the

race,

what

kept

her

in

it

and

put

her

in

the

lead,

was the economic

nationalism of

her

rivals.

They

imposed

more

or

less severe restrictions

upon foreign

trade

with

their

possessions,

while she

imposed

none

upon

economic

intercourse

with hers.

Annexa-

tions

by

other

powers

established exclusive

national

control over

terri-

tories

where

traders of all nations had

enjoyed

equal

opportunities

and

where

free

competition

had

given

the lion's

share of

die trade

to the

lion Britain. These other

powers

were

wielding

the sword of

political

sovereignty

to

slice

off her

trade,

on

the

principle

that trade follows

the

flag.

In self-defense

she then

began

to

act on

die

principle

that

the

flag

follows

trade,

proclaiming

her

sovereignty

over lands

that rival

nations

threatened to

appropriate

at her

expense.

Her

object,

like

theirs,

was

trade,

but

with an

important

difference.

Theirs was to shut

doors;

hers

was to

keep

them

open,

primarily

for

herself and

incidentally

for

others.

Hers was to forestall

monopolization by

other

powers,

not

to

gain

a

monopoly

for

herself,

which she

firmly

believed was

contrary

to

sound

policy.

The

soundness

of

her free trade

policy

was more than

economic.

It

was

political

too. Because she

did

not,

like her

rivals,

play

the

dog

in

the

manger,

her annexations

increased

rather

than

diminished facilities

for their

trade.

Therefore each of her

rivals,

on the

whole,

preferred

to

see

her,

rather

than

any

other

power,

take

over a new

territory.

That

was

the

main,

though

not

the

only,

reason

why

she won

more

than

any

other contestant

in

the race.

What

produced

the race

is

not

so

easy

to

explain,

for there

was

a

complexity

of causes.

One

was

the

lifting

of the

veil from

the

dark

continent,

where the

competitive

urge

for

empire

found its chief

outlet.

Though

Europeans

had

been

spreading

round

the

globe

since the

days

of

Columbus,

they

had

neglected

Africa.

Except

at

its

northern and

southern

extremities,

they

had

found

little

to

attract and

much

to

repel

them. It

was a

land of

tropical

jungles

and

burning

deserts,

of

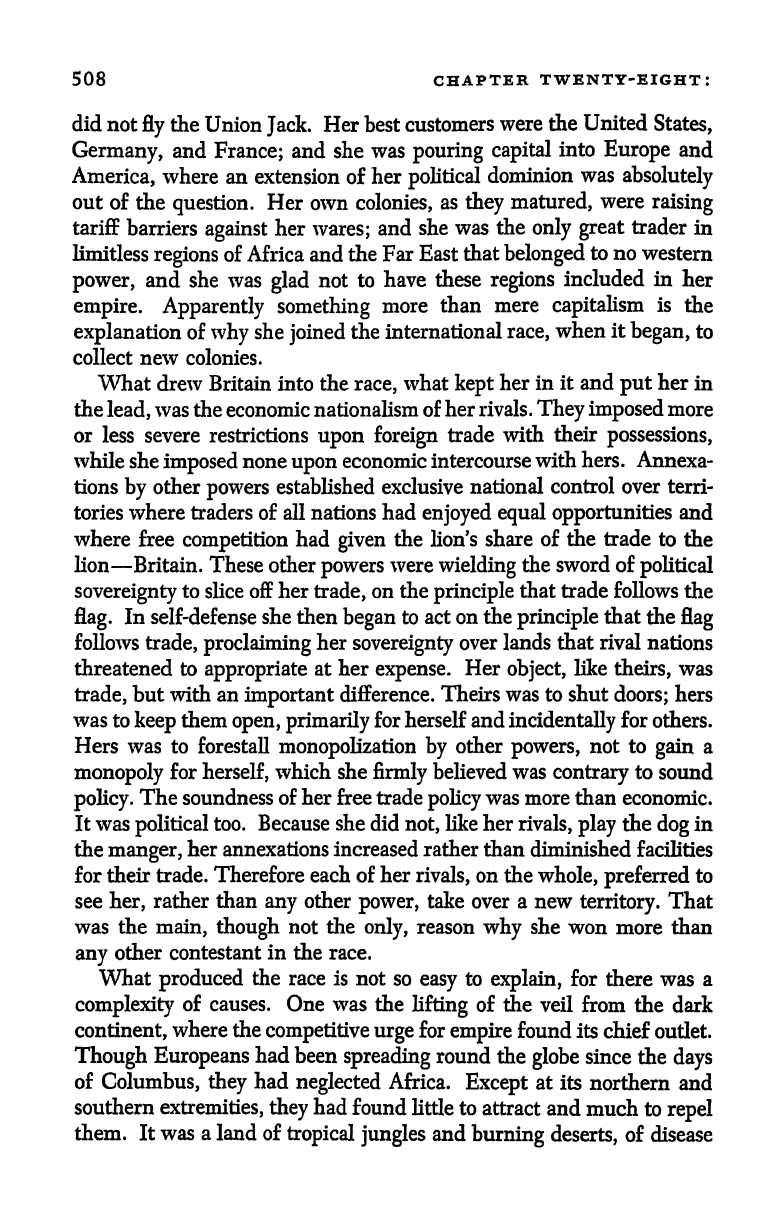

disease

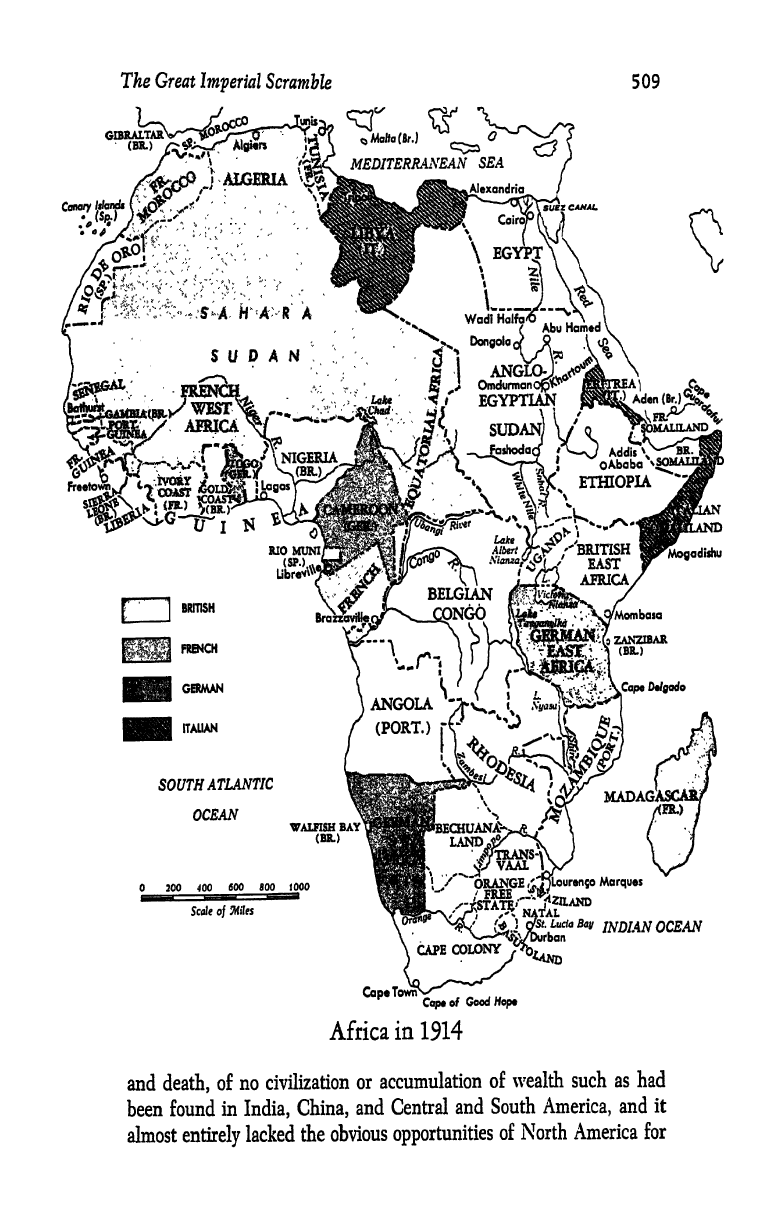

The

Great

Imperial

Scramble

509

GIBRALTAR

(BR.)

200 400

600

SOO 1000

I

I

Scale

of

ftita

irenfo

Marques

INDIAN

OCEAN

Africa

in

1914

and

death,

of

no

civilization

or

accumulation

of

wealth such

as had

been

found

in

India,

China,

and

Central

and

South

America,

and

it

almost

entirely

lacked

the

obvious

opportunities

of

North

America

for

510

CHAPTER

TWENTY-EIGHT:

white

settlers.

Ships

could

not

sail

up

its

rivers,

for

their

navigation

was

blocked

by

bars across their

mouths

or

by

cataracts

not far

above.

Not

until

the middle of the

nineteenth

century

did

white

men

pene-

trate

its vast interior. The

great

pioneer

was

David

Livingstone,

the

Scot

who went to South

Africa

as

a medical

missionary

and in a

few

years

became

an

explorer

whose

name

and fame

flew round

the

world.

Such

was

the

widespread

interest

in his work

that

when he was

thought

to

be

lost

the New York

Herald sent

Henry

M.

Stanley

to

find him.

Many

months

later,

in

1871,

the

young

traveler

encountered

the

veteran

by

Lake

Tanganyika

and

greeted

him

with "Dr.

Livingstone,

I

presume?"

This

was the

introduction

of the man

who

soon

proved

to

be the most successful

of

all the

explorers

of central

Africa.

Stanley's

expedition through

the

Congo

region

from 1874 to

1877,

under

the

joint auspices

of the

proprietors

of

the New York

Herald

and the

London

Daily

Telegraph, accomplished

more

than

any

other

single

exploring

expedition

in

the continent.

By

the

beginning

of the

last

quarter

of

the

century

the

interior of Africa was at last

becoming pretty

well known

to the western

world,

and

enough

of the

potential

wealth

of the

continent was revealed

to

make it

attractive

to

Europeans.

By

this

time, also,

science was

making

Africa

less

forbidding

to

white

men.

They

could now live there more

safely,

thanks

to

new

medical

knowledge;

and

the

progress

of

engineering pointed

the

way

for

them

to

exploit

the

natural

resources of the

interior

with

the

aid of

native

labor.

Moreover,

as

already

suggested,

the

growth

of

industrial

society

on the continent of

Europe,

which

had

lagged

far

behind that

of

Britain,

was

finally

approaching

the

stage

where it felt an

urgent

need

for

new

markets

and

new

sources

of

raw

materials.

Furthermore,

according

to western

standards,

Africa was

a

political

vacuum.

But

even when we have

taken

into

account all the

above

conditions,

we

have

yet

to

explain

why

European powers

rushed

in

to fill the

vacuum.

The

impelling

force was

of the same

nature

as the

vacuum.

It

was

political.

It

was

nationalism,

not

just

economic

nationalism.

Europe

was tense

with

it,

and

Britain

unconsciously

encouraged

it.

She

was

the

only

world

power,

and

continental

nations

envied her

proud posi-

tion.

They

generally

attributed it to her

industrial

supremacy

and

her

imperial possessions.

Her

example

therefore

stimulated

them

to de-

velop

their

own

industries

as

rapidly

as

possible

by

means

of

protective

tariffs,

which

only

intensified

their

national

rivalries,

and to

acquire

colonies,

in

which

pursuit

their

own

economic

nationalism

spurred

them

along.

As the

nations

on

the

continent

adopted

protection

to

The

Great

Imperial

Scramble

511

shield

themselves

against

foreign,

chiefly

British,

industrial

competi-

tion

at

home,

so

also

did

they proclaim

their

sovereignty,

as

far

as

possible,

over

the

markets

and

raw

materials that

they

coveted

abroad.

It

was

to

benefit their

working

classes

no

less

than their

capitalists.

On

the

continent,

as

in

Britain,

the

outburst

of

imperialism

was

an

expres-

sion

of

the

national

will,

a

reflection

of

the democratic

franchise,

the

popular

press,

and

universal

education,

all

of which

were

then

becom-

ing

common.

The

national

will

for

national

aggrandisement

was concerned

with

more

than

economic

gains.

The

Franco-Prussian

War

had

smashed

France,

and her

declining

birth

rate

precluded

any

hope

of

ever

being

able

to face

Germany

again

except

by

supplementing

her

own

man-

power

with

what she

might

train and

arm

in

Africa.

It

was

principally

for

this

purpose

that

she

there added

colony

after

colony

to

the

one,

Algeria,

that

she

had

held for half

a

century.

Bismarck

actually pushed

France

into

her

first

new

imperialist

venture

the seizure

of Tunis

in 1881

to

strengthen Germany's position

in

Europe

by

sowing

the

seed

of discord

between

France and

Italy

and

by diverting

France

from

her

dream of revanche.

Nationalism,

now turned

militant,

had

built

up

such

conflicting

pressures

within the

narrow

confines of

Europe

that

the

only

seeming

alternative

to

explosion

was

expansion.

Nationalism,

by

the internal

law

of

its

development,

was

being glorified

into

imperialism.

Russia

and

Austria were

so situated

that their

imperialist

urge

was directed

toward

contiguous

territories;

whereas

other

European

nations,

being

mutually

hemmed

in,

looked

across

the

sea for the

peaceful

satisfaction

of

their

aggressive

impulse.

Colonies

gave

prestige,

and

prestige

is

a

most

precious

thing

to

a

nation. In the

outburst

of

imperial grabbing

of

territory

in

Africa,

Asia,

and

the

Pacific,

the national

ego

of

each

competing

power

inflated

itself.

Curiously

enough,

it

was

the ruler

of a small

power

who

started

the

scramble,

Leopold

II

of

Belgium.

But

if he had

not done

it,

some

other

power

would

almost

certainly

have done

it not

long

afterward.

Before

Leopold

succeeded

to his father's

throne

in

1865,

he

traveled much

in

distant

lands,

visiting

India,

China,

and

various

parts

of North

Africa;

he

became

inspired

with a

mission

to lead

the

people

of

Belgium

to

enlarge

their

horizon

by

looking

beyond

the sea.

After he

became

king,

the

progress

of

discovery

in

Africa focused

his attention

on

that

part

of the

world.

His

shrewd

mind

saw

great

possibilities

in

harnessing

the

missionary

and

commercial

instincts

for

the

development

of

the dark

512

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT:

continent.

On his

invitation an

unofficial

international

conference

met

in

Brussels

in

1876.

The

upshot

was the

founding

of the

Congo

Free

State,

nominally

under an

international association

but

really

under

the

private

control of

Leopold,

who

provided

most

of

the

capital

and

employed

Stanley

to

direct

the

enterprise

on the

spot.

As

this

Anglo-American

explorer

proceeded

to

build

stations and to

contract

treaties

with

the

natives,

an

agent

of

the

French

government

was

exploring

in

the

northern

Congo

and

he

promptly proclaimed

French

sovereignty

there;

at the

same

time

Portugal

claimed that

the

whole

Congo

was

hers

by

right

of

the

discoveries

her

navigators

had

made

centuries

before.

Leopold

was

embarrassed,

for

it was not as

king

of

Belgium

but as a

private

individual who

headed

a

private

corporation

that he

had

launched his venture.

Therefore he

pulled diplomatic

wires

to

get

international

recognition

of his

International

Association

as

a

sovereign

state.

The

United States was

the

first

power

to

oblige,

by

a

convention of

1884,

and the others

soon

followed suit.

European

intervention in

Egypt

also

began

in

1876,

but it was

in

no

way

connected

with

Leopold's

Congo project

or

tainted with

imperi-

alism.

The

spendthrift

Khedive

Ismail

defaulted in the

payment

of

interest to

the

foreign

bondholders,

and

a

settlement

was

negotiated.

The

Caisse de la

Dette,

a

board

of

trustees

representing

all

the

great

powers,

was

established,

and to it

the

khedive

assigned

specific

reve-

nues

calculated

to

service the

debt.

To

make

sure

that

these

revenues

would

continue

to

flow,

it

was

also

necessary

to

provide

for a

more

efficient

financial

administration in

Egypt;

and as

most

of

the

debt

was

held in

Britain

and

France,

Ismail

agreed

to

the

appointment

of

two

controllers

general,

one

British

and one

French.

Unfortunately

for

all

concerned,

he

intrigued

against

this

Franco-British

Dual

Control.

Then

the

European

powers,

on

the

initiative

of

Germany,

stepped

in

again;

and in

1879

they

got

the

sultan

of

Turkey,

who

was

the

suzerain

of

Egypt,

to

depose

the

uncooperative

khedive

in

favor

of

his

young

son,

Tewfik.

He

was

honest

but

impotent;

and

the

new

regime

was

soon

broken

by

a

revolutionary

movement

headed

by

Arabi

Pasha,

a

fanatical

army

colonel

of

fellah

origin.

This

movement,

which

seems

to

have

been

provoked

by

the

mon-

strous

misgovernment

under

which

the

country

had

long

suffered,

was

nationalist in

character.

It was

directed

primarily

against

the

Turkish

ruling

class

and

secondarily

against

Europeans.

In

1882

there

were

mutinies in

the

Egyptian

army,

whose

soldiers

had

commonly

been

defrauded of

their

pay;

antiforeign

rioting

broke

out,

killing

many

The

Great

Imperial

Scramble 513

Europeans, chiefly

Italians

and

Greeks;

and the

helpless

khedive

turned

over

the

government

to

the

revolutionaries,

who

had

not

the

slightest

capacity

for

directing

it.

Egypt

was

dissolving

into

anarchy,

and the

Dual Control

was

at

an

end.

The

powers

discussed

armed intervention

to

restore

order

and to

protect

the Suez

Canal,

and a

combined

British

and

French

fleet

ap-

peared

off

Alexandria.

Gladstone's

government,

pledged

against

im-

perial

ventures,

shied

away

from an

early

French

suggestion

to use

force;

but

when

conditions in

Egypt

grew

worse,

France turned

shy

and

Britain

bolder.

London

favored Turkish

action

to

quell

the

revolt,

but

Paris

would not

allow

it.

The

sultan

offered

to

give

Egypt

to

Britain,

but

the

prime

minister

and

his

foreign secretary

rejected

it

offhand,

without

even

consulting

the

cabinet.

Finally,

after

both

France

and

Italy

refused a

British

invitation

to

join

in

military

intervention,

the

government

in

London

made

up

its

mind

to

jump

in

alone.

A few

British

regiments

quickly

overthrew Arabi on

the

battlefield

of

Tel-el-

Kebir

and

restored Tewfik to

his

throne

in

the

autumn

of

1882.

Thenceforth

he

was khedive

by

the

grace

of

British

bayonets.

Thus

began

the

British

occupation

of

Egypt,

which

still

legally

belonged

to

the

Turkish

empire

and owed

tribute

to

the sultan.

Glad-

stone

and

his

colleagues

had

not

the

slightest

intention of

annexing

the

country,

or of

declaring

a

protectorate

over

it. Neither could

they

contemplate

immediate

withdrawal,

for

that

would

mean

letting

Egypt

relapse

into

anarchy,

with

grave peril

to

the

Suez Canal.

Yet

they

wanted

to

get

Britain out of

Egypt

as

soon as

possible,

because her

presence

there would

antagonize

other

powers,

particularly

France,

and

restrict

British

freedom

of action elsewhere.

Therefore

they

de-

cided

that

Britain should

clean

up

the mess as

quickly

as

she

could,

and

London

announced

to the world

that the

occupation

was

only

temporary.

The task

proved

to

be

much

bigger

than

expected,

and

the

occupation

much

longer.

One

of the

first

things

that Britain had

to do was

to extricate

Egypt

from

an

impossible

situation in

the

Sudan,

and

it was

a

painful experi-

ence.

Back

in 1820

Egypt

had

undertaken

the

conquest

of that

country.

It was

nearly

completed

under the

grandiose

Ismail,

and

its

enormous

expense

completed

his

financial ruin.

Success, however,

seemed

in

sight

when

he

employed

two able

English

adventurers to

command his

armies

and to

organize

the administration

in

the

Sudan

:

first,

Sir

Samuel

Baker,

the

explorer

of

the sources

of the

Nile;

and

then

General

Charles

Gordon,

famous

as "Chinese

Gordon" because he had

514

CHAPTER

TWENTY-EIGHT:

led a

Chinese

army

to

brilliant

victory

over the formidable

Taiping

rebels

a

few

years

before.

When

this

quixotic

saint and hero

resigned

his

appointment

in

1879,

he

was succeeded

by

a wretched

Egyptian

whom

he

had

dismissed

from the

service,

and

the Sudan

became

a

huge

den

of

iniquity.

There,

paralleling

the

rise of Arabi in

Egypt,

a

religious

fanatic

who

claimed descent from Mahomet

proclaimed

himself

the

Mahdi,

or

Moslem

Messiah,

and

led

a wild

revolt

that

soon

subjected

most

of the

country

to his

own vile

tyranny.

At

the

very

outset

the

British

government

disclaimed

any

responsi-

bility

for

what

Egypt

did in

the

Sudan,

and the

khedive sent

an

army

of

10,000

men

under a

British officer to

subdue the

Mahdi.

It

was

defeated

and

massacred

in

1883.

Tewfik

and his

prime

minister

were

about

to

try

again,

when

the

British

consul

general

in

Cairo

vetoed

the

project

and

London

backed the

veto.

Too

much

Egyptian

revenue

had

been

poured

down

the

Sudanese

drain.

Even

in

ordinary

times

it

amounted

to

200,000

a

year.

This

had to be

stopped

if

Egypt

was

ever

to

pay

its

own

way.

Britain

decided that

Egypt

must

abandon

the

Sudan,

and

straight-

way

assumed

the

responsibility

for

liquidating

the

burdensome

legacy

by

extricating

the

Egyptian

military

and

civilian

personnel

from

the

clutches

of

the

Mahdi.

The

government

called

in

Gordon

and

asked

him

if

he

would do

it.

He

said

yes,

and

that

night

he

left

London

for

Cairo,

where,

at

his

own

request,

he

was

again

commissioned

governor

general

of

the

Sudan,

Rushing

across

the

desert,

he

reached

Khartoum

in

February

1884.

The

inhabitants

welcomed

him

with

open

arms,

believing

he

had

come

to

save

the

country

from

the

rebels.

Their

faith

and the

Egyptian

commission

may

have

infected

him.

Though

he

at

once

began

sending

out

the

women

and

children,

he

displayed

little

eagerness

to

get

the

soldiers

out

until it

was

too late.

A

month

after

his

arrival

he

found

himself

besieged

by

a

gathering

host.

Then

the

prob-

lem

was

how

to

rescue

him

and

his

garrison.

Cairo

and

London

wasted

precious

time

over

whether

the

relieving expedition

should

march

straight

across the

desert

or

follow

the

longer

but

easier

route

up

the

Nile.

The

choice

of

the

latter

entailed

boat

building

and

further

delay.

The

head of

the

advancing

column

approached

Khartoum

at

the

end

of

January

1885,

and saw

nothing

but ruins.

Only

two

days

before,

the

savages

had

broken

in

and

slaughtered

Gordon

and

his

garrison.

The

tragic

death

of

the

hero

who

had

captured

the

imagination

of

the

British

people

nearly

killed

the

Gladstone

ministry.

Fighting

for

its

life

against

a

blaze

of

public

anger,

the

government

refrained

from